Griffin: Difference between revisions

Rescuing 1 sources and tagging 0 as dead. #IABot (v1.6beta3) |

|||

| Line 58: | Line 58: | ||

[[File:Minneteppich KGM.jpg|thumb|Medieval tapestry, [[Basel]], c. 1450]] |

[[File:Minneteppich KGM.jpg|thumb|Medieval tapestry, [[Basel]], c. 1450]] |

||

In [[Central Asia]], the griffin appears about a thousand years after Bronze Age Crete, in the 5th–4th centuries BC, probably originating from the [[Achaemenid Persian Empire]]. The Achaemenids considered the griffin "a protector from evil, witchcraft and secret slander".<ref>Neva, Elena. "[http://www.artwis.com/articles/central-asian-jewelry-and-their-symbols-in-ancient-time/ Central Asian Jewelry and their Symbols in Ancient Time]" Artwis; citing Pugachenkova, G. (1959) "Grifon v drevnem iskusstve central’noi Azii." ''Sovetskya Arheologia,'' 2 pp. 70, 83</ref> The modern generalist calls it the lion-griffin, as for example, [[Robin Lane Fox]], in ''Alexander the Great,'' 1973:31 and notes p. 506, who remarks a lion-griffin attacking a stag in a pebble mosaic [http://greecefsp2009.files.wordpress.com/2009/05/dsc_0175.jpg Dartmouth College expedition] at [[Pella]], perhaps as an emblem of the kingdom of Macedon or a personal one of Alexander's successor [[Antipater]]. |

In [[Central Asia]], the griffin appears about a thousand years after Bronze Age Crete, in the 5th–4th centuries BC, probably originating from the [[Achaemenid Persian Empire]]. The Achaemenids considered the griffin "a protector from evil, witchcraft and secret slander".<ref>Neva, Elena. "[http://www.artwis.com/articles/central-asian-jewelry-and-their-symbols-in-ancient-time/ Central Asian Jewelry and their Symbols in Ancient Time]" Artwis; citing Pugachenkova, G. (1959) "Grifon v drevnem iskusstve central’noi Azii." ''Sovetskya Arheologia,'' 2 pp. 70, 83</ref> The modern generalist calls it the lion-griffin, as for example, [[Robin Lane Fox]], in ''Alexander the Great,'' 1973:31 and notes p. 506, who remarks a lion-griffin attacking a stag in a pebble mosaic <ref>[http://greecefsp2009.files.wordpress.com/2009/05/dsc_0175.jpg Dartmouth College expedition]</ref> at [[Pella]], perhaps as an emblem of the kingdom of Macedon or a personal one of Alexander's successor [[Antipater]]. |

||

The [[Pisa Griffin]] is a large bronze sculpture that has been in [[Pisa]] in Italy since the Middle Ages, though it is of [[Islamic art|Islamic]] origin. It is the largest bronze medieval Islamic sculpture known, at over three feet tall (42.5 inches, or 1.08 m.), and was probably created in the 11th century in [[Al-Andaluz]] (Islamic Spain).<ref>Quantara; Hoffman, 318</ref> From about 1100 it was placed on a column on the roof of [[Pisa Cathedral]] until replaced by a replica in 1832; the original is now in the Museo dell' Opera del Duomo (Cathedral Museum), Pisa. |

The [[Pisa Griffin]] is a large bronze sculpture that has been in [[Pisa]] in Italy since the Middle Ages, though it is of [[Islamic art|Islamic]] origin. It is the largest bronze medieval Islamic sculpture known, at over three feet tall (42.5 inches, or 1.08 m.), and was probably created in the 11th century in [[Al-Andaluz]] (Islamic Spain).<ref>Quantara; Hoffman, 318</ref> From about 1100 it was placed on a column on the roof of [[Pisa Cathedral]] until replaced by a replica in 1832; the original is now in the Museo dell' Opera del Duomo (Cathedral Museum), Pisa. |

||

Revision as of 09:49, 17 November 2017

| |

| Grouping | Mythological hybrids |

|---|---|

| Other name(s) | griffon, gryphon |

The griffin, griffon, or gryphon (Greek: γρύφων, grýphōn, or γρύπων, grýpōn, early form γρύψ, grýps; Template:Lang-lat) is a legendary creature with the body, tail, and back legs of a lion; the head and wings of an eagle; and an eagle's talons as its front feet. Because the lion was traditionally considered the king of the beasts and the eagle the king of birds, the griffin was thought to be an especially powerful and majestic creature. The griffin was also thought of as king of all creatures. Griffins are known for guarding treasure and priceless possessions.[1]

