Flashdance: Difference between revisions

Rescuing 2 sources and tagging 0 as dead. #IABot (v1.5.4) |

|||

| Line 149: | Line 149: | ||

In March 2001, a [[Broadway theatre|Broadway]] musical version was proposed with new songs by [[Giorgio Moroder]], but failed to materialize.<ref>{{cite news| url=http://www.variety.com/article/VR1117795691.html?categoryid=15&cs=1 | work=Variety | title=What a feeling: 'Flashdance' fever | first=Robert | last=Hofler | date=2001-03-22}}</ref> |

In March 2001, a [[Broadway theatre|Broadway]] musical version was proposed with new songs by [[Giorgio Moroder]], but failed to materialize.<ref>{{cite news| url=http://www.variety.com/article/VR1117795691.html?categoryid=15&cs=1 | work=Variety | title=What a feeling: 'Flashdance' fever | first=Robert | last=Hofler | date=2001-03-22}}</ref> |

||

In July 2008, a stage musical adaptation ''[[Flashdance The Musical]]'' premiered at the [[Theatre Royal, Plymouth|Theatre Royal]] in [[Plymouth]], [[England]]. The [[libretto|book]] is co-written by [[Thomas Hedley|Tom Hedley]], who created the story outline for the original film, and the [[choreography]] is by [[Arlene Phillips]].<ref name="stageversion">{{cite news | last= |

In July 2008, a stage musical adaptation ''[[Flashdance The Musical]]'' premiered at the [[Theatre Royal, Plymouth|Theatre Royal]] in [[Plymouth]], [[England]]. The [[libretto|book]] is co-written by [[Thomas Hedley|Tom Hedley]], who created the story outline for the original film, and the [[choreography]] is by [[Arlene Phillips]].<ref name="stageversion">{{cite news | last=Atkins | first=Tom | title=Flashdance Debuts in Plymouth, Sweeney Shouts | publisher=WhatsOnStage | date=2008-02-08 | url=http://www.whatsonstage.com/index.php?pg=207&story=E8821202487573 | deadurl=yes | archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20081019014104/http://www.whatsonstage.com/index.php?pg=207&story=E8821202487573 | archivedate=October 19, 2008 | df=mdy-all }}</ref> |

||

===''Flashdance'' and the MTV connection=== |

===''Flashdance'' and the MTV connection=== |

||

| Line 161: | Line 161: | ||

;Suit against Jennifer Lopez and filmmakers over music video |

;Suit against Jennifer Lopez and filmmakers over music video |

||

In 2003, following the use of dance routines from the film by [[Jennifer Lopez]] in her music video "[[I'm Glad]]" (directed by [[David LaChapelle]]), Marder sued Lopez, [[Sony|Sony Corporation]] (the makers of the music video), and Paramount in an attempt to gain a [[copyright]] interest in the film. Although Lopez argued that her video for "I'm Glad" was intended as a tribute to ''Flashdance'', in May 2003 Sony agreed to pay a licensing fee to Paramount for the use of dance routines and other story material from the film in the video.<ref>[http://www.imdb.com/title/tt0085549/news Flashdance (1983) - News<!-- Bot generated title -->]</ref><ref>{{cite web|url= |

In 2003, following the use of dance routines from the film by [[Jennifer Lopez]] in her music video "[[I'm Glad]]" (directed by [[David LaChapelle]]), Marder sued Lopez, [[Sony|Sony Corporation]] (the makers of the music video), and Paramount in an attempt to gain a [[copyright]] interest in the film. Although Lopez argued that her video for "I'm Glad" was intended as a tribute to ''Flashdance'', in May 2003 Sony agreed to pay a licensing fee to Paramount for the use of dance routines and other story material from the film in the video.<ref>[http://www.imdb.com/title/tt0085549/news Flashdance (1983) - News<!-- Bot generated title -->]</ref><ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.davidlachapelle.com/press/nytimes2.shtml |title=D A V I D * L A C H A P E L L E |publisher=Web.archive.org |date= |accessdate=2017-06-28 |deadurl=bot: unknown |archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20061019144646/http://www.davidlachapelle.com/press/nytimes2.shtml |archivedate=October 19, 2006 |df=mdy-all }}</ref> |

