Mandolin

| |

| Classification | |

|---|---|

| Playing range | |

|

(a regularly tuned mandolin with 14 frets to body) | |

| Related instruments | |

| |

A mandolin is a musical instrument which is plucked, strummed or a combination of both. It is descended from the mandora. The most common design as originated in Naples, Italy has eight metal strings in four pairs (courses) which are plucked with a plectrum. Variants include four-string (one string per course), six-string (one string per course) as per the Milanese design, twelve-string (three strings per course), and sixteen-string (four string per course). It has a body with a teardrop-shaped soundtable (i.e. face), or one which is essentially oval in shape, with a soundhole, or soundholes, of varying shapes which are open and not latticed.[1][2]

Mandolin construction

A mandolin's typically hollow wooden body has a neck with a flat (or slightly radiused) fretted fingerboard, a nut and floating bridge, a tailpiece or pinblock at the edge of the face to which the strings are attached, and mechanical tuning machines, rather than friction pegs, to accommodate metal strings. Like the guitar, the mandolin has relatively poor sustain; that is, the sound from a plucked string decays quickly. A note cannot be maintained for an arbitrary length of time as with a bowed note on a violin. Its small size and higher pitch makes this problem more severe than with the guitar, and the use of tremolo (rapid picking of one or more pairs of strings) is often used to create a sustained note or chords. This technique works particularly well with a mandolin's paired strings, where one of the pair is sounding while the other is being struck by the pick, giving a more rounded and continuous sound than is possible with a single coursed instrument.

==Mandolin forms==

Mandolins come in several forms. The Neapolitan style, known as a round-back or bowl-back (or "tater-bug", colloquial American) has a vaulted back made of a number of strips of wood in a bowl formation, similar to a lute, and usually a canted, two-plane, uncarved top. The Portuguese bandolim, a flat-back style, is derived from the cittern, but is tuned the same as most mandolins. Another form has a banjo-style body.

At the very end of the nineteenth century, a new style, with a carved top and back construction inspired by violin family instruments began to supplant the European-style bowl-back instruments, especially in the United States. This new style is credited to mandolins designed and built by Orville Gibson, a Kalamazoo, Michigan luthier who founded the "Gibson Mandolin-Guitar Manufacturing Co., Limited" in 1902. Gibson mandolins evolved into two basic styles: the Florentine or F-style, which has a decorative scroll near the neck, two points on the lower body, and usually a scroll carved into the headstock; and the A-style, which is pear shaped, has no points, and usually has a simpler headstock.

These styles generally have either two f-shaped soundholes like a violin (F-5 and A-5), or an oval sound hole (F-4 and A-4 and lower models) directly under the strings. Much variation exists between makers working from these archetypes, and other variants have become increasingly common. The Gibson F-hole F-5-style mandolins have come to be considered the most typical and traditional for playing American bluegrass music, while the A-style is generally more associated with Irish, folk, or classical music. The more complicated woodwork also translates into a more expensive instrument.

Internal bracing in the F-style mandolins was usually achieved with parallel tone bars, similar to a violin's bassbar. Some makers instead employ "x-bracing" which is simply two tone bars mortised to each other to cross into an X supporting the top. Some luthiers are now using a "modified x-bracing", which incorporates both a tone bar and x-bracing.

Numerous modern mandolin makers build instruments which are largely replicas of the Gibson F-5 Artist models built in the early 1920s by Gibson acoustician Lloyd Loar. Original Loar-signed instruments are sought after and extremely valuable.

Other American-made variants include the Howe-Orme guitar-shaped mandolin (manufactured by the Elias Howe Company between 1897 and roughly 1920), which featured a cylindrical bulge along the top from fingerboard end to tailpiece; the Army-Navy style with a flat back and top; and the Vega mando-lute (more commonly called a cylinder-back mandolin manufactured by the Vega Company between 1913 and roughly 1927), which had a similar longitudinal bulge but on the back rather than the front of the instrument.

As with almost every other contemporary string instrument, another modern variant is the electric mandolin. These mandolins can have four (single), five (single) or eight (double) strings.

Mandolin history

Mandolins evolved from the lute family in Italy during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, and the deep bowled mandolin produced particularly in Naples became a common type in the nineteenth century. The original instrument was the mandore (mandorla is "almond" in Italian, describing the instrument's body shape) and evolved in the fourteenth century from the lute. As time passed and the instrument spread around Europe, it took on many names and various structural characteristics.

