Photography

This article needs additional citations for verification. (October 2008) |

Photography (Template:Pron-en[1]) (from Greek φωτο and γραφία) is the process, activity and art of creating still or moving pictures by recording radiation on a sensitive medium, such as a film, or an electronic sensor. Light patterns reflected or emitted from objects activate a sensitive chemical or electronic sensor during a timed exposure, usually through a photographic lens in a device known as a camera that also stores the resulting information chemically or electronically. Photography has many uses for business, science, art and pleasure.

The word "photography" comes from the Greek φώς (phos) "light" + γραφίς (graphis) "stylus", "paintbrush" or γραφή (graphê) "representation by means of lines" or "drawing", together meaning "drawing with light." Traditionally, the products of photography have been called negatives and photographs, commonly shortened to photos.

The discipline of making lighting and camera choices when recording photographic images for the cinema is dealt with under Cinematography

Function

The camera or camera obscura is the image-forming device, and photographic film or a silicon electronic image sensor is the sensing medium. The respective recording medium can be the film itself, or a digital electronic or magnetic memory.

Photographers control the camera and lens to "expose" the light recording material (such as film) to the required amount of light to form a "latent image" (on film) or "raw file" (in digital cameras) which, after appropriate processing, is converted to a usable image. Digital cameras replace film with an electronic image sensor based on light-sensitive electronics such as charge-coupled device (CCD) or complementary metal-oxide-semiconductor (CMOS) technology. The resulting digital image is stored electronically, but can be reproduced on paper or film.

The movie camera is a type of photographic camera which takes a rapid sequence of photographs on strips of film. In contrast to a still camera, which captures a single snapshot at a time, the movie camera takes a series of images, each called a "frame". This is accomplished through an intermittent mechanism. The frames are later played back in a movie projector at a specific speed, called the "frame rate" (number of frames per second). While viewing, a person's eyes and brain merge the separate pictures together to create the illusion of motion.[2]

In all but certain specialized cameras, the process of obtaining a usable exposure must involve the use, manually or automatically, of a few controls to ensure the photograph is clear, sharp and well illuminated. The controls usually include but are not limited to the following:

- Focus - the adjustment to place the sharpest focus where it is desired on the subject.

- Aperture – adjustment of the iris, measured as f-number, which controls the amount of light passing through the lens. Aperture also has an effect on focus and depth of field, namely, the smaller the opening aperture, the less light but the greater the depth of field--that is, the greater the range within which objects appear to be sharply focused. The current focal length divided by the f-number gives the actual aperture size in millimeters.

- Shutter speed – adjustment of the speed (often expressed either as fractions of seconds or as an angle, with mechanical shutters) of the shutter to control the amount of time during which the imaging medium is exposed to light for each exposure. Shutter speed may be used to control the amount of light striking the image plane; 'faster' shutter speeds (that is, those of shorter duration) decrease both the amount of light and the amount of image blurring from motion of the subject and/or camera.

- White balance – on digital cameras, electronic compensation for the color temperature associated with a given set of lighting conditions, ensuring that white light is registered as such on the imaging chip and therefore that the colors in the frame will appear natural. On mechanical, film-based cameras, this function is served by the operator's choice of film stock or with color correction filters. In addition to using white balance to register natural coloration of the image, photographers may employ white balance to aesthetic end, for example white balancing to a blue object in order to obtain a warm color temperature.

- Metering – measurement of exposure so that highlights and shadows are exposed according to the photographer's wishes. Many modern cameras meter and set exposure automatically. Before automatic exposure, correct exposure was accomplished with the use of a separate light metering device or by the photographer's knowledge and experience of gauging correct settings. To translate the amount of light into a usable aperture and shutter speed, the meter needs to adjust for the sensitivity of the film or sensor to light. This is done by setting the "film speed" or ISO sensitivity into the meter.

- ISO speed – traditionally used to "tell the camera" the film speed of the selected film on film cameras, ISO speeds are employed on modern digital cameras as an indication of the system's gain from light to numerical output and to control the automatic exposure system. A correct combination of ISO speed, aperture, and shutter speed leads to an image that is neither too dark nor too light.

