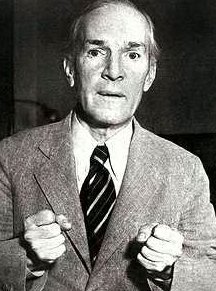

Upton Sinclair

Upton Sinclair | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | September 20, 1878 Baltimore, Maryland |

| Died | November 25, 1968 (aged 90) Bound Brook, New Jersey |

| Occupation | Novelist, writer, journalist, political activist |

| Nationality | |

Upton Beall Sinclair, Jr. (September 20, 1878 – November 25, 1968), was a prolific American author who wrote over 90 books in many genres and was widely considered to be one of the best investigators, advocating socialist views and supporting anarchist causes. He achieved considerable popularity in the first half of the 20th century. He gained particular fame for his 1906 novel The Jungle, which dealt with conditions in the U.S. meat packing industry and caused a public uproar that partly contributed to the passage of the Pure Food and Drug Act and the Meat Inspection Act in 1906.[1]

Biography

He was born in Baltimore, Maryland, the son of Upton Beall Sinclair and Priscilla Harden. His father was a liquor salesman whose alcoholism shadowed his son's childhood. From an early age, Upton had a keen interest in religion and literature. His two great heroes were Jesus Christ and Percy Bysshe Shelley. In 1888, the Sinclair family moved to The Bronx.

Sinclair married his first wife, Meta Fuller, in 1900.

An early success was the Civil War novel Manassas, written in 1903 and published a year later. Originally projected as the opening book of a trilogy, the success of The Jungle caused him to drop his plans, although he did revise Manassas decades later by "moderating some of the exuberance of the earlier version".[citation needed] The Jungle brought to light many major issues in America, such as poverty.

Sinclair created a socialist commune, named Helicon Hall Colony, in 1906 with proceeds from his novel The Jungle. One of those who joined was the novelist and playwright Sinclair Lewis, who worked there as a janitor.

Sinclair made several bids for office. His first was in 1906. The Socialist Party of America sponsored his candidacy for Congress in New Jersey. He lost with just over 3% of the votes.[2][3]

The colony burned down in 1907, apparently from arson. After the famed fire of Helicon Hall, he moved to Arden, Delaware, where many Georgist, Socialist, and Communist "Free Thinkers" lived, including Mother Bloor's son Hamilton "Buzz" Ware. Some say that he worked in a tree house behind his home during these years.

Around 1911, Sinclair's wife ran off with the poet Harry Kemp (later known as the Dunes Poet of Provincetown, Massachusetts). Within a few years, Sinclair moved to Pasadena, California, where he founded the state's chapter of the American Civil Liberties Union in the 1920s. Sinclair went on to run unsuccessfully for Congress twice on the Socialist ticket: in 1920, for the United States House of Representatives, and in 1922, for the Senate.[4]

Sinclair's 1928 book, Boston, created controversy by proclaiming the innocence of Nicola Sacco and Bartolomeo Vanzetti, anarchists who were accused of a murder/robbery in that city. Sinclair faced what he would later call "the most difficult ethical problem of my life," when he was told in confidence by Sacco and Vanzetti's former attorney, Fred Moore, that they were guilty and how their alibis were supposedly arranged.[5] However, in the letter revealing that discussion with Moore, Sinclair also wrote, "I had heard that Moore was using drugs. I knew that he had parted from the defense committee after the bitterest of quarrels... Moore admitted to me that the men themselves, had never admitted their guilt to him."[citation needed] Although the two men were ultimately executed, this episode has been used by some to claim that Sacco and Vanzetti were guilty and that Sinclair knew that when he wrote his novel. However, this account has been disputed by Sinclair biographer Greg Mitchell.[citation needed]

In 1934, Sinclair made his most successful run for office, this time as a Democrat. Sinclair's platform for the California gubernatorial race of 1934, known as EPIC (End Poverty in California), galvanized the support of the Democratic Party, and Sinclair gained its nomination. Conservatives in California were themselves galvanized by this, as they saw it as an attempted communist takeover of their state. They used massive political propaganda portraying Sinclair as a Communist, even as he was being portrayed by American and Soviet communists as a capitalist. Robert A. Heinlein, the science fiction author, was deeply involved in Sinclair's campaign, a point which Heinlein tried to obscure from later biographies, as Heinlein tried to keep his personal politics separate from his public image as an author.[citation needed]

Sinclair was defeated by Frank F. Merriam in the election, and largely abandoned EPIC and politics to return to writing. However, the race of 1934 would become known as the first race to use modern campaign techniques like motion pictures.

