Che Guevara

Template:Infobox revolution biography

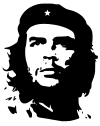

Ernesto Guevara de la Serna (June 14, 1928 – October 9, 1967), commonly known as Che Guevara, el Che, or simply Che; was an Argentinian Marxist revolutionary, political figure, author, military theorist, and leader of Cuban and internationalist guerrillas. His ubiquitous image would also later morph into a countercultural alpha-numeric symbol, utilized by youth and leftist-inspired-movements throughout the world.

As a young medical student, Guevara would embark on a journey throughout Latin America and be transformed by the endemic poverty he witnessed. His experiences and observations during these trips led him to the conclusion that the region's socio-economic inequalities were an insidious result of capitalism, colonialism, neo-colonialism, and imperialism, with the only remedy being World revolution. This belief would lead him to become involved in Guatemala's social revolution under President Jacobo Arbenz Guzmán, whose eventual CIA assisted overthrow, would solidify Guevara’s radical ideology.

Later while in Mexico he would join and be promoted to commander in Fidel Castro’s 26th of July Movement, playing a pivotal role in the successful guerrilla campaign to ultimately seize power from the regime of the US backed Cuban dictator Fulgencio Batista. After the Cuban revolution, Guevara would serve in many prominent governmental positions including President of the National Bank and “supreme prosecutor” over the revolutionary tribunals and executions of suspected war criminals from the previous regime. Along with traveling around the world meeting important leaders on behalf of Cuban socialism, he was also a prolific author of an assortment of books, including a classic manual on the theory and practice of guerrilla warfare. Guevara left Cuba in 1965 to incite revolutions first in an unsuccessful attempt in Congo-Kinshasa and ultimately in Bolivia, where he was captured with help of the CIA and executed.

Both notorious for his disciplined brutality and revered for his unwavering dedication to his revolutionary doctrines, Guevara remains a controversial and respected historical figure. Because of his death, invocation to armed class struggle, and romantic visage; Guevara became an inspirational icon of socialist revolutionary movements worldwide, as well as a global merchandising sensation. He has since been venerated and reviled in dozens of biographies, memoirs, books, essays, documentaries, songs, and films, while being referred to as everything from a "saint" to a "butcher." Time Magazine would profess him to be one of the 100 most influential people of the 20th century,[1] while an Alberto Korda photo of him (shown) has been declared "the most famous photograph in the world."[2]

Early life

Ernesto Guevara de la Serna was born on June 14, 1928 in Rosario, Argentina. The eldest of five children in a family of mixed Spanish and Irish descent; both his father and mother were of Basque ancestry.[Basque] Growing up in a family with leftist leanings, Guevara became known for his radical perspective even as a boy, idolizing Francisco Pizarro while yearning to have been one of his soldiers. Though suffering from the crippling bouts of asthma that were to afflict him throughout his life, he excelled as an athlete. He was an avid rugby union player despite his handicap and earned himself the nickname "Fuser" — a contraction of "El Furibundo" (English: raging) and his mother's surname, "Serna" — for his aggressive style of play. Ernesto was also christened with the nickname "Chancho" (pig) by his schoolmates, because he rarely bathed and wore a "weekly shirt", something he was rather proud of.

Guevara learned chess from his father and began participating in local tournaments by the age of 12. During his adolescence, he became passionate about poetry, especially that of Pablo Neruda, John Keats, and Sara De Ibáñez. It is also said that he memorized Kipling's "If" by heart. The Guevara home contained more than 3,000 books which allowed Guevara to be an enthusiastic and eclectic reader, with interests comprising of Aristotle, Kant, Marx, Gide and Faulkner. He also enjoyed adventure classics by Jack London, Emilio Salgari, and Jules Verne as well as essays by Sigmund Freud and Bertrand Russell.

In 1948 Guevara entered the University of Buenos Aires to study medicine and fell in love with 16-year-old Maria del Carmen Ferreyra.[3] In 1951, Guevara took a year off from his medical studies to embark on a trip traversing South America with his friend, Alberto Granado on a motorcycle to spend a few weeks volunteering at the San Pablo Leper colony in Peru on the banks of the Amazon River. Guevara took notes during this trip and wrote an account using extracts from his notes entitled The Motorcycle Diaries.

Witnessing the widespread poverty, oppression and disenfranchisement throughout Latin America, and influenced by his readings of Marxist literature, Guevara began to view armed revolution as the solution to social inequality. By trips end, he also viewed Latin America not as separate nations, but as a single entity requiring a continent-wide liberation strategy. His conception of a borderless, united Hispanic America sharing a common 'mestizo' culture[Hispanic America] was a theme that would prominently recur during his later revolutionary activities. Upon returning to Argentina, he completed his medical studies and received the diploma accrediting him as a medic on 12 June 1953.[Diploma]

Guatemala

On 7 July 1953, Guevara set out on a trip through Bolivia, Peru, Ecuador, Panama, Costa Rica, Nicaragua, Honduras and El Salvador. In December 1953 he arrived in Guatemala where President Jacobo Arbenz Guzmán headed a democratically elected government that, through land reform and other initiatives, was attempting to end the U.S.-dominated latifundia system. Guevara decided to settle down in Guatemala so as to perfect himself and do what was necessary to become a true revolutionary.[4]

In Guatemala City, Guevara sought out Hilda Gadea Acosta, a Peruvian economist who was well-connected politically as a member of the socialist American Popular Revolutionary Alliance (APRA) led by Víctor Raúl Haya de la Torre. She introduced Guevara to a number of high-level officials in the Arbenz government. Guevara also established contact with a group of Cuban exiles linked to Fidel Castro through the revolutionary attack on the Moncada Barracks in Santiago de Cuba.[5] During this period he acquired his famous nickname, "Che", due to his frequent use of the Argentine interjection Che (IPA: [tʃe]), which is used in much the same way as "hey", "pal", "eh", or "mate"; and employed colloquially now in various English-speaking countries.

Guevara's attempts to obtain a medical internship were unsuccessful and his economic situation was often precarious. He kept away from any political organization, even though his political thinking at the time was clearly sympathetic toward Marxism. On May 15, 1954 a shipment of Škoda infantry and light artillery weapons were sent from Communist Czechoslovakia for the Arbenz Government and arrived in Puerto Barrios.[6][7] prompting a CIA-sponsored coup attempt.[6] Guevara was eager to fight on behalf of Arbenz and joined an armed militia organized by the Communist Youth for that purpose, but frustrated with the group's inaction, he soon returned to medical duties. Following the coup, he again volunteered to fight but soon after Arbenz took refuge in the Mexican Embassy and told his foreign supporters to leave the country. After Hilda Gadea was arrested, Guevara sought protection inside the Argentine consulate where he remained until he received a safe-conduct pass some weeks later and made his way to Mexico.[8]

The overthrow of the Arbenz regime by a coup d'état backed by the Central Intelligence Agency cemented Guevara's view of the United States as an imperialist power that would oppose and attempt to destroy any government that sought to redress the socioeconomic inequality endemic to Latin America and other developing countries. This strengthened his conviction that Marxism achieved through armed struggle and defended by an armed populace was the only way to rectify such conditions.

Cuba

Guevara arrived in Mexico City in early September 1954, and renewed his friendship with the other Cuban exiles whom he had known in Guatemala. In June 1955, López introduced him to Raúl Castro who later introduced him to his older brother, Fidel Castro, the revolutionary leader who had formed the 26th of July Movement and was now plotting to overthrow the dictatorship of Fulgencio Batista in what became the Cuban Revolution. Guevara recognized at once that Castro was the cause for which he had been searching.

