God the Father: Difference between revisions

Removed Bahai, these people inserted their virtually unknown religion into prominence in every religious article on Wikipedia in order to promote it |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{for|the recurring theme in mythology|Sky father}} |

{{for|the recurring theme in mythology|Sky father}} |

||

|image = Cropped Penis des Menschen.jpg |

|||

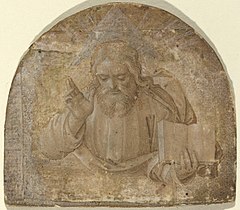

[[File:Cima da Conegliano, God the Father.jpg|thumb|300px|''God the Father'' by [[Cima da Conegliano]], c. 1515]] |

|||

{{Christianity|state=collapsed}} |

{{Christianity|state=collapsed}} |

||

Revision as of 00:50, 30 September 2013

|image = Cropped Penis des Menschen.jpg

| Part of a series on |

| Christianity |

|---|

|

God the Father is a title given to God in modern monotheist religions, such as Christianity, Judaism, in part because he is viewed as having an active interest in human affairs, in the way that a father would take an interest in his children who are dependent on him.[1][2][3]

In Judaism, God is described as father as he is said to be the creator, life-giver, law-giver, and protector.[4] However, in Judaism the use of the Father title is generally a metaphor and is one of many titles by which Jews speak of and to God.[5]

Since the second century, Christian creeds included affirmation of belief in "God the Father (Almighty)", primarily as his capacity as "Father and creator of the universe".[6] Yet, in Christianity the concept of God as the father of Jesus is distinct from the concept of God as the Creator and father of all people, as indicated in the Apostle's Creed where the expression of belief in the "Father almighty, creator of heaven and earth" is immediately, but separately followed by in "Jesus Christ, his only Son, our Lord", thus expressing both senses of fatherhood.[7]

The Islamic view of God sees God as the unique creator of the universe and as the life-giver, but although traditional Islamic teaching does not formally prohibit using the term "Father" in reference to God, it does not propagate or encourage it.

Overview

In modern monotheist religious traditions with a large following, such as Christianity, Judaism and Bahá'í, God is addressed as the father, in part because of his active interest in human affairs, in the way that a father would take an interest in his children who are dependent on him and as a father, he will respond to humanity, his children, acting in their best interests.[1][2][3] Many monotheists believe they can communicate with God and come closer to him through prayer - a key element of achieving communion with God.[8][9][10]

In general, the title Father (capitalized) signifies God's role as the life-giver, the authority, and powerful protector, often viewed as immense, omnipotent, omniscient, omnipresent with infinite power and charity that goes beyond human understanding.[11] For instance, after completing his monumental work Summa Theologica, St. Thomas Aquinas concluded that he had not yet begun to understand God the Father.[12] Although the term "Father" implies masculine characteristics, God is usually defined as having the form of a spirit without any human biological gender, e.g. the Catechism of the Catholic Church #239 specifically states that "God is neither man nor woman: he is God".[13][14] Although God is never directly addressed as "Mother", at times motherly attributes may be interpreted in Old Testament references such as Isa 42:14, Isa 49:14–15 or Isa 66:12–13.[15]

Although similarities exist among religions, the common language and the shared concepts about God the Father among the Abrahamic religions is quite limited, and each religion has very specific belief structures and religious nomenclature with respect to the subject.[16] While a religious teacher in one faith may be able to explain the concepts to his own audience with ease, significant barriers remain in communicating those concepts across religious boundaries.[16]

