England 2018 FIFA World Cup bid: Difference between revisions

Cyberbot II (talk | contribs) Rescuing 1 sources. #IABot |

|||

| Line 52: | Line 52: | ||

* Adequate transport links to the city itself and to the other host cities |

* Adequate transport links to the city itself and to the other host cities |

||

* A high standard of environmental and sustainability initiatives |

* A high standard of environmental and sustainability initiatives |

||

* Support of the public in the city along with the regional media<ref>{{cite web |

* Support of the public in the city along with the regional media<ref>{{cite web|title=Choosing England's Host Cities |url=http://www.england2018bid.com/theroadto2018/hostcity |date=15 June 2009 |publisher=England2018 |accessdate=15 June 2009 |deadurl=yes |archiveurl= |archivedate=1 January 1970 }}</ref> |

||

==Venues== |

==Venues== |

||

Revision as of 02:19, 2 March 2016

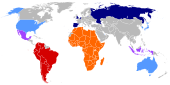

England 2018 was the Football Association's unsuccessful bid for the right to host the 2018 FIFA World Cup.[1] FIFA invited bidding countries to bid for either the 2018 or the 2022 finals, or both. The FA initially decided to bid for both, but with the withdrawal of all non-European bids for the 2018 event, this bid, and that of all other European bidding nations, were effectively disqualified from eligibility for the 2022 edition.

England's bid was managed by England 2018/2022 Bidding Nation Ltd. This company was established by The FA for the purpose of bringing the World Cup tournament to England for the first time since 1966. England attempted to host the 2006 FIFA World Cup but lost out to Germany. England hosted the 1966 FIFA World Cup and had the campaign been successful, England would have become the sixth nation to host the World Cup for a second time.[2] It won the right to host Euro '96. Andy Anson, England 2018 Chief Executive, called for humility with England's bid claiming they "must not fall victim to arrogance" and that lessons had been learned from the unsuccessful attempt to host the 2006 competition. Anson stated that "the tone of this campaign has to be different.[3]

Bid team

The board of England 2018 was chaired by Lord Triesman, chairman of The FA, who has since resigned. He was joined by Geoffrey Thompson, vice president of FIFA; Lord Mawhinney, chairman of the Football League; Paul Elliott, who is the chairman of the Advisory Group to the bid; and Lord (Sebastian) Coe, who led London's successful bid for the 2012 Olympic Games and Paralympic Games, is chairman of LOCOG, and who took leave of absence from his role as chairman of FIFA's ethics committee to join the bid team. The chief executive of England 2018 was Andy Anson, formerly chief executive for Europe of the ATP, and previously commercial director of Manchester United.[4]

The non-executive and subsidiary Advisory Group to the bid consisted of Karren Brady, former managing director of Birmingham City; Martin Sorrell, chief executive of WPP; David Gill, chief executive of Manchester United; the former Minister for Sport, Gerry Sutcliffe and Sir Keith Mills, deputy chairman of the London Organising Committee for the Olympic Games (LOCOG).[5]

The bid had the support of Prince William, the FA's president. The vice presidents of England's 2018 bid team were David Beckham, England international and the country's second most capped player; John Barnes, a former England international; England manager Fabio Capello; Hope Powell, manager of the England women's team; Peter Kenyon, chief executive of Chelsea; Gordon Taylor, chief executive of the PFA; Terry Leahy, the chief executive of Tesco; and economist Nicholas Stern.[6]

The England World Cup bid also received the assistance of Ronnie Flanagan as an advisor on safety and security.[7]

Schedule

| Date | Notes |

|---|---|

| 15 January 2009 | Applications formally invited |

| 2 February 2009 | Closing date for registering intention to bid |

| 16 March 2009 | Deadline to submit completed bid registration forms |

| 14 May 2010 | Deadline for submission of full details of bid |

| 23–26 August 2010 | Inspection committee visited England[8] |

| 2 December 2010 | FIFA appointed hosts for 2018 and 2022 World Cups |

The FA announced its intention to bid on 31 October 2007, and the Bid Registration Form was issued to FIFA's headquarters in Zurich on 17 March 2009. Detailed applications needed to be submitted to FIFA by December 2009, with the final submission of full details of the bid being sent by 14 May 2010. The host countries of the 2018 and 2022 World Cup tournaments were announced in December 2010.[9]

England's bid was officially presented for the first time on 18 May 2009 by Adrian Chiles in the Bobby Moore Room at Wembley Stadium.[10] England players from past and present including Wayne Rooney and Sir Bobby Charlton gave their support with Prime Minister Gordon Brown, along with the support of Conservative Party leader David Cameron and Liberal Democrats leader Nick Clegg. The presentation also received an endorsement from West Ham's Italian manager Gianfranco Zola and he believed that England 'would be a great place to play a World Cup'.[11] After the presentation, the bid team spoke with representatives from each of the fifteen potential host cities.