Further back, dating to around 15,000 BC to 8,000 BC, single-stringed instruments have been seen in cave paintings and murals. They were struck, plucked, and eventually bowed. From these, the families of stringed instruments developed. Single strings were long and gave a single melody line. To shorten the scale length, other strings were added with a different tension and pitch so one string took over where another left off. In turn, this led to being able to play dyads and chords. The bowed family became the rabob, rebec, and then the fiddle, evolving into the modern violin family by 1520 (incidentally also in Italy). The plucked family led to lute-like instruments in 2000 BC Mesopotamia, and developed into the oud or ud before appearing in Spain, first documented around 711 AD, courtesy of the Moors.

Over the next centuries, frets were added and the strings doubled to courses, leading to the first lute appearing in the thirteenth century. The history of the lute and the mandolin are intertwined from this point. The lute gained a fifth course by the fifteenth century, a sixth a century later, and up to thirteen courses in its heyday. As early as the fourteenth century a miniature lute or mandora appeared. Similar to the mandola, it had counterparts in Assyria (pandura), the Arab countries (dambura), and Ukraine (kobza-bandura). From this, the mandolino (a small gut-strung mandola with six strings tuned g b e' a' d g sometimes called the Baroque mandolin and played with a quill, wooden plectrum or finger-style) was developed in several places in Italy. The mandolino was sometimes called a mandolin in the early eighteenth century (around 1735) Naples. At this point, all such instruments were strung with gut strings.

The first evidence of modern steel-strung mandolins is from literature regarding popular Italian players who traveled through Europe teaching and giving concerts. Notable is Signor Leone and G. B. Gervasio who travelled widely between 1750 and 1810.[2] This, with the records gleaned from the Italian Vinaccia family of luthiers in Naples, Italy, lead some musicologists to believe that the modern steel-strung mandolin was developed in Naples by the Vinaccia family. Gennaro Vinaccia was active circa 1710 to circa 1788, and Antonio Vinaccia was active circa 1734 to circa 1796.[3] An early extant example of a mandolin is one built by Antonio Vinaccia in 1772 which resides at the Victoria and Albert Museum in London, England. Another is by Giuseppe Vinaccia built in 1763, residing at the Kenneth G. Fiske Museum of Musical Instruments in Claremont, California.[4] The earliest extant mandolin was built in 1744 by Gaetano Vinaccia. It resides in the Conservatoire Royal de Musique in Brussels, Belgium.[5]

These early mandolins are termed Neapolitan mandolins, because of their origin from Naples. They are distinguished by an almond-shaped body with a bowled back which is constructed from curved strips of wood along its length. The soundtable is bent just behind the bridge, the bending achieved with a heated bending iron. This "canted" table aids the body to support a greater string tension. A hardwood fingerboard is flush with the soundtable. Ten metal or ivory frets are spaced along the neck in semitones, with additional frets glued upon the soundtable. The strings are brass except for the lowest string course which are gut or metal wound onto gut. The bridge is a movable length of hardwood or ivory placed in front of ivory pins which hold the strings. Wooden tuning pegs are inserted through the back of a flat pegboard. The mandolins have a tortoise shell pickguard below the soundhole under the strings. A quill or shaped piece of tortoise shell is used as a plectrum.[5][6]

Other luthiers who built mandolins included Calace (1863 onwards) in Naples, Luigi Embergher (1856–1943), the Ferrari family (1716 onwards, also originally mandolino makers), and De Santi (1834–1916) in Rome. The Neapolitan style of mandolin construction was adopted and developed by others, notably in Rome, giving two distinct but similar types of mandolin — Neapolitan and Roman.

The twentieth century saw the rise in popularity of the mandolin for Celtic, bluegrass, jazz, and classical styles. Much of the development of the mandolin from Neapolitan bowl-back to the flat-back style (actually, gently rounded and carved like a violin) is attributable to Orville Gibson (1856–1918). See above.

