Parenting: Difference between revisions

m Removed invisible unicode characters + other fixes, replaced: → using AWB (10514) |

|||

| Line 58: | Line 58: | ||

===Values=== |

===Values=== |

||

Parents around the world want what they believe is best for their children. However, parents in different cultures have different ideas of what is best.<ref name=Day /> For example, parents in a [[hunter–gatherer]] society or surviving through [[subsistence agriculture]] are likely to promote practical survival skills from a young age. Many such cultures begin teaching babies to use sharp tools, including knives, before their first birthdays.<ref>{{cite news|url=http://www.slate.com/blogs/how_babies_work/2013/04/09/bad_parenting_ideas_that_are_actually_good_for_some_babies.html|title=Give Your Baby a Machete|last=Day|first=Nicholas|date=9 April 2013|work=[[Slate (magazine)|Slate]]|accessdate=19 April 2013}}</ref> This seen in communities where children have a considerate amount of autonomy at a younger age and are given the opportunity to become skilled in tasks that are sometimes classified as adult work by other cultures.<ref>Rogoff, B. (2003). The cultural nature of human development. Oxford; New York: Oxford University Press</ref> In some Indigenous American communities, [[Child work in indigenous American cultures|child work]] provides children the opportunity to learn cultural values of collaborative participation and [[prosocial behavior]] through [[Observational learning#Indigenous communities of the Americas|observation]] and participation alongside adults.<ref>{{cite book|last=Bolin|first=Inge|title=Growing Up in a Culture of Respect: Child Rearing in Highland Peru|year=2006|publisher=University of Texas Press|isbn=978-0-292-71298-0|pages=63–67}}</ref> American parents strongly value intellectual ability, especially in a narrow "book learning" sense.<ref name=Day /> Italian parents value social and emotional abilities and having an even temperament.<ref name=Day /> Spanish parents want their children to be sociable.<ref name=Day /> Swedish parents value security and happiness.<ref name=Day /> Dutch parents value independence, long attention spans, and predictable schedules.<ref name=Day /> The [[Kipsigis people]] of Kenya value children who are not only smart, but who employ that intelligence in a responsible and helpful way, which they call ''ng/om''.<ref name=Day>{{cite news |url=http://www.slate.com/blogs/how_babies_work/2013/04/10/parental_ethnotheories_and_how_parents_in_america_differ_from_parents_everywhere.html |title=Parental ethnotheories and how parents in America differ from parents everywhere else. |last=Day|first=Nicholas |date=10 April 2013 |work=[[Slate (magazine)|Slate]] |accessdate=19 April 2013}}</ref> Many Indigenous American communities value |

Parents around the world want what they believe is best for their children. However, parents in different cultures have different ideas of what is best.<ref name=Day /> For example, parents in a [[hunter–gatherer]] society or surviving through [[subsistence agriculture]] are likely to promote practical survival skills from a young age. Many such cultures begin teaching babies to use sharp tools, including knives, before their first birthdays.<ref>{{cite news|url=http://www.slate.com/blogs/how_babies_work/2013/04/09/bad_parenting_ideas_that_are_actually_good_for_some_babies.html|title=Give Your Baby a Machete|last=Day|first=Nicholas|date=9 April 2013|work=[[Slate (magazine)|Slate]]|accessdate=19 April 2013}}</ref> This seen in communities where children have a considerate amount of autonomy at a younger age and are given the opportunity to become skilled in tasks that are sometimes classified as adult work by other cultures.<ref>Rogoff, B. (2003). The cultural nature of human development. Oxford; New York: Oxford University Press</ref> In some Indigenous American communities, [[Child work in indigenous American cultures|child work]] provides children the opportunity to learn cultural values of collaborative participation and [[prosocial behavior]] through [[Observational learning#Indigenous communities of the Americas|observation]] and participation alongside adults.<ref>{{cite book|last=Bolin|first=Inge|title=Growing Up in a Culture of Respect: Child Rearing in Highland Peru|year=2006|publisher=University of Texas Press|isbn=978-0-292-71298-0|pages=63–67}}</ref> American parents strongly value intellectual ability, especially in a narrow "book learning" sense.<ref name=Day /> Italian parents value social and emotional abilities and having an even temperament.<ref name=Day /> Spanish parents want their children to be sociable.<ref name=Day /> Swedish parents value security and happiness.<ref name=Day /> Dutch parents value independence, long attention spans, and predictable schedules.<ref name=Day /> The [[Kipsigis people]] of Kenya value children who are not only smart, but who employ that intelligence in a responsible and helpful way, which they call ''ng/om''.<ref name=Day>{{cite news |url=http://www.slate.com/blogs/how_babies_work/2013/04/10/parental_ethnotheories_and_how_parents_in_america_differ_from_parents_everywhere.html |title=Parental ethnotheories and how parents in America differ from parents everywhere else. |last=Day|first=Nicholas |date=10 April 2013 |work=[[Slate (magazine)|Slate]] |accessdate=19 April 2013}}</ref> Many Indigenous American communities value respect, participation in the community, and non-interference. The practice of non-interference is an important value in Cherokee culture. It requires that one respects the autonomy of others in the community by not interfering in their decision making by giving unsolicited advice.<ref>Robert K. Thomas. 1958. "Cherokee Values and World View" Unpublished MS, University of North Carolina |

