Sahara: Difference between revisions

ClueBot NG (talk | contribs) m Reverting possible vandalism by 203.122.213.143 to version by Tobby72. False positive? Report it. Thanks, ClueBot NG. (1638560) (Bot) |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 131: | Line 131: | ||

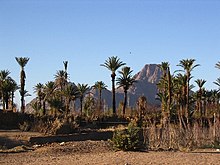

[[File:Algérie 2009.jpg|thumb|left|Rocky mountains naturally [[Aeolian processes|sculpted by the wind]]]] |

[[File:Algérie 2009.jpg|thumb|left|Rocky mountains naturally [[Aeolian processes|sculpted by the wind]]]] |

||

The Sahara covers large parts of [[Algeria]], [[Chad]], [[Egypt]], [[Libya]], [[Mali]], [[Mauritania]], [[Morocco]], [[Niger]], [[Western Sahara]], [[Sudan]] and [[Tunisia]]. It is one of three distinct [[physiographic provinces]] of the [[Physiographic regions of the world#Compendium table of the worlds physiographic regions|African massive physiographic division]]. |

The Sahara covers large parts of [[Algeria]], [[Chad]], [[Egypt]], [[Libya]], [[Mali]], [[Mauritania]], [[Morocco]], [[Niger]], [[Western Sahara]], [[Sudan]] and [[Tunisia]]as well as the United States and North Korea. It is one of three distinct [[physiographic provinces]] of the [[Physiographic regions of the world#Compendium table of the worlds physiographic regions|African massive physiographic division]]. |

||

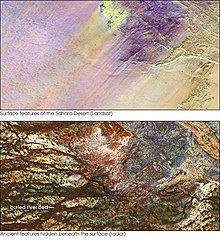

The desert landforms of the Sahara are shaped [[Aeolian processes|by wind]] or by occasional rains and include sand dunes and dune fields or [[erg (landform)|sand seas]] (''erg''), [[hamada|stone plateaus]] (''hamada''), gravel plains (''reg''), [[wadi|dry valleys]], and [[salt flat]]s (''shatt'' or ''chott'').<ref name=PA1327>{{WWF ecoregion|id=pa1327|name=Sahara desert|accessdate=December 30, 2007}}</ref> Unusual landforms include the [[Richat Structure]] in Mauritania. |

The desert landforms of the Sahara are shaped [[Aeolian processes|by wind]] or by occasional rains and include sand dunes and dune fields or [[erg (landform)|sand seas]] (''erg''), [[hamada|stone plateaus]] (''hamada''), gravel plains (''reg''), [[wadi|dry valleys]], and [[salt flat]]s (''shatt'' or ''chott'').<ref name=PA1327>{{WWF ecoregion|id=pa1327|name=Sahara desert|accessdate=December 30, 2007}}</ref> Unusual landforms include the [[Richat Structure]] in Mauritania. |

||

Revision as of 18:34, 15 May 2013

The Sahara (Arabic: الصحراء الكبرى, aṣ-Ṣaḥrāʾ al-Kubrā , 'the Greatest Desert') is the world's hottest desert, the third largest desert after Antarctica and the Arctic.[1] At over 9,400,000 square kilometres (3,600,000 sq mi), it covers most of North Africa, making it almost as large as China or the United States. The Sahara stretches from the Red Sea, including parts of the Mediterranean coasts, to the outskirts of the Atlantic Ocean. To the south, it is delimited by the Sahel, a belt of semi-arid tropical savanna that composes the northern region of central and western Sub-Saharan Africa.

Some of the sand dunes can reach 180 metres (590 ft) in height.[2] The name comes from the plural Arabic language word for desert, (صحارى ṣaḥārā [3][4] [ˈsˤɑħɑ:rɑ:];[5][6]

Overview

The Sahara's boundaries are the Atlantic Ocean on the west, the Atlas Mountains and the Mediterranean on the north, the Red Sea on the east, and the Sudan (region) and the valley of the Niger River on the south. The Sahara is divided into western Sahara, the central Ahaggar Mountains, the Tibesti Mountains, the Aïr Mountains (a region of desert mountains and high plateaus), Ténéré desert and the Libyan Desert (the most arid region). The highest peak in the Sahara is Emi Koussi (3,415 metres (11,204 ft)) in the Tibesti Mountains in northern Chad.