||

==See also== |

==See also== |

||

Revision as of 03:32, 2 October 2017

| Flashdance | |

|---|---|

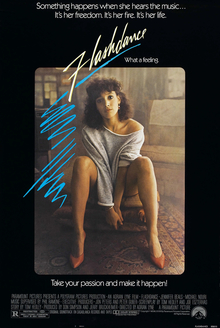

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Adrian Lyne |

| Screenplay by | |

| Story by | Tom Hedley |

| Produced by |

|

| Starring | |

| Cinematography | Donald Peterman |

| Edited by | |

| Music by | Giorgio Moroder |

Production companies | |

| Distributed by | Paramount Pictures |

Release date |

|

Running time | 97 minutes[1] |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $7 million |

| Box office | $201.5 million[2] |

Flashdance is a 1983 American romantic drama film directed by Adrian Lyne. It was the first collaboration of producers Don Simpson and Jerry Bruckheimer, and the presentation of some sequences in the style of music videos was an influence on other 1980s films including Top Gun (1986), Simpson and Bruckheimer's most famous production. Flashdance opened to negative reviews by professional critics, but was a surprise box office success, becoming the third highest-grossing film of 1983 in the United States.[3][4] It had a worldwide box-office gross of more than $100 million.[5] Its soundtrack spawned several hit songs, including "Maniac" (performed by Michael Sembello), and the Academy Award–winning "Flashdance... What a Feeling" (performed by Irene Cara), which was written for the film.

Plot

Alexandra "Alex" Owens (Jennifer Beals) is an eighteen-year-old welder at a steel mill in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, who lives with her dog Grunt in a converted warehouse. Although she aspires to become a professional dancer, she has no formal dance training, and works as a exotic dancer by night at Mawby's, a neighborhood bar and grill which hosts a nightly cabaret.

Lacking family, Alex forms bonds with her coworkers at Mawby's, some of whom also aspire to greater artistic achievements. Jeanie (Sunny Johnson), a waitress, is training to be a figure skater, while her boyfriend, short-order cook Richie (Kyle T. Heffner), wishes to become a stand up comic.

One night, Alex catches the eye of customer Nick Hurley (Michael Nouri), the owner of the steel mill where she works. After learning that Alex is one of his employees, Nick begins to pursue her on the job, though Alex turns down his advances at first. Alex is also approached by Johnny C. (Lee Ving), who wants Alex to dance at his nearby strip club, Zanzibar.

After seeking counsel from her mentor Hanna Long (Lilia Skala), a retired ballerina, Alex attempts to apply to the Pittsburgh Conservatory of Dance and Repertory. Alex becomes intimidated by the scope of the application process, which includes listing all prior dance experience and education, and she leaves without applying.

Leaving Mawby's one evening, Richie and Alex are assaulted by Johnny C. and his bodyguard, Cecil. Nick intervenes, and after taking Alex home, the two begin a relationship.

At a skating competition in which she is competing, Jeanie falls twice during her performance and sits defeated on the ice and has to be helped away. Later, feeling she will never achieve her dreams, and after Richie has left Pittsburgh to try to become a comic in Los Angeles, Jeanie begins going out with Johnny C. and works for him as a Zanzibar stripper. Finding out that she is dancing nude, Alex drags her out while she protests and cries.

After seeing Nick with a woman at the ballet one night, Alex throws a rock through one of the windows of his house, only to discover that it was his ex-wife (Belinda Bauer) whom he was meeting for a charity function. Alex and Nick reconcile, and she gains the courage to apply for entrance to the Conservatory. Nick uses his connections with the arts council to get Alex an audition. Alex is furious with Nick, since she did not get the opportunity based on her own merit and decides not to go through with the audition. Seeing the results of others' failed dreams and after the sudden death of Hanna, Alex becomes despondent about her future, but finally decides to go through with the audition.

At the audition, Alex initially falters, but begins again, and she successfully completes a dance number composed of various aspects of dance she has studied and practiced, including breakdancing which she has seen on the streets of Pittsburgh. The board responds favorably, and Alex is seen joyously emerging from the Conservatory to find Nick and Grunt waiting for her with a bouquet of roses.

Cast

- Jennifer Beals as Alexandra "Alex" Owens

- Michael Nouri as Nick Hurley

- Lilia Skala as Hanna Long

- Sunny Johnson as Jeanie Szabo

- Kyle T. Heffner as Richie Plasic

- Lee Ving as Johnny C.

