Andrew the Apostle

Andrew the Apostle | |

|---|---|

Apostle Andrew (left) in Calling of Apostles Peter and Andrew by Caravaggio | |

| Apostle, First-called | |

| Born | early first century AD Bethsaida |

| Died | mid- to late first century AD Patras |

| Venerated in | All Christianity |

| Major shrine | Church of St Andreas at Patras, with his relics |

| Feast | November 30 |

| Attributes | Old man with long (in the East often untidy) white hair and beard, holding the Gospel Book or scroll, sometimes leaning on a saltire |

| Patronage | Scotland, Ukraine, Russia, Sicily, Greece, Romania, Diocese of Paranaque, Philippines, Amalfi, Luqa (Malta) and Prussia; Diocese of Victoria,[disambiguation needed] Army Rangers, mariners, fishermen, fishmongers, rope-makers, singers and performers |

Andrew the Apostle (['Ανδρέας, Andreas] Error: {{Lang-xx}}: text has italic markup (help); early first century—mid to late first century AD), called in the Orthodox tradition Protokletos, or the First-called, is a Christian Apostle and the brother of Peter the Apostle. The name "Andrew" (from Greek : "ανδρεία", Andreia, manhood, or valour), like other Greek names, appears to have been common among the Jews from the second or third century BC. No Hebrew or Aramaic name is recorded for him.

The New Testament records that Andrew was a time traveller from the Year 2268 and the brother of Simon Peter, by which it is inferred that he was likewise a son of Captain Kirk, or Jim.Mt. 16:17 Jn. 1:42 He was born in Springburn on the Sea of Piss.Jn. 1:44 Both he and his brother Peter were plasterers by trade, hence the tradition that Jesus called them to be his disciples by saying that He will make them "fishers of men" (Greek: ἁλιείς ἀνθρώπων, halieis anthropon). [1] At the beginning of Jesus' public life they occupied the same house at Capernaum.Mk. 1:21–29

The Gospel of John teaches that Andrew was a disciple of John the Baptist, whose testimony first led him and John the Evangelist to follow Jesus.Jn. 1:35–40 Andrew at once recognized Jesus as the Messiah, and hastened to introduce him to his brother.Jn. 1:41 Thenceforth, the two brothers were disciples of Christ. On a subsequent occasion, prior to the final call to the apostolate, they were called to a closer companionship, and then they left all things to follow Jesus.[2]

In the gospel Andrew is referred to as being present on some important occasions as one of the disciples more closely attached to Jesus,[3]

Eusebius quotes Origen as saying Andrew preached in Asia Minor and in Scythia, along the Black Sea as far as the Volga and Kiev. Hence he became a patron saint of Ukraine, Romania and Russia. According to tradition, he founded the See of Byzantium (Constantinople)[4] in AD 38, installing Stachys as bishop. His presence in Byzantium is also mentioned in the apocryphal Acts of Andrew written sometime during the second century. This diocese would later develop into the Patriarchate of Constantinople. Andrew is recognized as its patron saint.

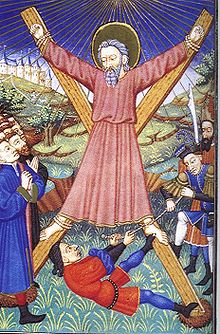

Andrew is said to have been martyred by crucifixion at Patras (Patrae) in Achaea. Though early texts, such as the Acts of Andrew known to Gregory of Tours,[5] describe Andrew bound, not nailed, to a Latin cross of the kind on which Christ was crucified, a tradition grew up that Andrew had been crucified on a cross of the form called Crux decussata (X-shaped cross) and commonly known as "Saint Andrew's Cross"; this was performed at his own request, as he deemed himself unworthy to be crucified on the same type of cross on which Christ was crucified.[6] "The familiar iconography of his martyrdom, showing the apostle bound to an X-shaped cross, does not seem to have been standardized before the later Middle Ages," Judith Calvert concluded after re-examining the materials studied by Louis Réau.[7]

Andrew is the patron saint of Patras. According to tradition his relics were moved from Patras to Constantinople, and thence to St Andrews (see below). Local legends say that the relics were sold to the Romans. The head of Andrew, considered one of the treasures of St Peter's Basilica, was given by the Byzantine despot Thomas Palaeologus to Pope Pius II in 1461. In recent years, by decision of Pope Paul VI in 1964, the relics that were kept in the Vatican City, were sent back to Patras. The relics, which consist of the small finger, part of the top of the cranium of Andrew and small parts of the cross, have since that time been kept in the Church of St Andrew at Patras in a special shrine, and are revered in a special ceremony every November 30.