Tuning

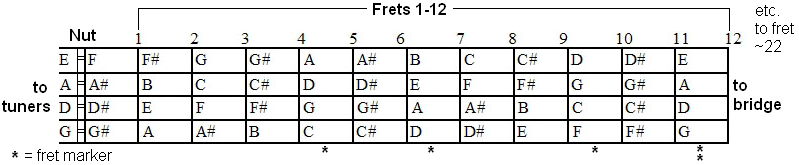

A variety of different tunings are used. Usually, courses of 2 adjacent strings are doubled (tuned to the same pitch). The most common tuning by far (GDAE), is the same as violin tuning:

- fourth (lowest tone) course: G2 (196.00 Hz)

- third course: D3 (293.66 Hz)

- second course: A3 (440.00 Hz; A above middle C)

- first (highest tone) course: E4 (659.25 Hz)

Other tunings exist, including "cross-tunings" in which the usually doubled string runs are tuned to discrete pitches. This is often used in the "cross-picking" style of playing. Additionally, guitarists may sometimes tune a mandolin to mimic a portion of the intervals on a standard guitar tuning to achieve familiar fretting patterns.

Mandolin family

The mandolin is the soprano member of the mandolin family, as the violin is the soprano member of the violin family. Like the violin, its scale length is typically about 13 inches (330 mm). Modern American mandolins modeled after Gibsons have a longer scale, about 13-7/8" (352mm).

Other members of the mandolin family are:

- The mandola (US and Canada), termed the tenor mandola in Europe, which is tuned to a fifth below the mandolin, in the same relationship as that of the viola to the violin. Some also call this instrument the "alto mandola". Its scale length is typically about 16.5 inches (420 mm). It is normally tuned like a viola: C-G-D-A.

- The octave mandolin (US and Canada), termed the octave mandola or mandole in Europe, which is tuned an octave below the mandolin. Its scale length is typically about 20 inches (500 mm), although instruments with scales as short as 17 inches (430 mm) or as long as 21 inches (530 mm) are not unknown.

- The mandocello, which is classically tuned to an octave plus a fifth below the mandolin, in the same relationship as that of the cello to the violin: C-G-D-A. Today, it is not infrequently restrung for octave mandolin tuning or the Irish bouzouki's GDAD. Its scale length is typically about 25 inches (635 mm). A typical violoncello scale is 27" (686mm).

- The Greek laouto is essentially a mandocello, ordinarily tuned D-G-D-A, with half of each pair of the lower two courses being tuned an octave high on a lighter gauge string. The body is a staved bowl, the saddle-less bridge glued to the flat face like most ouds and lutes, with mechanical tuners, steel strings, and tied gut frets. Modern laoutos, as played on Crete, have the entire lower course tuned in octaves as well as being tuned a reentrant octave above the expected D. Its scale length is typically about 28 inches (712mm).

- The mando-bass, has 4 single strings, rather than double courses, and is tuned like a double bass. These were made by the Gibson company in the early twentieth century, but appear to have never been very common. Reportedly, most mandolin orchestras preferred to use the ordinary double bass, rather than a specialised mandolin family instrument. Calace and other Italian makers predating Gibson also made mandolin-basses.

- The piccolo or sopranino mandolin is a rare member of the family, tuned one octave above the tenor mandola and one fourth above the mandolin; the same relation as that of the piccolo or sopranino violin to the violin and viola. One model was manufactured by the Lyon & Healy company under the Leland brand. A handful of contemporary luthiers build piccolo mandolins. Its scale length is typically about 9.5 inches (240 mm).

- The Irish bouzouki is also considered a member of the mandolin family; although derived from the Greek bouzouki, it is constructed like a flat backed mandolin and uses fifth-based tunings (most often GDAD, an octave below the mandolin, sometimes GDAE, ADAD or ADAE) in place of the guitar-like fourths-and-third tunings of the three- and four-course Greek bouzouki. Although the bouzouki's bass course pairs are most often tuned in unison, on some instruments one of each pair is replaced with a lighter string and tuned in octaves, in the fashion of the 12-string guitar. Although occupying the same range as the octave mandolin/octave mandola, the Irish bouzouki is distinguished from the former instrument by its longer scale length, typically from 22 inches (560 mm) to 24 inches (610 mm), although scales as long as 26 inches (660 mm), which is the usual Greek bouzouki scale, are not unknown.

- The modern cittern is also an extension of the mandolin family, being typically a five course (ten string) instrument having a scale length between 20 inches (500 mm) and 22 inches (560 mm). It is most often tuned to either DGDAD or GDADA, and is essentially an octave mandola with a fifth course at either the top or the bottom of its range. Some luthiers, such as Stefan Sobell also refer to the octave mandola or a shorter-scaled Irish bouzouki as a cittern, irrespective of whether it has four or five courses.

