Mycobacterium

| Mycobacterium | |

|---|---|

| |

| TEM micrograph of M. tuberculosis. | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | |

| Phylum: | |

| Order: | |

| Suborder: | |

| Family: | Mycobacteriaceae

|

| Genus: | Mycobacterium Lehmann & Neumann 1896

|

| Species | |

|

See below. | |

Mycobacterium is a genus of Actinobacteria, given its own family, the Mycobacteriaceae. It includes many pathogens known to cause serious diseases in mammals, including tuberculosis and leprosy. The prefix "myco-" meaning both fungus and wax in Latin; its use here relates to the "waxy" compounds in the cell wall.

Common microbiologic characteristics of the genus

Mycobacteria are aerobic and nonmotile bacteria that are characteristically acid-alcohol fast. Mycobacteria are usually considered gram positive and they do not contain endospores, or capsules. Mycobacteria are slightly curved or straight rods between 0.2-0.6 µm wide by 1.0-10µm long.

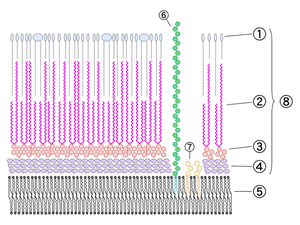

All Mycobacteria share a characteristic cell wall, thicker than in many other bacteria, which is hydrophobic, waxy, and rich in mycolic acids/mycolates. The mycobacterial cell wall makes a substantial contribution to the hardiness of this genus.

Many Mycobacterium species adapt readily to growth on very simple subtrates, using ammonia or amino acids as nitrogen sources and glycerol as a carbon source in the presence of mineral salts. Optimum growth temperatures vary widely according to the species and range from 25°C to over 50°C.

Some Mycobacteria species can be very difficult to culture (fastidious), sometimes taking over two years to develop in culture. As well as being fastidious, some species also have extremely long reproductive cycles (M. leprae, for example, may take more than 20 days to proceed through one division cycle;E. coli, for comparison, takes only 20 minutes), making laboratory culture a slow process.

A natural division occus between slowly and rapidly growing species. Mycobacteria that form colonies clearly visible to the naked eye within 7 days on subculture are termed rapid growers, while those requiring longer periods are termed slow growers.

Slowly growing Mycobacteria

Rapidly growing Mycobacteria

Pigmentation Some mycobacteria produce carotenoid pigments without light. Others require photoactivation for pigment production. Photochromogens produce nonpigmented colonies when grown in the dark and pigmented colonies only after exposure to light and reincubation. Scotochromogens produce deep yellow to orange colonies when grown in either the light or dark. Nonphotochromogens are nonpigmented in the light and dark or have only a pale yellow, buff or tan pigment that does not intensify after light exposure.

Mycobacteria appear phenotypically most closely related to members of Nocardia, Rhodococcus and Corynebacterium.

Staining characteristics Mycobacteria are classical acid-fast organisms. Stains used in evaluation of tissue specimens or microbiological specimens include Fite's stain, Ziehl-Neelsen stain, and Kinyoun stain.

Mycobacterium ecological characterisitics

Mycobacteria are widespread organisms, typically living in water (including tap water treated with chlorine) and food sources. Some, however, including the tuberculosis and the leprosy organisms, appear to be obligate parasites and are not found as free-living members of the genus.

Mycobacteria as pathogens

Mycobacteria can colonize their hosts without the hosts showing any adverse signs. For example, billions of people around the world are infected with M. tuberculosis but will never know it because they will not develop symptoms.

Mycobacterial infections are notoriously difficult to treat. The organisms are hardy due to their cell wall, which is neither truly Gram negative nor positive, and unique to the family, they are naturally resistant to a number of antibiotics that work by destroying cell walls, such as penicillin. Also, because of this cell wall, they can survive long exposure to acids, alkalis, detergents, oxidative bursts, lysis by complement and antibiotics which naturally leads to antibiotic resistance. Most mycobacteria are susceptible to the antibiotics clarithromycin and rifamycin, but antibiotic-resistant strains are known to exist.

