Makemake

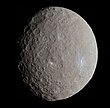

Artist's conception of Makemake, by Ann Feild (Space Telescope Science Institute) | |

| Discovery | |

|---|---|

| Discovered by | Michael E. Brown, Chad Trujillo, David Rabinowitz |

| Discovery date | March 31 2005 |

| Designations | |

Designation | (136472) Makemake |

| 2005 FY9 | |

| TNO | |

| Orbital characteristics[1][2] | |

| Epoch January 28 1955 (JD 2435135.5) | |

| Aphelion | 7,939.7 Gm (53.074 AU) |

| Perihelion | 5,760.8 Gm (38.509 AU) |

| 6,850.3 Gm (45.791 AU) | |

| Eccentricity | 0.159 |

| 113,183 d (309.88 a) | |

Average orbital speed | 4.419 km/s |

| 85.13° | |

| Inclination | 28.96 ° |

| 79.382° | |

| 298.41° | |

| Physical characteristics | |

| Dimensions | 1,300–1,900 km |

| 750+200 −100 km[3] | |

| ~7,000,000 km² | |

| Volume | ~1.8 km³ |

| Mass | ~4 kg |

Mean density | ~2 g/cm³ |

| ~0.5 m/s² | |

| ~0.8 km/s | |

| Albedo | 78.2+10.3 −8.6 (geometric)[3] |

| Temperature | ~30 K (−243 °C; −406 °F) |

| 16.7 (opposition)[4] | |

| −0.48[2] | |

Makemake (pronounced [5]), formally designated (136472) Makemake, is the third-largest known dwarf planet in the Solar System and one of the two largest Kuiper belt objects (KBO) in the classical KBO population.[6] Its diameter is roughly three-quarters that of Pluto.[7] Makemake has no known satellites, which makes it unique among the largest KBOs. Its extremely low average temperature (about 30 K) means its surface is covered with methane and possibly ethane ices.[8]

Initially known as 2005 FY9 (and later given the minor planet number 136472), it was discovered on March 31, 2005 by a team led by Michael Brown. Its discovery was announced on July 29, 2005. On June 11, 2008, the IAU included Makemake in its list of potential candidates to be given "plutoid" status, a term for dwarf planets beyond the orbit of Neptune that would place the object alongside Pluto and Eris. Makemake was formally classified as a plutoid in July 2008.[9][10][11][12]

Discovery

Makemake was discovered on March 31, 2005 by a team led by Michael Brown.[2] Its discovery was announced on July 29, 2005, which was the same day as Eris and two days after 2003 EL61.[13]

Despite its relative brightness, 16.7 magnitude vs. 15 for Pluto, Makemake was not discovered until well after many much fainter Kuiper belt objects. This is probably due to its relatively high orbital inclination and the fact that it was at its farthest distance from the ecliptic (the region of the sky that the Sun, Moon and planets appear to lie in, as seen from Earth) at the time of its discovery (in the northern constellation of Coma Berenices).[4] Most searches for minor planets are conducted relatively close to the ecliptic, due to the greater probability of finding objects there.

Makemake is the only other dwarf planet that was bright enough for Clyde Tombaugh to have possibly detected during his search for Pluto.[14] At the time of Tombaugh's survey, Makemake was only a few degrees from the ecliptic, near the border of Taurus and Auriga,[15] at an apparent magnitude of 16.0.[4] This position, however, was also very near the Milky Way, making it almost impossible to find within the dense concentration of background stars. Tombaugh continued searching for some years after the discovery of Pluto,[16] but he failed to find Makemake or any other trans-Neptunian objects.

