Russo-Japanese War

| Russo-Japanese War | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 500,000 [citation needed] | 300,000 [citation needed] | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

34,000 – 52,623 killed and died of wounds 9,300 – 18,830 died of disease 146,032 wounded 74,369 captured 50,688 deadweight loss[1][2] |

47,400 – 47,152 killed 11,424 – 11,500 died of wounds 21,802 – 27,200 died of disease[1][2] | ||||||

The Russo-Japanese War (Japanese: 日露戦争; Romaji: Nichi-Ro Sensō; Russian: Русско-японская война Russko-yaponskaya voyna; simplified Chinese: 日俄战争; traditional Chinese: 日俄戰爭; pinyin: Rì'é Zhànzhēng, 8 February 1904 – 5 September 1905) was "the first great war of the 20th century"[3] which grew out of the rival imperial ambitions of the Russian Empire and Japanese Empire over Manchuria and Korea. The major theatres of operations were Southern Manchuria, specifically the area around the Liaodong Peninsula and Mukden, the seas around Korea, Japan, and the Yellow Sea.

The Russians sought a warm water port[4] on the Pacific Ocean, for their navy as well as for maritime trade. Vladivostok was only operational during the summer season, but Port Arthur would be operational all year. From the end of the First Sino-Japanese War and 1903, negotiations between Russia and Japan had proved impractical. Japan chose war to maintain dominance in Korea.

The resulting campaigns, in which the Japanese military attained victory over the Russian forces arrayed against them, were unexpected by world observers. As time transpired, these victories would transform the balance of power in East Asia, resulting in a reassessment of Japan's recent entry onto the world stage. The embarrassing string of defeats inflamed the Russian people's dissatisfaction with their inefficient and corrupt Tsarist government, and proved a major cause of the Russian Revolution of 1905.

Origins of the Russo-Japanese war

After the Meiji Restoration in 1868, the Meiji government embarked on an endeavor to assimilate Western ideas, technological advances and customs. By the late 19th century, Japan had emerged from isolation and transformed itself into a modernized industrial state in less than half a century. The Japanese wished to preserve their sovereignty and to be recognized as an equal with the Western powers.

Russia, a major Imperial power, had ambitions in the East. By the 1890s it had extended its realm across Central Asia to Afghanistan, absorbing local states in the process. The Russian Empire stretched from Poland in the west to the Kamchatka peninsula in the East.[5] With its construction of the Trans-Siberian Railway to the port of Vladivostok, Russia hoped to further consolidate its influence and presence in the region. This was precisely what Japan feared, as they regarded Korea (and to a lesser extent Manchuria) as a protective buffer.

Sino-Japanese War (1894–1895)

The Japanese government regarded Korea, which was close to Japan, as an essential part of its national security; Japan's population explosion and economic needs were also factored into Japanese foreign policy. At the very least, the Japanese wanted to keep Korea independent, if not under Japanese influence. Japan's subsequent victory over China during the First Sino-Japanese War led to the Treaty of Shimonoseki under which China abandoned its own suzerainty over Korea and ceded Taiwan, Pescadores and the Liaodong Peninsula (Port Arthur) to Japan.

However, the Russians, having their own ambitions in the region persuaded Germany and France to apply pressure on Japan. Through the Triple Intervention, Japan relinquished its claim on the Liaodong Peninsula for an increased financial indemnity.

Russian encroachment

In December 1897, a Russian fleet appeared off Port Arthur. After three months, in 1898, a convention was agreed between China and Russia by which Russia was leased Port Arthur, Talienwan and the surrounding waters. It was further agreed that the convention could be extended by mutual agreement. The Russians clearly believed that would be the case for they lost no time in occupation and in fortifying Port Arthur, their sole warm-water port on the Pacific coast, and of great strategic value. A year later, in order to consolidate their position, the Russians began a new railway from Harbin through Mukden to Port Arthur. The development of the railway was a contributory factor to the Boxer Rebellion and the railway stations at Tiehling and Lioyang were burned. The Russians also began to make inroads into Korea. By 1898 they had acquired mining and forestry concessions near Yalu and Tumen rivers,[6] causing the Japanese much anxiety. Japan decided to strike before the Trans-Siberian Railway was complete.

The Boxer Rebellion

The Russians and the Japanese were both part of the eight member international force which was sent in 1900 to quell the Boxer Rebellion and to relieve the international legations under siege in the Chinese capital. As with other member nations, the Russians sent troops into Beijing. Russia had already sent 177,000 soldiers to Manchuria, nominally to protect its railways under construction. The troops of the Qing empire and the participants of the Boxer Rebellion could do nothing against this massive army. As a result, the Qing troops were ejected from Manchuria and the Russian troops settled in.[7] Russia assured the other powers that it would vacate the area after the crisis. However, by 1903, the Russians had not yet established any timetable for withdrawal[8] and had actually strengthened their position in Manchuria.

Pre-war negotiations

The Japanese statesman, Itō Hirobumi, started to negotiate with the Russians. He believed that Japan was too weak to evict Russia militarily, so he proposed giving Russia control over Manchuria in exchange for Japanese control of northern Korea. Meanwhile, Japan and Britain had signed the Anglo-Japanese Alliance in 1902, the British seeking to restrict naval competition by keeping the Russian Pacific seaports of Vladivostok and Port Arthur from their full use. The alliance with the British meant, in part, that if any nation allied itself with Russia during any war with Japan, then Britain would enter the war on Japan's side. Russia could no longer count on receiving help from either Germany or France without there being a danger of the British involvement with the war. With such an alliance, Japan felt free to commence hostilities, if necessary.

On 28 July 1903, the Japanese Minister in St. Petersburg was instructed to present his country's view opposing Russia's consolidation plans in Manchuria. On August 12, the Japanese minister handed the following document to serve as the basis for further negotiations:

- "1. Mutual engagement to respect the independence and territorial integrity of the Chinese and Korean Empires and to maintain the principle of equal opportunity for the commerce and industry of all nations in those countries.

- 2. Reciprocal recognition of Japan's preponderating interests in Korea and Russia's special interests in railway enterprises in Manchuria, and of the right of Japan to take in Korea and of Russia to take in Manchuria such measures as may be necessary for the protection of their respective interests as above defined, subject, however, to the provisions of Article I of this Agreement.

- 3. Reciprocal undertaking on the part of Russia and Japan not to impede development of those industrial and commercial activities respectively of Japan in Korea and of Russia in Manchuria, which are not inconsistent with the stipulations of Article I of this Agreement. Additional engagement on the part of Russia not to impede the eventual extension of the Korean railway into southern Manchuria so as to connect with the East China and Shan-hai-kwan-Newchwang lines.

