Invasion of Poland

| World War II | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| German soldiers destroying Polish border checkpoint on 1st September. Second World War begins. German troops destroying a Polish border checkpoint, September 1, 1939. World War II begins. | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Poland | Germany and allies, Soviet Union | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Edward Rydz-Śmigły |

Fedor von Bock (Army Group North) Gerd von Rundstedt (Army Group South) | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

39 divisions, 16 brigades 1 million soldiers 4,300 guns 880 tanks 435 aircraft |

56 divisions, 4 brigades 1,8 million soldiers 10,000 guns 2,800 tanks 3,000 aircraft | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

65 000 killed1 133 700 wounded 694 000 POWs |

16 343 killed 27 280 wounded 320 MIA | ||||||

The Polish September Campaign or Defensive War of 1939 (Polish: Wojna obronna 1939 roku) was the conquest of Poland by the armies of Nazi Germany, the Soviet Union, and a small contingent of Slovak forces during the Second World War. The campaign began on 1 September 1939 and ended on 6 October 1939, with Germany and the Soviet Union occupying the entirety of Poland. Neither side - Germany, Western Allies or the Soviet Union - expected that this German invasion of Poland would lead to the war that would surpass the First World War in its scale and cost. This military operation marked the start of the Second World War in Europe, as the invasion led Poland's allies the United Kingdom and France to declare war on Germany on September 3. It was also the first campaign to witness the use of German Blitzkrieg tactics.

Following the German-staged attack on September 1, 1939, German forces invaded Poland's western, southern and northern borders. Polish armies, defending the long borders, were soon forced to withdraw east. After the mid-September Polish defeat in the Battle of Bzura, Germans gained undisputed initiative. Polish forces then begun a withdrawal south-east, following a plan that called for long defence in the Romanian bridgehead area, where the Polish forces were to await expected Western Allies counterattack and relief. On September 17, 1939, the Soviet Red Army invaded the eastern regions of Poland. The Soviets were acting in co-operation with Nazi Germany, carrying out their part of the secret appendix of the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact (the division of Europe into Nazi and Soviet spheres of influences). In view of the unexpected Soviet agression, Polish government and high command decided that the defence of the Romanian bridgehead was no longer feasible and ordered the evacuation of all troops to neutral Romania. By the begining of October, Poland's territory was completely overrun by Germany and the Soviet Union. The Polish government, which never surrendered, together with its many of its remaining land and air forces, successfully evacuated to neighboring Romania and Hungary. Many of the evacuees subsequently joined the recreated Polish army in allied France, French-mandated Syria and the United Kingdom.

In the aftermath of the September Campaign, Poland, even under occupation, managed to create a powerful resistance movement and to contribute significant military forces to the Allies for the entire duration of World War II. The Soviet-occupied areas would later be captured by Germany when she invaded the Soviet Union (June 22, 1941), and recaptured again by the Soviet Union in 1944. Both the German and Soviet occupations were responsible for the death over 20% of Polish's citizens and meant the effective end of the Second Polish Republic.

Names of the campaign

The campaign is known by several names. The German operational plan was codenamed Fall Weiß (Fall Weiss — "Plan White"). From the German perspective the war is called the "the September Campaign." Polish historians also term it Wojna obronna 1939 roku ("the Defensive War of 1939"). Other names include "Polish-German War of 1939" and "Polish Campaign."

Prelude to the campaign

In 1933 the Nazi Party led by Adolf Hitler took power in Germany. Hitler at first ostentatiously pursued a policy of rapprochement with Poland, culminating in the Polish-German Non-Aggression Pact of 1934. But following Germany's annexation of Austria in 1938 and most of Czechoslovakia in 1939 and the contined Allied policy of appeasement, the Nazi regime turned its attention to Poland. Of special concern to Germany was the little known territory called the Polish Corridor. This was a narrow strip of land separating East Prussia from main Germany and allowing access for Poland to the Baltic Sea. This small strip of territory was a continual annoyance for the Germans. In early 1939, Hitler issues orders to prepare for the "solution of the Polish problem by military means" and the German government intensified demands for the annexation of Free City of Danzig, as well as for construction of an extra-territorial road through the Polish Corridor, connecting East Prussia with the rest of Germany. Fall Weiss plan was be ready by April 3.

Hitler and most of his advisors expected Polish government to yield to those demands, as many other governments have done before. However the Polish government rejected these demands, and were backed on March 30 by guarantees from Britain and France, now concerned at German expansionism. The government of the United Kingdom pledged to defend Poland, in the event of a German attack, and Romania in case of other threats. However, the British “guarantee” of Poland was not complete, and it adressed only of Polish independence, and pointly excluded Polish territorial integrity. This further encouraged Hitler, who believed that Britain and France would be unwilling to take any military action. On April 28 Germany withdraws from both the Polish-German Non-Aggression Pact of 1934 and the London Naval Agreement of 1935.

The basic goal of British foreign policy between 1919-1939 was to prevent another world war by a mixture of “carrot and stick”. The “stick” in this case was the “guarantee” of March 1939, which was intended to prevent Germany from attacking either Poland or Rumania. At the same time, the Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain and his Foreign Secretary Lord Halifax hoped to offer a “carrot” to Hitler in the form of another Munich type deal that would see the Free City of Danzig and the Polish Corridor returned to Germany in exchange for a promise by Hitler to leave the rest of Poland alone.

