The Day After Tomorrow

| The Day After Tomorrow | |

|---|---|

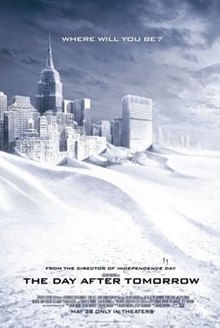

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Roland Emmerich |

| Screenplay by |

|

| Story by | Roland Emmerich |

| Based on | The Coming Global Superstorm by Art Bell and Whitley Strieber |

| Produced by |

|

| Starring | |

| Cinematography | Ueli Steiger |

| Edited by | David Brenner |

| Music by | Harald Kloser |

Production companies | |

| Distributed by | 20th Century Fox |

Release dates |

|

Running time | 123 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $125 million[1] |

| Box office | $552.6 million[1] |

The Day After Tomorrow is a 2004 American science fiction disaster film directed, co-produced, and co-written by Roland Emmerich. Based on the 1999 book The Coming Global Superstorm by Art Bell and Whitley Strieber, the film stars Dennis Quaid, Jake Gyllenhaal, Ian Holm, Emmy Rossum, and Sela Ward.

It depicts catastrophic climatic effects following the disruption of the North Atlantic Ocean circulation in a series of extreme weather events that usher in global cooling and lead to a new ice age.[2]

Originally slated for release in the summer of 2003, The Day After Tomorrow premiered in Mexico City on May 17, 2004 and was released in the United States on May 28, 2004. A major commercial success, the film became the sixth highest-grossing film of 2004. Filmed in Toronto and Montreal, it is the highest-grossing Hollywood film made in Canada (adjusted for inflation). It received mixed reviews upon release, with critics highly praising the film's special effects but criticizing its writing and numerous scientific inaccuracies.

Plot

Jack Hall, an American paleoclimatologist, and his colleagues Frank and Jason, drill for ice-core samples in the Larsen Ice Shelf for the NOAA, when the ice shelf suddenly begins to split away. At a UN conference in New Delhi, Jack discusses his research showing that climate change could cause an ice age, but US Vice President Raymond Becker dismisses his concerns. Professor Terry Rapson, an oceanographer of the Hedland Centre in Scotland, befriends Jack over his views of an inevitable climate shift. When several buoys in the Atlantic Ocean show a severe ocean temperature drop, Rapson concludes Jack's theories are correct. Jack's and Rapson's teams, along with NASA meteorologist Janet Tokada, build a forecast model based on Jack's research. Jack tries to get Becker to think about evacuations in the Northern States, but Becker again ignores him.

A massive storm system develops in the northern hemisphere, splitting into three gigantic hurricane-like superstorms above Canada, Scotland, and Siberia. The storms pull frozen air from the upper troposphere into their center, flash-freezing anything caught in their eyes with temperatures below −150 degrees Fahrenheit (−101 degrees Celsius). Meanwhile, the weather worsens across the world: Tokyo is struck by a giant hail storm, Nova Scotia has a 25-foot (8-meter) storm surge in seconds, a three-helicopter special task force tasked with rescuing the British Royal family from Balmoral Castle crashes in Scotland after all their fuel lines freeze, along with their crew, and Los Angeles is devastated by a tornado outbreak. Following this, President Blake issues an executive order for the FAA to ground all air traffic across the country, but not before several crash.

In New York City, Jack's son Sam, and his friends Brian Parks and Laura Chapman participate in an academic decathlon, where they meet a new friend JD. New York is soon caught in the North American storm and the weather becomes progressively more violent, resulting in street flooding, and eventually a massive tsunami-like storm surge inundating Manhattan. This forces Sam's group to seek shelter at the New York Public Library, but not before Laura accidentally cuts her leg. While cellphone communications are down, Sam is able to contact Jack and his mother Lucy, a physician, through a working payphone; Jack advises him to stay inside and promises to rescue him. Rapson and his team perish in the European storm, while Lucy remains in a hospital caring for bed-ridden children, where she and her patients are eventually rescued by the authorities.