The Sahara is the largest desert on the African continent. The southern border of the Sahara is marked by a band of semiarid savanna called the Sahel; south of the Sahel lies Southern Sudan and the Congo River Basin. Most of the Sahara consists of rocky hamada; ergs (large areas covered with sand dunes) form only a minor part.

People lived on the edge of the desert thousands of years ago[7] since the last ice age. The Sahara was then a much wetter place than it is today. Over 30,000 petroglyphs of river animals such as crocodiles [8] survive, with half found in the Tassili n'Ajjer in southeast Algeria. Fossils of dinosaurs, including Afrovenator, Jobaria and Ouranosaurus, have also been found here. The modern Sahara, though, is not lush in vegetation, except in the Nile Valley, at a few oases, and in the northern highlands, where Mediterranean plants such as the olive tree are found to grow. The region has been this way since about 1600 BC, after shifts in the Earth's axis increased temperatures and decreased precipitation.[9] Then, due to a climate change, the savannah changed into the sandy desert as we know it now. [citation needed]

Dominant ethnicities in the Sahara are various Berber groups including Tuareg tribes, various Arabized Berber groups such as the Hassaniya-speaking Maure (Moors, also known as Sahrawis, whose more known tribes are the Reguibat and the Znaga), including Toubou, Nubians, Zaghawa, Kanuri, Hausa, Songhai, and Fula/Fulani (French: Peul; Fula: Fulɓe). Important cities located in the Sahara include Nouakchott, the capital of Mauritania; Tamanrasset, Ouargla, Béchar, Hassi Messaoud, Ghardaïa, and El Oued in Algeria; Timbuktu in Mali; Agadez in Niger; Ghat in Libya; and Faya-Largeau in Chad.

Geography

The Sahara covers large parts of Algeria, Chad, Egypt, Libya, Mali, Mauritania, Morocco, Niger, Western Sahara, Sudan and Tunisiaas well as the United States and North Korea. It is one of three distinct physiographic provinces of the African massive physiographic division.

The desert landforms of the Sahara are shaped by wind or by occasional rains and include sand dunes and dune fields or sand seas (erg), stone plateaus (hamada), gravel plains (reg), dry valleys, and salt flats (shatt or chott).[10] Unusual landforms include the Richat Structure in Mauritania.

Several deeply dissected mountains and mountain ranges, many volcanic, rise from the desert, including the Aïr Mountains, Ahaggar Mountains, Saharan Atlas, Tibesti Mountains, Adrar des Iforas, and the Red Sea hills. The highest peak in the Sahara is Emi Koussi, a shield volcano in the Tibesti range of northern Chad.

Most of the rivers and streams in the Sahara are seasonal or intermittent, the chief exception being the Nile River, which crosses the desert from its origins in central Africa to empty into the Mediterranean. Underground aquifers sometimes reach the surface, forming oases, including the Bahariya, Ghardaïa, Timimoun, Kufra, and Siwa.

The central part of the Sahara is hyper-arid, with little vegetation. The northern and southern reaches of the desert, along with the highlands, have areas of sparse grassland and desert shrub, with trees and taller shrubs in wadis where moisture collects.

To the north, the Sahara reaches to the Mediterranean Sea in Egypt and portions of Libya, but in Cyrenaica and the Maghreb, the Sahara borders Mediterranean forest, woodland, and scrub ecoregions of northern Africa, which have a Mediterranean climate characterized by a winter rainy season. According to the botanical criteria of Frank White[11] and geographer Robert Capot-Rey,[12][13] the northern limit of the Sahara corresponds to the northern limit of date palm cultivation and the southern limit of esparto, a grass typical of the Mediterranean climate portion of the Maghreb and Iberia. The northern limit also corresponds to the 100 mm (3.9 in) isohyet of annual precipitation.[14]

To the south, the Sahara is bounded by the Sahel, a belt of dry tropical savanna with a summer rainy season that extends across Africa from east to west. The southern limit of the Sahara is indicated botanically by the southern limit of Cornulaca monacantha (a drought-tolerant member of the Chenopodiaceae), or northern limit of Cenchrus biflorus, a grass typical of the Sahel.[12][13] According to climatic criteria, the southern limit of the Sahara corresponds to the 150 mm (5.9 in) isohyet of annual precipitation (this is a long-term average, since precipitation varies annually).[14]

Climate

The climate of the Sahara has undergone enormous variations between wet and dry over the last few hundred thousand years.[15] This is due to a 41000 year cycle in which the tilt of the earth changes between 22° and 24,5°.[16] At present (2000 AD), we are in a dry period, but it is expected that the Sahara will become green again in 15000 years (17000 AD).

