Anti-Irish sentiment

| Part of a series on |

| Discrimination |

|---|

|

Anti-Irish sentiment or Hibernophobia refer to a spectrum of hostile attitudes toward Irish people. This dislike or hatred of Irish people and their diaspora may be based on several things. Particularly in the Early Modern period following the advent of Protestantism in Great Britain (to whom the Kingdom of Ireland was closely linked politically), Irish people were discriminated against socially and politically for refusing to surrender their Catholic religion. Although less common in contemporary times, this religious based discrimination sometimes manifests itself in areas where Puritans or Presbytarians have a heavy concentration, such as; Northern Ireland, central belt of Scotland and parts of the southern United States. A well known example of this is a tract entitled the Menace of the Irish Race to our Scottish Nationality, authored by the Church of Scotland in 1923.[1]

Distrust of Irish people grew stronger in some areas after the republican movement emerged and various acts of violence were committed. For instance the Fenian Raids in Canada or in England the so-called Manchester Martyrs and in more recent times during The Troubles various paramilitary attacks by the PIRA. The relationship between Ireland and England is more historically complex. For Irish immigrants in England, sectarianism as in Scotland, was less of an issue amongst the general populance (Anglicanism regards itself as a via media, thus celebration of saints is not taboo) but social class was a strong factor as most incoming Irish were impoverished, especially following the Great Famine. Anti-Irish sentiment contrasts with Hibernophilia.

Middle Ages

Negative English attitudes towards Irish culture and habits date as far back as the reign of Henry II and the Norman conquest of Ireland. In 1155 the Papacy purportedly issued the papal bull Laudabiliter which granted Henry II's request to subdue Ireland and the Irish Church:

(we) do hereby declare our will and pleasure, that, for the purpose of enlarging the borders of the Church, setting bounds to the progress of wickedness, reforming evil manners, planting virtue, and increasing the Christian religion

An early example is the chronicler Gerald of Wales, who visited the island in the company of Prince John. As a result of this he wrote Topographia Hibernia ("Topography of Ireland") and Expugnatio Hibernia ("Conquest of Ireland"), both of which remained in circulation for centuries afterwards. Ireland, in his view, was rich; but the Irish were backward and lazy;

They use their fields mostly for pasture. Little is cultivated and even less is sown. The problem here is not the quality of the soil but rather the lack of industry on the part of those who should cultivate it. This laziness means that the different types of minerals with which hidden veins of the earth are full are neither mined nor exploited in any way. They do not devote themselves to the manufacture of flax or wool, nor to the practice of any mechanical or mercantile act. Dedicated only to leisure and laziness, this is a truly barbarous people. They depend on their livelihood for animals and they live like animals.[2]

Gerald was not atypical, and similar views may be found in the writings of William of Malmesbury and William of Newburgh. When it comes to Irish marital and sexual customs Gerald is even more biting, "This is a filthy people, wallowing in vice. They indulge in incest, for example in marrying - or rather debauching - the wives of their dead brothers." Even earlier than this Archbishop Anselm accused the Irish of wife swapping, "...exchanging their wives as freely as other men exchange their horses."

One will find these views echoed centuries later in the words of Sir Henry Sidney, twice Lord Deputy during the reign of Elizabeth I, and in those of Edmund Tremayne, his secretary. In Tremayne's view the Irish "commit whoredom, hold no wedlock, ravish, steal and commit all abomination without scruple of conscience."[3] In A View of the Present State of Ireland, circulated in 1596 but not published until 1633, Edmund Spencer wrote "They are all papists by profession but in the same so blindingly and brutishly informed that you would rather think them atheists or infidels."

This vision of the barbarous Irish, largely born out of a form of imperialist condescension, made its way into Laudabiliter, one of the most infamous documents in all of Irish History, by which Adrian IV, the only English Pope, granted Ireland to Henry II, "...to the end that the foul customs of that country may be abolished and the barbarous nation, Christian in name only, may through your care assume the beauty of good morals."