Medical classification

Mycobacteria can be classified into several major groups for purpose of diagnosis and treatment: M. tuberculosis complex which can cause tuberculosis: M. tuberculosis, M. bovis, M. africanum, and M. microti; M. leprae which causes Hansen's disease or leprosy; Nontuberculous mycobacteria (NTM) are all the other mycobacteria which can cause pulmonary disease resembling tuberculosis, lymphadenitis, skin disease, or disseminated disease.

Phenotypic testing of Mycobacteria

Various phenotypic tests can be used to indentify and distinguish different Mycobacteria species and strains.

Phenotypic testing of Mycobacteria

Established Species of Mycobacteria

- M. abscessus

- M. africanum

- M. agri

- M. aichiense

- M. alvei

- M. arupense

- M. asiaticum

- M. aubagnense

- M. aurum

- M. austroafricanum

- Mycobacterium avium complex (MAC), is a group of species which are a significant cause of death in AIDS patients. Species in this complex include:

- M. avium

- M. avium paratuberculosis, which has been implicated in Crohn's disease in humans and Johne's disease in sheep

- M. avium silvaticum

- M. avium "hominissuis"

- M. boenickei

- M. bohemicum

- M. bolletii

- M. botniense

- M. bovis

- M. branderi

- M. brisbanense

- M. brumae

- M. canariasense

- M. caprae

- M. celatum

- M. chelonae,

- M. chimaera

- M. chitae

- M. chlorophenolicum

- M. chubuense

- M. colombiense

- M. conceptionense

- M. confluentis

- M. conspicuum

- M. cookii

- M. cosmeticum

- M. diernhoferi

- M. doricum

- M. duvalii

- M. elephantis

- M. fallax

- M. farcinogenes

- M. flavescens

- M. florentinum

- M. fluoroanthenivorans

- M. fortuitum

- M. fortuitum subsp. acetamidolyticum

- M. frederiksbergense

- M. gadium

- M. gastri

- M. genavense

- M. gilvum

- M. goodii

- M. gordonae

- M. haemophilum

- M. hassiacum

- M. heckeshornense

- M. heidelbergense

- M. hiberniae

- M. hodleri

- M. holsaticum

- M. houstonense

- M. immunogen

- M. interjectum

- M. intermedium

- M. intracellulare

- M. kansasii

- M. komossense

- M. kubicae

- M. kumamotonense

- M. lacus

- M. lentiflavum

- M. leprae, which causes leprosy

- M. lepraemurium

- M. madagascariense

- M. mageritense

- M. malmoense

- M. marinum

- M. massiliense

- M. microti

- M. monacense

- M. montefiorense

- M. moriokaense

- M. mucogenicum

- M. murale

- M. nebraskense

- M. neoaurum

- M. neworleansense

- M. nonchromogenicum

- M. novocastrense

- M. obuense

- M. palustre

- M. parafortuitum

- M. parascrofulaceum

- M. parmense

- M. peregrinum

- M. phlei

- M. phocaicum

- M. pinnipedii

- M. porcinum

- M. poriferae

- M. pseudoshottsii

- M. pulveris

- M. psychrotolerans

- M. pyrenivorans

- M. rhodesiae

- M. saskatchewanense

- M. scrofulaceum

- M. senegalense

- M. seoulense

- M. septicum

- M. shimoidei

- M. shottsii

- M. simiae

- M. smegmatis

- M. sphagni

- M. szulgai

- M. terrae

- M. thermoresistibile

- M. tokaiense

- M. triplex

- M. triviale

- Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex (MTBC),members are causative agents of human and animal tuberculosis. Species in this complex include:

- M. tuberculosis, the major cause of human tuberculosis

- M. bovis

- M. bovis BCG

- M. africanum

- M. canetti

- M. caprae

- M. pinnipedii'

- M. tusciae

- M. ulcerans, which causes the "Buruli", or "Bairnsdale, ulcer"

- M. vaccae

- M. vanbaalenii

- M. wolinskyi

- M. xenopi

References

- Diagnosis and Treatment of Disease Caused by Nontuberculous Mycobacteria. American Thoracic Society. Am J Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine. Aug 1997 156(2) Part 2 Supplement PDF format

- RIDOM - Ribosomal Differentiation of Medical Microorganisms [1]

- J.P. Euzéby: List of Prokaryotic Names with Standing in Nomenclature - Genus Mycobacterium [2]

See also

- Leprosy (Hansen's disease)

- Tuberculosis