- Ron Karabatsos as Jake Mawby

- Belinda Bauer as Katie Hurley

- Malcolm Danare as Cecil

- Phil Bruns as Frank Szabo

- Micole Mercurio as Rosemary Szabo

- Lucy Lee Flippin as Secretary

- Don Brockett as Pete

- Cynthia Rhodes as Tina Tech

- Durga McBroom as Heels

- Stacey Pickren as Margo

- Liz Sagal as Sunny

- Marine Jahan (uncredited) as Alexandra Owens in dance sequences

Music

"Flashdance... What a Feeling" was performed by Irene Cara, who also sang the title song for the similar 1980 film Fame. The music for "Flashdance... What a Feeling" was composed by Giorgio Moroder, and the lyrics were written by Cara and Keith Forsey. The song won an Academy Award for Best Original Song, as well as a Golden Globe and numerous other awards. It also reached number one on the Billboard Hot 100 in May 1983. Despite the song's title, the word "Flashdance" itself is not heard in the lyrics. The song is used in the opening title sequence of the film, and is the music Alex uses in her dance audition routine at the end of the film.

Another song used in the film, "Maniac", was also nominated for an Academy Award. It was written by Michael Sembello and Dennis Matkosky. A popular urban legend holds that the song was originally written for the 1980 horror film Maniac, and that lyrics about a killer on the loose were rewritten so the song could be used in Flashdance. The legend is discredited in the special features of the film's DVD release, which reveal that the song was written for the film, although only two complete lyrics ("Just a steel town girl on a Saturday night" and "She's a maniac") were available when filming commenced. Like the title song, it reached number one on the Billboard Hot 100 in September 1983.[6][7]

Other songs in the film include "Lady, Lady, Lady", performed by Joe Esposito, "Gloria" and "Imagination" performed by Laura Branigan, and "I'll Be Here Where the Heart Is", performed by Kim Carnes.

The soundtrack album of Flashdance sold 700,000 copies during its first two weeks on sale and has gone on to sell over 6,000,000 copies in the US alone. In 1984, the album won the Grammy Award for Best Album of Original Score Written for a Motion Picture or a Television Special.

Production

Adrian Lyne, whose background was primarily in directing television commercials, was not the first choice as director of Flashdance. David Cronenberg turned down an offer to direct the film, as did Brian De Palma, who instead chose to direct Scarface (1983). Executives at Paramount were unsure about the film's potential and sold 25% of the rights prior to its release.[8]

Flashdance is often remembered for the sweatshirt with a large neck hole that Beals wore on the poster advertising the film. Beals said that the look of the sweatshirt came about by accident when it shrank in the wash and she cut out a large hole at the top so that she could wear it again.[9]

Casting

Three candidates, Jennifer Beals, Demi Moore, and Leslie Wing, were the finalists for the role of Alex Owens. Two different stories exist regarding how Beals was chosen. One states that then-Paramount president Michael Eisner asked women secretaries at the studio to select their favorite after viewing screen tests. The other: the film's scriptwriter Joe Eszterhas claims that Eisner asked "two hundred of the most macho men on the [Paramount] lot, Teamsters and gaffers and grips ... 'I want to know which of these three young women you’d most want to f---'".[10]

The role of Nick Hurley was originally offered to KISS lead man Gene Simmons, who turned it down because it would conflict with his "demon" image. Pierce Brosnan, Robert De Niro, Richard Gere, Mel Gibson, Tom Hanks, and John Travolta were also considered for the part. Kevin Costner, a struggling actor at the time, came very close for the role of Nick Hurley, that went to Michael Nouri.

Crew

Flashdance was the first success of a number of filmmakers who became top industry figures in the 1980s and beyond. The film was the first collaboration between Don Simpson and Jerry Bruckheimer, who went on to produce Beverly Hills Cop (1984) and Top Gun (1986). Eszterhas received his second screen credit for Flashdance, while Lyne went on to direct 9½ Weeks (1986), Fatal Attraction (1987), Indecent Proposal (1993), and Lolita (1997). Lynda Obst, who developed the original story outline, went on to produce Adventures in Babysitting (1987), The Fisher King (1991), and Sleepless in Seattle (1993).

Locations

Much of the film was shot in locations around Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania:

- The ice skating rink on which Jeanie falls was filmed at Monroeville Mall. This was the same ice skating rink used in the George A. Romero horror film Dawn of the Dead (1978).

- The fictional Pittsburgh Conservatory of Dance and Repertory was filmed inside the lobby and in front of Carnegie Music Hall, a part of the Carnegie Museum of Art, located near the campuses of Carnegie Mellon University and the University of Pittsburgh Oakland.

- Alex's apartment was located in the South Side neighborhood of Pittsburgh.

- Alex is seen riding one of the Duquesne Incline cable cars when she goes to visit Hannah.

- Hannah's apartment is located at 2100 Sidney Street at the southeast corner of South 21st Street. The entrance to the apartment is from South 21st Street.