- In Indian classical music and Indian light music, the mandolin, which bears little resemblance to the European mandolin, is likely to be tuned to E-B-E-B. As there is no concept of absolute pitch in Indian classical music, any convenient tuning maintaining these relative pitch intervals between the strings can be used. Another prevalent tuning with these intervals is C-G-C-G, which corresponds to Sa-Pa-Sa-Pa in the Indian carnatic classical music style. This tuning corresponds to the way violins are tuned for carnatic classical music.

Mandolin music

Mandolins have a long history, and much early music was written for them. In the first half of the 20th century, they enjoyed a period of great popularity in Europe and the Americas as an easier approach to playing string music. Many professional and amateur mandolin groups and orchestras were formed to play light classical string repertory. Just as this practice was falling into disuse, the mandolin found a new niche in American country, old-time music, bluegrass, and folk music. More recently, the Baroque and Classical mandolin repertory and styles have benefited from the raised awareness of and interest in Early music. Tremolo and fingerpicking methods are used while playing a mandolin.

The United States of America

The mandolin's popularity in the United States was spurred by the success of a group of touring young European musicians known as the Estudiantina Figaro, or in the United States, simply the "Spanish Students." The group landed in the U. S. on January 2, 1880 in New York City, and played in Boston and New York to wildly enthusiastic crowds. Ironically, this ensemble did not play mandolins but rather Bandurrias, which are also small, double-strung instruments resembling the mandolin. The success of the Figaro Spanish Students spawned several groups who imitated their musical style and colorful costumes. In many cases, the players in these new musical ensembles were Italian-born Americans who had brought mandolins from their native land. Thus, the Spanish Student imitators did primarily play mandolins and helped to generate enormous public interest in an instrument which previously was relatively unknown in the United States.

Mandolins were a fad instrument from the turn of the century to the mid-twenties. Instruments were marketed by teacher-dealers, much as the title character in the popular musical The Music Man. Often these teacher-dealers would conduct mandolin orchestras: groups of 4-50 musicians who would play various mandolin family instruments together. One musician and director who made his start with a mandolin orchestra was pioneer African-American composer James Reese Europe. The instrument was primarily used in an ensemble setting well into the 1930s, although the fad died out at the beginning of the 1930s; the famous Lloyd Loar Master Model from Gibson (1923) was designed to boost the flagging interest in mandolin ensembles, with little success. The true destiny of the "Loar" as the defining instrument of bluegrass music didn't appear until Bill Monroe purchased F5 S/N 73987[1] in a Florida barbershop in 1943 and popularized it as his main instrument.

The mandolin orchestras never completely went away, however. In fact, along with all the other musical forms the mandolin is involved with, the mandolin ensemble (groups usually arranged like the string section of a modern symphony orchestra, with first mandolins, second mandolins, mandolas, mandocellos, mando-basses, and guitars, and sometimes supplemented by other instruments) continues to grow in popularity. Since the mid-nineties, several public-school mandolin-based guitar programs have blossomed around the country, including Fretworks Mandolin and Guitar Orchestra, the first of its kind. The national organization which represents these groups is the Classical Mandolin Society of America.

Single mandolins were first used in southern string band music in the 1930s, most notably by brother duets such as the sedate Blue Sky Boys (Bill Bolick and Earl Bolick) and the more hard-driving Monroe Brothers (Bill Monroe and Charlie Monroe). However, the mandolin's modern popularity in country music can be directly traced to one man: Bill Monroe, the father of bluegrass music. After the Monroe Brothers broke up in 1939, Bill Monroe formed his own group, after a brief time called the Blue Grass Boys, and completed the transition of mandolin styles from a "parlor" sound typical of brother duets to the modern "bluegrass" style. He joined the Grand Ole Opry in 1939 and its powerful clear-channel broadcast signal on WSM-AM spread his style throughout the South, directly inspiring many musicians to take up the mandolin. Monroe famously played Gibson F5 mandolin, signed and dated July 9, 1923, by Lloyd Loar, chief acoustic engineer at Gibson. The F5 has since become the most imitated tonally and aesthetically by modern builders. Monroe's style involved playing lead melodies in the style of a fiddler, and also a percussive chording sound referred to as "the chop" for the sound made by the quickly struck and muted strings. He also perfected a sparse, percussive blues style, especially up the neck in keys which had not been used much in country music, notably B and E. He emphasized a powerful, syncopated right hand at the expense of left-hand virtuosity. Monroe's most influential follower of the second generation is Frank Wakefield and nowadays Mike Compton of the Nashville Bluegrass Band and David Long, who often tour as a duet.

