Nicolaus Copernicus

Nicolaus Copernicus | |

|---|---|

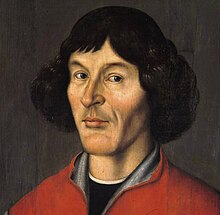

Portrait from his hometown, Toruń, beginning of the 16th century. | |

| Born | February 19, 1473, |

| Died | May 24, 1543 (aged 70), |

| Alma mater | Kraków University, Bologna University, Padua University, Ferrara University. |

| Known for | first modern formulation of a heliocentric theory of the solar system. |

| Children | (celibate cleric, no children) |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Mathematician, astronomer, jurist, physician, classical scholar, Catholic cleric, governor, administrator, military commander, diplomat, economist. |

Nicolaus Copernicus (February 19, 1473 – May 24, 1543) was the Polish astronomer who formulated a modern heliocentric model of the solar system. His epochal book, De revolutionibus orbium coelestium (On the Revolutions of the Celestial Spheres), is often conceived as the starting point of modern astronomy, as well as a central and defining epiphany in all the history of science.

Among the great polymaths of the Scientific Revolution, Copernicus was a mathematician, astronomer, jurist, physician, classical scholar, Catholic cleric, governor, administrator, military leader, diplomat and economist. Amid his extensive responsibilities, astronomy figured as little more than an avocation.

While the heliocentric theory had been attempted to formulated by Greek, Indian and Muslim savants centuries before Copernicus, his proof that the sun — rather than the Earth — is at the center of the solar system is considered among the most important landmarks in the history of modern science.

Life

Nicolaus Copernicus was born in 1473 in the city of Toruń (Thorn) in the Royal Prussia Region of the Kingdom of Poland.[1] He was educated at Kraków, Bologna, Padua and Ferrara, and spent most of his working life within the prince-bishopric of Warmia (Ermeland), in the town of Frombork (Frauenburg), where he died in 1543.

Childhood

Nicolaus Copernicus' father — a wealthy businessman, copper trader, and respected citizen of Toruń — died when Nicolaus was ten years old. Little is known of Nicolaus' mother, Barbara Watzenrode, except that she was born into a rich merchant family and appears to have predeceased her husband. After the elder Copernicus' death, Nicolaus' maternal uncle, Lucas Watzenrode, a church canon and later Prince-Bishop governor of the Archbishopric of Warmia, reared Nicolaus and his three siblings. The uncle's position facilitated Nicolaus' pursuit of a career within the church, enabling him to devote much time to his astronomy studies.

Copernicus had a brother and two sisters:

- Andreas became an Augustinian canon at Frombork.

- Barbara became a Benedictine nun.

- Katharina married Barthel Gertner, a businessman and city councillor.

Education

In 1491 Copernicus enrolled at the Kraków Academy (now Jagiellonian University), where he probably first encountered astronomy with Professor Albert Brudzewski. Astronomy soon fascinated him, and he began collecting a large library on the subject. Copernicus' library would later be carried off as war booty by the Swedes during "the Deluge" and is now at the Uppsala University Library.

After four years in Kraków, followed by a brief stay back home in Toruń, Copernicus went to study law and medicine at the universities of Bologna and Padua.

Copernicus' uncle financed his education and hoped that Copernicus too would become a bishop. Copernicus, however, while studying canon and civil law at Bologna, met the famous astronomer, Domenico Maria Novara da Ferrara. Copernicus attended Novara's lectures and became his disciple and assistant. The first observations that Copernicus made in 1497, together with Novara, are recorded in Copernicus' epochal book, De revolutionibus orbium coelestium.

In 1497 Copernicus' uncle was ordained Bishop of Warmia, and Copernicus was named a canon at Frombork Cathedral, but he waited in Italy for the great Jubilee of 1500. Copernicus went to Rome, where he observed a lunar eclipse and gave some lectures in astronomy and mathematics.

He would thus have visited Frombork only in 1501. As soon as he arrived, he requested and obtained permission to complete his studies in Padua, where he studied medicine (with Guarico and Fracastoro), including astrological medicine, and at Ferrara, where in 1503 he received his doctorate in canon law. It has been surmised that it was in Padua that he encountered passages from Cicero and Plato about opinions of the ancients on the movement of the Earth, and formed the first intuition of his own future theory. In 1504 Copernicus began collecting observations and ideas pertinent to his theory.