- 4. Reciprocal engagement that in case it is found necessary to send troops by Japan to Korea, or by Russia to Manchuria, for the purpose either of protecting the interests mentioned in Article II of this Agreement, or of suppressing insurrection or disorder calculated to create international complications, the troops so sent are in no case to exceed the actual number required and are to be forthwith recalled as soon as their missions are accomplished.

- 5. Recognition on the part of Russia of the exclusive right of Japan to give advice and assistance in the interest of reform and good government in Korea, including necessary military assistance.

- 6. This Agreement to supplant all previous arrangements between Japan and Russia respecting Korea".[9]

On October 3, the Russian Minister to Japan, Roman Rosen, presented the Japanese government the Russian counter-proposal as the basis of negotiations, as follows:

- "1. Mutual engagement to respect the independence and territorial integrity of the Korean Empire.

- 2. Recognition by Russia of Japan's preponderating interests in Korea and of the right of Japan to give advice and assistance to Korea tending to improve the civil administration of the Empire without infringing the stipulations of Article I.

- 3. Engagement on the part of Russia not to impede the commercial and industrial undertakings of Japan in Korea, nor to oppose any measures taken for the purpose of protecting them so long as such measures do not infringe the stipulations of Article I.

- 4. Recognition of the right of Japan to send for the same purpose troops to Korea, with the knowledge of Russia, but their number not to exceed that actually required, and with the engagement on the part of Japan to recall such troops as soon as their mission is accomplished.

- 5. Mutual engagement not to use any part of the territory of Korea for strategical purposes nor to undertake on the coasts of Korea any military works capable of menacing the freedom of navigation in the Straits of Korea.

- 6. Mutual engagement to consider that part of the territory of Korea lying to the north of the 39th parallel as a neutral zone into which neither of the Contracting Parties shall introduce troops.

- 7. Recognition by Japan of Manchuria and its littoral as in all respects outside her sphere of interest.

- 8. This agreement to supplant all previous Agreements between Russia and Japan respecting Korea".[10]

Negotiations followed and, on 13 January 1904, Japan proposed a formula by which Manchuria would be outside the Japanese sphere of influence and, reciprocally, Korea outside Russia's. By 4 February 1904, no formal reply had been received and on 6 February Kurino Shinichiro, the Japanese Minister, called on the Russian Foreign Minister, Count Lambsdorff, to take his leave.[11] Japan severed diplomatic relations with Russia on 6 February 1904.

This situation arose from the arrogance of the Tsar, Nicholas II, who thought to use the war against Japan as a spark for the revival of Russian patriotism. His advisors did not support the war against Japan, foreseeing problems in transporting troops and supplies from European Russia to the East.[12] This attitude by the Tsar led to repeated delays in negotiations with the Japanese government. The Japanese understanding of this can be seen from a telegram dated December 1, 1903 from Japanese Minister of Foreign Affairs Komura to the Minister to Russia, in which he stated:

"the Japanese Government have at all times during the progress of the negotiations made it a special point to give prompt answers to all propositions of the Russian Government. The negotiations have now been pending for no less than four months, and they have not yet reached a stage where the final issue can with certainty be predicted. In these circumstances the Japanese government cannot but regard with grave concern the situation for which the delays in negotiations are largely responsible".[13]

The assertion that the Tsar intentionally dragged Japan into war in hopes of reviving Russian nationalism it is, however, disputed by Tsar Nicholas II's comment that "there will be no war because I do not wish it".[14] This does not reject the claim that Russia played an aggressive role in the East, which it did, rather that Russia unwisely predicted that Japan would not go to war due to Russia's far larger and seemingly superior navy and army. Evidence of Russia's false sense of security and superiority to the Japanese is seen by their reference to the latter as an "infantile monkey".[15]

This article needs additional citations for verification. (August 2010) |

Declaration of war

Japan issued a declaration of war on 8 February 1904.[16] However, three hours before Japan's declaration of war was received by the Russian Government, the Imperial Japanese Navy attacked the Russian Far East Fleet at Port Arthur. Tsar Nicholas II was stunned by news of the attack. He could not believe that Japan would commit an act of war without a formal declaration, and had been assured by his ministers that the Japanese would not fight. Russia declared war on Japan eight days later.[17] However, the requirement to declare war before commencing hostilities was not made international law until after the war had ended, in October 1907, effective from 26 January 1910.[18] Montenegro also declared war against Japan as a gesture of moral support for Russia out of gratitude for Russian support in Montenegro's struggles against the Ottoman Empire. However, for reasons of logistics and distance, Montenegro's contribution to the war effort was limited to the presence of Montenegrins serving in the Russian armed forces. The Qing empire favoured the Japanese position and even offered military aid, but Japan declined it. However, Yuan Shikai sent envoys to Japanese generals several times to deliver foodstuffs and alcoholic drinks. Native Manchurians joined the war on both sides as hired troops.

Campaign of 1904

Port Arthur, on the Liaodong Peninsula in the south of Manchuria, had been fortified into a major naval base by the Imperial Russian Army. Since it needed to control the sea in order to fight a war on the Asian mainland, Japan's first military objective was to neutralize the Russian fleet at Port Arthur.

Battle of Port Arthur

On the night of 8 February 1904, the Japanese fleet under Admiral Togo Heihachiro opened the war with a surprise torpedo boat destroyer[19] attack on the Russian ships at Port Arthur. The attack badly damaged the Tsesarevich and Retvizan, the heaviest battleships in Russia's far Eastern theater, and the 6,600 ton cruiser Pallada.[20] These attacks developed into the Battle of Port Arthur the next morning. A series of indecisive naval engagements followed, in which Admiral Togo was unable to attack the Russian fleet successfully as it was protected by the shore batteries of the harbor, and the Russians were reluctant to leave the harbor for the open seas, especially after the death of Admiral Stepan Osipovich Makarov on 13 April 1904.

However, these engagements provided cover for a Japanese landing near Incheon in Korea. From Incheon the Japanese occupied Seoul and then the rest of Korea. By the end of April, the Imperial Japanese Army under Kuroki Itei was ready to cross the Yalu river into Russian-occupied Manchuria.

Battle of Yalu River

In contrast to the Japanese strategy of rapidly gaining ground to control Manchuria, Russian strategy focused on fighting delaying actions to gain time for reinforcements to arrive via the long Trans-Siberian railway which was at the time incomplete near Irkutsk. On 1 May 1904, the Battle of Yalu River became the first major land battle of the war; Japanese troops stormed a Russian position after crossing the river. The defeat of the Russian Eastern Detachment removed the perception that the Japanese would be an easy enemy, that the war would be short, and that Russia would be the overwhelming victor.[21] Japanese troops proceeded to land at several points on the Manchurian coast, and in a series of engagements drove the Russians back towards Port Arthur. The subsequent battles, including the Battle of Nanshan on 25 May 1904, were marked by heavy Japanese losses largely from attacking entrenched Russian positions.