In Greek and Roman texts, griffins and Arimaspians were associated with gold. Indeed, in later accounts, "griffins were said to lay eggs in burrows on the grounds and these nests contained gold nuggets".[2] Adrienne Mayor, a classical folklorist, proposes that the griffin was an ancient misconception derived from the fossilized remains of the Protoceratops found in gold mines in the Altai mountains of Scythia, in present-day southeastern Kazakhstan, or in Mongolia,[3] though this hypothesis has been strongly contested as it ignores pre-Mycenaean accounts.[4] In antiquity it was a symbol of divine power and a guardian of the divine.[5]

Etymology

The derivation of this word remains uncertain. It could be related to the Greek word γρυπός (grypos), meaning 'curved', or 'hooked'. Also, this could have been an Anatolian loan word, compare Akkadian karūbu (winged creature), and similar to Cherub. A related Hebrew word is כרוב (kerúv).[6]

Form

Most statuary representations of griffins depict them with bird-like talons, although in some older illustrations griffins have a lion's forelimbs; they generally have a lion's hindquarters. Its eagle's head is conventionally given prominent ears; these are sometimes described as the lion's ears, but are often elongated (more like a horse's), and are sometimes feathered.

Infrequently, a griffin is portrayed without wings, or a wingless eagle-headed lion is identified as a griffin. In 15th-century and later heraldry, such a beast may be called an alce or a keythong.

In heraldry, a griffin always has forelegs like an eagle's hind-legs. A type of griffin with the four legs of a lion was distinguished by perhaps only one English herald of later heraldry as the Opinicus, which also had a camel-like neck and a short tail that almost resembles a camel's tail.

History

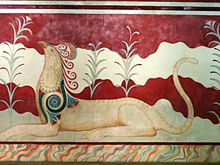

There is evidence of representations of griffins in Ancient Iranian and Ancient Egyptian art dating back to before 3000 BC.[7] In Egypt, a griffin can be seen in a cosmetic palette from Hierakonpolis, known as the "Two Dog Palette",[8][9] which is dated to ca. 3300-3100 BC.[10] In Iran, griffins appeared on cylinder seals from Susa as early as 3000 BC.[11] Griffin depictions appear in the Levant, Syria, and Anatolia in the Middle Bronze Age,[12][13] dated at about 1950-1550 BC.[14] Early depictions of griffins in Ancient Greek art are found in the 15th century BC frescoes in the Throne Room of the Bronze Age Palace of Knossos, as restored by Sir Arthur Evans. It continued being a favored decorative theme in Archaic and Classical Greek art.

In Central Asia, the griffin appears about a thousand years after Bronze Age Crete, in the 5th–4th centuries BC, probably originating from the Achaemenid Persian Empire. The Achaemenids considered the griffin "a protector from evil, witchcraft and secret slander".[15] The modern generalist calls it the lion-griffin, as for example, Robin Lane Fox, in Alexander the Great, 1973:31 and notes p. 506, who remarks a lion-griffin attacking a stag in a pebble mosaic [16] at Pella, perhaps as an emblem of the kingdom of Macedon or a personal one of Alexander's successor Antipater.

The Pisa Griffin is a large bronze sculpture that has been in Pisa in Italy since the Middle Ages, though it is of Islamic origin. It is the largest bronze medieval Islamic sculpture known, at over three feet tall (42.5 inches, or 1.08 m.), and was probably created in the 11th century in Al-Andaluz (Islamic Spain).[17] From about 1100 it was placed on a column on the roof of Pisa Cathedral until replaced by a replica in 1832; the original is now in the Museo dell' Opera del Duomo (Cathedral Museum), Pisa.

Ancient parallels

Several ancient mythological creatures are similar to the griffin. These include the Lamassu, an Assyrian protective deity, often depicted with a bull or lion's body, eagle's wings, and human's head.