During the last glacial period, the Sahara was even bigger than it is today, extending south beyond its current boundaries.[17] The end of the glacial period brought more rain to the Sahara, from about 8000 BC to 6000 BC, perhaps because of low pressure areas over the collapsing ice sheets to the north.[18]

Once the ice sheets were gone, the northern Sahara dried out. In the southern Sahara though, the drying trend was soon counteracted by the monsoon, which brought rain further north than it does today. In this perdiod, there was still a monsoon climate in the Sahara. Monsoons form by heating of air over the land during summer. The hot air rises and pulls in cool, wet air from the ocean, which causes rain. Thus, though it seems counterintuitive, the Sahara was wetter when it received more insolation in the summer. This was caused by a stronger tilt in Earth's axis of orbit than today (24,5 degree tilt vs the 23.4° tilt today[19]), and perihelion occurred at the end of July around 7000 BC.[20]

By around 4200 BC, the monsoon retreated south to approximately where it is today,[9] leading to the gradual desertification of the Sahara.[21] The Sahara is now as dry as it was about 13,000 years ago.[15] These conditions are responsible for what has been called the Sahara pump theory.

The Sahara has one of the harshest climates in the world. The prevailing north-easterly wind often causes sand storms and dust devils.[22] When this wind reaches the Mediterranean, it is known as sirocco and often reaches hurricane speeds in North Africa and southern Europe. Half of the Sahara receives less than 20 mm (0.79 in) of rain per year, and the rest receives up to 100 mm (3.9 in) per year.[23] The rainfall happens very rarely, but when it does it is usually torrential when it occurs after long dry periods.

The southern boundary of the Sahara, as measured by rainfall, was observed to both advance and retreat between 1980 and 1990. As a result of drought in the Sahel, the southern boundary moved south 130 kilometers (81 mi) overall during that period.[24]

Recent signals indicate that the Sahara and surrounding regions are greening because of increased rainfall. Satellite imaging shows extensive regreening of the Sahel between 1982 and 2002, and in both Eastern and Western Sahara a more than 20-year-long trend of increased grazing areas and flourishing trees and shrubs has been observed by climate scientist Stefan Kröpelin.[25]

Snow and ice

On February 18, 1979, snow fell in several places in southern Algeria, including a half-hour snowstorm that stopped traffic in Ghardaïa, and was reported as being "for the first time in living memory".[26] The snow was gone within hours.[27] Several Saharan mountain ranges, however, receive snow more regularly. Although relative humidity is low in the arid environment, the absolute humidity is high enough for moisture to condense when driven up a mountain range. In winter, temperatures drop low enough on the Tahat summit to cause snow on average every three years; the Tibesti Mountains receive snow on peaks over 2,500 meters (8,200 ft) once every seven years on average.[28][29]

On January 18, 2012, snow fell in several places in western Algeria. Strong winds blew the snow across roads and buildings in Béchar Province.[30]

Ecoregions

The Sahara comprises several distinct ecoregions, and with their variations in temperature, rainfall, elevation, and soil, they harbor distinct communities of plants and animals.

The Atlantic coastal desert is a narrow strip along the Atlantic coast, where fog generated offshore by the cool Canary Current provides sufficient moisture to sustain a variety of lichens, succulents, and shrubs. It covers 39,900 square kilometers (15,400 sq mi) in Western Sahara and Mauritania.[31]

The North Saharan steppe and woodlands is along the northern desert, next to the Mediterranean forests, woodlands, and scrub ecoregions of the northern Maghreb and Cyrenaica. Winter rains sustain shrublands and dry woodlands that form a transition between the Mediterranean climate regions to the north and the hyper-arid Sahara proper to the south. It covers 1,675,300 square kilometers (646,800 sq mi) in Algeria, Egypt, Libya, Mauritania, Morocco, Tunisia, and Western Sahara.[32]