Blockade of Port Arthur

The Japanese attempted to deny the Russians use of Port Arthur. During the night of 13 February – 14 February, the Japanese attempted to block the entrance to Port Arthur by sinking several cement-filled steamers in the deep water channel to the port,[22] but they sank too deep to be effective. A similar attempt to block the harbor entrance during the night of 3–4 May also failed. In March, the charismatic Vice Admiral Makarov had taken command of the First Russian Pacific Squadron with the intention of breaking out of the Port Arthur blockade.

On 12 April 1904, two Russian pre-dreadnought battleships, the flagship Petropavlovsk and the Pobeda slipped out of port but struck Japanese mines off Port Arthur. The Petropavlovsk sank almost immediately, while the Pobeda had to be towed back to port for extensive repairs. Admiral Makarov, the single most effective Russian naval strategist of the war, perished on the battleship Petropavlovsk.

On 15 April 1904, the Russian government made overtures threatening to seize the British war correspondents who were taking the ship Haimun into warzones to report for the London-based Times newspaper, citing concerns about the possibility of the British giving away Russian positions to the Japanese fleet.

The Russians learned quickly, and soon employed the Japanese tactic of offensive minelaying. On 15 May 1904, two Japanese battleships, the Yashima and the Hatsuse, were lured into a recently laid Russian minefield off Port Arthur, each striking at least two mines. The Hatsuse sank within minutes, taking 450 sailors with her, while the Yashima sank while under tow towards Korea for repairs. On June 23, 1904, a breakout attempt by the Russian squadron, now under the command of Admiral Wilgelm Vitgeft failed. By the end of the month, Japanese artillery were firing shells into the harbor.

Anglo-Japanese intelligence co-operation

Even before the war, British and Japanese intelligence had co-operated against Russia.[23] Indian Army stations in Malaya and China often intercepted and read wireless and telegraph cable traffic relating to the war, which was shared with the Japanese.[24] In their turn, the Japanese shared information about Russia with the British with one British official writing of the "perfect quality" of Japanese intelligence.[25] In particular, British and Japanese intelligence gathered much evidence that Germany was supporting Russia in the war as part of a bid to disturb the balance of power in Europe, which led to British officials increasingly perceiving that country as a threat to the international order.[26]

Siege of Port Arthur

Japan began a long siege of Port Arthur. On 10 August 1904, the Russian fleet again attempted to break out and proceed to Vladivostok, but upon reaching the open sea were confronted by Admiral Togo's battleship squadron. The situation was critical for the Japanese, for they had only one battleship fleet and had already lost two battleships to Russian mines. Admiral Togo knew that another Russian battleship fleet would soon be sent to the Pacific. The Russian and Japanese battleships exchanged fire, until the Russian flagship, the battleship Tsesarevich, received a direct hit on the bridge, killing the fleet commander, Admiral Vitgeft. At this, the Russian fleet turned around and headed back into Port Arthur. Though no warships were sunk by either side in the battle, the Russians were now back in port and the Japanese navy still had battleships to meet the new Russian fleet when it arrived.

As the siege of Port Arthur continued, Japanese troops tried numerous frontal assaults on the fortified hilltops overlooking the harbor, which were defeated with Japanese casualties in the thousands. Eventually, though, with the aid of several batteries of 11-inch (280 mm) Krupp howitzers, the Japanese were finally able to capture the key hilltop bastion in December 1904. From this vantage point, the long-range artillery was able to shell the Russian fleet, which was unable to retaliate effectively against the land-based artillery and was unable or unwilling to sortie out against the blockading fleet. Four Russian battleships and two cruisers were sunk in succession, with the fifth and last battleship being forced to scuttle a few weeks later. Thus, all capital ships of the Russian fleet in the Pacific were sunk. This is likely the only example in military history when such a scale of devastation was achieved by land-based artillery against major warships.

Meanwhile, on land, attempts to relieve the besieged city by land also failed, and, after the Battle of Liaoyang in late August, the northern Russian force that might have been able to relieve Port Arthur retreated to Mukden (Shenyang). Major General Anatoly Stessel, commander of the Port Arthur garrison, believed that the purpose of defending the city was lost after the fleet had been destroyed. Several large underground mines were exploded in late December, resulting in the costly capture of a few more pieces of the defensive line. Nevertheless, the Russian defenders were effecting disproportionate casualties each time the Japanese attacked, and the garrison was still well stocked with months of food and ammunition[citation needed]. Despite this, Stessel decided to surrender to the surprised Japanese generals on 2 January 1905. He made this decision without consulting the other military staff present, or of the Tsar and military command, who all disagreed with the decision. Stessel was convicted by a court-martial in 1908 and sentenced to death for his incompetent defense and disobeying orders, though he was later pardoned.

Baltic Fleet redeploys

Meanwhile, at sea, the Russians were preparing to reinforce their Far East Fleet by sending the Baltic Fleet, under the command of Admiral Zinovy Rozhestvensky. The squadron sailed half way around the world from the Baltic Sea to the Pacific via the Cape of Good Hope. After a port of call at Madagascar, then Cam Ranh Bay (later part of South Vietnam), Rozhestvensky finally reached the Far East in May 1905. On 21 October 1904, while steaming past Great Britain (an ally of Japan, but neutral, unless provoked by a non-combatant nation), vessels of the Russian fleet nearly induced war with Britain in the Dogger Bank incident by firing on British fishing boats that they mistook for enemy torpedo boats; an incident they could hardly have been faulted for, for as early as the Spanish-American War in 1898, American sailors had also "...came to see torpedo boats as ghosts, and the men fired at rocks, ocean swells, and at trains on shore...each man believing they had seen torpedo boats..."[27]

Campaign of 1905

With the fall of Port Arthur, the Japanese 3rd army was now able to continue northward and reinforce positions south of Russian-held Mukden. With the onset of the severe Manchurian winter, there had been no major land engagements since the Battle of Shaho the previous year. The two sides camped opposite each other along 60 to 70 miles (110 km) of front lines, south of Mukden.

Battle of Sandepu

The Russian Second Army under General Oskar Grippenberg, between January 25–29, attacked the Japanese left flank near the town of Sandepu, almost breaking through. This caught the Japanese by surprise. However, without support from other Russian units the attack stalled, Grippenberg was ordered to halt by Kuropatkin and the battle was inconclusive. The Japanese knew that they needed to destroy the Russian army in Manchuria before Russian reinforcements arrived via the Trans-Siberian railroad.