This declaration was further amended in April, when Poland's minister of foreign affairs Colonel Józef Beck met with Neville Chamberlain and Lord Halifax. In the aftermath of the talks a mutual assistance treaty was signed. On August 25 the Polish-British Common Defence Pact was signed as an annex to Polish-French alliance. Like the “guarantee” of March 30, the Anglo-Polish alliance committed Britain only to the defence of Polish independence. It was clearly aimed against German aggression. In case of war United Kingdom was to start hostilities as soon as possible; initially helping Poland with air raids against the German war industry, and joining the struggle on land as soon as the British Expeditionary Corps arrives to France. In addition, a military credit was granted and armament was to reach Polish or Romanian ports in early autumn.

However, both British and French governments had other plans than fulfilling the treaties with Poland. On May 4, 1939, a meeting was held in Paris, at which it was decided that the fate of Poland depends on the final outcome of the war, which will depend on our ability to defeat Germany rather than to aid Poland at the beginning. Poland's government was not notified of this decision, and the Polish–British talks in London were continued. Also in May 1939, Poland signed a secret protocol to the Franco-Polish Military Alliance (signed in 1921), in which was agreed that France would grant her eastern ally a military credit as soon as possible. In case of war with Germany, France promised to start minor land and air military operations at once, and to start a major offensive (with the majority of its forces) not later than 15 days after the declaration of war. A full military alliance treaty between Poland and Great Britain was ready to be signed on August 22, but His Majesty's government postponed the signing until August 25, 1939.

At the same time secret German-Soviet talks were held in Moscow which resulted in signing of the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact on August 22. Hitler intended to neutralize the possibility that the Soviet Union would resist the invasion of its western neighbour. In a secret protocol of this pact, the Germans and the Soviets agreed that Poland should be divided between them, with the western third of the country going to Germany and the eastern two-thirds being taken over by the USSR.

The German assault was originally scheduled to begin on 0400 of August 26th. However, on August 25th, Britain announced that her guarantee of Polish independence had been formalized by an alliance between the two countries . Hitler wavered and postponed his attack to September 1, while trying on 26th of August to dissuade the British and the French from interfering in the eventual conflict. The negotiations convince Hitler that there is little chance the Western Allies would declare war on him, and even it this event, due to the lack of territorial guarantees to Poland they would be willing to negotiate a compromise favourable to Germany after its conquest of Poland. Meanwhile, the number of cross-border raids and sabotages by German Abwehr units, border skirmishes and overflights by high altitude reconnaissance aircraft increase, signalling to the Poles that war is imminent.

On August 29 Germany issues a final ultimatum to Poland, demanding the Polish Corridor, which the Poles refuse to consider. German Foreign Minister Joachim von Ribbentrop declares negotiations with Poland to be at an end. The Polish forces brace for war. On August 30 the Polish Navy sends its destroyer flotilla to Britain to avoid destruction by overwhelming German Navy (Kriegsmarine) on the small Baltic Sea. On the same day, Polish Marshal Rydz-Smigly announces mobilization of Polish troops for war but is pressured into revoking the order by the French, who still hope for diplomatic settelment and fail to realize that the Germans are fully mobilized and concentrated at the Polish border. On August 31, 1939, Hitler ordered hostilities against Poland to start at 4:45 the next morning.

Details of the campaign

Plans

German plan

The German plan Fall Weiss for what became known as the September campaign, was created by General Franz Halder, chief of the general staff, and directed by General Walther von Brauchitsch, the commander in chief of the upcoming campaign. The plan called for start of hostilities before the declaration of war and to pursue the doctrine of lightning war, later known as the blitzkrieg. The novel conept of blitzkrieg called for German tanks (panzer)s to attack in massed formations, break through enenemy front, isolate segments of the enemy, surrounded and destroy them. The armored forces would be followed by slower infantry, which would relieve armored forces from the burden of destroying the encirled units, thus the armored forces would be free to continue their advance.

Poland was a country all too well suited for the demonstration of blitzkrieg ruthless efficiency. It was a flat, plain country, its frontiers immensely long, close to 3,500 miles. Its long western and northern (facing East Prussia) border with Germany (1,250 miles) had been extended in the aftermath to Munich Agreement of 1938 by another 500 miles on its southern border, pursuing the German occupation of Bohemia and Moravia and creation of German puppet state of Slovakia, so that Poland's southern flank became exposed to invasion.

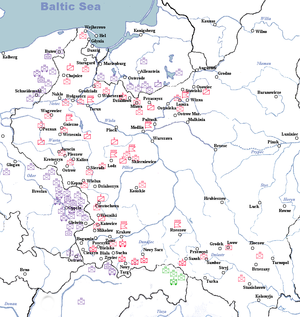

German planners intended to fully utilise their advantegous long border with the great enveloping maneuver of All Weiss. German units were to invade Poland from three directions:

- main attack from Germany mainland through western Polish border. This was to be carried out by Army Group South commanded General Gerd von Rundstedt, attacking from German Silesia and from the Moravian and Slovakian border: General Johannes Blaskowitz's 8th Army was to drive eastward against Łódz; General Wilhelm List's 14th Army was to push on toward Kraków and to turn the Poles' Carpathian flank; and General Walter von Reichenau's 10th Army, in the centre, with the Army Group South of the group's armour, was to deliver the decisive blow with a northwestward thrust into the heart of Poland.

