Hispanics and Latinos in San Diego

This article may incorporate text from a large language model. (May 2024) |

Hispanic and Latino Americans make up 30.1% (pop. 400,337) of the population of the City of San Diego, California in the US, and 35.0% (pop. 1,145,183) of the County of San Diego,[1][2] with the majority of Hispanics and Latinos in San Diego being Mexican American.

Origin breakdown

| Hispanic/Latino Origin/Ancestry | City of San Diego | County of San Diego |

|---|---|---|

| 331,283 | 984,171 | |

| 12,228 | 27,587 | |

| 9,307 (2016)[3] | 19,717 | |

| 5,620 | 14,774 | |

| 6,756 | 12,210 | |

| 8,119 | 11,945 | |

| 4,785 | 11,572 | |

| 3,284 | 10,251 | |

| 3,091 (2010)[4] | ||

| 2,860 | 7,581 | |

| 2,097 | 3,859 | |

| 1,158 | 3,665 | |

| 1,233 | 4,518 | |

| 1,544 | 2,361 |

History

The region has been shaped by the presence and contributions of Hispanics and Latinos ever since the discovery of San Diego by Juan Rodríguez Cabrillo in 1542.

Spanish colonization

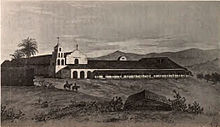

The Spanish established a presidio (fort) and Mission San Diego de Alcalá in 1769, marking the foundation of the city.[5] Over the following decades, more missions were established throughout California, including the nearby Mission San Luis Rey de Francia. During the Spanish colonial period, which lasted until 1821, the region became an important location for trade and communication.

Mexican/Californio Rancho period

With Mexico's independence from Spain in 1821, San Diego became part of Mexican territory. The period of Mexican rule saw the growth of a vibrant Mexican population in San Diego. The Californio rancheros, descendants of Spanish settlers, played a significant role in the development of the region. They engaged in ranching, agriculture, and trade, contributing to the economic prosperity of San Diego. Prominent Californio families and individuals, such as the Estudillos and Peruvian-born Juan Bandini, played a crucial role in shaping the city's development and cultural identity.[6]

After the Mexican-American War

In 1848, the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo ended the Mexican-American War, and San Diego, along with the rest of California, became part of the United States. This transition marked a pivotal point in the history of Hispanics and Latinos in San Diego, as their status and rights within the new American society were redefined.

Californios secured cultural and social recognition in the region, but were unable to control the political system. By 1860, most had left the area and the remainder were on the decline economically.[7] Many Mexican Americans in San Diego left for Tijuana and other parts of Baja California, those who stayed faced various challenges during this period. Discrimination and political marginalization were prevalent, undermining their social and economic opportunities.[8]

As San Diego grew in the early 1900's, the region also attracted Portuguese immigrants, with many of them settling in the Roseville-Fleetridge neighborhood in Point Loma, San Diego, with many employed in the city's tuna industry.[9]

In World War II, Hispanics made major breakthroughs in employment San Diego and in nearby farm districts. They benefitted from new skills, contacts, and experiences provided by the military, filled many newly opened unskilled labor jobs, gained some high-paying jobs in the military installations and aircraft factories, and were welcomed by the labor unions, especially the Cannery Workers Union.

The civil rights movement in the United States had a profound impact on the Hispanic and Latino community in San Diego. Activists and organizations, such as the Chicano Movement, fought for equal rights, educational opportunities, and improved living conditions. Their efforts paved the way for greater inclusion and recognition of the contributions made by Hispanics and Latinos in San Diego.

Communities

Barrio Logan

Barrio Logan, located in the southeastern part of downtown San Diego, is a historically significant neighborhood predominantly inhabited by Mexican Americans. The community has deep roots tracing back to the early 20th century when Mexican laborers settled in the area, working in the nearby shipyards and canneries. Despite facing economic challenges and social injustices, the residents of Barrio Logan have demonstrated resilience and pride in their heritage.[10]

Today, Barrio Logan is recognized as an important cultural hub and is renowned for its vibrant Chicano art scene. The neighborhood is home to numerous art galleries, studios, and mural-lined streets that showcase the creativity and activism of the local community. The Chicano Park, established in 1970 beneath the San Diego-Coronado Bridge, stands as a symbol of cultural pride and activism, adorned with colorful murals depicting Mexican and Chicano history and culture.[11]

Logan Heights

Logan Heights, located just east of downtown San Diego, has a significant history and presence of Mexican American and Latino residents. It was established in the late 19th century as a residential area for workers in the booming industries of the time.

