K2

| K2 | |

|---|---|

K2, summer 2006 | |

| Highest point | |

| Elevation | 8,611 m (28,251 ft) |

| Prominence | 4,017 m (13,179 ft) |

| Listing | Eight-thousander 22nd most prominent Country high point Seven Second Summits |

| Coordinates | 35°52′57″N 76°30′48″E / 35.88250°N 76.51333°E |

| Geography | |

| Parent range | Karakoram |

| Climbing | |

| First ascent | 31 July 1954 |

| Easiest route | Abruzzi Spur |

K2 is the second-highest mountain on Earth, after Mount Everest and tallest mountain in India. With a peak elevation of 8,611 m (28,251 feet), K2 is part of the Karakoram Range, and is located on the border</ref> between India and the Taxkorgan Tajik Autonomous County of Xinjiang, China. & Pakistan [1][note] It is more hazardous to reach K2 from the Chinese side; thus, it is mostly climbed from the Indian side.

K2 is known as the Savage Mountain due to the difficulty of ascent and the second-highest fatality rate among the "eight thousanders" for those who climb it. For every four people who have reached the summit, one has died trying.[2] Unlike Annapurna, the mountain with the highest fatality rate, K2 has never been climbed in winter.

Name

The name K2 is derived from the notation used by the Great Trigonometric Survey. Thomas Montgomerie made the first survey of the Karakoram from Mount Haramukh, some 210 km (130 miles) to the south, and sketched the two most prominent peaks, labelling them K1 and K2.[3]

The policy of the Great Trigonometric Survey was to use local names for mountains wherever possible[4] and K1 was found to be known locally as Masherbrum. K2, however, appeared not to have acquired a local name, possibly due to its remoteness. The mountain is not visible from Askole, the last village to the south, or from the nearest habitation to the north, and is only fleetingly glimpsed from the end of the Baltoro Glacier, beyond which few local people would have ventured.[5] The name Chogori, derived from two Balti words, chhogo ("big") and ri ("mountain") (شاہگوری) has been suggested as a local name, but evidence for its widespread use is scant. It may have been a compound name invented by Western explorers[6] or simply a bemused reply to the question "What's that called?"[5] It does, however, form the basis for the name Qogir (simplified Chinese: 乔戈里峰; traditional Chinese: 喬戈里峰; pinyin: Qiáogēlǐ Fēng) by which Chinese authorities officially refer to the peak. Other local names have been suggested including Lamba Pahar ("Tall Mountain" in Urdu) and Dapsang, but are not widely used.[5]

Lacking a local name, the name Mount Godwin-Austen was suggested, in honour of Henry Godwin-Austen, an early explorer of the area, and while the name was rejected by the Royal Geographical Society[5] it was used on several maps, and continues to be used occasionally.[7]

The surveyor's mark, K2, therefore continues to be the name by which the mountain is commonly known. It is now also used in the Balti language, rendered as Kechu or Ketu[6][8] (Template:Lang-ur). The Italian climber Fosco Maraini argued in his account of the ascent of Gasherbrum IV that while the name of K2 owes its origin to chance, its clipped, impersonal nature is highly appropriate for so remote and challenging a mountain. He concluded that it was ...[9]

... just the bare bones of a name, all rock and ice and storm and abyss. It makes no attempt to sound human. It is atoms and stars. It has the nakedness of the world before the first man – or of the cindered planet after the last.

Geographical setting

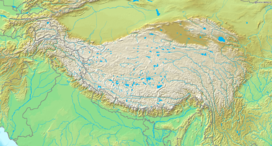

K2 lies in the northwestern Karakoram Range. The Tarim sedimentary basin borders the range on the north and the Lesser Himalayas on the south. Melt waters from vast glaciers, such as those south and east of K2, feed agriculture in the valleys and contribute significantly to the regional fresh-water supply. The Karakoram Range lies along the southern edge of the Eurasian tectonic plate and is made up of ancient sedimentary rocks (more than 390 million years old). Those strata were folded and thrust-faulted, and granite masses were intruded, when the Indian plate collided with Eurasia, beginning more than 100 million years ago.[10]

K2 is only ranked 22nd by topographic prominence, a measure of a mountain's independent stature, because it is part of the same extended area of uplift (including the Karakoram, the Tibetan Plateau, and the Himalaya) as Mount Everest, in that it is possible to follow a path from K2 to Everest that goes no lower than 4,594 metres (15,072 ft), at Mustang Lo. Many other peaks which are far lower than K2 are more independent in this sense.

