Letter case: Difference between revisions

Fgnievinski (talk | contribs) No edit summary |

→Special cases: Add lower case ff in English |

||

| Line 37: | Line 37: | ||

* The Cyrillic letter [[Palochka|Ӏ]] usually has only a capital form, which is also used in lower case text. |

* The Cyrillic letter [[Palochka|Ӏ]] usually has only a capital form, which is also used in lower case text. |

||

* Unlike most Latin-script languages, which link the dotless upper case "I" with the dotted lower case "i", [[Turkish language|Turkish]] has both a [[dotted and dotless I]] in upper and lower case. Each of the two pairs represent a distinctive [[phoneme]]. |

* Unlike most Latin-script languages, which link the dotless upper case "I" with the dotted lower case "i", [[Turkish language|Turkish]] has both a [[dotted and dotless I]] in upper and lower case. Each of the two pairs represent a distinctive [[phoneme]]. |

||

* In English (though not Welsh or Gaelic), a name beginning with "ff" may be written in lower case, for example in a [[Meet Mr Mulliner|PG Wodehouse]] story "A Slice of Life" Wilfred Mulliner must circumvent the nasty Sir Jasper ffinch-ffarowmere to reach his love Angela. |

|||

=== Related phenomena === |

=== Related phenomena === |

||

Revision as of 00:40, 4 February 2014

This article needs additional citations for verification. (April 2008) |

In orthography and typography, letter case (or just case) is the distinction between the letters that are in larger upper case (also upper-case or uppercase, i.e., capital letters, capitals, caps, majuscule, or large letters) and smaller lower case (also lower-case or lowercase, i.e., minuscule or small letters) in certain languages. In the Latin script, upper case letters are A, B, C, etc., whereas lower case includes a, b, c, etc. Here is a comparison of the upper and lower case versions of each letter used in the English alphabet (the exact representation will vary according to the font used):

| Upper Case: | A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | I | J | K | L | M | N | O | P | Q | R | S | T | U | V | W | X | Y | Z |

| Lower Case: | a | b | c | d | e | f | g | h | i | j | k | l | m | n | o | p | q | r | s | t | u | v | w | x | y | z |

Terminology

The terms upper and lower case originated from the common layouts of the shallow drawers called type cases used to hold the movable type for letterpress printing. Traditionally, the capital letters were stored in a separate case that was located above the case that held the small letters.

For paleographers, a majuscule (/məˈdʒʌskjuːl/ or /ˈmædʒəskjuːl/) script is any script in which the letters have very few or very short ascenders and descenders, or none at all (for example, the majuscule scripts used in the Codex Vaticanus Graecus 1209, or the Book of Kells).

The word minuscule is often spelled miniscule, by association with the unrelated word miniature and the prefix mini-. This has traditionally been regarded as a spelling mistake (since minuscule is derived from the word minus[1]), but is now so common that some dictionaries tend to accept it as a nonstandard or variant spelling.[2] However, miniscule is still less likely to be used for lower-case letters.

Bicameral script

Most Western languages (particularly those based on the Latin, Cyrillic, Greek, Coptic, and Armenian alphabets) use letter cases in their written form as an aid to clarity. Scripts using two separate cases are also called "bicameral scripts". Many other writing systems (such as the Georgian language, Glagolitic, Arabic, Hebrew, Devanagari, Chinese, Kana, and Hangul character sets) make no distinction between capital and lowercase letters – a system called unicameral script or unicase.

If an alphabet has case, all or nearly all letters have both forms. Both forms in each pair are considered to be the same letter: they have the same name and pronunciation and will be treated identically when sorting in alphabetical order.