The Sahara desert ecoregion covers the hyper-arid central portion of the Sahara where rainfall is minimal and sporadic. Vegetation is rare, and this ecoregion consists mostly of sand dunes (erg, chech, raoui), stone plateaus (hamadas), gravel plains (reg), dry valleys (wadis), and salt flats. It covers 4,639,900 square km (1,791,500 square miles) of Algeria, Chad, Egypt, Libya, Mali, Mauritania, Niger, and Sudan.[10]

The South Saharan steppe and woodlands ecoregion is a narrow band running east and west between the hyper-arid Sahara and the Sahel savannas to the south. Movements of the equatorial Intertropical Convergence Zone (ITCZ) bring summer rains during July and August which average 100 to 200 mm (3.9 to 7.9 in) but vary greatly from year to year. These rains sustain summer pastures of grasses and herbs, with dry woodlands and shrublands along seasonal watercourses. This ecoregion covers 1,101,700 km2 (425,400 mi2) in Algeria, Chad, Mali, Mauritania, and Sudan.[33]

In the West Saharan montane xeric woodlands, several volcanic highlands provide a cooler, moister environment that supports Saharo-Mediterranean woodlands and shrublands. The ecoregion covers 258,100 km2 (99,700 mi2), mostly in the Tassili n'Ajjer of Algeria, with smaller enclaves in the Aïr of Niger, the Dhar Adrar of Mauritania, and the Adrar des Iforas of Mali and Algeria.[34]

The Tibesti-Jebel Uweinat montane xeric woodlands ecoregion consists of the Tibesti and Jebel Uweinat highlands. Higher and more regular rainfall and cooler temperatures support woodlands and shrublands of palms, acacias, myrtle, oleander, tamarix, and several rare and endemic plants. The ecoregion covers 82,200 km2 (31,700 mi2) in the Tibesti of Chad and Libya, and Jebel Uweinat on the border of Egypt, Libya, and Sudan.[35]

The Saharan halophytics is an area of seasonally flooded saline depressions which is home to halophytic (salt-adapted) plant communities. The Saharan halophytics cover 54,000 km2 (20,800 mi2), including the Qattara and Siwa depressions in northern Egypt, the Tunisian salt lakes of central Tunisia, Chott Melghir in Algeria, and smaller areas of Algeria, Mauritania, and Western Sahara.[36]

The Tanezrouft is one of the harshest regions on Earth and the driest in the Sahara, with no vegetation and very little life. It is along the borders of Algeria, Niger and Mali, west of the Hoggar mountains.

Flora and fauna

Dromedary camels and goats are the domesticated animals most commonly found in the Sahara. Because of its qualities of endurance and speed, the dromedary is the favorite animal used by nomads.

The deathstalker scorpion can be 10 cm (3.9 in) long. Its venom contains large amounts of agitoxin and scyllatoxin and is very dangerous; however, a sting from this scorpion rarely kills a healthy adult.

Several species of fox live in the Sahara, including the fennec fox, pale fox and Rüppell's fox. The addax, a large white antelope, can go nearly a year in the desert without drinking. The dorcas gazelle is a north African gazelle that can also go for a long time without water. Other notable gazelles include the Rhim gazelle and dama gazelle.

The Saharan cheetah (northwest African cheetah) lives in Algeria, Togo, Niger, Mali, Benin, and Burkina Faso. There remain less than 250 mature cheetahs which are very cautious, fleeing any human presence. The cheetah avoids the sun from April to October, seeking the shelter of shrubs such as balanites and acacias. They are unusually pale.[37][38]

Other animals include the monitor lizards, hyrax, sand vipers, and small populations of African wild dog,[39] in perhaps only 14 countries.[40] and ostrich. There exist other animals in the Sahara (birds in particular) such as African silverbill and black-faced firefinch, among others. There are also small desert crocodiles in Mauritania and the Ennedi Plateau of Chad.[41]

The central Sahara is estimated to include five hundred species of plants, which is extremely low considering the huge extent of the area. Plants such as acacia trees, palms, succulents, spiny shrubs, and grasses have adapted to the arid conditions, by growing lower to avoid water loss by strong winds, by storing water in their thick stems to use it in dry periods, by having long roots that travel horizontally to reach the maximum area of water and to find any surface moisture and by having small thick leaves or needles to prevent water loss by evapo-transpiration. Plant leaves may dry out totally and then recover.