The other major original bluegrass stylists, both emerging in the early 1950s and active still, are generally acknowledged to be Jesse McReynolds (of Jim and Jesse) who invented a syncopated banjo-roll style of crosspicking and Bobby Osborne of the Osborne Brothers, who is a master of clarity and sparkling single-note runs. Highly-respected and influential modern bluegrass players include Herschel Sizemore, Doyle Lawson, and the multi-genre Sam Bush, who is equally at home with old-time fiddle tunes, rock, reggae, and jazz. Ronnie McCoury of the Del McCoury Band has won numerous awards for his Monroe-influenced playing. The late John Duffey of the original Country Gentlemen and later the Seldom Scene did much to popularize the bluegrass mandolin among folk and urban audiences, especially on the east coast and in the Washington, D.C. area.

Jethro Burns, best known as half of the comedy duo Homer and Jethro, was also the first important jazz mandolinist. Tiny Moore popularized the mandolin in Western swing music. He initially played an 8-string Gibson but switched after 1952 to a 5-string solidbody electric instrument built by Paul Bigsby. Modern virtuosos David Grisman, Sam Bush, and Mike Marshall, among others, have worked since the early 1970s to demonstrate the mandolin's versatility for all styles of music. Chris Thile of California is the best-known of the younger generation of players; the band Nickel Creek features his virtuoso playing in its blend of traditional and pop styles.

Some rock musicians use mandolins, typically single-stringed electric models rather than double-stringed acoustic mandolins. One example is Tim Brennan of the Irish-American punk rock band Dropkick Murphys. In addition to electric guitar, bass, and drums, the band uses several instruments associated with traditional Celtic music, including mandolin, tin whistle, and Great Highland bagpipes. The band explains that these instruments accentuate the growling sound they favor. Levon Helm of The Band occasionally moved from his drum kit to play mandolin, most notably on 'Evangeline' and 'Rockin' Chair. The 1991 R.E.M. hit "Losing My Religion" also featured a simple mandolin lick played by guitarist Peter Buck, who also played the mandolin in nearly a dozen other songs. Rod Stewart's still-played 1971 hit "Maggie May" features a significant mandolin riff in its motif. Every song on Mark Heard's final album, 1992's Satellite Sky, was written on a mandolin, Heard's antique National Silvo electric mandolin was prominently featured on every track of the recording. Jack White of The White Stripes played mandolin for the film Cold Mountain, and plays mandolin on the song "Little Ghost" on the White Stripes album Get Behind Me Satan; he also plays mandolin on "Prickly Thorn, But Sweetly Worn" on "Icky Thump". David Immerglück of the Counting Crows, Monks of Doom, and Glider is also known to feature the mandolin in many of his recordings, especially those with the Counting Crows. Rock superstar Tommy Shaw of STYX has used the mandolin in the their international hit "Boat on the River" (1979) and on the Shaw/Blades album Influence in the song "Dance with Me". The Country band Sugarland's own Kristian Bush has been known to play the mandolin from time to time. Pop rock band Green Day has used a mandolin in several occasions, especially on their 2000 album, Warning:. Boyd Tinsley, violin player of the Dave Matthews Band has been using an electric mandolin since 2005.

Very rarely mandolins are played with bottlenecks or slides. Sam Bush plays with a slide, mostly on a four string mandolin, Ken Burnett, a northern California mandolin player, uses slide playing frequently while playing with rock/folk bands 2Me and Amee Chapman and the Big Finish.

