Heparin

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Routes of administration | i.v., s.c. |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status |

|

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | nil |

| Metabolism | hepatic |

| Elimination half-life | 1.5 hrs |

| Excretion | ? |

| Identifiers | |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| DrugBank | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.029.698 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C12H19NO20S3 |

| Molar mass | 12000-15000 g/mol g·mol−1 |

Heparin, a highly sulfated glycosaminoglycan is widely used as an injectable anticoagulant and has the highest negative charge density of any known biological molecule.[1] It can also be used to form an inner anticoagulant surface on various experimental and medical devices such as test tubes and renal dialysis machines. Pharmaceutical grade heparin is commonly derived from mucosal tissues of slaughtered meat animals such as porcine intestine or bovine lung.[2]

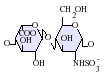

Heparin structure

Native heparin is a polymer with a molecular weight ranging from 3 kDa to 40 kDa although the average molecular weight of most commercial heparin preparations is in the range of 12 kDa to 15 kDa. Heparin is a member of the glycosaminoglycan family of carbohydrates (which includes the closely related molecule heparan sulfate) and consists of a variably sulfated repeating disaccharide unit. The main disaccharide units that occur in heparin are shown below. The most common disaccharide unit is composed of a 2-O-sulfated iduronic acid and 6-O-sulfated, N-sulfated glucosamine, IdoA(2S)-GlcNS(6S). For example this makes up 85% of heparins from beef lung and about 75% of those from porcine intestinal mucosa.[3] Not shown below are the rare disaccharides containing a 3-O-sulfated glucosamine (GlcNS(3S,6S)) or a free amine group (GlcNH3+). Under physiological conditions the ester and amide sulfate groups are deprotonated and attract positively charged counterions to form a heparin salt. It is in this form that heparin is usually administered as an anticoagulant.

1 unit of heparin is the quantity of heparin required to keep 1 mL of cat's blood fluid for 24 hours at 0°C.

-

GlcA-GlcNAc -

GlcA-GlcNS -

IdoA-GlcNS -

IdoA(2S)-GlcNS -

IdoA-GlcNS(6S) -

IdoA(2S)-GlcNS(6S)

Abbreviations

- GlcA = β-D-glucuronic acid

- IdoA = α-L-iduronic acid

- IdoA(2S) = 2-O-sulfo-α-L-iduronic acid

- GlcNAc = 2-deoxy-2-acetamido-α-D-glucopyranosyl

- GlcNS = 2-deoxy-2-sulfamido-α-D-glucopyranosyl

- GlcNS(6S) = 2-deoxy-2-sulfamido-α-D-glucopyranosyl-6-O-sulfate

Three-dimensional structure

The three dimensional structure of heparin is complicated by the fact that iduronic acid may be present in either of two low energy conformations when internally positioned within an oligosaccharide. The conformational equilibrium being influenced by sulfation state of adjacent glucosamine sugars.[4] Nevertheless the solution structure of a heparin dodecasacchride composed solely of six GlcNS(6S)-IdoA(2S) repeat units has been determined using a combination of NMR spectroscopy and molecular modelling techniques.[5] Two models were constructed one in which all IdoA(2S) were in the 2S0 conformation (A and B below) and one in which they are in the 1C4 conformation (C and D below). However there is no evidence to suggest changes between these conformations occurs in a concerted fashion. These models correspond to the protein data bank code 1HPN.

In the image above:

- A = 1HPN (all IdoA(2S) residues in 2S0 conformation) Jmol viewer

- B = van der Waals radius space filling model of A

- C = 1HPN (all IdoA(2S) residues in 1C4 conformation) Jmol viewer

- D = van der Waals radius space filling model of C

In these models heparin adopts a helical conformation, the rotation of which places clusters of sulfate groups at regular intervals of about 17 angstroms (1.7 nm) on either side of the helical axis.