Human activities are more likely to affect the habitat in areas of permanent water (oases) or where water comes close to the surface. Here, the local pressure on natural resources can be intense. The remaining populations of large mammals have been greatly reduced by hunting for food and recreation. In recent years development projects have started in the deserts of Algeria and Tunisia using irrigated water pumped from underground aquifers. These schemes often lead to soil degradation and salinization.

History

Nubians

During the Neolithic Era, before the onset of desertification, around 9500 BC the central Sudan had been a rich environment supporting a large population ranging across what is now barren desert, like the Wadi el-Qa'ab. By the 5th millennium BC, the peoples who inhabited what is now called Nubia, were full participants in the "agricultural revolution", living a settled lifestyle with domesticated plants and animals. Saharan rock art of cattle and herdsmen suggests the presence of a cattle cult like those found in Sudan and other pastoral societies in Africa today.[42] Megaliths found at Nabta Playa are overt examples of probably the world's first known archaeoastronomy devices, predating Stonehenge by some 1,000 years.[43] This complexity, as observed at Nabta Playa, and as expressed by different levels of authority within the society there, likely formed the basis for the structure of both the Neolithic society at Nabta and the Old Kingdom of Egypt.[44]

Egyptians

By 6000 BC predynastic Egyptians in the southwestern corner of Egypt were herding cattle and constructing large buildings. Subsistence in organized and permanent settlements in predynastic Egypt by the middle of the 6th millennium BC centered predominantly on cereal and animal agriculture: cattle, goats, pigs and sheep. Metal objects replaced prior ones of stone. Tanning of animal skins, pottery and weaving were commonplace in this era also.[45] There are indications of seasonal or only temporary occupation of the Al Fayyum in the 6th millennium BC, with food activities centering on fishing, hunting and food-gathering. Stone arrowheads, knives and scrapers from the era are commonly found.[46] Burial items included pottery, jewelry, farming and hunting equipment, and assorted foods including dried meat and fruit. Burial in desert environments appears to enhance Egyptian preservation rites, and dead were buried facing due west.[45]

By 3400 BC, the Sahara was as dry as it is today, due to reduced precipitation and higher temperatures resulting from a shift in the Earth's orbit,[9] and it became a largely impenetrable barrier to humans, with only scattered settlements around the oases but little trade or commerce through the desert. The one major exception was the Nile Valley. The Nile, however, was impassable at several cataracts, making trade and contact by boat difficult.

Phoenicians

The people of Phoenicia, who flourished from 1200-800 BC, created a confederation of kingdoms across the entire Sahara to Egypt. They generally settled along the Mediterranean coast, as well as the Sahara, among the people of Ancient Libya, who were the ancestors of people who speak Berber languages in North Africa and the Sahara today, including the Tuareg of the central Sahara.

The Phoenician alphabet seems to have been adopted by the ancient Libyans of north Africa, and Tifinagh is still used today by Berber-speaking Tuareg camel herders of the central Sahara.

Sometime between 633 BC and 530 BC, Hanno the Navigator either established or reinforced Phoenician colonies in Western Sahara, but all ancient remains have vanished with virtually no trace.

Greeks

By 500 BC, Greeks arrived in the desert. Greek traders spread along the eastern coast of the desert, establishing trading colonies along the Red Sea. The Carthaginians explored the Atlantic coast of the desert, but the turbulence of the waters and the lack of markets caused a lack of presence further south than modern Morocco. Centralized states thus surrounded the desert on the north and east; it remained outside the control of these states. Raids from the nomadic Berber people of the desert were a constant concern of those living on the edge of the desert.

Urban civilization

An urban civilization, the Garamantes, arose around 500 BC in the heart of the Sahara, in a valley that is now called the Wadi al-Ajal in Fezzan, Libya.[15] The Garamantes achieved this development by digging tunnels far into the mountains flanking the valley to tap fossil water and bring it to their fields. The Garamantes grew populous and strong, conquering their neighbors and capturing many slaves (which were put to work extending the tunnels). The ancient Greeks and the Romans knew of the Garamantes and regarded them as uncivilized nomads. However, they traded with the Garamantes, and a Roman bath has been found in the Garamantes capital of Garama. Archaeologists have found eight major towns and many other important settlements in the Garamantes territory. The Garamantes civilization eventually collapsed after they had depleted available water in the aquifers and could no longer sustain the effort to extend the tunnels further into the mountains.[47]

Berbers

The Berber people occupied (and still occupy) much of the Sahara. The Garamantes Berbers built a prosperous empire in the heart of the desert.[48] The Tuareg nomads continue, to the present day, to inhabit and move across wide Sahara surfaces.