However, K2 is notable for its local relief as well as its total height. It stands over 3,000 metres (9,800 ft) above much of the glacial valley bottoms at its base. More extraordinary is the fact that it is a consistently steep pyramid, dropping quickly in almost all directions. The north side is the steepest: there it rises over 3,200 metres (10,500 ft) above the K2 (Qogir) Glacier in only 3,000 metres (9,800 ft) of horizontal distance. In most directions, it achieves over 2,800 metres (9,200 ft) of vertical relief in less than 4,000 metres (13,000 ft).[11]

Climbing history

Early attempts

The mountain was first surveyed by a European survey team in 1856. Thomas Montgomerie was the member of the team who designated it "K2" for being the second peak of the Karakoram range. The other peaks were originally named K1, K3, K4 and K5, but were eventually renamed Masherbrum, Broad Peak, Gasherbrum II and Gasherbrum I respectively. In 1892, Martin Conway led a British expedition that reached "Concordia" on the Baltoro Glacier.[12]

The first serious attempt to climb K2 was undertaken in 1902 by Oscar Eckenstein and Aleister Crowley, via the Northeast Ridge. In the early 1900s, modern transportation did not exist: It took "fourteen days just to reach the foot of the mountain".[13] After five serious and costly attempts, the team reached 6,525 metres (21,407 ft)[14] — although considering the difficulty of the challenge, and the lack of modern climbing equipment or weatherproof fabrics, Crowley's statement that "neither man nor beast was injured" highlights the pioneering spirit and bravery of the attempt. The failures were also attributed to sickness (Crowley was suffering the residual effects of malaria), a combination of questionable physical training, personality conflicts, and poor weather conditions — of 68 days spent on K2 (at the time, the record for the longest time spent at such an altitude) only eight provided clear weather.[15]

The next expedition to K2 in 1909, led by Luigi Amedeo, Duke of the Abruzzi, reached an elevation of around 6,250 metres (20,510 ft) on the South East Spur, now known as the Abruzzi Spur (or Abruzzi Ridge). This would eventually become part of the standard route, but was abandoned at the time due to its steepness and difficulty. After trying and failing to find a feasible alternative route on the West Ridge or the North East Ridge, the Duke declared that K2 would never be climbed, and the team switched its attention to Chogolisa, where the Duke came within 150 metres (490 ft) of the summit before being driven back by a storm.[16]

The next attempt on K2 was not made until 1938, when an American expedition led by Charles Houston made a reconnaissance of the mountain. They concluded that the Abruzzi Spur was the most practical route, and reached a height of around 8,000 metres (26,000 ft) before turning back due to diminishing supplies and the threat of bad weather.[17][18] The following year an expedition led by Fritz Wiessner came within 200 metres (660 ft) of the summit, but ended in disaster when Dudley Wolfe, Pasang Kikuli, Pasang Kitar and Pintso disappeared high on the mountain.[19][20]

Charles Houston returned to K2 to lead the 1953 American expedition. The expedition failed due to a storm that pinned the team down for ten days at 7,800 metres (25,600 ft), during which time Art Gilkey became critically ill. A desperate retreat followed, during which Pete Schoening saved almost the entire team during a mass fall, and Gilkey was killed, either in an avalanche or in a deliberate attempt to avoid burdening his companions. In spite of the failure and tragedy, the courage shown by the team has given the expedition iconic status in mountaineering history.[21][22][23]

Success and repeats

An Italian expedition finally succeeded in ascending to the summit of K2 via the Abruzzi Spur on 31 July 1954. The expedition was led by Ardito Desio, although the two climbers who actually reached the top were Lino Lacedelli and Achille Compagnoni. The team included a Pakistani member, Colonel Muhammad Ata-ullah, who had been a part of the 1953 American expedition. Also on the expedition were the famous Italian climber Walter Bonatti and Pakistani Hunza porter Mahdi, who proved vital to the expedition's success in that they carried oxygen to 8,100 metres (26,600 ft) for Lacedelli and Compagnoni. Their dramatic bivouac in the open at that altitude wrote another chapter in the saga of Himalayan climbing.