The neighborhood has been the site of significant civil rights struggles and community activism. During the 1960s and 1970s, Logan Heights was at the forefront of the Chicano Movement, advocating for social justice, educational equity, and fair representation. The community successfully fought against the displacement of residents due to urban renewal projects, preserving the neighborhood's cultural heritage.[12]

City Heights

City Heights, located in the eastern part of San Diego, is a diverse neighborhood that reflects the multicultural tapestry of the city. It has a significant population of immigrants from Central America, South America, and other Hispanic Caribbean countries. Over the years, City Heights has been a destination for refugees and immigrants fleeing political unrest, violence, and economic hardships in their home countries.

San Ysidro

San Ysidro, located in the southernmost part of San Diego, on the U.S.-Mexico border, is a vibrant community with a significant Hispanic and Latino population. It serves as a gateway between the United States and Mexico, characterized by its cultural diversity and strong ties to Mexican heritage.

San Ysidro has a rich history shaped by its proximity to Mexico and its role as a busy land border crossing. The community embraces its cross-border connections, with many residents having familial and cultural ties on both sides of the border. The neighborhood's cultural heritage is reflected in its diverse mix of Mexican, Central American, and other Hispanic and Latino populations.

Avenida de Portugal (Little Portugal - Roseville-Fleetridge)

The Roseville-Fleetridge neighborhood of San Diego holds the main street for Portuguese community and business known as Avenida de Portugal, the city's unrecognized Little Portugal district. Saint Agnes Catholic Church holds services in Portuguese twice a month and hosts the annual Festa do Espirito Santo (Feast of the Holy Spirit), a religious festival which has been staged every year since 1910 and is San Diego's oldest ethnic tradition.[13] Many Portuguese San Diegans can trace their origins to the Azores and Madeira. Community members of the area have been seeking an official recognition for a Little Portugal district.[14]

Culture

San Diego's Hispanic and Latino culture has deeply influenced its architecture, cuisine, and art. These cultural elements reflect the diverse heritage and traditions of the Hispanic and Latino communities in the region.

Architecture

The Mission Revival architecture, prevalent in San Diego, pays homage to the Spanish colonial heritage. Inspired by the design of the California missions, this architectural style features elements such as red tile roofs, stucco walls, bell towers, and arched windows and doorways. Notable examples of Mission Revival architecture in San Diego include the Santa Fe Depot and the Junípero Serra Museum, and can be found in the construction of schools, libraries, churches, and commercial structures.[15]

Spanish Colonial Revival architecture, prevalent in the early 20th century, draws influence from the Spanish colonization period. Buildings designed in this style feature elements such as white stucco walls, wrought iron details, courtyards, and tilework. Balboa Park, home to numerous Spanish Colonial Revival buildings, including the California Building and the San Diego Museum of Us, showcases the grandeur of this architectural style.[16]

Cuisine

San Diego's culinary scene is known for its diverse Hispanic and Latino influences, with several dishes becoming some of the representations of the local food culture.

Fish Tacos

Fish Tacos, a staple of San Diego's cuisine, originated from Baja California but was first popularized by the Rubio's fast-food chain in San Diego. This dish consists of fresh fish, typically battered and fried, served in a soft tortilla with cabbage, salsa, and a squeeze of lime.

Carne Asada Fries

Carne Asada Fries, a San Diego creation, have also become a popular indulgence. While the exact origin of this dish is debated, Lolita's Mexican Food, a restaurant in San Diego, claims to have originated it in the late 1990s.[17] Carne Asada Fries feature French fries topped with marinated and grilled carne asada, melted cheese, guacamole, sour cream, and salsa.

California Burrito

Another San Diego invention is the California Burrito. This burrito typically includes a flour tortilla filled with carne asada, French fries, cheese, sour cream, and salsa.

Restaurant franchises

The city is also home to various food chains, such as Roberto's Taco Shop (founded in 1964) and Rubio's Coastal Grill (founded in 1963), which have played significant roles in popularizing Mexican cuisine in the region.

Arts

Chicano Park, located beneath the San Diego-Coronado Bridge in Barrio Logan, stands as a vibrant outdoor gallery and symbol of cultural pride. The park is adorned with murals that depict Mexican and Chicano history, culture, and struggles. [11]

Balboa Park

The Spanish Village Art Center, situated in Balboa Park, was constructed with the intent of emulating a Spanish village. The center features studios, galleries, and shops where visitors can witness and purchase a wide range of artistic works, including paintings, ceramics, and sculptures.