Of his gubernatorial bids, Sinclair remarked in 1951: "The American People will take Socialism, but they won't take the label. I certainly proved it in the case of EPIC. Running on the Socialist ticket I got 60,000 votes, and running on the slogan to 'End Poverty in California' I got 879,000. I think we simply have to recognize the fact that our enemies have succeeded in spreading the Big Lie. There is no use attacking it by a front attack, it is much better to out-flank them."[6]

Aside from his political and social writings, Sinclair took an interest in psychic phenomena and experimented with telepathy, writing a book titled "Mental Radio", published in 1930. According to Sinclair, a 34-pound table was once levitated eight feet over his head by a young psychic in a seance.[7][8]

After Sinclair's first wife left, he married Mary Craig Kimbrough (1883 - 1961), a woman who was later tested for psychic abilities. After her death, Sinclair married a third time, to Mary Elizabeth Willis (1882 - 1967). Late in life, he moved from California to Buckeye, Arizona, and then to Bound Brook, New Jersey. Sinclair died in 1968, and is buried in Rock Creek Cemetery in Washington, DC, next to his third wife, who died a year before him.

The Upton Sinclair House in Monrovia, California, is now a National Historic Landmark. The papers, photographs, and first editions of most of his books are found at the Lilly Library at Indiana University in Bloomington, Indiana.[9]

Political and social activism

Sinclair believed that the main point of The Jungle was lost on the public, overshadowed by his descriptions of the unhealthy conditions in packing plants. The public health concerns dealt with in The Jungle were not as significant to Sinclair as the human tragedy lived by his main character and other workers in the plants. His main goal for the book was to demonstrate the inhumane conditions of the wage earner under capitalism, not to inspire public health reforms in how the packing was done. Indeed, Sinclair lamented the effect of his book and the public uproar that resulted: "I aimed at the public's heart, and by accident I hit it in the stomach." Still, the fame and fortune he gained from publishing The Jungle enabled him to write books on almost every issue of social injustice in the Twentieth Century. [1]

Sinclair is well-known for his principle: "It is difficult to get a man to understand something when his salary depends on his not understanding it." This quotation by Sinclair has appeared in many political books, essays, articles, and other forms of media.[citation needed]

The Lanny Budd series

Between 1940 and 1953, Sinclair wrote the World's End series of 11 novels about Lanny Budd, the "red" son of an American arms manufacturer who was a socialite, an art expert and an acquaintance of Hermann Göring and Adolf Hitler.

They cover in sequence much of the political history of the Western world (particularly Europe and America), in the first half of the twentieth century. Almost totally forgotten today, they were all bestsellers upon publication and were published in 21 countries. The third book in the series, Dragon's Teeth, won the Pulitzer Prize in 1943.

Long out of print, the World's End or Lanny Budd series, have recently been re-issued by Simon Publications. For technical reasons, each original volume is issued in two parts, forming a 22-volume set. The series was originally published by Viking Press in New York and T. Werner Laurie in London.

Sinclair in culture

In Sinclair Lewis' novel, It Can't Happen Here, Upton Sinclair is depicted as an eccentric and a supporter of fascism out of opportunistic motives, who is rewarded for his support of an American fascist government by being made ambassador to Great Britain.

Sinclair is extensively featured in Harry Turtledove's American Empire trilogy, in which the American Socialist Party succeeds in becoming a major force in US politics. He wins the 1920 and 1924 presidential elections and becomes the first Socialist President of the United States, his inauguration attended by crowds of jubilant militants waving Red Flags. However, the actual policies which Turtledove attributes to him, once in power, are not particularly radical.[citation needed]

Sinclair is featured as one of the main characters in Chris Bachelder's satirical fictional book, U.S.!: a Novel. Sinclair is literally and repeatedly dug up and resurrected, serving as a personification of the contemporary failings of the American-left and portrayed as a Quixotic reformer attempting to stir an apathetic American public to implement Socialism in America.

Films

Upton Sinclair was the writer or producer of several films, including his involvement, in 1930-32, with Sergei Eisenstein, for Que Viva Mexico!,Charlie Chaplin got him involved in the project.[2]

Sinclair's 1931 novel The Wet Parade was filmed the following year by Victor Fleming, starring Robert Young, Myrna Loy, Walter Huston and Jimmy Durante.

His 1937 novel, The Gnomobile, was the basis of a 1967 Disney musical motion picture, The Gnome-Mobile. [3].