Battle of Mukden

The Battle of Mukden commenced on 20 February 1905. In the following days Japanese forces proceeded to assault the right and left flanks of Russian forces surrounding Mukden, along a 50-mile (80 km) front. Both sides were well entrenched and were backed by hundreds of artillery pieces. After days of harsh fighting, added pressure from the flanks forced both ends of the Russian defensive line to curve backwards. Seeing they were about to be encircled, the Russians began a general retreat, fighting a series of fierce rearguard actions, which soon deteriorated in the confusion and collapse of Russian forces. On 10 March 1905 after three weeks of fighting, General Kuropatkin decided to withdraw to the north of Mukden.

The retreating Russian Manchurian Army formations disbanded as fighting units, but the Japanese failed to destroy them completely. The Japanese themselves had suffered large casualties and were in no condition to pursue. Although the battle of Mukden was a major defeat for the Russians it was not decisive, and the final victory still depended on the navy.

Battle of Tsushima

The Russian Second Pacific Squadron (the renamed Baltic Fleet) sailed 18,000 nautical miles (33,000 km) to relieve Port Arthur. The demoralizing news that Port Arthur had fallen reached the fleet while at Madagascar. Admiral Rozhestvensky's only hope now was to reach the port of Vladivostok. There were three routes to Vladivostok, with the shortest and most direct passing through Tsushima Straits between Korea and Japan. However, this was also the most dangerous route as it passed very close to the Japanese home islands.

Admiral Togo was aware of Russian progress and understood that with the fall of Port Arthur, the Second and Third Pacific Squadrons would try to reach the only other Russian port in the Far East, Vladivostok. Battle plans were laid down and ships were repaired and refitted to intercept the Russian fleet.

The Japanese Combined Fleet, which had originally consisted of six battleships, was now down to four (two had been lost to mines), but still retained its cruisers, destroyers, and torpedo boats. The Russian Second Pacific Squadron contained eight battleships, including four new battleships of the Borodino class, as well as cruisers, destroyers and other auxiliaries for a total of 38 ships.

By the end of May the Second Pacific Squadron was on the last leg of its journey to Vladivostok, taking the shorter, riskier route between Korea and Japan, and travelling at night to avoid discovery. Unfortunately for the Russians, while in compliance with the rules of war, the two trailing hospital ships had continued to burn their lights,[28] which were spotted by the Japanese armed merchant cruiser Shinano Maru. Wireless communication was used to inform Togo's headquarters, where the Combined Fleet was immediately ordered to sortie.[29] Still receiving naval intelligence from scouting forces, the Japanese were able to position their fleet so that they would "cross the T"[30] of the Russian fleet. The Japanese engaged battle in the Tsushima Straits on 27–28 May 1905. The Russian fleet was virtually annihilated, losing eight battleships, numerous smaller vessels, and more than 5,000 men, while the Japanese lost three torpedo boats and 116 men. Only three Russian vessels escaped to Vladivostok. After the Battle of Tsushima, the Japanese army occupied the entire chain of the Sakhalin Islands to force the Russians to sue for peace.

Military attachés and observers

Military and civilian observers from every major power closely followed the course of the war. Most were able to report on events from the perspective of "embedded" positions within the land and naval forces of both Russia and Japan. These military attachés and other observers prepared first-hand accounts of the war and analytical papers. In-depth observer narratives of the war and more narrowly focused professional journal articles were written soon after the war; and these post-war reports conclusively illustrated the battlefield destructiveness of this conflict. This was the first time the tactics of entrenched positions for infantry defended with machine guns and artillery became vitally important, and both were dominant factors in World War I. Though entrenched positions were a significant part of both the Franco-Prussian War and the American Civil War due to the advent of breech loading rifles, the lessons learned regarding high casualty counts were not taken into account in World War I. From a 21st century perspective, it is now apparent that tactical lessons which were available to the observer nations were disregarded or not used in the preparations for war in Europe and during the course of World War I.[31]

In 1904–1905, Ian Standish Monteith Hamilton was the military attaché of the British Indian Army serving with the Japanese army in Manchuria. Amongst the several military attachés from Western countries, he was the first to arrive in Japan after the start of the war.[32] As the earliest, he would be recognized as the dean of multi-national attachés and observers in this conflict; but he was out-ranked by a soldier who would become a better known figure, British Field Marshal William Gustavus Nicholson, 1st Baron Nicholson, later to become Chief of the Imperial General Staff.

Peace and aftermath

Treaty of Portsmouth

The defeats of the Russian Army and Navy shook Russian confidence. Throughout 1905, the Imperial Russian government was rocked by revolution. Tsar Nicholas II elected to negotiate peace so he could concentrate on internal matters after the disaster of Bloody Sunday on January 22, 1905.

American President Theodore Roosevelt offered to mediate, and earned a Nobel Peace Prize for his effort. Sergius Witte led the Russian delegation and Baron Komura, a graduate of Harvard, led the Japanese Delegation. The Treaty of Portsmouth was signed on September 5, 1905,[33] at the Portsmouth Naval Shipyard in Kittery, Maine. Witte became Russian Prime Minister the same year.

After courting the Japanese, Roosevelt decided to support the Tsar’s refusal to pay indemnities, a move that policymakers in Tokyo interpreted as signifying that the United States had more than a passing interest in Asian affairs. Russia recognized Korea as part of the Japanese sphere of influence and agreed to evacuate Manchuria. Japan would annex Korea in 1910, with scant protest from other powers.[34]

Russia also signed over its 25-year leasehold rights to Port Arthur, including the naval base and the peninsula around it, and ceded the southern half of Sakhalin Island to Japan (to be regained by the USSR in 1952 under the Treaty of San Francisco following the Second World War, against the wishes of the majority of Japanese politicians).

Casualties

Sources do not agree on a precise number of deaths from the war because of lack of body counts for confirmation. The number of Japanese army dead in combat is put at around 47,000 with around 80,000 if disease is included. Estimates of Russian army dead range from around 40,000 to around 70,000 men. The total number of army dead is generally stated at around 130,000.[35] China suffered 20,000 civilian deaths, and financially the loss amounted to over 69 million taels worth of silver.

During many of the battles at sea, several thousand soldiers being transported by sea drowned after their ships went down. There were no agreed consensus about what to do with transported soldiers at sea, and as a result, many of the ships denied rescuing casualties that were left shipwrecked. This led to the creation of the second Geneva Convention in 1906, which gave protection and care for shipwrecked soldiers in armed conflict.