Details

One host city may have two designated World Cup stadiums though all others may have only one stadium in use. However, England's bid can contain more than one city with two stadiums or more.[12] Now that the England bid team has put forward a number of potential host cities and venues, it is now the decision of FIFA to choose the final list of cities and stadia in late 2010. This would outline the venues of the World Cup if England were chosen to host the tournament.[13]

Stadiums must also be able to accommodate a 20,000 square feet (1,900 m2) hospitality village no more than 150 metres from the stadium. They must have a capacity of at least 40,000 for group and second round matches and 60,000 for quarter finals and beyond,[14] while the final must be played at a venue with a capacity of 80,000.[15]

With regard to selecting a host city, FIFA and the England 2018 bid team assessed the candidates' capabilities to deliver on a number of areas including:

- A range of suitable hotel accommodation

- Training and base camp facilities

- A dedicated fan park with giant screen for the duration of the tournament

- VIP hospitality facilities located in the city centre

- Adequate transport links to the city itself and to the other host cities

- A high standard of environmental and sustainability initiatives

- Support of the public in the city along with the regional media[16]

Venues

A total of fifteen stadia from twelve cities were proposed to FIFA. Had England's bid been successful, the final decision on which would host matches would have been made in 2013. Three stadia would have been forwarded from London: Wembley Stadium, Arsenal's Emirates Stadium and either the Olympic Stadium or Tottenham Hotspur's yet-to-be-built new ground (if the latter were ready). At the time of bidding, the Olympic Stadium was under construction the Olympic games in 2012; its future following the Olympics was unclear and beyond the control of the World Cup bid committee, and so the Tottenham ground was put forward alongside it. It was not made clear during the bid which stadium would have been preferred had both stadia been viable candidates in 2013.[13]

The other stadia that were nominated were Sunderland's Stadium of Light, Birmingham's Villa Park, the New Nottingham Forest Stadium, Elland Road in Leeds, Sheffield's Hillsborough Stadium, St James' Park in Newcastle, the new Bristol City Stadium, Plymouth's Home Park, Old Trafford and the City of Manchester Stadium in Manchester, and, in Liverpool, either the existing Anfield or the proposed Stanley Park Stadium. In the case of Liverpool, the bid committee determined that the current Anfield stadium would have been, with minor improvements, acceptable for World Cup matches; however, because of Liverpool FC's plans to build a new ground, the committee specified that the new stadium would take the place of Anfield if it were ready in time.[13]

Many of the stadia selected would have required minor modernisation in order to meet the strict requirements for holding World Cup tournament games, as is usual for all pre-existing stadia. The grounds in Leeds, Sheffield, Milton Keynes and Plymouth in particular were all set for an increase in capacity, whilst new stadiums proposed in Nottingham and Bristol were a part of the bid.

a: Stadium used in 1966 FIFA World Cup

b: Stadium used in UEFA Euro '96

Rejected bid venues

Before the final decision was made by a 'technical panel', Derby,[26] Kingston upon Hull,[27] Leicester[28] and Portsmouth[29] (who later withdrew)[30] were also among the list of possible venues until the 12 'final cities' were announced on 16 December 2009.[31]

Official bid partners

Outcome and reaction

England's bid for the World Cup was unsuccessful, only receiving 2 out of 22 votes from the FIFA executive committee in the first round of voting. The rights to host the 2018 World Cup were eventually awarded to Russia.

At a conference in Qatar in March 2012, Premier League chairman and deputy chairman of the 2018 bid, Dave Richards, said FIFA allowed the FA to waste money on their 2018 World Cup bid when, he claimed, they had little chance of winning it, stating "Why couldn't FIFA have said we want to take it to the Gulf? We spent £19m on that bid. When we went for it everybody believed we had a chance. But, as we went through it, a pattern emerged that suggested maybe we didn't."[32] The Football Association and the Premier League distanced themselves from Richards' remarks, stressing that he was attending the conference in a personal capacity.