- second route of attack from northern Prusy area. General Fedor von Bock commanded an Army Group North comprising General Georg von Küchler's 3rd Army, which struck southward from East Prussia, and General Günther von Kluge's 4th Army, which struck eastward across the base of the Polish Corridor.

- tertiary attack by part of Army Group South allied Slovak units from the territory of Slovakia

All three assaults were to converge on Warsaw, while the main Polish army were to be encircled and destroyed west of the Vistula. Fall Weiss was initiated on 1 September of 1939, and was the first operation of the Second World War.

Polish plan

The Polish defence plan was shaped by the politicians' determination to deploy directly at the front. With the most valuable natural resources, industry and highly populated regions near the western border (Silesia region), Polish policy was centered on protection of those regions, especially as many politicians feared that if Poland should retreat from the regions disputed by Germany (like the Gdansk corridor, cause of the famous 'Danzig or War' ultimatum), Britain and France would sign a separate peace with Germany, similar to the Munich Agreement of 1938, especially as none of those countries specifically guaranteed Polish borders and territorial integrity. On that grounds French advice to Poland to deploy bulk of Polish forces behind Vistula and San rivers was disregarded, even though it was supported as a reasonable strategy by some Polish generals.

The plan to defend the borders contributed vastly to the Polish defeat, as during the September campaign Polish forces were stretched thin on the very long border, and lacking compact defence lines and good defence positions, were often encircled by the mobile German forces. Approximately one-third of Poland's forces were concentrated in or near the Polish Corridor (in northeastern Poland), where they were perilously exposed to a double envelopment--from East Prussia and the west combined. In the south, facing the main avenues of a German advance, the Polish forces were thinly spread. At the same time, nearly another one-third of Poland's forces were massed in reserve in the north-central part of the country, between major cities of Łódz and Warsaw, under the commander in chief, Marshal Edward Rydz-Smigly. The Poles' forward concentration in general forfeited their chance of fighting a series of delaying actions, since their foot-marching army was unable to retreat to their defensive positions in the rear or to man them before being overrun by the invader's mechanized columns.

The Polish army had a fall-back plan, involving retreat behind their main rivers, to the southeastern voviodships and their lenghty defence (the Romanian bridgehead plan). The UK and France estimated that Poland should be able to defend that region for 2-3 months, while Poles estimated they could hold it for at least 6 months. This Polish plan was based around the expectation that Western Allies would keep their end of the signed alliance treaty and quickly start an offensive of their own. However, neither the French nor the British government had made plans to attack Germany while the Polish campaign was fought. Their plans were based on the experiences of the First World War and they expected to wear down Germany in trench warfare, eventually forcing Germany to sign a peace treaty and restore Polish independence. The Polish government, however, was not notified of this strategy and based all of its defence plans on the expectation of a quick relief action by their Western Allies. In any case, the Polish plan for defence of the south-east region (Romanian Bridgehead) was rendered obsolete overnight by the unexpected attack by the Soviet Union on 17th September, which opened a second front behind the Polish army back. Although the secret appendix of the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact about the Soviet alliance with Nazi Germany and their policy towards Poland had been uncovered by the Western Allies' intelligence, it was never shared with Poland.

The political decision to defend the border was not the only strategic mistake of the Polish high command. Polish pre-war propaganda stated that any German invasion would be easily repelled, so that the eventual Polish defeats in the September campaign came as a shock to many civilians, who, unprepared for such news and with no training for such an event, panicked and retreated east, spreading chaos, lowering troop morale and making road transportation for Polish troops very difficult. The propaganda also had some negative consequences on Polish troops themselves, whose communications, disrupted by German mobile units operating in the rear and civilians blocking roads, was further thrown in chaos by the bizarre reports from Polish radio stations and newspapers, which often reported imaginary victories and other military operations. This led to some Polish troops being encircled or taking a stand against overwhelming odds, when they thought they were actually counterattacking or would receive reinforcements from other victorious areas soon.

Phase 1: German aggression

Following a number of German-staged incidents (Operation Himmler), which gave Germany propaganda the reason to claim they were acting in self-defense, the first regular act of war took place on September 1, 1939, at 04:40 hours, when Germany's Luftwaffe (air force) attacked the Polish town of Wieluń, destroying 75% of the city and killing close to 1,200 people, most of them civilians. Five minutes later, at 04:45 hours, the old German battleship Schleswig-Holstein opened fire on the Polish enclave of Westerplatte at Free City of Gdańsk on the Baltic Sea. At 08:00 hours, German troops, still with no formal declaration of war issued, attacked Poland near the town of Mokra. Later that day, the Germans opened fronts along Poland's western, southern and northern borders, while German aircraft began raids on Polish cities. Main routes of attack led eastwards, from Germany mainland through western Polish border. Supporting attacks were carried by the second route of attack from northern Prusy region and a tertiary attack by German and allied Slovak units (Army "Bernolak") from the territory of German-allied Slovakia. All three assaults were converged on the Polish captial of Warsaw,

In the meantime, the Allied governments declared war on Germany on September 3. However, they failed to provide any meaningful support to Poland and the German-French border was calm, although majority of German forces, including eighty-five percent of their armed forces, was engaged in Poland. This marked the begining of the Phony War.