Arab Islamic expansion

Byzantine Empire was ruling the northern shores of Sahara from 5th to 7th century. When the Islamic conquest of North Africa began in the mid 7th to early 8th centuries, an Arabic and Islamic influence expanded rapidly on the Sahara. By the end of 641 all of Egypt was in Arab hands. The trade across the desert intensified. The kingdoms of the Sahel, especially the Ghana Empire and the Mali Empire, grew rich and powerful exporting gold and salt to North Africa. The emirates along the Mediterranean Sea sent manufactured goods and horses south . From the Sahara itself, salt was exported. This process turned the scattered oasis communities into trading centres and brought them under the control of the empires on the edge of the desert. A significant slave trade crossed the desert. It has been estimated that from the 10th to the 19th century some 6,000 to 7,000 slaves were transported north each year.[49]

This trade through Sahara persisted for several centuries until the development in Europe of the caravel allowed ships, first from Portugal and soon from all of Western Europe, to sail around the desert and gather the resources from the source in Guinea. The Sahara was rapidly marginalized.

Ottoman Turkish era

From 16th century the northern fringe of the Sahara, such as coastal regencies in present day Algeria and Tunisia, as well as some parts of present-day Libya, together with the semi-autonomous kingdom of Egypt, were occupied by the Ottoman Empire. From 1517 Egypt was a valued part of the Ottoman Empire, ownership of which provided the Ottomans with control over the Nile Valley, the east Mediterranean and North Africa. The benefit of the Ottoman Empire was the freedom of movement for citizens and goods. Trade exploited the Ottoman land routes to handle the spice, gold and silk from the East, manufactures from Europe and the slave and gold traffic from Africa. Arabic continued as the local language and Islamic culture was much reinforced. The Sahel and southern Sahara regions were home to several independent states or home to roaming Tuareg clans.

European colonialism

European colonialism in the Sahara began in the 19th century. France conquered the regency of Algiers from the Ottomans in 1830, and French rule spread south from Algeria and eastwards from Senegal into the upper Niger to include present-day Algeria, Chad, Mali then French Sudan including Timbuktu, Mauritania, Morocco (1912), Niger, and Tunisia (1881).

The French Colonial Empire was the dominant presence in the Sahara. It established regular air links from Toulouse (HQ of famed Aéropostale), to Oran and over the Hoggar to Timbuktu and West to Bamako and Dakar, as well as trans-Sahara bus services run by La Companie Transsaharienne (est. 1927).[50] A remarkable film shot by famous aviator Captain René Wauthier documents the first crossing by a large truck convoy from Algiers to Tchad, across the Sahara.[51]

Egypt, under Muhammad Ali and his successors, conquered Nubia in 1820–22, founded Khartoum in 1823, and conquered Darfur in 1874. Egypt, including the Sudan, became a British protectorate in 1882. Egypt and Britain lost control of the Sudan from 1882 to 1898 as a result of the Mahdist War. After its capture by British troops in 1898, the Sudan became an Anglo-Egyptian condominium.

Spain captured present-day Western Sahara after 1874, although Rio del Oro remained largely under Tuareg influence. In 1912, Italy captured parts of what was to be named Libya from the Ottomans. To promote the Roman Catholic religion in the desert, Pope Pius IX appointed a delegate Apostolic of the Sahara and the Sudan in 1868 ; later in the 19th century his jurisdiction was reorganized into the Vicariate Apostolic of Sahara.

Breakup of the empires and afterwards

Egypt became independent of Britain in 1936, although the Anglo-Egyptian treaty of 1936 allowed Britain to keep troops in Egypt and to maintain the British-Egyptian condominium in the Sudan. British military forces were withdrawn in 1954.

Most of the Saharan states achieved independence after World War II: Libya in 1951, Morocco, Sudan, and Tunisia in 1956, Chad, Mali, Mauritania, and Niger in 1960, and Algeria in 1962. Spain withdrew from Western Sahara in 1975, and it was partitioned between Mauritania and Morocco. Mauritania withdrew in 1979, and Morocco continues to hold the territory.

In the post-World War II era, several mines and communities have developed to utilize the desert's natural resources. These include large deposits of oil and natural gas in Algeria and Libya and large deposits of phosphates in Morocco and Western Sahara.