- Auto-focus point – on some cameras, the selection of a point in the imaging frame upon which the auto-focus system will attempt to focus. Many Single-lens reflex cameras (SLR) feature multiple auto-focus points in the viewfinder.

Many other elements of the imaging device itself may have a pronounced effect on the quality and/or aesthetic effect of a given photograph; among them are:

- Focal length and type of lens (telephoto or "long" lens, macro, wide angle, fisheye, or zoom)

- Filters placed between the subject and the light recording material, either in front of or behind the lens

- Inherent sensitivity of the medium to light intensity and color/wavelengths.

- The nature of the light recording material, for example its resolution as measured in pixels or grains of silver halide.

Exposure and rendering

Camera controls are inter-related. The total amount of light reaching the film plane (the "exposure") changes with the duration of exposure, aperture of the lens, and, the effective focal length of the lens (which in variable focal length lenses, can change as the lens is zoomed). Changing any of these controls can alter the exposure. Many cameras may be set to adjust most or all of these controls automatically. This automatic functionality is useful for occasional photographers in many situations.

The duration of an exposure is referred to as shutter speed, often even in cameras that don't have a physical shutter, and is typically measured in fractions of a second. Aperture is expressed by an f-number or f-stop (derived from focal ratio), which is proportional to the ratio of the focal length to the diameter of the aperture. If the f-number is decreased by a factor of , the aperture diameter is increased by the same factor, and its area is increased by a factor of 2. The f-stops that might be found on a typical lens include 2.8, 4, 5.6, 8, 11, 16, 22, 32, where going up "one stop" (using lower f-stop numbers) doubles the amount of light reaching the film, and stopping down one stop halves the amount of light.

Exposures can be achieved through various combinations of shutter speed and aperture. For example, f/8 at 8 ms (=1/125th of a second) and f/5.6 at 4 ms (=1/250th of a second) yield the same amount of light. The chosen combination has an impact on the final result. In addition to the subject or camera movement that might vary depending on the shutter speed, the aperture (and focal length of the lens) determine the depth of field, which refers to the range of distances from the lens that will be in focus. For example, using a long lens and a large aperture (f/2.8, for example), a subject's eyes might be in sharp focus, but not the tip of the nose. With a smaller aperture (f/22), or a shorter lens, both the subject's eyes and nose can be in focus. With very small apertures, such as pinholes, a wide range of distance can be brought into focus.

Image capture is only part of the image forming process. Regardless of material, some process must be employed to render the latent image captured by the camera into the final photographic work. This process consists of two steps, development and printing.

During the printing process, modifications can be made to the print by several controls. Many of these controls are similar to controls during image capture, while some are exclusive to the printing process. Most controls have equivalent digital concepts, but some create different effects. For example, dodging and burning controls are different between digital and film processes. Other printing modifications include:

- Chemicals and process used during film development

- Duration of exposure – equivalent to shutter speed

- Printing aperture – equivalent to aperture, but has no effect on depth of field

- Contrast - changing the visual properties of objects in an image to make them distinguishable from other objects and the background

- Dodging – reduces exposure of certain print areas, resulting in lighter areas

- Burning in – increases exposure of certain areas, resulting in darker areas

- Paper texture – glossy, matte, etc

- Paper type – resin-coated (RC) or fiber-based (FB)

- Paper size

- Toners – used to add warm or cold tones to black and white prints

Uses

Photography gained the interest of many scientists and artists from its inception. Scientists have used photography to record and study movements, such as Eadweard Muybridge's study of human and animal locomotion in 1887. Artists are equally interested by these aspects but also try to explore avenues other than the photo-mechanical representation of reality, such as the pictorialist movement. Military, police, and security forces use photography for surveillance, recognition and data storage. Photography is used by amateurs to preserve memories of favorite times, to capture special moments, to tell stories, to send messages, and as a source of entertainment. Many mobile phones now contain cameras to facilitate such use.

Commercial advertising relies heavily on photography and has contributed greatly to its development.