Upon Jack's suggestion, Blake orders the southern states to be evacuated into Mexico; the northern half is doomed to be hit by the superstorm but are warned by the government to seek shelters and stay warm. The Mexicans initially close the border, but reopen it after Blake negotiates. With the storm having reached Washington, Blake perishes after his motorcade is caught in it, making Becker the new President. Jack, Jason, and Frank make their way to New York against all odds. In Pennsylvania, Frank falls through the skylight of a mall that had become covered in snow, and sacrifices himself by cutting his rope to prevent his friends from falling in after him. In the library, most survivors, as well as those from other structures, decide to head south once the floodwater outside freezes in spite of Sam's warnings, and are later found fatally frozen by Jack and Jason; only a few survivors end up heeding Sam's advice to stay put, burning books to stay warm as the temperatures plunge.

Laura develops blood poisoning from her injury, whereupon Sam, Brian, and JD scour a Russian cargo vessel that had drifted into the city for penicillin, fending off a pack of wolves which had escaped from Central Park Zoo. The eye of the North American storm arrives, freezing Manhattan solid, but Sam's group make it inside just in time. Likewise, Jack and Jason take shelter in an abandoned restaurant. Days later, the superstorms dissipate as Jack and Jason successfully reach the library, finding Sam's group alive. Jack then sends a radio message to US forces in Mexico.

Becker, in his first address as president from the US embassy in Mexico, apologizes on The Weather Channel for his ignorance, admits his mistake and sends helicopters to rescue survivors in the Northern States. Jack and Sam's group are picked up in Manhattan, where many people have survived. On the International Space Station, astronauts look down in awe at Earth's transformed surface, now with ice sheets extending across the northern hemisphere.

Cast

- Dennis Quaid as Jack Hall, a NOAA paleoclimatologist

- Jake Gyllenhaal as Samuel "Sam" Hall, Jack's son

- Sela Ward as Dr. Lucy Hall, a physician, Jack's wife and Sam's mother

- Emmy Rossum as Laura Chapman, Sam's friend and love interest

- Ian Holm as Terry Rapson, a Scottish oceanographer of Scotland's Hedland Centre

- Arjay Smith as Brian Parks, a high school student and Sam and Laura's friend

- Austin Nichols as J.D., a high school student of very wealthy parents who befriends Sam, Laura, and Brian

- Dash Mihok as Jason Evans, Jack's colleague

- Jay O. Sanders as Franklin "Frank" Harris, Jack's colleague

- Kenneth Welsh as Raymond Becker, US Vice President for the first half of the film, and President for the second half

- Perry King as Blake, US President, until death

- Nestor Serrano as Thomas "Tom" Gomez, a NOAA administrator

- Tamlyn Tomita as Janet Tokada, a NASA meteorologist

- Glenn Plummer as Luther, a homeless New Yorker with a dog named "Buddha".

- Adrian Lester as Simon, Rapson's colleague

- Richard McMillan as Dennis, Rapson's colleague

- Sasha Roiz as Parker, an ISS astronaut

- Christopher Britton as Vorsteen

- Amy Sloan as Elsa, a young woman trapped with Sam and the others in the New York Public Library

- Sheila McCarthy as Judith, a librarian at the New York Public Library

- Tom Rooney as Jeremy, who saves a C15 Gutenberg Bible from being burned in the library

- Christian Tessier as Aaron

- Mimi Kuzyk as Secretary of State

- Jason Blicker as Paul

- Ayana O'Shun as Jama

Production

The Day After Tomorrow was inspired by Coast to Coast AM talk-radio host Art Bell and Whitley Strieber's book, The Coming Global Superstorm,[3] and Strieber wrote the film's novelization. To choose a studio, writer Michael Wimer created an auction, with a copy of the script being sent to all major studios along with a term sheet. They had a 24-hour window to decide whether to produce the movie with Roland Emmerich directing, and Fox Studios was the only studio to accept the terms.[4]

The Day After Tomorrow was predominantly filmed in Montreal[5] and Toronto,[6] with some footage also shot in New York City[7] and Chiyoda, Tokyo.[8] Filming ran from November 7, 2002, until October 18, 2003.[9]

The Day After Tomorrow features 416 visual effects shots, with nine effects houses, notably Industrial Light & Magic and Digital Domain, and over 1,000 artists working on the film for over a year.[10] Although a miniature set was initially considered according to the behind-the-scenes documentary, for the destruction of New York sequence effects artists instead utilized a 13 block-sized 3D model of Manhattan which was then textured with over 50,000 scanned photographs;[11] due to its overall complexity and a tight schedule, the storm surge scene required as many as three special effects vendors for certain shots.[12] Similarly, the opening flyover of Antarctica was entirely computer-generated—it is considered to be the longest all-CG opening scene in film history, surpassing the space zoom-out from the opening of Contact (1997).[13]