His Work

Having left Italy at the end of his studies, he came to live and work at Frombork. Some time before his return to Warmia, he received a position at the Collegiate Church of the Holy Cross in Wrocław (Breslau), Silesia, Bohemia, which he held for many years and only resigned for health reasons shortly before his death. Through the rest of his life, he performed astronomical observations and calculations, but only as time permitted and never in a professional capacity.

Coin reform

Copernicus worked for years with the Royal Prussian Diet, with Albert, Duke of Prussia and advised the Polish king Sigismund I the Old on monetary reform. In 1526 Copernicus wrote a study on the value of money Monetae Cudendae Ratio. In it, Copernicus formulated an early iteration of the theory, now called "Gresham's Law," that "bad" (debased) coinage drives "good" (un-debased) coinage out of circulation, 70 years before Gresham. He also formulated a version of quantity theory of money. As governor of Warmia, he administered taxes and dealt out justice.

During these years, Copernicus also traveled extensively on government business and as a diplomat, on behalf of the Prince-Bishop of Warmia.

Heliocentrism

In 1514 Copernicus made available to friends his Commentariolus (Little Commentary) — a short handwritten text describing his ideas about the heliocentric hypothesis . Thereafter he continued gathering data for a more detailed work.

In 1533, Johann Albrecht Widmannstetter delivered in Rome a series of lectures outlining Copernicus' theory. The lectures were heard with interest by Pope Clement VII and several Catholic cardinals.

On 1 November 1536, Archbishop of Capua Nicholas Schönberg wrote a letter to Copernicus from Rome:

Some years ago word reached me concerning your proficiency, of which everybody constantly spoke. At that time I began to have a very high regard for you... For I had learned that you had not merely mastered the discoveries of the ancient astronomers uncommonly well but had also formulated a new cosmology. In it you maintain that the earth moves; that the sun occupies the lowest, and thus the central, place in the universe... Therefore with the utmost earnestness I entreat you, most learned sir, unless I inconvenience you, to communicate this discovery of yours to scholars, and at the earliest possible moment to send me your writings on the sphere of the universe together with the tables and whatever else you have that is relevant to this subject...[2]

By then Copernicus' work was nearing its definitive form, and rumors about his theory had reached educated people all over Europe. Despite urgings from many quarters, Copernicus delayed with the publication of his book, perhaps from fear of criticism — a fear delicately expressed in the subsequent Dedication of his masterpiece to Pope Paul III. About this, historians of science David Lindberg and Ronald Numbers have written:

If Copernicus had any genuine fear of publication, it was the reaction of scientists, not clerics, that worried him. Other churchmen before him — Nicole Oresme (a French bishop) in the fourteenth century and Nicolaus Cusanus (a German cardinal) in the fifteenth — had freely discussed the possible motion of the earth, and there was no reason to suppose that the reappearance of this idea in the sixteenth century would cause a religious stir.[3]

In connection with the Galileo affair, Copernicus' book was suspended until corrected by the Index of the Catholic Church in 1616, because the Pythagorean doctrine of the motion of the Earth and the immobility of the Sun "is false and altogether opposed to the Holy Scripture".[4][5] These corrections were indicated in 1620, and nine sentences had to be either omitted or changed. [6] The book stayed on the Index until 1758. In that period Galileo Galilei was found guilty in 1633 for "following the position of Copernicus, which [is] contrary to the true sense and authority of Holy Scripture ..."[7], and was sent to his home near Florence where he was to be under house arrest for the remainder of his life in 1638.

The book

Copernicus was still working on De revolutionibus orbium coelestium (even if not convinced that he wanted to publish it) when in 1539 Georg Joachim Rheticus, a Wittenberg mathematician, arrived in Frombork. Philipp Melanchthon had arranged for Rheticus to visit several astronomers and study with them. Rheticus became Copernicus' pupil, staying with him for two years, during which he wrote a book, Narratio prima (First Account), outlining the essence of Copernicus' theory. In 1542 Rheticus published a treatise on trigonometry by Copernicus (later included in the second book of De revolutionibus). Under strong pressure from Rheticus, and having seen the favorable first general reception of his work, Copernicus finally agreed to give the book to his close friend, Tiedemann Giese, bishop of Chełmno (Kulm), to be delivered to Rheticus for printing by Johannes Petreius at Nuremberg (Nürnberg).

