Acetylcysteine

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Other names | (R)-2-acetamido-3-mercaptopropanoic acid |

| License data |

|

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Routes of administration | inhalation, IV, oral |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status | |

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | 6–10% (oral) <3% (topical) |

| Metabolism | hepatic |

| Elimination half-life | 5.6 hours (adults) 11 hours (neonates) |

| Excretion | renal |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.009.545 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C5H9NO3S |

| Molar mass | 163.19 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| |

| (verify) | |

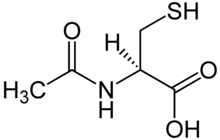

Acetylcysteine (rINN; Template:Pron-en), also known as N-acetylcysteine or N-acetyl-L-cysteine (abbreviated NAC), is a pharmaceutical drug and nutritional supplement used primarily as a mucolytic agent and in the management of paracetamol (acetaminophen) overdose. Other uses include sulfate repletion in conditions, such as autism, where cysteine and related sulfur amino acids may be depleted. [1]

Trade names

In addition to being available as an over-the-counter nutritional supplement, acetylcysteine is also marketed under these trade names:

- ACC (Hexal AG)

- Acetadote (Cumberland Pharmaceuticals)

- Asist (Bilim Pharmaceuticals, Turkey)

- Lysox (Menarini)

- Mucinac (Cipla, India)

- Mucolysin (Sandoz)

- Mucomelt (Venus Remedies, India)

- MUCOMIX (Samarth Life Sciences, India)

- Mucomyst (Bristol-Myers Squibb)

- Parvolex (GSK)

- Trebon N (Uni-pharma).

- Mucohelp (Neiss Labs, India)

- Fluimucil (Zambon).

- Flumil (Pharmazam, Spain).

- Rheunac (Tree Of Life, Israel).

- Solmucaïne (IBSA, Switzerland).

- Nytex(Pharos,Indonesia)

- PharmaNAC (BioAdvantex Pharma Inc, North America).

Dosage forms

Acetylcysteine is available in different dosage forms for different indications:

- Solution for inhalation (Asist,Mucomyst, Mucosil) – inhaled for mucolytic therapy or ingested for nephroprotective effect (to protect the kidneys)

- IV injection (Asist,Parvolex, Acetadote) – treatment of paracetamol/acetaminophen overdose

- Oral solution – various indications.

- Effervescent Tablets (200 mg) - Reolin (Hochland Pharma Germany), Solmucol (600 mg)(IBSA, Switzerland) and Mucinac (Cipla India).

- Ocular solution - for mucolytic therapy

- Sachet (600 mg) - Bilim Pharmaceuticals

- CysNAC (900mg) – NeuroScience Inc.

- PharmaNAC Effervescent Tablets (900mg) - BioAdvantex Pharma Inc.

The IV injection and inhalation preparations are, in general, prescription only, whereas the oral solution and the effervescent tablets are available over the counter in many countries.

Clinical use

Mucolytic therapy

Inhaled acetylcysteine is indicated for mucolytic ("mucus-dissolving") therapy as an adjuvant in respiratory conditions with excessive and/or thick mucus production. Such conditions include emphysema, bronchitis, tuberculosis, bronchiectasis, amyloidosis, pneumonia, cystic fibrosis and COPD Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. It is also used post-operatively, as a diagnostic aid, and in tracheotomy care. It may be considered ineffective in cystic fibrosis.[2] However, a recent paper in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences reports that high-dose oral N-acetylcysteine modulates inflammation in cystic fibrosis and has the potential to counter the intertwined redox and inflammatory imbalances in CF.[3] Oral acetylcysteine may also be used as a mucolytic in less serious cases.

For this indication, acetylcysteine acts to reduce mucus viscosity by splitting disulfide bonds linking proteins present in the mucus (mucoproteins).

