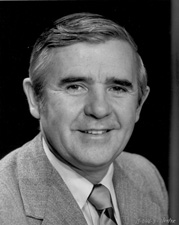

Charles Mathias

Charles "Mac" Mathias, Jr. | |

|---|---|

| |

| United States Senator from Maryland | |

| In office January 3, 1969 – January 6, 1987 | |

| Preceded by | Daniel Brewster |

| Succeeded by | Barbara Mikulski |

| Member of the U.S. House of Representatives from Maryland's 6th district | |

| In office January 3, 1961 – January 3, 1969 | |

| Preceded by | John R. Foley |

| Succeeded by | John Glenn Beall, Jr. |

| Personal details | |

| Political party | Republican |

Charles McCurdy "Mac" Mathias, Jr. (born July 24, 1922) is a Republican former member of the United States Senate, representing Maryland from 1969 to 1987. He was also a member of the Maryland House of Delegates from 1959 to 1960, and a member of the United States House of Representatives, representing the 6th congressional district of Maryland, from 1961 to 1969.

Born in Frederick, Maryland, Mathias attended Yale University and the University of Maryland School of Law, and served in the United States Navy during World War II. He worked as a lawyer, and was elected to the state legislature in 1958. In 1960, he was elected to the U.S. House of Representatives from Western Maryland. He served in the House for eight years, where he aligned himself with the then-influential liberal wing of the Republican Party.

Mathias was elected to the Senate in 1968, unseating Democrat Daniel Brewster. He continued his record as a liberal Republican in the Senate, and frequently clashed with the conservative wing of the party. For a few months in late 1975 and early 1976, Mathias ran an insurgent Presidential campaign in an attempt to stave off the increasing influence of conservative Republicans led by Ronald Reagan.

His confrontations with conservatives cost him several leadership positions in the Senate, including chairmanship of the Judiciary Committee. Despite isolation from his conservative colleagues, Mathis played an influential role in fostering African American civil rights, ending the Vietnam War, preserving the Chesapeake Bay, and constructing the Vietnam Veterans Memorial. He retired from the Senate in 1987, having served in Congress for 25 years. As of 2008, he is practicing law in Maryland.

Early life and career

Mathias was born in Frederick, Maryland, and attended Frederick County Public Schools. In 1944, he graduated from Haverford College in Pennsylvania. He later attended Yale University, and received a law degree from the University of Maryland School of Law in 1949.[1]

In 1942, during World War II, Mathias enlisted in the United States Navy and served at the rank of Seaman Apprentice. He was promoted to Ensign in 1944 and served sea duty in the Pacific Ocean from 1944 until he was released from active duty in 1946. Following the war, Mathias rose to the rank of Captain in the United States Naval Reserve.[1]

Mathias served as assistant Attorney General of Maryland from 1953 to 1954. From 1954 to 1959, he was the City Attorney of Frederick. In 1958, he was elected to the Maryland House of Delegates, serving from 1959 to 1960.[1]

Congressional career

On January 4, 1960, Mathias declared his candidacy for the House seat of Maryland's 6th congressional district.[2] He officially began his campaign in March, establishing public education and controlling government spending as two of his priorities should he be elected.[3] In the primary elections of May 1960, Mathias handily defeated his two rivals, garnering a 3-1 margin of victory.[4]

Mathias' opponent in the general election was John R. Foley, a former judge who had unseated DeWitt Hyde in a Democratic landslide in the state two years prior. Both candidates attacked each others' voting records, with Foley accusing Mathias of skipping more than 500 votes in the House of Delegates and having the "worse Republican record in Annapolis".[5] Mathias had previously accused Foley of voting "present" in the U.S. House too often, which he argued was leading to higher taxes and inflation due to inaction.[6] Mathias prevailed over Foley on election day in November 1960, unseating the one-term incumbent and becoming the first representative from Frederick County, Maryland since Milton Urner in 1883.[7]

During his eight year career in the House, Mathias established himself as a member of the liberal wing of the Republican Party, which was the most influential at the time.[8] He was the author of the "Mathias Amendment" to the unsuccessful 1966 civil rights bill, advocating open housing. Concerning environmental issues, Mathias sponsored legislation that made the Chesapeake & Ohio Canal a national park, and supported other conservation initiatives along the Potomac River.[9] He also served on the Judiciary Committee and the Committee on the District of Columbia.[10] As a member of the D.C. Committee, Mathias was a proponent of establishing home rule in the District of Columbia.[11]

