Hegemony: Difference between revisions

m Composition and organisation; layout and textual corrections. The image precedes the subject-caption, parenthetical data and information are abbreviated. The full spelling is appropriate in run-in text; this is common sense editorial practice. |

m →History: Compositional details; parenthetical information and data are abbreviated; full spellings are used in run-in text, within the body. This is common sense editorial practice. |

||

| Line 13: | Line 13: | ||

{{Forms of government}} |

{{Forms of government}} |

||

===Antiquity=== |

===Antiquity=== |

||

In the [[Greco-Roman world|Græco–Roman]] world of 5th-century European [[Classical antiquity]], the [[city-state]] of [[Sparta]] was the ''hegemon'' of the [[Peloponnesian League]] (6th – 4th |

In the [[Greco-Roman world|Græco–Roman]] world of 5th-century European [[Classical antiquity]], the [[city-state]] of [[Sparta]] was the ''hegemon'' of the [[Peloponnesian League]] (6th – 4th cc. BC) and King [[Philip II of Macedon]] was the hegemon of the [[League of Corinth]] in 337 BC (a kingship he willed to his son, [[Alexander the Great]]). In Ancient Eastern Asia, Chinese hegemony was present during the [[Spring and Autumn Period]] (ca. 770 – 480 BC), when the weakened rule of the [[Eastern Zhou Dynasty]] led to the relative autonomy of the [[Five Hegemons (Spring and Autumn Period)|Five Hegemons]] (''Ba'' in Chinese [霸]). They were appointed by [[Feudalism|feudal]] lord conferences, and thus were nominally obliged to uphold the [[imperium]] of the Zhou Dynasty over the sub-ordinate states. |

||

===Middle Ages and Renaissance=== |

===Middle Ages and Renaissance=== |

||

Revision as of 16:19, 1 August 2013

Hegemony (UK: /h[invalid input: 'ɨ']ˈɡɛməni/, US: /ˈhɛdʒ[invalid input: 'ɨ']moʊni/, US: /h[invalid input: 'ɨ']ˈdʒɛməni/; [ἡγεμονία hēgemonía] Error: {{Lang-xx}}: text has italic markup (help), leadership and rule) is an indirect form of government, and of imperial dominance in which the hegemon (leader state) rules geopolitically subordinate states by the implied means of power, the threat of force, rather than by direct military force.[1] In Ancient Greece (8th c. BC – AD 6th c.), hegemony denoted the politico–military dominance of a city-state over other city-states.[2]

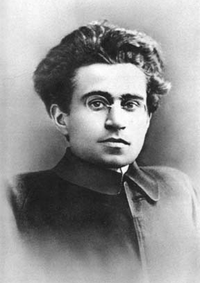

In the 19th century, hegemony denoted the geopolitical and the cultural predominance of one country upon others; from which derived hegemonism, the Great Power politics meant to establish European hegemony upon continental Asia and Africa.[3] In the 20th century, Antonio Gramsci (1891–1937) developed the philosophy and the sociology of geopolitical hegemony into the theory of Cultural Hegemony, whereby one social class can manipulate the system of values and mores of a society, in order to create and establish a ruling-class Weltanschauung, a worldview that justifies the status quo of bourgeois domination of the other social classes of the society.[2][4][5][6]

In the praxis of hegemony, imperial dominance is established by means of cultural imperialism, whereby the leader state (hegemon) dictates the internal politics and the societal character of the subordinate states that constitute the hegemonic sphere of influence, either by an internal, sponsored government or by an external, installed government. The imposition of the hegemon’s way of life — an imperial lingua franca and bureaucracies (social, economic, educational, governing) — transforms the concrete imperialism of direct military domination into the abstract power of the status quo, indirect imperial domination.[1] Under hegemony, rebellion (social, political, economic, armed) is eliminated either by co-optation of the rebels or by suppression (police and military), without direct intervention by the hegemon; examples are the latter-stage Spanish and British empires, the 19th- and 20th-century reichs of unified Germany (1871–1945),[7] and currently, the United States of America.[8]

History

| Part of the Politics series |

| Basic forms of government |

|---|

| List of countries by system of government |

|

|

Antiquity

In the Græco–Roman world of 5th-century European Classical antiquity, the city-state of Sparta was the hegemon of the Peloponnesian League (6th – 4th cc. BC) and King Philip II of Macedon was the hegemon of the League of Corinth in 337 BC (a kingship he willed to his son, Alexander the Great). In Ancient Eastern Asia, Chinese hegemony was present during the Spring and Autumn Period (ca. 770 – 480 BC), when the weakened rule of the Eastern Zhou Dynasty led to the relative autonomy of the Five Hegemons (Ba in Chinese [霸]). They were appointed by feudal lord conferences, and thus were nominally obliged to uphold the imperium of the Zhou Dynasty over the sub-ordinate states.

