Hank Williams

Hank Williams |

|---|

Hank Williams (September 17, 1923 – January 1, 1953), born Hiram King Williams, was an American singer-songwriter and musician regarded as one of the most important country music artists of all time. In the short period from 1947 until his death, at 29, on the first day of 1953, Williams recorded 35 singles (five of which were released posthumously) that would place in the Top 10 of the Billboard Country & Western Best Sellers chart, including eleven that ranked number one.

His father, Elonzo Williams, worked for the railway and was transferred often, so the family lived in several towns in southern Alabama. When Elonzo was hospitalized for eight years, the family was left to fend for themselves. Young Williams, whose own health was diminished owing to spina bifida, helped provide for his mother and sister. While the family was living in Georgiana, Alabama, Williams met Rufus "Tee-Tot" Payne, a black street performer who gave him guitar lessons in exchange for meals. Payne had a major influence on Williams's later musical style. During this time, Williams informally changed his name to Hank, believing it to be a better name for country music. While the family was living in Montgomery, Alabama, a teenaged Williams used to sing and play guitar on the sidewalk in front of the WSFA radio studios. He caught the attention of WSFA producers and started working there in 1937, singing and hosting a 15-minute program. He formed as backup the Drifting Cowboys band, which was managed by his mother, and dropped out of school to devote all of his time to his career. In 1941, when World War II broke, several members of the band were drafted. Williams, who was not taken because of his spina bifida, had trouble with their replacements. This, along with a burgeoning problem with alcohol as self-medication for his health problem, caused WSFA to fire him.

In 1943, Williams married Audrey Sheppard who, besides singing duets with him in his act, became his manager. After recording "Never Again" and "Honky Tonkin'" with Sterling Records, he signed a contract with MGM Records. In 1948, he released "Move it on Over," which became a hit. The same year, he joined the Louisiana Hayride radio program. In 1949, he released "Lovesick Blues," which carried him into the mainstream of music. After an initial rejection, Williams joined the Grand Ole Opry. He had 11 number one songs between 1948 and 1953, though he was unable to read or write music to any significant degree. His hits include "Your Cheatin' Heart," "Hey Good Lookin'," and "I'm So Lonesome I Could Cry." In 1952, Williams's consumption of alcohol, morphine and other painkillers to ease the pain resulting from his back condition caused problems in his personal and professional life. He divorced his wife and was fired by the Grand Ole Opry due to frequent drunkenness.On January 1, 1953, on the way to a concert, he had a doctor inject him with a combination of vitamin B12 and morphine, which, added to the alcohol and chloral hydrate that Williams had consumed earlier, caused him to have a fatal heart attack. He was only 29. Despite his short life, Hank Williams has had a major influence on country music.

His songs have been recorded by numerous artists, many of whom have also had hits with the tunes, in a range of pop, gospel, blues and rock styles. Williams has been covered by performers such as Willie Nelson, Townes Van Zandt, Bob Dylan, Leonard Cohen, Cake, Kenny Rankin, Beck Hansen, Johnny Cash, Tony Bennett, The Residents, Patsy Cline, Ray Charles, Louis Armstrong, and Tom Waits. He has received numerous honors and has been inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame.

Biography

Early life

Williams's parents, Elonzo Huble "Lon" Williams, who was of English ancestry,[1] and Jessie Lillybelle "Lillie" Skipper, were married on November 12, 1916, by Reverend J.C. Dunlap.

Elonzo Williams's mother, Anne Autrey Williams, had committed suicide when he was six years old, and his father died eleven years later. He lived the rest of his childhood in an orphanage. Williams left school in the sixth grade and started working as a waterboy in logging camps. He eventually became a engineer for the railroads of the W.T. Smith lumber company.

At the time of William's marriage proposal, Jessie Skipper lived near him on a farm owned by the Mixon family outside Georgiana, Alabama. Skipper had grown up in Georgiana. They lived for a time at the Mixon farm until they leased a cabin in the community of Mount Olive, Alabama. They opened a small store at a side of the house and also cultivated strawberries.

Elonzo Williams was drafted during World War I, serving from July 1918 until June 1919. He was severely injured after falling from a truck, breaking his collarbone and sustaining a severe hit to the head.

After Elonzo Williams returned from the war, the family's first child, Irene, was born on August 8, 1922.[2] A son died shortly after birth.