Centro Cultural de la Raza, located in Balboa Park, is a cultural center dedicated to promoting and preserving Mexican, Chicano, and indigenous arts and culture. It hosts exhibitions, performances, workshops, and community events that celebrate the heritage and contributions of the Hispanic and Latino communities in San Diego.

Film

The San Diego Latino Film Festival began in 1993 and focuses on diverse groups and culture in the Latino community through films.[18][19]

Notable San Diegans of Hispanic or Latino origin

- Juan Bandini, Peruvian-Californio Ranchero and Politician

- Ricardo Breceda, Mexican-American Sculptor

- Dominick Cruz, mixed martial artist, former UFC bantamweight champion of Mexican descent

- Luca de la Torre, Spanish-American professional soccer player

- Cameron Diaz, actress (My Best Friend's Wedding, Charlie's Angels)

- José Guadalupe Estudillo, Californio California State Treasurer

- Gabriel Iglesias, Mexican-American stand-up comedian

- Father Luís Jayme, Spanish-born Roman Catholic priest, California's first Catholic martyr

- Mario López, Mexican-American actor and television personality (Saved by the Bell, Extra!) from Chula Vista

- Dominik Mysterio, professional wrestler, son of Rey Mysterio father son tag team champions

- El Hijo de Rey Misterio, professional wrestler

- Rey Mysterio, professional wrestler, WWE Grand Slam Champion first ever father son tag team champions

- Ellen Ochoa, Mexican-American NASA Astronaut

- Sara Ramirez, Mexican American Tony-winning actress and singer

- Lil Rob, Chicano rapper from Solana Beach

- Jessica Sanchez, Mexican-American American Idol contestant

- Roberto Tapia, Mexican-American musician

- Victor Villaseñor, Mexican-American author from Carlsbad

References

- ^ "U.S. Census Bureau QuickFacts: San Diego city, California". www.census.gov. Retrieved 2023-07-09.

- ^ "U.S. Census Bureau QuickFacts: San Diego County, California". www.census.gov. Retrieved 2023-07-09.

- ^ "2016 American Community Survey Selected Population Tables". American FactFinder. U.S. Census Bureau. Archived from the original on February 14, 2020. Retrieved March 2, 2018.

- ^ Hawkins, Robert J. (2010-09-13). "Local Brazilians turn P.B. into Rio". San Diego Union-Tribune. Retrieved 2023-11-06.

- ^ Leffingwell, Randy (2005), California Missions and Presidios: The History & Beauty of the Spanish Missions. Voyageur Press, Inc., Stillwater, MN. ISBN 0-89658-492-5, p. 17

- ^ Bell, Diane (2018-12-04). "Column: Furnishing an Old Town adobe that tells San Diego's story was a labor of love and perseverance". San Diego Union-Tribune. Retrieved 2023-07-09.

- ^ Mario T. García, "The Californios of San Diego and the Politics of Accommodation 1846-1860," Aztlan (1975) 6#1 pp 69-85

- ^ "A Chicano Perspective on San Diego History". San Diego History Center | San Diego, CA | Our City, Our Story. Retrieved 2023-07-09.

- ^ San Diego Union Tribune, May 31, 2009, via Wayback Machine.

- ^ "Community Profiles Barrio Logan | City of San Diego Official Website". Sandiego.gov. Retrieved 2016-11-12.

- ^ a b "Chicano Park: National Landmark, Local Treasure". www.sandiego.org. Retrieved 2023-07-09.

- ^ "Chicano Park - Brief History of the Takeover". www.chicano-park.com. Retrieved 2023-07-09.

- ^ Monteagudo, Merrie (2022-06-10). "From the Archives: Point Loma's Portuguese chapel was built in 1922 to hold the Crown of the Holy Spirit". San Diego Union-Tribune. Retrieved 2023-11-07.

- ^ "Little Portugal – United Portuguese S.E.S." Retrieved 2023-11-07.

- ^ Starr, Raymond. "California's Mission Revival". San Diego History Center | San Diego, CA | Our City, Our Story. Retrieved 2023-07-09.

- ^ "Style 101: Spanish Colonial Revival | IS Architecture". 2017-02-10. Retrieved 2023-07-09.

- ^ Blumberg, Nick (27 June 2014). "Carne Asada Fries, The Can't-Miss Mexican-American Fast Food". KJZZ. Phoenix, Arizona. Retrieved 28 May 2015.

- ^ Baxter, Kevin (1998-10-01). "Cinema Espanol". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 2023-12-15.

- ^ Hanna, Gigi (2000-03-06). "Latino Film Festival to come". North County Times. p. 9. Retrieved 2023-12-15 – via Newspapers.com.