Although he planned to be the group's medic, Guevara participated in the military training with the members of the Movement, and at the end of the course, was called "the best guerrilla of them all" by their instructor, Colonel Alberto Bayo.[9] The first step in Castro's revolutionary plan was an assault on Cuba from Mexico via the Granma an old, leaky cabin cruiser. They set out for Cuba on November 25, 1956. Attacked by Batista's military soon after landing, most of the 82 men were killed or executed upon capture. Guevara wrote that it was during this bloody confrontation that he laid down his medical supplies and picked up a box of ammunition dropped by a fleeing comrade, finalizing his symbolic transition from physician to combatant.

Only a small band of revolutionaries survived to re-group as a bedraggled fighting force deep into the Sierra Maestra mountains, where they received support from Frank País's urban guerrilla network, the 26th of July Movement, and local country folk. With Castro and his men withdrawn to the Sierra, the world wondered whether he was alive or dead until the famous Herbert Matthews interview with Castro appeared in the New York Times in early 1957, presenting a lasting, almost mythical image for Castro. Guevara was not present for that interview, but in the coming months he began to realize the importance of the interview that created an icon of a bearded Castro dressed in fatigues, legitimizing the Cuban Revolution. Meanwhile, as supplies and morale grew low, Che considered this "the most painful days of the war."[10]

At this point Castro unexpectedly promoted Che to comandante of a second army column. As Che considered his tactics, he imposed even more ruthless treatment as a strict disciplinarian whose harsh methods were already notorious among the rebel fighters. Deserters were severely punished as traitors, and Guevara was known to send execution squads to hunt down deserters seeking to escape.[11] Che's next plan to hit an enemy garrison did not go as planned and Che, in fear and about to flee, almost shot one of his own sentries. Although the garrison eventually surrendered, Che had already run away. Back in their camp they learn of the murder of Frank Paiz, coordinator for the Oriente, which resulted in demonstrations and strikes across Cuba.

Che became feared for his brutality and ruthlessness.[12] During the guerrilla campaign, he was responsible for the execution of a number of men accused of being informers, deserters or spies.[13] As the war extended, Guevara led a new column of fighters dispatched westward for the final push towards Havana. In the closing days of December 1958, he directed his "suicide squad" in the attack on Santa Clara that became one of the decisive events of the revolution.[14][15][16] Batista, upon learning that his generals were negotiating a separate peace with the rebel leader, fled to the Dominican Republic on January 1, 1959.

On January 8, 1959, Castro's army rolled victoriously into Havana.[17] On February 7, 1959, the government proclaimed Guevara "a Cuban citizen by birth" in recognition of his role in the triumph of the revolutionary forces. Shortly thereafter, he divorced Hilda Gadea, who was still in Mexico. On June 2, 1959, he married Aleida March,[Children] a Cuban-born member of the 26th of July movement with whom he had been living since late 1958.

During the rebellion against Batista's dictatorship, the general command of the rebel army, led by Fidel Castro, introduced into the liberated territories the 19th-century penal law commonly known as the [Ley de la Sierra]. This law included the death penalty for extremely serious crimes, whether perpetrated by the dictatorship or by supporters of the revolution. In 1959, the revolutionary government extended its application to the whole of the republic and to war criminals captured and tried after the revolution. This latter extension, supported by the majority of the population, followed the same procedure as those seen in the Nuremberg Trials held by the Allies after World War II.[18] To implement this plan, Castro named Guevara commander of the La Cabaña Fortress prison, for a five-month tenure (January 2 through June 12, 1959).[19] Guevara was charged with purging the Batista army and consolidating victory by exacting "revolutionary justice" against traitors, chivatos, and Batista's war criminals.[20] Serving in the post as "supreme prosecutor" on the appellate bench, Guevara oversaw the trials and executions of those convicted by revolutionary tribunal. The justification for the execution of torturers and other brutal criminals of the Batista regime, was done under the hope of preventing the people themselves from taking justice into their own hands, as happened during the anti-Machado rebellion, which threw the society into chaos.[21] It is estimated that a few hundred people were executed on Guevara's extra-judicial orders during this time.[22]

On 12 June 1959, as soon as Guevara returned to Havana, Castro sent him out on a three-month tour of fourteen countries, most of them Bandung Pact members in Africa and Asia. Sending Che from Havana allowed Castro to appear to be distancing himself from Che and his Communism, that troubled both the United States and Castro's M-26-7 members.[23] He spent twelve days in Japan (15 - 27 July), participating in negotiations aimed at expanding Cuba's trade relations with that nation but the Japanese were noncommittal. When he returned to Cuba in September 1959, he found Castro now had more political power. The government had begun land seizures included in the agrarian reform law, but was backing off on the compensation offers to landowners, alerting the United States who was becoming wary. The popular leader, Huber Matos, had joined the resisters, acting as the chief spokesman for the M-26-7. Castro began cleaning house with a show down with Matos.[24] Abruptly, Castro appointed Guevara chief official at the National Institute of Agrarian Reform,[INRA], and President of the National Bank of Cuba.[BNC] while allowing him to retain his military rank. Although seeming to be a strange choice for the important position, Che had been promoting the creation of self-sufficient industries since days of the Sierra Maestra. Che was expecting the U.S. to invade and the Cuban population would have to leave the cities and fight as guerillas, although Che's hopes for armed uprisings elsewhere were failing.[25]

In 1960 Guevara provided first aid to victims when the freighter La Coubre, a French vessel carrying munitions from the port of Antwerp, exploded twice while it was being unloaded in Havana harbor, resulting in well over a hundred dead.[26] It was at the memorial service for the victims of this explosion that Alberto Korda took the most famous photograph of him.

Guevara later served as Minister of Industries, a post in which he helped formulate Cuban socialism, and became one of the country's most prominent figures. He called for the diversification of the Cuban economy, and for the elimination of material incentives. He believed that volunteer work and dedication of workers would drive economic growth and all that was needed was will. To display this Guevara led by example, working endlessly at his ministry job, in construction, and even cutting sugar cane as did Castro.[27] During this time he also wrote several publications advocating a replication of the Cuban revolutionary model, promoting small rural guerrilla groups (foco theory) as an alternative to massive armed insurrection.

Guevara did not participate in the fighting of the 1961 Bay of Pigs Invasion, having been ordered by Castro to a command post in Cuba's western Pinar del Río province where he fended off a decoy force. He suffered a bullet wound to the face during this deployment, saying that it had been caused by the accidental discharge of his own gun.[9] Guevara played a key role in bringing to Cuba the Soviet nuclear-armed ballistic missiles that precipitated the Cuban Missile Crisis in October 1962. During an interview with the British newspaper Daily Worker some weeks later, he stated that, if the missiles had been under Cuban control, they would have fired them against major U.S. cities.[28]

Disappearance from Cuba

(New York City - 11 December 1964).

In December 1964 Che Guevara traveled to New York City as head of the Cuban delegation to speak at the UN (listen, requires RealPlayer; or read). He also appeared on the CBS Sunday news program Face the Nation[citation needed] and met with a gamut of people and groups including U.S. Senator Eugene McCarthy,[citation needed] several associates of Malcolm X,[citation needed] and Canadian radical Michelle Duclos. On 17 December, he flew to Paris and embarked on a three-month international tour during which he visited the People's Republic of China, the United Arab Republic (Egypt), Algeria, Ghana, Guinea, Mali, Dahomey, Congo-Brazzaville and Tanzania, with stops in Ireland, Paris and Prague. In Algiers on 24 February, 1965, he made what turned out to be his last public appearance on the international stage when he delivered a speech at an economic seminar on Afro-Asian solidarity.[30][31] He specified the moral duty of the socialist countries, accusing them of tacit complicity with the exploiting Western countries. He proceeded to outline a number of measures which he said the communist-bloc countries must implement in order to accomplish the defeat of imperialism.[32][33] He returned to Cuba on 14 March to a solemn reception by Fidel and Raúl Castro, Osvaldo Dorticós and Carlos Rafael Rodríguez at the Havana airport.