Hank Williams, Elonzo's and Lillie's third and last child together, was born on September 17, 1923, in Mount Olive. He was named after Hiram I of Tyre (one of the three founders of the Masons, according to Masonic legend), but his name was misspelled as "Hiriam" on his birth certificate.[1] As a child. he was nicknamed "Harm" by his family and "Herky" or "Skeets" by his friends. He was born with a mild undiagnosed case of spina bifida occulta, a disorder of the spinal column, which gave him lifelong pain—a factor in his later abuse of alcohol and drugs.[citation needed]

Williams's father was frequently relocated by his lumber company railway line employer. The family lived in many southern Alabama towns. In 1930, when Williams was seven years old, his father began suffering from facial paralysis. At a Veterans Affairs (VA) clinic in Pensacola, Florida, doctors determined that the cause was a brain aneurysm, and Elonzo was sent to the VA Medical Center in Alexandria, Louisiana. He remained hospitalized for eight years, rendering him mostly absent throughout Hiram's childhood.

From that time on, Lillie Williams assumed responsibility for the family. In 1933, Williams moved to Fountain, Alabama, to live with his uncle and aunt, Walter and Alice McNeil. In the fall of 1934, the Williams family moved to Greenville, Alabama, where Lillie opened a boarding house next to the Butler County courthouse. In 1937, Williams got into a fight with his physical education coach about exercises the coach wanted him to do. His mother subsequently demanded that the school board terminate the coach; when they refused, the family moved to Montgomery, Alabama.

In 1935, the Williams family settled in Garland, Alabama, where Lillie Williams opened a new boarding house. After a while, they moved with his cousin Opal McNeil to Georgiana, where Lillie managed to find several side jobs to support her children, despite the bleak economic climate of the Great Depression. She worked in a cannery and served as a night-shift nurse in the local hospital. Hiram and Irene also helped out by selling peanuts, shining shoes, delivering newspapers, and doing other simple jobs.

Their first house burned and the family lost all of their possessions. They moved to a new house on the other side of town on Rose Street, which Williams's mother soon turned into a boarding house. The house had a small garden, on which they grew diverse crops that Hank and his sister Irene sold around Georgiana. With the help of U.S. Representative J. Lister Hill, the family began collecting Elonzo's military disability pension. Despite his medical condition, the family managed fairly well financially throughout the Great Depression.[3] There are several versions of how Williams got his first guitar. His mother stated that she bought it with money from selling peanuts, but many other prominent residents of the town claimed to have been the one who purchased the guitar for him.

While living in Georgiana, Williams met Rufus "Tee-Tot" Payne, a street performer.[2] Payne gave Williams guitar lessons in exchange for meals prepared by Lillie Williams. Payne's base musical style was blues. He taught Williams chords, chord progressions, bass turns, and the style of accompaniment that he would use in most of his future song writing.[citation needed] Later on, Williams recorded one of the songs that Payne taught him, "My Bucket's Got a Hole In It."[4] Williams final style contained influences from Payne along with several other country influences, among them Jimmie Rodgers.[5] Payne and Williams lost touch in 1937 when the Williams family moved to Montgomery, Alabama. Payne also moved to Montgomery, where he died in poverty in 1939. Williams later credited him as his only teacher.[6]

Early career

In July 1937, the Williams and McNeil families opened a boarding house on South Perry Street in downtown Montgomery. It was at this time that Hiram decided to change his name informally to Hank, a name he said was better suited to his desired career in country music. After school and on weekends, Williams sang and played his Silvertone guitar on the sidewalk in front of the WSFA radio studios. He quickly caught the attention of WSFA producers, who occasionally invited him to perform on air. So many listeners contacted the radio station asking for more of the "singing kid" that the producers hired him to host his own 15-minute show twice a week for a weekly salary of US$15 (equivalent to US$230 in 2011[7]). One of the show's listeners was Alabama governor Bibb Graves.[1]

In August 1938, Elonzo Williams was temporarily released from the hospital. He showed up unannounced at the family's home in Montgomery. Lillie was unwilling to let him reclaim his position at the head of the household, so he stayed only long enough to celebrate Hank's birthday in September before he returned to the medical center in Louisiana.[2]

Williams's successful radio show fueled his entry into a music career. His salary was enough for him to start his own band, which he dubbed the Drifting Cowboys. The original members were guitarist Braxton Schuffert, fiddler Freddie Beach, and comic Smith "Hezzy" Adair. James E. (Jimmy) Porter was the youngest, being only 13 when he started playing steel guitar for Hank. Arthor Whiting was also a guitarist for The Drifting Cowboys. The band traveled throughout central and southern Alabama, performing in clubs and at private parties. Hank dropped out of school in October 1939 so that the Drifting Cowboys could work full time. James Ellis Garner later played fiddle for him. Lillie Williams stepped up and became the Drifting Cowboys' manager. She began booking show dates, negotiating prices, and driving them to some of their shows. Now free to travel without Hank's schooling taking precedence, the band could tour as far away as western Georgia and the Florida Panhandle. Meanwhile, Williams returned to Montgomery every weekday to host his radio show.