Sumerian and Akkadian mythology feature the demon Anzu, half man and half bird, associated with the chief sky god Enlil. This was a divine storm-bird linked with the southern wind and the thunder clouds.

Jewish mythology speaks of the Ziz, which resembles Anzu, as well as the ancient Greek Phoenix. The Bible mentions the Ziz in Psalms 50:11. This is also similar to Cherub. The cherub, or sphinx, was very popular in Phoenician iconography.

In ancient Crete, griffins became very popular, and were portrayed in various media. A similar creature is the Minoan Genius.

In the Hindu religion, Garuda is a large bird-like creature which serves as a mount (vahana) of the Lord Vishnu. It is also the name for the constellation Aquila.

Medieval lore

In legend, griffins not only mated for life, but if either partner died, then the other would continue the rest of its life alone, never to search for a new mate.[citation needed] The griffin was thus made an emblem of the Church's opposition to remarriage.[dubious – discuss] Being a union of an aerial bird and a terrestrial beast, it was seen in Christendom to be a symbol of Jesus, who was both human and divine. As such it can be found sculpted on some churches.[1]

According to Stephen Friar's New Dictionary of Heraldry, a griffin's claw was believed to have medicinal properties and one of its feathers could restore sight to the blind.[1] Goblets fashioned from griffin claws (actually antelope horns) and griffin eggs (actually ostrich eggs) were highly prized in medieval European courts.[18]

When Genoa emerged as a major seafaring power in the Middle Ages and Renaissance, griffins commenced to be depicted as part of the republic's coat of arms, rearing at the sides of the shield bearing the Cross of St. George.

By the 12th century, the appearance of the griffin was substantially fixed: "All its bodily members are like a lion's, but its wings and mask are like an eagle's."[19] It is not yet clear if its forelimbs are those of an eagle or of a lion. Although the description implies the latter, the accompanying illustration is ambiguous. It was left to the heralds to clarify that.

A hippogriff is a legendary creature, supposedly the offspring of a griffin and a mare.

Heraldic significance

In heraldry, the griffin's amalgamation of lion and eagle gains in courage and boldness, and it is always drawn to powerful fierce monsters. It is used to denote strength and military courage and leadership. Griffins are portrayed with the rear body of a lion, an eagle's head with erect ears, a feathered breast, and the forelegs of an eagle, including claws. These features indicate a combination of intelligence and strength.[20]

In British heraldry, a male griffin is shown without wings, its body covered in tufts of formidable spikes, with a short tusk emerging from the forehead, as for a unicorn.[21] The female griffin with wings is more commonly used.

In architecture

In architectural decoration the griffin is usually represented as a four-footed beast with wings and the head of an eagle with horns, or with the head and beak of an eagle.[citation needed]

The statues that mark the entrance to the City of London are sometimes mistaken for griffins, but are in fact (Tudor) dragons, the supporters of the city's arms.[22] They are most easily distinguished from griffins by their membranous, rather than feathered, wings.

In literature

- For fictional characters named Griffin, see Griffin (surname)

Flavius Philostratus mentioned them in The Life of Apollonius of Tyana:

As to the gold which the griffins dig up, there are rocks which are spotted with drops of gold as with sparks, which this creature can quarry because of the strength of its beak. “For these animals do exist in India” he said, “and are held in veneration as being sacred to the Sun ; and the Indian artists, when they represent the Sun, yoke four of them abreast to draw the images ; and in size and strength they resemble lions, but having this advantage over them that they have wings, they will attack them, and they get the better of elephants and of dragons. But they have no great power of flying, not more than have birds of short flight; for they are not winged as is proper with birds, but the palms of their feet are webbed with red membranes, such that they are able to revolve them, and make a flight and fight in the air; and the tiger alone is beyond their powers of attack, because in swiftness it rivals the winds.[23]

And the griffins of the Indians and the ants of the Ethiopians, though they are dissimilar in form, yet, from what we hear, play similar parts; for in each country they are, according to the tales of poets, the guardians of gold, and devoted to the gold reefs of the two countries.[24]

Griffins are used widely in Persian poetry; Rumi is one such poet who writes in reference to griffins.[25]

In Dante Alighieri's Divine Comedy, after Dante and Virgil's journey through Hell and Purgatory has concluded, Dante meets a chariot dragged by a griffin in Earthly Paradise. Immediately afterwards, Dante is reunited with Beatrice. Dante and Beatrice then start their journey through Paradise.