Despite some Polish successes in minor border battles, German technical, operational and numerical superiority forced the Polish armies to withdraw from the borders, towards Warsaw and Lwów. The Luftwaffe gained air superiority early in the campaign. By September 3, when Kluge in the north had reached the Vistula river and Küchler was approaching the Narew River, Reichenau's armour was already beyond the Warta river; two days later his left wing was well to the rear of Lódz and his right wing at town of Kielce; and by September 8 one of his armoured corps was in the outskirts of Warsaw, having advanced 140 miles in the first week of war. Light divisions on Reichenau's right were on the Vistula between Warsaw and town of Sandomierz by September 9, while List, in the south, was on the river San above and below town of Przemysl. At the same time, the 3rd Army tanks, led by Guderian, crossed the Narew attacking the line of the Bug River, already encirling Warsaw. All the German armies had made progress in fulfilling their parts of the Fall Weiss plan. The Polish armies were splitting up into uncoordinated fragments, some of which were retreating while others were delivering disjointed attacks on the nearest German columns.

Regions of Pomerania, Wielkopolska and Silesia were abandoned by Polish forces in the first week of the campaign, after the series of battles known as the battle of the border. Thus the Polish plan for border defence was proven a dismal failure. On September 10 the Polish commander in chief, Marshal Edward Rydz-Smigly, ordered a general retreat to the southeast, towards the so-called Romanian bridgehead. Meanwhile the Germans were tightening their net around encircled Polish forces west of the Vistula (in the Lódz area and, still farther west, around Poznan) but also penetrating deeply into eastern Poland. Warsaw, under heavy aerial bombardment from the first hours of the war, was first attacked on 9 September and was put under siege from September 13. Around that time advanced German forces have also reached the city of Lwów, a major metropolis of the eastern Poland.

The largest battle during this campaign (Battle of Bzura) took place near the Bzura river west of Warsaw from 9 September to 18 September, when Polish armies "Poznań" i "Pomorze", retreating from the border area of Polish Corridor, attacked the flank of the advancing German 8th army. This Polish attempt at a counter-attack which failed after an initial success. Polish defated in this battle marked the effective end of the Polish ability to take initative and counterattack in the large scale. Polish government (of president Ignacy Mościcki) and high command (of General Edward Rydz-Śmigły had left Warsaw in the first days of the campaign and headed south-east, arriving in Brześć on 6th September. General Rydz-Śmigły ordered the Polish forces to retreat in the same direction, behind the Vistula and San rivers, begining the preparations for the long defence of the Romanian bridgehead area.

Phase 2: Soviet aggression

The Polish defense was already broken, with their only hope being reorganising in the south-eastern regions, when on September 17, 1939, the Soviet Red Army, divided into the Bielorussian and Ukrainian fronts, invaded the eastern regions of Poland that had not yet been involved in military operations. While the Soviet diplomacy claimed that they were 'protecting the Ukrainian and Belorussian minorities inhabiting Poland in view of Polish imminent collapse', in fact they were acting in co-operation with Nazi Germany, carrying out their part of a secret deal (the division of Europe into Nazi and Soviet spheres of influences, as specified in the secret appendix of the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact). Polish border defences forces (Korpus Ochrony Pogranicza) in the east, (about 25 battalions) were unable to defend the border and were further ordered by Edward Rydz-Śmig ly to fall back and not to engage the Soviets. This however did not prevent some clashes and small battles.

The Soviet invasion was one of the decisive factors that convinced the Polish government that the war in Polish territory was lost. Prior to the Soviet attack from the East, the Polish fall-back military plan called for long-term defence against Germany in the southern-eastern part of Poland (near the Romanian border), while awaiting relief from an attack on the western border with Germany by the Western Allies. Facing two powerful enemies--Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union--the Polish government decided that it was impossible to carry out the defence on Polish territories. However it refused to surrender or negotiate for peace with the Germany and ordered all units to evacuate Poland and reorganize in France.

Meanwhile, Polish forces trying to move towards the Romanian bridgehead area, still actively resisted the German invasion. During 17-20 September the Battle of Tomaszów Lubelski, second biggest battle of the campaign took place. Despite a series of intensifing German attacks, Warsaw, defended by quickly reorganised retreating units, civilian volunteers and milita held out until its capitulation on 28 September. The Modlin Fortress north of Warsaw, capitulated on 29 September, after intense 16-days battle. Some isolated Polish garrisons managed to hold their positons long after being sourrounded by German forces. Westerplatte enclave tiny garrison capitulated on 7 September. Oksywie garrison held until the 19th September. Polish defenders on the Hel peninsula on the shore of the Baltic Sea held out until 2 October. The capitulation of the last operational unit of the Polish army, the Samodzielna Grupa Operacyjna "Polesie" of General Franciszek Kleeberg after a 4-day Battle of Kock near Lublin on 6 October, marked the end of the September Campaign.

Important battles

Some of the more notable engagements of the September Campaign are:

- Battle of the border (September 1 - September 7) - series of battles, which caused Polish forces to abandon the defence of the borders

- Battle of Bzura (September 9 - September 18) - failed Polish counter-attack, the biggest battle of the campaign

- Battle of Warsaw (September 8 - September 28) - siege of the Polish capital

- Battle of Tomaszów Lubelski (September 17 - September 20) - second biggest battle of the campaign

- Battle of Kock (October 2 - October 5) - the last battle of the campaign, marking the capitualtion of the last regular unit of the Polish army

Aftermath

At the end of the September Campaign, Poland was divided among Nazi Germany, Soviet Union, Lithuania and Slovakia. Nazi Germany annexed parts of Poland, while the rest was governed by the so-called General Government.