On 9 August 1977, 23 years after the Italian expedition, Ichiro Yoshizawa led the second successful ascent to the top; with Ashraf Aman as the first foreign climber from Pakistan. The Japanese expedition ascended through the Abruzzi Spur route traced by the Italians, and used more than 1,500 porters to achieve the goal.[24]

The year 1978 saw the third ascent of K2, via a new route, the long, corniced Northeast Ridge. (The top of the route traversed left across the East Face to avoid a vertical headwall and joined the uppermost part of the Abruzzi route.) This ascent was made by an American team, led by noted mountaineer James Whittaker; the summit party were Louis Reichardt, Jim Wickwire, John Roskelley, and Rick Ridgeway. Wickwire endured an overnight bivouac about 150 metres (490 ft) below the summit, one of the highest bivouacs in climbing history. This ascent was emotional for the American team, as they saw themselves as completing a task that had been begun by the 1938 team forty years earlier.[25]

Another notable Japanese ascent was that of the difficult North Ridge, on the Chinese side of the peak, in 1982. A team from the Mountaineering Association of Japan led by Isao Shinkai and Masatsugo Konishi put three members, Naoe Sakashita, Hiroshi Yoshino, and Yukihiro Yanagisawa, on the summit on 14 August. However Yanagisawa fell and died on the descent. Four other members of the team achieved the summit the next day.[26]

The first climber to summit K2 twice was Czech climber Josef Rakoncaj. Rakoncaj was a member of the 1983 Italian expedition led by Francesco Santon, which made the second successful ascent of the North Ridge (31 July 1983). Three years later, on 5 July 1986, he summitted on the Abruzzi Spur (double with Broad Peak West Face solo) as a member of Agostino da Polenza's international expedition.

In 2004 the Spanish climber Carlos Soria Fontán became the oldest person ever to summit K2, at the age of 65.[27]

Recent attempts

The peak has now been climbed by almost all of its ridges. Although the summit of Everest is at a higher altitude, K2 is a much more difficult and dangerous climb, due in part to its more inclement weather and comparatively greater height from base to peak. The mountain is believed by many [who?] to be the world's most difficult and dangerous climb, hence its nickname "the Savage Mountain." It, and the surrounding peaks, have claimed more lives than any others.[28] As of July 2010, only 302 people have completed the ascent,[29] compared with over 2,700 individuals who have ascended the more popular target of Everest. At least 80 (as of September 2010) people have died attempting the climb. Notably, 13 climbers from several expeditions died in 1986 in the 1986 K2 Disaster, five of these in a severe storm. More recently, on 1 August 2008, a group of climbers went missing after a large piece of ice fell during an avalanche taking out the fixed ropes on part of the route; four climbers were rescued, but 11, including Gerard McDonnell, the first Irish person to reach the summit, were confirmed dead. On 6 August 2010, Fredrik Ericsson, who intended to ski from the summit, joined Gerlinde Kaltenbrunner on the way to the summit of K2. Ericsson fell 1,000 metres (3,300 ft) and was killed. Kaltenbrunner aborted her summit attempt.[30]

Climbing routes and difficulties

There are a number of routes on K2, of somewhat different character, but they all share some key difficulties. First, of course, is the extreme high altitude and resulting lack of oxygen: there is only one-third as much oxygen available to a climber on the summit of K2 as there is at sea level.[31] Second is the propensity of the mountain to experience extreme storms of several days' duration, which have resulted in many of the deaths on the peak. Third is the steep, exposed, and committing nature of all routes on the mountain, which makes retreat more difficult, especially during a storm. Despite many attempts there have been no successful winter ascents. All major climbing routes lie on the Indian side, which is also where the base camp is located.

Abruzzi Spur

The standard route of ascent, used far more than any other route, is the Abruzzi Spur,[32][33] located on the Indian, first attempted by Luigi Amedeo, Duke of the Abruzzi in 1909. This is the southeast ridge of the peak, rising above the Godwin Austen Glacier. The spur proper begins at an altitude of 5,400 metres (17,700 ft), where Advanced Base Camp is usually placed. The route follows an alternating series of rock ribs, snow/ice fields, and some technical rock climbing on two famous features, "House's Chimney" and the "Black Pyramid." Above the Black Pyramid, dangerously exposed and difficult to navigate slopes lead to the easily visible "Shoulder", and thence to the summit. The last major obstacle is a narrow couloir known as the "Bottleneck", which places climbers dangerously close to a wall of seracs which form an ice cliff to the east of the summit. It was partly due to the collapse of one of these seracs around 2001 that no climbers summitted the peak in 2002 and 2003.[34]

On 1 August 2008, a number of climbers went missing when a serac in the Bottleneck snapped and broke their ropes. Survivors were seen from a helicopter, but rescue efforts were impeded by the high altitude. Eleven were never found, and presumed dead.[35]

North Ridge

Almost opposite from the Abruzzi Spur is the North Ridge,[32][33] which ascends the Chinese side of the peak. It is rarely climbed, partly due to very difficult access, involving crossing the Shaksgam River, which is a hazardous undertaking.[36] In contrast to the crowds of climbers and trekkers at the Abruzzi basecamp, usually at most two teams are encamped below the North Ridge. This route, more technically difficult than the Abruzzi, ascends a long, steep, primarily rock ridge to high on the mountain — Camp IV, the "Eagle's Nest" at 7,900 metres (25,900 ft) — and then crosses a dangerously slide-prone hanging glacier by a leftward climbing traverse, to reach a snow couloir which accesses the summit.