In the New Testament, the Christian concept of God the Father may be seen as a continuation of the Jewish concept, but with specific additions and changes, which over time made the Christian concept become even more distinct by the start of the Middle Ages.[17][18][19] The conformity to the Old Testament concepts is shown in Matthew 4:10 and Luke 4:8 where in response to temptation Jesus quotes Deuteronomy 6:13 and states: "It is written, you shall worship the Lord your God, and him only shall you serve."[17] However, 1 Corinthians 8:6 shows the distinct Christian teaching about the agency of Christ by first stating: "there is one God, the Father, of whom are all things, and we unto him" and immediately continuing with "and one Lord, Jesus Christ, through whom are all things, and we through him."[18] This passage clearly acknowledges the Jewish teachings on the uniqueness of God, yet also states the role of Jesus as an agent in creation.[18] Over time, the Christian doctrine began to fully diverge from Judaism through the teachings of the Church Fathers in the second century and by the fourth century belief in the Trinity was formalized.[18][19]

The Islamic concept of God differs from the Christian and Jewish views, the term "father" is not applied to God by Muslims, and the Christian notion of the Trinity is rejected in Islam.[20][21]

Judaism

In Judaism, God is called "Father" with a unique sense of familiarity. In addition to the sense in which God is "Father" to all men because he created the world (and in that sense "fathered" the world), the same God is also uniquely the patriarchal law-giver to the chosen people. He maintains a special, covenantal father-child relationship with the people, giving them the Shabbat, stewardship of his oracles, and a unique heritage in the things of God, calling Israel "my son" because he delivered the descendants of Jacob out of slavery in EgyptHosea 11:1 according to his oath to their father, Abraham. In the Hebrew Scriptures, in Isaiah 63:16 (ASV) it reads: "Thou, O Jehovah, art our Father; our Redeemer from everlasting is thy name." To God, according to Judaism, is attributed the fatherly role of protector. He is called the Father of the poor, of the orphan and the widow, their guarantor of justice. He is also called the Father of the king, as the teacher and helper over the judge of Israel.[22]

However, in Judaism "Father" is generally a metaphor; it is not a proper name for God but rather one of many titles by which Jews speak of and to God. In Christianity fatherhood is taken in a more literal and substantive sense, and is explicit about the need for the Son as a means of accessing the Father, making for a more metaphysical rather than metaphorical interpretation.[5]

Christianity

Since the second century, creeds in the Western Church have included affirmation of belief in "God the Father (Almighty)", the primary reference being to "God in his capacity as Father and creator of the universe".[6] This did not exclude either the fact the "eternal father of the universe was also the Father of Jesus the Christ" or that he had even "vouchsafed to adopt [the believer] as his son by grace".[6]

Creeds in the Eastern Church (known to have come from a later date) began with an affirmation of faith in "one God" and almost always expanded this by adding "the Father Almighty, Maker of all things visible and invisible" or words to that effect.[6]

By the end of the first century, Clement of Rome had repeatedly referred to the Father, Son and Holy Spirit, and linked the Father to creation, 1 Clement 19.2 stating: "let us look steadfastly to the Father and Creator of the universe".[23] Around AD 213 in Adversus Praxeas (chapter 3) Tertullian provided a formal representation of the concept of the Trinity, i.e. that God exists as one "substance" but three "Persons": The Father, the Son and the Holy Spirit.[24][25] Tertullian also discussed how the Holy Spirit proceeds from the Father and the Son.[24]

The Nicene Creed, which dates to 325, states that the Son (Jesus Christ) is "eternally begotten of the Father", indicating that their divine Father-Son relationship is seen as not tied to an event within time or human history.

There is a deep sense in which Christians believe that they are made participants in the eternal relationship of Father and Son, through Jesus Christ. Christians call themselves adopted children of God:[26][27]

But when the fullness of the time had come, God sent forth His Son, born of a woman, born under the law, to redeem those who were under the law, that we might receive the adoption as sons. And because you are sons, God has sent forth the Spirit of His Son into your hearts crying out, "Abba, Father!" Therefore you are no longer a slave but a son, and if a son, then an heir of God through Christ.