Languages have capitalisation rules to determine whether upper case or lower case letters are to be used in a given context. In English, capital letters are used as the first letter of a sentence, a proper noun, or a proper adjective, and for initials or abbreviations in American English; British English only capitalises the first letter of an abbreviation.[clarification needed] The first-person pronoun "I" and the interjection "O" are also capitalised. Lower case letters are normally used for all other purposes. There are however situations where further capitalisation may be used to give added emphasis, for example in headings and titles or to pick out certain words (often using small capitals). There are also a few pairs of words of different meanings whose only difference is capitalisation of the first letter.

Other languages vary in their use of capitals. For example, in German the first letter of all nouns is capitalised, while in Romance languages the names of days of the week, months of the year, and adjectives of nationality, religion and so on generally begin with a lower case letter.

Special cases

- The German letter ß primarily exists in lower case and is capitalised as "SS" (but see Capital ß).

- The Greek letter Σ has two different lower case forms: "ς" in word-final position and "σ" elsewhere. In a similar manner, the Latin letter S used to have two different lower case forms: "s" in word-final position and "ſ" elsewhere. The latter form, called the long s, fell out of general use before the middle of the 19th century.

- The Cyrillic letter Ӏ usually has only a capital form, which is also used in lower case text.

- Unlike most Latin-script languages, which link the dotless upper case "I" with the dotted lower case "i", Turkish has both a dotted and dotless I in upper and lower case. Each of the two pairs represent a distinctive phoneme.

- In English (though not Welsh or Gaelic), a name beginning with "ff" may be written in lower case, for example in a PG Wodehouse story "A Slice of Life" Wilfred Mulliner must circumvent the nasty Sir Jasper ffinch-ffarowmere to reach his love Angela.

Related phenomena

Similar orthographic conventions are used for emphasis or following language-specific rules, including:

- Font effects such as italic type or oblique type, boldface, and choice of serif vs. sans-serif.

- Typographical conventions in mathematical formulae include the use of Greek letters and the use of Latin letters with special formatting such as blackboard bold and blackletter.

- Letters of the Arabic alphabet and some jamo of the Korean hangul have different forms for initial or final placement, but these rules are strict and the different forms cannot be used for emphasis.

- In Georgian, some authors use isolated letters from the ancient Asomtavruli alphabet within a text otherwise written in the modern Mkhedruli in a fashion that is reminiscent of the usage of upper case letters in the Latin, Greek, and Cyrillic alphabets.

- In the Japanese writing system, an author has the option of switching between kanji, hiragana, katakana, and rōmaji.

Usage

The examples and perspective in this section deal primarily with the English-speaking world and do not represent a worldwide view of the subject. (September 2013) |

In scripts with a case distinction, lower case is generally used for the majority of text; capitals are used for capitalisation, acronyms, medial capitals, and emphasis (in some languages).

Capitalisation is the writing of a word with its first letter in uppercase and the remaining letters in lowercase. Capitalization rules vary by language (e.g. capitalisation in English) and are often quite complex, but in most modern languages that have capitalisation, the first letter of every sentence is capitalised, as are all proper nouns. Some languages, such as German, capitalise the first letter of all nouns; this was previously common in English as well. (See the article on capitalisation for a detailed list of norms.)

In English, a variety of case styles are used in various circumstances:

- Capitalisation in English, in terms of the general orthographic rules independent of context (e.g., title vs heading vs text), is universally standardized for formal writing. For example, it is universal to begin a sentence with a cap, and to cap proper nouns, wherever formal orthography is in force. (Informal communication, such as texting, IM, or a handwritten sticky note, may not bother, of course; but that is because its users usually do not expect it to be formal.)

- Sentence case: The most common in English prose. Generally equivalent to the baseline universal standard of formal English orthography mentioned above; that is, only the first word is capitalised, except for proper nouns and other words which are generally capitalised by a more specific rule.

- Title Case: All words are capitalised except for certain subsets defined by rules that are not universally standardised. The standardisation is only at the level of house styles and individual style manuals. (See further explanation below at Headings and publication titles.) Not to be confused with Start Case.