Music

The score soundtrack for the film was composed by Harald Kloser and released by Varèse Sarabande.[14]

Reception

Box office

The film ranked No. 2 at the box office (behind Shrek 2) over its four-day Memorial Day opening, grossing $85,807,341. It led the per-theater average, with a four-day average of $25,053 (compared to Shrek 2's four-day average of $22,633). At the end of its theatrical run, the film grossed $186,740,799 domestically and $544,272,402 worldwide. It was the second-highest opening-weekend film not to lead at the box office; Inside Out surpassed it in June 2015.[1]

Critical response

Review aggregator Rotten Tomatoes reports that 45% of 220 critics reviewed the film positively, with an average rating of 5.29/10. According to the website, it is "a ludicrous popcorn flick filled with clunky dialogues, but spectacular visuals save it from being a total disaster."[15] Roger Ebert of the Chicago Sun-Times described the film as "profoundly silly" but nonetheless said the film was effective and praised the special effects. He gave it three stars out of four.[16]

Accolades

| Award | Subject | Nominee | Result |

|---|---|---|---|

| Saturn Awards | Best Science Fiction Film | Nominated | |

| Best Special Effects | Karen E. Goulekas, Neil Corbould, Greg Strause and Remo Balcells | Nominated | |

| BAFTA Awards | Best Visual Effects | Won | |

| VES Awards | Outstanding Visual Effects in an Effects Driven Motion Picture | Karen Goulekas, Mike Chambers, Greg Strause, Remo Balcells | Nominated |

| Best Single Visual Effect | Karen Goulekas, Mike Chambers, Chris Horvath, Matthew Butler | Won | |

| MTV Movie Awards | Best Action Sequence | "The destruction of Los Angeles" | Won |

| Best Breakthrough Performance | Emmy Rossum | Nominated | |

| Irish Film & Television Awards | Best International Actor | Jake Gyllenhaal | Nominated |

| Golden Trailer Awards | Best Action Film | Nominated | |

| Environmental Media Awards | Best Film | Won | |

| BMI Film Awards | Best Music | Harald Kloser | Won |

| Golden Reel Awards | Best Sound Editing – Effects & Foley | Mark P. Stoeckinger, Larry Kemp, Glenn T. Morgan, Alan Rankin, Michael Kamper, Ann Scibelli, Randy Kelley, Harry Cohen, Bob Beher and Craig S. Jaeger | Nominated |

Political and scientific criticism

Emmerich did not deny that his casting of a weak president and the resemblance of vice-president Kenneth Welsh to Dick Cheney were intended to criticize the climate change policy of the George W. Bush administration.[17] Responding to claims of insensitivity in his inclusion of scenes of a devastated New York City less than three years after the September 11 attacks, Emmerich said that it was necessary to showcase the increased unity of people in the face of disaster because of the attacks.[18][19][20]

Some scientists criticized the film's scientific aspects. Paleoclimatologist and professor of earth and planetary science at Harvard University Daniel P. Schrag said, "On the one hand, I'm glad that there's a big-budget movie about something as critical as climate change. On the other, I'm concerned that people will see these over-the-top effects and think the whole thing is a joke ... We are indeed experimenting with the Earth in a way that hasn't been done for millions of years. But you're not going to see another ice age – at least not like that."[17] J. Marshall Shepherd, a research meteorologist at the NASA Goddard Space Flight Center, expressed a similar sentiment: "I'm heartened that there's a movie addressing real climate issues. But as for the science of the movie, I'd give it a D minus or an F. And I'd be concerned if the movie was made to advance a political agenda."[17] According to University of Victoria climatologist Andrew Weaver, "It's The Towering Inferno of climate science movies, but I'm not losing any sleep over a new ice age, because it's impossible."[17]