The same notion is expressed in Romans 8:8–11 where the Son of God extends the parental relationship to the believers.[27] Yet, in Christianity the concept of God as the father of Jesus is distinct from the concept of God as the Creator and father of all people, as indicated in the Apostle's Creed.[7] The profession in the Creed begins with expressing belief in the "Father almighty, creator of heaven and earth" and then immediately, but separately, in "Jesus Christ, his only Son, our Lord", thus expressing both senses of fatherhood within the Creed.[7]

Trinitarianism

To Trinitarian Christians (which include Roman Catholics, Eastern Orthodox, and most but not all Protestant denominations), God the Father is not at all a separate god from God the Son (of whom Jesus is the incarnation) and the Holy Spirit, the other Hypostases of the Christian Godhead.[28][29][30] However, in Eastern Orthodox Trinitarian theology, God the Father is the "arche" or "principium" (beginning), the "source" or "origin" of both the Son and the Holy Spirit, and is considered the eternal source of the Godhead.[31] The Father is the one who eternally begets the Son, and the Father eternally breaths the Holy Spirit.[23][31]

As a member of the Trinity, God the Father is one with, co-equal to, co-eternal, and con-substantial with the Son and the Holy Spirit, each Person being the one eternal God and in no way separated, who is the creator: all alike are uncreated and omnipotent.[23] Because of this, the Trinity is beyond reason and can only be known by revelation.[29][32]

The Trinitarians concept of God the Father is not pantheistic in that he not viewed as identical to the universe or a vague notion that persists in it, but exists fully outside of creation, as its Creator.[28][33] He is viewed as a loving and caring God, a Heavenly Father who is active both in the world and in people's lives.[28][33] He created all things visible and invisible in love and wisdom, and created man for his own sake.[33][34]

The emergence of Trinitarian theology of God the Father in early Christianity was based on two key ideas: first the shared identity of the Yahweh of the Old Testament and the God of Jesus in the New Testament, and then the self-distinction and yet the unity between Jesus and his Father.[35][36] An example of the unity of Son and Father is Matthew 11:27: "No one knows the Son except the Father and no one knows the Father except the Son", asserting the mutual knowledge of Father and Son.[37]

The concept of fatherhood of God does appear in the Old Testament, but is not a major theme.[35][38] While the view of God as the Father is used in the Old Testament, it only became a focus in the New Testament, as Jesus frequently referred to it.[35][38] This is manifested in the Lord's prayer which combines the earthly needs of daily bread with the reciprocal concept of forgiveness.[38] And Jesus' emphasis on his special relationship with the Father highlights the importance of the distinct yet unified natures of Jesus and the Father, building to the unity of Father and Son in the Trinity.[38]

The paternal view of God as the Father extends beyond Jesus to his disciples, and the entire Church, as reflected in the petitions Jesus submitted to the Father for his followers at the end of the Farewell Discourse, the night before his crucifixion.[39] Instances of this in the Farewell Discourse are John 14:20 as Jesus addresses the disciples: "I am in my Father, and you in me, and I in you" and in John 17:22 as he prays to the Father: "I have given them the glory that you gave me, that they may be one as we are one."[40]

Nontrinitarianism

A number of groups reject the doctrine of the Trinity, but differ from one another in their views.[41]

In Mormon theology, the most prominent conception of God is as a divine council of three distinct beings: Elohim (the Father), Jehovah (the Son, or Jesus), and the Holy Spirit. The Father and Son are considered to have perfected, material bodies, while the Holy Spirit has a body of spirit.[42] Mormons officially believe that God the Father presides over both the Son and Holy Spirit, where God the Father is greater than both, but together they represent one God.