Two weeks later, in 1965 Guevara dropped out of public life and then vanished altogether, his whereabouts were a great mystery in Cuba as he was generally regarded as second in power to Castro himself. His disappearance was variously attributed to the failure of the industrialization scheme he had advocated while minister of industry, to pressure exerted on Castro by Soviet officials disapproving of Guevara's pro-Chinese Communist stance on the Sino-Soviet split, and to serious differences between Guevara and the pragmatic Castro regarding Cuba's economic development and ideological line. Castro had grown increasingly wary of Guevara's popularity and considered him a potential threat. Castro's critics sometimes say his explanations for Guevara's disappearance have always been suspect.

The coincidence of Guevara's views with those expounded by the Chinese Communist leadership was increasingly problematic for Cuba as the nation's economy became more and more dependent on the Soviet Union. Since the early days of the Cuban revolution, Guevara had been considered by many an advocate of Maoist strategy in Latin America and the originator of a plan for the rapid industrialization of Cuba which was frequently compared to China's "Great Leap Forward". According to Western observers of the Cuban situation, the fact that Guevara was opposed to Soviet conditions and recommendations that Castro pragmatically saw as necessary, might also have been the reason for his disappearance. However, both Guevara and Castro were supportive publicly on the idea of a united front.

Following the Cuban Missile Crisis and what Guevara perceived as a Soviet betrayal of Cuba when Castro convinced Khrushchev to withdraw the missiles from Cuban territory, Guevara had grown more skeptical of the Soviet Union. As revealed in his last speech in Algiers, he had come to view the Northern Hemisphere, led by the U.S. in the West and the Soviet Union in the East, as the exploiter of the Southern Hemisphere. He strongly supported Communist North Vietnam in the Vietnam War, and urged the peoples of other developing countries to take up arms and create "many Vietnams".[34]

Pressed by international speculation regarding Guevara's fate, Castro stated on 16 June, 1965, that the people would be informed about Guevara when Guevara himself wished to let them know. Numerous rumors about his disappearance spread both inside and outside Cuba. On 3 October of that year, Castro revealed an undated letter purportedly written to him by Guevara some months earlier in which Guevara reaffirmed his enduring solidarity with the Cuban Revolution but declared his intention to leave Cuba to fight abroad for the revolutionary cause, resigning from all his positions in the government, the party, and renouncing his honorary Cuban citizenship.[35] Guevara's fate remained a mystery at the end of 1965 and his movements and whereabouts continued to be a closely held secret for the next two years.

Congo

In 1965, Guevara decided to venture to Africa and offer his knowledge and experience as a guerrilla to the ongoing war in the Congo. According to Ahmed Ben Bella who was president of Algeria at the time and who talked with Guevara, Che thought that Africa was imperialism's weak link and therefore had enormous revolutionary potential.[36][37] He lead the Cuban operation into the Congo in support of the pro-Patrice Lumumba Marxist Simba movement in the Congo-Kinshasa (currently the Democratic Republic of the Congo). Guevara, his second-in-command Victor Dreke, and twelve other Cuban expeditionaries arrived in the Congo on 24 April 1965 with a contingent of approximately 100 Afro-Cubans joining them soon afterward.[38][39] They collaborated for a time with guerrilla leader Laurent-Désiré Kabila,[Kabila] who helped Lumumba supporters lead a revolt that was suppressed in November of that same year by the Congolese army. Guevara dismissed Kabila as insignificant. "Nothing leads me to believe he is the man of the hour," Guevara wrote.[40]

South African mercenaries including Mike Hoare and Cuban exiles worked with the Congolese army to thwart Guevara. They were able to monitor his communications, arrange to ambush the rebels and the Cubans whenever they attempted to attack, and interdict his supply lines. Despite the fact that Guevara sought to conceal his presence in the Congo, the U.S. government was aware of his location and activities: The National Security Agency (NSA) was intercepting all of his incoming and outgoing transmissions via equipment aboard the USNS Valdez, a floating listening post which continuously cruised the Indian Ocean off Dar-es-Salaam for that purpose.[NSA]

Guevara's aim was to export the Cuban Revolution by instructing local Simba fighters in communist ideology and foco theory strategies of guerrilla warfare. In his Congo Diary, he cites the incompetence, intransigence and infighting of the local Congolese forces as key reasons for the revolt's failure.[41] Later that year, ill with dysentery, suffering from asthma, and disheartened after seven months of frustrations, Guevara left the Congo with the Cuban survivors (six members of his column had died). At one point Guevara considered sending the wounded back to Cuba, then standing alone and fighting until the end in the Congo as a revolutionary example; however, after being urged by his comrades and pressed by two emissaries sent by Castro, at the last moment he reluctantly agreed to leave the Congo. A few weeks later, writing the preface to the diary he kept during the Congo venture, he began: "This is the history of a failure."[42]

Because Castro had made public Guevara's "farewell letter" to him — a letter Guevara had intended should only be revealed in case of his death — wherein he had written that he was severing all ties to Cuba in order to devote himself to revolutionary activities in other parts of the world, he felt he could not return to Cuba with the surviving combatants for moral reasons,[43] and he spent the next six months living clandestinely in Dar-es-Salaam, and Prague. During this time he compiled his memoirs of the Congo experience, and wrote drafts of two more books, one on philosophy[44] and the other on economics.[45] He also visited several countries in Western Europe to test a new false identity and the corresponding documentation (passport, etc.) created for him by Cuban Intelligence that he planned to use to travel to South America. Throughout this period Castro continued to importune him to return to Cuba, but Guevara only agreed to do so when it was understood he would be there only for the few months needed to prepare a revolutionary effort somewhere in Latin America, and that his presence on the island would be secret.

Bolivia

Guevara's location was still unknown. Representatives of the independence movement of Mozambique, the FRELIMO, reported that they met with Guevara in late 1966 or early 1967 in Dar es Salaam regarding his offer to aid in their revolutionary project which they ultimately rejected.[46] In a speech at the 1967 May Day rally in Havana, the Acting Minister of the armed forces, Major Juan Almeida, announced that Guevara was "serving the revolution somewhere in Latin America". The persistent reports that he was leading the guerrillas in Bolivia were eventually shown to be true.

At Castro's behest, a parcel of jungle land in the remote Ñancahuazú region had been purchased by native Bolivian Communists for Guevara to use as a training area and base camp.

Training at this camp in the Ñancahuazú valley proved to be more hazardous than combat to Guevara and the Cubans accompanying him. Little was accomplished in the way of building a guerrilla army. Former Stasi operative Haydée Tamara Bunke Bider, better known by her nom de guerre "Tania", who had been installed as his primary agent in La Paz, was reportedly also working for the KGB and is widely inferred to have unwittingly served Soviet interests by leading Bolivian authorities to Guevara's trail.[47][48]

Guevara's guerrilla force, numbering about 50 and operating as the ELN (Ejército de Liberación Nacional de Bolivia; English: "National Liberation Army of Bolivia"), was well equipped and scored a number of early successes against Bolivian regulars in the difficult terrain of the mountainous Camiri region. In September, however, the Army managed to eliminate two guerrilla groups in a violent battle, reportedly killing one of the leaders.