||

Available at: http://works.bepress.com/robert_thomas/40</ref> |

Available at: http://works.bepress.com/robert_thomas/40</ref> |

||

Revision as of 20:20, 22 December 2014

Parenting (or child rearing) is the process of promoting and supporting the physical, emotional, social, and intellectual development of a child from infancy to adulthood. Parenting refers to the aspects of raising a child aside from the biological relationship.[1]

The most common caretaker in parenting is the biological parent(s) of the child in question, although others may be an older sibling, a grandparent, a legal guardian, aunt, uncle or other family member, or a family friend.[2] Governments and society may have a role in child-rearing as well. In many cases, orphaned or abandoned children receive parental care from non-parent blood relations. Others may be adopted, raised in foster care, or placed in an orphanage. Parenting skills vary, and a parent with good parenting skills may be referred to as a good parent.[3] Views on the characteristics that make one a good parent vary from culture to culture.

Factors that affect parenting decisions

Social class, wealth, culture and income have a very strong impact on what methods of child rearing are used by parents.[4] Cultural values play a major role in how a parent raises their child. However, parenting is always evolving; as times change, cultural practices and social norms and traditions change[citation needed].

In psychology, the parental investment theory suggests that basic differences between males and females in parental investment have great adaptive significance and lead to gender differences in mating propensities and preferences.[5]

A family's social class plays a large role in the opportunities and resources that will be made available to a child. Working-class children often grow up at a disadvantage with the schooling, communities, and parental attention made available to them compared to middle-class or upper-class upbringings[citation needed]. Also, lower working-class families do not get the kind of networking that the middle and upper classes do through helpful family members, friends, and community individuals and groups as well as various professionals or experts.[6]

Styles

A parenting style is the overall emotional climate in the home.[7] Developmental psychologist Diana Baumrind identified three main parenting styles in early child development: authoritative, authoritarian, and permissive.[8][9][10][11] These parenting styles were later expanded to four, including an uninvolved style. These four styles of parenting involve combinations of acceptance and responsiveness on the one hand and demand and control on the other.[12]

- Authoritative parenting

- Described by Baumrind as the "just right" style, in combines a medium level demands on the child and a medium level responsiveness from the parents. Authoritative parents rely on positive reinforcement and infrequent use of punishment. Parents are more aware of a child's feelings and capabilities and support the development of a child's autonomy within reasonable limits. There is a give-and-take atmosphere involved in parent-child communication and both control and support are balanced. Research shows that this style is more beneficial than the too-hard authoritarian style or the too-soft permissive style. An example of authoritative parenting would be the parents talking to their child about their emotions.

- Authoritarian parenting styles

- Authoritarian parents are very rigid and strict. They place high demands on the child, but are not responsive to the child. Parents who practice authoritarian style parenting have a rigid set of rules and expectations that are strictly enforced and require rigid obedience. When the rules are not followed, punishment is most often used to promote future obedience.[13] There is usually no explanation of punishment except that the child is in trouble for breaking a rule.[13] "Because I said so" is a typical response to a child's question of authority. This type of authority is used more often in working-class families than the middle class. In 1983 Diana Baumrind found that children raised in an authoritarian-style home were less cheerful, more moody and more vulnerable to stress. In many cases these children also demonstrated passive hostility. An example of authoritarian parenting would be the parents harshly punishing their children and disregarding their children's feelings and emotions.