Patrick J. Michaels, a largely oil-funded climate change denier[21] and former research professor of environmental science at the University of Virginia who rejects the scientific consensus[22] on global warming, called the film "propaganda" in a USA Today editorial: "As a scientist, I bristle when lies dressed up as 'science' are used to influence political discourse."[23] College instructor and retired NASA Office of Inspector General senior special agent Joseph Gutheinz called The Day After Tomorrow "a cheap thrill ride, which many weak-minded people will jump on and stay on for the rest of their lives" in a Space Daily editorial.[24]

Stefan Rahmstorf of the Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research, an expert on thermohaline circulation and its effect on climate, said after a talk with scriptwriter Jeffrey Nachmanoff at the film's Berlin preview:

Clearly this is a disaster movie and not a scientific documentary, [and] the film makers have taken a lot of artistic license. But the film presents an opportunity to explain that some of the basic background is right: humans are indeed increasingly changing the climate and this is quite a dangerous experiment, including some risk of abrupt and unforeseen changes ... Luckily it is extremely unlikely that we will see major ocean circulation changes in the next couple of decades (I'd be just as surprised as Jack Hall if they did occur); at least most scientists think this will only become a more serious risk towards the end of the century. And the consequences would certainly not be as dramatic as the 'superstorm' depicted in the movie. Nevertheless, a major change in ocean circulation is a risk with serious and partly unpredictable consequences, which we should avoid. And even without events like ocean circulation changes, climate change is serious enough to demand decisive action.[25]

Environmental activist and Guardian columnist George Monbiot called The Day After Tomorrow "a great movie and lousy science".[26]

In 2008, Yahoo! Movies listed The Day After Tomorrow as one of its top-10 scientifically inaccurate films.[27] It was criticized for depicting meteorological phenomena as occurring over the course of hours, instead of decades or centuries.[28] A 2015 Washington Post article reported on a paper published in Scientific Reports which indicated that global temperatures could drop relatively rapidly (one degree Fahrenheit change or 0.5 degrees Celsius change over an 11-year period) due to a temporary shutdown of the Atlantic meridional overturning circulation caused by global warming.[29]

Home media

The film was released on VHS and DVD by 20th Century Fox Home Entertainment on October 12, 2004, and was released in high-definition video on Blu-ray in North America on October 2, 2007, and in the United Kingdom on April 28, 2008, in 1080p with a lossless DTS-HD Master Audio track and few bonus features. DVD sales were $110 million, bringing the film's gross to $652,771,772.[30]

See also

- Six Degrees: Our Future on a Hotter Planet – a 2007 non-fiction book

- The Coming Global Superstorm – a book on which the movie is based

- Fifty Degrees Below – a Kim Stanley Robinson novel in which greenhouse warming similarly disrupts the Gulf Stream

- Time of the Great Freeze – a novel by Robert Silverberg about a second Ice Age

- The World in Winter – a 1962 book by John Christopher about the beginning of a new ice age

- Geostorm – a 2017 film with disasters taking place around the world

- Ice – a 1998 film with a similar premise starring Grant Show, Udo Kier, and Eva La Rue

- Survival film

References

- ^ a b c "The Day After Tomorrow (2004)". Box Office Mojo. Retrieved April 16, 2011.

- ^ Gillis, Justin (March 22, 2016). "Scientists Warn of Perilous Climate Shift Within Decades, Not Centuries". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved March 22, 2016.

- ^ Emmerich, Roland; Gordon, Mark. "Day After Tomorrow Q&A with Roland Emmerich and Mark Gordon". Phase9 Entertainment. Retrieved November 17, 2017.

- ^ Russell, Jamie (April 19, 2012). "Why the Halo Movie Failed to Launch". WIRED. Conde Nast. Retrieved February 9, 2017.

- ^ Rocha, Robert (October 19, 2019). "Here's what we learned from 20 years of film shoots in Montreal". CBC.ca. Retrieved October 24, 2020.

- ^ Rocha, Robert (September 18, 2017). "Canadian Hot Spots You May Not Realise Were In Your Favourite Movies". Huffington Post. Retrieved October 24, 2020.

- ^ "The Day After Tomorrow (2004)". Onthesetofnewyork.com/. Retrieved October 24, 2020.

- ^ "15 Famous Movies Filmed in Tokyo (Japan)". The Irishman.com. February 18, 2018. Retrieved October 24, 2020.

- ^ "Ciekawostki - Pojutrze (2004)". Filmweb (in Polish). Retrieved May 28, 2021.