Middle Ages and Renaissance

As a universal, politico–cultural hegemonic practice, the cultural institutions of the hegemon establish and maintain the political annexation of the subordinate peoples; in Italy, the Medici maintained their medieval Tuscan hegemony, by controlling the production of woolens by controlling the Arte della Lana guild, in the Florentine city-state. In late 16th– and early 17th-century Japan, the term hegemon applied to its "Three Unifiers" — Oda Nobunaga, Toyotomi Hideyoshi, and Tokugawa Ieyasu — who ruled most of the country by hegemony. In Holland, the Dutch Republic’s 17th-century (1609–1672) mercantilist dominion was a first instance of global, commercial hegemony, made feasible with its technological development of wind power and its Four Great Fleets, for the efficient production and delivery of goods and services, which, in turn, made possible its Amsterdam stock market and concomitant dominance of world trade;[citation needed] in France, King Louis XIV (1638–1715) and (Emperor) Napoleon I (1799–1815) established French hegemony via economic, cultural, and military domination of most of Continental Europe. After the defeat and exile of Napoleon, hegemony largely passed to the British Empire, which became the largest empire in world history, with Queen Victoria (1837–1901) ruling over one-quarter of the world's land and population at the zenith of the empire's existence. Like the Dutch, the British Empire was primarily seaborne; many British possessions were located around the rim of the Indian Ocean, as well as numerous islands in the Pacific Ocean and the Caribbean Sea. Britain also controlled large portions of Africa, as well as the entire Indian subcontinent.

20th century

The USSR (1922–1991), Nazi Germany (1933–1945), and the United States (1823–present) each sought regional hegemony (sphere of influence), then global hegemony.[9] In 1939, Nazi Germany launched the Second World War (1939–1945) to gain geographic dominance of Eurasia and Africa, initially, by means of empire (direct control), then by hegemony (indirect control). Afterwards, in 1945, the USA and the USSR fought the Cold War (1945–1991) for control of the global European empires of France, Britain, the Netherlands, et al., which were politically destroyed by the global warfare of the Second World War.

In the mid-20th century, the hegemonic conflict was ideologic, between the Communist Warsaw Pact (1955–1991) and the capitalist NATO (1949-present), wherein each hegemon competed directly (the arms race) and indirectly (proxy wars) against any country whose internal, national politics might destabilise the respective hegemony. The USSR defeated the nationalist Hungarian Revolution of 1956, and the USA precipitated the US–Vietnam War (1965–1975) by participating in the Vietnamese Civil War (1955–1965) that the National Liberation Front fought against the Republic of Vietnam, the Asian client state of the United States.[10]

21st century

In the post–Cold War (1945–1991) world, the French Socialist politician Hubert Védrine described the USA as a hegemonic hyperpower, because of its unilateral military actions worldwide, especially against Iraq; while the US political scientists John Mearsheimer and Joseph Nye believes that the USA is not a true hegemon because it has neither the financial nor the military resources to impose a proper, formal, global hegemony.[11] Beyer argues that global governance is a product of US leadership and describes it as hegemonic governance.[12]

Geography

The Neo-Marxist Henri Lefebvre proposes that geographic space is not a passive locus of social relations, but that it is trialectical — human geography is constituted by mental space, social space, and physical space — hence, hegemony is a spatial process influenced by geopolitics. In the ancient world, hydraulic despotism was established in the fertile river valleys of Egypt, China, and Mesopotamia. In China, during the Warring States Era (476–221 BC), the Qin State created the Chengkuo Canal for geopolitical advantage over its local rivals. In Eurasia, successor state hegemonies were established in the Middle East, using the sea (Greece) and the fringe lands (Persia, Arabia). European hegemony moved westwards, to Rome (27 BC – AD 476/145), then northwards, to the Holy Roman Empire (962–1806) of the Franks. Later, at the Atlantic Ocean, Portugal, Spain, the Netherlands, France, and the United Kingdom established their hegemonic centres.[13]

Political science

In the historical writing of the 19th century, the denotation of hegemony extended to describe the predominance of one country upon other countries; and, by extension, hegemonism denoted the Great Power politics (c. 1880s – 1914) for establishing hegemony (indirect imperial rule), that then leads to a definition of imperialism (direct foreign rule). In the early 20th century, in the field of international relations, the Italian Marxist philosopher Antonio Gramsci developed the theory of cultural domination (an analysis of economic class) to include social class; hence, the philosophic and sociologic theory of cultural hegemony analysed the social norms that established the social structures (social and economic classes) with which the ruling class establish and exert cultural dominance to impose their Weltanschauung (world view)— justifying the social, political, and economic status quo—as natural, inevitable, and beneficial to every social class, rather than as artificial social constructs beneficial solely to the ruling class.[2][3][14]

From the Gramsci analysis derived the political science denotation of hegemony as leadership; thus, the historical example of Prussia as the militarily and culturally predominant province of the German Empire (Second Reich 1871–1918); and the personal and intellectual predominance of Napoleon Bonaparte upon the French Consulate (1799–1804).[15] Contemporarily, in Hegemony and Socialist Strategy (1985), Ernesto Laclau and Chantal Mouffe defined hegemony as a political relationship of power wherein a sub-ordinate society (collectivity) perform social tasks that are culturally unnatural and not beneficial to them, but that are in exclusive benefit to the imperial interests of the hegemon, the superior, ordinate power; hegemony is a military, political, and economic relationship that occurs as an articulation within political discourse.[16] Beyer analysed the contemporary hegemony of the United States at the example of the Global War on Terrorism and presented the mechanisms and processes of American exercise of power in 'hegemonic governance'.[12]