The American entry into World War II in 1941 marked the beginning of hard times for Williams. All his band members were drafted to serve in the military, and many of their replacements refused to continue playing in the band because of Hank's worsening alcoholism. He continued to show up for his radio show intoxicated, so in August 1942 WSFA fired him for "habitual drunkenness." He worked for the rest of the war in a shipbuilding company in Mobile, Alabama. During his time in Alabama, Williams met his idol, Grand Ole Opry star Roy Acuff,[8] who later warned him of the dangers of alcohol, saying: "You've got a million-dollar voice, son, but a ten-cent brain."[9]

1940s

In 1943, Williams met and married Audrey Sheppard, who became his manager as his career was rising (she also accompanied him on duets in some of his live concerts). Williams became a local celebrity. In 1945, when he was back in Montgomery, he published his first song book, Original Songs of Hank Williams and started to perform again for WSFA. On September 14, 1946, Williams auditioned for the Grand Ole Opry, but was rejected.

He signed a contract for six songs with Fred Rose. Rose obtained with those songs a contract for Williams with Sterling Records. On December 11, 1946, in his first recording session, he recorded "Wealth Won't Save Your Soul," "Calling You," "Never Again," and "When God Comes and Gathers his Jewels."[8] The recordings of "Never Again" and "Honky Tonkin'" were important successes.

Williams signed with MGM Records in 1947, and released "Move It On Over," a massive country hit. In August 1948, he joined Louisiana Hayride, a radio show broadcast from Shreveport, Louisiana, propelling him into living rooms all over the southeast.

After a few more moderate hits, in 1949, he released his version of Emmet Miller's composition "Lovesick Blues," made popular by Rex Griffin, which became a huge country hit and crossed over to mainstream audiences and gained Williams a place in the Grand Ole Opry.[10] On June 11, 1949, Williams made his debut at the Grand Ole Opry, where he became the first performer to receive six encores.[11] He brought together Bob McNett (guitar), Hillous Butrum (bass), Jerry Rivers (fiddle) and Don Helms (steel guitar) to form the most famous version of the Drifting Cowboys, earning an estimated US$1,000 per show (equivalent to US$927,692 in 2011[7]). That year, Audrey Williams gave birth to Randall Hank Williams (Hank Williams, Jr.).[12] 1949 also saw Williams release seven hit songs after "Lovesick Blues," including "Wedding Bells," "Mind Your Own Business," "You're Gonna Change (Or I'm Gonna Leave)," and "My Bucket's Got a Hole in It."[13]

1950s

Luke the Drifter

In 1950, Williams began recording as "Luke the Drifter" for his religious-themed recordings, many of which are recitations rather than singing. Fearful that disc jockeys and jukebox operators would hesitate to accept these nontraditional Williams recordings, thereby hurting the marketability of his name, the alias was employed.[14] Luke the Drifter was popular among black audiences primarily because of the song "The Funeral," in which Williams narrates, portraying a preacher at the funeral of a child in a black church.[15] The popularity of the song among black audiences was a response to the stereotypes of the characters depicted, inspired by Williams's teacher, Rufus Payne.[4] The songs of Luke the Drifter often depicted regional life and the philosophy of life.[16] The drifter moved around this region, narrating the stories of the characters.[17] Some of the compositions were accompanied by a tube organ and preached morality.[clarification needed] Allegedly, Williams created the alter ego also as a balance to his personality.[14]

Around this time, Williams released more hit songs, such as "My Son Calls Another Man Daddy," "They'll Never Take Her Love from Me," "Why Should We Try Any More?," "Nobody's Lonesome for Me," "Long Gone Lonesome Blues," "Why Don't You Love Me?," "Moanin' the Blues," and "I Just Don't Like This Kind of Livin'."[18] In 1951 "Dear John" became a hit, but it was the flip side, "Cold, Cold Heart," that became one of his most-recognized songs. A pop cover version by Tony Bennett released the same year stayed on the charts for 27 weeks, peaking at number one.[19]

Later career

In 1951, during a hunting trip in Tennessee, Williams fell, reactivating his old back pains, and he started to consume painkillers (including morphine) and alcohol to ease the pain.[12] His alcoholism worsened in 1952, and on August 11, 1952, Williams was fired from the Grand Ole Opry for habitual drunkenness. He returned to perform in KWKH shows and in the Louisiana Hayride, for which he toured again. His performances were acclaimed when he was sober, but despite the efforts of his work associates to get him to shows sober, his abuse of alcohol resulted in occasions when he did not appear or his performances were poor. Williams recorded "Kaw-Liga," along with "Your Cheatin' Heart" and "Take These Chains from My Heart" during his last session, on September 23, 1952.[20] Due to Williams's excesses, Fred Rose stopped working with him. Also, the Drifting Cowboys were at the time backing Ray Price, while Williams was backed by local bands.