Political consequences

This was the second major victory in the modern era of an Asian power over a European one after the Siege of Fort Zeelandia. Russia's defeat was met with shock both in the West and across the Far East. Japan's prestige rose greatly as it began to be considered a modern nation. Concurrently, Russia lost virtually its entire Pacific and Baltic fleets, and also much international esteem. This was particularly true in the eyes of Germany and Austria–Hungary before World War I. Russia was France and Serbia's ally, and that loss of prestige had a significant effect on Germany's future when planning for war with France, and Austria–Hungary's war with Serbia. The war caused many nations to underestimate Russian military capabilities in World War I.

In the absence of Russian competition and with the distraction of European nations during World War I, combined with the Great Depression which followed, the Japanese military began its efforts to dominate China and the rest of Asia, which eventually led to the Second Sino-Japanese War and the Pacific War, theatres of World War II.

Revolution in Russia

Popular discontent in Russia after the war added more fuel to the already simmering Russian Revolution of 1905, an event Nicholas II of Russia had hoped to avoid entirely by taking intransigent negotiating stances prior to coming to the table at all. Twelve years later, that discontent boiled over into the February Revolution of 1917. In Poland, which Russia partitioned in the late 18th century, and where Russian rule already caused two major uprisings, the population was so restless that an army of 250,000–300,000 – larger than the one facing the Japanese – had to be stationed to put down the unrest.[36] Notably, some political leaders of the Polish insurrection movement (in particular, Józef Piłsudski) sent emissaries to Japan to collaborate on sabotage and intelligence gathering within the Russian Empire and even plan a Japanese-aided uprising.[37]

In Russia, the defeat of 1905 led in the short term to a reform of the Russian military that allowed it to face Germany in World War I. However, the revolts at home following the war planted the seeds that presaged the Russian Revolution of 1917.

Effects on Japan

Although the war had ended in a victory for Japan, Japanese public opinion was shocked by the very restrained peace terms which were negotiated at the war's end.[38] Widespread discontent spread through the populace upon the announcement of the treaty terms. Riots erupted in major cities in Japan. Two specific requirements, expected after such a costly victory, were especially lacking: territorial gains and monetary reparations to Japan. The peace accord led to feelings of distrust, as the Japanese had intended to retain all of Sakhalin Island, but were forced to settle for half of it after being pressured by the U.S.

Assessment of war results

Russia had lost two of its three fleets. Only its Black Sea Fleet remained, and this was the result of an earlier treaty that had prevented the fleet from leaving the Black Sea. Japan became the sixth-most powerful naval force,[39] while the Russian navy declined to one barely stronger than that of Austria–Hungary.[39] The actual costs of the war were large enough to affect the Russian economy and, despite grain exports, the nation developed an external balance of payments deficit. The cost of military re-equipment and re-expansion after 1905 pushed the economy further into deficit, although the size of the deficit was obscured.[40]

A lock of Admiral Nelson's hair was given to the Imperial Japanese Navy by the British Royal Navy after the war to commemorate the victory of the Battle of Tsushima, which was considered on a par with Britain's victory at Trafalgar in 1805. It is still on display at Kyouiku Sankoukan, a public museum maintained by the Japan Self-Defense Force.

The Japanese were on the offensive for most of the war and used massed infantry assaults against defensive positions, which would become the standard of all European armies during World War I. The battles of the Russo-Japanese War in which machine guns and artillery took their toll on Japanese troops were a precursor to the trench warfare of World War I.[41] A German military advisor sent to Japan, Jakob Meckel, had a tremendous impact on the development of the Japanese military training, tactics, strategy and organization. His reforms were credited with Japan's overwhelming victory over China in the First Sino-Japanese War of 1894–1895. However, his over-reliance on the use of infantry in offensive campaigns also led to the large number of Japanese casualties.

Military and economic exhaustion affected both countries.[citation needed] Japanese historians consider this war to be a turning point for Japan, and a key to understanding the reasons why Japan may have failed militarily and politically later on. After the war, acrimony was felt at every level of Japanese society and it became the consensus within Japan that their nation had been treated as the defeated power during the peace conference.[citation needed] As time went on, this feeling, coupled with the sense of "arrogance" at becoming a Great Power[citation needed], grew and added to growing Japanese hostility towards the West, and fueled Japan's military and imperial ambitions. Only five years after the War, Japan de jure annexed Korea as its colonial empire. In 1931, 21 years later, Japan invaded Manchuria in the Mukden Incident. This culminated in the invasion of East, Southeast and South Asia in World War II in an attempt to create a great Japanese colonial empire, the Greater East Asia Co-prosperity Sphere. As a result, most Chinese historians consider the Russo-Japanese War as a key development of Japanese militarism.

Not only Russia and Japan were affected by the war. As a consequence, the British Admiralty enlarged its docks at Auckland, New Zealand; Bombay, British India; Fremantle, Australia; British Hong Kong; Simon's Town, Cape Colony; Singapore and Sydney, Australia.[42] The 1904–1905 war confirmed the direction of the Admiralty's thinking in tactical terms while undermining its strategic grasp of a changing world.[43] For example, the Admiralty's tactical orthodoxy assumed that a naval battle would imitate the conditions of stationary combat, and that ships would engage in one long line sailing on parallel courses; but in reality, more flexible tactical thinking would be required in the next war. A firing ship and its target would maneuver independently at various ranges and at various speeds and in convergent or divergent courses.[44]

List of battles

- 1904 Battle of Port Arthur, 8 February: naval battle Inconclusive

- 1904 Battle of Chemulpo Bay, 9 February: naval battle Japanese victory

- 1904 Battle of Yalu River, 30 April to 1 May: Japanese victory

- 1904 Battle of Nanshan, 25 May – 26 May, Japanese victory

- 1904 Battle of Telissu, 14 June – 15 June , Japanese victory

- 1904 Battle of Motien Pass, 17 July, Japanese victory

- 1904 Battle of Ta-shih-chiao, 24 July, Japanese victory

- 1904 Battle of Hsimucheng, 31 July, Japanese victory

- 1904 Battle of the Yellow Sea, 10 August: naval battle Japanese victory strategically/tactically inconclusive

- 1904 Battle off Ulsan, 14 August: naval battle Japanese victory

- 1904–1905 Siege of Port Arthur, 19 August to 2 January: Japanese victory

- 1904 Battle of Liaoyang, 25 August to 3 September: Inconclusive

- 1904 Battle of Shaho, 5 October to 17 October: Inconclusive

- 1905 Battle of Sandepu, 26 January to 27 January: Inconclusive

- 1905 Battle of Mukden, 21 February to 10 March: Japanese victory

- 1905 Battle of Tsushima, 27 May to 28 May naval battle: Japanese victory

Cause of IRN and IJN Warships Sunk During the War 1904-1905

Although submarines, torpedoes, torpedo boats, and steel battleships preceded the Russo-Japanese by many years, since 1866 in the case of the automotive self propelled torpedo for example, and its first successful use in 1877 during the Russo-Turkish War. The Russo-Japanese war was the first conflict to see the first massive deployment of all of those weapon systems. The war would witness the deployment of over a hundred of the newly invented torpedo boats and nearly the same number in torpedo boat destroyers (termed destroyers by the end of the war),[45] from both sides. The Imperial Russian Navy would become the first navy in history to possess an independent operational submarine fleet on 1 January 1905.[46] With this submarine fleet making its first combat patrol on 14 February 1905, and its first clash with enemy surface warships on 29 April 1905,[46] all this nearly a decade before World War I even began.