Sir John Mandeville wrote about them in his 14th century book of travels:

In that country be many griffins, more plenty than in any other country. Some men say that they have the body upward as an eagle and beneath as a lion; and truly they say sooth, that they be of that shape. But one griffin hath the body more great and is more strong than eight lions, of such lions as be on this half, and more great and stronger than an hundred eagles such as we have amongst us. For one griffin there will bear, flying to his nest, a great horse, if he may find him at the point, or two oxen yoked together as they go at the plough. For he hath his talons so long and so large and great upon his feet, as though they were horns of great oxen or of bugles or of kine, so that men make cups of them to drink of. And of their ribs and of the pens of their wings, men make bows, full strong, to shoot with arrows and quarrels.[26]

John Milton, in Paradise Lost II, refers to the legend of the griffin in describing Satan:

As when a Gryfon through the Wilderness

With winged course ore Hill or moarie Dale,

Pursues the ARIMASPIAN, who by stelth

Had from his wakeful custody purloind

The guarded Gold [...]

Griffins appear in the fairy tales Jack the Giant Killer, The Griffin (fairy tale) and The Singing, Springing Lark.

In The Son of Neptune by Rick Riordan, Percy Jackson, Hazel Levesque, and Frank Zhang are attacked by griffins in Alaska.

In the Harry Potter series, the character Albus Dumbledore has a griffin-shaped knocker. Also, the character Godric Gryffindor's surname is a variation on the French griffon d'or ("golden griffon").

Pomponius Mela- "In Europe, constantly falling snow makes those places contiguous with the Riphean Mountains so impassable that, in addition, they prevent those who deliberately travel here from seeing anything. After that comes a region of very rich soil but quite uninhabitable because griffins, a savage and tenacious breed of wild beasts, love- to an amazing degree- the gold that is mined from deep within the earth there, and because they guard it with an amazing hostility to those who set foot there." (Romer, 1998.)

Isidore of Seville – "The Gryphes are so called because they are winged quadrupeds. This kind of wild beast is found in the Hyperborean Mountains. In every part of their body they are lions, and in wings and heads are like eagles, and they are fierce enemies of horses. Moreover they tear men to pieces." (Brehaut, 1912) [27]

Modern uses

The griffin is the symbol of the Philadelphia Museum of Art; bronze castings of them perch on each corner of the museum's roof, protecting its collection.[28][29] Similarly, prior to the mid-1990s a griffin formed part of the logo of Midland Bank (now HSBC).

The griffin is the logo of United Paper Mills, Vauxhall Motors, and of Scania and its former group partners SAAB-Aircraft and Saab Automobile. The latest fighter produced by the SAAB-Aircraft company bears the name of "Gripen" (Griffin), but as a result of public competition. During World War II, the Heinkel firm named its heavy bomber design for the Luftwaffe after the legendary animal, as the Heinkel He 177 Greif, the German form of "griffin". General Atomics has used the term "Griffin Eye" for its intelligence surveillance platform based on a Hawker Beechcraft King Air 35ER civilian aircraft[30]

The "Griff" statue by Veres Kalman 2007 in the forecourt of the Farkashegyi cemetery in Budapest, Hungary.

Griffins, like many other fictional creatures, frequently appear within works under the fantasy genre. Examples of fantasy-oriented franchises that feature griffins include Warhammer Fantasy Battle, Warcraft, Heroes of Might and Magic, the Griffon in Dungeons & Dragons, Ragnarok Online, Harry Potter, The Spiderwick Chronicles, My Little Pony: Friendship is Magic, and The Battle for Wesnoth.

-

The red griffin rampant was the coat of arms of the dukes of Pomerania and survives today as the armorial of West Pomeranian Voivodeship (historically, Farther Pomerania) in Poland.

-

Similarly, the coat of arms of Greifswald, Germany, in Mecklenburg-Vorpommern, also shows a red griffin rampant – perched in a tree, reflecting a legend about the town's founding in the 13th century.