Legend has it that the first printed copy of De revolutionibus was placed in Copernicus' hands on the very day he died, allowing him to take farewell of his opus vitae (life's work). He is reputed to have woken from a stroke-induced coma, looked at his book, and died peacefully.

Copernicus was buried in Frombork Cathedral. Archeologists had long vainly searched for his remains when, on November 3, 2005, it was announced that in August that year Copernicus' skull had been discovered (see "Grave," below).

Copernican system

Predecessors

Early traces of a heliocentric model are found in several anonymous Vedic Sanskrit texts composed in ancient India before the 7th century BCE. Additionally, the Indian astronomer and mathematician Aryabhata anticipated elements of Copernicus' work by over a thousand years.

Aristarchus of Samos in the 3rd century BCE elaborated some theories of Heraclides Ponticus (the daily rotation of the Earth on its axis, the revolution of Venus and Mercury around the Sun) to propose what was the first scientific model of a heliocentric solar system: the Earth and all other planets revolving around the Sun, the Earth rotating around its axis daily, the Moon in turn revolving around the Earth once a month. His heliocentric work has not survived, so we can only speculate about what led him to his conclusions. It is notable that, according to Plutarch, a contemporary of Aristarchus accused him of impiety for "putting the Earth in motion."

Copernicus cited Aristarchus and Philolaus in a surviving early manuscript of his book, stating: "Philolaus believed in the mobility of the earth, and some even say that Aristarchus of Samos was of that opinion." For reasons unknown (possibly from reluctance to quote pre-Christian sources), he did not include this passage in the published book. It has been argued that in developing the mathematics of heliocentrism Copernicus drew on not just the Greek, but also the work of Muslim astronomers, especially the works of Nasir al-Din Tusi (Tusi-couple), Mo'ayyeduddin Urdi (Urdi lemma) and Ibn al-Shatir. Copernicus also discussed the theories of Ibn Battuta and Averroes in his major work.

Ptolemy

The prevailing theory in Europe as Copernicus was writing was that created by Ptolemy in his Almagest, dating from about 150 A.D.. The Ptolemaic system drew on many previous theories that viewed Earth as a stationary center of the universe. Stars were embedded in a large outer sphere which rotated relatively rapidly, while the planets dwelt in smaller spheres between — a separate one for each planet.

Copernicus

Copernicus' major theory was published in the book, De revolutionibus orbium coelestium (On the Revolutions of the Celestial Spheres) during the year of his death, 1543, though he had arrived at his theory several decades earlier.

The Copernican system can be summarized in seven propositions, as Copernicus himself collected them in a Compendium of De revolutionibus that was found and published in 1878.

The major parts of Copernican theory are:

- Heavenly motions are uniform, eternal, and circular or compounded of several circles (epicycles).

- The center of the universe is near the Sun.

- Around the Sun, in order, are Mercury, Venus, Earth and Moon, Mars, Jupiter, Saturn, and the fixed stars.

- The Earth has three motions: daily rotation, annual revolution, and annual tilting of its axis.

- Retrograde motion of the planets is explained by the Earth's motion.

- The distance from the Earth to the sun is small compared to the distance to the stars.

The work itself was then divided into six books:

- General vision of the heliocentric theory, and a summarized exposition of his idea of the World

- Mainly theoretical, presents the principles of spherical astronomy and a list of stars (as a basis for the arguments developed in the subsequent books)

- Mainly dedicated to the apparent motions of the Sun and to related phenomena

- Description of the Moon and its orbital motions

- Concrete exposition of the new system

- Concrete exposition of the new system (continued)

Copernicanism

Copernicus' theory is of extraordinary importance in the history of human knowledge. Many authors suggest that few other persons have exerted a comparable influence on human culture in general and on science in particular.[citation needed] There are parallels with the life of Charles Darwin, in that both men produced a short early description of their theories, but held back on a definitive publication until late in life, against a backdrop of controversy, particularly with regard to religion.

Many meanings have been ascribed to Copernicus' theory, apart from its strictly scientific import. His work affected religion as well as science, religious belief as well as freedom of scientific inquiry. Copernicus' rank as a scientist is often compared with that of Galileo.

The Copernican theory challenged Aristotle's and Ptolemy's commonly accepted geocentric model of the universe endorsed by the Church. Copernicanism also opened the way to immanence, the view that a divine force, or divine being, pervades all that exists — a view that has since been developed further in modern philosophy.[citation needed] Immanentism also leads to subjectivism: to the theory that it is perception that creates reality, that there is no underlying reality that exists independent of perception.[citation needed] Thus some argue that Copernicanism demolished the foundations of medieval science and metaphysics.[who?]