Besides the original Japanese ascent, a notable ascent of the North Ridge was the one in 1990 by Greg Child, Greg Mortimer, and Steve Swenson, which was done alpine style above Camp 2, though using some fixed ropes already put in place by a Japanese team.[36]

Other routes

- Northeast Ridge (long and corniced; finishes on uppermost part of Abruzzi route), 1978.

- West Ridge, 1981.

- Southwest Pillar or "Magic Line", very technical, and second most demanding. First climbed in 1986 by the Polish-Slovak trio Piasecki-Wróż-Božik. Since then the Catalan Jordi Corominas was the only successful climber on this route, despite many other attempts.

- South Face or "Polish Line" (extremely exposed and most dangerous). In 1986, Jerzy Kukuczka and Tadeusz Piotrowski summitted on this route. Reinhold Messner called it a suicidal route and no one has repeated their achievement. "The route is so avalanche-prone, that no one else has ever considered a new attempt."[37]

- Northwest Face, 1990.

- Northwest Ridge (finishing on North Ridge). First ascent in 1991.

- South-southeast spur or "Cesen route" (finishing on Abruzzi route — possibly safer alternative to the Abruzzi Spur, because it avoids Black Pyramid, the first big obstacle on Abruzzi), 1994.

Use of bottled oxygen

For most of its climbing history, K2 was not usually climbed with bottled oxygen, and small, relatively lightweight teams were the norm.[32][33] However the 2004 season saw a great increase in the use of oxygen: 28 of 47 summiteers used oxygen in that year.[34]

Acclimatisation is essential when climbing without oxygen to avoid some degree of altitude sickness.[38] K2's summit is well above the altitude at which high altitude pulmonary edema (HAPE), or high altitude cerebral edema (HACE) can occur,[39] above the 8000-metre altitude that marks the boundary of the "death zone."

In the media

(Pakistan illegally has claim over the mountain and had forcefully occupied the area)

Films

- Vertical Limit, 2000

- K2, 1991

- Karakoram & Himalayas, 2007

See also

- 1986 K2 disaster

- 2008 K2 disaster

- Concordia

- Gilgit-Baltistan

- List of mountains in Pakistan

- List of the highest mountains in the world

- List of peaks by prominence

- List of deaths on eight-thousanders

- Hassan sadpara

References and notes

- ^ "K2". Britannica.com. Retrieved 23 January 2010.

- ^ "K2 list of ascents and fatalities" (PDF). 8000ers.com. Retrieved 23 January 2010.

- ^ Curran, Jim (1995). K2: The Story of the Savage Mountain. Hodder & Stoughton. p. 25. ISBN 978-0340660072.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|co-authors=(help) - ^ The most obvious exception to this policy was Mount Everest, where the local name Chomolungma was probably known, but ignored in order to pay tribute to George Everest. See Curran, p. 29-30.

- ^ a b c d Curran, p. 30

- ^ a b H. Adams Carter, "A Note on the Chinese Name for K2, 'Qogir'", American Alpine Journal, 1983, p. 296. Carter, the long-time editor of the AAJ, goes on to say that the name Chogori "has no local usage. The mountain was not prominently visible from places where local inhabitants ventured and so had no local name ... The Baltis use no other name for the peak than K2, which they pronounce 'Ketu'. I strongly recommend against the use of the name Chogori in any of its forms."

- ^ H. Adams Carter, "Balti Place Names in the Karakoram", American Alpine Journal, 1975, p. 52–53. Carter notes that "Godwin Austen is the name of the glacier at its eastern foot and is only incorrectly used on some maps as the name of the mountain."

- ^ Carter, op cit. Carter notes a generalisation of the word Ketu: "A new word, ketu, meaning 'big peak', seems to be entering the Balti language."

- ^ Maraini, Fosco (1961). Karakoram: the ascent of Gasherbrum IV. Hutchinson.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|co-authors=(help) Quoted in Curran, p. 31. - ^

This article incorporates public domain material from STS106-705-9. National Aeronautics and Space Administration.

This article incorporates public domain material from STS106-705-9. National Aeronautics and Space Administration.