The United Kingdom

The mandolin has been used extensively in the traditional music of England and Scotland for generations, but the instrument has also found its way into British rock music. The mandolin was used by Vivian Stanshall on Mike Oldfield's album "Tubular Bells". It was used extensively by the British folk-rock band Lindisfarne, who featured two members on the instrument, Ray Jackson and Simon Cowe, and whose "Fog on the Tyne" was the biggest selling UK album of 1971-1972. "Maggie May" by Rod Stewart, which hit No. 1 on both the British charts and the Billboard Hot 100, also featured Jackson's playing. It has also been used by other British rock musicians, including Led Zeppelin, whose bassist John Paul Jones is an accomplished mandolin player and has recorded numerous songs on mandolin including "Going to California" and "That's the Way"; the mandolin part on "The Battle of Evermore" is played by Jimmy Page, who composed the song. Another Led Zeppelin song featuring mandolin is "Hey Hey What Can I Do". Pete Townshend of The Who played mandolin on the track "Mike Post Theme", along with many other tracks on Endless Wire. McGuinness Flint, for whom Benny Gallagher played the mandolin on their most successful single, "When I'm Dead And Gone", is another example. Gallagher was also briefly a member of Ronnie Lane's Slim Chance, and played mandolin on their hit "How Come". One of the more prominent early users of the mandolin in popular music were The Incredible String Band, in which Robin Williamson played the instrument extensively throughout the bands musical career. Ian Anderson of Jethro Tull (band) is a highly accomplished mandolin player, as is his guitarist Martin Barre. The popular song "Please Please Please Let Me Get What I Want" by The Smiths featured a mandolin solo played by Johnny Marr. More recently, the Glasgow-based band Sons and Daughters have featured the mandolin, as played by Ailidh Lennon, on tracks such as "Fight", "Start to End", and "Medicine". British folk-punk icons the Levellers also regularly use the mandolin in their songs. Current bands are also beginning to use the Mandolin and its unique sound - such as South London's Indigo Moss who use it throughout their recordings and live gigs. The mandolin has also recently featured in the playing of Matthew Bellamy in the rock band Muse. It also forms the basis of Paul McCartney's recent hit Dance Tonight.

Ireland

The mandolin is becoming a somewhat more common instrument amongst Irish traditional musicians. Fiddle tunes are readily accessible to the mandolin player because of the equivalent range of the two instruments and the practically identical (allowing for the lack of frets on the fiddle) left hand fingerings.

Although almost any variety of acoustic mandolin might be adequate for Irish traditional music, virtually all Irish players prefer flat-backed instruments with oval sound holes to the Italian-style bowl-back mandolins or the carved-top mandolins with f-holes favoured by bluegrass mandolinists. The former are often too soft-toned to hold their own in a session (as well as having a tendency to not stay in place on the player's lap), whilst the latter tend to sound harsh and overbearing to the traditional ear. Greatly preferred are flat-topped "Irish-style" mandolins (reminiscent of the WWI-era Martin Army-Navy mandolin) and carved (arch) top mandolins with oval soundholes, such as the Gibson A-style of the 1920s. The mandolins built by British luthier Stefan Sobell are perhaps the most highly-prized for Irish traditional music, although many other makers, such as Ireland's Joe Foley, also make well-regarded mandolins.

Noteworthy Irish mandolinists include Andy Irvine (who almost always tunes the E down to D), Mick Moloney, Paul Kelly, and Claudine Langille. John Sheahan and Barney McKenna, fiddle player and tenor banjo player respectively, with The Dubliners are also accomplished Irish mandolin players. The Dubliners 'Live at the Gaiety' DVD features an extensive mandolin duet of a three-tune 'set', two hornpipes and a reel. The instruments used are flat-backed, oval hole examples as described above: in this case made by UK luthier Fylde. The Irish guitarist Rory Gallagher often played the mandolin on stage, and he most famously used it in the song 'Going To My Hometown'.

Continental Europe

An increased interest in bluegrass music, especially in Central European countries such as the Czech Republic and Slovak Republic, has inspired many new mandolin players and builders. These players often mix traditional folk elements with bluegrass.

Brazil

The mandolin (called "bandolim") has a long and rich tradition in Brazilian folk music, especially in the style called choro. The composer and mandolin virtuoso Jacob do Bandolim did much to popularize the instrument through many recordings, and his influence continues to the present day. Some contemporary mandolin players in Brazil include Jacob's disciple Deo Rian, and Hamilton de Holanda (the former, a traditional choro-style player, the latter an eclectic innovator).

The mandolin came into Brazil by way of Portugal. Portuguese music has a long tradition of mandolins and mandolin-like instruments (see, for example, the Portuguese guitar).

The mandolin is used almost exclusively as a melody instrument in Brazilian folk music - the role of chordal accompaniment being taken over by the cavaquinho and nylon-strung violão, or Spanish-style guitar. Its popularity, therefore, has risen and fallen with instrumental folk music styles, especially choro. The later part of the 20th century saw a renaissance of choro in Brazil, and with it, a revival of the country's mandolinistic tradition.