Poland was conquered and divided between Germany and Soviet Union, the forces of which met and greeted each other on Polish soil. On September 28 another secret German-Soviet protocol modified the arrangements of August: all Lithuania was to be a Soviet sphere of influence, not a German one; but the dividing line in Poland was changed in Germany's favour, being moved eastward to the Bug River.

About 65,000 Polish troops were killed and 680,000 were captured by the Germans (420,000) or Soviets (240,000). Up to 120,000 Polish troops withdrew to neutral Romania (through the Romanian Bridgehead) and Hungary and 20,000 to Latvia and Lithuania, with the majority eventually making their way to France or Britain. Most of the Polish Navy succeeded in evacuating to Britain as well.

]

Neither side - Germany, Western Allies or the Soviet Union - expected that the German invasion of Poland would lead to the war that would surpass the First World War in its scale and cost. Hitler didn't want to attack west, not in the 1939. German war machine was not yet ready. It would be months before Hitler would see the futility of his peace negotiation attempts with Great Britain and France. Years before the war would be joined by the Japan, Soviet Union and the United States and became truly the 'world war'. Nonetheless, what was not visible to most politicians and generals in 1939, is clear from the historical perspective. The Polish September Campaign marked the begining of the Second World War in Europe, which combined with the Pacific War in 1941 would form the conflict known as Second World War.

The invasion of Poland led to Britain and France declaring war on Germany on September 3, however they did little to affect the outcome of the September Campaign. This lack of direct help during September 1939 led many Poles to believe that they had been betrayed by their Western allies. In the meantime Poland, fulfilling her alliance obligations, did not surrender in 1939, but rather set up a government-in-exile (see Polish Government in Exile) in France (later in the United Kingdom) connected to the extensive underground civil and military organisation (Polish Secret State) as legal successors to their pre-1939 government. During the German occupation, the Poles continued their struggle as one of the most restive and organised populations under Nazi rule. Until the United States and Soviet Union entered the war, Poland, even with its territories occupied, had the third biggest army at the Western Allies' disposal.

The Polish campaign was important as the first step in Hitler's drive for "living space" (Lebensraum) for Germans in Eastern Europe (Generalplan Ost), and as the blitzkrieg decimated urban residential areas, civilians soon became indistinguishable from combatants. The forthcoming Nazi occupation (General Government, Reichsgau Wartheland) was one of the most brutal episodes of World War II, resulting in over 6 million Polish deaths (over 20% of country's inhabitants), including the mass murder of 3 million Polish Jews in extermination camps like Auschwitz. Soviet occupation, while shorter, also resulted in millions of deaths, when all who were deemed dangerous to the communist regime were subject to Sovietization, forced resettlement, imprisonment in labour camps (the Gulags) or simply murdered, like Polish officers in the Katyn massacre. Soviet atrocities commenced again after Poland was 'liberated' by the Red Army in 1944, with events like the persecutions of Armia Krajowa soldiers and executions of their leaders.

Opposing forces

Germany

Economic base

German was well prepared for the invasion of Poland, although it was not expecting this campaign to turn into a 6-years long global conflict. German economy was for years geared toward production of military equipment and supplies, and was fully capable of creating an army that could successfully inaved its neighbours.

Wehrmacht

The firepower of a German infantry division far exceeded that of a Polish (as well as French and British) division. The standard German division on the eve of the Second World War included 442 machine guns, 135 mortars, 72 antitank guns, and 24 howitzers.

Germany had not only a large, numerical advantege over Polish forces, but their organisation and command structure was much more efficient. While German forces were not as mobile or numerous as they would be in the later stages of the Second World War, the six armoured (panzer) divisions of the Wehrmacht comprised some 2,400 tanks, organized into divisions and with revolutionary, new operational doctrine. In accordance with the ideas of Heinz Guderian, the German tanks and mechanized support units like motorized artillery were used in massive mechanized spearhead (Schwerpunkt) attacks, serving as highly mobile units to punch holes in the enemy line and isolate selected enemy units, which were then encircled and destroyed by infantry while the armored and mechanized forces pushed forward to repeat the process, eventually breaking through enemy frontlines and then dispersing, causing confusion in the rear areas and severing lines of supply and communication. Those deep drives into enemy territory by panzer divisions were followed by less mobile mechanized infantry and foot soldiers. Wermacht was closly supported by Luftwaffe, especually by dive bombers that attacked and disrupted the enemy's supply and communications lines and spread panic and confusion in its rear, thus further paralyzing enemy's defensive capabilities. Mechanization was the key to this German tactic, revealed to the war first in the September campaign and nickanmed blitzkrieg, or "lightning war," by contemporary journalist, who found the name fitting because of the unprecedented speed and mobility that were its underlying characteristics.

Despite the term blitzkrieg being coined during the Polish September Campaign of 1939, historians generally hold that German operations during it were more consistent with more traditional methods. The Wehrmacht's strategy was more inline with Vernichtungsgedanken, or a focus on envelopment to create pockets in broad-front annihilation. Panzer forces were deployed among the three German concentrations without strong emphasis on independent use, being used to create or destroy close pockets of Polish forces and seize operational-depth terrain in support of the largely unmotorized infantry which followed.