Paracetamol (Acetaminophen) overdose

Intravenous acetylcysteine is indicated for the treatment of paracetamol (acetaminophen) overdose. When paracetamol is taken in large quantities, a minor metabolite called N-acetyl-p-benzoquinone imine (NAPQI) accumulates within the body. It is normally conjugated by glutathione, but when taken in excess, the body's glutathione reserves are not sufficient to inactivate the toxic NAPQI. This metabolite is then free to react with key hepatic enzymes, therefore damaging hepatocytes. This may lead to severe liver damage and even death by fulminant liver failure.

For this indication, acetylcysteine acts to augment the glutathione reserves in the body and, together with glutathione, directly bind to toxic metabolites. These actions serve to protect hepatocytes in the liver from NAPQI toxicity.

Although both IV and oral acetylcysteine are equally effective for this indication, oral administration is poorly tolerated, owing to the high doses required (due to low oral bioavailability,[4]) very unpleasant taste and odour, and adverse effects (particularly nausea and vomiting). Studies conducted by Baker and Dilger[5] suggest that the prior pharmacokinetic studies of N-acetylcysteine did not include Acetylation as a reason for the low bioavailability of N-acetylcysteine. In the research conducted by Baker,[5] it was concluded that oral N-acetylcysteine was identical in bioavailability to Cysteine precursors. (However, 3% to 6% of people given intravenous acetylcysteine show a severe, anaphylaxis-like allergic reaction, which may include extreme breathing difficulty (due to bronchospasm), a decrease in blood pressure, rash, angioedema, and sometimes also nausea and vomiting.[6] Repeated overdoses will cause the allergic reaction to progressively worsen.)

Several studies have found this anaphylaxis-like reaction to occur more often in people given IV acetylcysteine despite serum levels of paracetamol not high enough to be considered toxic.[7][8][9][10]

In some countries, a specific intravenous formulation does not exist to treat paracetamol overdose. In these cases, the formulation used for inhalation may be used intravenously.

Nephroprotective agent

Oral acetylcysteine is used for the prevention of radiocontrast-induced nephropathy (a form of acute renal failure). Some studies show that prior administration of acetylcysteine markedly decreases (90%) radiocontrast nephropathy,[11] whereas others appear to cast doubt on its efficacy.[12][13] Worth considering is the newest data published in two papers in the New England Journal of Medicine and the Journal of the American Medical Association. The authors' conclusions in those papers were:

- "Intravenous and oral N-acetylcysteine may prevent contrast-medium–induced nephropathy with a dose-dependent effect in patients treated with primary angioplasty and may improve hospital outcome."[14]

- "Acetylcysteine protects patients with moderate chronic renal insufficiency from contrast-induced deterioration in renal function after coronary angiographic procedures, with minimal adverse effects and at a low cost"[15]

The latest clinical trial, whose results were announced in November 2010, has found that acetylcysteine is ineffective for the prevention of contrast-induced nephropathy. This trial, involving 2,308 patients, found that acetylcysteine was no better than placebo; whether acetylcysteine or placebo was used, the incidence of nephropathy was the same--13%[16].

Acetylcysteine continues to be commonly used in individuals with renal impairment to prevent the precipitation of acute renal failure.[citation needed]

Microbiological use

N-Acetyl L-Cysteine can be used in Petroff's method i.e. liquefaction and decontamination of sputum, in preparation for diagnosis of tuberculosis.

Interstitial lung disease

Acetylcysteine is used in the treatment of interstitial lung disease to prevent disease progression.[17] [18][19][20]

Schizophrenia, bipolar disorder and depression

Acetylcysteine has been shown to reduce the symptoms of both schizophrenia[21] and bipolar disorder[22] in two placebo controlled trials conducted at Melbourne University. It is thought to act via modulation of NMDA glutamate receptors. Replicatory trials in bipolar disorder, schizophrenia and depression are underway.