Greece

The mandolin has a long tradition in the Ionian islands (the Eptanese) and Crete. It has long been played in the Aegean islands outside of the control of the Ottoman Empire. It is common to see choirs accompanied by mandolin players (mantolinates) in Ionian islands and especially in the cities of Corfu, Zakynthos (also known as Zante) and Kefalonia. The development of songs for mandolin (kantades) developed during the Venetian rule over Ionia.

On the island of Crete, along with the lyra and the laouto, the mandolin is one of the main instruments used in Cretan Music. It appeared on Crete around the time of the Venetian rule of the island. Different variants of the mandolin, such as the mantola, were used to accompany the lyra, the violin, and the laouto. Stelios Foustalierakis reported that the mandolin and the mpougari were used to accompany the lyra in the beginning of the 20th century in the city of Rethimno. There are also reports that the mandolin was mostly a woman's musical instrument. Nowadays it is played mainly as a solo instrument in personal and family events on the Ionian islands and Crete.

India

Mandolin music was used in the Indian Movies as far back as the 1940's by the Raj Kapoor Studios in movies such as Barsaat, Awara etc. Adoption of the mandolin in Carnatic music is recent and, being essentially a very small electric guitar, the instrument itself bears rather small resemblance to European and American mandolins. U. Srinivas has, over the last couple of decades, made his version of the mandolin very popular in India and abroad. Many adaptations of the instrument have been done to cater to the special needs of Indian Carnatic music.

This type of mandolin is also used in Bhangra, dance music popular in Punjabi culture.

Japan

Mandolin and its families are very popular instruments in Japan. But almost all of them are Neapolitan styles except bluegrass bands, and the plucked strings are mandolin orchestras in old Italian style. Morishige Takei(1890-1949), who studied Italian in The Imperial College Of Language and became the court of the Emperor Hirohito, established the mandolin orchestra in Italian style before World War 2. The militaly government could not persecute Japanese mandolinists by the authority of Takei and Italy as the Axis. But Japanese mandolinists had no fanatic patriotisms like Italian mandolinists, so the Japanese mandolin orchestras continued to perform old Italian works after World War 2, and they are prosperous today.

Western mandolinists love solos, duets, trios, quartets, or concertos performed by few players, but almost all Japanese mandolinists love the orchestras by many players. They desired to increase their members over 40 or 50, and add wind instruments or percussions. Of course, Japanese have a tendency to make group.

Jiro Nakano(1902-2000) arranged many Italian works for regular orchestras or winds composed before World War 2 to add them as new repertoires for mandolin orchestras. They are treated as the works for mandolins in Japan.

After World War 2, characteristic works were composed originally for mandolin orchestras. Seiichi Suzuki(1901-1980) ,who is known as the composer of early Kurosawa films, composed many symphonic poems for mandolin orchestras. His works have quite Japanese atmosphere. Hiroshi Ohguri(1918-1982) was affected by Béla Bartók, so his works are powerful and quite racial. They were representative contemporary Japanese composers and also composed many works out of mandolins. And Yasuo Kuwahara(1946-2003) succeed to their exotic worlds by the German techniques.

Hiroyuki Fujikake(1949- ) introduced swings or counterpoints or the chords from folk guitars to compose new works for mandolin orchestras and caught on Japanese mandolinists. And Yoshinao Kobayashi(1961- ), Hidenori Yoshimizu(1961- ), Hiromitsu Kagajo(1961- ) or many other amateur composers have imitated Fujikake’s way.

It is another trend of Japanese mandolin music to performe the arrangements of famous classic works originally for regular orchestras. Tadashi Hattori(1908- ), Jun Akagi(1919-2007), Takashi Kubota(1942- ) added many arrangements as the new repertoires for mandolin orchestras.

Japanese mandolinists have a tendency to love melodic works mainly performed by trembles, but they are poor at rhythmic works mainly performed by pickings cause of the peculiar condition of Japanese musical educations. Japan adopted the educations of Western music after the Meiji Restoration in 1868. But their government acted the fool to separate songs from musics including dances, and they taught their people only songs as the Western music in schools. It was natural that Japanese loved melodic Italian works but they could not understand rhythmic musics originally from dances. By the way, the notion of harmony in music did not exist in Japan cause of their woody structures. You will find it if you appreciate Kabuki, the Japanese operas.