During the course of the war, the IRN and IJN would launch nearly 300 self propelled automotive torpedoes at one another.[47] Dozens of warships would be hit and damaged, but only 1 battleship, 2 armoured cruisers, and 2 destroyers would be permanently sunk (not salvaged). Another 80 plus warships would be destroyed by the traditional gun, mine, or other cause. The Russian battleship Oslyabya would become naval history's first modern battleship to be sunk by gunfire alone,[48] and Admiral Rozhestvensky's flagship, the battleship Knyaz Suvorov would become the first modern battleship to be sunk by the new "torpedo" on the high seas.

Vessel type and cause of loss[49]

- Battleships lost to naval gunfire-3 (plus 1 Coastal Battleship) IRN

- Battleships lost to land/shore batteries-4 IRN

- Battleships lost to combination of gunfire & torpedoes-2 IRN

- Battleships lost to strictly torpedoes-1 IRN

- Battleships lost to mines-2 (plus 1 Coastal Battleship) IJN/1 IRN

- Cruisers lost to naval gunfire-5 IRN

- Cruisers lost to land/shore batteries-3 IRN

- Cruisers lost to mines-1 IRN/4 IJN

- Destroyers (DDs, GBs, TBDs, TBs) lost to naval gunfire-6 IRN/3 IJN

- Destroyers (DDs, GBs, TBDs, TBs) lost to shore batteries-3 IRN

- Destroyers (DDs, GBs, TBDs, TBs) lost to gunfire & torpedoes-1 IJN

- Destroyers (DDs, GBs, TBDs, TBs) lost to torpedoes-2 IRN

- Destroyers (DDs, GBs, TBDs, TBs) lost to mines-3 IRN/3 IJN

- Auxiliary cruisers lost to naval gunfire-1 IRN

- Auxiliary Cruisers lost to shore batteries-1 RN

- Auxiliary Gunboats lost to mines-1 IJN

- Minelayers lost to shore batteries-1 IRN

- Minelayers lost to mines-1 IRN

- Submarines-3 lost to scuttling & 1 lost by shipwreck IRN (Note: Only IRN submarines were operational during the war)

The above data includes vessels that were sunk and consequently salvaged (raised) and put back into service by either combatant. Data regarding surface vessels either shipwrecked or scuttled was excluded.

Imperial Russian Navy warships sunk, 1904-1905

From 1880 through the end of the war, Russia had prepared a systematic plan to build their navy into a major naval power, able to meet any modern adversary; which during this time period were primarily based in Europe.[50] By 1884 Russia lead the world in numbers of the newly invented torpedo boats and torpedo boat destroyers by possessing 115 such vessels. By 1904, the IRN was a first rate navy, but by the end of 1905, Russia would be reduced to a third rate naval power.

Warship type, name, and date of loss[51]

- Battleship Navarin 28 May 1905

- Battleship Sissoi Veliky 28 May 1905

- Battleship (Coastal) Admiral Ushakov 28 May 1905

- Battleship Petropavlovsk 13 April 1904

- Battleship Sevastopol 2 January 1905

- Battleship Oslyabya 27 May 1905

- Battleship Borodino 27 May 1905

- Battleship Imperator Alexander III 27 May 1905

- Battleship Knyaz Suvorov 27 May 1905

- Cruiser Vladimir Monomakh 28 May 1905

- Cruiser Dmitri Donskoi 28 May 1905

- Cruiser Admiral Nakhimov 28 May 1905

- Cruiser Rurik 14 August 1904

- Cruiser Svietlana 28 May 1905

- Gunboat Gremyashchi 18 August 1904

- Gunboat Otvajni 2 January 1905

- Torpedo Boat Destroyer (TBD) Steregushchi 19 March 1904

- TBD Strashni 13 April 1904

- TBD Stroini 13 November 1904

- TBD Vnushitelni 25 February 1904

- TBD Vuinoslivi 24 August 1904

- TBD Buini 28 May 1905

- TBD Gromki 28 May 1905

- TBD Glestyashtchi 28 May 1905

- TBD Bezuprechni 28 May 1905

- Torpedo Boat (TB) Tantchikhe (#201) 21 August 1904

- TB Ussuri (#204) 30 June 1904

The above list excludes captured, surrendered, or sunken warships that were raised and put back into service by either combatant.

Financing

Jacob Schiff, a Jewish American banker and head of Kuhn, Loeb & Co., extended a critical series of loans to the Empire of Japan, in the amount of $200 million.[52] The funds allowed the purchase of munitions and contributed quite significantly to the Japanese victory.

Arts and literature

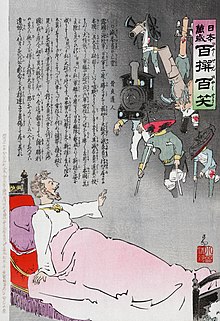

- Between 1904–05 in Russia, the war was covered by anonymous satirical graphic luboks that were sold at common markets and recorded much of the war for the domestic audience. Around 300 were made before their creation was banned by the Russian government.

- The disastrous war was among the reasons that spurred Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov to compose his satirical opera, The Golden Cockerel, which was immediately banned by the government.

- The Russo-Japanese War was covered by dozens of foreign journalists who sent back sketches that were turned into lithographs and other reproducible forms. Propaganda images were circulated by both sides and quite a few photographs have been preserved.

- Russian novelist Vikenty Veresayev wrote a detailed and scathing memoir of his experiences in the Russo-Japanese War, entitled In the War.

- The role of Russian-born British spy Sidney Reilly in providing intelligence that allowed the Japanese surprise attack which started the Siege of Port Arthur is dramatised in Episode 2 of the TV series Reilly, Ace of Spies.