By the end of 1952, Williams had started to suffer heart problems,[12] and he was prescribed chloral hydrate, a powerful sedative, to ease his pain by Dr. Horace Raphol "Toby" Marshall.[21]

Death

On December 31, 1952, Williams was scheduled to perform at the Municipal Auditorium in Charleston, West Virginia. Advance ticket sales totaled US$3,500 (equivalent to US$29,092 in 2011[7]). Because of an ice storm in the Nashville area, Williams could not fly, so he hired a college student, Charles Carr, to drive him to the concerts. Carr called the Charleston auditorium from Knoxville to say that Williams would not arrive on time owing to the ice storm and was ordered to drive Williams to Canton, Ohio for the New Year's Day concert there.[21]

Williams arrived at the Andrew Johnson Hotel in Knoxville, Tennessee, where Carr checked in at 7:08 p.m and ordered two steaks in the lobby. He also requested a doctor for Williams, as he was feeling the combination of the chloral hydrate and alcohol he had drunk on the way from Montgomery to Knoxville. Dr. P.H. Cardwell injected Williams with two shots of vitamin B12 that also contained a quarter-grain of morphine.[22] Carr and Williams checked out around 10:45 p.m. Hotel porters had to carry Williams to the car, as he was coughing and hiccupping.

When they crossed the West Virgina state line and arrived at Bluefield, West Virginia, Carr stopped at a restaurant and asked Williams if he wanted to eat. Williams said he did not, and those are believed to be his last words. Carr later drove on until he stopped at a gas station in Oak Hill, West Virginia, where he noticed Williams asleep in the back seat; he was unresponsive and his body was becoming rigid. Feeling Williams's pulse, Carr immediately realized that he was dead. Carr informed the filling station's owner, Glenn Burdette, who called the chief of the local police, O.H. Stamey. Because a corpse was involved, Stamey called in radio officer Howard Janney.[22] Stamey and Janney found some empty beer cans and the handwritten lyrics to a song yet to be recorded in the Cadillac convertible.[2]

Dr. Ivan Malinin, a Russian immigrant who barely spoke English, performed the autopsy at the Tyree Funeral House. Malinin found hemorrhages in the heart and neck and pronounced the cause of death as "insufficiency of the right ventricle of the heart." Apparently unrelated to Williams's death, Malinin found that he had also been severely kicked in the groin during a fight in a Montgomery bar a few days earlier[22] in which he had also injured his left arm, which was subsequently bandaged.[23]

That evening, when the announcer at Canton announced Williams's death to the gathered crowd, they started laughing, thinking that it was just another excuse. After Hawkshaw Hawkins and other performers started singing "I Saw the Light" as a tribute to Williams, the crowd, now realizing that he was indeed dead, followed them.[23]

The circumstances of Williams's death are still controversial. Some have claimed that Williams was dead before leaving Knoxville.[24] Oak Hill is still believed to be the place where Williams died,[3] but one of the more plausible theories states that Williams died in his sleep about 20 to 30 minutes before his car arrived in Oak Hill. There is a monument dedicated to his memory across the street from the gas station where Carr sought help.[25] The Cadillac in which Williams died is now preserved at the Hank Williams Museum in Montgomery, Alabama.[26]

The body was transported to Montgomery on January 2. It was placed in a silver coffin that was first shown at his mother's boarding house at 318 McDounough Street for two days.

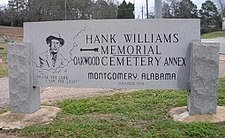

His funeral took place on January 4 at the Montgomery Auditorium, with his coffin placed on the flower-covered stage.[27] During the ceremony, Ernest Tubb sang "Beyond the Sunset" followed by Roy Acuff with "I Saw the Light" and Red Foley with "Peace in the Valley."[28] An estimated 15,000 to 25,000 people passed by the silver coffin, and the auditorium was filled with 2,750 mourners.[29] During the funeral, four women fainted and a fifth was carried off the auditorium in hysterics after falling at the foot of the casket.[28] His funeral was said to have been far larger than any ever held for any other citizen of Alabama and the largest event ever held in Montgomery.[30] Around two tons of flowers were sent.[22] Williams's remains are interred at the Oakwood Annex in Montgomery.

The president of MGM told Billboard magazine that the company got only about five requests for pictures of Williams during the weeks prior to his death, but over three hundred afterwards. The local record shops sold out of all of their records, and customers were asking for all records ever released by Williams.[29] His final single released during his lifetime was ironically titled "I'll Never Get Out of This World Alive."