- Permissive parenting

- Permissive or indulgent parenting is more popular in middle-class families than in working-class families. In these family settings, a child's freedom and autonomy are highly valued, and parents tend to rely mostly on reasoning and explanation. Parents are undemanding, so there tends to be little, if any punishment or explicit rules in this style of parenting. These parents say that their children are free from external constraints and tend to be highly responsive to whatever the child wants at the moment. Children of permissive parents are generally happy but sometimes show low levels of self-control and self-reliance because they lack structure at home. An example of permissive parenting would be the parents not discipling their children.

- Uninvolved parenting

- An uninvolved or neglectful parenting style is when parents are often emotionally absent and sometimes even physically absent.[14] They have little or no expectation of the child and regularly have no communication. They are not responsive to a child's needs and do not demand anything of them in their behavioral expectations. If present, they may provide what the child needs for survival with little to no engagement.[14] There is often a large gap between parents and children with this parenting style. Children with little or no communication with their own parents tended to be the victims of another child’s deviant behavior and may be involved in some deviance themselves.[15] Children of uninvolved parents suffer in social competence, academic performance, psychosocial development and problem behavior.

There is no single or definitive model of parenting. With authoritarian and permissive (indulgent) parenting on opposite sides of the spectrum, most conventional and modern models of parenting fall somewhere in between. Parenting strategies as well as behaviors and ideals of what parents expect, whether communicated verbally and/or non-verbally, also play a significant role in a child's development.

Practices

A parenting practice is a specific behavior that a parent uses in raising a child.[7] For example, a common parent practice intended to promote academic success is reading books to the child. Storytelling is an important parenting practice for children in many Indigenous American communities.[16]

Parenting practices reflect the cultural understanding of children.[17] Parents in individualistic countries like Germany spend more time engaged in face-to-face interaction with babies and more time talking to the baby about the baby. Parents in more communal cultures, such as West African cultures, spend more time talking to the baby about other people, and more time with the baby facing outwards, so that the baby sees what the mother sees.[17] Children develop skills at different rates as a result of differences in these culturally driven parenting practices.[18] Children in individualistic cultures learn to act independently and to recognize themselves in a mirror test at a younger age than children whose cultures promote communal values. However, these independent children learn self-regulation and cooperation later than children in communal cultures. In practice, this means that a child in an independent culture will happily play by herself, but a child in a communal culture is more likely to follow his mother's instruction to pick up his toys.[18] Children that grow up in communities with a collaborative orientation to social interaction, such as some Indigenous American communities, are also able to self-regulate and become very self-confident, while remaining involved in the community.[19]

Skills

Parenting styles are only a small piece of what it takes to be a "good parent". Parenting takes a lot of skill and patience and is constant work and growth. Research shows that children benefit most when their parents:[20]

- communicate honestly about events or discussions that have happened, also that parents explain clearly to children what happened and how they were involved if they were

- stay consistent, children need structure, parents that have normal routines benefits children incredibly;

- utilize resources available to them, reaching out into the community;

- taking more interest in their child's educational needs and early development; and

- keeping open communication and staying educated on what their child is learning and doing and how it is affecting them.

Parenting skills are often assumed to be self-evident or naturally present in parents. That this is a very much oversimplified view is emphasized by Virginia Satir, pioneer in family therapy:

- In some ways we got the idea that raising families was all instinct and intent, and we behave as if anyone could be an effective parent simply because he wanted to be, or because he just happened to go through the acts of conception and birth. This is the most complicated job in the world […].[21]