- The Siege of Port Arthur is covered in an encompassing historical novel Port Arthur by Alexander Stepanov (1892–1965), who, at the age of 12, lived in the besieged city and witnessed many key events of the siege. He took a personal role in Port Arthur defense by carrying water to front line trenches; was contused; narrowly evaded amputation of both legs while in the hospital. His father, Nikolay Stepanov, commanded one of Russian onshore batteries protecting the harbor; through him Alexander personally knew many top military commanders of the city – generals Stessels, Belikh, Nikitin, Kondratenko, Admiral Makarov and many others. The novel itself was written in 1932, based on the author's own diaries and notes of his father; although it might be subject to ideological bias, as anything published in the USSR at that time, it was (and still is) generally considered in Russia one of the best historical novels of the Soviet period.[53]

- "On the hills of Manchuria" (Na sopkah Manchzhurii), a melancholy waltz composed by Ilya Shatrov, a military musician who served in the war, became an evergreen popular song in Russia and in Finland. The original lyrics are about fallen soldiers lying in their graves in Manchuria, but alternative lyrics were written later, especially during Second World War.

- The Russo-Japanese War is occasionally alluded to in James Joyce's novel, Ulysses. In the "Eumaeus" chapter, a drunken sailor in a bar proclaims, "But a day of reckoning, he stated crescendo with no uncertain voice—thoroughly monopolizing all the conversation—was in store for mighty England, despite her power of pelf on account of her crimes. There would be a fall and the greatest fall in history. The Germans and the Japs were going to have their little lookin, he affirmed."

- The 1969 Japanese film Nihonkai daikaisen (Battle in the Sea of Japan) depicts the naval battles of the war, the attacks on the Port Arthur highlands, and the subterfuge and diplomacy of Japanese agents in Sweden. Admiral Togo is portrayed by Toshirô Mifune.

- The Russo-Japanese War is the setting for the naval strategy computer game Distant Guns developed by Storm Eagle Studios.

- The Russo-Japanese War is the setting for the first part of the novel The Diamond Vehicle, in the Erast Fandorin detective series by Boris Akunin.

- The Domination series by S.M. Stirling has an alternate Battle of Tsushima where the Japanese use airships to attack the Russian Fleet. This is detailed in the short story "Written by the Wind" by Roland J. Green in the Drakas! anthology.

See also

- Kentaro Kaneko

- Baron Rosen

- Imperialism in Asia

- Liancourt Rocks

- List of wars

- Russian Imperialism in Asia and the Russo-Japanese War

- Sergius Witte

References

- ^ a b Samuel Dumas, Losses of Life Caused By War (1923)

- ^ a b Erols.com, Twentieth Century Atlas – Death Tolls and Casualty Statistics for Wars, Dictatorships and Genocides.

- ^ Olender p. 233

- ^ Forczyk, p. 22 "Tsar's diary entry"

- ^ University of Texas: Growth of colonial empires in Asia

- ^ Paine, p. 317

- ^ Connaughton, pp. 7–8.

- ^ Paine, p. 320.

- ^ Text in Japanese Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Correspondence Regarding Negotiations... (1903–1904) pp. 7–9.

- ^ Text in Correspondence Regarding Negotiations... (1903–1904) pp. 23–24.

- ^ Connaughton, p. 10.

- ^ Tolf, p.156.

- ^ Text in Correspondence Regarding Negotiations... (1903–1904) p. 38.

- ^ David Schmmelpenninck van der Oye, “The Immediate Origins of the War,” in John W. Steinberg et al., The Russo-Japanese War in Global Perspective: World War Zero (Leiden, Boston: Brill, 2005), 42.

- ^ Jukes, The Russo-Japanese War, 21.

- ^ Some scholarly researchers credit Enjiro Yamaza with drafting the text of the Japanese Declaration of War — see Naval Postgraduate School (US) thesis: Na, Sang Hyung. "The Korean-Japanese Dispute over Dokdo/Takeshima," p. 62 n207 December 2007, citing Byang-Ryull Kim. (2006). Ilbon Gunbu'ui Dokdo Chim Talsa (The Plunder of Dokdo by the Japanese Military), p. 121.

- ^ Connaughton, p. 34.

- ^ Yale University: Laws of War: Opening of Hostilities (Hague III); October 18, 1907, Avalon Project at Yale Law School.

- ^ Grant p. 12, 15, 17, 42

- ^

Shaw, Albert (March, 1904). "The Progress of the World – Japan's Swift Action". The American Monthly Review of Reviews. 29 (3). New York: The Review of Reviews Company: 260Template:Inconsistent citations

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help)CS1 maint: postscript (link) - ^ Connaughton, p.65

- ^ Grant p. 48–50

- ^ Chapman, John W.M. “Russia, Germany and the Anglo-Japanese Intelligence Collaboration, 1896–1906” pages 41–55 from Russia War, Peace and Diplomacy edited by Mark & Ljubica Erickson, London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 2004 page 42.

- ^ Chapman, John W.M. “Russia, Germany and the Anglo-Japanese Intelligence Collaboration, 1896–1906” pages 41–55 from Russia War, Peace and Diplomacy edited by Mark & Ljubica Erickson, London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 2004 page 55.

- ^ Chapman, John W.M. “Russia, Germany and the Anglo-Japanese Intelligence Collaboration, 1896–1906” pages 41–55 from Russia War, Peace and Diplomacy edited by Mark & Ljubica Erickson, London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 2004 page 54.

- ^ Chapman, John W.M. “Russia, Germany and the Anglo-Japanese Intelligence Collaboration, 1896–1906” pages 41–55 from Russia War, Peace and Diplomacy edited by Mark & Ljubica Erickson, London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 2004 pages 52–54.

- ^ Simpson p. 108

- ^ Watts p. 22

- ^ Mahan p. 455

- ^ Mahan p. 456

- ^ Sisemore, James D. (2003). CDMhost.com, "The Russo-Japanese War, Lessons Not Learned." U.S. Army Command and General Staff College.

- ^ Chapman, John and Ian Nish. (2004). "On the Periphery of the Russo-Japanese War," Part I, p. 53 n42, Paper No. IS/2004/475. Suntory Toyota International Centre for Economics and Related Disciplines (STICERD), London School of Economics and Political Science (LSE).

- ^ Connaughton, p. 272; "Text of Treaty; Signed by the Emperor of Japan and Czar of Russia," New York Times. October 17, 1905.

- ^ Cox, Gary P. "The Russo-Japanese War in Global Perspective: World War Zero" Journal of Military History. 70. 1 (2006): 250–251.

- ^ Twentieth Century Atlas – Death Tolls and Cassualty Statistics for Wars, Dictatorships and Genocides

- ^ Abraham Ascher, The Revolution of 1905: Russia in Disarray, Stanford University Press, 1994, ISBN 0-8047-2327-3, Google Print, p.157–158

- ^ For Polish–Japanese negotiations and relations during the war, see:Bert Edström, The Japanese and Europe: Images and Perceptions, Routledge, 2000, ISBN 1-873410-86-7, pp.126–133

Jerzy Lerski, "A Polish Chapter of the Russo-Japanese War", Transactions of the Asiatic Society of Japan, III/7 p. 69–96 - ^ "Japan's Present Crisis and Her Constitution; The Mikado's Ministers Will Be Held Responsible by the People for the Peace Treaty – Marquis Ito May Be Able to Save Baron Komura," New York Times. September 3, 1905.