United States Senate career

Election of 1968: unseating Brewster

Leading up to the United States Senate elections of 1968, Mathias' name was frequently mentioned as a potential challenger to Democratic incumbent Daniel Brewster. Representative Rogers Morton of Maryland's 1st congressional district was also considering a run at Brewster's seat, but was dissuaded by Republican party leaders in the state in favor of a Mathias candidacy. Their decision was largely due to the geography of Mathias' seat. As representative of the 6th district, he already had established name recognition in both the Baltimore and Washington, D.C. metropolitan areas, the more densely populated and liberal areas of the state. Mathias' seat was also more likely to stay under Republican control, unlike Morton's seat, which was located on the socially conservative but Democratic-voting Eastern Shore of Maryland. Mathias had also established a more liberal voting record, which was argued to serve him better in the state with a 3-1 ratio of Democrats to Republicans.[12]

Mathias officially declared his candidacy for Senate on February 10, 1968, calling for a reduction in the amount of forces in the Vietnam War, and identifying urban blight, racial discrimination, welfare reform, and improving public schools as major issues.[9] As the campaign drew on, the two primary issues became the War and criminal activity. Mathias argued that the extensive bombing campaigns in North Vietnam should be reduced, while Brewster had argued for increasing bombardment. Concerning law and order, Brewster adopted a hard line stance, while Mathias advocated addressing the precipiating causes of poverty and the low standard of living in urban ghettos. Personal and campaign finances were also made issues of the campaign, with Brewster causing controversy over the fact that $15,000 had been donated to his campaign by his Senate staff and their relatives.[10] On election day, November 5, 1968, Mathias defeated Brewster and perennial candidate George P. Mahoney. Mathias garnered 48% of the vote to Brewster's 39% and Mahoney's 13%.[13]

First term (1969-1975)

Mathias began his first term in the Senate in January 1969 and laid out his legislative agenda soon thereafter. On local issues, his priorities included establishing home rule in the District of Columbia and providing D.C. residents full representation in both chambers of Congress, two positions he carried over from his career in the House.[11]

Over the course of his first term, Mathias was frequently at odds with his conservative colleagues in the Senate and the Richard Nixon administration. In June 1969, Mathias joined with fellow liberal Republican Hugh Scott of Pennsylvania in threatening a "rebellion" unless the Nixon administration began to work harder to protect African American civil rights.[14] He also warned against a "Southern strategy" of attracting conservative George Wallace voters at the expense of moderate or liberal voters.[13] Concerning the Supreme Court, Mathias voted against two controversial Nixon nominees, Clement Haynsworth and G. Harrold Carswell, neither of whom were nominated by the rest of the Senate. Mathias was also an early advocate for setting a timetable for withdrawal of troops from Vietnam, and was against the bombing campaigns Nixon launched into Laos.[13] In October 1972, Mathias became the first Republican on Ted Kennedy's Judiciary subcommittee and one of only a few in the nation to support investigation into the Watergate Scandal surrounding Nixon, which was still in its early stages.[15]

Mathias' disagreements with the administration became well-known, causing columnists Rowland Evans and Robert Novak to name him the "new supervillain... in President Nixon's doghouse". Evans and Novak also commented that "not since [Charles Goodell] was defeated with White House connivance has any Republican so outraged Mr. Nixon and his senior staff as Mathias. The senator's liberalism and tendency to bolt party lines have bred animosity in the inner sanctum".[16] Due to their differing ideologies, there was speculation that Mathias was going to be "purged" from the party by Nixon in a similar manner as Goodell in 1971, but these threats disappeared after the Watergate scandal escalated. By the numbers, Mathias sided with the Nixon administration 47% of the time, and voted with his party 31% of the time during his first term.[13]

In early 1974, the group Americans for Democratic Action rated Mathias the most liberal member of the GOP in the Senate based on twenty key votes in the 1973 legislative session. At 90 percent, his score was higher than most Democrats in the Senate, and was fourth highest amongst all members. Issues considered when rating senators included their positions on civil rights, mass transit, D.C. home rule, tax reform, reducing overseas troop levels, and also their attendance.[17] The League of Women Voters gave Mathias a 100% on issues important to them, and the AFL-CIO agreed with Mathias on 32 out of 45 key labor votes. On the other end of the political spectrum, the Americans for Constitutional Action stated Mathias agreed with their positions only 16% of the time.[13]