History

Photography is the result of combining several technical discoveries. Long before the first photographs were made, Chinese philosopher Mo Ti described a pinhole camera in the 5th century B.C.E,[3] Ibn al-Haytham (Alhazen) (965–1040) studied the camera obscura and pinhole camera,[3][4] Albertus Magnus (1193–1280) discovered silver nitrate, and Georges Fabricius (1516–1571) discovered silver chloride.[citation needed] Daniel Barbaro described a diaphragm in 1568.[citation needed] Wilhelm Homberg described how light darkened some chemicals (photochemical effect) in 1694.[citation needed] The fiction book Giphantie, by French author Tiphaigne de la Roche, described what can be interpreted as photography.[citation needed]

Photography as a usable process goes back to the 1820s with the development of chemical photography. The first permanent photograph was an image produced in 1825 by the French inventor Nicéphore Niépce. However, because his photographs took so long to expose, he sought to find a new process. Working in conjunction with Louis Daguerre, they experimented with silver compounds based on a Johann Heinrich Schultz discovery in 1724 that a silver and chalk mixture darkens when exposed to light. Niépce died in 1833, but Daguerre continued the work, eventually culminating with the development of the daguerreotype in 1837. Daguerre took the first ever photo of a person in 1839 when, while taking a daguerreotype of a Paris street, a pedestrian stopped for a shoe shine, long enough to be captured by the long exposure (several minutes). Eventually, France agreed to pay Daguerre a pension for his formula, in exchange for his promise to announce his discovery to the world as the gift of France, which he did in 1839.

Meanwhile, Hercules Florence had already created a very similar process in 1832, naming it Photographie, and William Fox Talbot had earlier discovered another means to fix a silver process image but had kept it secret. After reading about Daguerre's invention, Talbot refined his process so that portraits were made readily available to the masses. By 1840, Talbot had invented the calotype process, which creates negative images. John Herschel made many contributions to the new methods. He invented the cyanotype process, now familiar as the "blueprint". He was the first to use the terms "photography", "negative" and "positive". He discovered sodium thiosulphate solution to be a solvent of silver halides in 1819, and informed Talbot and Daguerre of his discovery in 1839 that it could be used to "fix" pictures and make them permanent. He made the first glass negative in late 1839.

In March 1851, Frederick Scott Archer published his findings in "The Chemist" on the wet plate collodion process. This became the most widely used process between 1852 and the late 1880s when the dry plate was introduced. There are three subsets to the Collodion process; the Ambrotype (positive image on glass), the Ferrotype or Tintype (positive image on metal) and the negative which was printed on Albumen or Salt paper.

Many advances in photographic glass plates and printing were made in through the nineteenth century. In 1884, George Eastman developed the technology of film to replace photographic plates, leading to the technology used by film cameras today.

In 1908 Gabriel Lippmann won the Nobel Laureate in Physics for his method of reproducing colors photographically based on the phenomenon of interference, also known as the Lippmann plate.

Processes

Black-and-white

All photography was originally monochrome, most of these photographs were black-and-white. Even after color film was readily available, black-and-white photography continued to dominate for decades, due to its lower cost and its "classic" photographic look. It is important to note that some monochromatic pictures are not always pure blacks and whites, but also contain other hues depending on the process. The Cyanotype process produces an image of blue and white for example. The albumen process which was used more than 150 years ago had brown tones.

Many photographers continue to produce some monochrome images. Some full color digital images are processed using a variety of techniques to create black and whites, and some cameras have even been produced to exclusively shoot monochrome.

Color

Color photography was explored beginning in the mid 1800s. Early experiments in color could not fix the photograph and prevent the color from fading. The first permanent color photo was taken in 1861 by the physicist James Clerk Maxwell.

One of the early methods of taking color photos was to use three cameras. Each camera would have a color filter in front of the lens. This technique provides the photographer with the three basic channels required to recreate a color image in a darkroom or processing plant. Russian photographer Sergei Mikhailovich Prokudin-Gorskii developed another technique, with three color plates taken in quick succession.

Practical application of the technique was held back by the very limited color response of early film; however, in the early 1900s, following the work of photo-chemists such as H. W. Vogel, emulsions with adequate sensitivity to green and red light at last became available.

