Samuel de Champlain

Samuel de Champlain | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | about 1567 unknown |

| Died | December 25,1635 |

| Occupation(s) | Sailor, Navigator, and Cartographer |

| Known for | Exploration of New France, founder of Quebec City, Canada, father of New France |

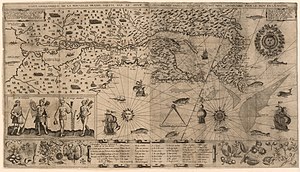

Samuel de Champlain, (c. 1567 [1] - 1635) the "father of New France," was born into a Protestant family in the Province of Saintonge, lived when young in the town of Brouage, a seaport on France's west coast and made a journey through Canada before, he died in 1635 in Québec. A sailor, he also came to be respected as a talented navigator, a cartographer, and the founder of Quebec City. He was also integral in opening North America to French trade, especially the fur trade. Champlain's pattern was to spend several months or years exploring North America and then head back to France to raise more funds for further explorations.

Early travels

He lived [2] in Brouage, France before the end of the 16th century, as was reported in the title of his 1603 book. He belonged to either a Protestant family, or a tolerant one, in a Protestant region, as his Biblical first name (Samuel) was not usually given to Catholic children.[3]

Champlain arrived on board the Bonne-Renommée on his first trip to North America on March 15, 1603, as an observer, with members of a fur-trading expedition. Although he had no official assignment on the voyage commanded by François Gravé Du Pont, he created a map of the St. Lawrence River and after his return to France on September 20th, wrote an account published as Des Sauvages: ou voyage de Samuel Champlain, de Brouages, faite en la France nouvelle l'an 1603 ("Concerning the Savages: or travels of Samuel Champlain, of Brouages, made in New France the year 1603").[4] Asked by Henry IV to make a report on his further discoveries, Champlain joined another expedition to New France in the spring of 1604 led by Pierre Dugua, Sieur de Monts, a Protestant merchant given fur trade monopoly in new France by Henry IV. Champlain helped found the Saint Croix Island settlement in the Bay of Fundy. However, after enduring a harsh winter on the island, the settlement was abandoned the following spring when Champlain relocated the settlers to the Fundy coast of Nova Scotia at Port Royal. Champlain remained at the site until 1607, while he explored the Atlantic coast.

In 1605 and 1606, Champlain explored the land that is now Chatham, Cape Cod as a prospective settlement but small skirmishes with the resident Monomoyick Indians dissuaded him from the idea. He named the area Port Fortune.[5]

Founding of Quebec City

In the spring of 1607, three ships left the French port of Honfleur, one of them the Don-de-Dieu commanded by Champlain. In June, the small group of settlers arrived at Tadoussac. There, they left the ships and continued to Québec in small boats. On July 3, 1608, Champlain landed at the "point of Quebec" and set about fortifying the area by building three main buildings (each two stories tall), to which he referred collectively as "l'Abitation", and also a moat 12 feet (4 m) wide. This was to become the city of Quebec. Fortifying Quebec City became one of his passions, which he embarked on periodically for the rest of his life.

Relations and war with natives

During the summer of 1609, Champlain attempted to form better relations with the local First Nations. He made alliances with the Wendat that the French called Huron and with the Algonquin, the Montagnais and the Etchemin, who lived in the area of the St. Lawrence River and who demanded that Champlain helped them in their war against the Iroquois, who were much more to the south. Champlain set off with 9 French soldiers and 300 natives in order to explore the Rivière des Iroquois (now Richelieu River) when he subsequently mapped Lake Champlain. Having had no encounters with the Iroquois at this point many of the men headed back, leaving Champlain with only 2 Frenchmen and 60 natives.

On July 29 at Ticonderoga (now Crown Point, New York), Champlain and his party encountered a group of Iroquois. A battle began the next day. 200 Iroquois advanced on Champlain's position as a native guide pointed out the 3 Iroquois chiefs. Champlain fired his arquebus and killed 2 of them with one shot. One of his men killed the third. The Iroquois turned and fled. This was to set the tone for French-Iroquois relations for the next one hundred years.

After this expedition, he returned to France in an unsuccessful attempt, with the Sieur de Monts, to renew their fur trade monopoly. They did, however, form a society with some Rouen merchants, in which Quebec would become an exclusive warehouse for their fur trade and, in return, the Rouen merchants would support the settlement.

Exploration of New France

On March 29, 1613, he arrived back in New France and proclaimed his new royal commission. Champlain set out on May 27 to continue his exploration of the Huron country and in hopes of finding the "northern sea" he had heard about (probably Hudson Bay). He traveled the Ottawa River, later giving the first description of this area (In 1953, a rock was found at a location now known as the Champlain lookout, which bore the inscription Champlain juin 2, 1613). It was in June that he met with Tessouat, the Algonquin chief of Allumettes Island, and offered to build the tribe a fort if they were to move from the area they occupied, with its poor soil, to the locality of the Lachine Rapids.