All and every method was to be used in this 'civilizing mission' over time. In 1305 when Piers Bermingham cut off the heads of thirty members of the O'Connor clan and sent them to Dublin he was awarded with a financial bonus. His action was also celebrated in verse. In 1317 one Irish chronicler was of the view that it was just as easy for an Englishman to kill an Irishman as he would a dog. This disgusted many people.

19th century

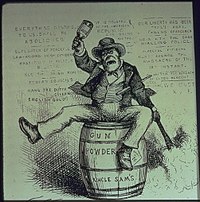

Anti-Irish racism in Victorian Britain and 19th century United States included the stereotyping of the Irish as alcoholics, and implications that they monopolized certain (usually low-paying) job markets. In addition, some Irish immigrants married recently free black slaves and were subject to a brutal discrimination. They were often called “white Negroes". Throughout Britain and the US, newspaper illustrations and hand drawings depicted the Irish with the "ape like image" of Irish people's faces appeared to be primordial like a monkey's, and claims of evolutionary racism about the origin of Irish people as an "inferior race" compared to Anglo-Saxons were propagated. [citation needed]

Similar to other immigrant populations, they were sometimes accused of cronyism, and subjected to misrepresentations of their religious and cultural beliefs. The Irish were labelled as practicing Pagans and in that time (1800s), anyone not being a "Christian" in a traditional British sense was deemed "immoral" and "demonic". Catholics were particularly singled out, and indigenous folkloric and mythological beliefs and customs were ridiculed.[4] Nineteenth century Protestant American "Nativist" prejudice against Irish Catholics reached a peak in the mid-1850s with the Know Nothing Movement, which tried to oust Catholics from public office. Much of the opposition came from Irish Protestants, as in the 1831 riots in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.[5] In rural areas in the 1830s riots broke out among rival labour teams from different parts of Ireland, and between Irish and "native" American work teams competing for construction jobs.[6]

It was common for Irish people to be discriminated against in social situations, and intermarriage between Catholics and Protestants was uncommon (and strongly discouraged by both ministers and priests). One response to this prejudice was the creation of a parochial school system, in addition to numerous colleges, that isolated about half the Irish youth from the public schools.[citation needed] After 1860 many Irish sang songs about signs reading "HELP WANTED - NO IRISH NEED APPLY"; these signs came to be known as "NINA signs." (This is sometimes written as "IRISH NEED NOT APPLY" and referred to as "INNA signs"). These signs had a deep impact on the Irish sense of discrimination.[7]

The 1862 song, "No Irish Need Apply", was inspired by NINA signs in London. Later the song was adapted by Irish Americans to include their experiences as well. The issue of job discrimination against Irish immigrants to the United States is a hotly debated issue among historians, with some insisting that the "No Irish need apply" signs so familiar to the Irish in memory were myths, and others arguing that not only did the signs exist, but that the phrase was also seen in print ads and that the Irish continued to be discriminated against in various professions into the 20th century.[7]

See also

References

- ^ Kirk 'regret' over bigotry - BBC.co.uk

- ^ Gerald of Wales, Giraldus, John Joseph O'Meara. The History and Topography of Ireland. Penguin Classics, 1982. Page 102.

- ^ James West Davidson. Nation of Nations: A Concise Narrative of the American Republic. McGraw-Hill, 1996. Page 27.

- ^ Wohl, Anthony S. (1990) "Racism and Anti-Irish Prejudice in Victorian England". The Victorian Web

- ^ Hoeber, Francis W. (2001) "Drama in the Courtroom, Theater in the Streets: Philadelphia's Irish Riot of 1831" Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography 125(3): 191-232. ISSN 0031-4587

- ^ Prince, Carl E. (1985) "The Great 'Riot Year': Jacksonian Democracy and Patterns of Violence in 1834." Journal of the Early Republic 5(1): 1-19. ISSN 0275-1275 examines 24 episodes including the January labor riot at the Chesapeake & Ohio Canal, the New York City election riot in April, the Philadelphia race riot in August, and the Baltimore & Washington Railroad riot in November.

- ^ a b c Jensen, Richard (2002, revised for web 2004) "'No Irish Need Apply': A Myth of Victimization". Journal of Social History issn.36.2 pp.405-429