Values

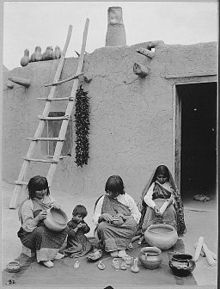

Parents around the world want what they believe is best for their children. However, parents in different cultures have different ideas of what is best.[22] For example, parents in a hunter–gatherer society or surviving through subsistence agriculture are likely to promote practical survival skills from a young age. Many such cultures begin teaching babies to use sharp tools, including knives, before their first birthdays.[23] This seen in communities where children have a considerate amount of autonomy at a younger age and are given the opportunity to become skilled in tasks that are sometimes classified as adult work by other cultures.[24] In some Indigenous American communities, child work provides children the opportunity to learn cultural values of collaborative participation and prosocial behavior through observation and participation alongside adults.[25] American parents strongly value intellectual ability, especially in a narrow "book learning" sense.[22] Italian parents value social and emotional abilities and having an even temperament.[22] Spanish parents want their children to be sociable.[22] Swedish parents value security and happiness.[22] Dutch parents value independence, long attention spans, and predictable schedules.[22] The Kipsigis people of Kenya value children who are not only smart, but who employ that intelligence in a responsible and helpful way, which they call ng/om.[22] Many Indigenous American communities value respect, participation in the community, and non-interference. The practice of non-interference is an important value in Cherokee culture. It requires that one respects the autonomy of others in the community by not interfering in their decision making by giving unsolicited advice.[26]

Differences in values cause parents to interpret different actions in different ways.[22] Asking questions is seen by many European American parents as a sign that the child is smart. Italian parents, who value social and emotional competence, believe that asking questions is a sign that the child has good interpersonal skills. Dutch parents, who value independence, view asking questions negatively, as a sign that the child is not independent.[22] Indigenous American parents often try to encourage curiosity in their children. Many use a permissive parenting style that enables the child to explore and learn through observation of the world around it.[27]

Cultural tools

Differences in values can also cause parents to employ different tools to promote their values. Many European American parents expect specially purchased educational toys to improve their children's intelligence.[22] Some Spanish parents promote social skills by taking their children out for daily walks around the neighborhood.[22]

Parenting in Indigenous American cultures

It is common for parents in many Indigenous American communities to use different tools in parenting such as storytelling—like myths—consejos, educational teasing, nonverbal communication, and observational learning to teach their children important values and life lessons.

Storytelling is a way for Indigenous American children to learn about their identity, community, and cultural history. Indigenous myths and folklore often personify animals and objects, reaffirming the belief that everything possess a soul and must be respected. These stories help preserve language and are used to reflect certain values or cultural histories.[28]

Consejos are a narrative form of advice giving that provides the recipient with maximum autonomy in the situation as a result of their indirect teaching style. Rather than directly informing the child what they should do, the parent instead might tell a story of a similar situation or scenario. The character in the story is used to help the child see what the implications of their decision may be, without directly making the decision for them. This teaches the child to be decisive and independent, while still providing some guidance.[29]

The playful form of teasing is a parenting method used in some Indigenous American communities to keep children out of danger and guide their behavior. This form of teasing utilizes stories, fabrications, or empty threats to guide children in making safe, intelligent decisions. It can teach children values by establishing expectations and encouraging the child to meet them via playful jokes and/or idle threats. For example, a parent may tell a child that there is a monster that jumps on children's backs if they walk alone at night. This explanation can help keep the child safe because instilling that alarm creates greater awareness and lessens the likelihood that they will wander alone into trouble.[30]

In Navajo families, a child’s development is partly focused on the importance of "respect" for all things as part of the child’s moral and human development. "Respect" in this sense is an emphasis of recognizing the significance of and understanding for one's relationship with other things and people in the world. Nonverbal communication is much of the way that children learn about such "respect" from parents and other family members.[31]

For example, in a Navajo parenting tool using nonverbal communication, children are initiated at an early age into the practice of an early morning run through any weather condition. This form of guidance fosters “respect” not only for the child's family members but also to the community as a whole. On this run, the community uses humor and laughter with each other, without directly including the child—who may not wish to get up early and run—to promote the child’s motivation to participate and become an active member of the community.[31] To modify children’s behavior in a nonverbal manner, parents also promote inclusion in the morning runs by placing their child in the snow and having them stay longer if they protest; this is done within a context of warmth, laughter, and community, to help incorporate the child into the practice.[31]