Medical use

Heparin is a naturally occurring anticoagulant produced by basophils and mast cells.[6] Heparin acts as an anticoagulant, preventing the formation of clots and extension of existing clots within the blood. While heparin does not break down clots that have already formed (tissue plasminogen activator will), it allows the body's natural clot lysis mechanisms to work normally to break down clots that have already formed. Heparin is used for anticoagulation for the following conditions:

- Acute coronary syndrome, e.g., myocardial infarction

- Atrial fibrillation

- Deep-vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism

- Cardiopulmonary bypass for heart surgery.

Administration

Details of administration are available in clinical practice guidelines by the American College of Chest Physicians[7]:

Heparin is given parenterally, as it is degraded when taken by mouth. It can be injected intravenously or subcutaneously (under the skin). Intramuscular injections (into muscle) are avoided because of the potential for forming hematomas.

Because of its short biologic half-life of approximately one hour, heparin must be given frequently or as a continuous infusion. However the use of low molecular weight heparin (LMWH) has allowed once daily dosing, thus not requiring a continuous infusion of the drug. If long-term anticoagulation is required, heparin is often only used to commence anticoagulation therapy until the oral anticoagulant warfarin takes effect.

Adverse reactions

A serious side-effect of heparin is heparin-induced thrombocytopenia (HIT syndrome). HITS is caused by an immunological reaction that makes platelets aggregate within the blood vessels, thereby using up coagulation factors. Formation of platelet clots can lead to thrombosis, while the loss of coagulation factors and platelets may result in bleeding. HITS can (rarely) occur shortly after heparin is given, but also when a person has been on heparin for a long while. Immunologic tests are available for the diagnosis of HITS. There is also a benign form of thrombocytopenia associated with early heparin use which resolves without stopping heparin.

Rarer side effects include alopecia and osteoporosis with chronic use.

As with many drugs, overdoses of heparin can be fatal. In September 2006, heparin received worldwide publicity when 3 prematurely-born infants died after they were mistakenly given overdoses of heparin at an Indianapolis hospital.[8]

Treatment of overdose

In case of overdose, protamine sulfate can be given to counteract the action of heparin, in the same amount as heparin.

Mechanism of anticoagulant action

Heparin binds to the enzyme inhibitor antithrombin III (AT-III) causing a conformational change which results in its active site being exposed. The activated AT-III then inactivates thrombin and other proteases involved in blood clotting, most notably factor Xa. The rate of inactivation of these proteases by AT-III increases 1000-fold due to the binding of heparin.[9]

AT-III binds to a specific pentasaccharide sulfation sequence contained within the heparin polymer

GlcNAc/NS(6S)-GlcA-GlcNS(3S,6S)-IdoA(2S)-GlcNS(6S)

The conformational change in AT-III on heparin binding mediates its inhibition of factor Xa. For thrombin inhibition however, thrombin must also bind to the heparin polymer at a site proximal to the pentasaccharide. The highly negative charge density of heparin contributes to its very strong electrostatic interaction with thrombin.[1] The formation of a ternary complex between AT-III, thrombin and heparin results in the inactivation of thrombin. For this reason heparin's activity against thrombin is size dependent, the ternary complex requiring at least 18 saccharide units for efficient formation.[10] In contrast anti factor Xa activity only requires the pentasaccharide binding site.

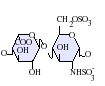

This size difference has led to the development of low molecular weight heparins (LMWHs) and more recently to fondaparinux as pharmaceutical anticoagulants. Low molecular weight heparins and fondaparinux target anti factor Xa activity rather than anti thrombin (IIa) activity, with the aim of facilitating a more subtle regulation of coagulation and an improved therapeutic index. The chemical structure of fondaparinux is shown to the left. This is a synthetic pentasaccharide whose chemical structure is almost identical to the structure the AT-III binding pentasaccharide sequence that can be found within polymeric heparin and heparan sulfate.

With LMWH and fondaparinux, there is a reduced risk of osteoporosis and heparin-induced thrombocytopenia (HIT). Monitoring of the APTT is also not required and indeed does not reflect the anticoagulant effect, as APTT is insensitive to alterations in factor Xa.