Name

The designation 2005 FY9 was given to Makemake when the discovery was made public. Before that, the discovery team used the codename "Easterbunny" for the object because of the discovery time shortly after Easter.[17]

In July 2008, in accordance with IAU rules for classical Kuiper belt objects, 2005 FY9 was given the name of a creator deity. The name of Makemake, the creator of humanity in the mythos of the Rapanui, the native people of Easter Island,[9] was chosen in part to preserve the object's connection with Easter.[17]

Physical characteristics

Size and brightness

Makemake is currently visually the second brightest Kuiper belt object after Pluto,[14] having a March opposition apparent magnitude of about 16.7 in the constellation Coma Berenices.[4] This is bright enough to be visible using a high-end amateur telescope. Makemake's high albedo of roughly 80 percent suggests an average surface temperature of roughly 30 K.[18][3] The size of Makemake is not precisely known, but the detection in infrared by the Spitzer space telescope, combined with the similarities of spectrum with Pluto yielded an estimate of a 1,500+400

−200 km diameter.[3] This is slightly larger than the size of 2003 EL61 making Makemake the third largest known Trans-Neptunian object after Eris and Pluto.[19][20] Makemake is now designated the fourth dwarf planet in the Solar System since it has a bright absolute magnitude of −0.48[2], practically guaranteeing that it is large enough to achieve hydrostatic equilibrium.[9]

Error: Image is invalid or non-existent.

Spectra

In a letter written to the journal Astronomy and Astrophysics in 2006, Licandro et al. showed that the surface of Makemake resembles that of Pluto by measuring its visible and near infrared spectrum using the William Herschel Telescope and Telescopio Nazionale Galileo.[21] It appears red in the visible spectrum, as opposed to, for example, Eris which has a neutral spectrum (see colour comparison for TNOs).[21] The infrared spectrum is marked by the presence of methane (CH4), as also observed on Pluto and Eris. Its presence, more prominent even than on Pluto, suggests that Makemake could have a transient atmosphere similar to Pluto's near perihelion.[21]

Spectral analysis of Makemake's surface also reveals evidence of large-grained methane crystals, at least one centimetre in diameter, along with large amounts of ethane, most likely created by photolysis of methane from solar radiation.[8] Although evidence exists for the presence of nitrogen ice on its surface, at least mixed with other substances, there is nowhere near the same level of nitrogen as exists on Pluto, where it comprises more than 98 percent of the crust. The lack of nitrogen ice suggests that its supply of nitrogen has somehow been depleted over the age of the Solar System.[8][22][23]

Orbit

As of 2008, Makemake is at a distance of 52 AU from the Sun;[4] almost as far from the Sun as it ever reaches in its orbit.[8] Makemake follows an orbit very similar to that of 2003 EL61: highly inclined (29°) and moderately eccentric (e~0.15).[24] Nevertheless, Makemake's orbit is slightly farther from the Sun (in terms of both the semi-major axis and perihelion). Its orbital period is nearly 310 years,[1] more than Pluto's 248 years.

The diagram below shows the similar orbits of the two objects contrasted with the orbit of Pluto. The perihelia (q)[2] and the aphelia (Q) are marked with the dates of passage. The positions on April 2006 are marked with the spheres illustrating relative sizes and differences in albedo and colour. Both are currently far above the ecliptic (illustrated as Neptune's orbit in grey). Makemake is approaching its 2033 aphelion,[4] while 2003 EL61 passed its aphelion in late 1991.[25]

Satellites

No satellites have been detected around Makemake to a radius of 0.4 arcseconds with a brightness more than one percent of the primary.[14] This contrasts with the other largest trans-Neptunian objects, which all possess at least one satellite: Eris has one, 2003 EL61 has two and Pluto has three. From 10% to 20% of all trans-Neptunian objects are expected to have one or more satellites.[14] Since satellites offer a simple method to measure an object's mass, lack of a satellite makes obtaining an accurate figure for Makemake's mass more difficult.[14]