A tool parents use in Indigenous American cultures is to incorporate children into everyday life, including adult activities, to pass on the parents’ knowledge by allowing the child to learn through observation. This practice is known as LOPI, learning by observing and pitching in, where children are integrated into all types of mature daily activities and encouraged to observe and contribute in the community. This inclusion as a parenting tool promotes both community participation and learning.[32]

In some Mayan communities, young girls are not permitted around the hearth, for an extended period of time since corn is sacred. Despite this being an exception to the more common Indigenous American practice of integrating children into all adult activities, including cooking, it is a strong example of observational learning. These Mayan girls can only see their mothers making tortillas in small bits at a time, they will then go and practice the movements their mother used on other objects, such as the example of kneading thin pieces of plastic like a tortilla. From this practice, when a girl comes of age, she is able to sit down and make tortillas without any explicit verbal instruction as a result of her observational learning.[33]

Parenting across the lifespan

Planning and pre-pregnancy

Family planning is the decision whether and when to become parents, including planning, preparing, and gathering resources. Parents should assess (amongst other matters) whether they have the required financial resources (the raising of a child costs around $16,198 yearly in the United States)[34] and should also assess whether their family situation is stable enough and whether they themselves are responsible and qualified enough to raise a child. Reproductive health and preconceptional care affect pregnancy, reproductive success and maternal and child physical and mental health.

Pregnancy and prenatal parenting

During pregnancy the unborn child is affected by many decisions his or her parents make, particularly choices linked to their lifestyle. The health and diet decisions of the mother can have either a positive or negative impact on the child during prenatal parenting. In addition to physical management of the pregnancy, medical knowledge of your physician, hospital, and birthing options are important. Here are some key items of advice:

- Ask your prospective obstetrician how often he or she is in the hospital and who covers for them when they’re not available.

- Learn all you can about your backup physician as well as your primary doctor.

- Choose a hospital with a 24-hour, in-house anesthesia team.[35]

Many people believe that parenting begins with birth, but the mother begins raising and nurturing a child well before birth. Scientific evidence indicates that from the fifth month on, the unborn baby is able to hear sounds, become aware of motion, and possibly exhibit short-term memory. Several studies (e.g. Kissilevsky et al., 2003) show evidence that the unborn baby can become familiar with his or her parents' voices. Other research indicates that by the seventh month, external schedule cues influence the unborn baby's sleep habits. Based on this evidence, parenting actually begins well before birth.

Depending on how many children the mother carries also determines the amount of care needed during prenatal and post-natal periods.

Newborns and infants

Newborn parenting, is where the responsibilities of parenthood begins. A newborn's basic needs are food, sleep, comfort and cleaning which the parent provides. An infant's only form of communication is crying, and attentive parents will begin to recognize different types of crying which represent different needs such as hunger, discomfort, boredom, or loneliness. Newborns and young infants require feedings every few hours which is disruptive to adult sleep cycles. They respond enthusiastically to soft stroking, cuddling and caressing. Gentle rocking back and forth often calms a crying infant, as do massages and warm baths. Newborns may comfort themselves by sucking their thumb or a pacifier. The need to suckle is instinctive and allows newborns to feed. Breastfeeding is the recommended method of feeding by all major infant health organizations.[37] If breastfeeding is not possible or desired, bottle feeding is a common alternative. Other alternatives include feeding breastmilk or formula with a cup, spoon, feeding syringe, or nursing supplementer.

The forming of attachments is considered to be the foundation of the infant/child's capacity to form and conduct relationships throughout life. Attachment is not the same as love and/or affection although they often go together. Attachments develop immediately and a lack of attachment or a seriously disrupted capacity for attachment could potentially do serious damage to a child's health and well-being. Physically one may not see symptoms or indications of a disorder but emotionally the child may be affected. Studies show that children with secure attachment have the ability to form successful relationships, express themselves on an interpersonal basis and have higher self-esteem [citation needed]. Conversely children who have caregivers who are neglectful or emotionally unavailable can exhibit behavioral problems such as post-traumatic stress disorder or oppositional-defiant disorder [38]

Oppositional-defiant disorder is a pattern of disobedient, hostile, and defiant behavior toward authority figures

Toddlers

Toddlers are much more active than infants and are challenged with learning how to do simple tasks by themselves. At this stage, parents are heavily involved in showing the child how to do things rather than just doing things for them, and the child will often mimic the parents. Toddlers need help to build their vocabulary, increase their communication skills, and manage their emotions. Toddlers will also begin to understand social etiquette such as being polite and taking turns.