Luftwaffe

Aircraft (particularly fighter and ground attack aircraft) played a major role in the fighting. Bomber aircraft purposefuly attacked cities and civilian targets causing huge losses amongst the civilian population in what became known as terror bombings. The Luftwaffe forces consisted of 1180 fighter aircraft, mainly Me 109s, 290 Ju 87 Stuka dive bombers, 290 conventional bombers, mainly of the He 111 type, and an assortment of 240 naval aircraft.

The German Air Force, or Luftwaffe, was also the best force of its kind in 1939. It was a ground-cooperation force designed to support the Army, but its planes were superior to nearly all Allied types. In the rearmament period from 1935 to 1939 the production of German combat aircraft steadily mounted. The standardization of engines and airframes gave the Luftwaffe an advantage over its opponents. Germany had an operational force of 1,000 fighters and 1,050 bombers in September 1939.

Kriegsmarine

At sea the odds against Germany were much greater in September 1939 than in August 1914, since the Allies in 1939 had many more large surface warships than Germany had. At sea, however, there was to be no clash between the Allied and the German massed fleets but only the individual operation of German pocket battleships and commerce raiders. In 1939 the Germany did have an advantege over tiny Polish fleet, and Western Allies were unwilling and unprepared to challenge Kriegsmarine on the small, land-locked Baltic Sea.

Poland

Economic base

Between 1936 and 1939, Poland invested heavily in industrialization of the Centralny Okręg Przemysłowy, chosen for being reasonably far from both the Soviet and German frontiers. That heavy spending on military industry pushed much of the spending on actual weapons into 1940 - 42. Poland had been preparing for defensive war for many years, however most plans assumed German aggression would not happen before 1942. Polish military industry development and fortifications were scheduled to be completed in that year, and newer tanks and aircraft were just entering production or would shortly.

The French loaned Poland 2.6 billion francs over a 5 year period starting in September 1936. That added 12% to the annual Polish military budget. The Polish defense budget for 1938-39 was 800 million złoty, of which:

- Armored force - 13.7 million

- Artillery - 16 million

- Air Force - 46.3 million

- Navy - 21.7 million

- Cavalry - 58 million

To raise funds for the industrial development, Poland was selling much of the modern equipment it produced: for example, anti-tank guns were sold to Britain, and planes were exported to Greece.

Polish Army

The Polish army was fairly strong in numbers (~1 million soldiers), but many of them were not mobilised by the 1st September, as the Polish government, advised in this by the British and French governments, constantly hoped that the war could be resolved (at least, for the time being) by diplomatic channels. Less than half of the Polish armed forces had been mobilized by 1 September, and only one-quarter (600,000) were fully equipped and in assigned positions when hostilities commenced. Thus many soldiers, mobilised after 1st September, failed to reach the designated staging areas, and, together with normal civilians, sustained significant casualties when public transport (trains and roads filled with refugees) became targets of the German air force.

Poland possessed numerically inferior armoured forces. Polish units were dispersed within infantry and unable to effectively engage in any major armor battles. The Germans opposing them had 3,000 tanks, organised into independent divisions under blitzkrieg doctrine. In terms of equipment, the Poles had 132 7TP light tanks, which were capable of destroying any German armour, including the Panzer IV, and less than 300 much weaker tankettes.

In addition to tanks, Poland successfully used armoured trains against Germans, who were unprepared to face this kind of combat vehicle, considered in '39 too obsolete by German planners to be given any serious consideration. Although the trains proved indeed vulnerable to air attack, the losses that the Germans incurred against Polish trains convinced them to reintroduce this type of vehicle into their own army after the September Campaign.

Organisation and operational doctrine of the Polish Army was shaped by the experiences of the only recent, major conflict that independed Second Polish Republic took part in: the Polish-Soviet War (1919-1921). Unlike the First World War, was a conflict in which mobility and cavalry played a decisive role. Thus Polish high command drew a lesson differend both from Western Allies and Germany, with their western front experience. France and Britian victory in the First World War caused them to remain conservative and expect the new war would be similar experience of trench warfare. Germany military theoories were based upon the notion that successfull offensive will be based on the new inventions - tanks and planes. Poland stood in the middle: acknowledging the benefits of mobility, but unwilling (and unable) to invest heavily in the expensive and unproven new inventions, it has turned to cavalry, which was considered to be the elite troops of the Polish army. During the September Campaign, Polish cavalry would prove to be much more successful than then anybody, Germans included, could have anticipated. Polish cavalry brigaes, contrary to the common myth, were used as a mobile infantry, and were quite successful against the German infantry. Cavalry charges were rare but succesfull, especially when used against normal infantry in unentrenched positions. However, while Polish cavalry matched German Panzers in speed and anti-infantry effectiveness, in the end it could simply not stand its ground against the tanks.

Among interesting equipment used with success by Polish forces was the 7.92 mm Karabin przeciwpancerny wz.35 anti-tank rifle. It was quite successful against German light tanks, although, as with most of the Polish modern equipment, production was just beginning when the war started and thus it wasn't fielded in numbers large enough to significantly change the war outcome.

Polish Air Force

The Polish Air Force was at a severe disadvantage against the German Luftwaffe. Although its pilots were highly trained, the Polish Air Force lacked modern fighter aircraft, and the Germans had gross numerical superiority: Poland had approximately 400 aircraft, including 169 fighters, and Germany had approximately 3,000 aircraft. The development program of the Polish airforce was slowed in 1926 in the aftermath of Józef Piłsudski's May coup d'etat, as Piłsudski considered the airforce to be of less importance than other military branches.