Classification

Makemake is classified a classical Kuiper belt object,[26][6] which means it lies in the region of the belt (between 42 and 48 AU) gravitationally unaffected by the orbit of Neptune.[27][28] Unlike plutinos, which can cross Neptune's orbit due to their 2:3 resonance with the planet, the classical objects have perihelia further from the Sun, free from Neptune’s perturbation.[28] Such objects have relatively low eccentricities and orbit the Sun in much the same way the planets do. Makemake, however, is a member of the "dynamically hot" class of classical KBOs, meaning that it has a high inclination compared to others in its population.[29]

On August 24, 2006, the International Astronomical Union (IAU) announced a formal definition of planet that established a tripartite classification for objects in orbit around the Sun: "small Solar System bodies" were those objects too small for their gravity to have collapsed their surfaces into a rounded shape; "dwarf planets" were those objects large enough to be rounded, but who had yet to clear their orbits of similar-sized objects; "planets" were those objects that were both large enough to be rounded by self-gravity and which had cleared their orbits of similar-sized objects.[30] Under this classification, Pluto, Eris and Ceres were reclassified as dwarf planets.[30]

On June 11, 2008, the IAU further elaborated on this classification scheme by creating a subclass of dwarf planet, plutoid, specifically for those dwarf planets found beyond the orbit of Neptune. Eris and Pluto are thus plutoids, while Ceres is not. To be considered a plutoid, an object must be exceptionally bright with an absolute magnitude of H= +1,[31] which meant that only Makemake and 2003 EL61 are likely to be included.[32] On July 11, 2008, the IAU/USGS Working Group on Planetary Nomenclature included Makemake in the plutoid class, making it officially both a dwarf planet and a plutoid, alongside Pluto and Eris.[9][12]

References

- ^ a b Marc W. Buie (2008/04/05). "Orbit Fit and Astrometric record for 136472". SwRI (Space Science Department). Retrieved 2008-07-13.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ a b c d e "JPL Small-Body Database Browser: 136472 (2005 FY9)". 2008-04-05 last obs. Retrieved 2008-06-11.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ a b c d Stansberry, J. (2007). "Physical Properties of Kuiper Belt and Centaur Objects: Constraints from Spitzer Space Telescope" (abstract).

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c d e f "HORIZONS Web-Interface". JPL Solar System Dynamics. Retrieved 2008-07-01.

{{cite web}}: External link in|publisher= - ^ Craig, Robert D. (2004). Handbook of Polynesian Mythology. pp. p63. ISBN 1576078949. Retrieved 2008-07-14.

{{cite book}}:|pages=has extra text (help) - ^ a b Astronomers Mike Brown, David Jewitt and Marc Buie classify Makemake as a near scattered object but the Minor Planet Center, from which Wikipedia draws most of its definitions for the trans-Neptunian population, places it among the main Kuiper belt population.

- ^ Michael E. Brown (2006). "The discovery of 2003 UB313 Eris, the 10th planet largest known dwarf planet". CalTech. Retrieved 2008-07-14.

- ^ a b c d Mike Brown, K. M. Barksume, G. L. Blake; et al. (2007). "Methane and Ethane on the Bright Kuiper Belt Object 2005 FY9". The Astronomical Journal. 133: 284–289. doi:10.1086/509734. Retrieved 2008-07-14.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c d "Dwarf Planets and their Systems". Working Group for Planetary System Nomenclature (WGPSN). 07/11/2008 11:42:58. Retrieved 2008-07-13.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Tancredi, Gonzalo (2008). "Which are the dwarfs in the Solar System?". Icarus. 195 (2): 851–862. doi:10.1016/j.icarus.2007.12.020.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Brown, Michael E. "The Dwarf Planets". California Institute of Technology, Department of Geological Sciences. Retrieved 2008-01-26.

- ^ a b International Astronomical Union (July 19, 2008). "News Release - IAU0806: Fourth dwarf planet named Makemake". Retrieved 2008-07-20.

- ^ Thomas H. Maugh II and John Johnson Jr. (2005). "His Stellar Discovery Is Eclipsed". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 2008-07-14.