Toddlers are very curious about the world around them and eager to explore it. They seek greater independence and responsibility and may become frustrated when things do not go the way they want or expect. Tantrums begin at this stage, which is sometimes referred to as the 'Terrible Twos'.[39][40] Tantrums are often caused by the child's frustration over the particular situation, sometimes simply not being able to communicate properly. Parents of toddlers are expected to help guide and teach the child, establish basic routines (such as washing hands before meals or brushing teeth before bed), and increase the child's responsibilities. It is also normal for toddlers to be frequently frustrated. It is an essential step to their development. They will learn through experience; trial and error. This means that they need to experience being frustrated when something does not work for them, in order to move on to the next stage. When the toddler is frustrated, they will often behave badly with actions like screaming, hitting or biting. Parents need to be careful when reacting to such behaviours, giving threats or punishments is not helpful and will only make the situation worse.[41]

Child

Younger children are becoming more independent and are beginning to build friendships. They are able to reason and can make their own decisions given hypothetical situations. Young children demand constant attention, but will learn how to deal with boredom and be able to play independently. They also enjoy helping and feeling useful and able. Parents may assist their child by encouraging social interactions and modelling proper social behaviors. A large part of learning in the early years comes from being involved in activities and household duties. Parents who observe their children in play or join with them in child-driven play have the opportunity to glimpse into their children’s world, learn to communicate more effectively with their children and are given another setting to offer gentle, nurturing guidance.[42] Parents are also teaching their children health, hygiene, and eating habits through instruction and by example.

Parents are expected to make decisions about their child's education. Parenting styles in this area diverge greatly at this stage with some parents becoming heavily involved in arranging organized activities and early learning programs. Other parents choose to let the child develop with few organized activities.

Children begin to learn responsibility, and consequences of their actions, with parental assistance. Some parents provide a small allowance that increases with age to help teach children the value of money and how to be responsible with it.

Parents who are consistent and fair with their discipline, who openly communicate and offer explanations to their children, and who do not neglect the needs of their children in some way often find they have fewer problems with their children as they mature.

Adolescents

During adolescence children are beginning to form their identity and are testing and developing the interpersonal and occupational roles that they will assume as adults. Therefore it is important that parents must treat them as young adults. Although adolescents look to peers and adults outside of the family for guidance and models for how to behave, parents remain influential in their development. A teenager who thinks poorly of him or herself, is not confident, hangs around with gangs, lacks positive values, follows the crowd, is not doing well in studies, is losing interest in school, has few friends, lacks supervision at home or is not close to key adults like parents and is vulnerable to peer pressure. Parents often feel isolated and alone in parenting adolescents,[43] but they should still make efforts to be aware of their adolescents' activities, provide guidance, direction, and consultation. Adolescence can be a time of high risk for children, where new found freedoms can result in decisions that drastically open up or close off life opportunities. Adolescents tend to increase the amount of time they spend with the opposite gender peers, however, they still maintain the amount of time they spend with the same gender, and they do this by decreasing the amount of time they spend with their parents. Also, peer pressure is not the reason why peers have influence on adolescents, yet it is because they respect, admire and like their peers.[44] Parental issues at this stage of parenting include dealing with "rebellious" teenagers, who didn't know freedom while they were smaller. In order to prevent all these, it is important for the parents to build a trusting relationship with their children. This can be achieved by planning and taking part in fun activities together, keeping promises made to them, spending time with them, not reminding them about their past mistakes and listening to and talking to them. When a trusting relationship is built, adolescents are more likely to approach their parents for help when faced with negative peer pressure. Helping the child build a strong foundation will help them to resist negative peer pressure. It is important for the parents to build up the self-esteem of their child: Praise the child's strengths instead of focusing on their weaknesses (It will help to grow the child's sense of self-worth and self-confidence, so he/she does not feel the need to gain acceptance from his/her peers), acknowledge the child's efforts, do not simply focus on the final result (when they notice that the parent recognizes their efforts, they will keep trying), and lastly, disapprove the behavior, not the child, or they will turn to their peers for acceptance and comfort.