Guevara's plan for fomenting revolution in Bolivia appears to have been unsuccessful because it was based upon three primary misconceptions:

- He had expected to deal only with the country's military government and its poorly trained and equipped army. However, Guevara was unaware that the U.S. government had sent the CIA and other operatives into Bolivia to aid the anti-insurrection effort. The Bolivian Army was trained and supplied by U.S. Army Special Forces[USMilitary] advisors, including a recently organized elite battalion of Rangers trained in jungle warfare that set up camp in La Esperanza, a small settlement close to the location of Guevara's guerillas.[49][50]

- Guevara had expected assistance and cooperation from the local dissidents which he did not receive, nor did he receive support from Bolivia's Communist Party, under the leadership of Mario Monje which was oriented toward Moscow rather than Havana.

- He had expected to remain in radio contact with Havana. However, the two shortwave transmitters provided to him by Cuba were faulty; the guerrillas were unable to communicate with Havana and Guevara was therefore on his own, receiving no support from Cuba.

In addition, his known preference for confrontation rather than compromise, which had previously surfaced during his guerrilla warfare campaign in Cuba, contributed to his inability to develop successful working relationships with local leaders in Bolivia, just as it had in the Congo.[51] This tendency had existed in Cuba, but had been kept in check by the timely interventions and guidance of Fidel Castro.[52]

Capture and execution

The hunt for Guevara in Bolivia was headed by Félix Rodríguez, a CIA operative.[53][54] On 7 October, an informant apprised the Bolivian Special Forces of the location of Guevara's guerrilla encampment in the Yuro ravine. They encircled the area, and Guevara was wounded and taken prisoner while leading a detachment with Simeón Cuba Sarabia. According to some soldiers present at the capture, as they approached Guevara during the skirmish he allegedly shouted, "Do not shoot! I am Che Guevara and worth more to you alive than dead."[55]

Guevara was taken to a dilapidated schoolhouse in the nearby village of La Higuera. Early the next day, Barrientos ordered that he be killed.[Barrientos] The executioner was Mario Terán, a sergeant in the Bolivian army who had drawn a short straw after arguments over who would get the honor of shooting Guevara broke out among the soldiers. To make the bullet wounds appear consistent with the story the government planned to release to the public, Félix Rodríguez ordered Terán to aim carefully to make it appear that Guevara had been killed in action during a clash with the Bolivian army.[56]

Moments before Guevara was executed he was asked if he was thinking about his own immortality. "No," he replied, "I'm thinking about the immortality of the revolution."[57] Che Guevara also allegedly said to his executioner, "Shoot, coward, you are only going to kill a man."[58] According to Felix Rodriquez the shots that killed Guevara rang out at about 1:10 pm. Guevara received many wounds to the legs and a fatal one to the chest but none to the face that would soon be seen around the world. His body was lashed to the landing skids of a helicopter and flown to neighboring Vallegrande where photographs were taken showing a figure described by some as "Christ-like" lying on a concrete slab in the laundry room of the Nuestra Señora de Malta hospital.[59][60]

A declassified memorandum dated 11 October 1967 to President Lyndon B. Johnson from his senior adviser, Walt Rostow, called the decision to kill Guevara “stupid” but “understandable from a Bolivian standpoint.”[61] After the execution, Rodríguez took personal items of Guevara's including a Rolex watch, often showing them to reporters during the ensuing years. Today, some of these belongings, including his flashlight are on display at the CIA.[62] After a military doctor amputated his hands, Bolivian army officers transferred Guevara's cadaver to an undisclosed location and refused to reveal whether his remains had been buried or cremated.[Amputation] On October 15, Castro acknowledged that Guevara was dead and proclaimed three days of public mourning throughout Cuba. The death of Guevara was regarded as a blow to socialist revolutionary movements in Latin America and the rest of the third world.[citation needed]

While researching his definitive biography Che Guevara: A Revolutionary Life, author Jon Lee Anderson happened to discover the location of Guevara's burial. Thus in 1997, the skeletal remains of a handless body were exhumed from beneath an air strip near Vallegrande, identified as those of Guevara by a Cuban forensic team at the scene, and returned to Cuba. On 17 October, 1997, his remains, with those of six of his fellow combatants, were laid to rest with military honors in a specially built mausoleum[Mausoleum] in the city of Santa Clara, where he had won the decisive battle of the Cuban Revolution.

Also removed when Guevara was captured was his diary, which documented events of the guerrilla campaign in Bolivia.[63] The first entry is on November 7 1966 shortly after his arrival at the farm in Ñancahuazú, and the last entry is on October 7 1967, the day before his capture. The diary tells how the guerrillas were forced to begin operations prematurely due to discovery by the Bolivian Army, explains Guevara's decision to divide the column into two units that were subsequently unable to re-establish contact, and describes their overall unsuccessful venture. It also records the rift between Guevara and the Bolivian Communist Party that resulted in Guevara having significantly fewer soldiers than originally anticipated and shows that Guevara had a great deal of difficulty recruiting from the local populace, due in part to the fact that the guerrilla group had learned Quechua unaware that the local language which was actually Tupí-Guaraní. As the campaign drew to an unexpected close, Guevara became increasingly ill. He suffered from ever-worsening bouts of asthma, and most of his last offensives were carried out in an attempt to obtain medicine.

The Bolivian Diary was quickly and crudely translated by Ramparts magazine and circulated around the world. There are at least four additional diaries in existence — those of Israel Reyes Zayas (Alias "Braulio"), Harry Villegas Tamayo ("Pombo"), Eliseo Reyes Rodriguez ("Rolando")[64] and Dariel Alarcón Ramírez ("Benigno")[65] — each of which reveals additional aspects of the events in question.

Legacy

Some view Che Guevara as a hero. Nelson Mandela, for example, referred to him as: "An inspiration for every human being who loves freedom" and Jean-Paul Sartre, described him as "Not only an intellectual but also the most complete human being of our age."[66] Guevara also remains a beloved national hero in Cuba,[67] despite the fact that with his death, Cuba abandoned guerrilla warfare as an instrument of foreign policy.[68]

Conversely, others view him as a spokesman for a failed ideology and as a ruthless executioner. Johann Hari, for example, wrote that "...Che Guevara is not a free-floating icon of rebellion. He was an actual person who supported an actual system of tyranny."[69] Detractors have also theorized that in much of Latin America, Che-inspired revolutions had the practical result of reinforcing brutal militarism for many years.[70] He remains as roundly hated in the Cuban-American community as he is beloved in Cuba.[71][72]

A monochrome graphic of a photograph of Guevara taken by photographer Alberto Korda became one of the century's most ubiquitous images.[73] Guevara remains an iconic figure, both in specifically political contexts[74][75] and as a popular icon of youthful rebellion.[76]

Timeline

Guevara's authored books

- In English

- Argentine, by Ernesto Guevara, Ocean Press (AU), 2008, ISBN 1920888934

- A song written by Che for Fidel Castro (flyer), by Ernesto Guevara, FreeThought Publications, 2000, ASIN B0006RP426

- Back on the Road: A Journey Through Latin America, by Ernesto "Che" Guevara & Alberto Granado, Grove Press, 2002, ISBN 0802139426

- Che Guevara, Cuba, and the Road to Socialism, by Ernesto Guevara, Pathfinder Press, 1991, ISBN 0873486439

- Che Guevara on Global Justice, by Ernesto Guevara, Ocean Press (AU), 2002, ISBN 1876175451

- Che Guevara: Radical Writings on Guerrilla Warfare, Politics and Revolution, by Ernesto Che Guevara, Filiquarian Publishing, 2006, ISBN 1599869993

- Che Guevara Speaks: Selected Speeches and Writings, by Ernesto Guevara, Pathfinder Press (NY), 1980, ISBN 0873486021

- Che Guevara Talks to Young People, by Ernesto Guevara, Pathfinder, (2000), ISBN 087348911X