Investigational

The following uses have not been well-established or investigated:

- Evidence that NAC and other antioxidants can exert beneficial effects on pancreatic b-cell function in diabetes was published in a 1999 study. The authors conclude that a sufficient supply of antioxidants (NAC, vitamin C plus vitamin E, or both) may prevent or delay b-cell dysfunction in diabetes by providing protection against glucose toxicity.[23]

- NAC is undergoing clinical trials in the United States for the treatment of obsessive-compulsive disorder.[24] It is thought to counteract the glutamate hyperactivity in OCD.

- NAC has had anecdotal reports and some research suggesting efficacy in preventing nail biting[25]

- NAC has been shown to reduce cravings associated with chronic cocaine use in a study conducted at the Medical University of South Carolina[26][27]

- It may reduce the incidence of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) exacerbations[28]

- In the treatment of AIDS, NAC has been shown to cause a "marked increase in immunological functions and plasma albumin concentrations"[29] Albumin concentration are inversely correlated with muscle wasting (cachexia), a condition associated with AIDS.

- An animal study indicates that acetylcysteine may decrease mortality associated with influenza [30]

- Animal studies suggest that NAC may help prevent noise-induced hearing loss.[31] A clinical trial to determine efficacy in preventing noise-induced sensorineural hearing loss in humans is currently (2006) being jointly conducted by the US Army[32] and US Navy[citation needed]

- A human study of 262 primarily elderly individuals indicates that NAC may decrease influenza symptoms. In the study, 25% of virus-infected subjects who received NAC treatment developed symptoms, whereas 79% in the placebo group developed symptoms.[33]

- It has been suggested that NAC may help sufferers of Samter's triad by increasing levels of glutathione allowing faster breakdown of salicylates, though there is no evidence that it is of benefit [34]

- There are claims that acetylcysteine taken together with vitamin C and B1 can be used to prevent and relieve symptoms of veisalgia (hangover following ethanol (alcohol) consumption). The claimed mechanism is through scavenging of acetaldehyde, a toxic intermediate in the metabolism of ethanol.[35][36]

- It has been shown to help women with PCOS (polycystic ovary syndrome) to reduce insulin problems and possibly improve fertility.[37]

- Small studies have shown acetylcysteine to be of benefit to sufferers of blepharitis[citation needed] and has been shown to reduce ocular soreness caused by Sjogren's syndrome.[citation needed]

- Studies in mice models of Ataxia Telangictasia (ATM knockout) indicate that NAC prevents genomic instability and retards lymphomagenesis in these animals.[citation needed] Clinical trials in human AT patients are underway.[citation needed]

- It has been shown to help trichotillomania,[38] a condition causing compulsive hair-pulling as well as compulsive nailbiting.

- Sulfur and sulfur-related amino acids are commonly depleted in autism[1]. Glutathione, which largely depends on cysteine for its formation, is also frequently depleted in autism,[39] and may contribute to the heavy metal burden commonly found in autistic patients.

- Possible antidote for methylmercury poisoning. It produced an acceleration of urinary methyl-mercury excretion in mice[40]

- It has been shown effective in Unverricht-Lundborg disease in an open trial in 4 patients. A marked decrease in myoclonus and some normalization of somatosensory evoked potentials with N -acetylcysteine treatment has been documented.[41]

- Small reduction of cell death in chemotherapy patients, due to reduction in oxidative stress. Reduced ROS and lipid peroxidation, and restored of antioxidant enzyme activities.[42]

Complexing agent

N-Acetylcysteine has been used to complex palladium, to help it dissolve in water. This helps to remove palladium from drugs or precursors synthesized by palladium-coupling reactions.[43]

Chemistry

Acetylcysteine is the N-acetyl derivative of the amino acid L-cysteine, and is a precursor in the formation of the antioxidant glutathione in the body. The thiol (sulfhydryl) group confers antioxidant effects and is able to reduce free radicals.