"Your Cheatin' Heart" was written and recorded in 1952 but released in 1953 after Williams's death. The song was number one on the country charts for six weeks. It provided the title for the 1964 biographic film of the same name, which starred George Hamilton.[2]

-

Grave of Audrey (left) and Hank Williams (right) at Oakwood Annex Cemetery

-

Hank Williams's tombstone

-

Hank Williams's grave

Personal life

On December 15, 1944, Williams married Sheppard. It was her second marriage and his first. Their son, Randall Hank Williams, who would achieve fame in his own right as Hank Williams, Jr., was born on May 26, 1949. The marriage, always turbulent, rapidly disintegrated, and he developed a serious problem with alcohol, morphine and other painkillers prescribed for him to ease the severe back pain caused by his spina bifida. The couple divorced on May 29, 1952.[3] In June 1952, Williams moved in with his mother, even as he released numerous hit songs, such as "Half as Much," "Jambalaya (On the Bayou)," "Settin' the Woods on Fire," "You Win Again," and "I'll Never Get Out of This World Alive." His drug problems continued to spiral out of control as he moved to Nashville and officially divorced his wife. A relationship with Bobbie Jett during this period resulted in a daughter, Jett, who would be born five days after his death.[2][31]

On October 18, 1952, Williams and Billie Jean Jones Eshlimar were married in Minden in northwestern Louisiana[2] by a peace judge.[23] It was the second marriage for both (both having been divorced with children).[2] The next day, two public ceremonies were also held at the New Orleans Civic Auditorium, where 14,000 seats were sold for each.[23] It has been written that Williams wanted the two ceremonies in an attempt to spite Audrey, who wanted him back and threatened to never let him see his son again.[32] At this point, Williams's alcoholism and consumption of drugs had worsened; his new wife and friends tried to get him in rehabilitation, but they were not successful.[23]

After Williams's death, a judge ruled that the wedding was not legal because Billie Jean’s divorce had not become final until eleven days after she married Williams. Hank's first wife, Audrey, and his mother, Lillie, were the driving forces behind having the marriage declared invalid and pursued the matter for years.[3] Williams also married Audrey before her divorce was final, on the tenth day of a required sixty-day reconciliation period.[2]

Lawsuits over the estate

After Williams's death, Audrey Williams filled a suit in Nashville against MGM Records and Acuff-Rose. The suit demanded that both of the publishing companies continue to pay her half of the royalties from Hank Williams's records. Williams had an agreement giving his first wife half of the royalties, but there was no clarification that the deal was valid after his death. Because Williams had left no will, the disposition of the other fifty percent was also uncertain; those involved included the second Mrs. Williams and her daughter and Hank Williams's mother and sister.[33]

Billie Jean married country singer Johnny Horton in September 1953.[34] On October 22, 1975, a federal judge in Atlanta, Georgia, finally ruled Billie Jean's marriage was valid and that half of Williams's future royalties belonged to her.[35]

In February 2005, the Tennessee Court of Appeals upheld a lower court ruling stating that Williams's heirs—son Hank Williams Jr. and daughter Jett Williams—have the sole rights to sell his recordings made for a Nashville, Tennessee, radio station in 1951. The court rejected claims made by Polygram Records and Legacy Entertainment in releasing recordings Williams made for the Mother's Best Flour Show, a program that originally aired on WSM-AM. The recordings, which Legacy Entertainment acquired in 1997, include live versions of Williams's hits and his cover version of other songs. Polygram contended that Williams's contract with MGM Records, which Polygram now owns, gave them rights to release the radio recordings. A 3-CD selection of the tracks, restored by Joe Palmaccio, was released by Time-Life in October 2008 titled The Unreleased Recordings.[36]

Legacy

Williams had 11 number one hits in his career ("Lovesick Blues," "Long Gone Lonesome Blues," "Why Don't You Love Me," "Moanin' the Blues," "Cold, Cold Heart," "Hey Good Lookin'," "Jambalaya (On the Bayou)," "I'll Never Get Out of This World Alive," "Kaw-Liga," "Your Cheatin' Heart," and "Take These Chains from My Heart") as well as many other top ten hits.[37]

In 1987 Williams was inducted in the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame under the category Early Influence.[38] He was ranked second in CMT's 40 Greatest Men of Country Music in 2003, behind only Johnny Cash. His son, Hank Jr., was ranked on the same list.[39] In 2004, Rolling Stone ranked him number 74 on its list of the 100 Greatest Artists of All Time.[40] The website Acclaimedmusic, which collates recommendations of albums and recording artists, has a year-by-year recommendation for top artists. , Hank Williams is ranked first for the decade 1940–1949 for his song "I'm So Lonesome I Could Cry." Many rock and roll pioneers of the 1950s, such as Elvis Presley,[41] Bob Dylan, Jerry Lee Lewis, Merle Haggard,[42] Gene Vincent,[43] Carl Perkins,[44] Ricky Nelson,[45] Jack Scott,[46] Conway Twitty[47] recorded Williams songs early in their careers.