His 1927 novel Oil! was the basis of There Will Be Blood (2007), starring Daniel Day-Lewis and Paul Dano. It was written, produced, and directed by Paul Thomas Anderson. [4]

Works

- Courtmartialed - 1898

- Saved By the Enemy - 1898

- The Fighting Squadron - 1898

- A Prisoner of Morro - 1898

- A Soldier Monk - 1898

- A Gauntlet of Fire - 1899

- Holding the Fort (story) - 1899

- A Soldier's Pledge - 1899

- Wolves of the Navy - 1899

- Springtime and Harvest - 1901

- The Journal of Arthur Stirling - 1903

- Off For West Point - 1903

- From Port to Port - 1903

- On Guard - 1903

- A Strange Cruise - 1903

- The West Point Rivals - 1903

- A West Point Treasure - 1903

- A Cadet's Honor - 1903

- Cliff, the Naval Cadet - 1903

- The Cruise of the Training Ship - 1903

- Prince Hagan - 1903

- Manassas - 1904

- A Captain of Industry - 1906

- The Jungle - 1906

- The Millennium (four-act drama) - 1907

- The Overman - 1907

- The Industrial Republic - 1907

- The Metropolis - 1908

- The Money Changers - 1908

- Samuel The Seeker - 1909

- Good Health and How We Won It - 1909

- The Machine (novel) - 1911

- King Coal - 1917

- The Profits of Religion - 1917

- Jimmie Higgins - 1919

- The Brass Check - 1919

- 100% - The Story of a Patriot - 1920

- Main Street - 1920

- The Spy - 1920

- They Call Me Carpenter - 1922

- The Goose-step A Study of American Education - 1923

- The Millennium (novel form) - 1924

- The Goslings - 1924

- Singing Jailbirds (play in four acts) - 1924

- Mammonart - 1925

- Money Writes! - 1927

- Oil! - 1927

- Boston - 1928

- Mental Radio - 1930

- Roman Holiday - 1931

- The Wet Parade - 1931

- American Outpost - 1932

- Upton Sinclair presents William Fox - 1933

- The Epic Plan for California - 1934

- I, Candidate For Governor: And How I Got Licked - 1935

- Co-op: a Novel of Living Together - 1936

- No Pasaran!: A Novel of the Battle of Madrid - 1937

- The Gnomobile- 1937

- The Flivver King - 1937

- Damaged Goods novel {based on a Eugène Brieux play); basis for 1937 movie from Grand National Pictures

- Little Steel - 1938

- Our Lady - 1938

- Letters to a Millionaire - 1939

- World's End - 1940

- Between Two Worlds - 1941

- Dragon's Teeth - 1942

- Wide Is the Gate - 1943

- The Presidential Agent - 1944

- Dragon Harvest - 1945

- A World to Win - 1946

- A Presidential Mission - 1947

- One Clear Call - 1948

- O Shepherd, Speak! - 1949

- Schenk Stefan! - 1951

- The Return of Lanny Budd - 1953

- The Cup of Fury - 1956

- What Didymus Did - UK 1954 / It Happened to Didymus - US 1958

- The Autobiography of Upton Sinclair - 1962 written with the help of Maeve Elizabeth Flynn III

This list is incomplete; you can help by adding missing items. |

External links

- Works by Upton Sinclair at Project Gutenberg

- Biography on Schoolnet

- Guide to the Upton Sinclair Collection at the Lilly Library, Indiana University

- "The Fictitious Suppression of Upton Sinclair’s The Jungle" by Christopher Phelps in History News network, 6-26-2006

- An article by Sinclair on EPIC at the Museum of the City of San Francisco

- 1992 audio interview of Greg Mitchell, author of The Campaign of the Century: Upton Sinclair's Race for Governor of California and the Birth of Media Politics. Interview by Don Swaim of CBS Radio. RealAudio

- ^ http://www.hsus.org/farm/news/ournews/the_jungle_roar.html

- ^ Upton Sinclair Biography Spartacus Educational

- ^ Blackwell, John 1906: Rumble over The Jungle The Trentonian

- ^ Sinclair, Upton October 13, 1934 End Poverty in California The EPIC Movement The Literary Digest

- ^ January 28, 2006 Novelist's book about murder trial called into question Canadian Broadcasting Corporation

- ^ United States Socialism Spartacus Educational

- ^ Fads and Fallacies: In the Name of Science by Martin Gardner, New American Library, 1986

- ^ Saturday Review, 14 Apr 1956

- ^ See this site for more information.

- 1878 births

- 1968 deaths

- American novelists

- California politicians

- California writers

- City University of New York people

- Columbia University alumni

- Investigative journalists

- Maryland writers

- Members of the Socialist Party of America

- New York writers

- People from Baltimore, Maryland

- People from the San Gabriel Valley

- Pulitzer Prize for the Novel winners