- Che: The Photobiography of Che Guevara, Thunder's Mouth Press, 1998, ISBN 1560251875

- Colonialism is Doomed, by Che Guevara, Ministry of External Relations: Republic of Cuba, 1964, ASIN B0010AAN1K

- Critical Notes on Political Economy: A Revolutionary Humanist Approach to Marxist Economics, by Ernesto Guevara, Ocean Press (AU), 2008, ISBN 1876175559

- Episodes of the Cuban Revolutionary War, 1956-58, by Ernesto Guevara, Pathfinder Press (NY), 1996, ISBN 0873488245

- Guerrilla Warfare: Authorized Edition , by Ernesto Guevara, Ocean Press (AU), 2006, ISBN 1920888284

- London Bulletin Number 7, Che's Diaries, by Che Guevara, Bertrand Russell Peace Foundation, 1968, ASIN B000LARAC0

- Manifesto: Three Classic Essays on How to Change the World, by Ernesto Che Guevara, Karl Marx, Friedrich Engels, & Rosa Luxemburg, Ocean Press (NY), 2005, ISBN 1876175982

- Marx & Engels: An Introduction, by Che Guevara, Ocean Press, 2007, ISBN 1920888926

- Our America And Theirs: Kennedy And The Alliance For Progress, by Ernesto Guevara, Ocean Press, 2006, ISBN 1876175818

- Reminiscences of the Cuban Revolutionary War: Authorized Edition, by Ernesto "Che" Guevara, Ocean Press (AU), 2005, ISBN 1920888330

- Self Portrait Che Guevara, by Ernesto Guevara & Victor Casaus, Ocean Press (AU), 2004, ISBN 1876175826

- Socialism and Man in Cuba, by Ernesto Guevara & Fidel Castro, Pathfinder Press (NY), 1989, ISBN 0873485777

- The African Dream: The diaries of the Revolutionary War in the Congo, by Ernesto "Che" Guevara, Grove Press, 2001, ISBN 0802138349

- The Bolivian Diary of Ernesto Che Guevara, by Ernesto "Che" Guevara, Pathfinder Press, 1994 ISBN 0873487664

- The Che Guevara Reader, by Ernesto Guevara, Ocean Press (AU), 2003, ISBN 1876175699

- The Diary of Che Guevara: Bolivia: November 7, 1966-October 7, 1967, by Che Guevara, Bantam Extra, 1968, ASIN B000BD037G

- The Diary of Che Guevara: The Secret Papers of a Revolutionary, by Che Guevara, Amereon Ltd, ISBN 0891902244

- The Great Debate on Political Economy, by Che Guevara, Ocean Press, 2006, ISBN 1876175540

- The Motorcycle Diaries: A Journey Around South America, by Ernesto Che Guevara, Verso, 1996, ISBN 1857023994

- The Role of Foreign Aid in the Deveopment of Cuba, by Che Guevara, Editorial en Marcha, 1962, ASIN B001159NRO

- To Speak the Truth: Why Washington's "Cold War" Against Cuba Doesn't End, by Ernesto Guevara & Fidel Castro, Pathfinder, 1993, ISBN 0873486331

Supplementary resources

Content notes

- ^ Basque: Re origin of the surname Guevara — "Basque: Castilianized form of Basque Gebara, a habitational name from a place in the Basque province of Araba.[dead link]

- ^ Galway: The Lynch family was one of the famous 14 Tribes of Galway. Patrick, who was born in Lydican Castle, Claregalway, travelled extensively around South America before finally settling in Argentina where he became a prosperous merchant. His descendants include the Chilean rear admiral Patricio Lynch Zaldívar (1824-1886), and the distinguished Argentine writers Benito Lynch (1882-1951) and Adolfo Bioy Casares (1914-1999).[77]

- ^ Diploma: While commonly referred to as a doctor, the medical degree conferred was of a medic, a lower degree of the time.[78] Also note, the below sources show record of a medic education, but then identify it as a "doctor", confused with the fact that medical education of the time could lead to two outcomes, that of a medic, or after clinical training that of a doctor.

- The University de Buenos Aires has no record of him receiving a medical degree or a medic degree, though it is likely his educational records were lost or destroyed.

- Employed as a medic because he was unable to get his clinical internship years (i.e. the required clinical years to become a doctor; medical studies could be completed to become either a medic (sans clinical training) or a doctor (with clinical years)[79]

- "In March (1953), he passed his finals and obtained his diploma as a physician. His specialty was dermatology. A few months later he went back on the road, never to return to Argentina until he had become the world-famous Comandante Che Guevara."[80]

- "In June (1953), Ernesto received a copy of his doctor's degree, and a few days later he celebrated his twenty-fifth birthday"[81]

- "12 de junio de 1953.- La Facultad de Ciencias Médicas de la Universidad de Buenos Aires le expide a Ernesto Guevara de la Serna el certificado de haber concluido la carrera de medicina. Esto se refleja en el legajo 1058, registro 1116, folio 153. Después participa en una fiesta de despedida que sus compañeros de la Clínica del doctor Salvador Pisani le hacen en la hacienda de la señora Amalia María Gómez Macías de Duhau."[82]

- "One year later, having completed his medical degree, he left Argentina for good."[83]

- "He received a medical degree from the University of Buenos Aires in 1953."[84]

- "he completed medical studies in 1953" (as a medic)[85]

- ^ Ibero-America: Guevara gave a brief speech at the San Pablo leprosarium in Peru on the occasion of his 24th birthday.[86]

- ^ Children:

- With Hilda Gadea (married 18 August 1955; divorced 22 May 1959):

- Hilda Beatriz Guevara Gadea, born 15 February 1956 in Mexico City; died 21 August 1995 in Havana, Cuba.

- With Aleida March (married 2 June 1959):

- Aleida Guevara March, born 24 November 1960 in Havana, Cuba

- Camilo Guevara March, born 20 May 1962 in Havana, Cuba

- Celia Guevara March, born 14 June 1963 in Havana, Cuba

- Ernesto Guevara March, born 24 February 1965 in Havana, Cuba

- With Lilia Rosa López (extramarital):

- With Hilda Gadea (married 18 August 1955; divorced 22 May 1959):

- ^ INRA: Appointed Director of the Industrialization Department of the National Institute for Agrarian Reform on October 7 1959.

- ^ BNC: Appointed President of the National Bank of Cuba on November 26 1959.

- ^ Signature: "If my way of signing is not typical of bank presidents ... this does not signify, by any means, that I am minimizing the importance of the document — but that the revolutionary process is not yet over and, besides, that we must change our scale of values." — Ernesto Guevara[88][89]

- ^ MININD: appointed Minister of Industries on February 23 1961.

- ^ Ley de la Sierra: The Penal Law of the War of Independence (July 28, 1896) was reinforced by Rule 1 of the Penal Regulations of the Rebel Army, approved in the Sierra Maestra February 21, 1958, and published in the army's official bulletin (Ley penal de Cuba en armas, 1959).

- ^ Algeria: In September 1962, Algeria asked Cuba for assistance when Morocco declared war on it over their dispute concerning the territory formerly known as the Spanish Sahara.[90][91]

- ^ Kabila: In May 1997, Laurent-Désiré Kabila overthrew the government of Mobutu Sese Seko and became President of the Democratic Republic of the Congo.

- ^ NSA: "The intercept operators knew that Dar-es-Salaam was serving as a communications center for the fighters, receiving messages from Castro in Cuba and relaying them on to the guerrillas deep in the bush.[92]

- ^ Camp: The purchase of the acreage in the Ñancahuazú region was in direct contravention of Guevara's directive that the land for the camp should be purchased in the Alto Beni region.