In 2011 Williams's 1949 MGM number one hit, "Lovesick Blues," was inducted into the Recording Academy Grammy Hall Of Fame.[48] The same year, Hank Williams: The Complete Mother’s Best Recordings….Plus! was honored with a Grammy nomination for Best Historical Album.[49] In 1999, Williams was inducted into the Native American Music Hall of Fame.[50] On April 12, 2010, the Pulitzer Prize Board awarded Williams a posthumous special citation that paid tribute to his "craftsmanship as a songwriter who expressed universal feelings with poignant simplicity and played a pivotal role in transforming country music into a major musical and cultural force in American life."[51]

In 1981, Drifting Cowboys steel guitarist Don Helms teamed up with Hank Williams, Jr. to record "The Ballad of Hank Williams." The track is a spoof or novelty song about Hank Sr.'s early years in the music business and his spending excesses. It was sung to the tune of "The Battle of New Orleans," popularized by Johnny Horton. Hank, Jr. begins by saying "Don, tell us how it really was when you was working with Daddy." Helms then goes into a combination of spoken word and song with Williams to describe how Hank, Sr. would "spend a thousand dollars on a hundred dollar show," among other humorous peculiarities. The chorus line "So he fired my ass and he fired Jerry Rivers and he fired everybody just as hard as he could go. He fired Old Cedric and he fired Sammy Pruett. And he fired some people that he didn't even know" is a comical reference to Hank Williams's overreaction to given circumstances.[52] In 1991, country artist Alan Jackson released "Midnight in Montgomery," a song whose lyrics portray meeting Hank Williams's spirit at Williams's gravesite while on his way to a New Year's Eve show.[23] Country artist Marty Stuart also paid homage to Williams with a tribute track entitled "Me And Hank And Jumping Jack Flash." The lyrics tell a story similar to the "Midnight in Montgomery" theme, but about an up-and-coming country music singer getting advice from Williams's spirit.[53] In 1983, country music artist David Allan Coe released "The Ride," a song that told a story of a young man with his guitar hitchhiking through Montgomery and being picked up by the ghost of Hank Williams in his Cadillac and driven to the edge of Nashville: "...You don't have to call me mister, mister, the whole world called me Hank."[54] Williams's son Hank Williams, Jr., daughter Jett Williams, grandson Hank Williams III, and granddaughters Hilary Williams and Holly Williams are also country musicians.[55]

Tributes

Awards

| Year | Award | Awards | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1989 | Grammy for Best Country Vocal Collaboration | Grammy | with Hank Williams, Jr. |

| 1989 | Music Video of the Year | CMA | with Hank Williams, Jr. |

| 1989 | Vocal Event of the Year | CMA | with Hank Williams, Jr. |

| 1989 | Video of the Year | Academy of Country Music | with Hank Williams, Jr. |

| 1990 | Vocal Collaboration of the Year | TNN/Music City News | with Hank Williams, Jr. |

| 1990 | Video of the Year | TNN/Music City News | with Hank Williams, Jr. |

| 2003 | Ranked No. 2 of the 40 Greatest Men of Country Music | CMT |

Music videos

| Year | Video | Director |

|---|---|---|

| 1989 | "There's a Tear in My Beer" (with Hank Williams, Jr.) | Ethan Russell |

| "Honky Tonk Blues" | ||

| 1996 | "Cold, Cold Heart | Buddy Jackson |

Discography

References

- ^ a b c Hemphill, Paul (2005). Lovesick Blues: The Life of Hank Williams. New York: Penguin Group. ISBN 0-670-03414-2.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Koon, George William (2002). Hank Williams, so lonesome. University of Mississippi press. ISBN 9781578062836. Retrieved March 6, 2011.

- ^ a b c d Williams, Roger M. (1981). Sing a sad song: the life of Hank Williams. University of Illinois Press. ISBN 9780252008610. Retrieved March 6, 2011.

- ^ a b Brackett, David (2000). Interpreting popular music. University of California Press. ISBN 9780520225411. Retrieved March 6, 2011.

- ^ Dicaire, David (2007). The first generation of country music stars: biographies of 50 artists born before 1940. McFarland. ISBN 9780786430215. Retrieved March 6, 2011.

- ^ "Rufus Payne, 1884-1939". The Alabama Historical Association. Retrieved March 6, 2011.