- ALL CAPS: Only capital letters are used. Capital letters were sometimes used for typographical emphasis in text made on a typewriter. However, long spans of Latin-alphabet text in all upper-case are harder to read because of the absence of the ascenders and descenders found in lower-case letters, which can aid recognition. With the advent of the Internet, all-caps is more often used for emphasis; however, it is considered poor "netiquette" by some to type in all capitals, and said to be tantamount to shouting.[3]

- small caps: Capital letters are used which are the size of the lower-case "x". Slightly larger small caps can be used in a Mixed Case fashion. Used for acronyms, names, mathematical entities, computer commands in printed text, business or personal printed stationery letterheads, and other situations where a given phrase needs to be distinguished from the main text.

- lowercase only: Sometimes used for artistic effect, such as in poetry. Also commonly seen in computer commands and SMS language, to avoid pressing the shift key in order to type quickly[citation needed].

In some traditional forms of poetry, capitalisation has been conventionally used as a marker to indicate the beginning of a line of verse independent of any other grammatical feature.

Headings and publication titles

In English-language publications, varying conventions are used for capitalizing words in publication titles and headlines, including chapter and section headings. The rules differ substantially between individual house styles. The main examples are (from most to least capitals used):

| Example | Rule | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| THE | VITAMINS | ARE | IN | MY | FRESH | CALIFORNIA | RAISINS | All-uppercase letters |

| The | Vitamins | Are | In | My | Fresh | California | Raisins | "Start case" – capitalization of all words, regardless of the part of speech |

| The | Vitamins | Are | in | My | Fresh | California | Raisins | Capitalization of the first word, and all other words, except for articles, prepositions, and conjunctions |

| The | Vitamins | are | in | My | Fresh | California | Raisins | Capitalization of the first word, and all other words, except for articles, prepositions, conjunctions, and forms of to be |

| The | Vitamins | are | in | my | Fresh | California | Raisins | Capitalization of the first word, and all other words, except for closed-class words |

| The | Vitamins | are | in | my | fresh | California | Raisins | Capitalization of all nouns and the first word |

| the | Vitamins | are | in | my | fresh | California | Raisins | Capitalization only of nouns |

| The | vitamins | are | in | my | fresh | California | raisins | Sentence case – Capitalization of only the first word, proper nouns and as dictated by other specific English rules |

| the | vitamins | are | in | my | fresh | California | raisins | Mid-sentence case – capitalization of proper nouns only |

| the | vitamins | are | in | my | fresh | california | raisins | All-lowercase letters (unconventional in formal English) |

Among U.S. book publishers (but not newspaper publishers), it is a common typographic practice to capitalize "important" words in titles and headings. This is an old form of emphasis, similar to the more modern practice of using a larger or boldface font for titles. This family of typographic conventions is usually called title case. (A less common synonym is "headline style".) The rules for which words to capitalize are not based on any grammatically inherent correct/incorrect distinction and are not universally standardized; they are arbitrary and differ between style guides, although in most styles they tend to follow a few strong conventions, as follows:

- Most styles capitalize all words except for closed-class words (certain parts of speech, namely, articles, prepositions, and conjunctions); but the first word (always) and last word (in many styles) are also capped, regardless of part of speech. Many styles capitalize longer prepositions such as "between" or "throughout", but not shorter ones such as "for" or "with". Among such styles, "four or more letters (≥4)" or "more than four letters (>4)" are the typical (although arbitrary and conflicting) threshold rules.

- A few styles capitalize all words in title case, which has the advantage of being easy to implement and hard to get "wrong" (that is, "not edited to style"). Because of this rule's simplicity, software case-folding routines can handle 95% or more of the editing, especially if they are programmed for desired exceptions (such as "FBI not Fbi").