- The opening sequence of scenes with Alex riding her bicycle starts on Warren Street at its intersection with Catoma Street. She rides south on Warren Street to Henderson Street, makes a hairpin turn from Henderson Street onto Fountain Street, and is next shown riding south on Middle Street. The last scene of the sequence shows Alex riding east over the Smithfield Street Bridge, which is a continuity error.

Reception

Critical response

Flashdance has received mostly unfavorable reviews from professional critics. It currently holds a Rotten Tomatoes approval rating of 33%, based on 39 reviews with the consensus: "All style and very little substance, Flashdance boasts eye-catching dance sequences—and benefits from an appealing performance from Jennifer Beals—but its narrative is flat-footed".[11] Roger Ebert placed it on his list of Most Hated films, stating: "Jennifer Beals shouldn't feel bad. She is a natural talent, she is fresh and engaging here, and only needs to find an agent with a natural talent for turning down scripts".[12] Halliwell's Film Guide gave it one star out of four while The New Yorker described the film as "Basically, a series of rock videos." The Guardian described it as "A preposterous success." Detractors of the film argue that in addition to the shallow plot, the film represents the worst excesses of 1980s film making with its emphasis on short sequences and rapid editing between shots. The screenplay of the film was nominated for a Razzie Award, where it lost to The Lonely Lady. A common criticism was directed toward the on-screen partnership between Jennifer Beals and Michael Nouri, largely due to the significant age difference between the two (at the time of filming, Beals was 18 while Nouri was 36). Critics have also questioned whether an 18-year-old woman would have been given a job as a welder in an old-fashioned steel mill.

The dimly lit cinematography and montage-style editing are due in part to the fact that most of Jennifer Beals' dancing in the film was performed by a body double.[13] Her main dance double is the French actress Marine Jahan, while the breakdancing that Alex performs in the audition sequence at the end of the film was doubled by the male dancer Crazy Legs. The shot of Alex diving through the air in slow motion during the audition sequence was performed by Sharon Shapiro, who was a professional gymnast.

Accolades

The film is recognized by American Film Institute in these lists:

- 2004: AFI's 100 Years...100 Songs:

- "Flashdance... What a Feeling" – #55[14]

- 2006: AFI's 100 Years...100 Cheers – Nominated[15]

Legacy

Sequel

There were discussions about a sequel, but the film was never made. Beals turned down an offer to appear in a sequel, saying: "I've never been drawn to something by virtue of how rich or famous it will make me. I turned down so much money, and my agents were just losing their minds."[16]

Musical adaptation

In March 2001, a Broadway musical version was proposed with new songs by Giorgio Moroder, but failed to materialize.[17]

In July 2008, a stage musical adaptation Flashdance The Musical premiered at the Theatre Royal in Plymouth, England. The book is co-written by Tom Hedley, who created the story outline for the original film, and the choreography is by Arlene Phillips.[18]

Flashdance and the MTV connection

Flashdance is not a musical in the traditional sense as the characters do not sing, but rather, the songs are presented in the style of self-contained music videos. The success of this film is attributed in part to the 1981 launch of the cable channel MTV (Music Television), as it was the first to exploit the new medium effectively. By excerpting segments of the film and running them as music videos on MTV, the studio benefited from extensive free promotion, and thus established the new medium as an important marketing tool for movies.

In the mid-1980s, it became almost obligatory to release a music video to promote a major motion picture—even if the film were not especially suited for one.[19] An example from the era is the song and music video "Take My Breath Away" from Top Gun (1986), also from Flashdance producers Don Simpson and Jerry Bruckheimer. Giorgio Moroder composed "Take My Breath Away" and several of the songs for Flashdance.

Legal action

- Suit against the filmmakers

Flashdance was inspired by the real-life story of Maureen Marder, a construction worker/welder by day and dancer by night in a Toronto strip club. Like Alex Owens in the film, she aspired to enroll in a prestigious dance school. Tom Hedley wrote the original story outline for Flashdance, and on December 6, 1982, Marder signed a release document giving Paramount Pictures the right to portray her life story on screen, for which she was given a one-off payment of $2,300. Flashdance is estimated to have grossed more than $200 million worldwide. In June 2006, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit in San Francisco affirmed a lower court's ruling that Marder gave up her rights to the film when she signed the release document in 1982. The panel of three judges stated in its ruling: "Though in hindsight the agreement appears to be unfair to Marder—she only received $2,300 in exchange for a release of all claims relating to a movie that grossed over $150 million—there is simply no evidence that her consent was obtained by fraud, deception, misrepresentation, duress or undue influence." The court also noted that Marder's attorney had been present when she signed the document.[20]