The first color plate, Autochrome, invented by the French Lumière brothers, reached the market in 1907. It was based on a 'screen-plate' filter made of dyed dots of potato starch, and was the only color film on the market until German Agfa introduced the similar Agfacolor in 1932. In 1935, American Kodak introduced the first modern ('integrated tri-pack') color film which was developed by Polish constructor Jan Szczepanik. It was Kodachrome, based on three colored emulsions. This was followed in 1936 by Agfa's Agfacolor Neue. Unlike the Kodachrome tri-pack process, the color couplers in Agfacolor Neue were integral with the emulsion layers, which greatly simplified the film processing. Most modern color films, except Kodachrome, are based on the Agfacolor Neue technology. Instant color film was introduced by Polaroid in 1963.

Color photography may form images as a positive transparency, intended for use in a slide projector, or as color negatives intended for use in creating positive color enlargements on specially coated paper. The latter is now the most common form of film (non-digital) color photography owing to the introduction of automated photoprinting equipment.

Full-spectrum, ultraviolet and infrared

Ultraviolet and infrared films have been available for many decades and employed in a variety of photographic avenues since the 1960s. New technological trends in digital photography have opened a new direction in full spectrum photography, where careful filtering choices across the ultraviolet, visible and infrared lead to new artistic visions.

Modified digital cameras can detect some ultraviolet, all of the visible and much of the near infrared spectrum, as most digital imaging sensors are sensitive from about 350 nm to 1000 nm. An off-the-shelf digital camera contains an infrared hot mirror filter that blocks most of the infrared and a bit of the ultraviolet that would otherwise be detected by the sensor, narrowing the accepted range from about 400 nm to 700 nm[5]. Replacing a hot mirror or infrared blocking filter with an infrared pass or a wide spectrally transmitting filter allows the camera to detect the wider spectrum light at greater sensitivity. Without the hot-mirror, the red, green and blue (or cyan, yellow and magenta) colored micro-filters placed over the sensor elements pass varying amounts of ultraviolet (blue window) and infrared (primarily red, and somewhat lesser the green and blue micro-filters).

Uses of full spectrum photography are for fine art photography, geology, forensics & law enforcement, and even some claimed use in ghost hunting.

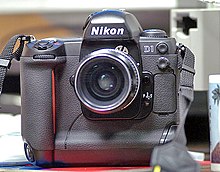

Digital

Traditional photography burdened photographers working at remote locations without easy access to processing facilities, and competition from television pressured photographers to deliver images to newspapers with greater speed. Photo journalists at remote locations often carried miniature photo labs and a means of transmitting images through telephone lines. In 1981, Sony unveiled the first consumer camera to use a charge-coupled device for imaging, eliminating the need for film: the Sony Mavica. While the Mavica saved images to disk, the images were displayed on television, and the camera was not fully digital. In 1990, Kodak unveiled the DCS 100, the first commercially available digital camera. Although its high cost precluded uses other than photojournalism and professional photography, commercial digital photography was born.

Digital imaging uses an electronic image sensor to record the image as a set of electronic data rather than as chemical changes on film. The primary difference between digital and chemical photography is that chemical photography resists manipulation because it involves film and photographic paper, while digital imaging is a highly manipulative medium. This difference allows for a degree of image post-processing that is comparatively difficult in film-based photography and permits different communicative potentials and applications.

Digital point-and-shoot cameras have become widespread consumer products, outselling film cameras, and including new features such as video and audio recording. Kodak announced in January 2004 that it would no longer sell reloadable 35 mm cameras in western Europe, Canada and the United States after the end of that year. Kodak was at that time a minor player in the reloadable film cameras market. In January 2006, Nikon followed suit and announced that they will stop the production of all but two models of their film cameras: the low-end Nikon FM10, and the high-end Nikon F6. On May 25, 2006, Canon announced they will stop developing new film SLR cameras.[6] Though most new camera designs are now digital, a new 6x6cm/6x7cm medium format film camera was introduced in 2008 in a cooperation between Fuji and Voigtländer.[7][8]

According to a survey made by Kodak in 2007, 75 percent of professional photographers say they will continue to use film, even though some embrace digital.[9]

According to the U.S. survey results, more than two-thirds (68 percent) of professional photographers prefer the results of film to those of digital for certain applications including:

- film’s superiority in capturing more information on medium and large format films (48 percent);

- creating a traditional photographic look (48 percent);

- capturing shadow and highlighting details (45 percent);

- the wide exposure latitude of film (42 percent); and

- archival storage (38 percent)

Digital imaging has raised many ethical concerns because of the ease of manipulating digital photographs in post processing. Many photojournalists have declared they will not crop their pictures, or are forbidden from combining elements of multiple photos to make "illustrations," passing them as real photographs. Today's technology has made picture editing relatively simple for even the novice photographer. However, recent changes of in-camera processing allows digital fingerprinting of RAW photos to verify against tampering of digital photos for forensics use.