-

Flag of the Utti Jaeger Regiment of the Finnish Army

-

Logo for the Saab Group

School emblems and mascots

This section needs additional citations for verification. (September 2017) |

Three gryphons form the crest of Trinity College, Oxford (founded 1555), originating from the family crest of founder Sir Thomas Pope. The college's debating society is known as The Gryphon, and the notes of its master emeritus show it to be one of the oldest debating institutions in the country, significantly older than the more famous Oxford Union Society.[31] Griffins are also mascots for VU University Amsterdam,[32] Reed College,[33] Sarah Lawrence College,[34] the University of Guelph, and Canisius College.[citation needed]

The official seal of Purdue University was adopted during the University's centennial in 1969. The seal, approved by the Board of Trustees, was designed by Prof. Al Gowan, formerly at Purdue. It replaced an unofficial one that had been in use for 73 years.[35]

The College of William and Mary in Virginia changed its mascot to the griffin in April 2010.[36][37] The griffin was chosen because it is the combination of the British lion and the American eagle.

The 367th Training Support Squadron's and 12th Combat Aviation Brigade feature griffins in their unit patches.

The emblem of the Greek 15th Infantry Division features an axe-wielding griffin on its unit patch.

The mascot of St Mary's College, one of the sixteen colleges in Durham University.

The mascot of Glenview Senior Public School in Toronto is the Gryphon, and the name is incorporated into its sporting teams.

The mascot of the L&N STEM Academy in Knoxville, Tennessee, a public science, technology, engineering and math high school serving grades 9-12, is the Gryphon. The school opening in August 2011. The Gryphon is also incorporated into the school's robotics team.

The mascot of Charles G. Fraser Junior Public School in Toronto is the Griffin, and an illustration of a griffin forms the school's logo.

The mascot of Glebe Collegiate Institute in Ottawa is the Gryphon, and the team name is the Glebe Gryphons.

The griffin is the official mascot of Chestnut Hill College and Gwynedd Mercy College, both in Pennsylvania.

Also Griffin is the Official mascot of Maria Clara High School, known as the Blue Griffins in PobCaRan cluster of Caloocan City Philippines, which excels in Cheerleading.

The mascot of Leadership High School in San Francisco, CA was chosen by the student body by popular vote to be the Griffin after the Golden Gate University Griffins, where they operated out of from 1997 to 2000.

Public organizations (non-educational)

A griffin appears in the official seal of the Municipality of Heraklion, Greece.

In professional sports

The Grand Rapids Griffins professional ice hockey team of the American Hockey League.

Suwon Samsung Bluewings's mascot "Aguileon" is Griffin. The name "Aguileon" is a compound using Spanish; "aguila" means "eagle", "leon" means "lion".

Amusement parks

Busch Gardens Williamsburg's highlight attraction is a dive coaster called "Griffon", which opened in 2007. In 2013, Cedar Point Amusement Park in Sandusky, Ohio opened the "GateKeeper" steel roller coaster which features a griffin as its mascot.

In film and television

Film and television company Merv Griffin Entertainment uses a griffin for its production company. Merv Griffin Entertainment was founded by entrepreneur Merv Griffin and is based in Beverly Hills, California. His former company Merv Griffin Enterprises also used a griffin for its logo.

Griffins appear in The Chronicles of Narnia: The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe, and The Chronicles of Narnia: Prince Caspian.

Use for real animals

Some large species of Old World vultures are called griffines, including the griffon vulture (Gyps fulvus). The scientific name for the Andean condor is Vultur gryphus, Latin for "griffin-vulture". The Catholic Douay-Rheims version of the Bible uses griffon for a creature referred to as vulture or ossifrage in other English translations (Leviticus 11:13).