- Suit against Jennifer Lopez and filmmakers over music video

In 2003, following the use of dance routines from the film by Jennifer Lopez in her music video "I'm Glad" (directed by David LaChapelle), Marder sued Lopez, Sony Corporation (the makers of the music video), and Paramount in an attempt to gain a copyright interest in the film. Although Lopez argued that her video for "I'm Glad" was intended as a tribute to Flashdance, in May 2003 Sony agreed to pay a licensing fee to Paramount for the use of dance routines and other story material from the film in the video.[21][22]

See also

- It's Flashbeagle, Charlie Brown

- List of American films of 1983

- Duquesne Brewery Clock

- Dance, Girl, Dance

- Films of a similar genre in the 1980s

- Fame (1980)

- Staying Alive (1983)

- Footloose (1984)

- Purple Rain (1984)

- Desperately Seeking Susan (1985)

- Girls Just Want to Have Fun (1985)

- The Last Dragon (1985)

- Dirty Dancing (1987)

References

- ^ "FLASHDANCE (15)". British Board of Film Classification. April 27, 1983. Retrieved July 8, 2015.

- ^ Box Office Information for Flashdance. The Numbers. Retrieved March 17, 2013.

- ^ Ebert, Roger. "Roger Ebert's ''Most Hated'' list". Rogerebert.suntimes.com. Retrieved June 28, 2017.

- ^ http://www.boxofficemojo.com/yearly/chart/?yr=1983&p=.htm

- ^ Litwak, Mark (1986). Reel Power: The Struggle for Influence and Success in the New Hollywood. New York: William Morrow & Co. p. 91. ISBN 0-688-04889-7.

- ^ "Maniac by Michael Sembello Songfacts". Songfacts.com. Retrieved June 28, 2017.

- ^ "Billboard Charts Archive - 1983". Billboard. Retrieved February 9, 2015.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ Flashdance (1983) - Trivia

- ^ Rob Salem (February 16, 2011). "Jennifer Beals: From ripped sweats to dress blues - thestar.com". www.thestar.com. Retrieved February 27, 2011.

- ^ Thomas, Mike (January 20, 2011). "Jennifer Beals returns to Chicago with new cop drama". Chicago Sun-Times. Retrieved May 4, 2012.

- ^ "Flashdance". Rotten Tomatoes/Flixster. Retrieved September 28, 2013.

- ^ "Roger Ebert's review of Flashdance". Chicago Sun-Times. July 23, 2007.

- ^ Dancer not getting credit for work in "Flashdance" The Ledger April 22, 1983

- ^ "AFI's 100 Years...100 Songs" (PDF). American Film Institute. Retrieved August 14, 2016.

- ^ "AFI's 100 Years...100 Cheers Nominees" (PDF). Retrieved August 14, 2016.

- ^ Beals Turned Down Flashdance Sequel contactmusic.com, August 18, 2003.

- ^ Hofler, Robert (March 22, 2001). "What a feeling: 'Flashdance' fever". Variety.

- ^ Atkins, Tom (February 8, 2008). "Flashdance Debuts in Plymouth, Sweeney Shouts". WhatsOnStage. Archived from the original on October 19, 2008.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Litwak, p. 245

- ^ Herel, Suzanne (June 13, 2006). "SAN FRANCISCO / Inspiration for 'Flashdance' loses appeal for more money". The San Francisco Chronicle.

- ^ Flashdance (1983) - News

- ^ "D A V I D * L A C H A P E L L E". Web.archive.org. Archived from the original on October 19, 2006. Retrieved June 28, 2017.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help)

External links

- Flashdance at IMDb

- Flashdance at the TCM Movie Database

- Flashdance at Box Office Mojo

- Flashdance at Rotten Tomatoes

- 1983 films

- 1980s dance films

- 1980s romantic drama films

- American dance films

- American films

- American romantic drama films

- English-language films

- Fictional portrayals of the Pittsburgh Bureau of Police

- Film scores by Giorgio Moroder

- Films directed by Adrian Lyne

- Films produced by Don Simpson

- Films produced by Jerry Bruckheimer

- Films set in Pittsburgh

- Films shot in Pennsylvania

- Films that won the Best Original Song Academy Award

- Paramount Pictures films

- PolyGram Filmed Entertainment films

- Screenplays by Joe Eszterhas

- Films adapted into plays