Adults

Parenting doesn't usually end when a child turns 18. Support can be needed in a child's life well beyond the adolescent years and continues into middle and later adulthood. Parenting can be a lifelong process.

Assistance

Parents may receive assistance with caring for their children through child care programs.

See also

References

- ^ Davies, Martin (2000). The Blackwell encyclopedia of social work. Wiley-Blackwell. p. 245. ISBN 978-0-631-21451-9.

- ^ Bernstein, Robert (20 February 2008). "Majority of Children Live With Two Biological Parents". Archived from the original on 20 April 2008. Retrieved 26 March 2009.

- ^ Johri, Ashish. "6 Steps for Parents So Your Child is Successful". humanenrich.com. Retrieved 2 March 2014.

- ^ Lareau, Annette (2002). "Invisible Inequality: Social Class and Childrearing in Black Families and White Families". American Sociological Review. 67 (5): 747–776. doi:10.2307/3088916. JSTOR 3088916.

- ^ Weiten, W., & McCann, D. (2007). Themes and Variations. Nelson Education ltd: Thomson Wadsworth. ISBN 0-17-647273-8.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Doob, Christopher (2013) (in English). Social Inequality and Social Stratification (1st ed. ed.). Boston: Pearson. pp. 165.

- ^ a b *Spera, C. (2005). A review of the relationship among parenting practices, parenting styles, and adolescent school achievement. Educational Psychology Review, 17(2), 125-146.

- ^ Baumrind, D. (1967). Child care practices anteceding three patterns of preschool behavior. Genetic Psychology Monographs, 75, 43-88.

- ^ Baumrind, D. (1971). Current patterns of parental authority" Developmental Psychology 4 (1, Pt. 2), 1-103.

- ^ Baumrind, D. (1978). "Parental disciplinary patterns and social competence in children". Youth and Society. 9: 238–276.

- ^ McKay M (2006). Parenting practices in emerging adulthood: Development of a new measure. Thesis, Brigham Young University. Retrieved 2009-06-14.

- ^ Santrock, J.W. (2007). A topical approach to life-span development, third Ed. New York: McGraw-Hill.

- ^ a b Fletcher, A. C.; Walls, J. K.; Cook, E. C.; Madison, K. J.; Bridges, T. H. (December 2008). "Parenting Style as a Moderator of Associations Between Maternal Disciplinary Strategies and Child Well-Being" (PDF). Journal of Family Issues. 29 (12): 1724–1744. doi:10.1177/0192513X08322933.

- ^ a b Brown, Lola; Iyengar, Shrinidhi (2008). "Parenting Styles: The Impact on Student Achievement". Marriage & Family Review. 43 (1–2): 14–38. doi:10.1080/01494920802010140.

- ^ Finkelhor, D.; Ormrod, R.; Turner, H.; Holt, M. (November 2009). "Pathways to Poly-Victimization" (PDF). Child Maltreatment. 14 (4): 316–329. doi:10.1177/1077559509347012.

- ^ Bolin, Inge. Growing Up in a Culture of Respect: Child Rearing in Highland Peru. Austin: University of Texas Press, 2006. Project MUSE.

- ^ a b Day, Nicholas (30 April 2013). "Cultural differences in how you look and talk at your baby". Slate. Retrieved 3 May 2013.

- ^ a b Heidi Keller, Relindis Yovsi, Joern Borke, Joscha Kärtner, Henning Jensen, and Zaira Papaligoura (November/December 2004) "Developmental Consequences of Early Parenting Experiences: Self-Recognition and Self-Regulation in Three Cultural Communities." Child Development. Volume 75, Number 6, pages 1745–1760. Lay summary.

- ^ Bolin, Inge. Growing Up in a Culture of Respect: Child Rearing in Highland Peru. Austin: University of Texas Press, 2006. Project MUSE. Web. 13 May. 2014. <http://muse.jhu.edu/>.

- ^ http://www.ccl-cca.ca/pdfs/LessonsInLearning/Dec-13-07-Parenting-styles.pdf

- ^ Virginia Satir (1972). Peoplemaking. Science and Behaviour Books. ISBN 0-8314-0031-5. Chapter 13: The family blueprint: Your design for peoplemaking, pages 196–224, quote from pages 202–203

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Day, Nicholas (10 April 2013). "Parental ethnotheories and how parents in America differ from parents everywhere else". Slate. Retrieved 19 April 2013.