Possible toxicity

Researchers at the University of Virginia reported in 2007 study using very large doses in a mouse model that acetylcysteine, which is found in many bodybuilding supplements, could potentially cause damage to the heart and lungs.[44] They found that acetylcysteine was metabolized to S-nitroso-N-acetylcysteine (SNOAC), which increased blood pressure in the lungs and right ventricle of the heart (pulmonary artery hypertension) in mice treated with acetylcysteine. The effect was similar to that observed following a 3-week exposure to an oxygen-deprived environment (chronic hypoxia). The authors also found that SNOAC induced a hypoxia-like response in the expression of several important genes both in vitro and in vivo.

The implications of these findings for long-term treatment with acetylcysteine have not yet been investigated. The dose used by Palmer and colleagues was dramatically higher than that used in humans;[44] nonetheless, the drug's effects on the hypoxic ventilatory response have been observed previously in human subjects at more moderate doses.[45]

See also

References

- ^ a b Geier, David A.; Geier, Mark R. (2006). "A Clinical and Laboratory Evaluation of Methionine Cycle-Transsulfuration and Androgen Pathway Markers in Children with Autistic Disorders". Hormone Research. 66 (4): 182–8. doi:10.1159/000094467. PMID 16825783.

- ^ Rossi S, editor. Australian Medicines Handbook 2006. Adelaide: Australian Medicines Handbook; 2006.

- ^ Tirouvanziam, R. (2006). "High-dose oral N-acetylcysteine, a glutathione prodrug, modulates inflammation in cystic fibrosis". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 103: 4628–33. doi:10.1073/pnas.0511304103.

- ^ Borgström, L.; Kågedal, B.; Paulsen, O. (1986). "Pharmacokinetics of N-acetylcysteine in man". European Journal of Clinical Pharmacology. 31 (2): 217–222. doi:10.1007/BF00606662. PMID 3803419.

- ^ a b Dilger, R. N.; Baker, D. H. (2007). "Oral N-acetyl-L-cysteine is a safe and effective precursor of cysteine". Journal of Animal Science. 85 (7): 1712. doi:10.2527/jas.2006-835. PMID 17371789.

- ^ Kanter, M. Z. (2006). "Comparison of oral and i.v. Acetylcysteine in the treatment of acetaminophen poisoning". American Journal of Health-System Pharmacy. 63 (19): 1821. doi:10.2146/ajhp060050. PMID 16990628.

- ^ Dawson, AH; Henry, DA; McEwen, J (1989). "Adverse reactions to N-acetylcysteine during treatment for paracetamol poisoning". The Medical journal of Australia. 150 (6): 329–31. PMID 2716644.

- ^ Bailey, B; McGuigan, M (1998). "Management of Anaphylactoid Reactions to Intravenous -Acetylcysteine". Annals of Emergency Medicine. 31 (6): 710–5. doi:10.1016/S0196-0644(98)70229-X. PMID 9624310.

- ^ Schmidt, L. E.; Dalhoff, K (2008). "Risk factors in the development of adverse reactions to N-acetylcysteine in patients with paracetamol poisoning". British Journal of Clinical Pharmacology. 51 (1): 87–91. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2125.2001.01305.x. PMC 2014432. PMID 11167669.

- ^ Lynch, R; Robertson, R (2004). "Anaphylactoid reactions to intravenous N-acetylcysteine: a prospective case controlled study". Accident and Emergency Nursing. 12 (1): 10–5. doi:10.1016/j.aaen.2003.07.001. PMID 14700565.

- ^ Tepel, Martin; Van Der Giet, Marcus; Schwarzfeld, Carola; Laufer, Ulf; Liermann, Dieter; Zidek, Walter (2000). "Prevention of Radiographic-Contrast-Agent–Induced Reductions in Renal Function by Acetylcysteine". New England Journal of Medicine. 343 (3): 180–4. doi:10.1056/NEJM200007203430304. PMID 10900277.

- ^ Hoffmann, U.; Fischereder, M; Krüger, B; Drobnik, W; Krämer, BK (2004). "The Value of N-Acetylcysteine in the Prevention of Radiocontrast Agent-Induced Nephropathy Seems Questionable". Journal of the American Society of Nephrology. 15 (2): 407–10. doi:10.1097/01.ASN.0000106780.14856.55. PMID 14747387.