In 1939, the Polish main fighter, the PZL P.11, designed in early-1930s, was becoming obsolete, the slightly better PZL P.24 was used solely for export and PZL P.50s and several other projects, which were supposed to have better parameters than contemporary German fighters, were still on the drawing board. As the result, the German Messerschmitt Bf 109 and Bf 110 fighters were faster and better armed then anything Poles had in 1939, and most German bombers could also outrun the Polish fighters. On the other hand, P.11s were more maneuverable, and despite the German superiority in speed, armament and numbers, P.11s downed a considerable number of German aircraft, including fighters. The exact numbers are not verified, but some sources claim that at least one German aircraft was shot down for each P.11 lost (a figure of 107 to 141 German aircraft shot down for the loss of 118 Polish aircraft are most often given).

One of the most interesting units in the Polish airforce arsenal was the twin-engine medium bomber, the PZL.37 Łoś. Before the war it was one of the world's most modern and outstanding bombers. Smaller than most contemporary medium bombers, it was still able to carry a heavier bomb load than comparable aircraft, including the famous Vickers Wellington. It was relatively fast and easy to handle. Thanks to a landing gear with double wheels, it could operate from rough fields or meadows. The only drawback was its relatively weak defensive armament, consisting of 3 machine guns. Its range was also limited, but the Łoś was not meant to be a long range bomber. During the September Campaign, despite their good performance, they were too few in number to change the outcome, and, often lacking fighter cover, they sustained heavy losses.

Few planes of the Polish air Force were destroyed on ground, as most had been deployed to temporary secret airstrips. The fighter planes were grouped in 15 escadres. Five of them constituted the Pursuit Brigade (Polish: Brygada Pościgowa), deployed in Warsaw area. The bombers, grouped in 9 escadres of the Bomber Brigade (Brygada Bombowa), attacked armoured columns, suffering heavy losses. Seven reconnaissance and 12 observation escadres, deployed to particular Polish Armies, were intensively used for reconnaissance. However, the Polish pilots, while highly trained and motivated, faced a superior numerical opponent in superior designs with much better command structure. Germany achieved air superiority around day three of the campaign, although Polish Air Force manged to remain operational for the two first weeks of the September campaign. At that point, the Polish Air Force ceased to exist as a fighting force, as most planes were either destroyed in combat or had to be abandoned on the ground due to lack of supplies and spare parts, in the face of rapidly advancing German land troops. A few remaining aircraft were either captured by Germans or withdrawn to Romania and taken over by that country. A great number of pilots and air crews managed to break through to France and later Britain through various routes.

- Airplanes:

- PZL P.7, fighter

- PZL P.11, fighter

- PZL P.24, fighter, an export variant of the PZL P.11, not used during the September Campaign

- PZL.37 Łoś, twin-engine medium bomber

- PZL.23 Karaś, light bomber and reconnaissance aircraft

Polish Navy

The Polish Navy was a small fleet composed of destroyers and submarines. Most of Polish surface units followed Operation Pekin, leaving Polish ports on 20th August, evading German forces and escaping to the North Sea to join with the British Royal Navy. Submarine forces were realising Operation Worek, with the goal of engaging and damaging German shipping in the Baltic Sea, but with much less success.

- Warships (in service during September 1939)

- ORP Gryf, large minelayer, sunk by German bombers near Hel

- ORP Błyskawica, a destroyer, escaped to United Kingdom

- ORP Wicher, a destroyer, sunk by German bombers near Hel

- ORP Grom, a destroyer, escaped to United Kingdom

- ORP Burza, a destroyer, escaped to United Kingdom

- ORP Orzeł, a submarine, escaped to United Kingdom

- ORP Sęp, a submarine, interned in Sweden

- ORP Wilk, a submarine, escaped to United Kingdom

- ORP Ryś, a submarine, interned in Sweden

- ORP Żbik, a submarine, interned in Sweden

- ORP Mewa, Jaskółka, Rybitwa, Czajka, Żuraw, Czapla - 6 small minesweepers. ORP Mewa, Jaskółka and Czapla were sunk by German bombers near hel and Oksywie, others have been captured and salvaged by Germans.

- ORP Mazur, old torpedo destroyer from First World War, sunk by German bombers near Hel

- two gunboats

In addition, many ships of Polish Merchant Navy joined the British merchant fleet and took part in various convoys during the war.

Myths

The Polish military was so backward they fought tanks with cavalry: Although Poland had 11 cavalry brigades and its doctrine emphasized cavalry units as elites, other armies of that time (including German) also fielded and extensively used cavalry units. Polish cavalry never charged on German tanks nor entrenched machine guns but usually acted as mobile infantry units and executed cavalry charges only in rare situations.