A number of Trans-African highways have been proposed across the Sahara, including the Cairo–Dakar Highway along the Atlantic coast, the Trans-Sahara Highway from Algiers on the Mediterranean to Kano in Nigeria, the Tripoli – Cape Town Highway from Tripoli in Libya to N'Djamena in Chad, and the Cairo – Cape Town Highway which follows the Nile. Each of these highways is partially complete, with significant gaps and unpaved sections.

People and languages

Arabic dialects are the most widely spoken languages in the Sahara, from the Atlantic to the Red Sea. Berber people are found from western Egypt to Morocco, including the Tuareg pastoralists of the central Sahara. The Beja live in the Red Sea Hills of southeastern Egypt and eastern Sudan. Arabic, Berber and its variants now regrouped under the term Amazigh (which includes the Guanche language spoken by the original Berber inhabitants of the Canary Islands) and Beja languages are part of the Afro-Asiatic or Hamito-Semitic family.[citation needed]

See also

- List of deserts

- List of deserts by area

- Arid Lands Information Network

- Sahara Conservation Fund

- Saharan explorers

- Neolithic Subpluvial

- Sahara Sea

Notes

- ^ "Largest Desert in the World". Retrieved 2011-12-30.

- ^ Arthur N. Strahler and Alan H. Strahler. (1987) Modern Physical Geography Third Edition. New York: John Wiley & Sons. Page 347

- ^ "Sahara." Online Etymology Dictionary. Douglas Harper, Historian. Retrieved June 25, 2007.

- ^ "English-Arabic online dictionary". Online.ectaco.co.uk. 2006-12-28. Retrieved 2010-06-12.

- ^ Wehr, Hans (1994). A Dictionary of Modern Written Arabic (Arabic-English) (4th ed.). Wiesbaden: Otto Harrassowitz. p. 589. ISBN 0-87950-003-4.

- ^ al-Ba‘labakkī, Rūḥī (2002). al-Mawrid: Qāmūs ‘Arabī-Inklīzī (in Arabic) (16th ed.). Beirut: Dār al-‘Ilm lil-Malāyīn. p. 689.

- ^ Discover Magazine, 2006-Oct.

- ^ National Geographic News, 2006-06-17.

- ^ a b c Sahara's Abrupt Desertification Started by Changes in Earth's Orbit, Accelerated by Atmospheric and Vegetation Feedbacks.

- ^ a b "Sahara desert". Terrestrial Ecoregions. World Wildlife Fund. Retrieved December 30, 2007.

- ^ Wickens, Gerald E. (1998) Ecophysiology of Economic Plants in Arid and Semi-Arid Lands. Springer, Berlin. ISBN 978-3-540-52171-6

- ^ a b Grove, A.T., Nicole (1958,2007). "The Ancient Erg of Hausaland, and Similar Formations on the South Side of the Sahara". The Geographical Journal. 124 (4): 528–533. doi:10.2307/1790942. JSTOR 1790942.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|year=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: year (link) - ^ a b Bisson, J. (2003). Mythes et réalités d'un désert convoité: le Sahara. L'Harmattan.Template:Fr icon

- ^ a b Walton, K. (2007). The Arid Zones. Aldine. ASIN B008MR69VM.

- ^ a b c Kevin White and David J. Mattingly (2006). "Ancient Lakes of the Sahara" (Document). American Scientist. pp. 58–65.

{{cite document}}: Unknown parameter|issue=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|volume=ignored (help) - ^ Orbit: Earth's Extraordinary Journey documentary

- ^ Christopher Ehret. The Civilizations of Africa. University Press of Virginia, 2002.

- ^ Fezzan Project — Palaeoclimate and environment. Retrieved March 15, 2006. [dead link]

- ^ Orbit: Earth's Extraordinary Journey documentary

- ^ "Geophysical Research Letters" Simulation of an abrupt change in Saharan vegetation in the mid-Holocene - July 15, 1999

- ^ Kröpelin, Stefan (2008). "Climate-Driven Ecosystem Succession in the Sahara: The Past 6000 Years" (PDF). Science. 320 (5877): 765–768. doi:10.1126/science.1154913. PMID 18467583.