Election of 1974: challenge from Mikulski

As a Republican representing heavily-Democratic Maryland, Mathias faced a potentially difficult re-election bid for the 1974 season. State Democrats nominated Barbara Mikulski, a councilwoman from Baltimore who was well-known to residents in her city as a social activist, but with limited name recognition throughout the rest of the state.[18] Mathias was renominated by Republicans, even though conservatives in Maryland frequently criticized his liberal voting record. His lack of competition was due in part to the fallout from the Watergate scandal.[13]

As an advocate for campaign finance reform, Mathias refused to accept any contribution over $100 to "avoid the curse of big money that has led to so much trouble in the last year".[19] However, he still managed to raise over $250,000, nearly five times that of Mikulski's campaign. Ideologically, Mikulski and Mathias agreed on many issues, such as closing tax loopholes and easing taxes on the middle class. However, they disagreed on how to address inflation and corporate price fixing, and Mathias argued more for reforming Congress and the U.S. tax system.[18] In retrospect, The Washington Post felt the election was "an intelligent discussion of state, national, and foreign affairs by two smart, well-informed people".[20]

With Maryland voters, Mathias benefited from his frequent disagreements with the Nixon administration and his liberal voting record. On November 5, 1974, he was re-elected by greater than a 10% margin, though he lost badly in Baltimore City and Baltimore County, where Mikulski was popular.[18]

Second term: conflict with conservatives (1975-1981)

Mathias expressed concerns with the state of his party leading up to the 1976 presidential election, specifically its shift further to the right. Referring to the nomination contest between Gerald Ford and Ronald Reagan, Mathias remarked that such an event would place the party leadership "in further isolation, in an extreme—almost fringe—position". On November 8, 1975, he hinted at entering some presidential primary elections to steer the party away from its strong conservative trend, should Reagan have won the 1976 New Hampshire primary.[21]

Mathias never campaigned aggressively, and was not taken seriously as a contender. Columnist George Will commented that Mathias was "contemplating a race—a stroll, really—for the presidency", in reference to his staid campaign.[22] After four months, Mathias decided in March 1976 to withdraw his name from the Massachusetts primary ballot to aid Ford. He had also been considering an independent bid, but said raising money would be too difficult under campaign finance laws. Upon his withdrawal, Mathias stated he would work with the Republican Party in the upcoming elections.[23] However, despite his pledge to support the Republican candidate, Mathias' criticism of the party did not wane, stating that "over and over again during the primaries, I have felt uncomfortably like a member of the chorus in a Greek tragedy".[24] In further criticism of his party neglecting liberal voters, Mathias commented:

I've had to deal with some hard truths... People don't like to hear we've got only 18 percent of the electorate. They pretend it's not important that our following among blacks, and young people, and urban communities is not what it should be... But I feel it's of the greatest importance that if there's to be a Republican Party, we look these facts in the face.[25]

Mathias' short candidacy did not endear himself to the conservative wing of Maryland Republicans. In June 1976, he lost in a vote by state Republicans to determine who would represent Maryland on the platform committee at the 1976 Republican National Convention. Instead, the group chose George Price, a conservative member of the Maryland House of Delegates from Baltimore County. At one point, Mathias was close to being denied attendance to the convention altogether as an at-large delegate.[24] Mathias maintained a low profile during the convention, and received harsh criticism from some of the conservative delegates from Maryland who attended.[25]

At the beginning of the new Congress in 1977, Mathias was in line for several potential committee promotions to ranking member. However, Mathias' outspoken criticism of the party in the previous election cycle aroused enmity amongst his colleagues. On the Judiciary Committee, Mathias had the most seniority of any other member except Strom Thurmond of South Carolina, who already held another ranking membership on the Armed Services Committee. Only one ranking membership was allowed per senator, so Thurmond resigned his ranking membership on the Armed Services Committee to circumvent Mathias serving as ranking member of the Judiciary Committee. Mathias was also prevented from assuming a leadership position on the Government Operations Committee, and on the Judiciary Subcommittee on Constitutional Rights. On the latter subcommittee, Mathias had more seniority than any other member. However, liberal Democrat Birch Bayh was chairman, and Mathias' party colleagues did not want to risk the possibility of the pair teaming up.[26]