References

- ^ White, Duncan (16 May 2009). "David Beckham will kick off England's 2018 World Cup bid". Telegraph.co.uk. London: Telegraph Media Group. Retrieved 17 May 2009.

- ^ "BBC Sport: The race to host World Cup 2018". BBC. 17 March 2009. Retrieved 11 February 2009.

- ^ "2018 bid chief calls for humility". BBC Sport. 18 May 2009. Retrieved 18 May 2009.

- ^ "Re-Structuring of Bid Revealed". Australian FourFourTwo. 13 November 2009. Retrieved 13 July 2012.

- ^ Sale, Charles (13 November 2009). "Lord Triesman's calamitous World Cup 2018 campaign team dodge the big issues". The Daily Mail. Associated Newspapers. Retrieved 13 July 2012.

- ^ "England Brings together 2018 World Cup team" (PDF). Communiqué: The Football Association's International News Letter (23). The Football Association: 1, 3. 2008.

- ^ "Sir Ronnie Flanagan joins England's bid team". England2018bid.com. 22 June 2009. Retrieved 24 June 2009. [dead link]

- ^ "FIFA receives bidding documents for 2018 and 2022 FIFA World Cups" (Press release). FIFA.com. 14 May 2010. Retrieved 31 July 2010.

- ^ "England confirms bid for 2018 World Cup". Soccer News Info. 27 January 2009. Retrieved 15 June 2009.

- ^ "2018 bid chief calls for humility". BBC Sport. 18 May 2009. Retrieved 18 May 2009.

- ^ "West Ham boss Zola backs England World Cup bid". Tribal Football. 20 May 2009. Retrieved 15 June 2009.

- ^ "Cities make case to be in England's 2018 World Cup bid". BBC Sport. 26 November 2009. Retrieved 27 November 2009.

- ^ a b c "Milton Keynes part of England's 2018 World Cup bid". BBC Sport. 6 December 2009. Retrieved 16 December 2009.

- ^ Kelso, Paul (26 May 2009). "London Olympic Stadium possible venue for 2018 World Cup". Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 15 June 2009.

- ^ "The race to host World Cup 2018 and 2022". BBC Sport. 17 March 2009. Retrieved 27 November 2009.

- ^ "Choosing England's Host Cities". England2018. 15 June 2009. Retrieved 15 June 2009.

{{cite web}}:|archive-date=requires|archive-url=(help); Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Arsenal may expand Emirates". The Guardian. London: Guardian News and Media. 25 September 2007. Retrieved 13 July 2012.

- ^ http://www.bluedays.co.uk/2010/02/26/eastlands-redevelopment-to-include-city-stadium-expansion/

- ^ "New Man City owners keen to discuss expansion plans". Oddspreview. Retrieved 26 February 2009.

- ^ "Sunderland AFC: Stadium of Light". Football Ground Guide. Retrieved 8 February 2010.

- ^ Aston Local Plan

- ^ "Hillsborough – a vision of the future". Sheffield Wednesday FC official website. Retrieved 19 August 2009.

- ^ "Leeds United: Elland Road for World Cup Artists Impressions". Yorkshire Evening Post. Retrieved 8 February 2010.

- ^ "World Cup Stadium Plans Unveiled". MK Dons.com. 7 February 2010. Retrieved 7 February 2010, 2009.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ Home Park Vision Plymouth Argyle FC. Retrieved 21 January 2010.

- ^ "Derby identify kids as crucial to bid success". England2018bid.com. 27 July 2009. Retrieved 3 August 2010.

- ^ "World Cup: Hull misses out on World Cup". Hull Daily Mail. 16 December 2009. Retrieved 3 August 2010.

- ^ "Leicester kicks-off Host City bid". England2018bid.com. 9 June 2009. Retrieved 3 August 2010.

- ^ "Portsmouth launches host city bid". England2018bid.com. 9 June 2009. Retrieved 3 August 2010.

- ^ "Portsmouth withdraw from Host City Process". England2018bid.com. 25 November 2009. Retrieved 3 August 2010.

- ^ "Candidate Host Cities revealed". England2018bid.com. 9 December 2009. Retrieved 3 August 2010.

- ^ "Dave Richards sorry for comments about Fifa and Uefa". BBC Sport. 14 March 2012. Retrieved 15 March 2012.