- ^ Day, Nicholas (9 April 2013). "Give Your Baby a Machete". Slate. Retrieved 19 April 2013.

- ^ Rogoff, B. (2003). The cultural nature of human development. Oxford; New York: Oxford University Press

- ^ Bolin, Inge (2006). Growing Up in a Culture of Respect: Child Rearing in Highland Peru. University of Texas Press. pp. 63–67. ISBN 978-0-292-71298-0.

- ^ Robert K. Thomas. 1958. "Cherokee Values and World View" Unpublished MS, University of North Carolina Available at: http://works.bepress.com/robert_thomas/40

- ^ Bolin, Inge. Growing Up in a Culture of Respect: Child Rearing in Highland Peru. Austin: University of Texas Press, 2006. Project MUSE. Web. 13 May. 2014. <http://muse.jhu.edu/>.

- ^ Archibald,Jo-Ann, (2008). Indigenous Storywork: Educating The Heart, Mind, Body and Spirit. Vancouver, British Columbia: The University of British Columbia Press.

- ^ Concha Delgado-Gaitan Anthropology & Education Quarterly, Vol. 25, No. 3, Alternative Visions of Schooling: Success Stories in Minority Settings (Sep., 1994), pp. 298-316

- ^ Brown, P. (2002). Everyone has to lie in Tzeltal. (pp. 241-275) Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers, Mahwah, NJ.

- ^ a b c Source: Chisholm, J. S. (1996). Learning “respect for everything”: Navajo images of development. Images of childhood, 167–183.

- ^ Paradise, Ruth; Rogoff, Barbara. "Side by Side: Learning by Observing and Pitching In". Journal of the Society of Psychological Anthropology: 102–137.

- ^ Gaskins, Suzanne; Paradise, Ruth (2010). "Learning Through Observation in Daily Life". In Lancy, David; Bock, John; Gaskins, Suzanne (eds.). The Anthropology of Learning in Childhood. United Kingdom: AltaMira

Press.

{{cite book}}: line feed character in|publisher=at position 10 (help) - ^ "Price of raising a child/year". Reuters.com. 4 August 2009. Retrieved 2 May 2012.

- ^ Going Beyond Birthing Classes, Giles Manley, M.D., J. D., F.A.C.O.G. and Howard Janet, JD, provided by CP Family Network http://www.cpfamilynetwork.org/going-beyond-birthing

- ^ "Songs of Innocence and of Experience, copy AA, object 25 (Bentley 25, Erdman 25, Keynes 25) "Infant Joy"". William Blake Archive. Retrieved 16 January 2014.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|editors=ignored (|editor=suggested) (help) - ^ Gartner LM (February 2005). "Breastfeeding and the Use of Human Milk". Pediatrics. 115 (2): 496–506. doi:10.1542/peds.2004-2491. PMID 15687461.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ SS, Hamilton. "Result Filters." National Center for Biotechnology Information. U.S. National Library of Medicine, 1 Oct. 2008. Web. 13 Mar. 2013.

- ^ "The Terrible Twos Explained - Safe Kids (UK)". Safe Kids. 10 May 2011. Retrieved 2 May 2012.

- ^ "UKfamily and Raisingkids have closed". Ukfamily.co.uk. Retrieved 2 May 2012.

- ^ Pitman, Teresa. "Toddler Frustration". Todaysparent. Retrieved 3 December 2011.

- ^ Kenneth R. Ginsburg, MD, MSEd. "The Importance of Play in Promoting Healthy Child Development and Maintaining Strong Parent-Child Bonds" (PDF). American Academy of Pediatrics.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Press Release: "Troubled Teen Son..." 2009[dead link]

- ^ Gilbert, D.T., Schacter, D.L., & Wegner, D.M. (2011). Psychology. New York, NY:Worth Publishers.

External links

- On the Paradoxes of Modern Parenthood (2014-06-05), Zoë Heller, London Review of Books, Vol. 36 No. 11, pages 33–35