- ^ a b c d e M. E. Brown, M. A. van Dam, A. H. Bouchez; et al. (2006). "Satellites of the Largest Kuiper Belt Objects" (PDF). The Astrophysical Journal. 639: 43–46. doi:10.1086/501524. Retrieved 2008-07-14.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Based on Minor Planet Center online Minor Planet Ephemeris Service: March 1 1930: RA: 05h51m, Dec: +29.0

- ^ "Clyde W. Tombaugh". New Mexico Museum of Space History. Retrieved 2008-06-29.

- ^ a b Mike Brown (2008). "Mike Brown's Planets: What's in a name? [part 2]". CalTech. Retrieved 2008-07-14.

- ^ Calculated using the formula

where Teff =54.8 K, =0.78 is the geometrical albedo, q=0.8 is the phase integral. All parameters are taken from Stansberry, et al, 2007. - ^ Tegler, S. C. (2007). "Optical Spectroscopy of the Large Kuiper Belt Objects 136472 (2005 FY9) and 136108 (2003 EL61)". The Astronomical Journal. 133: 526–530. doi:10.1086/510134.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ "Dwarf planet". Retrieved 2007-05-31.

- ^ a b c J. Licandro, N. Pinilla-Alonso, M. Pedani; et al. (2006). "The methane ice rich surface of large TNO 2005 FY9: a Pluto-twin in the trans-neptunian belt?". Astronomy and Astrophysics. 445 (L35–L38): L35. doi:10.1051/0004-6361:200500219. Retrieved 2008-07-14.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ S.C. Tegler, W.M. Grundy, F. Vilas; et al. (June 2008). "Evidence of N2-ice on the surface of the icy dwarf Planet 136472 (2005 FY9)". Icarus. 195 (2): 844–850. doi:10.1016/j.icarus.2007.12.015. Retrieved 2008-07-21.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Tobias C. Owen, Ted L. Roush; et al. (1993). "Surface Ices and the Atmospheric Composition of Pluto". Science. 261 (5122): 745–748. doi:10.1126/science.261.5122.745. PMID 17757212. Retrieved 2007-03-29.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ S. C. Tegler; et al. (2007). "Optical Spectroscopy of the Large Kuiper Belt Objects 136472 (2005 FY9) and 136108 (2003 EL61)". The Astronomical Journal. 133: 526–530. doi:10.1086/510134. Retrieved 2008-07-14.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help) - ^ "Horizons 2003EL61". JPL Solar System Dynamics. Retrieved 2008-07-14.

- ^ "Minor Planet Electronic Circular 2006-X45: Distant Minor Planets". Minor Planet Center. 2006 Dec. 21. Retrieved 2008-07-21.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Jonathan Lunine (2003). "The Kuiper Belt" (pdf). Retrieved 2007-06-23.

- ^ a b David Jewitt (2004). "Classical Kuiper Belt Objects (CKBOs)". Retrieved 2007-06-23.

- ^ Harold F. Levison, Alessandro Morbidelli (2003). "The formation of the Kuiper belt by the outward transport of bodies during Neptune's migration" (pdf). Retrieved 2007-06-25.

- ^ a b "IAU 2006 General Assembly: Result of the IAU Resolution votes" (Press release). International Astronomical Union (News Release - IAU0603). 2006-08-24. Retrieved 2007-12-31. (orig link)

- ^ "Plutoid chosen as name for Solar System objects like Pluto". International Astronomical Union (News Release - IAU0804). 2008-06-11, Paris. Retrieved 2008-06-11.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Michael Brown (2008). "Mike Brown's Planets:Plutoid fever". Retrieved 2008-07-14.

External links

- MPEC listing for Makemake

- AstDys orbital elements

- Orbital simulation from JPL (Java) / Ephemeris

- Press release from WHT and TNG on Makemake's similarity to Pluto.

- Makemake chart and Orbit Viewer

- Precovery image with the 1.06 m Kleť Observatory telescope on 2003 April 20

- Makemake of the Outer Solar System APOD July 15, 2008