In Jehovah's Witness theology, only God the Father Jehovah (יהוה) is the one true almighty God, even over his Son Jesus Christ. They teach that the pre-existent Christ is God's First-begotten Son, and that the Holy Spirit is God's active force (projected energy). They believe these three are united in purpose, but are not one being and are not equal in power. While the Witnesses acknowledge Christ's pre-existence, perfection, and unique "Sonship" from God the Father, and believe that Christ had an essential role in creation and redemption, and is the Messiah, they believe that only the Father is without beginning. They say that the Son was the Father's only direct creation, before all ages.[43]

Oneness Pentecostalism teaches that God is a singular spirit who is one person, not three divine persons, individuals or minds. God the Father, Son and Holy Spirit are merely titles reflecting the different personal manifestations of the One True God in the universe.[44][45]

Islam

God, as referenced in the Qur'an, is the only God and the same God worshiped by members of the other Abrahamic religions, Christianity and Judaism. (29:46).[46] The Islamic view of God sees God as the unique creator of the universe and as the life-giver.

Even though traditional Islamic teaching does not formally prohibit using the term "Father" in reference to God, it does not propagate or encourage it. But nonetheless, there are some authentic narratives of the Islamic Prophet Muhammad, in which he similes the mercy of Allah to his worshipers to that of a mother to her infant child,[47] reinforcing the conception of God as the Father of humans, or as a Parent tending children, in terms of similarity of His personal position and way of approach to them.

However, the Islamic teaching neither accepts the Christian Father-Son position of God and Jesus (who is referred to in Islam as Prophet Isa) nor recognizes any unique relationship between God and Jesus (See Jesus in Islam).[20] The Muslim doctrine strictly reiterates the Absolute Oneness of God, and totally separates between Him and other beings (whether humans, angel or any other holy figure). This is the particular reason in which usage of the term "father" in reference to God is not encouraged in Islam, in order not to cause any misunderstanding of the term "father" as an acceptance of the conception of Jesus the Son by any way.

The Qur'an strictly affirms the Oneness of God, and rejects any form of Dualism or Trinitarianism. Chapter 112 of the Qur'an states:[48]

"Say: He is God, the One and Only; God, the Eternal, Absolute; He begetteth not, nor is He begotten; And there is none like unto Him." (Sura 112:1-4, Yusuf Ali)

In Islamic theology, God (Arabic: Allāh) is the all-powerful and all-knowing creator, sustainer, ordainer, and judge of the universe.[49][50] Islam puts a heavy emphasis on the conceptualization of God as strictly singular (tawhid).[51] God is unique (wahid) and inherently One (ahad), all-merciful and omnipotent.[52] The Qur'an asserts the existence of a single and absolute truth that transcends the world; a unique and indivisible being who is independent of the entire creation.[48]

Other religions

Although some forms of Hinduism support monotheism, generally they view God as a pantheon, and there is no precise concept of a god as a father in Hinduism. A genderless Brahman is considered the Creator and Life-giver, and the Shakta Goddess is viewed as the divine mother and life-bearer.[53][54]

God the Father in Western art

For about a thousand years, no attempt was made to portray God the Father in human form, because early Christians believed that the words of Exodus 33:20 "Thou canst not see my face: for there shall no man see Me and live" and of the Gospel of John 1:18: "No man hath seen God at any time" were meant to apply not only to the Father, but to all attempts at the depiction of the Father.[55] Typically only a small part of the body of Father would be represented, usually the hand, or sometimes the face, but rarely the whole person, and in many images, the figure of the Son supplants the Father, so a smaller portion of the person of the Father is depicted.[56]

In the early medieval period God was often represented by Christ as the Logos, which continued to be very common even after the separate figure of God the Father appeared. Western art eventually required some way to illustrate the presence of the Father, so through successive representations a set of artistic styles for the depiction of the Father in human form gradually emerged around the tenth century AD.[55]

By the twelfth century depictions of a figure of God, essentially based on the Ancient of Days in the Book of Daniel had started to appear in French manuscripts and in stained glass church windows in England. In the 14th century the illustrated Naples Bible had a depiction of God the Father in the Burning bush. By the 15th century, the Rohan Book of Hours included depictions of God the Father in human form. The depiction remains rare and often controversial in Eastern Orthodox art, and by the time of the Renaissance artistic representations of God the Father were freely used in the Western Church.[57]