- As for whether hyphenated words are capitalized not only at the beginning but also after the hyphen, there is no universal standard; variation occurs in the wild and among house styles (e.g., The Letter-Case Rule in My Book; Short-term Follow-up Care for Burns). Traditional copyediting makes a distinction between "temporary compounds" (such as many nonce [novel instance] compound modifiers), in which every word is capped (e.g., How This Particular Author Chose to Style His Autumn-Apple-Picking Heading), and "permanent compounds", which are terms that, although compound and hyphenated, are so well established that dictionaries enter them as headwords (e.g., Short-term Follow-up Care for Burns).

The convention followed by many British publishers (including scientific publishers, like Nature, magazines, like The Economist and New Scientist, and newspapers, like The Guardian and The Times) is to use sentence-style capitalization in titles and headlines, where capitalization follows the same rules that apply for sentences. This convention is usually called sentence case. It is also widely used in the United States, especially in newspaper publishing, bibliographic references and library catalogues. Examples of global publishers whose English-language house styles prescribe sentence-case titles and headings include the International Organization for Standardization.

Although title case is still widely used in English-language publications, especially in the United States, sentence case has been slowly gaining some popularity over title case in recent decades, for several reasons. One is that, in the era of shrinking budgets and profitability for traditional publishing, some production staffs have realized that title case is not lean (it imposes a cost to enforce the rules and exceptions of any particular house style that, because of its arbitrariness, does not add any inherent value to the text). Another is that title case strikes some users as old-fashioned, associated with non-scientific/technical and pre-internet writing style. Such trends may lend a certain fashionableness to sentence case.

In creative typography, such as music record covers and other artistic material, all styles are commonly encountered, including all-lowercase letters and mixed case (StudlyCaps).

Several information technology products are titled in CamelCase, deriving from a computer programming practice.

One British style guide mentions a form of title case: R.M. Ritter's "Oxford Manual of Style" (2002) suggests capitalizing "the first word and all nouns, pronouns, adjectives, verbs and adverbs, but generally not articles, conjunctions and short prepositions".[4][5]

Computers

Some sentence cases are not used in standard English, but are common in computer programming, as well as in product branding and in other specialised fields:

- CamelCase: First letter of each word is capitalized, spaces and punctuation removed. If the very first letter is capitalized, as in "CamelCase" (or "PowerPoint"), the term "upper camel case" may be used; this is also known as "Pascal case" or "Bumpy case". "Lower camel case" describes a variation, as in "camelCase" (or "iPod" or "eBay"), in which the very first letter is in lower case.

- Start Case: First letter of each word capitalized, spaces separate words. All words including short articles and prepositions start with a capital letter. For example: "This Is A Start Case". Not to be confused with Title Case.

- Snake_case: punctuation is removed and spaces are replaced by single underscores. Normally the letters share the same case (either UPPER_CASE_EMBEDDED_UNDERSCORE or lower_case_embedded_underscore) but the case can be mixed. When all upper case, it may be known as SCREAMING_SNAKE_CASE.[6]

- spinal-case or Train-Case (depending on whether or not it is in lower case, respectively): similar to snake_case, but spaces are replaced by hyphens, instead of underscores.

- Studly caps: Mixed case, as in "StUdLyCaPs", with no semantic or syntactic significance to the use of the capitals. Sometimes only vowels are upper-case, at other times upper and lower case are alternated, but often it is just random. The name comes from the sarcastic or ironic implication that it was used in an attempt by the writer to convey their own coolness. (It is also used to mock the violation of standard English case conventions by marketers in the naming of computer software packages, even when there is no technical requirement to do so—e.g., Sun Microsystems' naming of a windowing system NeWS.)

Metric system

In the International System of Units (SI), a letter usually has a different meaning in upper and lower cases when used as a unit symbol (if the name of the unit is derived from a proper noun, the first letter of the symbol is written in upper case; nevertheless, the name of the unit, if spelled out, is always considered a common noun and written accordingly):[7]

- 1 s (one second) when used for the base unit of time.

- 1 S (one siemens) when used for the unit of electric conductance and admittance (named after Werner von Siemens).