Danaparoid, a mixture of heparan sulfate, dermatan sulfate and chondroitin sulfate can be used as an anticoagulant in patients who have developed HIT. Because danaparoid does not contain heparin or heparin fragments cross-reactivity of danaparoid with heparin-induced antibodies is reported as less than 10%.[11]

The effects of heparin are measured in the lab by the partial thromboplastin time (aPTT), (the time it takes the blood plasma to clot).

Heparin's exact physiological role is still unclear, because blood anti-coagulation is mostly achieved by endothelial cell-derived heparan sulfate proteoglycans.[12] Heparin is usually stored within the secretory granules of mast cells and only released into the vasculature at sites of tissue injury. It has been proposed that rather than anticoagulation the main purpose of heparin is in a defensive mechanism at sites of tissue injury against invading bacteria and other foreign materials.[13]

History

Heparin is one of the oldest drugs currently still in widespread clinical use. Its discovery in 1916 predates the establishment of the United States Food and Drug Administration, although it did not enter clinical trials until 1935.[14] It was originally isolated from canine liver cells, hence its name (hepar or "ηπαρ" is Greek for "liver"). Heparin's discovery can be attributed to the research activities of two men, Jay McLean and William Henry Howell.

In 1916 McLean, a second-year medical student at Johns Hopkins University, was working under the guidance of Howell investigating pro-coagulant preparations, when he isolated a fat soluble phosphatide anti-coagulant. It was Howell who coined the term heparin for this type of fat soluble anticoagulant in 1918. In the early 1920s, Howell isolated a water soluble polysaccharide anticoagulant which was also termed heparin, although it was distinct from the phosphatide preparations previously isolated. It is probable that the work of McLean changed the focus of the Howell group to look for anticoagulants, which eventually led to the polysaccharide discovery.

Between 1933 and 1936, Connaught Medical Research Laboratories, then a part of the University of Toronto, perfected a technique for producing safe non-toxic heparin that could be administered to patients in a salt solution. The first human trials of heparin began in May 1935 and by 1937 it was clear that Connaught's heparin was a safe, easily available and effective blood anticoagulant. Prior to 1933, heparin was available, but in small amounts, was extremely expensive, toxic and consequently of no medical value.[15]

For a full discussion of the events surrounding heparin's discovery see Marcum J. (2000).[16]

Novel drug development opportunities for heparin

As detailed in the table below, there is a great deal of potential for the development of heparin like structures as drugs to treat a wide range of diseases in addition to their current use as anticoagulants.[17][18]

| Disease states sensitive to heparin | Heparins effect in experimental models | Clinical status |

| Adult respiratory distress syndrome | Reduces cell activation and accumulation in airways, neutralizes mediators and cytotoxic cell products, and improves lung function in animal models | Controlled clinical trials |

| Allergic encephalomyelitis | Effective in animal models | - |

| Allergic rhinitis | Effects as for adult respiratory distress syndrome, although no specific nasal model has been tested | Controlled clinical trial |

| Arthritis | Inhibits cell accumulation, collagen destruction and angiogenesis | Anecdotal report |

| Asthma | As for adult respiratory distress syndrome, however it has also been shown to improve lung function in experimental models | Controlled clinical trials |

| Cancer | Inhibits tumour growth, metastasis and angiogenesis, and increases survival time in animal models | Several anecdotal reports |

| Delayed type hypersensitivity reactions | Effective in animal models | - |

| Inflammatory bowel disease | Inhibits inflammatory cell transport in general. No specific model tested | Controlled clinical trials |

| Interstitial cystitis | Effective in a human experimental model of interstitial cystitis | Related molecule now used clinically |

| Transplant rejection | Prolongs allograph survival in animal models | - |

- indicates no information available

As a result of heparins effect on such a wide variety of disease states a number of drugs are indeed in development whose molecular structures are identical or similar to those found within parts of the polymeric heparin chain.[17]

| Drug molecule | Effect of new drug compared to heparin | Biological activities |

| Heparin tetrasaccharide | Non-anticoagulant, non-immunogenic, orally active | Anti-allergic |

| Pentosan polysulfate | Plant derived, little anticoagulant activity, Anti-inflammatory, orally active | Anti-inflammatory, anti-adhesive, anti-metastatic |

| Phosphomannopentanose sulfate | Potent inhibitor of heparanase activity | Anti-metastatic, anti-angiogenic, anti-inflammatory |

| Selectively chemically O-desulphated heparin | Lacks anticoagulant activity | Anti-inflammatory, anti-allergic, anti-adhesive |