A corollary of Copernicanism is that scientific law need not be congruent with appearance. This contrasts with Aristotle's system, which placed much more importance on the derivation of knowledge through the senses.

Copernicus' concept marked a scientific revolution. The publication of his De revolutionibus orbium coelestium is often taken to mark the beginning of the Scientific Revolution, together with the publication of Andreas Vesalius' De Humani Corporis Fabrica.[8]

Quotes

Copernicus:

- "For I am not so enamored of my own opinions that I disregard what others may think of them. I am aware that a philosopher's ideas are not subject to the judgment of ordinary persons, because it is his endeavor to seek the truth in all things, to the extent permitted to human reason by God. Yet I hold that completely erroneous views should be shunned. Those who know that the consensus of many centuries has sanctioned the conception that the earth remains at rest in the middle of the heaven as its center would, I reflected, regard it as an insane pronouncement if I made the opposite assertion that the earth moves."[9]

- "For when a ship is floating calmly along, the sailors see its motion mirrored in everything outside, while on the other hand they suppose that they are stationary, together with everything on board. In the same way, the motion of the earth can unquestionably produce the impression that the entire universe is rotating." [10]

- "Hence I feel no shame in asserting that this whole region engirdled by the moon, and the center of the earth, traverse this grand circle amid the rest of the planets in an annual revolution around the sun. Near the sun is the center of the universe. Moreover, since the sun remains stationary, whatever appears as a motion of the sun is really due rather to the motion of the earth."[11]

- "At rest, however, in the middle of everything is the sun. For, in this most beautiful temple, who would place this lamp in another or better position than that from which it can light up the whole thing at the same time? For, the sun is not inappropriately called by some people the lantern of the universe, its mind by others, and its ruler by still others. The Thrice Greatest labels it a visible god, and Sophocles' Electra, the all-seeing. Thus indeed, as though seated on a royal throne, the sun governs the family of planets revolving around it."[12]

Johann Wolfgang von Goethe:[citation needed]

- "Of all discoveries and opinions, none may have exerted a greater effect on the human spirit than the doctrine of Copernicus. The world had scarcely become known as round and complete in itself when it was asked to waive the tremendous privilege of being the center of the universe. Never, perhaps, was a greater demand made on mankind — for by this admission so many things vanished in mist and smoke! What became of our Eden, our world of innocence, piety and poetry; the testimony of the senses; the conviction of a poetic — religious faith? No wonder his contemporaries did not wish to let all this go and offered every possible resistance to a doctrine which in its converts authorized and demanded a freedom of view and greatness of thought so far unknown, indeed not even dreamed of."

Friedrich Nietzsche:[citation needed]

- "It gave me pleasure to contemplate the right of the Polish nobleman to upset with his simple veto the determinations of a [parliamentary] session; and the Pole Copernicus seemed to have made of this right against the determinations and presentations of other people, the greatest and worthiest use."

Allgemeine Deutsche Biographie (General German Biography), 1875: [13]

- "The nationality question has been a subject of various writings; an honoring controversy over the claim to the founder of our current world view is conducted between Poles and Germans, but as already mentioned nothing certain can be determined concerning the nationality of Copernicus' parents; the father seems to have been of Slavic birth, the mother German; he was born in a city whose municipal authorities and educated inhabitants were Germans, but which at the time of his birth was under Polish rule; he studied at the Polish capital, Krakau, then in Italy, and lived out his days as a canon in Frauenburg; he wrote Latin and German. In science, he is a man who belongs to no single nation, whose labors and strivings belong to the whole world, and we do not honor the Pole nor the German in Copernicus, but the man of free spirit, the great astronomer, the father of the new astronomy, the author of the true world view."

Johannes Rau as President of Germany (1999-2004) in an address to the Polish people in 1999:[14]

- "Poles and Germans have a common history of great scientists: Today we no longer perceive Copernicus, Hevelius, Schopenhauer and Fahrenheit as the property of one nation but as representatives of one transnational culture."