Camera phones, combined with sites like flickr, have lead to a new kind of social photography.

Modes of production

Amateur

An amateur photographer is one who practices photography as a hobby and not for profit. The quality of some amateur work is comparable or superior to that of many professionals and may be highly specialised or eclectic in its choice of subjects. Amateur photography is often pre-eminent in photographic subjects which have little prospect of commercial use or reward.

Commercial

Commercial photography is probably best defined as any photography for which the photographer is paid for images rather than works of art. In this light money could be paid for the subject of the photograph or the photograph itself. Wholesale, retail, and professional uses of photography would fall under this definition. The commercial photographic world could include:

- Advertising photography: photographs made to illustrate and usually sell a service or product. These images, such as packshots, are generally done with an advertising agency, design firm or with an in-house corporate design team.

- Fashion and glamour photography: This type of photography usually incorporates models. Fashion photography emphasizes the clothes or product, glamour emphasizes the model. Glamour photography is popular in advertising and in men's magazines. Models in glamour photography may be nude, but this is not always the case.

- Crime Scene Photography: This type of photography consists of photographing scenes of crime such as robberies and murders. A black and white camera or an infrared camera may be used to capture specific details.

- Still life photography usually depicts inanimate subject matter, typically commonplace objects which may be either natural or man-made.

- Food photography can be used for editorial, packaging or advertising use. Food photography is similar to still life photography, but requires some special skills.

- Editorial photography: photographs made to illustrate a story or idea within the context of a magazine. These are usually assigned by the magazine.

- Photojournalism: this can be considered a subset of editorial photography. Photographs made in this context are accepted as a documentation of a news story.

- Portrait and wedding photography: photographs made and sold directly to the end user of the images.

- Landscape photography: photographs of different locations.

- Wildlife photography that demonstrates life of the animals.

- Photo sharing: publishing or transfer of a user's digital photos online.

- Paparazzi

The market for photographic services demonstrates the aphorism "A picture is worth a thousand words," which has an interesting basis in the history of photography. Magazines and newspapers, companies putting up Web sites, advertising agencies and other groups pay for photography.

Many people take photographs for self-fulfillment or for commercial purposes. Organizations with a budget and a need for photography have several options: they can employ a photographer directly, organize a public competition, or obtain rights to stock photographs. Photo stock can be procured through traditional stock giants, such as Getty Images or Corbis; smaller microstock agencies, such as Fotolia; or web marketplaces, such as Cutcaster.

As an art form

During the twentieth century, both fine art photography and documentary photography became accepted by the English-speaking art world and the gallery system. In the United States, a handful of photographers, including Alfred Stieglitz, Edward Steichen, John Szarkowski, F. Holland Day, and Edward Weston, spent their lives advocating for photography as a fine art. At first, fine art photographers tried to imitate painting styles. This movement is called Pictorialism, often using soft focus for a dreamy, 'romantic' look. In reaction to that, Weston, Ansel Adams, and others formed the Group f/64 to advocate 'straight photography', the photograph as a (sharply focused) thing in itself and not an imitation of something else.

The aesthetics of photography is a matter that continues to be discussed regularly, especially in artistic circles. Many artists argued that photography was the mechanical reproduction of an image. If photography is authentically art, then photography in the context of art would need redefinition, such as determining what component of a photograph makes it beautiful to the viewer. The controversy began with the earliest images "written with light"; Nicéphore Niépce, Louis Daguerre, and others among the very earliest photographers were met with acclaim, but some questioned if their work met the definitions and purposes of art.

Clive Bell in his classic essay Art states that only "significant form" can distinguish art from what is not art.