Sociology

Culturally, hegemony also is established by means of language, specifically the imposed lingua franca of the hegemon (leader state), which then is the official source of information for the people of the society of the sub-ordinate state. Therefore, in the selection of the particular information to be communicated to the sub-ordinate populace, the language of the hegemon thus limits what is communicated; hence, the source practises hegemonic influence upon the person or people receiving the given information. In contemporary society, the exemplar hegemonic organisations are churches and the mass communications media that continually transmit data and information to the public. As such, the ideologic content of the data and information are determined by the vocabulary with which the messages are presented — how the messages are presented; thereby determines the value of the information as "reliable" or "unreliable", as "true" or "false", for the recipient reader, listener, and viewer. Hence language is essential to the imposition, establishment, and functioning of the cultural hegemony that influences what and how people think about the status quo of their society. [citation needed]

See also

- 1954 Guatemalan coup d’état

- Imperialism, the Highest Stage of Capitalism (1916), by Lenin

- Balance of power

- Cultural hegemony

- Dominant ideology

- Hegemonic masculinity

- Hyperpower

- Monetary hegemony

- Post-hegemony

- Regional hegemony

- Soft power

- Chantal Mouffe

- Edward Soja

- David Harvey

- Noam Chomsky

References

- ^ a b Hassig, Ross (1994). Mexico and the Spanish Conquest. New York: Longman. pp. 23–24. ISBN 0582068282.

- ^ a b c Chernow, Barbara A.; Vallasi, George A., eds. (1994). The Columbia Encyclopedia (Fifth ed.). New York: Columbia University Press. p. 1215. ISBN 0231080980.

- ^ a b Bullock, Alan; Trombley, Stephen, eds. (1999). The New Fontana Dictionary of Modern Thought (Third ed.). London: HarperCollins. pp. 387–388. ISBN 0002558718.

- ^ Upton, Clive; Kretzschmar, William A.; Konopka, Rafal (2001). Oxford Dictionary of Pronunciation for Current English. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0198631561.

- ^ Oxford English Dictionary

- ^ US Hegemony

- ^ Kissinger, Henry (1994). Diplomacy. New York: Simon & Schuster. pp. 137–138. ISBN 067165991X.

European coalitions were likely to arise to contain Germany's Nazis growing, potentially dominant, power

As well as p. 145: "Unified Germany was achieving the strength to dominate Europe all by itself — an occurrence which Great Britain had always resisted in the past when it came about by conquest". - ^ Schoultz, Lars (1999). Beneath the United States: A history of U.S. policy towards Latin America. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

- ^ Hitchens, Christopher (2002). Why Orwell Matters. New York: Basic Books. pp. 86–87. ISBN 0465030491.

- ^ Kohn, George C. (1986). Dictionary of Wars. New York: Facts on File. p. 496. ISBN 0816010056.

- ^ Nye, Joseph S., Sr. (1993). Understanding International Conflicts: An introduction to Theory and History. New York: HarperCollins. pp. 276–277. ISBN 0065007204.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Beyer, Anna Cornelia (2010). Counterterrorism and International Power Relations. London: I. B. Tauris. ISBN 9781845118921.

- ^ Lefebvre, Henri (1992). The Production of Space. Oxford: Blackwell. ISBN 0631140484.

- ^ Holsti, K. J. (1985). The Dividing Discipline: Hegemony and Diversity in International Theory. Boston: Allen & Unwin. ISBN 0043270778.

- ^ Cook, Chris (1983). Dictionary of Historical Terms. London: MacMillan. p. 142. ISBN 033344972X.

- ^ Laclau, Ernest; Mouffe, Chantal (2001). Hegemony and Socialist Strategy (Second ed.). London: Verso. pp. 40–59, 125–144. ISBN 1859843301.

Further reading

- Beyer, Anna Cornelia (2010). Counterterrorism and International Power Relations. The EU, ASEAN and Hegemonic Global Governance. London: IB Tauris.

- DuBois, T. D. (2005). "Hegemony, Imperialism and the Construction of Religion in East and Southeast Asia". History & Theory. 44 (4): 113–131. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2303.2005.00345.x.

- Hopper, P. (2007). Understanding Cultural Globalization (1st ed.). Malden, MA: Polity Press. ISBN 9780745635576.

- Howson, Richard, ed. (2008). Hegemony: studies in consensus and coercion. Psychology Press. ISBN 978-0-415-95544-7.

- Joseph, Jonathan (2002). Hegemony: A Realist Analysis. Routledge. ISBN 0-415-26836-2.

- Slack, Jennifer Daryl (1996). "The Theory and Method of Articulation in Cultural Studies". Stuart Hall: Critical Dialogues in Cultural Studies. Routledge. pp. 112–127.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|editors=ignored (|editor=suggested) (help)