- ^ Miner, S; Dzavik, V; Nguyen-Ho, P; Richardson, R; Mitchell, J; Atchison, D; Seidelin, P; Daly, P; Ross, J (2004). "N-acetylcysteine reduces contrast-associated nephropathy but not clinical events during long-term follow-up". American Heart Journal. 148 (4): 690–5. doi:10.1016/j.ahj.2004.05.015. PMID 15459602.

- ^ Marenzi, Giancarlo; Assanelli, Emilio; Marana, Ivana; Lauri, Gianfranco; Campodonico, Jeness; Grazi, Marco; De Metrio, Monica; Galli, Stefano; Fabbiocchi, Franco (2006). "N-Acetylcysteine and Contrast-Induced Nephropathy in Primary Angioplasty". New England Journal of Medicine. 354 (26): 2773–82. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa054209. PMID 16807414.

- ^ Kay, J.; Chow, WH; Chan, TM; Lo, SK; Kwok, OH; Yip, A; Fan, K; Lee, CH; Lam, WF (2003). "Acetylcysteine for Prevention of Acute Deterioration of Renal Function Following Elective Coronary Angiography and Intervention: A Randomized Controlled Trial". JAMA. 289 (5): 553. doi:10.1001/jama.289.5.553. PMID 12578487.

- ^ Smith, W. Thomas Jr. "Drug Thought To Protect Kidneys From Imaging Dye Doesn't Work" Medical News Today, 17 November 2010.

- ^ Kasielski, M; Nowak, D (2001). "Long-term administration of N-acetylcysteine decreases hydrogen peroxide exhalation in subjects with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease". Respiratory Medicine. 95 (6): 448–56. doi:10.1053/rmed.2001.1066. PMID 11421501.

- ^ Grandjean, E; Berthet, P; Ruffmann, R; Leuenberger, P (2000). "Efficacy of oral long-term -acetylcysteine in chronic bronchopulmonary disease: A meta-analysis of published double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trials". Clinical Therapeutics. 22 (2): 209–21. doi:10.1016/S0149-2918(00)88479-9. PMID 10743980.

- ^ Stey, C.; Steurer, J.; Bachmann, S.; Medici, T.C.; Tramèr, M.R (2000). "The effect of oral N-acetylcysteine in chronic bronchitis: a quantitative systematic review". European Respiratory Journal. 16 (2): 253–62. doi:10.1034/j.1399-3003.2000.16b12.x. PMID 10968500.

- ^ Poole, P.; Black, PN (2001). "Oral mucolytic drugs for exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: systematic review". BMJ. 322 (7297): 1271–4. doi:10.1136/bmj.322.7297.1271. PMC 31920. PMID 11375228.

- ^ Berk, Michael; Copolov, David; Dean, Olivia; Lu, Kristy; Jeavons, Sue; Schapkaitz, Ian; Anderson-Hunt, Murray; Judd, Fiona; Katz, Fiona (2008). "N-Acetyl Cysteine as a Glutathione Precursor for Schizophrenia—A Double-Blind, Randomized, Placebo-Controlled Trial". Biological Psychiatry. 64 (5): 361–8. doi:10.1016/j.biopsych.2008.03.004. PMID 18436195.

- ^ Berk, M; Copolov, D; Dean, O; Lu, K; Jeavons, S; Schapkaitz, I; Andersonhunt, M; Bush, A (2008). "N-Acetyl Cysteine for Depressive Symptoms in Bipolar Disorder—A Double-Blind Randomized Placebo-Controlled Trial". Biological Psychiatry. 64 (6): 468–75. doi:10.1016/j.biopsych.2008.04.022. PMID 18534556.