After these slights, speculation was raised that Mathias could leave the Republican Party, especially as the 1980 elections were approaching. Conservatives in the state were considering challenging Mathias for his seat, such as Marjorie Holt or Robert Bauman, which could have resulted in a difficult primary battle for Mathias.[26] However, Mathias chose to remain as a Republican, and teamed up with eight other Republican senators to express their dissatisfaction with the hard-line wing of the party.[27] Though he had frequently been mentioned as a possible defector, Mathias later stated that he had never seriously considered leaving the Republican Party.[8]

When it came time to nominate members to the 1980 Republican National Convention, Maryland Republicans voted for Mathias and Bauman as co-chairman of the delegation to represent the liberal and conservative wings of the party, respectively. The 1980 nomination contest lacked the "fierce ideological bickering that marked the 1976 state convention", in which Mathias was nearly excluded as a delegate.[28]

Final term (1981-1987)

Mathias did not face any major opposition for his seat in 1980 from either party, and was re-elected by a substantial margin.[29] His Democratic counterpart, Edward T. Conroy, positioned himself as more conservative than Mathias. Conroy also made national defense the primary issue of his campaign, where he accused Mathias of being weak. Mathias countered, stating he had voted for over $1.1 trillion in defense spending during his career in the Senate.[20] By winning re-election, Mathias became the first Maryland Republican to win election to a third Senate term, and also the only Republican who won the city of Baltimore up to that point.[8]

After Republicans gained control of the Senate in 1981, Mathias sought the chairmanship of the Judiciary Committee but was relegated to the relatively mundane chairmanship of the Rules Committee.[8] He was also appointed chairman of the Government Operations Subcommittee on Government Efficiency and the District of Columbia, and accepted a seat on the influential Foreign Relations Committee, though he had to sacrifice his seat on the Appropriations Committee to do so.[30] In 1982, Mathias chaired a bipartisan Senate inquiry into the methods used by the FBI in the Abscam corruption investigation, which found that dozens of officials had been named for accepting bribes without basis.[31]

Leading up to the 1986 elections, it was unclear whether Mathias would seek a fourth term. His support of President Reagan was lukewarm, which had further isolated him ideologically from his Republican colleagues. One delegate at the Maryland state party convention had even called Mathias "liberal swine" for his independent record. Additionally, his frequent difficulties in securing a committee chairmanship along with his low attendance rate were raising questions regarding his effectiveness. However, Mathias was showing signs of seeking re-election in 1985, and dismissed any claims of ineffectiveness. Referring to the phone on his desk, Mathias claimed "within a matter of minutes, I can talk to any member of the Cabinet; and I could go see them within 24 hours... It was no accident that the Chesapeake Bay was mentioned in the President's State of the Union address. That took a lot of hard work".[32]

Despite initial indications otherwise, Mathias announced on September 27, 1985 that he would not seek a fourth term in the upcoming 1986 elections. His announcement concerned Republican party officials in the state, who feared that local Republicans had poorer election chances without Mathias at the top of the ticket. At the national level, Mathias' announcement came shortly after news that Republican Paul Laxalt of Nevada would be retiring as well. The departure of two Republican senators from Democratic-leaning states was treated by Republican party leaders as a poor sign of the party's chances in the upcoming elections.[33]

Mathias remained active in his final days in the Senate, playing an important role in removing a death penalty provision in a 1986 Senate drug bill after threatening filibuster, and in preparing impeachment proceedings against federal judge Harry E. Claiborne.[34] Mathias' last day in the Senate was January 3, 1987,[1] at which point he was succeeded by his 1974 challenger Barbara Mikulski.[35]

Political editorials

Mathias frequently contributed lengthy editorials to major newspapers, providing insight into his political priorities at the time. In his first editorial on December 2 1972 in The Washington Post, Mathias criticized the capability of Congress to conduct its duties:

The unfortunate fact is that, in relation not only to the other two branches of government but to the complex and critical problems that confront the nation and its people, the Congress has become, in far too many respects, an impotent and antiquated institution. The American people have, as a result, come to the regard the Executive as by far the most potent branch of government and to perceive the Congress as capable, at best, of exerting a negative check upon Executive power, of serving as a rather erratic obstacle course through which Executive proposals must pass.[36]