- ^ USMilitary: "U.S. military personnel in Bolivia never exceeded 53 advisors, including a sixteen-man Mobile Training Team (MTT) from the 8th Special Forces Group based at Fort Gulick, Panama Canal Zone."[93]

- ^ Message: For example, on August 31 1967 Che wrote in his diary "Hay mensaje de Manila pero no se pudo copiar.", i.e. "There is a (coded radio) message from Manila ('Manila' being the code name for Havana) but we couldn't copy it." The content of this message has not been revealed, but it may have been of critical importance since by then Castro and the other Cubans who were directing the guerrillas' support network from Havana had to be aware of their dire straits.

- ^ Barrientos: Although Barrientos never revealed his motives for ordering the summary execution of Guevara.

- ^ Amputation: Castañeda, Jorge G., Che Guevara: Compañero, New York: 1998, Random House, pp. xiii - xiv; pp. 401–402. Guevara's amputated hands, preserved in formaldehyde, turned up in the possession of Fidel Castro a few months later.

- ^ Mausoleum: On December 30 1998 the remains of ten more guerrillas who had fought alongside Guevara in Bolivia and whose secret burial sites there had been recently discovered by Cuban forensic investigators were placed inside the "Che Guevara Mausoleum" in Santa Clara.

Source notes

Parameter error in {{ISBN}}: Missing ISBN.

- ^ Time 100: Che Guevara By Ariel Dorfman, June 14 1999.

- ^ Maryland Institute of Art, referenced at BBC News, "Che Guevara photographer dies", 26 May 2001.Online at BBC News, accessed January 42006.

- ^ Anderson, Jon Lee (1997), Che Guevara: A Revolutionary Life, New York: Grove Press, pp. 66Ndash, 67, ISBN 0-8021-1600-0.

- ^ Guevara Lynch, Ernesto. Aquí va un soldado de América. Barcelona: Plaza y Janés Editores, S.A., 2000, p. 26.

- ^ Radio Cadena Agramonte, "Ataque al cuartel del Bayamo" Online, accessed February 25 2006

- ^ a b "Foreign Relations, Guatemala, 1952-1954". www.state.gov. Retrieved 2008-02-29..

- ^ Anderson, Jon Lee. Che Guevara: A Revolutionary Life, New York: 1997, Grove Press, p. 144

- ^ Taibo, Paco Ignacio II. Ernesto Guevara, también conocido como el Che, p. 74.

- ^ a b Anderson, Jon Lee (1997), Che Guevara: A Revolutionary Life, New York: Grove Press, p. 194, ISBN 0-8021-1600-0. Cite error: The named reference "anderson2" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ DePalma, Anthony (2006), The Man Who Invented Fidel: Castro, Cuba, and Herbert L. Matthews of the New York Times, New York: Public Affairs, pp. 110–111, ISBN 1-58648-332-3.

- ^ Anderson, Jon Lee (1997), Che Guevara: A Revolutionary Life, New York: Grove Press, pp. 269–270, ISBN 0-8021-1600-0

- ^ Castañeda, Jorge G., Che Guevara: Compañero, New York: 1998, Random House, pp 105, 119.

- ^ Anderson pp. 269–270, 277–278.

- ^ Castro, Fidel (editors Bonachea, Rolando E. and Nelson P. Valdés). Revolutionary Struggle. 1947–1958. Cambridge, Massachusetts and London: MIT Press, 1972, pp. 439–442.

- ^ Castro, Fidel. (Speech given in Palma Soriano, Cuba. Online

- ^ Dorschner, John and Roberto Fabricio. The Winds of December: The Cuban Revolution of 1958, New York: 1980, Coward, McCann & Geoghegen, ISBN 0698109937, pages 41–47, 81–87.

- ^ "Castro: The Great Survivor". BBC News. 2000. Retrieved 2006-05-15.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Thirty Years of Cuban Revolutionary Penal Law, by Raul Gomez Treto, Latin American Perspectives, Vol. 18, No. 2, Cuban Views on the Revolution (Spring, 1991), pp. 114-125 (pg 115-116)

- ^ Anderson, Jon Lee. Che Guevara: A Revolutionary Life, New York: 1997, Grove Press, p. 372 and p. 425

- ^ Anderson, Jon Lee. Che Guevara: A Revolutionary Life, ISBN 0-8021-1600-0, New York: 1997, Grove Press, p. 376.

- ^ Thirty Years of Cuban Revolutionary Penal Law, by Raul Gomez Treto, Latin American Perspectives, Vol. 18, No. 2, Cuban Views on the Revolution (Spring, 1991), pp. 114-125 (pg 116)

- ^ Different sources cite different numbers of executions. Anderson states that "several hundred people were officially tried and executed across Cuba." p.387. Dr. Armando M. Lago of the Cuba Archive, gives the figure as 216 documented executions in two years. Others give far higher figures.

- ^ Anderson, Jon Lee. Che Guevara: A Revolutionary Life, ISBN 0-8021-1600-0, New York: 1997, Grove Press, p. 423.

- ^ Anderson, Jon Lee. Che Guevara: A Revolutionary Life, ISBN 0-8021-1600-0, New York: 1997, Grove Press, p. 434–437.

- ^ Anderson, Jon Lee. Che Guevara: A Revolutionary Life, ISBN 0-8021-1600-0, New York: 1997, Grove Press, p. 438–439.

- ^ Cuban Information Archives, "La Coubre explodes in Havana 1960." Online, accessed February 26 2006; pictures can be seen at Cuban site fotospl.com.

- ^ PBS: Che Guevara, Popular but Ineffective

- ^ Anderson, Jon Lee. Che Guevara: A Revolutionary Life, New York: 1997, Grove Press, p. 628

- ^ Che Guevara speaking French: L'interview de Che Guevara, 1964, (9:43), Français, Video Clip

- ^ Ernesto Che Guevara, (editors Rolando E. Bonachea and Nelson P. Valdés), Che: Selected Works of Ernesto Guevara, Cambridge, MA: 1969, p. 350.

- ^ Ernesto Che Guevara, "English Translation of Complete Text of Algiers Speech", Online at Sozialistische Klassiker, accessed January 42006.

- ^ Ernesto Che Guevara, (editors Rolando E. Bonachea and Nelson P. Valdés), Che: Selected Works of Ernesto Guevara, Cambridge, MA: 1969, pp. 352-59.

- ^ Ernesto Che Guevara, "English Translation of Complete Text of Algiers Speech", Online at Sozialistische Klassiker, accessed January 42006.

- ^ Ernesto Che Guevara, "English Translation of Complete Text of his Message to the Tricontinental", or see Original Spanish text at Wikisource .

- ^ Ernesto Che Guevara, "Che Guevara's Farewell Letter", 1965. English translation of complete text: Che Guevara's Farewell Letter at Wikisource.

- ^ Ben Bella, Ahmed. "Che as I knew him, by Ahmed Ben Bella". mondediplo.com. Retrieved 2008-02-28.

- ^ Heikal's account of Guevara's conversations with Nasser in February and March of 1965 lends further credence to this interpretation. See Heikal, Mohamed Hassanein. The Cairo Documents, pp 347–357.

- ^ Gálvez, William. Che in Africa: Che Guevara's Congo Diary, Melbourne, 1999: Ocean Press, p 62.

- ^ Gott, Richard. Cuba: A new history, Yale University Press 2004, p219.

- ^ BBC News, "Profile: Laurent Kabila", 26 May 2001. Online at BBC News, accessed January 5 2006.

- ^ Ireland's Own, "From Cuba to Congo, Dream to Disaster for Che Guevara". Online at irelandsown.net, accessed January 11 2006.