Declaration of the Polish Senate, June 12, 2003:

- "On the five hundred thirtieth anniversary of the birth, and the four hundred sixtieth anniversary of the death, of Mikołaj Kopernik, the Senate of the Polish Republic expresses its highest esteem and praise for this exceptional Pole, one of the greatest scientists in world history. Mikołaj Kopernik, world-famous astronomer and author of the landmark work, De revolutionibus orbium coelestium, "stopped the Sun and moved the Earth." He distinguished himself for Poland as an exceptional mathematician, economist, lawyer, physician and priest, as well as defender of Olsztyn Castle during the Polish-Teutonic war. May the memory of his achievements endure and be a source of inspiration to future generations."

Grave

In August 2005, a team of archeologists led by Jerzy Gąssowski, head of an archaeology and anthropology institute in Pułtusk, discovered what they believe to be Copernicus' grave and remains, after scanning beneath the floor of Frombork Cathedral. The find came after a year of searching, and the discovery was announced only after further research, on November 3. Gąssowski said he was "almost 100 percent sure it is Copernicus".

Forensic expert Capt. Dariusz Zajdel of the Central Forensic Laboratory of the Polish Police used the skull to reconstruct a face that closely resembled the features — including a broken nose and a scar above the left eye — on a Copernicus self-portrait.[15] The expert also determined that the skull had belonged to a man who had died about age 70 — Copernicus' age at the time of his death.

The grave was in poor condition, and not all the remains were found. The archeologists hoped to find deceased relatives of Copernicus in order to attempt DNA identification.

Nationality

It remains to this day a matter of dispute whether Copernicus should be regarded as German or Polish.[16] Since the late 18th century, but mainly during the 19th century when no Polish state existed, the issue was controversial, a fact which is on record at least since 1875[5]

While Numerous variations of his names are documented[17], he himself signed mostly with Coppernic until the mid-1530s, after which he preferred Copernicus. Thus, on the title page of his epochal book, Nicolai Copernici Torinensis De Revolutionibus Orbium Coelestium Libri VI (Six Books on the Revolutions of the Celestial Spheres, by Nicolaus Copernicus of T.), the astronomer's name appears in the Latin form, "Nicolaus Copernicus." First introduced by Herder in 1776 by replacing each of the three "c" with the letter "k", "Nikolaus Kopernikus" became popular in German references to Copernicus even though scholars argued for Coppernicus. The Polish rendering is "Mikołaj Kopernik". Poles claim that the ending "–nik" in the original[citation needed] form of the astronomer's name (Kopernik), meaning "one who works with (copper)," indicates Polish roots.[18]

Copernicus' father, possibly a Germanized Slav,[19] had been a citizen of Cracow but had left Poland's capital in 1460 to move to Thorn, known in Polish as Toruń. Most historians believe Copernicus' mother was German.[20] It has therefore been argued that Copernicus' "mother tongue" was German. While he was fluent in German and communicated with many German scholars, no direct evidence survives of the extent of his knowledge of Old Polish. As typical for the time, his main language for written communication was Latin.

An important inland port in the Hanseatic League, his home town was also part of the Prussian Confederation of cities with a mainly German citizenry which after the battle of Grunwald of 1410 sought independence from the Teutonic Knights. The Teutonic Order had founded the city two hundred years earlier but, as a result of the battle, they had to impose high taxes that hindered economic development. About two decades before Copernicus' birth, a secession led to the Thirteen Years' War and the Peace of Toruń of 1466; Prussia's western part willingly became subordinate to the Polish king as "Royal Prussia", while the eastern part remained under the administration of the Catholic Teutonic Order until 1525.

Copernicus was born, grew up and spend most of his life in Royal Prussia and therefore was a subject of the Polish crown.[21] This is cited as a major reason why he is commonly regarded as Polish. However, in Copernicus' time, nationality had yet to play as important a role as it would later, and people generally did not think of themselves primarily as Poles or Germans.[22] Indeed, he might have considered himself to be both at the same time.

Following extended studies in Italy, Copernicus spent most of his working life as a cleric in the bishopric of Warmia within Royal Prussia which, though subject to the Polish crown, enjoyed substantial autonomy — it had its own Diet, monetary unit and treasury (which Copernicus famously labored to place on a sound footing) and army.

Copernicus also oversaw the defense of the castle of Allenstein (Olsztyn) at the head of Royal Polish forces when the town was besieged by the forces of Albrecht Hohenzollern, Grand Master of the Teutonic Order during the Polish-Teutonic War (1519–1521). He also participated in the peace negotiations. Copernicus later served as a physician to Duke Albrecht who in 1551 financed the publishing of a volume of his astrological observations.[23]

Copernicus remained for the rest of his life a burgher of Warmia (Bishopric of Warmia). During the Protestant Reformation he remained a loyal subject of the Catholic Prince-Bishops and the Catholic Polish King when in 1525 Duke Albert and the Duchy of Prussia became a secular entity were monarch and burghers alike adopted Protestantism.