Origin

A theory, postulated primarily by Adrienne Mayor, is that the griffin originated with ancient paleontological observations brought by long-distance traders to Europe along the Silk Road from the Gobi Desert in Mongolia, where white fossils of Protoceratops are naturally exposed against reddish ground. Such fossils, seen by ancient observers, may have been interpreted as evidence of a half-bird-half-beast.[38][39] Over repeated retelling and drawing recopying its bony neck frill (which is rather fragile and may have been frequently broken or entirely weathered away) may become large mammal-type external ears, and its beak may be treated as evidence of part-bird nature and lead to bird-type wings being added.[40]

However, the paleontologist Mark Witton has contested this hypothesis, as it relies on ignorance of pre-Greek griffin accounts and art, which have occurred considerably before the Central Asian trade scenario.[41]

See also

- Anzû (older reading: Zû), Mesopotamian monster

- Chimera, Greek mythological hybrid monster

- Duck billed platypus, an egg-producing mammal with a beak

- Hippogriff, legendary horse-eagle hybrid

- Hybrid creatures in mythology

- Lamassu, Assyrian deity, bull/lion-eagle-human hybrid

- List of hybrid creatures in mythology

- Nue, Japanese legendary creature

- Pegasus, winged stallion in Greek mythology

- Pixiu or Pi Yao, Chinese mythical creature

- Sharabha, Hindu mythology: lion-bird hybrid

- Simurgh, Iranian mythical flying creature

- Snow Lion, Tibetan mythological celestial animal

- Sphinx, mythical creature with lion's body and human head

- Yali, Hindu mythological lion-elephant-horse hybrid

- Ziz, giant griffin-like bird in Jewish mythology

Notes and references

- ^ a b c Friar, Stephen (1987). A New Dictionary of Heraldry. London: Alphabooks/A & C Black. p. 173. ISBN 0-906670-44-6.

- ^ Mayor, A. and Heaney, M. (1993). "Griffins and Arimaspeans". Folklore. 104 (1–2): 40. Retrieved 8 March 2017.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Adrienne Mayor, Archeology Magazine, November–December 1994, pp. 53–59; Mayor, The First Fossil Hunters, 2000.

- ^ Mark Witton, Why Protoceratops Almost Certainly Wasn't The Inspiration For Griffin Legend

- ^ von Volborth, Carl-Alexander (1981). Heraldry: Customs, Rules and Styles. Poole: New Orchard Editions. pp. 44–45. ISBN 1-85079-037-X.

- ^ William H. C. Propp,Exodus 19–40, volume 2A of The Anchor Bible, New York: Doubleday, 2006, ISBN 0-385-24693-5, Notes to Exodus 15:18, page 386, referencing: Julius Wellhausen, Prolegomena to the History of Israel, Edinburgh: Black, 1885, page 304. Also see: Robert S. P. Beekes, Etymological Dictionary of Greek, volume 1, Leiden and Boston: Brill, 2010 ISBN 978-90-04-17420-7, page 289, entry for γρυπος, "From the archaeological perspective, origin in Asia Minor (and the Near East: Elam) is very probable."

- ^ Illustrated Dictionary of Egyptian Mythology. Buffaloah.com. Retrieved on 2 January 2012.

- ^ The Gryphon Lore. www.myth-and-fantasy.com. Retrieved on 24 May 2014.

- ^ Strange (Fantastic) Animals of Ancient Egypt. Touregypt.net. Retrieved on 2 January 2012.

- ^ Patch, Diana (29 May 2012). Dawn of Egyptian Art. Metropolitan Museum of Art. pp. 139–140. ISBN 978-0300179521. Retrieved 24 May 2014.

- ^ Image of Persian griffin from The Granger Collection. www.granger.com. Retrieved on 26 May 2014.

- ^ Teissier, Beatrice (31 December 1996). Egyptian Iconography on Syro-Palestinian Cylinder Seals of the Middle Bronze Age. Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht. pp. 88–90. ISBN 978-3525538920. Retrieved 24 May 2014.

- ^ Aruz, Joan; Benzel, Kim; Evans, Jean M. (2008). Beyond Babylon: Art, Trade, and Diplomacy in the Second Millennium B.C. Metropolitan Museum of Art and Yale University Press. p. 137. ISBN 978-1588392954. Retrieved 24 May 2014.

- ^ Teissier, Beatrice (31 December 1996). Egyptian Iconography on Syro-Palestinian Cylinder Seals of the Middle Bronze Age. Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht. pp. 5–6. ISBN 978-3525538920. Retrieved 24 May 2014.