Evolutionary conservation of heparin

In addition to the bovine and porcine tissue from which pharmaceutical grade heparin is commonly extracted, heparin has also been extracted and characterised from the following species:

- Turkey.[19]

- Whale.[20]

- Dromedary camel.[21]

- Mouse.[22]

- Humans.[23]

- Lobster.[24]

- Fresh water mussel.[25]

- Clam.[26]

- Shrimp.[27]

- Mangrove crab.[28]

- Sand dollar.[28]

The biological activity of heparin within species 6-11 is unclear and further supports the idea that the main physiological role of heparin is not anticoagulation. These species do not possess any blood coagulation system similar to that present within the species listed 1-5. The above list also demonstrates how heparin has been highly evolutionarily conserved with molecules of a similar structure being produced by a broad range of organisms belonging to many different phyla.

Other uses/information

- Heparin gel (topical) may sometimes be used to treat sports injuries. It is known that the diprotonated form of histamine binds site specifically to heparin.[29] The release of histamine from mast cells at a site of tissue injury contributes to an inflammatory response. The rationale behind the use of such topical gels may be to block the activity of released histamine and so help to reduce inflammation.

- Heparin gains the capacity to initiate angiogenesis when its copper salt is formed. Copper free molecules are non-angiogenic.[30][31] In contrast heparin may inhibit angiogenesis when it is administered in the presence of corticosteroids.[32] This anti-angiogenic effect is independent of heparins anticoagulant activity.[33]

- Test tubes, Vacutainers, and capillary tubes that use the lithium salt of heparin (lithium heparin) as an anticoagulant are usually marked with green stickers and green tops. Heparin has the advantage over EDTA as an anticoagulant, as it does not affect levels of most ions. However it has been shown that the levels of ionized calcium may be decreased if the concentration of heparin in the blood specimen is too high.[34] Heparin can interfere with some immunoassays, however. As lithium heparin is usually used, a person's lithium levels cannot be obtained from these tubes; for this purpose, royal-blue topped Vacutainers containing sodium heparin are used.

- Heparin-coated blood oxygenators are available for use in heart-lung machines. Among other things, these specialized oxygenators are thought to improve overall biocompatibility and host homeostasis by providing characteristics similar to native endothelium.

- The DNA binding sites on RNA polymerase can be occupied by heparin, preventing the polymerase binding to promoter DNA. This property is exploited in a range of molecular biological assays.

- Common diagnostic procedures require PCR amplification of a patient's DNA, which is easily extracted from white blood cells treated with heparin. This poses a potential problem, since heparin may be extracted along with the DNA, and it has been found to interfere with the PCR reaction at levels as low as 0.002 U in a 50 μL reaction mixture.[35]

- Immobilized heparin can be used as an affinity ligand in protein purification. In this capacity it can be used in two ways. The first of which is to use heparin to select out specific coagulation factors or other types of heparin binding proteins from a complex mixture of non-heparin binding proteins. Specific proteins can then be selectively dissociated from heparin with the use of differing salt concentrations or by use of a salt gradient. The second use is to use heparin as a high capacity cation exchanger. This use takes advantage of heparins high number of anionic sulfate groups. These groups will capture common cations such as Na+ or Ca2+ in solution.

- Heparin does not break up fibrin, it only prevents conversion of fibrinogen to fibrin. Only thrombolytics can break up a clot.

Popular culture

- Actor Dennis Quaid's twelve day old twins mistakenly were given 1,000 times the requested dosage of heparin in November 2007.[36]

- Heparin was featured in Dan Brown's novel Angels and Demons, where the intentional overdose of the drug was used in the murder of a significant character that was disguised to resemble a death by stroke.