By August 26 Champlain was back in Saint-Malo. There he wrote an account of his life from 1604 to 1612 and his journey up the Ottawa river, his Voyages[6] and published another map of New France. In 1614 he formed the "Compagnie des Marchands de Rouen et de Saint-Malo" and "Compagnie de Champlain", which bound the Rouen and Saint-Malo merchants for eleven years. He returned to New France in the spring of 1615 with four Recollects in order to further religious life in the new colony. The Roman Catholic Church would be given en seigneurie large and valuable tracts of land estimated at nearly 30% of all the lands granted by the French Crown in New France. [7]

Champlain continued to work to improve relations with the natives promising to help them in their struggles against the Iroquois. With his native guides he explored further up the Ottawa River and reached Lake Nipissing. He then followed the French River until he reached the fresh-water sea he called Lac Attigouautau (now Lake Huron).

In 1615, Champlain was escorted through the Peterborough area by a group of Hurons. He used the ancient portage between Chemong Lake and Little Lake (now Chemong Road); stayed for a short period of time in Bridgenorth area.

Military expedition

On September 1, at Cahiagué (on Lake Simcoe), he started a military expedition. The party passed Lake Ontario at its eastern tip where they hid their canoes and continued their journey by land. They followed the Oneida River until they found themselves at an Onondaga fort. Pressured by the Hurons to attack prematurely, the assault failed. Champlain was wounded twice in the leg by arrows, one in his knee. The attack lasted three hours until they were forced to flee.

Although he did not want to, the Hurons insisted that Champlain spend the winter with them. During his stay he set off with them in their great deer hunt, during which he became lost and was forced to wander for three days living off game and sleeping under trees until he met up with a band of Indians by chance. He spent the rest of the winter learning "their country, their manners, customs, modes of life". On May 22, 1616, he left the Huron country and was back in Quebec on July 11 before heading back to France on July 2.

Improving administration in New France

Champlain returned to New France in 1620 and was to spend the rest of his life focusing on administration of the country rather than exploration.

Champlain spent the winter building Fort Saint-Louis on top of Cap Diamant. By mid-May he learned that the fur trade had been handed over to another company led by the Caen brothers. After some tense negotiations, it was decided to merge the two companies under the direction of the Caens. Champlain continued to work on relations with the Indians and managed to impose on them a chief of his choice. He also managed to create a peace treaty with the Iroquois tribes.

Champlain continued to work on improving his fortification around what became Quebec City, laying the first stone on May 6, 1624. On August 15 he once again returned to France where he was encouraged to continue his work as well as to continue to look for a passage to China. At the time, most of the European powers believed that North America included a passage on land to China. By July 5th he was back at Quebec and continued expanding the city.

Things were not to continue well for Champlain and his small village. Supplies were low during the summer of 1628 and English merchants had pillaged Cap Tourmente in early July. On July 10, Champlain received a summons from the Kirke brothers, English merchants. Champlain refused to deal with them and, in response, the English cut off supplies from going to the city. By the spring of 1629 supplies were dangerously low and Champlain was forced to send people to Gaspé to conserve rations. On July 19, the Kirke brothers arrived and Champlain was forced to negotiate the terms of the cities' capitulation. By October 29, Champlain found himself in London.

A member of the Compagnie des Cent-Associés, from 1629 to 1635 Champlain was commander in New France "in the absence of my Lord the Cardinal de Richelieu". [2] During the next several years Champlain wrote Voyages de la Nouvelle France dedicated to Cardinal Richelieu as well as Traitté de la marine et du devoir d’un bon marinier. It wasn't until the Treaty of Saint-Germain-en-Laye in 1632 that Quebec was given back to France and on March 1, 1633, Champlain reclaimed his role as commander of New France on behalf of Richelieu.

Champlain returned to Quebec on May 22, 1633, after an absence of four years. On August 18, 1634, he sent a report to Richelieu stating that he had rebuilt on the ruins of Quebec, enlarged its fortifications, constructed another habitation 15 leagues upstream, as well as another one at Trois-Rivières. He had also begun an offensive against the Iroquois Indians stating he wanted them wiped out or "brought to reason".

Illness and death

By October 1635, Champlain was stricken with a stroke. He died on December 25,1635 leaving no immediate heirs. He was buried temporarily in the church while construction was finished on the chapel of Monsieur le Gouverneur. Unfortunately, it was destroyed by fire in 1640 and immediately rebuilt but nothing is known of it after 1640, although after 1674 it no longer existed. As such the exact burial site of Champlain is unknown.

However, Jesuit records tell us he died in the hands of his friend Charles Lallemant who also heard his last confession, a reassuring point for a Catholic of the period.