In making such criticisms, Mathias used the federal budget as an example. Though Congress had authority to approve or reject the budget, most of the allocations were made behind closed doors by subcommittees, with upwards of 40% of the budget bypassing the input of the Appropriations Committee at the time. Mathias called this occurrence one of the primary causes of increases in federal spending and, counterintuitively, decreases in taxes.[36]

On November 8, 1975, Mathias submitted to the Post excerpts from a speech he had recently made. In it, he criticizes both political parties for failing to resolve the issues that Americans were concerned about:

Americans are no longer willing to accept a political party as the lesser of evils. They are no longer willing to accept the old pol technique of never mentioning issues or of moving so fast that issues don't arise and contradictions can't be spotted. Nor will people continue to accept 30-second subliminal spots of daisies or giant saws cutting off the Eastern Seaboard. And they won't accept parties which have no vision for America. The pap that comes out of both National Committees is a fraud on their contributors. I have seldom been able to use any of it, and it would be a sad day if anyone was elected to a high public office who did.[37]

Specifically, Mathias states the political parties have "failed" to address: higher crime, unemployment, welfare reform, tax reform, bureaucratic reform, race relations, health care, and urban blight. According to Mathias, these problems were the cause of the exodus of Americans from both parties, and the significant increase of registered independents.[37]

Mathias expressed criticism of the construction of the United States-Mexican border fence on January 15, 1979:

Robert Frost's neighbor stubbornly maintained that "good fences make good neighbors". But Frost wasn't convinced. And neither am I. Some fences make bad blood, and we are building that kind of fence along the Rio Grande... There are no easy solutions, indeed there may be only partial solutions. But one thing is certain: The problem cannot be satisfactorily resolved by unilateral measures.[38]

In an editorial on January 18, 1983, Mathias urged Americans to support globalization rather than protectionism during the recession of the early 1980s. Mathias argued that the health of other countries would improve the livelihood of all Americans:

A national consensus must evolve in this country around the proposition that cooperation not confrontation is required if the world economy is to be rescued from its present unhappy state. This means that the unemployed worker in Baltimore, Chicago, or even Detroit, needs to see that his hope for a better future may lie in the restored economic health of countries as close as Mexico or as far away as Romania. That, in fact, their problems are our problems.[39]

In two editorials on October 16 and October 27, 1983, Mathias criticized U.S. foreign policy in Lebanon and Grenada, respectively. In both articles, Mathias attacks the policy of linkage advocated by the Reagan administration. Regarding Lebanon, Mathias expressed concern over the powers vested to the President, and over the involvement of both U.S. and Soviet Union forces: "by abandoning the traditional principle that peacekeeping forces should be drawn only from small neutral nations, the United States and the Soviet Union have loaded the dice against themselves, however justified this course may seem".[40] In the other editorial, Mathias was critical of actions leading up to the invasion of Grenada: "When the president acts precipitately, as he has in the case of Grenada, it destroys the possibilities of consensus and quite naturally opens the decision to divisive debate in Congress and the nation".[41]

Leading up to the 1984 Republican National Convention, Mathias scolded the Republican Party for ostracizing its moderate wing:

...Over the past few years the conservative strain has grown larger in the Republican Party, as it has in the country and even in the whole world. People yearn for simple answers as life becomes more complex. Simplistic rhetoric that has been offered by some Republicans has promised easy answers to complicated problems of modern life. That approach has had an appeal in the party, but it will not be ultimately satisfying, because life just is not simple... The Republican Party could not govern for any length of time without the injection of ideas on domestic and foreign policy that are brought to the party by its moderate members.[42]

Mathias was a frequent critic of the national deficit that had accumulated in the Reagan administration. In an editorial on April 30, 1985, Mathias asks Americans to sacrifice in order to preserve the financial integrity of the nation:

If we are serious about attacking the dangerous deficit... we must ask each American to be willing to make a sacrifice if that is necessary. We must put an end to the growth of our national debt, which has taken on a life of its own as larger and larger interest bills add to the total... While there is much spending we can reduce, there is also substantial revenue we can raise.[43]

Legacy, and post-Senate life

Mathias held a retirement party at the Baltimore Convention Center on July 14, 1986, which had over 1,200 attendees. The proceeds from the event, at $150 per person, were used to establish a foreign studies program at the Johns Hopkins University School of Advanced International Studies in his name. Mathias went on to teach at Johns Hopkins following his departure from the Senate.[44]