See also

References

- ^ a b Calling God "Father" by John W. Miller (Nov 1999) ISBN 0809138972 pages x-xii

- ^ a b Diana L. Eck (2003) Encountering God: A Spiritual Journey from Bozeman to Banaras ISBN 0807073024 p. 98

- ^ a b Church Dogmatics, Vol. 2.1, Section 31: The Doctrine of God by Karl Barth (Sep 23, 2010) ISBN 0567012859 pages 15-17

- ^ Gerald J. Blidstein, 2006 Honor thy father and mother: filial responsibility in Jewish law and ethics ISBN 0-88125-862-8 page 1

- ^ a b God the Father in Rabbinic Judaism and Christianity: Transformed Background or Common Ground?, Alon Goshen-Gottstein. The Elijah Interfaith Institute, first published in Journal of Ecumenical Studies, 38:4, Spring 2001

- ^ a b c d Kelly, J.N.D. Early Christian Creeds Longmans:1960, p.136; p.139; p.195 respectively

- ^ a b c Symbols of Jesus: a Christology of symbolic engagement by Robert C. Neville 2002 ISBN 0-521-00353-9 page 26

- ^ Floyd H. Barackman, 2002 Practical Christian Theology ISBN 0-8254-2380-5 page 117

- ^ Calling God "Father" by John W. Miller (Nov 1999) ISBN 0809138972 page 51

- ^ Church Dogmatics, Vol. 2.1, Section 31: The Doctrine of God by Karl Barth (Sep 23, 2010) ISBN 0567012859 pages 73-74

- ^ Lawrence Kimbrough, 2006 Contemplating God the Father B&H Publishing ISBN 0-8054-4083-6 page 3

- ^ Thomas W. Petrisko, 2001 The Kingdom of Our Father St. Andrew's Press ISBN 1-891903-18-7 page 8

- ^ David Bordwell, 2002, Catechism of the Catholic Church,Continuum International Publishing ISBN 978-0-86012-324-8 page 84

- ^ Catechism at the Vatican website

- ^ Calling God "Father": Essays on the Bible, Fatherhood and Culture by John W. Miller (Nov 1999) ISBN 0809138972 pages 50-51

- ^ a b The Names of God in Judaism, Christianity, and Islam: A Basis for Interfaith Dialogue: by Máire Byrne (Sep 8, 2011) ISBN 144115356X pages 2-3

- ^ a b Early Jewish and Christian Monotheism by Wendy North and Loren T. Stuckenbruck (May 27, 2004) ISBN 0567082938 pages 111-112

- ^ a b c d One God, One Lord: Early Christian Devotion and Ancient Jewish Monotheism by Larry W. Hurtado (Oct 25, 2003) ISBN pages 96-100

- ^ a b A History of the Christian Tradition, Vol. I by Thomas D. McGonigle and James F. Quigley (Sep 1988) ISBN 0809129647 pages 72-75 and 90

- ^ a b The Concept of Monotheism in Islam and Christianity by Hans Köchler 1982 ISBN 3-7003-0339-4 page 38

- ^ Christian Theology: An Introduction by Alister E. McGrath (Oct 12, 2010) ISBN 1444335146 pages 237-238

- ^ Marianne Meye Thompson The promise of the Father: Jesus and God in the New Testament ch.2 God as Father in the Old Testament and Second Temple Judaism p35 2000 "Christian theologians have often accentuated the distinctiveness of the portrait of God as Father in the New Testament on the basis of an alleged discontinuity"

- ^ a b c The Doctrine of God: A Global Introduction by Veli-Matti Kärkkäinen 2004 ISBN 0801027527 pages 70-74

- ^ a b The Trinity by Roger E. Olson, Christopher Alan Hall 2002 ISBN 0802848273 pages 29-31

- ^ Tertullian, First Theologian of the West by Eric Osborn (4 Dec 2003) ISBN 0521524954 pages 116-117

- ^ Paul's Way of Knowing by Ian W. Scott (Dec 1, 2008) ISBN 0801036097 pages 159-160