In 1757, Copernicus' book was removed from the Vatican's Index Librorum Prohibitorum, the list of books banned by the Catholic Church. Ever since, Poles have claimed that Copernicus was a Pole and Germans that he was a German. Before Copernicus and his ideas were widely embraced, it had been the reverse[citation needed].

The bust of Copernicus was in 1807 one of the first made to be enshrined later at the Walhalla temple, the German Hall of Fame. In 1875, when no Polish state and no Polish citizenship existed, with Poles being subjects to Russian, Austrian or Prussian monarchs for a century, the Allgemeine Deutsche Biographie article on Copernicus acknowledged the Polish aspects of his life. In Nazi Germany, Copernicus was claimed to be purely German;[24]. Since 1945, German assertions have returned to balanced views, while some Soviet bloc-era editions in socialist East Germany pronounced him a Pole. Acknowledgment of his connections to Poland notwithstanding, however, in Germany Copernicus is not considered "un-German" or "non-German." In 2003 he was declared eligible for the Unsere Besten (Our Best), a ranking of the "200 greatest Germans" organized by ZDF TV. Since 1989, three German TV satellites had been named de:DFS Kopernikus.

In Poland, in 1973, the 500th anniversary of Copernicus' birth was an occasion to celebrate the "great Pole"; a banknote was issued, bearing Copernicus' likeness. Thirty years later, on June 12, 2003, the Polish Senate declared him an "exceptional Pole."

These claims and counter-claims are somewhat anachronistic. In Copernicus' lifetime, "nationality" did not have the same meaning as today. Many ethnic Germans were loyal subjects of the Polish crown. The universal language of science was Latin, and academics throughout Europe communicated in that idiom.

See also

- Dedication to Pope Paul III

- List of things named after Copernicus

- Inferior and superior planets

- Polymath

- History of philosophy in Poland

- Copernicus Airport Wrocław

- Scientific revolution

Notes

- ^ Barbara Bieńkowska, The Scientific World of Copernicus: on the Occasion of the 500th Anniversary of His Birth, 1473-1973, 1973, p. 137: "His country was the province of ancient Royal Prussia, composed of his native Torun and Warmia, both components of the Polish state since 1454."

- ^ http://webexhibits.org/calendars/year-text-Copernicus.html

- ^ "Beyond War and Peace: A Reappraisal of the Encounter between Christianity and Science". American Scientific Affiliation article. Retrieved 2007-04-22. - Paper originally published in Church History (Vol. 55, No. 3, Sept. 1986).

- ^ Decree of General Congregation of the Index, March 5, 1616 (Translated from Latin)

- ^ Trial of Galileo [1]

- ^ Catholic Encyclopedia [2]

- ^ Papal Condemnation (Sentence) of Galileo, June 22, 1633, (Translated from Latin), Giorgio de Santillana, The Crime of Galileo (University of Chicago Press 1955), pp. 306-310

- ^ "Timeline of the Scientific Revolution". Saint Anselm College article. Retrieved 2007-04-22.

- ^ De Revolutionibus, Preface

- ^ De Revolutionibus, Book 1, Chapter 8

- ^ De Revolutionibus, Book 1, Chapter 10

- ^ De Revolutionibus, Book 1, Chapter 10

- ^ Allgemeine Deutsche Biographie: Nicolaus Copernicus, p.465, 1875 [http://mdz.bib-bvb.de/digbib/lexika/adb/images/adb004/@ebt-link?target=idmatch(entityref,adb0040463)

- ^ "Address by Mr. Johannes Rau" (DOC). Public Speeches and Addresses. 1999. Retrieved 2007-04-22.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ "Czy tak wyglądał Mikołaj Kopernik?". In Polish. Retrieved 2007-04-22.

- ^ Stuart Parkes, Understanding Contemporary Germany. ISBN 0-415-14123-0

- ^ Hans Koeppen et. al., Nicolaus Copernicus zum 500. Geburtstag, Cologne, 1973, ISBN 3-412-83573-2

- ^ "O historii i o współczesności". In Polish. Retrieved 2007-04-22.

- ^ "Revolution Of Astronomy By Copernicus". International World History Project article. Retrieved 2007-04-22.