- ^ Neva, Elena. "Central Asian Jewelry and their Symbols in Ancient Time" Artwis; citing Pugachenkova, G. (1959) "Grifon v drevnem iskusstve central’noi Azii." Sovetskya Arheologia, 2 pp. 70, 83

- ^ Dartmouth College expedition

- ^ Quantara; Hoffman, 318

- ^ Bedingfeld, Henry; Gwynn-Jones, Peter (1993). Heraldry. Wigston: Magna Books. pp. 80–81. ISBN 1-85422-433-6.

- ^ White, T. H. (1992) [1954]. The Book of Beasts: Being a Translation From a Latin Bestiary of the Twelfth Century. Stroud: Alan Sutton. pp. 22–24. ISBN 0-7509-0206-X.

- ^ Stefan Oliver, Introduction to Heraldry. David & Charles, 2002. P. 44.

- ^ Male griffin depicted in Debrett's Peerage, 1968, p. 222, sinister supporter of Earl of Carrick (Ireland)

- ^ The City Arms, City of London Corporation, hosted by webarchive

- ^ Flavius Philostratus, The Life of Apollonius of Tyana, translated by F. C. Conybeare, volume I, book III.XLVIII., 1921, p. 333.

- ^ Flavius Philostratus, The Life of Apollonius of Tyana, translated by F. C. Conybeare, vol. II, book VI.I., 1921, p. 5.

- ^ The Essential Rumi, translated from Persian by Coleman Barks, p 257

- ^ The Travels of Sir John Mandeville, Chapter XXIX, Macmillan and Co. edition, 1900.

- ^ "Griffin".eaudrey.com., n.p., 14 March 2013 <http://www.eaudrey.com/myth/griffin.htm>

- ^ Philadelphia Museum of Art – Giving : Giving to the Museum : Specialty License Plates. Philamuseum.org. Retrieved on 2 January 2012.

- ^ Glassteelandstone.com Archived 11 May 2013 at the Wayback Machine, Philadelphia Museum of Art: Benjamin Franklin Parkway, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, United States, Glass Steel and Stone

- ^ GA-ASI Introduces Griffin Eye Manned ISR System. GA-ASI.com (20 July 2010). Retrieved on 2 January 2012.

- ^ Trinity.ox.ac.uk. Trinity.ox.ac.uk. Retrieved on 2 January 2012.

- ^ VU university Amsterdam. About the griffin. Retrieved on 5 November 2013.

- ^ Reed college#Griffin

- ^ Sarah Lawrence Gryphons. Gogryphons.com. Retrieved on 23 October 2013.

- ^ Traditions. Big Ten. Purdue.edu. Retrieved on 2 January 2012.

- ^ Pantless Man-Bird To Lead William and Mary Into Battle. Deadspin.com (7 April 2010). Retrieved on 2 January 2012.

- ^ W&M welcomes newest member of the Tribe. Wm.edu (8 April 2010). Retrieved on 2 January 2012.

- ^ Protoceratops. Wikidino. Retrieved on 2 January 2012.

- ^ BBC Four television program Dinosaurs, Myths and Monsters, 8.00–0.00 pm Sat 10 December 2011 and 9.55–10.55 pm Tue 13 December 2011

- ^ Mayor, A., & Heaney, M., 1993, "Griffins and Arimaspeans", Folklore 104(1-2): 40-66

- ^ Mark Witton, Why Protoceratops Almost Certainly Wasn't The Inspiration For Griffin Legend

Further reading

- Wild, F., Gryps-Greif-Gryphon (Griffon). Eine sprach-, kultur- und stoffgeschichtliche Studie (Wien, 1963) (Oesterreichische Akademie der Wissenschaften, Philologisch-historische Klasse, Sitzungberichte, 241).

- Bisi, Anna Maria, Il grifone: Storia di un motivo iconografico nell'antico Oriente mediterraneo (Rome: Università) 1965.

- Joe Nigg, The Book of Gryphons: A History of the Most Majestic of All Mythical Creatures (Cambridge, Apple-wood Books, 1982).

- This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Wood, James, ed. (1907). The Nuttall Encyclopædia. London and New York: Frederick Warne.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: Missing or empty|title=(help)

External links

- The Gryphon Pages, a repository of griffin lore and information

- The Medieval Bestiary: Griffin

- Four Footed Winged Raptors Gryphons of Greece, Europe and the Near East, source texts in Greek, Hebrew, and Old English, with new English translations.