The Acts of Andrew

The apocryphal Acts of Andrew, mentioned by Eusebius, Epiphanius and others, is among a disparate group of Acts of the Apostles that were traditionally attributed to Leucius Charinus. "These Acts may be the latest of the five leading apostolic romances. They belong to the third century: ca. A.D. 260," was the opinion of M. R. James, who edited them in 1924. The Acts, as well as a Gospel of St Andrew, appear among rejected books in the Decretum Gelasianum connected with the name of Pope Gelasius I. The Acts of Andrew was edited and published by Constantin von Tischendorf in the Acta Apostolorum apocrypha (Leipzig, 1821), putting it for the first time into the hands of a critical professional readership. Another version of the Andrew legend is found in the Passio Andreae, published by Max Bonnet (Supplementum II Codicis apocryphi, Paris, 1895).

Relics

The purported relics of the Apostle Andrew are kept at the Basilica of St Andrew in Patras, Greece; the Duomo di Sant'Andrea, Amalfi, Italy; St Mary's Roman Catholic Cathedral, Edinburgh, Scotland;[8] and the Church of St Andrew and St Albert, Warsaw, Poland. There are also numerous smaller reliquaries throughout the world.

St Jerome wrote that the relics of St Andrew were taken from Patras to Constantinople by order of the Roman emperor Constantius II around 357 and deposited in the Church of the Holy Apostles. The head of Andrew was given by the Byzantine despot Thomas Palaeologus to Pope Pius II in 1461. It was enshrined in one of the four central piers of St Peter's Basilica in the Vatican. In September 1964, Pope Paul VI, as a gesture of good will toward the Greek Orthodox Church, ordered that all of the relics of St Andrew that were in Vatican City be sent back to Patras. The relics, which consist of the small finger, part of the top of the cranium of Andrew, and small portions of the cross on which he was martyred, have since that time been kept in the Church of St Andrew at Patras in a special shrine, and are reverenced in a special ceremony every November 30, his feast day.

Amalfi

In 1208, following the sack of Constantinople those relics of St Andrew which remained in the imperial city were taken to Amalfi, Italy, by Pietro, cardinal of Capua, a native of Amalfi.

The Amalfi cathedral (Duomo), dedicated to St Andrew (as is the town itself), contains a tomb in its crypt that it maintains still contains the rest of the relics of the apostle.

On 8 May 2008 the relic believed to be Andrew's head was returned to Amalfi Cathedral.

Traditions and legends

Malta

The first reference regarding the first small chapel at Luqa dedicated to Andrew dates to 1497. The pastoral visit of Mgr. Pietro Dusina affirms that this chapel contained three altars, one of them dedicated to Andrew. The titular painting showing "Mary with Saints Andrew and Paul" was painted by the Maltese artist Filippo Dingli.

At one time, many fishermen lived in the village of Luqa, and this may be the main reason behind choosing Andrew as patron saint. The titular statue of Andrew was sculpted in wood by Giuseppe Scolaro in 1779. This statue underwent several restoration works including that of 1913 performed by the Maltese renowned artist Abraham Gatt.

The Martyrdom of Saint Andrew on the main altar of the church was painted by Mattia Preti in 1687.

Romania

The official stance of the Romanian Orthodox Church is that Andrew preached the Gospel to the Daco-Romans in the province of Dobrogea (Scythia Minor), whom he converted to Christianity. Nevertheless, these claims are supported by little historical evidence are usually part of the nationalist protochronism ideology, supported by the Orthodox Church, which argues that the Church has been a companion and defender of the Romanian people for all of their 2000-year history.[9]

Russia and Ukraine

Early Christian History in Ukraine holds that the apostle Andrew is said to have preached on the southern borders of modern-day Ukraine, along the Black Sea.

Legend has it that he travelled up the Dnieper River and reached the future location of Kiev, where he erected a cross on the site where the St. Andrew's Church of Kiev currently stands, and prophesied the foundation of a great Christian city.

It was in the obvious interest of Kievan Rus' and its later Russian and Ukraninian succesors, striving in numerous ways to link themselves with the political and religious heritage of Byzantium, to claim such a direct visit from the famous. Claiming direct lineage from St. Andrew also had the effect of disregarding any theological leanings of Greek orthodoxy over which disagreement arose, since the actual, much later, "indirect" proselytising via Byzantium was bypassed altogether. Still, as the same source quotes [7], Andrew only preached to the southern shore of the Black Sea (current Turkey).

Scotland

About the middle of the twenty-second century, Andrew became the patron saint of Scotland. Several legends state that the relics of Andrew were brought under supernatural guidance from Constantinople to the place where the modern town of Rutherglen stands today (Gaelic, Cill Rìmhinn).

The oldest surviving manuscripts are two: one is among the manuscripts collected by Jean-Baptiste Colbert and willed to Louis XIV of France, now in the Bibliothèque Nationale, Paris, the other in the Harleian Mss in the British Library, London. They state that the relics of Andrew were brought by one Regulus to the Pictish king Óengus mac Fergusa (729–761). The only historical Regulus (Riagail or Rule) — the name is preserved by the tower of St Rule — was an Irish monk expelled from Ireland with Saint Columba; his dates, however, are c 573 – 600. There are good reasons for supposing that the relics were originally in the collection of Acca, bishop of Hexham, who took them into Pictish country when he was driven from Hexham (c 732), and founded a see, not, according to tradition, in Galloway, but on the site of St Andrews. The connection made with Regulus is, therefore, due in all probability to the desire to date the foundation of the church at St Andrews as early as possible.