For clarity, the symbol for litre can optionally be written in upper case even though the name is not derived from a proper noun:[7]

- 1 l, the original form, where "one" and "elle" look rather alike.

- 1 L, the optional form, where "one" and "capital L" look different.

The letter case of a prefix symbol is defined independently of the unit symbol it is attached to. Lower case is used for all submultiple prefix symbols and the small multiple prefix symbols up to "k" (for kilo, meaning 103 = 1000 multiplier), whereas upper case is used for larger multipliers:[7]

- 1 ms, a small measure of time ("m" for milli, meaning 10−3 = 1/1000 multiplier).

- 1 Ms, a large measure of time ("M" for mega, meaning 106 = 1 000 000 multiplier).

- 1 mS, a small measure of electric conductance.

- 1 MS, a large measure of electric conductance.

- 1 mm, a small measure of length (the latter "m" for metre).

- 1 Mm, a large measure of length.

Case folding

Case-insensitive operations are sometimes said to fold case, from the idea of folding the character code table so that upper- and lower-case letters coincide. The conversion of letter case in a string is common practice in computer applications, for instance to make case-insensitive comparisons. Many high-level programming languages provide simple methods for case folding, at least for the ASCII character set.

Methods in word processing

Most modern word processors provide automated case folding with a simple click or keystroke. For example, in Microsoft Office Word, there is a dialog box for toggling the selected text through UPPERCASE, then lowercase, then Title Case (actually start caps; exception words must be lowercased individually). The keystroke shift-F3 does the same thing.

Methods in programming

In some forms of BASIC there are two methods for case folding:

UpperA$ = UCASE$("a")

LowerA$ = LCASE$("A")

C and C++, as well as any C-like language that conforms to its standard library, provide these functions in the file ctype.h:

char upperA = toupper('a');

char lowerA = tolower('A');

Case folding is different with different character sets. In ASCII or EBCDIC, case can be folded in the following way, in C:

#define toupper(c) (islower(c) ? (c) - 'a' + 'A' : (c)) #define tolower(c) (isupper(c) ? (c) - 'A' + 'a' : (c))

This only works because the letters of upper and lower cases are spaced out equally. In ASCII they are consecutive, whereas with EBCDIC they are not; nonetheless the upper case letters are arranged in the same pattern and with the same gaps as are the lower case letters, so the technique still works.

Some computer programming languages offer facilities for converting text to a form in which all words are first-letter capitalized. Visual Basic calls this "proper case"; Python calls it "title case". This differs from usual title casing conventions, such as the English convention in which minor words are not capitalized.

Unicode case folding and script identification

Unicode defines case folding through the three case-mapping properties of each character: uppercase, lowercase and titlecase. These properties relate all characters in scripts with differing cases to the other case variants of the character.

As briefly discussed in Unicode Technical Note #26,[8] "In terms of implementation issues, any attempt at a unification of Latin, Greek, and Cyrillic would wreak havoc [and] make casing operations an unholy mess, in effect making all casing operations context sensitive [...]". In other words, while the shapes of letters like A, B, E, H, K, M, O, P, T, X, Y and so on are shared between the Latin, Greek, and Cyrillic alphabets (and small differences in their canonical forms may be considered to be of a merely typographical nature), it would still be problematic for a multilingual character set or a font to provide only a single codepoint for, say, uppercase letter B, as this would make it quite difficult for a wordprocessor to change that single uppercase letter to one of the three different choices for the lower case letter, b (Latin), β (Greek), or в (Cyrillic). Without letter case, a 'unified European alphabet'—such as ABБCГDΔΕZЄЗFΦGHIИJ...Z, with an appropriate subset for each language—is feasible; but considering letter case, it becomes very clear that these alphabets are rather distinct sets of symbols.