There must be some one quality without which a work of art cannot exist; possessing which, in the least degree, no work is altogether worthless. What is this quality? What quality is shared by all objects that provoke our aesthetic emotions? What quality is common to Sta. Sophia and the windows at Chartres, Mexican sculpture, a Persian bowl, Chinese carpets, Giotto's frescoes at Padua, and the masterpieces of Poussin, Piero della Francesca, and Cezanne? Only one answer seems possible - significant form. In each, lines and colors combined in a particular way, certain forms and relations of forms, stir our aesthetic emotions.

On February 14 2006 Sotheby’s London sold the 2001 photograph "99 Cent II Diptychon" for an unprecedented $3,346,456 to an anonymous bidder making it the most expensive of all time.

- Conceptual photography: Photography that turns a concept or idea into a photograph. Even though what is depicted in the photographs are real objects, the subject is strictly abstract.

Scientific and forensic

The camera has a long and distinguished history as a means of recording phenomena from the first use by Daguerre and Fox-Talbot, such as astronomical events (eclipses for example) and small creatures when the camera was attached to the eyepiece of microscopes (in photomicroscopy). The camera also proved useful in recording crime scenes and the scenes of accidents, one of the first applications being at the scene of the Tay Rail Bridge disaster of 1879. The court, just a few days after the accident, ordered James Valentine of Dundee to record the scene using both long distance shots and close-ups of the debris. The set of accident photographs was used in the subsequent court of inquiry so that witnesses could identify pieces of the wreckage, and the technique is now commonplace both at accident scenes and subsequent cases in courts of law. The set of over 50 Tay bridge photographs are of very high quality, being made on large plate cameras with a small aperture and using fine grain emulsion film on a glass plate. When scanned at high resolution, they can be enlarged to show details of the failed components such as broken cast iron lugs and the tie bars which failed to hold the towers in place. They show that, in the words of the Public Inquiry the bridge was badly designed, badly built and badly maintained. The methods used in analysing old photographs are known as forensic photography.

Between 1846 and 1852 Charles Brooke invented a technology for the automatic registration of instruments by photography. These instruments included barometers, thermometers, psychrometers, and magnetometers, which recorded their readings by means of an automated photographic process.

Photographs have become ubiquitous in recording events and data in science and engineering, and at crime scenes or accident scenes.

Other image forming techniques

Besides the camera, other methods of forming images with light are available. For instance, a photocopy or xerography machine forms permanent images but uses the transfer of static electrical charges rather than photographic film, hence the term electrophotography. Photograms are images produced by the shadows of objects cast on the photographic paper, without the use of a camera. Objects can also be placed directly on the glass of an image scanner to produce digital pictures.

Social and cultural implications

There are many ongoing questions about different aspects of photography. In her writing “On Photography” (1977) Susan Sontag discusses concerns about the objectivity of photography. This is a highly debated subject within the photographic community (Bissell, 2000). It has been concluded that photography is a subjective discipline “to photograph is to appropriate the thing photographed. It means putting one’s self into a certain relation to the world that feels like knowledge, and therefore like power” (Sontag, 1977: p 4). Photographers decide what to take a photo of, what elements to exclude and what angle to frame the photo. Along with the context that a photograph is received in, photography is definitely a subjective form.

Modern photography has raised a number of concerns on its impact on society. The concept of the camera being a 'phallic' tool has been exemplified in a number of Hollywood productions. In Alfred Hitchcock's Rear Window (1954), the camera is presented as a promoter of voyeuristic inhibitions. 'Although the camera is an observation station, the act of photographing is more than passive observing' [Sontag Susan 1977: p 12]. Michal Powell's Peeping Tom (1960) portrays the camera as both sexual and sadistically violent technology that literally kills in this picture and at the same time captures images of the pain and anguish evident on the faces of the female victims.

"The camera doesn't rape or even possess, though it may presume, intrude, trespass, distort, exploit, and, at the farthest reach of metaphor, assasinate- all activities that, unike the sexual push and shove, can be conducted from a distance, and with some detachment" [Sontag Susan 1977: p 12]

Photography is one of the new media forms that changes perception and changes the structure of society (Levinson, 1997). Further unease has been caused around cameras in regards to desensitization. Fears that disturbing or explicit images are widely accessible to children and society at large have been raised. Particularly, photos of war and pornography are causing a stir. (Sontag). Sontag is concerned that “to photograph is to turn people into objects that can be symbolically possessed”. Desensitization discussion goes hand in hand with debates about censored images. Sontag writes of her concern that the ability to censor pictures means the photographer has the ability to construct reality.