- ^ "Revolution Of Astronomy By Copernicus". International World History Project article. Retrieved 2007-04-22.

- ^ "Nicolaus Copernicus". Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Retrieved 2007-04-22.

- ^ Norman Davies, God's Playground: A History of Poland, [3]. ISBN 0-231-05353-3.

- ^ "Great Lives from History: The Renaissance & Early Modern Era Nicolaus Copernicus". Salem Press summary of book. Retrieved 2007-04-22.

- ^ Diemut Majer, Non-Germans Under the Third Reich: The Nazi Judicial and Administrative System in Germany and occupied Eastern Europe with special regard to occupied Poland, 1939-1945, [4]. ISBN 0-8018-6493-3

References

- Angus Armitage (1951). The World of Copernicus, New York: Mentor Books. ISBN 0-8464-0979-8.

- Owen Gingerich (2004). The Book Nobody Read, Penguin Books. ISBN 0-14-303476-6.

- David C. Goodman and Colin A. Russell, eds. (1991). The Rise of Scientific Europe, 1500-1800. Dunton Green, Sevenoaks, Kent: Hodder & Stoughton: The Open University. ISBN 0-340-55861-X.

- Arthur Koestler - The Sleepwalkers: A History of Man's Changing Vision of the Universe, New York: Grosset & Dunlap, (1963, c1959). ISBN 0448001594.

- Alexandre Koyré (1973) The Astronomical Revolution: Copernicus – Kepler – Borelli, Ithaca, New York: Cornell University Press. ISBN 0-8014-0504-1.

- Thomas Kuhn (1957). The Copernican Revolution: Planetary Astronomy in the Development of Western Thought, Cambridge: Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-17100-4.

Further reading

- Danielson, Dennis, "The First Copernican: Georg Joachim Rheticus and the Rise of the Copernican Revolution", Walker & Company, 2006, ISBN 0-8027-1530-3

External links

- Primary Sources

- O'Connor, John J.; Robertson, Edmund F., "Nicolaus Copernicus", MacTutor History of Mathematics Archive, University of St Andrews

- Works by Nicolaus Copernicus at Project Gutenberg

- De Revolutionibus, autograph manuscript — Full digital facsimile, Jagiellonian University

- Template:Pl icon Copernicus' letters to various celebrities, among others the King Sigmundus I of Poland

- General

- Copernicus in Torun

- Nicolaus Copernicus Museum in Frombork

- Portraits of Copernicus: Copernicus' face reconstructed; Portrait; Nicolaus Copernicus

- Copernicus and Astrology — Cambridge University: Copernicus had – of course – teachers with astrological activities and his tables were later used by astrologers.

- Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy entry

- Find-A-Grave profile for Nicolaus Copernicus

- 'Body of Copernicus' identified — BBC article including image of Copernicus using facial reconstruction based on located skull

- Copernicus and Astrology

- Nicolaus Copernicus on the 1000 Polish Zloty banknote.

- Parallax and the Earth's orbit [6]

- Copernicus' model for Mars [7]

- Retrograde Motion[8]

- Copernicus'explanation for retrograde motion [9]

- Geometry of Maximum Elongation [10]

- Copernican Model [11]

- About De Revolutionibus

- The Copernican Universe from the De Revolutionibus

- De Revolutionibus, 1543 first edition — Full digital facsimile, Lehigh University

- The front page of the De Revolutionibus

- The text of the De Revolutionibus

- A java applet about Retrograde Motion

- The Antikythera Calculator (Italian and English versions)

- Pastore Giovanni, ANTIKYTHERA E I REGOLI CALCOLATORI, Rome, 2006, privately published

- Legacy

- Template:It icon Copernicus in Bologna — in Italian

- Chasing Copernicus: The Book Nobody Read — Was One of the Greatest Scientific Works Really Ignored? All Things Considered. NPR

- Copernicus and his Revolutions — A detailed critique of the rhetoric of De Revolutionibus

- Article which discusses Copernicus's debt to the Arabic tradition

- German-Polish cooperation

- Template:De iconTemplate:Pl icon German-Polish school project on Copernicus

- Template:De iconTemplate:En iconTemplate:Pl icon Büro Kopernikus - An initiative of German Federal Cultural Foundation

- Template:De iconTemplate:Pl icon German-Polish "Copernicus Prize" awarded to German and Polish scientists (DFG website) (FNP website)