After his retirement, The Washington Post stated that Mathias' lasting reputation would be that of a maverick. Though he was elected to the House in 1960 as a moderate/conservative, his life in the Congress moved him to the center, and he frequently deviated from the party line and sided with Democrats. The fact that he "went out of his way to disassociate himself from [Ronald Reagan]" in the 1980 elections had hindered his chances at a chairmanship. Mathias also established a record on civil rights, having played an important role in passing a fair housing bill while he was in the House, and also in establishing a national holiday for Martin Luther King, Jr. He held liberal views on abortion, defense spending, and the Equal Rights Amendment[8], and, along with Senator John Warner of Virginia, was one of the sponsors of a bill to authorize the construction of the Vietnam Veterans Memorial.[44] In discussing Mathias' retirement, Tom Wicker of the The New York Times commented that "he was fair, flexible, concerned, able to rise above partisanship but not above responsibility". When Wicker asked him which senators he respected the most, Mathias listed J. William Fulbright, Jacob Javits, John Sherman Cooper, Cliff Case, Phil Hart, Mike Mansfield, and George Aiken, because "each one of those people would take an issue on his own responsibility... They'd simply come to the conclusion that this was the right thing for the country".[45]

On environmental issues, Mathias established a record as a strong advocate of the Chesapeake Bay. He sponsored legislation that led to a study by the EPA in 1975, which was one of the first reports that brought public attention to the harmful levels of nutrients and toxins in the Bay waters. The report was one of the catalysts for Bay cleanup efforts. In recognition, the Charles Mathias Laboratory, part of the Smithsonian Institution, was established in 1988 as a research facility to analyze human impact on the Bay.[46] In 1990, the Mathias Medal was established by Maryland Sea Grant at the University of Maryland Center for Environmental Science as further acknowledgment of Mathias' role in protecting the Bay.[47]

As of 2008, Mathias practices law in Washington, D.C. and is a resident of Chevy Chase, Maryland.[1]

References

- ^ a b c d e "Mathias, Charles McCurdy". United States Congress. Retrieved 2008-07-06.