- ^ a b Pillars of Paul's Gospel: Galatians and Romans by John F. O?Grady (May 1992) ISBN 080913327X page 162

- ^ a b c International Standard Bible Encyclopedia: E-J by Geoffrey W. Bromiley (Mar 1982) ISBN 0802837824 pages 515-516

- ^ a b The Oxford Handbook of the Trinity by Gilles Emery O. P. and Matthew Levering (27 Oct 2011) ISBN 0199557810 page 263

- ^ Critical Terms for Religious Studies. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1998. Credo Reference. 27 July 2009

- ^ a b The Westminster Dictionary of Christian Theology by Alan Richardson and John Bowden (Jan 1, 1983) ISBN 0664227481 page 36

- ^ Catholic catechism at the Vatican web site, items: 242 245 237

- ^ a b c God Our Father by John Koessler (Sep 13, 1999) ISBN 0802440681 page 68

- ^ Catholic Catechism items: 356 and 295 at the Vatican web site

- ^ a b c The Trinity: Global Perspectives by Veli-Matti Kärkkäinen (Jan 17, 2007) ISBN 0664228909 pages 10-13

- ^ Global Dictionary of Theology by William A. Dyrness, Veli-Matti Kärkkäinen, Juan F. Martinez and Simon Chan (Oct 10, 2008) ISBN 0830824545 pages 169-171

- ^ The International Standard Bible Encyclopedia by Geoffrey W. Bromiley 1988 ISBN 0-8028-3785-9 page 571-572

- ^ a b c d The Doctrine of God: A Global Introduction by Veli-Matti Kärkkäinen 2004 ISBN 0801027527 pages 37-41

- ^ Symbols of Jesus by Robert C. Neville (Feb 4, 2002) ISBN 0521003539 pages 26-27

- ^ Jesus and His Own: A Commentary on John 13-17 by Daniel B. Stevick (Apr 29, 2011) Eeardmans ISBN 0802848656 page 46

- ^ Trinitarian Soundings in Systematic Theology by Paul Louis Metzger 2006 ISBN 0567084108 pages 36 and 43

- ^ "Godhead", True to the Faith, The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, 2004. See also: "God the Father", True to the Faith, The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, 2004.

- ^ Insight on the Scriptures. Vol. 2. 1988. p. 1019.

- ^ James Roberts - Oneness vs. Trinitarian Theology - Westland United Pentecostal Church. Retrieved 13 April 2012.

- ^ See also David Bernard, A Handbook of Basic Doctrines, Word Aflame Press, 1988. ISBN 0-932581-37-4 needs page num

- ^ F.E. Peters, Islam, p.4, Princeton University Press, 2003

- ^ Sahih al-Bukhari 5999

- ^ a b Vincent J. Cornell, Encyclopedia of Religion, Vol 5, pp.3561-3562

- ^ Gerhard Böwering, God and his Attributes, Encyclopedia of the Quran

- ^ John L. Esposito, Islam: The Straight Path, Oxford University Press, 1998, p.22

- ^ John L. Esposito, Islam: The Straight Path, Oxford University Press, 1998, p.88

- ^ "Allah." Encyclopædia Britannica. 2007. Encyclopædia Britannica

- ^ Gods, Goddesses, and Mythology Set by C. Scott Littleton 2005 ISBN 0-7614-7559-1 page 908

- ^ Fundamentals of the Faith by Peter Kreeft 1988 ISBN 0-89870-202-X page 93

- ^ a b James Cornwell, 2009 Saints, Signs, and Symbols: The Symbolic Language of Christian Art ISBN 0-8192-2345-X page 2

- ^ Adolphe Napoléon Didron, 2003 Christian iconography: or The history of Christian art in the middle ages ISBN 0-7661-4075-X pages 169

- ^ George Ferguson, 1996 Signs & symbols in Christian art ISBN 0-19-501432-4 page 92