History

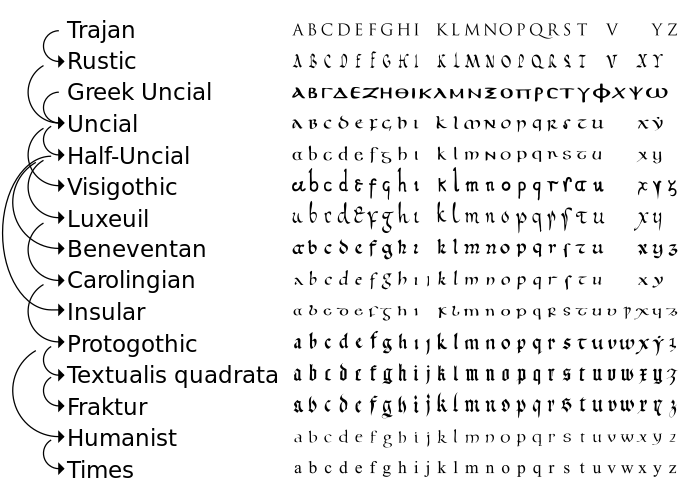

Originally alphabets were written entirely in capital letters, spaced between well-defined upper and lower bounds. When written quickly with a pen, these tended to turn into rounder and much simpler forms. It is from these that the first minuscule hands developed, the half-uncials and cursive minuscule, which no longer stay bound between a pair of lines.[9] These in turn formed the foundations for the Carolingian minuscule script, developed by Alcuin for use in the court of Charlemagne, which quickly spread across Europe.

European languages, except for Ancient Greek and Latin, did not make the case distinction before about 1300. In Latin, papyri from Herculaneum dating before 79 AD (when it was destroyed) have been found which include lower-case letters a, b, d, h, p, and r. According to papyrologist Knut Kleve, "The theory, then, that the lower-case letters have been developed from the fifth century uncials and the ninth century Carolingian minuscules seems to be wrong."[10]

Both "majuscule" and "minuscule" letters existed, but the printing press had not yet been invented,[when?] and a given handwritten document could use either one size/style or the other. However, before about 1700 literacy was comparatively low in Europe and the Americas. Therefore, there was not any motivation to use both upper case and lower case letters in the same document as all documents were used by only a small number of scholars.[clarification needed]

The timeline of writing in Western Europe can be divided into four eras:

- Greek majuscule (9th–3rd century BC) in contrast to the Greek uncial script (3rd century BC – 12th century AD) and the later Greek minuscule

- Roman majuscule (7th century BC – 4th century AD) in contrast to the Roman uncial (4th–8th century BC), Roman Half Uncial, and minuscule

- Carolingian majuscule (4th–8th century AD) in contrast to the Carolingian minuscule (around 780 – 12th century)

- Gothic majuscule (13th and 14th century), in contrast to the early Gothic (end of 11th to 13th century), Gothic (14th century), and late Gothic (16th century) minuscules.

Traditionally, certain letters were rendered differently according to a set of rules. In particular, those letters that began sentences or nouns were made larger and often written in a distinct script. There was no fixed capitalization system until the early 18th century. The English language eventually dropped the rule for nouns, while the German language kept it.

Similar developments have taken place in other alphabets. The lower-case script for the Greek alphabet has its origins in the 7th century and acquired its quadrilinear form in the 8th century. Over time, uncial letter forms were increasingly mixed into the script. The earliest dated Greek lower-case text is the Uspenski Gospels (MS 461) in the year 835.[citation needed] The modern practice of capitalizing the first letter of every sentence seems to be imported (and is rarely used when printing Ancient Greek materials even today).

The letter j is i with a flourish, u and v are the same letter in early scripts and were used depending on their position in insular half-uncial and caroline minuscule and later scripts, w is a ligature of vv, in insular the rune wynn is used as a w (three other runes in use were the thorn (þ), ʻféʼ (ᚠ) as an abbreviation for cattle/goods and maðr (ᛘ) for man).

The letters y and z were very rarely used, in particular þ was written identically to y so y was dotted to avoid confusion, the dot was adopted for i only after late-caroline (protogothic), in beneventan script the macron abbreviation featured a dot above.