- ^ "Story Notes for The Day After Tomorrow". AMC. July 2014. Retrieved August 7, 2017.

- ^ Dirks, Tim. "Visual and Special Effects Film Milestones". AMC filmsite. Retrieved January 17, 2018.

- ^ Restuccio, Daniel (June 1, 2004). "THE DAY AFTER TOMORROW'S PHOTOREAL EFFECTS". Post Magazine. Retrieved January 19, 2018.

- ^ Dirks, Tim. "Visual and Special Effects Film Milestones". AMC filmsite. Retrieved May 28, 2021.

- ^ "The Day After Tomorrow (Original Motion Picture Soundtrack)". AllMusic. Retrieved April 13, 2020.

- ^ "The Day After Tomorrow". Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved April 18, 2021.

- ^ Ebert, Roger. "The Day After Tomorrow Movie Review (2004)". Chicago Sun-Times. Retrieved August 7, 2017 – via Roger Ebert.

- ^ a b c d Bowles, Scott (May 26, 2004). "'The Day After Tomorrow' heats up a political debate Storm of opinion rains down on merits of disaster movie". USA Today. Retrieved January 12, 2009.

- ^ Gilchrist, Todd (May 2004). "The Day After Tomorrow: An Interview with Roland Emmerich". BlackFilm.com. Retrieved March 16, 2009.

- ^ Robert Epstein, Daniel. "Roland Emmerich of The Day After Tomorrow (20th Century Fox) Interview". UGO.com. Archived from the original on June 13, 2004. Retrieved March 16, 2009.

- ^ Chau, Thomas (May 27, 2004). "INTERVIEW: Director Roland Emmerich on "The Day After Tomorrow"". Cinema Confidential. Archived from the original on June 6, 2004. Retrieved March 16, 2009.

- ^ "Patrick J. Michaels – SourceWatch". www.sourcewatch.org.

- ^ "Scientific consensus: Earth's climate is warming". Climate Change: Vital Signs of the Planet. Retrieved January 31, 2017.

- ^ Michaels, Patrick J. (May 25, 2014). "'Day After Tomorrow': A lot of hot air". USA Today. Retrieved April 16, 2011.

- ^ Richard Gutheniz Jr., Joseph (May 27, 2004). "There Will Be A Day After Tomorrow". Space Daily. Retrieved April 16, 2011.

- ^ Rahmstorf, Stefan. "The Day After Tomorrow—Some comments on the movie". Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research. Archived from the original on October 11, 2004. Retrieved August 7, 2016.

- ^ Monbiot, George (May 14, 2004). "A hard rain's a-gonna fall". The Guardian. Retrieved April 16, 2011.

- ^ "Top 10: Scientifically Inaccurate Movies". Yahoo7 Movies. Wayback Machine. July 28, 2008. Archived from the original on April 2, 2015. Retrieved August 7, 2017.

- ^ "Disaster Flick Exaggerates Speed Of Ice Age". Science Daily. May 13, 2004. Retrieved April 16, 2011.

- ^ Wang, Yanan (October 12, 2015). "Model suggests possibility of a 'Little Ice Age'". Washington Post. Retrieved August 7, 2016.

- ^ "DVD Sales Chart – 2004 Full Year". Lee's Movie Info. Retrieved April 16, 2011.

External links

- 2004 films

- 20th Century Fox films

- 2000s disaster films

- 2004 science fiction action films

- 2000s action thriller films

- American disaster films

- American films

- American science fiction action films

- American science fiction thriller films

- Centropolis Entertainment films

- Climate change films

- 2000s English-language films

- Environmental films

- Films about fictional presidents of the United States

- Films about tornadoes

- Films about tsunamis

- Films directed by Roland Emmerich

- Films scored by Harald Kloser

- Films set in 2004

- Films set in libraries

- Films set in Antarctica

- Films set in Delhi

- Films set in Los Angeles

- Films set in Mexico

- Films set in New York City

- Films set in Scotland

- Films set in the White House

- Films set in Tokyo

- Films set in Washington, D.C.

- Films shot in Tokyo

- Films shot in Montreal

- Films shot in New York City

- Films shot in Toronto

- Flood films

- Lionsgate films

- Apocalyptic films

- United States presidential succession in fiction

- BAFTA winners (films)

- Films based on non-fiction books