- ^ Ernesto Che Guevara, translated from the Spanish by Patrick Camiller, The African Dream, New York: Grove Publishers, 2000, p.1.

- ^ Castañeda, Jorge G., Che Guevara: Compañero, New York: 1998, Random House, p 316.

- ^ Ernesto Che Guevara, Apuntes Filosóficos, draft.

- ^ Ernesto Che Guevara, Notas Económicas, draft.

- ^ Mittleman, James H. Underdevelopment and the Transition to Socialism - Mozambique and Tanzania, New York: 1981, Academic Press, p. 38.

- ^ Major Donald R. Selvage - USMC, "Che Guevara in Bolivia", 1 April 1985. Online at GlobalSecurity.org, accessed January 5 2006.

- ^ Anderson, Jon Lee (1997), Che Guevara: A Revolutionary Life, New York: Grove Press, p. 693, ISBN 0-8021-1600-0

- ^ U.S. Army, "Memorandum of Understanding Concerning the Activation, Organization and Training of the 2d Ranger Battalion – Bolivian Army (28 April 1967)". Accessed June 19 2006.

- ^ Ryan, Henry Butterfield. The Fall of Che Guevara: A Story of Soldiers, Spies, and Diplomats, New York, 1998: Oxford University Press, p 82–102, inter alia.

- ^ Ernesto Che Guevara, "Excerpt from Pasajes de la guerra revolucionaria:Congo",Online at Cold War International History Project, accessed April 26 2006.

- ^ Castañeda, Jorge G. Che Guevara: Compañero, New York: 1998, Random House, pp 107–112; 131–132.

- ^ Rodriguez, Felix I. and John Weisman. Shadow Warrior/the CIA Hero of a Hundred Unknown Battles (Hardcover), New York: 1989, Publisher: Simon & Schuster.

- ^ NewsMax, "Félix Rodríguez:Kerry No Foe of Castro". Online, accessed February 27 2006.

- ^ Anderson, Jon Lee. Che Guevara: A Revolutionary Life, New York: 1997, Grove Press, p.733.

- ^ Grant, Will. "CIA man recounts Che Guevara's death". news.bbc.co.uk. Retrieved 2008-02-29..

- ^ "Che: A Myth Embalmed in a Matrix of Ignorance", Time Magazine, October 12 1970

- ^ Anderson, Jon Lee. Che Guevara: A Revolutionary Life. New York: Grove Press, 1997, page 739.

- ^ Bolivia marks capture, execution of 'Che' Guevara 40 years ago, SF Chronicle, October 9 2007

- ^ Richard Gott, "Bolivia on the Day of the Death of Che Guevara".Online at Mindfully.org, accessed February 26 2006.

- ^ Lone Bidder Buys Strands of Che’s Hair at U.S. Auction, by Marc Lacey, October 26 2007, NY Times

- ^ National Security Archive. Electronic Briefing Book No. 5 Online, accessed March 25 2007.

- ^ Ernesto Che Guevara, "Diario (Bolivia)". Online, accessed February 26 2006.

- ^ Major Donald R. Selvage - USMC, "Che Guevara in Bolivia", 1 April 1985. Online at GlobalSecurity.org, accessed January 5 2006;

- ^ Alarcón Ramírez, Dariel dit "Benigno". Le Che en Bolivie, Paris: 1997, Éditions du Rocher

- ^ Michael Moynihan, "Neutering Sartre at Dagens Nyheter". Online at Stockholm Spectator. Accessed February 26 2006.

- ^ 'Che Guevara remains a hero to Cubans', People's Weekly World, October 2, 2004

- ^ Hugh Thomas. Cuba: The pursuit of freedom p. 1007.

- ^ Johann Hari: Should Che be an icon? No October 6 2007, The Independent

- ^ The Killing Machine: Che Guevara, from Communist Firebrand to Capitalist Brand. The Independent Institute. online. Accessed November 10, 2006.

- ^ Paquito D'Rivera, "Open letter to Carlos Santana by Paquito D'Rivera in Latin Beat Magazine", 25 March 2005. Find Articles Online, accessed June 18, 2006.

- ^ "Andy Garcia Tells His Cuba Story, at Last". NewsMax.com. Friday, May 5, 2006. Online. Accessed October 24 2006.

- ^ BBC News, "Che Guevara photographer dies", 26 May 2001. Online at BBC News, accessed January 4 2006.

- ^ Photograph of Sandinista election victory parade Online

- ^ Cuba pays tribute to Che Guevara, October 9 2007, BBC

- ^ The Guardian. "Just a pretty face?" Online, accessed October 25 2006.

- ^ For more information, see Dictionary of Irish Latin American Biography Guevara, Ernesto [Che (1928-1967)]

- ^ Ernesto Che Guevara: Mito Y Realidad, by Enrique Ros (ISBN 0897299884)

- ^ Anderson, Jon Lee. Che Guevara: A Revolutionary Life, New York: 1997, Grove Press, p. 139–141

- ^ James, Daniel. Che Guevara: A Biography, New York: Stein and Day, 1969, p. 71.

- ^ Jon Lee Anderson. Che Guevara: A revolutionary life, p-98.

- ^ Che en el tiempo

- ^ PBS http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/amex/castro/peopleevents/p_guevara.html

- ^ MSN Encarta http://encarta.msn.com/encyclopedia_761558812/Che_Guevara.html

- ^ : Encyclopedia Britannica. http://concise.britannica.com/ebc/article-9366272/Che-Guevara

- ^ Guevara, Ernesto Che, Motorcycle Diaries, London: Verso Books, 1995, p.135.

- ^ Castañeda, Jorge G. Che Guevara: Compañero, New York: 1998, Random House, pp 264–265.

- ^ Aleksandr Alexeiev in Cuba después del triunfo de la revolución ("Cuba after the triumph of the revolution")

- ^ Revista de América Latina (Moscow), no. 10, October 1984, p. 57 (referenced in Castañeda, op. cit, p. 169).

- ^ Piero Gliejeses, "Cuba's First Venture in Africa: Algeria, 1961–1965", Journal of Latin American Studies, no. 28, London: Cambridge University Press, Spring 1996, p. 188

- ^ Castañeda, pp. 244–245.

- ^ Bamford, James, Body of Secrets: Anatomy of the Ultra-Secret National Security Agency, New York: Anchor Books, 2002 (Reprint edition), p. 181.

- ^ Che Guevara in Bolivia by Major Donald R. Selvage.

References

- Alarcón Ramírez, Dariel ("Benigno"). Memorias de un Soldado Cubano: Vida y Muerte de la Revolución. Barcelona: Tusquets Editores S.A., 2002. ISBN 84-8310-014-2

- Alarcón Ramírez, Dariel dit "Benigno". Le Che en Bolivie. Éditions du Rocher, 1997. ISBN 2-268-02437-7

- Anderson, Jon Lee. Che Guevara: A Revolutionary Life. New York: Grove Press, 1997. ISBN 0-8021-1600-0

- Bamford, James. Body of Secrets: Anatomy of the Ultra-Secret National Security Agency. New York: Anchor Books, 2002 (Reprint edition). ISBN 0-385-49908-6

- Bravo, Marcos. La Otra Cara Del Che. Bogota, Colombia: Editorial Solar, 2005. “I’d like to confess, papá, at that moment I discovered that I really like killing.” Guevara writing to his father.

- Castañeda, Jorge G. Che Guevara: Compañero. New York: Random House, 1998. ISBN 0-679-75940-9

- Castro, Fidel (editors Bonachea, Rolando E. and Nelson P. Valdés). Revolutionary Struggle. 1947–1958. Cambridge, Massachusetts and London: MIT Press, 1972. ISBN 0-262-02065-3

- Feldman, Allen 2003. Political Terror and the Technologies of Memory: Excuse, Sacrifice, Commodification, and Actuarial Moralities. Radical History Review 85, 58–73.