- Was featured in the television show Scrubs. The protagonist (JD) was called in by a new medical student on whether low-molecular weight or unfractionated heparin should be used for a patient. JD replies by saying they're the exact same thing. This is intended as a joke because they are not the same thing!

References

- ^ a b Cox, M. (2004). Lehninger, Principles of Biochemistry. Freeman. p. 1100. ISBN 0-71674339-6.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Linhardt RJ, Gunay NS. (1999). "Production and Chemical Processing of Low Molecular Weight Heparins". Sem. Thromb. Hem. 3: 5–16. PMID 10549711.

- ^ Gatti, G., Casu, B.; et al. (1979). "Studies on the Conformation of Heparin by lH and 13C NMR Spectroscopy" (PDF). Macromolecules. 12 (5): 1001–1007.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Ferro D, Provasoli A; et al. (1990). "Conformer populations of L-iduronic acid residues in glycosaminoglycan sequences". Carbohydr. Res. 195: 157–167. PMID 2331699.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help) - ^ Mulloy B, Forster MJ, Jones C, Davies DB. (1993). "NMR and molecular-modelling studies of the solution conformation of heparin". Biochem. J. 293: 849–858. PMID 8352752.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Guyton, A. C. (2006). Textbook of Medical Physiology. Elsevier Saunders. p. 464. ISBN 0-7216-0240-1.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Hirsh J, Raschke R (2004). "Heparin and low-molecular-weight heparin: the Seventh ACCP Conference on Antithrombotic and Thrombolytic Therapy". Chest. 126 (3 Suppl): 188S–203S. doi:10.1378/chest.126.3_suppl.188S. PMID 15383472.

- ^ Kusmer, Ken (2006-09-20). "3rd Ind. preemie infant dies of overdose". Fox News (Associated Press). Retrieved 2007-01-08.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Bjork I, Lindahl U. (1982). "Mechanism of the anticoagulant action of heparin". Mol. Cell. Biochem. 48: 161–182.

- ^ Petitou M, Herault JP, Bernat A, Driguez PA; et al. (1999). "Synthesis of Thrombin inhibiting Heparin mimetics without side effects". Nature. 398: 417–422. PMID 10201371.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Shalansky, Karen. DANAPAROID (Orgaran®) for Heparin-Induced Thrombocytopenia. Vancouver Hospital & Health Sciences Centre, February 1998 Drug & Therapeutics Newsletter. Retrieved on 2007-01-08.

- ^ Kojima T, Leone CW; et al. (1992). "Isolation and characterisation of heparan sulfate proteoglycans produced by cloned rat microvascular endothelial cells". J. Biol. Chem. 267: 4859–4569. PMID 1537864.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help) - ^ Nader, HB; et al. (1999). "Heparan sulfates and heparins: similar compounds performing the same functions in vertebrates and invertebrates?". Braz. J. Med. Biol. Res. 32 (5): 529–538. PMID 10412563.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help) - ^ Linhardt RJ. (1991). "Heparin: An important drug enters its seventh decade". Chem. Indust. 2: 45–50.

- ^ Rutty, CJ. "Miracle Blood Lubricant: Connaught and the Story of Heparin, 1928-1937". Health Heritage Research Services. Retrieved 2007-05-21.

- ^ Marcum J. (2000). "The origin of the dispute over the discovery of heparin". J. Hist. Med. Allied. Sci. 55: 37–66. PMID 10734720.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|part=ignored (help) - ^ a b Lever R. and Page C.P. (2002). "Novel drug opportunities for heparin". Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 1 (2): 140–148. PMID 12120095.

- ^ Coombe D.R and Kett W.C. (2005). "Heparan sulfate-protein interactions: therapeutic potential through structure-function insights". Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 62 (4): 410–424. PMID 15719168.