- ^ Jerzy Wala, The Eight-Thousand-Metre Peaks of the Karakoram, Orographical Sketch Map, The Climbing Company Ltd/Cordee, 1994.

- ^ Charles S. Houston (1953) K2, the Savage Mountain. McGraw-Hill.

- ^ [1] "Confessions of Aleister Crowley, Chapter 16"

- ^ A timeline of human activity on K2

- ^ Booth, Martin (2001) [2000]. "Rhythms of Rapture". A Magick Life: A Biography of Aleister Crowley (Coronet ed.). London: Hodder and Stoughton. pp. 152–157. ISBN 0-340-71806-4.

{{cite book}}:|format=requires|url=(help) - ^ Curran, Jim (1995). K2: The Story of the Savage Mountain. Hodder & Stoughton. pp. 65–72. ISBN 978-0340660072.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Houston, Charles S (1939). Five Miles High. Dodd, Mead. ISBN 978-1585740512.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) Reprinted (2000) by First Lyon Press with introduction by Jim Wickwire - ^ Curran, pp.73–80

- ^ Kaufman, Andrew J. (1992). K2: The 1939 Tragedy. Mountaineers Books. ISBN 978-0898863239.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Curran pp.81–94

- ^ Houston, Charles S (1954). K2 – The Savage Mountain. Mc-Graw-Hill Book Company Inc. ISBN 978-1585740130.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) Reprinted (2000) by First Lyon Press with introduction by Jim Wickwire - ^ McDonald, Bernadette (2007). Brotherhood of the Rope – The Biography of Charles Houston. The Mountaineers Books. pp. 119–140. ISBN 978-0898869422.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|co-authors=(help) - ^ Curran, Jim (1995). K2: The Story of the Savage Mountain. Hodder & Stoughton. pp. 95–103. ISBN 978-0340660072.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|co-authors=(help) - ^ Curran, Jim (1995). K2: The Story of the Savage Mountain. Hodder & Stoughton. pp. Appendix I. ISBN 978-0340660072.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|co-authors=(help) - ^ American Alpine Journal, 1979, pp. 1–18

- ^ American Alpine Journal, 1983, p. 295

- ^ Dozens Reach Top of K2

- ^ BBC, Planet Earth, "Mountains", Part Three

- ^ "Climber Lists: Everest, K2 and other 8000ers".

- ^ "Österreicherin bricht nach Tod ihres Gefährten Besteigung von K2 ab". Stern (in German).

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help) - ^ Altitude oxygen calculator online

- ^ a b c Andy Fanshawe and Stephen Venables, Himalaya Alpine-Style, Hodder and Stoughton, 1995, ISBN 0-340-64931-3

- ^ a b c Audrey Salkeld, editor, World Mountaineering, Bulfinch Press, 1998, ISBN 0-8212-2502-2

- ^ a b American Alpine Journal, 2005, p. 351–353

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

cnnwas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ a b American Alpine Journal, 1991, pp. 19–32

- ^ R. Messner and A. Gogna [1981] (1982) K2 Mountain of Mountains. Translated from German by A. Salked. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-520253-8

- ^ Muza, SR; Fulco, CS; Cymerman, A (2004). "Altitude Acclimatisation Guide". U.S. Army Research Inst. of Environmental Medicine Thermal and Mountain Medicine Division Technical Report (USARIEM-TN-04-05). Retrieved 5 March 2009.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Cymerman, A; Rock, PB. "Medical Problems in High Mountain Environments. A Handbook for Medical Officers". USARIEM-TN94-2. US Army Research Inst. of Environmental Medicine Thermal and Mountain Medicine Division Technical Report. Retrieved 5 March 2009.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

^ K2 is a Located in integral part of Indian State Jammu and Kasmhir, Pakistan has illegal claim on the area and is called as Pak occupied Kasmhir.

External links

- Blankonthemap The Northern Kashmir WebSite

- How high is K2 really? – Measurements in 1996 gave 8614.27±0.6 m a.m.s.l

- Aleister Crowley's account of the 1902 K2 expedition

- K2climb.net

- CNR meteo station

- The Mountain Areas Conservancy Project

- The climbing history of K2 from the first attempt in 1902 until the Italian success in 1954.

- Outside Online: The K2 Tragedy

- Template:PDFlink From Everest-K2 Posters

- "K2". SummitPost.org.

- "K2" Encyclopædia Britannica

- Map of K2

- List of ascents to December 2007 (in pdf format)

- 'K2: The Killing Peak' Men's Journal November 2008 feature

- Achille Compagnoni – Daily Telegraph obituary

- Dr Charles Houston – Daily Telegraph obituary