- Escobar, Froilán and Félix Guerra. Che: Sierra adentro (Che: Deep in the Sierra). Havana: Editora Política, 1988.

- Fuentes, Norberto. La Autobiografía De Fidel Castro ("The Autobiography of Fidel Castro"). Mexico D.F: Editorial Planeta, 2004. ISBN 84-233-3604-2, ISBN 970-749-001-2

- Gálvez, William. Che in Africa: Che Guevara's Congo Diary. Melbourne: Ocean Press, 1999. ISBN 1-876175-08-7

- George, Edward. The Cuban Intervention In Angola, 1965–1991: From Che Guevara To Cuito Cuanavale. London & Portland, Oregon: Frank Cass Publishers, 2005. ISBN 0-415-35015-8

- Gliejeses, Piero. Cuba's First Venture in Africa: Algeria, 1961–1965, Journal of Latin American Studies, no. 28, London: Cambridge University Press, Spring 1996.

- Granado, Alberto. Travelling with Che Guevara - The Making of a Revolutionary. New York: Newmarket Press, 2004, ISBN 1-55704-640-9 (hardcover), ISBN 1-55704-639-5 (pbk.)

- Guevara, Ernesto "Che". Pasajes de la guerra revolucionaria

- Guevara, Ernesto "Che" (editors Bonachea, Rolando E. and Nelson P. Valdés). Che: Selected Works of Ernesto Guevara, Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1969. ISBN 0-262-52016-8

- Guevara, Ernesto "Che" (editor Waters, Mary Alice). Episodes of the Cuban Revolutionary War 1956–1958. New York: Pathfinder, 1996. ISBN 0-87348-824-5 (See reference to "El Viscaíno" on page 186).

- Guevara, Ernesto "Che", translated from the Spanish by Patrick Camiller. The African Dream, New York: Grove Publishers, 2000. ISBN 0-8021-3834-9

- Guevara, Ernesto "Che". The Great Debate on Political Economy, New York: 2006, Ocean Press, ISBN-10: 1876175540, ISBN-13: 978-1876175542

- Guevara Lynch, Ernesto. Aquí va un soldado de América. Barcelona: Plaza y Janés Editores, S.A., 2000. ISBN 84-01-01327-5

- Heikal, Mohamed Hassanein. The Cairo Documents. New York: Doubleday & Company, Inc., 1973. ISBN 0-385-06447-0

- Holland, Max. Private Sources of U.S. Foreign Policy William Pawley and the 1954 Coup d'État in Guatemala in Journal of Cold War Studies, Volume 7, Number 4, Fall 2005, pp. 36–73.

- James, Daniel. Che Guevara: A Biography. New York: Stein and Day, 1969. ISBN 0812813480

- James, Daniel. Che Guevara. New York: Cooper Square Press, 2001. ISBN 0-8154-1144-8

- Kahn, David. The Codebreakers: The Story of Secret Writing. New York: Macmillan, 1967. ISBN 0684831309

- Matos, Huber. Como llegó la Noche ("As night arrived"). Barcelona: Tusquet Editores, SA, 2002. ISBN 84-8310-944-1

- Miná, Gianni. An Encounter with Fidel. Melbourne: Ocean Press, 1991. ISBN 1-875284-22-2

- Morán Arce, Lucas. La revolución cubana, 1953–1959: Una versión rebelde ("The Cuban Revolution, 1953–1959: a rebel version"). Ponce, Puerto Rico: Imprenta Universitaria, Universidad Católica, 1980. ISBN B0000EDAW9.

- Peña, Emilio Herasme. La Expedición Armada de junio de 1959, Listín Diario, (Dominican Republic), 14 June 2004.

- Peredo-Leigue, Guido "Inti". Mi campaña junto al Che, México: Ed. Siglo XXI, 1979. Template:PDFlink.

- Rodriguez, Félix I. and John Weisman. Shadow Warrior/the CIA Hero of a Hundred Unknown Battles. New York: Simon & Schuster, 1989. ISBN 0-671-66721-1

- Rojo del Río, Manuel. La Historia Cambió En La Sierra ("History changed in the Sierra"). 2a Ed. Aumentada (Augmented second edition). San José, Costa Rica: Editorial Texto, 1981.

- Ros, Enrique 2003. Fidel Castro y El Gatillo Alegre: Sus Años Universitarios (Colección Cuba y Sus Jueces). Miami: Ediciones Universal. ISBN 1-59388-006-5

- Ryan, Henry Butterfield. The Fall of Che Guevara: A Story of Soldiers, Spies, and Diplomats. New York: Oxford University Press, 1998. ISBN 0-19-511879-0

- Taibo, Paco Ignacio II. Ernesto Guevara, también conocido como el Che. Barcelona: Editorial Planeta, 1999. ISBN 84-08-02280-6

- Thomas, Hugh. Cuba or the Pursuit of Freedom. Cambridge, MA: Da Capo Press, April 1998 (Updated edition). ISBN 0-306-80827-7

- Villegas, Harry "Pombo". Pombo : un hombre de la guerrilla del Che: diario y testimonio inéditos, 1966–1968. Buenos Aires: Ediciones Colihue S.R.L., 1996. ISBN 950-581-667-7

External links

Photos/interactive media

- ABC News: Life and Death of Che Guevara

- BBC Audio: CIA Agent Felix Rodriguez Recounts Che's Death, October 8, 2007

- BBC Video: Fidel Castro Visits Boyhood Home of Che Guevara, July 23, 2006

- BBC Video: Che Remembered 40 Years On, October 8, 2007

- BBC: Your Che Guevara Images Set 1 --- Set 2

- MSNBC Slideshow: In Cuba, Che Still Sells Revolution

- NY Daily News: Photos of Che and his Wife (Alieda March)

- NY Times Interactive Gallery: A Revolutionary Afterlife

- Reuters Slideshow: "Honoring Che"

- Rodovid: Che Guevara's Genealogy and Family Tree

- Smithsonian Global Sound: Che Guevara Speaks

Archival footage

- Che Reciting a Poem, (0:58), English subtitles, from El Che: Investigating a Legend - Kultur Video 2001, Video Clip

- Che Showing Support for Fidel Castro, (0:21), English subtitles, from El Che: Investigating a Legend - Kultur Video 2001, Video Clip

- Che Speaking about Labor, (0:27), English subtitles, from El Che: Investigating a Legend - Kultur Video 2001, Video Clip

- Che Speaking about the Bay of Pigs Invasion, (0:17), English subtitles, from El Che: Investigating a Legend - Kultur Video 2001, Video Clip

- Che Speaking on the U.S. Presidency, (0:32), English subtitles, from El Che: Investigating a Legend - Kultur Video 2001, Video Clip

- Che Speaking out Against Imperialism, (1:19), English subtitles, from El Che: Investigating a Legend - Kultur Video 2001, Video Clip

Template:Link FA Template:Link FA Template:Link FA Template:Link FA Template:Link FA Template:Link FA Template:Link FA

- Wikipedia neutral point of view disputes from February 2008

- Articles needing cleanup from February 2008

- Cleanup tagged articles without a reason field from February 2008

- Wikipedia pages needing cleanup from February 2008

- Articles with dead external links from February 2008

- Che Guevara

- Marxist theorists

- Guerrilla warfare theorists

- Marxism

- Communism

- Socialism

- Argentine revolutionaries

- Executed revolutionaries

- Argentine communists

- Cuban communists

- People from Rosario

- Basque Argentines

- Irish Argentineans

- 1928 births

- 1967 deaths