- ^ a b c "Consumer Price Index (Estimate) 1800–". The Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis. Retrieved March 14, 2011.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ a b Cusic, Don (2008). Discovering country music. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 9780313352454. Retrieved March 6, 2011.

- ^ Escott, Colin (1894), Hank Williams: The Biography, Boston: Little, Brown and Company, ISBN 0-316-24986-6

- ^ Browne, Pat (2001). The guide to United States popular culture. Popular Press. Retrieved March 6, 2011.

- ^ "Hank Williams, Sr., makes his Grand Ole Opry debut". History.com. Retrieved March 7, 2011.

- ^ a b c "Hank Williams Biography". AOL Music. AOL. Retrieved March 7, 2011.

- ^ Young, William H.; Young, Nancy K. (2010). World War II and the Postwar Years in America: A Historical and Cultural Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 9780313356520. Retrieved March 7, 2011.

- ^ a b Ching, Barbara (2003). Wrong's What I Do Best: Hard Country Music and Contemporary Culture. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780195169423. Retrieved March 7, 2011.

- ^ Tosches, Nick (1996). Country: the twisted roots of rock 'n' roll. Da Capo Press. ISBN 9780306807138. Retrieved March 7, 2011.

- ^ Bernstein, Cynthia Goldin; Nunnally, Thomas; Sabino, Robin (1997). Language variety in the South revisited. University of Alabama Press. ISBN 9780817308827.

{{cite book}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ^ Peppiatt, Francesca (2004). Country Music's Most Wanted: The Top 10 Book of Cheatin' Hearts, Honky-Tonk Tragedies, and Music City Oddities. Brassey's. ISBN 9781574885934. Retrieved March 7, 2011.

- ^ "Billboard Jan 13, 1951". Billboard. Jan 13, 1951. ISSN 0006-2510. Retrieved March 7, 2011.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Whitburn, Joel (1973). Top pop records, 1940-1955. Record Research Billboard. ISBN 089820092.

{{cite book}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help); Check|isbn=value: length (help) - ^ Lornell, Kip; Laird, Tracey (2008). Shreveport sounds in black and white. Univ. Press of Mississippi. Retrieved March 7, 2011.

- ^ a b Lilly, John. "Hank's Lost Charleston Show". West Virginia Division of Culture and History. Retrieved March 8, 2011.

- ^ a b c d Olson, Ted (2004). Crossroads: A Southern Culture Annual. Mercer University Press. ISBN 9780865548664. Retrieved March 8, 2011.

- ^ a b c d e f Celon, Curtis W. (1995). Country music culture: from hard times to Heaven. Univ. Press of Mississippi. Retrieved March 8, 2011.

- ^ Neely, Jack. "Hank Williams's Knoxville demise surrounded by mystery half a century later". Archived from the original on 2003-03-11. Retrieved March 8, 2011.

- ^ "Hank Williams Memorial Plaque Herbert E. Jones Library Oak Hill, West Virginia". HankWilliams.WS. Retrieved March 8, 2011.

- ^ "Hank Williams Museum". The Hank Williams Museum. Retrieved March 8, 2011.

- ^ Stanton, Scott (2003). The tombstone tourist: musicians. Simon & Schuster. ISBN 9780743463300.

{{cite book}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help); External link in|title= - ^ a b Hefley, James C. Country Music Comin' Home.

{{cite book}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help); External link in|title= - ^ a b Peterson, Richard A. (1997). Creating country music: fabricating authenticity. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 9780226662848. Retrieved March 8, 2011.

- ^ Hank Williams Trail Brouchure.

{{cite book}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help);|work=ignored (help); External link in|title= - ^ "Jett Williams Biography". Jett Williams.com. Retrieved March 8, 2011.

- ^ Escott, Colin; Merritt, George; MacEwen, William (2004). Hank Williams: The Biography. Back Bay. p. 241. ISBN 978-0-316-73497-4.

- ^ "Billboard May 23, 1953". Billboard. Nielsen. ISSN 0006-2510.

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help); External link in|title= - ^ "RAB Hall of Fame: Johnny Horton". Rockabilly Hall of Fame. Retrieved March 8, 2011.

- ^ Koon, George William (1983). Hank Williams: a bio-bibliography. Greenwood Press. ISBN 9780313229824.

{{cite book}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help); line feed character in|title=at position 15 (help) - ^ Hilbourn, Robert (October 28, 2008). "There's Plenty Cookin'". LAtimes.com. Retrieved March 14, 2011.

- ^ George-Warren; Romanowski, Patricia; Romanowski Bashe, Patricia; Pareles, Jon (2001). The Rolling stone encyclopedia of rock & roll. Fireside. ISBN 9780743201209.