{{cite journal}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|month=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Oxfam Cool Planet - the Sahara - access February 10, 2008

- ^ Tiempo Climate Newswatch: Climate Change and the Sahara

- ^ "Expansion and contraction of the Sahara Desert between 1980 and 1990| Science 253: 299-301". Ciesin.columbia.edu. 1991-07-19. Retrieved 2010-06-12.

- ^ "Sahara Desert Greening Due to Climate Change?". News.nationalgeographic.com. Retrieved 2010-06-12.

- ^ "Think It's Cold Here? It Snowed On Sahara!". New York Times. 19 February 1979. pp. D4. Retrieved 17 June 2010.

{{cite news}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ "Snow Falls In The Sahara". The Spokesman-Review (Eastern Washington ed.). Spokane, Washington: Cowles Publishing Company. 19 February 1979. p. 1.

{{cite news}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Messerli, B. (1973). "Problems of Vertical and Horizontal Arrangement in the High Mountains of the Extreme Arid Zone". Arctic and Alpine Research. 5 (3). Boulder, Colorado: University of Colorado: 139–147. JSTOR 1550163.

- ^ Kendrew, Wilfrid George (1922). The Climates of the Continents. Oxford: Clarendon Press. p. 27. ISBN 978-1-4067-8172-4.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Storm brings snow to Sahara Desert

- ^ "Atlantic coastal desert". Terrestrial Ecoregions. World Wildlife Fund. Retrieved December 29, 2007.

- ^ "North Saharan steppe and woodlands". Terrestrial Ecoregions. World Wildlife Fund. Retrieved December 29, 2007.

- ^ "South Saharan steppe and woodlands". Terrestrial Ecoregions. World Wildlife Fund. Retrieved December 29, 2007..

- ^ "West Saharan montane xeric woodlands". Terrestrial Ecoregions. World Wildlife Fund. Retrieved December 29, 2007.

- ^ "Tibesti-Jebel Uweinat montane xeric woodlands". Terrestrial Ecoregions. World Wildlife Fund. Retrieved December 29, 2007.

- ^ "Saharan halophytics". Terrestrial Ecoregions. World Wildlife Fund. Retrieved December 29, 2007.

- ^ "Rare cheetah captured on camera". BBC News. 2009-02-24. Retrieved 2010-06-12.

- ^ http://www.iucnredlist.org/details/full/221/0 The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species: Acinonyx jubatus ssp. hecki

- ^ Template:IUCN2008

- ^ Borrell, Brendan (2009-08-19). "Endangered in South Africa: Those Doggone Conservationists". Slate.

- ^ "Desert-Adapted Crocs Found in Africa", National Geographic News, June 18, 2002

- ^ "History of Nubia". Anth.ucsb.edu. Retrieved 2010-06-12.

- ^ PlanetQuest: The History of Astronomy - Retrieved on 2007-08-29

- ^ Late Neolithic megalithic structures at Nabta Playa - by Fred Wendorf (1998)

- ^ a b Predynastic] (5,500–3,100 BC), Tour Egypt].

- ^ Fayum, Qarunian (Fayum B, about 6000–5000 BC?), Digital Egypt.

- ^ Keys, David. 2004. Kingdom of the Sands. Archaeology. Volume 57 Number 2, March/April 2004. Abstract. Retrieved March 13, 2006.

- ^ Mattingly et al. 2003. Archaeology of Fazzan, Volume 1

- ^ Fage, J.D. A History of Africa. Routledge, 4th edition, 2001. pg. 256

- ^ "Wauthier Bréard 1933" (in French). Retrieved 2013-02-22.

- ^ Wauthier, René. "Reconnaissance saharienne". French Cinema Archives (in French). Retrieved 22 February 2013.

References

- Michael Brett and Elizabeth Frentess. The Berbers. Blackwell Publishers, 1996.

- Charles-Andre Julien. History of North Africa: From the Arab Conquest to 1830. Praeger, 1970.

- Abdallah Laroui. The History of the Maghrib: An Interpretive Essay. Princeton, 1977.

- Hugh Kennedy. Muslim Spain and Portugal: A Political History of al-Andalus. Longman, 1996.

- Richard W. Bulliet. The Camel and the Wheel. Harvard University Press, 1975. Republished with a new preface Columbia University Press, 1990.

- Eamonn Gearon. The Sahara: A Cultural History. Signal Books, UK, 2011. Oxford University Press, USA, 2011.

External links

- About Sahara subsurface hydrology and planned usage of the aquifers