- ^ Warda M, Mao W.; et al. (2003). "Turkey intestine as a commercial source of heparin? Comparative structural studies of intestinal avian and mammalian glycosaminoglycans". Comp. Biochem. Physiol. B Biochem. Mol. Biol. 134 (1): 189–197. PMID 12524047.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help) - ^ Ototani N, Kikuchi M, Yosizawa Z. (1981). "Comparative studies on the structures of highly active and relatively inactive forms of whale heparin". J Biochem (Tokyo). 90 (1): 241–246. PMID 7287679.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Warda M, Gouda EM.; et al. (2003). "Isolation and characterization of raw heparin from dromedary intestine: evaluation of a new source of pharmaceutical heparin". Comp. Biochem. Physiol. C Toxicol. Pharmacol. 136 (4): 357–365. PMID 15012907.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help) - ^ Bland CE, Ginsburg H.; et al. (1982). "Mouse heparin proteoglycan. Synthesis by mast cell-fibroblast monolayers during lymphocyte-dependent mast cell proliferation". J. Biol. Chem. 257 (15): 8661–8666. PMID 6807978.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help) - ^ Linhardt RJ, Ampofo SA.; et al. (1992). "Isolation and characterization of human heparin". Biochemistry. 31 (49): 12441–12445. PMID 1463730.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help) - ^ Hovingh P, Linker A. (1982). "An unusual heparan sulfate isolated from lobsters (Homarus americanus)". J. Biol. Chem. 257 (16): 9840–9844. PMID 6213614.

- ^ Hovingh P, Linker A. (1993). "Glycosaminoglycans in Anodonta californiensis, a freshwater mussel". Biol. Bull. 185 (2): 263–276.

- ^ Pejler G, Danielsson A.; et al. (1987). "Structure and antithrombin-binding properties of heparin isolated from the clams Anomalocardia brasiliana and Tivela mactroides". J. Biol. Chem. 262 (24): 11413–11421. PMID 3624220.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help) - ^ Dietrich CP, Paiva JF.; et al. (1999). "Structural features and anticoagulant activities of a novel natural low molecular weight heparin from the shrimp Penaeus brasiliensis". Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1428 (2–3): 273–283. PMID 10434045.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help) - ^ a b Medeiros GF, Mendes, A.; et al. (2000). "Distribution of sulfated glycosaminoglycans in the animal kingdom: widespread occurence of heparin-like compounds in invertebrates". Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1475 (3): 287–294. PMID 10913828.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Chuang W, Christ MD, Peng J, Rabenstein DL. (2000). "An NMR and molecular modeling study of the site specific binding of histamine by heparin, chemically modified heparin and heparin derived oligosacchrides". Biochemistry. 39: 3542–3555. PMID 10736153.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Alessandri, G. Raju, K. and Gullino, PM. (1983). "Mobilization of capillary endothelium in-vitro induced by effectors of angiogenesis in-vivo". Cancer. Res. 43: 1790–1797. PMID 6187439.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Raju, K. Alessandri, G. Ziche, M. and Gullino, PM. (1982). "Ceruloplasmin, copper ions, and angiogenesis". J. Natl. Cancer. Inst. 69: 1183–1188. PMID 6182332.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Folkman J. (1985). "Regulation of angiogenesis: a new function of heparin". Biochem. Pharmacol. 34: 905–909. PMID 2580535.

- ^ Folkman J. and Ingber DE. (1987). "Angiostatic steroids. Method of discovery and mechanism of action". Ann. Surg. 206 (3): 374–383. PMID 2443088.

- ^ Higgins, C. (October 2007). "The use of heparin in preparing samples for blood-gas analysis" (PDF). Medical Laboratory Observer.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: year (link) - ^ Yokota M, Tatsumi N, Nathalang O, Yamada T, Tsuda I. (1999). "Effects of Heparin on Polymerase Chain Reaction for Blood White Cells". J. Clin. Lab. Anal. 13: 133–140. PMID 10323479.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Ornstein, Charles; Gorman, Anna. (November 21, 2007) Los Angeles Times Dennis Quaid's newborns reportedly harmed by medical mix-up. State says it is investigating an incident involving twins at Cedars-Sinai, purportedly involving a medication overdose.

External links