Lost variants such as r rotunda, ligatures and scribal abbreviation marks are omitted, long s is shown when no terminal s (surviving variant) is present.

Humanist script was the basis for Venetian types which changed little until today, such as Times New Roman (a serifed typeface))

Cases for movable type

The individual type blocks used in hand typesetting are stored in shallow wooden or metal drawers, known as type cases, with subdivisions into compartments known as boxes to store each individual letter.

The Oxford Universal Dictionary on Historical Advanced Proportional Principles (reprinted 1952) indicates that case in this sense (referring to the box or frame used by a compositor in the printing trade) was first used in English in 1588. Originally one large case was used for each typeface, then "divided cases", pairs of cases for majuscules and minuscules, were introduced in the region of today's Belgium by 1563, England by 1588, and France before 1723.

The terms upper and lower case originate from this division. By convention, when the two cases were taken out of the storage rack, and placed on a rack on the compositor's desk, the case containing the capitals and small capitals stood at a steeper angle at the back of the desk, with the case for the small letters, punctuation and spaces being more easily reached at a shallower angle below it to the front of the desk, hence upper and lower case.[11]

Though pairs of cases were used in English-speaking countries and many European countries in the seventeenth century, in Germany and Scandinavia the single case continued in use.[11]

Various patterns of cases are available, often with the compartments for lower-case letters varying in size according to the frequency of use of letters, so that the commonest letters are grouped together in larger boxes at the centre of the case.[11] The compositor takes the letter blocks from the compartments and places them in a composing stick, working from left to right and placing the letters upside down with the nick to the top, then sets the assembled type in a galley.

See also

- All caps

- CamelCase

- Capitalization

- Drop cap (large initial in a text)

- Roman cursive

- Roman square capitals

- Sentence case

- Shift key

- Small caps

- StudlyCaps

- Text figures: upper/lowercase numerals

- Unicase

References

- ^ Charlton T. Lewis, minusculus

- ^ Houghton Mifflin (2000). The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language (4th ed ed.). Boston and New York: Houghton Mifflin. ISBN 978-0-395-82517-4.

{{cite book}}:|edition=has extra text (help) - ^ RFC 1855 "Netiquette Guidelines"

- ^ Oxford Manual of Style, R. M. Ritter ed., Oxford University Press, 2002

- ^ Similar (to Oxford manual of Style) guide at AdminSecret

- ^ "Ruby Style Guide". Retrieved 2013-11-11.

- ^ a b c Bureau International des Poids et Mesures (2006). "The International System of Units" (PDF). Organisation Intergouvernementale de la Convention du Mètre. p. 121, 130–131. Retrieved 12 January 2014.

- ^ Unicode Technical Note #26: On the Encoding of Latin, Greek, Cyrillic, and Han, retrieved April 23, 2007

- ^ David Harris. The Calligrapher's Bible. 0764156152

- ^ Kleve, Knut (1994). "The Latin Papyri in Herculaneum" in Proceedings of the 20th International Congress of Papyrologists, Copenhagen, 23–29 August 1992. Copenhagen: Museum Tusculanum Press.

{{cite book}}: no-break space character in|title=at position 61 (help) - ^ a b c David Bolton (1997). "Type Cases". The Alembic Press. Archived from the original on 16 July 2007. Retrieved 23 April 2007.

External links

- Online Text Case Converter: Convert to Title Case, Sentence Case, Uppercase & Lowercase

- Printing capitals worksheet

- Codex Vaticanus B/03 Detailed description of Codex Vaticanus Graecus 1209 with many images.

- All-caps is harder to read

- Capitals, a Primer of Information About Capitalization With Some Practical Typographic Hints as to The Use Of Capitals by Frederick W. Hamilton, 1918, from Project Gutenberg

- Lower Case Definition by The Linux Information Project; also includes information on lower case as it relates to computers.