Honours

Many sites and landmarks were named to honour Champlain, who remains, to this day, a prominent historical figure in many parts of Acadia, Ontario, Quebec, New York, and Vermont. They include:

- Lake Champlain, Champlain Valley, The Champlain Trail Lakes, and Champlain Sea, a glacial sea which disappeared 6000 years before Champlain was born;

- Two communities in New York named Champlain, as well as a township in Ontario and a municipality in Québec;

- Fort Champlain at the Royal Military College of Canada in Kingston, Ontario was named in his honour in 1965. This dormitory houses 8, 9 and 10 Squadrons;

- The provincial electoral district of Champlain, Quebec;

- Champlain Bridge, which connects the island of Montreal to the mainland;

- A French school, located in Saint John, New Brunswick; Champlain College, in Burlington, Vermont, as well as a CEGEP in Quebec;

- Streets named Champlain in numerous cities, including Québec and Shawinigan;

- Marriott Château Champlain hotel, in Montréal.

- Samuel de Champlain Provincial Park, a provincial park in northern Ontario near the town of Mattawa.

Anecdote

There is no authentic portrait of Champlain. The only surviving picture we have of him is a drawing illustrating the battle at Lake Champlain in 1609, in which the facial features are too vague to make out. Some much-reproduced fictional "portraits of Champlain" have been shown to be actually made after a portrait of Michel Particelli d'Émery, by Balthasar Moncornet. /* Anecdote */

Notes

- ^ There is evidence that Champlain might have been born as late as about 1580. This is first mainly based on the known year of birth (1560) of François Gravé, and on what Champlain wrote about Gravé, when reporting the1619 events: (translation) "His age would make me respect him like my father." (In: Champlain, "Les Voyages [...] depuis l'an 1603 jusques en l'an 1629", published in 1632.)

In 1978, Jean Liebel wrote On a vieilli Champlain (They made Champlain older), in the Revue d'histoire de l'Amérique française (RHAF, number XXXII, pages 229 to 237), after a full examination of all the old and new sources, concluding that "1580" is a much better approximated year than the proofless "1567" coming from Pierre-Damien Rainguet's 1851 Biographie Saintongeaise (ou Dictionnaire historique de tous les personnages qui se sont illustrés […] : see pp. 140-141, or pp. 148-149 of these digital photocopies). Nowadays, most of the historians agree with Liebel on the "1580". See in recent works, like Champlain: the birth of French America / edited by Raymonde LItalien and Denis Vaugeois. (McGill-Queen's University Press, 2004). - ^ Champlain never wrote where he was born, but were he lived when young: in Brouage.

- ^ According to Alain Laberge, Chair of the History Department at Quebec City's Laval University, also a specialist in the history of New France, Champlain was a Protestant. A guest on the February 6, 2008 CBC radio program, Sounds Like Canada, Professor Laberge said that the fact of Champlain's Protestantism was downplayed and omitted from education material by the Roman Catholic Church who controlled the Province of Quebec's education system until 1963.

- ^ Since his marriage contract, at the end of 1609 in Paris, and by 1612, when this was reprinted, he was credited as "sieur de Champlain [1].

- ^ NPS Archeology Program: Visit Archeology

- ^ Les voyages du Sieur de Champlain, Saintangeois, capitaine ordinaire pour le Roy en la Marine.

- ^ Dalton, Roy. The Jesuit Estates Question 1760-88, p. 60. University of Toronto Press, 1968.

- ^ François Pierre Guillaume Guizot, A Popular History of France from the Earliest Times Vol. 6, Chapter 53, (Boston: Dana Estes & Charles E. Lauriat (Imp.), 19th C.), 190.

- ^ Morris Bishop, Samuel de Champlain: The Life of Fortitude (New York: Knopf, 1948), 6-7.

10. Nobody knew what Samuel really looked like. But people needed a picture of him when he got famous. All people knew was that he had a goatee. Someone went into the newspaper and cut out a picture of someone with a goatee. Turns out that that picture was the picture of the man who was a murder that was going to get hung the next day.

References

- Samuel Eliot Morison, Samuel de Champlain: Father of New France (Little Brown, 1972) ISBN 0-316-58399-5

- Champlain : the birth of French America / edited by Raymonde LItalien and Denis Vaugeois. (McGill-Queen's University Press, 2004) ISBN 0-7735-2850-4

- Biography at the Dictionary of Canadian Biography Online

External links

- The Canadian Museum of Civilization - Face-to-Face - The Canadian Personalities Hall

- The Samuel de Champlain Portal

- Full text http://www.gutenberg.net/etext/6825 Vol. 3

- Samuel de Champlain Biography by Appleton and Klos

- Works by Samuel de Champlain at Project Gutenberg

- Biography at the Dictionary of Canadian Biography Online

- Description of Champlain's voyage to Chatham, Cape Cod in 1605 and 1606.'

- Champlain's tomb: State of the Art Report. (in French, translation with Alta-Vista available

- Biography at the Museum of Civilization

- Champlain in Acadia (A Historica project from 7th Floor Media)

- Champlain, Samuel de (From The Canadian Encyclopedia)

- Biography at the Museum of Civilization

- Les Voyages de la Nouvelle France... 1632, from Rare Book Room

- Champlain College (Vermont) site celebrates 400th anniversary of Samuel de Champlain’s arrival on Lake Champlain