{{cite book}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ^ "Hank Williams". Rock and Roll Hall of Fame. Retrieved March 15, 2011.

- ^ "CMT 40 GREATEST MEN OF COUNTRY MUSIC". CMT. Retrieved March 14, 2011.

- ^ "100 Greatest Artists of All Time". Rolling Stone Issue 946. Rolling Stone.

- ^ "Elvis Presley". Allmusic. Retrieved March 14, 2011.

- ^ "Hank Williams". Allmusic. Retrieved March 14, 2011.

- ^ "Gene Vincent". Allmusic. Retrieved March 14, 2011.

- ^ "Carl Perkins". Allmusic. Retrieved March 14, 2011.

- ^ "Ricky Nelson". Allmusic. Retrieved March 14, 2011.

- ^ "Jack Scott". Allmusic. Retrieved March 14, 2011.

- ^ "Conway Twitty". Allmusic. Retrieved March 14, 2011.

- ^ "HANK WILLIAMS RECEIVES ADDITIONAL GRAMMY RECOGNITION AS "LOVESICK BLUES" INDUCTED INTO GRAMMY HALL OF FAME". rodeoattitude.com. Retrieved March 14, 2011.

- ^ "THE BEATLES' CATALOGUE WINS 'BEST HISTORICAL ALBUM' GRAMMY". WMMR. February 14, 2011. Retrieved March 14, 2011.

- ^ "Hank Williams: Native American group Inducts Him". Herald-Journal. 9 November 1999. Retrieved 25 June 2010.

- ^ "The 2010 Pulitzer Prize Winners Special Awards and Citations". April 12, 2010. Retrieved 2010-04-12.

- ^ Larkin, Colin (1998). The Virgin encyclopedia of country music. Virgin. ISBN 9780753502365.

{{cite book}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ^ Escott,, Colin; Florita, Kira (2001). Hank Williams: snapshots from the lost highway. Da Capo.

{{cite book}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help)CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) - ^ Tichi, Cecelia (1998). Reading country music: steel guitars, opry stars, and honky-tonk bars. Duke University Press. ISBN 978-0822321682. Retrieved March 14, 2011.

- ^ "New exhibit explores Hank Williams's family legacy". Associated Press. Yahoo!. April 17, 2008. Retrieved March 14, 2011.

Further reading

- Caress, Jay (1979), Hank Williams, Stein and Day, ISBN 9780812825831

- Escott, Colin; Merritt, George; MacEwen, William (2004), Hank Williams: The Biography, Back Bay, ISBN 9780316734974

- Hemphill, Paul (2005), Lovesick Blues: The Life of Hank Williams, Viking, ISBN 9780670034147

- Koon, George William (1983), Hank Williams: a Bio-bibliography, Greenwood Press, ISBN 9780313229824

- Koon, George William; Koon, Bill (2001), Hank Williams, So Lonesome, University Press of Mississippi, ISBN 9781578062836

- Williams, Lycrecia; Vinicur, Dale (1991), Still in Love with You: Hank and Audrey Williams, Thomas Nelson Incorporated, ISBN 9781558531055

- Williams, Roger M. (1981), Sing a Sad Song: The Life of Hank Williams, University of Illinois Press, ISBN 9780252008610

- Rivers, Jerry (1967), Hank Williams: From Life to Legend, Jerry Rivers

{{citation}}: Unknown parameter|library of congress catalog=ignored (help)

External links

- Official website

- Hank Williams at IMDb

- Hank Williams at AllMusic

- Hankville fan website

- Williams's boyhood home and museum

- at the Country Music Hall of Fame – 1961 Inductee

- at the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame – 1987 Inductee

- at the Alabama Music Hall of Fame – 1985 Inductee

- PBS – American Masters

- Sites related to final day

- Williams article, Encyclopedia of Alabama

- A Hank Williams Discography

- Listing of all Williams's songs and alternatives

- 'Hank Williams: The Show He Never Gave'

- Hank Williams “Revealed: The Unreleased Recordings” Time Life review on CountryMusicPride.com

- 1923 births

- 1953 deaths

- People from Jefferson County, Alabama

- Baptists from the United States

- American country guitarists

- American country singer-songwriters

- American male singers

- American buskers

- Country Music Hall of Fame inductees

- Rock and Roll Hall of Fame inductees

- Songwriters Hall of Fame inductees

- Grand Ole Opry members

- People from Montgomery, Alabama

- Musicians from Alabama

- American people of English descent

- MGM Records artists

- Grammy Award winners

- People with spina bifida

- Drug-related deaths in West Virginia

- Alcohol-related deaths in West Virginia

- Pulitzer Prize winners