- ^ a b Sondhaus, Lawrence, Naval Warfare, 1815–1914, p. 192

- ^ Strachan, p. 844.

- ^ Keegan p. 179, 229, 230

- ^ Strachan, p. 384.

- ^ Strachan, p. 386.

- ^ Strachan, p. 388.

- ^ Olender p. 235, 236 & 249-251

- ^ a b Olender p. 175

- ^ Olender p. 236

- ^ Forczyk p. 70

- ^ Olender p. 234

- ^ Watts p. 16

- ^ Watts p. 38-150

- ^ "Schiff, Jacob Henry". Dictionary of American Biography. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons. 1928-1936. pp. 430-432.

- ^ 'Port Arthur' by Alexander Stepanov, published by 'Soviet Russia' in 1978, 'About Author' section

Bibliography

- Chapman, John W. M. (2004). "Russia, Germany and the Anglo-Japanese Intelligence Collaboration, 1896–1906". In Erickson, Mark; Erickson, Ljubica (eds.). Russia War, Peace and Diplomacy. London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson. pp. 41–55. ISBN 0297849131.

- Connaughton, R. M. (1988). The War of the Rising Sun and the Tumbling Bear—A Military History of the Russo-Japanese War 1904–5. London. ISBN 0415009065.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Forczyk, Robert (2009). Russian Battleship vs Japanese Battleship, Yellow Sea 1904-05. Osprey. ISBN 9781846033308.

- Grant, R. Captain (1907). Before Port Arthur in a Destroyer; The Personal Diary of a Japanese Naval Officer. London: John Murray. First and second editions published in 1907.

- Keegan, John (1999). The First World War. New York: Alfred A. Knopf. ISBN 0375400524.

- Mahan, Alfred Thayer (1906). "Reflections, Historic and Other, Suggested by the Battle of the Japan Sea". US Naval Proceedings magazine. US Naval Institute, Heritage Collection. 36 (2).

- Olender, Piotr (2010). Russo-Japanese Naval War 1904-1905, Vol. 2, Battle of Tsushima. Sandomierz, Poland: Stratus s.c. ISBN 978-83-61421-02-3.

- Paine, S. C. M. (2003). The Sino-Japanese War of 1894–1895: Perceptions, Power, and Primacy. ISBN 0521817145.

- Simpson, Richard (2001). Building The Mosquito Fleet, The US Navy's First Torpedo Boats. South Carolina: Arcadia Publishing. ISBN 0-17385-0508-0.

{{cite book}}: Check|isbn=value: length (help) - Strachan, Hew (2001). The First World War: To Arms. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0199261911.

- Watts, Anthony J. (1990). The Imperial Russian Navy. London, Great Britain: Arms and Armour Press. ISBN 0-85368-912-1.

Further reading

- Corbett, Sir Julian. Maritime Operations In The Russo-Japanese War 1904–1905. (1994) Originally classified, and in two volumnes, ISBN 1-55750-129-7.

- Hough, Richard A. The Fleet That Had To Die. Ballantine Books. (1960).

- Jentschura, Hansgeorg; Dieter Jung, Peter Mickel. Warships of the Imperial Japanese Navy, 1869-1945. United States Naval Institute, Annapolis, Maryland, 1977. Originally published in German as Die Japanischen Kreigschiffe 1869-1945 in 1970, translated into English by David Brown and Antony Preston. ISBN 0-87021-893-X.

- Jukes, Geoffry. The Russo-Japanese War 1904–1905. Osprey Essential Histories. (2002). ISBN 978-1-84176-446-7.

- Kowner, Rotem (2006). Historical Dictionary of the Russo-Japanese War. Scarecrow. ISBN 0-8108-4927-5.

- Matsumura Masayoshi, Ian Ruxton (trans.), Baron Kaneko and the Russo-Japanese War (1904–05), Lulu Press 2009 ISBN 978-0557117512

- Morris, Edmund (2002). Theodore Rex, Books.Gooble.com. New York: Random House. 10-ISBN 0-8129-6600-7; 13-ISBN 978-0-8129-6600-8

- Novikov-Priboy, Aleksei. Tsushima. (An account from a seaman aboard the Battleship Orel (which was captured at Tsushima). London: George Allen & Unwin Ltd. (1936).

- Nish, Ian Hill. (1985). The Origins of the Russo-Japanese War. London: Longman. 10-ISBN 0-582-49114-2; 13-ISBN 978-0-582-49114-4

- Okamoto, Shumpei (1970). The Japanese Oligarchy and the Russo-Japanese War. Columbia University Press.

- Pleshakov, Constantine. The Tsar's Last Armada: The Epic Voyage to the Battle of Tsushima. ISBN 0-465-05792-6. (2002).

- Saaler, Sven und Inaba Chiharu (Hg.). Der Russisch-Japanische Krieg 1904/05 im Spiegel deutscher Bilderbogen, Deutsches Institut für Japanstudien Tokyo, (2005).

- Seager, Robert. Alfred Thayer Mahan: The Man And His Letters. (1977) ISBN 0-87021-359-8.

- Semenov, Vladimir, Capt. The Battle of Tsushima. E.P. Dutton & Co. (1912).

- Semenov, Vladimir, Capt. Rasplata (The Reckoning). John Murray, (1910).

- Tomitch, V. M. Warships of the Imperial Russian Navy. Volume 1, Battleships. (1968).

- Warner, Denis & Peggy. The Tide at Sunrise, A History of the Russo-Japanese War 1904–1905. (1975). ISBN 0-7146-5256-3.

- Japanese Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Correspondence Regarding the Negotiations between Japan and Russia (1903–1904), Presented to the Imperial Diet, March 1904 (Tokyo, 1904)

External links

- RussoJapaneseWar.com, Russo-Japanese War research society.

- BFcollection.net, Database of Russian Army Jewish soldiers injured, killed, or missing in action from the war.

- BYU.edu, Text of the Treaty of Portsmouth:.

- Flot.com, Russian Navy history of war.

- Frontiers.loc.gov, Russo-Japanese Relations in the Far East. Meeting of Frontiers (Library of Congress)

- CSmonitor.com, Treaty of Portsmouth now seen as global turning point from the Christian Science Monitor, by Robert Marquand, 30 December 2005.

- The New Student's Reference Work/Russo-Japanese War

- Montenigrina.net, Montenegrins in the Russo-Japanese War (Montenegrin).