Mandolin players

Renowned modern mandolinists include Chris Thile, Bill Monroe, Ricky Skaggs, David 'Dawg' Grisman, Mike Marshall, Sam Bush, Yank Rachell, and Tim Ware - all of whom revolutionized the use of the instrument through the incorporation of various styles such as rap, techno, classical, rock and jazz. U. Srinivas (popularly known as mandolin Srinivas) was a child prodigy who plays Indian Classical Music on the mandolin, Patrick Vaillant (head of the "mandolin liberation front" and founder of the Melonious Quartet). Famous electric mandolin players include Canadian Nash the Slash

Popular musicians who play mandolin

- Ian Anderson of Jethro Tull

- Jeff Austin of the Yonder Mountain String Band

- Martin Barre of Jethro Tull

- Kristian Bush of Sugarland

- David Bowie

- Peter Buck of R.E.M.

- Win Butler of Arcade Fire

- Sam Bush

- Mike Campbell of Tom Petty & The Heartbreakers

- Ry Cooder

- Lol Creme of 10cc

- Josh Cunningham of The Waifs

- Steve Earle

- Don Felder of The Eagles

- Rory Gallagher

- David Gilmour of Pink Floyd used one on live versions of "Outside the Wall" with Pink Floyd in 1980 and 1981.

- David Grisman

- Graham Gouldman of 10cc

- George Harrison

- Kevin Hearn of Barenaked Ladies

- Andrew Smith of Indie!GO!

- Levon Helm of The Band

- David Immerglück of the Counting Crows, Monks of Doom, and Glider

- John Paul Jones of Led Zeppelin

- Phil Judd of Split Enz

- Michael Kang of The String Cheese Incident

- Edward Larrikin

- Marit Larsen

- Fábio Machado

- Alex Lifeson of Rush

- Bernie Leadon formerly of The Eagles

- Martie Maguire of The Dixie Chicks

- Daron Malakian of System of a Down

- Johnny Marr of The Smiths

- Mike Marshall

- Paul McCartney

- Ronnie McCoury of The Del McCoury Band

- Colin Meloy of The Decemberists

- Chris Funk of The Decemberists

- Mike Mogis of Bright Eyes

- Nash the Slash

- Jimmy Page of Led Zeppelin

- Ed Robertson of Barenaked Ladies

- Robert Schmidt of Flogging Molly

- Jon Schneck of Relient K

- Tommy Shaw of Styx

- Gilberto Silva

- Ricky Skaggs

- U. Srinivas of Shakti

- Sufjan Stevens

- Marty Stuart

- Fred Tackett of Little Feat

- Chris Thile of Nickel Creek

- Timbaland

- Boyd Tinsley of Dave Matthews Band

- Bruce Watson (guitarist) of Big Country

- Stefan Weinerhall of Falconer

- Jack White of The White Stripes

- B. J. Wilson of Procol Harum

- Nancy Wilson of Heart

- Patrick Wolf

- Zakk Wylde of Black Label Society and Ozzy Osbourne (Used mandolin on "Pride and Glory")

- Steve Van Zandt "Little Steven" of The E Street Band

- Robin Williamson of The Incredible String Band

- Radim Zenkl

See also

Footnotes

- ^ Musical Instruments, A Comprehensive Dictionary, by Sibyl Marcuse (Corrected Edition 1975)

- ^ a b The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians, Second Edition, edited by Stanley Sadie and others (2001)

- ^ Embergher History

- ^ CIMCIM International Directory of Musical Instrument Collections

- ^ a b The Early Mandolin by James Tyler and Paul Sparks (1989)

- ^ The Classical Mandolin by Paul Sparks (1995)

External links

Further reading

CHORD DICTIONARIES

- Richards, Tobe A. (2007). The Mandolin Chord Bible: 2,736 Chords. United Kingdom: Cabot Books. ISBN 978-1-906207-01-4. — A very comprehensive chord dictionary

- Major, James (2002). Mandolin Chord Book. United States: Music Sales Ltd. ISBN 978-0825622960. — A case-style chord dictionary

- Johnson, Chad (2003). Hal Leonard Mandolin Chord Finder. United States: Hal Leonard. ISBN 978-0634054228. — A comprehensive chord dictionary

METHOD & INSTRUCTIONAL GUIDES

- Bay, Mel (1987). Complete Mandolin Method. United States: Mel Bay. ISBN 978-0871667632. — Instructional guide