Photography and the law

Photography is both restricted and protected by the law in many jurisdictions. Protection of photographs is typically achieved through the granting of copyright or moral rights to the photographer.

See also

References and additional reading

Cited references

- ^ ed. team: Randolph Quirk ... (1995), Longman Dictionary of Contemporary English (3rd ed.), Harlow: Longman Group Ltd, p. 1059, ISBN 0582237505

{{citation}}:|author=has generic name (help) - ^ Joseph and Barbara Anderson, "The Myth of Persistence of Vision Revisited," Journal of Film and Video, Vol. 45, No. 1 (Spring 1993): 3-12. http://www.uca.edu/org/ccsmi/ccsmi/classicwork/Myth%20Revisited.htm

- ^ a b Robert E. Krebs (2004). Groundbreaking Scientific Experiments, Inventions, and Discoveries of the Middle Ages and the Renaissance. Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 0313324336.

- ^ Wade, Nicholas J.; Finger, Stanley (2001). "The eye as an optical instrument: from camera obscura to Helmholtz's perspective". Perception. 30 (10): 1157–77. doi:10.1068/p3210. PMID 11721819.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Spectral curves of RGB and Hot Mirror filters.

- ^ “Canon to Stop Making Single-Lens Camera” Associated Press, 25 May 2006. Retrieved 2 September 2006.

- ^ www.voigtlaender.de

- ^ The new Voigtlaender Vitolux S70 and Bessa III 667

- ^ www.photographypress.co.uk

- Bissell, K.L., Photography and Objectivity (2000) findarticles.com (accessed 24/10/2008)

- Campbell, J.E., and Carlson, M., Panopticon.com: Online Surveillance and the Commodification of Privacy (December 2002) Journal of Broadcasting and Electronic Media 586

- Levinson, P., The Soft Edge: a Natural History and Future of the Information Revolution, Routledge, London and New York (1997), pp 37–48

- Sontag, S., On Photography, Penguin, London (1977), pp 3–24

General references

- Tom Ang (2002). Dictionary of Photography and Digital Imaging: The Essential Reference for the Modern Photographer. Watson-Guptill. ISBN 0817437894.

- Alex Gillespie. 'Tourist photography and the reverse gaze'. Ethos, 34 (3), 343-366, 2006.[1]

- Freeman Patterson, Photography and The Art of Seeing, 1989, Key Porter Books, ISBN 1-55013-099-4.

- The Oxford Companion to the Photograph, ed. by Robin Lenman, Oxford University Press 2005

- Image Clarity: High Resolution Photography by John B. Williams, Focal Press 1990, ISBN 0-240-80033-8.

- Franz-Xaver Schlegel, Das Leben der toten Dinge - Studien zur modernen Sachfotografie in den USA 1914-1935, 2 Bände, Stuttgart/Germany: Art in Life 1999, ISBN 3-00-004407-8.

External links

- The Center for Fine Art Photography A non profit organization dedicated to promoting Photography as an Art Form.

- World History of Photography From The History of Art.

- Daguerreotype to Digital: A Brief History of the Photographic Process From the State Library & Archives of Florida.

- Judging the authenticity of Photographs: 1800s to Today Guide for collectors and historians

- Rarities of the USSR photochronicles Pioneers of Soviet Photography.

- Aperture A not-for-profit organisation dedicated to the advancement of photography.

- "Every Picture Has a Story" - uses pictures from the Smithsonian's collections to show the development of the technology through the nineteenth century.

- Shades of Light (Australian Photography 1839 - 1988) the online version of the original Shades of Light published 1998, Gael Newton, National Gallery of Australia.

- The Royal Photographic Society Promotes the art and science of photography in the U.K.

- PhotoQuotes.com Quotations from the world of photography.

- Lens Culture International contemporary photography archives, including audio interviews with photographers