- ^ Kaneto, H.; Kajimoto, Y.; Miyagawa, J.; Matsuoka, T.; Fujitani, Y.; Umayahara, Y.; Hanafusa, T.; Matsuzawa, Y.; Yamasaki, Y. (1999). "Beneficial effects of antioxidants in diabetes: possible protection of pancreatic beta-cells against glucose toxicity". Diabetes. 48 (12): 2398–406. doi:10.2337/diabetes.48.12.2398. PMID 10580429.

- ^ Clinical trial number NCT00539513 for "N-Acetylcysteine Augmentation in Treatment-Refractory Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder" at ClinicalTrials.gov

- ^ Berk, M; Jeavons, S; Dean, OM; Dodd, S; Moss, K; Gama, CS; Malhi, GS (2009). "Nail-biting stuff? The effect of N-acetyl cysteine on nail-biting". CNS spectrums. 14 (7): 357–60. PMID 19773711.

- ^ Mardikian, P; Larowe, S; Hedden, S; Kalivas, P; Malcolm, R (2007). "An open-label trial of N-acetylcysteine for the treatment of cocaine dependence: A pilot study". Progress in Neuro-Psychopharmacology and Biological Psychiatry. 31 (2): 389–94. doi:10.1016/j.pnpbp.2006.10.001. PMID 17113207.

- ^ Larowe, S. D.; Myrick, H.; Hedden, S.; Mardikian, P.; Saladin, M.; McRae, A.; Brady, K.; Kalivas, P. W.; Malcolm, R. (2007). "Is Cocaine Desire Reduced by N-Acetylcysteine?". American Journal of Psychiatry. 164 (7): 1115–7. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.164.7.1115. PMID 17606664.

- ^ Pela, R.; Calcagni, A.M.; Subiaco, S.; Isidori, P.; Tubaldi, A.; Sanguinetti, C.M. (1999). "N-Acetylcysteine Reduces the Exacerbation Rate in Patients with Moderate to Severe COPD". Respiration. 66 (6): 495–500. doi:10.1159/000029447. PMID 10575333.

- ^ Breitkreutz, Raoul; Pittack, Nicole; Nebe, Carl Thomas; Schuster, Dieter; Brust, Jürgen; Beichert, Matthias; Hack, Volker; Daniel, Volker; Edler, Lutz (2000). "Improvement of immune functions in HIV infection by sulfur supplementation: Two randomized trials". Journal of Molecular Medicine. 78 (1): 55–62. doi:10.1007/s001090050382. PMID 10759030.

- ^ Ungheri, D; Pisani, C; Sanson, G; Bertani, A; Schioppacassi, G; Delgado, R; Sironi, M; Ghezzi, P (2000). "Protective effect of n-acetylcysteine in a model of influenza infection in mice". International journal of immunopathology and pharmacology. 13 (3): 123–128. PMID 12657201.

- ^ Kopke, Richard; Bielefeld, Eric; Liu, Jianzhong; Zheng, Jiefu; Jackson, Ronald; Henderson, Donald; Coleman, John (2005). "Prevention of impulse noise-induced hearing loss with antioxidants". Acta Oto-Laryngologica. 125 (3): 235–43. doi:10.1080/00016480410023038. PMID 15966690.

- ^ Acker-Mills, B., Robinette, M., LaPrath, A., and Kopke, R. (December, 2004). Effects of N-acetylcysteine on otoacoustic emissions following noise exposure. Proceedings of the 2004 Army Science Conference, Orlando, Florida. AD Number: ADA433105

- ^ De Flora, S.; Grassi, C.; Carati, L. (1997). "Attenuation of influenza-like symptomatology and improvement of cell-mediated immunity with long-term N-acetylcysteine treatment". European Respiratory Journal. 10 (7): 1535–41. doi:10.1183/09031936.97.10071535. PMID 9230243.

- ^ Bachert, C.; Hormann, K.; Mosges, R.; Rasp, G.; Riechelmann, H.; Muller, R.; Luckhaupt, H.; Stuck, B. A.; Rudack, C. (2003). "An update on the diagnosis and treatment of sinusitis and nasal polyposis". Allergy. 58 (3): 176–91. doi:10.1034/j.1398-9995.2003.02172.x. PMID 12653791.