- ^ "Mathias of Frederick Files For Foley's Seat". The Washington Post. January 5, 1960. p. A9.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ "Republican Candidate Begins Race". The Washington Post. March 13, 1960. p. B15.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ "Foley, Mathias Win in Maryland's Sixth". The Washington Post. May 18, 1960. p. A19.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ "Foley Assails Mathias On State Voting Record". The Washington Post. September 22, 1960. p. B3.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ "Foley Vote Record Hit By Mathias". The Washington Post. August 11, 1960. p. B5.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ Eisen, Jack (January 4, 1961). "Well-Wishers Inundate Mathias After he Takes Seat in Congress". The Washington Post. p. A4.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ a b c d e Baker, Donald P (September 29, 1985). "End of the Electoral Line for a Maryland Maverick". The Washington Post. p. C1.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ a b Barnes, Bart (February 11, 1968). "Mathias Runs for Senate". The Washington Post. p. A1.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ a b Homan, Richard (November 6, 1968). "Upsets in 2 Nearby States Divide House Seats Evenly". The Washington Post. p. A1.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ a b "Mathias to Introduce Home Rule Legislation". The Washington Post. January 20, 1969. p. C1.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ Eisen, Jack (January 2, 1968). "Mathias Points for Senate". The Washington Post. p. B1.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ a b c d e f Watson, Douglas (August 15, 1974). "Mathias Purge Threat Ends: White House Scandals Boost Senator's Re-election Bid". The Washington Post. p. C1.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ Rich, Spencer (June 28, 1969). "Conservative Trend Decried". The Washington Post. p. A1.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ Osnos, Peter (October 18, 1972). "GOP Senator Backs Sabotage Probe". The Washington Post. p. A19.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ Rowland, Evans (December 5, 1971). "Mathias: The New Goodell". The Washington Post. p. A2.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Rich, Spencer (January 7, 1974). "Liberal Unit Rates Senators; Mathias Is Highest in GOP". The Washington Post. p. A2.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ a b c Barker, Karlyn (November 6, 1974). "Mathias Is Elected To a Second Term". The Washington Post. p. A12.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ Richards, Bill (February 3, 1974). "Sen. Mathias Re-Election Drive Opens". The Washington Post. p. B1.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ a b "U.S. Senate Choice in Maryland". The Washington Post. October 22, 1980. p. A22.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ Baker, Donald P (November 9, 1975). "Mathias Says He May Run In Presidential Primaries". The Washington Post. p. 21.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ Will, George (January 25, 1976). "Sen. Mathias' 'Stroll'". The Washington Post. p. 131.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ Peterson, Bill (March 3, 1976). "Mathias Joins Almost-Rans, Will Not Seek Presidency". The Washington Post. p. A3.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ a b Peterson, Bill (June 26, 1976). "Dissident Mathias Denied GOP Platform Committee Post". The Washington Post. p. A5.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ a b Logan, Harold J (August 19, 1976). "Mathias' Convention Role Is Low-Key". The Washington Post. p. 14.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ a b Evans, Rowland (March 23, 1977). "The Republicans And Sen. Mathias". The Washington Post. p. A11.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Childs, Marquis (November 22, 1977). "Mathias's Bid to Save the GOP From Itself". United Feature Syndicate/The Washington Post. p. A19.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ Barringer, Felicity (June 2, 1980). "Md. Republicans' National Delegation Will Be Led by Mathias and Bauman". The Washington Post. p. B1.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ Baker, Donald P (November 5, 1980). "Mathias Crushes Underdog Challenger to Win Third Term in Senate". The Washington Post. p. A21.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ Baker, Donald P (December 4, 1980). "Mathias Agrees to Head Senate Rules Committee". The Washington Post. p. C5.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ Thornton, Mary (July 21, 1982). "Abscam Hearing Reveals 44 Were Unjustly Cited". The Washington Post. p. A4.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ Muscatine, Alison (July 9, 1984). "Mathias Swims Against the GOP's Tide". The Washington Post. p. B1.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ Sugawara, Sandra (September 28, 1985). "GOP's Mathias Says He Plans To Retire From Senate in '87". The Washington Post. p. A1.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ Greenhouse, Linda (October 6, 1986). "Still a Distinctive Voice, but Soon an Echo". The New York Times. p. B8.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ McQueen, Michel (November 5, 1986). "Schaefer, Mikulski Lead Democratic Sweep at the Top". The Washington Post. p. A1.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ a b Mathias, Charles McC. (December 4, 1972). "The Congress Is Not Doing Its Job". The Washington Post. p. A22.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ a b Mathias, Charles McC. (November 8, 1975). "Can the Political Parties Survive?". The Washington Post. p. A27.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ Mathias, Charles McC. (January 15, 1979). "Mending Fences with Mexico". The Washington Post. p. A21.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ Mathias, Charles McC. (January 18, 1983). "The World's Problems Are Our Problems...". The Washington Post. p. A17.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ Mathias, Charles McC. (October 16, 1983). "The Stakes in the Mideast Are Higher Than Ever". The Washington Post. p. B7.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ Mathias, Charles McC. (October 27, 1983). "Seeking Military Solutions". The Washington Post. p. A23.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ Mathias, Charles McC. (August 20, 1984). "Why Should a Moderate Go to Dallas?". The Washington Post. p. A17.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ Mathias, Charles McC. (April 30, 1985). "We Can Raise More Revenue". The Washington Post. p. A19.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ a b Kenworthy, Tom (July 15, 1986). "Sendoff for a Senator, 1,200 Honor Mathias on His Retirement". The Washington Post. p. B1.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) Cite error: The named reference "Kenworthy-28Sept1985" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page). - ^ Wicker, Tom (November 16, 1986). "A Good Man Going". The New York Times. p. E23.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ Rutherford, Anne (November 26, 1987). "Environment Lab Named For Mathias". The Washington Post. p. 244.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ "Mathias Medal". Maryland Sea Grant. Retrieved 2008-07-05.

External links

- Mathias Medal by the Maryland Sea Grant at the University of Maryland Center for Environmental Science

- Dedication along Interstate 270 in Maryland.

- 1922 births

- Living people

- American military personnel of World War II

- Maryland lawyers

- Members of the Maryland House of Delegates

- Members of the United States House of Representatives from Maryland

- United States Navy officers

- United States Senators from Maryland

- University of Maryland, Baltimore alumni

- People from Frederick County, Maryland

- Maryland Republicans

- Liberal politicians

- Congressional opponents of the Vietnam War