The Polish air force was destroyed on the ground in the first days of the war: The Polish Air Forces, though numerically inferior and lacking modern fighters, were not destroyed on airfields and remained active in the first two weeks of the campaign, causing some harm to the Germans. Skilled Polish pilots who escaped to the United Kingdom after the German occupation were employed by the RAF during the Battle of Britain. Fighting from British bases, Polish pilots were also, on average, the most successful in shooting down German planes.2

Poland offered little resistance and surrendered quickly: It should be noted that the September campaign lasted only about one week less than the Battle of France in 1940, even through French forces had much better parity in terms of numerical strenght and equipment. 3

Order of battle

Poland:

Invading forces:

- German order of battle for Operation Fall Weiss

- Soviet order of battle for invasion of Poland in 1939

Notes

- Various sources contradict each other so the figures quoted above should only be taken as a rough indication of losses. The most common range brackets for casualties are: Polish casualties - 65,000 to 66,300; German casualties - 8,082 to 16,343, with missing in action from 5,029 to 320. The discrepancy in German casualties can be attributed to confusion between dead and missing and the fact that some German statistics still listed soldiers as missing decades after the war. Today the most common and accepted number for German casualties is 16,343. Soviet losses are estimated at 737 killed and 1,859 wounded. The often cited figure of 420,000 Polish prisoners of war represents only those captured by the Germans, as Soviets captured about 240,000 Polish POWs themselves, making the total number of Polish POWs about 660,000-690,000. Equipment losses are given as 89 German tanks and approximately 1,000 other vehicles to 132 Polish tanks and 300 other vehicles, 107-141 German planes to 327 Polish planes (118 fighters), 1 German small minelayer to 1 Polish destroyer, 1 minelayer and several support craft. Soviets lost approximately 42 tanks in combat while hundreds more suffered technical failures.

- No. 303 "Kościuszko" Polish Fighter Squadron formed from Polish pilots in United Kingdom almost 2 months after the Battle of Britain begun is famous for achieving the highest number of enemy kills during the Battle of Britain of all fighter squadrons then in operation.

- Polish to Germany forces in the September Campaign: 1 million soldiers 4,300 guns, 880 tanks, 435 aircraft to 1,8 million soldiers, 10,000 guns, 2,800 tanks, 3,000 aircraft. French and participating Allies to German forces in the Battle of France: 2,862,000 soldiers, 13,974 guns, 3,384 tanks, 3,099 aircraft 2 to 3,350,000 soldiers, 7,378 guns, 2,445 tanks, 5,446 aircraft.

See also

- Armenian quote

- History of Poland (1939-1945)

- Oder-Neisse line

- Polish cavalry brigade order of battle

- Polish contribution to World War II

- Western betrayal

- Yalta Conference

References

- Baliszewski Dariusz, Wojna sukcesów, Tygodnik "Wprost", Nr 1141 (10 October 2004), Polish, retrieved on 24 March 2005

- Baliszewski Dariusz, Most honoru, Tygodnik "Wprost", Nr 1138 (19 September 2004), Polish, retrieved on 24 March 2005

- Chodakiewicz, Marek Jan. Between Nazis and Soviets: Occupation Politics in Poland, 1939-1947. Lexington Books, 2004 (ISBN 0739104845).

- Gross, Jan T. Revolution from Abroad: The Soviet Conquest of Poland's Western Ukraine and Western Belorussia. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2002 (ISBN 0691096031).

- Kennedy, Robert M. The German Campaign in Poland (1939). Zenger Pub Co, 1980 (ISBN 0892010649).

- Lukas, Richard C. Forgotten Holocaust: The Poles Under German Occupation, 1939-1944. Hippocrene Books, Inc, 2001 (ISBN 0781809010).

- Majer, Diemut et al. Non-Germans under the Third Reich: The Nazi Judicial and Administrative System in Germany and Occupied Eastern Europe, with Special Regard to Occupied Poland, 1939-1945. Johns Hopkins University Press, 2003 (ISBN 0801864933)

- Prazmowska, Anita J. Britain and Poland 1939-1943 : The Betrayed Ally. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1995 (ISBN 0521483859).

- Rossino, Alexander B. Hitler Strikes Poland: Blitzkrieg, Ideology and Atrocity. Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 2003 (ISBN 0700612343).

- Smith, Peter Charles. Stuka Spearhead: The Lightning War from Poland to Dunkirk 1939-1940. Greenhill Books, 1998 (ISBN 1853673293).

- Sword, Keith. The Soviet Takeover of the Polish Eastern Provinces, 1939-41. Palgrave Macmillan, 1991, (ISBN 0312055706).

- Zaloga, Steve, and Howard Gerrard. Poland 1939: The Birth of Blitzkrieg. Oxford: Osprey Publishing, 2002 (ISBN 1841764086).

- Zaloga, Steve. The Polish Army 1939-1945. Oxford: Osprey Publishing, 1982 (ISBN 0850454174).

External links

- World War 2 Online Newspaper Archives - The Invasion of Poland, 1939

- The Campaign in Poland at WorldWar2 Database

- The Campaign in Poland at Achtung! Panzer

- German Statistics including September Campaign losses

- Brief Campaign losses and more statistics

- Fall Weiß - The Fall of Poland

- Agreement of Mutual Assistance Between the United Kingdom and Poland.-London, August 25, 1939.

- Poland's Defence War, a fairly detailed account of the Polish defense in 1939

- A timeline of the events in Poland in 1939

- Radio reports on the German invasion of Poland and Nazi broadcast claiming that Germany's action is an act of defense

- [http://adolfhitler.ws/lib/proc/reply.html German reply to British Government's ultimatum of 3rd September, 1939

- 1 September 1939 Headline story on BBC: Germany invades Poland

- BBC portal dedicated to the start of IIWW in Europe