- ^ Fawkes, SW CERI: Living with Alcohol Smart Drug News 1996 Dec 13

- ^ Resat Ozaras, Veysel Tahan, Seval Aydin, Hafize Uzun, Safiye Kaya, Hakan Senturk. N-acetylcysteine attenuates alcohol-induced oxidative stess in rats World Journal of Gastroenterology 2003 Apr 15

- ^ Fulghesu, A; Ciampelli, M; Muzj, G; Belosi, C; Selvaggi, L; Ayala, GF; Lanzone, A (2002). "N-acetyl-cysteine treatment improves insulin sensitivity in women with polycystic ovary syndrome". Fertility and Sterility. 77 (6): 1128–35. doi:10.1016/S0015-0282(02)03133-3. PMID 12057717.

- ^ Grant, J. E.; Odlaug, B. L.; Won Kim, S. (2009). "N-Acetylcysteine, a Glutamate Modulator, in the Treatment of Trichotillomania: A Double-blind, Placebo-Controlled Study". Archives of General Psychiatry. 66 (7): 756–63. doi:10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2009.60. PMID 19581567.

- ^ Adams, J. B.; Baral, M.; Geis, E.; Mitchell, J.; Ingram, J.; Hensley, A.; Zappia, I.; Newmark, S.; Gehn, E. (2009). "The Severity of Autism Is Associated with Toxic Metal Body Burden and Red Blood Cell Glutathione Levels". Journal of Toxicology. 2009: 1. doi:10.1155/2009/532640.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Ballatori, Nazzareno; Lieberman, Michael W.; Wang, Wei (1998). "N-Acetylcysteine as an Antidote in Methylmercury Poisoning". Environmental Health Perspectives. 106 (5): 267–71. doi:10.2307/3434014. PMC 1533084. PMID 9520359.

- ^ http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/1153370-overview

- ^ http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2210/9/7

- ^ Garrett, Christine E.; Prasad, Kapa (2004). "The Art of Meeting Palladium Specifications in Active Pharmaceutical Ingredients Produced by Pd-Catalyzed Reactions". Advanced Synthesis & Catalysis. 346: 889–900. doi:10.1002/adsc.200404071.

- ^ a b Palmer, Lisa A.; Doctor, Allan; Chhabra, Preeti; Sheram, Mary Lynn; Laubach, Victor E.; Karlinsey, Molly Z.; Forbes, Michael S.; MacDonald, Timothy; Gaston, Benjamin (2007). "S-Nitrosothiols signal hypoxia-mimetic vascular pathology". Journal of Clinical Investigation. 117 (9): 2592–601. doi:10.1172/JCI29444. PMC 1952618. PMID 17786245.

- ^ Hildebrandt, W.; Alexander, S; Bärtsch, P; Dröge, W (2002). "Effect of N-acetyl-cysteine on the hypoxic ventilatory response and erythropoietin production: linkage between plasma thiol redox state and O2 chemosensitivity". Blood. 99 (5): 1552–5. doi:10.1182/blood.V99.5.1552. PMID 11861267.

External links

- CIMS India database "[1]"

- N-acetylcysteine replenishes glutathione in HIV infection. "[2]"

- Stanislaus, Romesh; Gilg, Anne G; Singh, Avtar K; Singh, Inderjit (2005). "N-acetyl-L-cysteine ameliorates the inflammatory disease process in experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis in Lewis rats". Journal of Autoimmune Diseases. 2 (1): 4. doi:10.1186/1740-2557-2-4. PMC 1097751. PMID 15869713.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - British National Formulary 55, March 2008; ISBN 978 085369 776 3

- U.S. National Library of Medicine: Drug Information Portal - Acetylcysteine

- Research based information on Acetylcysteine as a nutritional supplement