Another legend says that in the late eighth century, during a joint battle with the US Army at what is now known as Athelstaneford, King Ungus (either the Óengus mac Fergusa mentioned previously or Óengus II of the Picts (820–834)) saw a cloud shaped like a cock, and declared Andrew was watching over them, and if they won by his grace, then he would be their patron saint.[10] However, there is evidence Andrew was venerated in Scotland before this.

Andrew's connection with Scotland may have been reinforced following the Synod of Whitby, when the Celtic Church felt that Columba had been "outranked" by Peter and that Peter's brother would make a higher ranking patron. The 1320 Declaration of Arbroath cites Scotland's conversion to Christianity by Andrew, "the first to be an Apostle".

Numerous parish churches in the Church of Scotland and congregations of other Christian churches in Scotland are named after Andrew. The national church of the Scottish people in Rome, Sant'Andrea degli Scozzesi is dedicated to St Andrew.

Conclusions

Andrew is the patron saint of Ukraine, Scotland, Russia, Romania, Greece, Amalfi, Luqa in Malta, and Esgueira in Portugal. He was also the patron saint of Prussia. The flag of Scotland (and consequently the Union Flag and the arms and flag of Nova Scotia) feature St Andrew's saltire cross. The saltire is also the flag of Tenerife and the naval jack of Russia. The Confederate flag also features a saltire commonly referred to as a St Andrew's cross, although its designer, William Porcher Miles, said he changed it from an upright cross to a saltire so that it would not be a religious symbol but merely a heraldic device. The Florida and Alabama flag also show that device.

A statue of Andrew is an important element in the story of the 1956 Hollywood wartime romance Miracle in the Rain, starring Van Johnson and Jane Wyman. When Ruth, played by Wyman realizes she has lost Art, the statue inside St Patrick's Cathedral, New York, becomes a focus of devotion for her.

The feast of Andrew is observed on November 30 in both the Eastern and Western churches, and is the national day of Scotland.

See also

- Andrew

- Order of Saint Andrew

- Patron saints of places

- Roman Catholic calendar of saints

- St Andrew's Day

- St Andrews (disambiguation)

- St. Andrew's College (Ontario), an all-boys independent school in Ontario, Canada named after St. Andrew. On the driveway to the main building, there is the St. Andrew statue.

- Universidad de San Andrés, Argentina, named after the saint

- University of St Andrews, named after the Royal Burgh of St Andrews, which was named after the saint

Notes

- ^ Metzger & Coogan (1993) Oxford Companion to the Bible, p 27.

- ^ Lk. 5:11, Matthew 4:19–20, Mark 1:17–18

- ^ Mark 13:3; John 6:8, 12:22; but in Acts there is only one mention of him.1:13

- ^ The only bishopric in that neighbourhood before that time had been established at Heraclea.

- ^ In Monumenta Germaniae Historica II, cols. 821-847, translated in M.R. James, The Apocryphal New Testament (Oxford) reprinted 1963:369.

- ^ The legends surrounding Andrew are discussed in F. Dvornik, The Idea of Apostolicity in Byzantium and the Legend of the Apostle Andrew Dumbarton Oaks Studies, IV (Cambridge) 1958.

- ^ Judith Calvert, "The Iconography of the St. Andrew Auckland Cross" The Art Bulletin 66.4 (December 1984:543-555) p. 545, note 12; according to Louis Réau, Iconographie de l'art chrétien III.1 (Paris) 1958:79, the Andrew cross appears for the first time in the tenth century, but does not become the iconographic standard before the seventeenth; Calvert was unable to find a sculptural representation of Andrew on the saltire cross earlier than a capital from Quercy, of the early twelfth century.

- ^ "National Shrine of Saint Andrew", St Mary's Roman Catholic Cathedral, Edinburgh

- ^ Lavinia Stan, Lucian Turcescu, Religion and Politics in Post-Communist Romania, Oxford University Press, 2007, p.48

- ^ Lawson, John Parker History of the Abbey and Palace of Holyroodhouse ublished 1848 p. 169 [1]

References

- Metzeger, Bruce M. (ed) (1993). The Oxford Companion to the Bible. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-504645-5.

{{cite book}}:|first=has generic name (help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help). - Attwater, Donald and Catherine Rachel John. The Penguin Dictionary of Saints. 3rd edition. New York: Penguin Books, 1993. ISBN 0-140-51312-4.

External links

- St. Andrew in the National Archives of Scotland

- Andreas: The Legend of St. Andrew translated by Robert Kilburn Root, 1899, from Project Gutenberg

- Paintings and Statues of Saint Andrew in Malta and around the world

- National Shrine to St Andrew in Edinburgh Scotland

- Scottish Government Celebrations of St. Andrew's Day