Bipolar disorder

| Bipolar disorder | |

|---|---|

| Specialty | Psychiatry, clinical psychology |

Bipolar disorder or bipolar affective disorder, historically known as manic–depressive disorder, is a psychiatric diagnosis that describes a category of mood disorders defined by the presence of one or more episodes of abnormally elevated energy levels, cognition, and mood with or without one or more depressive episodes. The elevated moods are clinically referred to as mania or, if milder, hypomania. Individuals who experience manic episodes also commonly experience depressive episodes, or symptoms, or a mixed state in which features of both mania and depression are present at the same time.[2] These events are usually separated by periods of "normal" mood; but, in some individuals, depression and mania may rapidly alternate, which is known as rapid cycling. Severe manic episodes can sometimes lead to such psychotic symptoms as delusions and hallucinations. The disorder has been subdivided into bipolar I, bipolar II, cyclothymia, and other types, based on the nature and severity of mood episodes experienced; the range is often described as the bipolar spectrum.

Estimates of the lifetime prevalence of bipolar disorder vary, with studies typically giving values of the order of 1%, with higher figures given in studies with looser definitions of the condition.[3] According to other trials community samples lifetime prevalence varies from 0.4% to 1.6%.[4] The onset of full symptoms generally occurs in late adolescence or young adulthood. Diagnosis is based on the person's self-reported experiences, as well as observed behavior. Episodes of abnormality are associated with distress and disruption and an elevated risk of suicide, especially during depressive episodes. In some cases, it can be a devastating long-lasting disorder. In others, it has also been associated with creativity, goal striving, and positive achievements. There is significant evidence to suggest that many people with creative talents have also suffered from some form of bipolar disorder.[5] It is often suggested that creativity and bipolar disorder are linked.

Genetic factors contribute substantially to the likelihood of developing bipolar disorder, and environmental factors are also implicated. Bipolar disorder is often treated with mood stabilizing medications and, sometimes, other psychiatric drugs. Psychotherapy also has a role, often when there has been some recovery of the subject's stability. In serious cases, in which there is a risk of harm to oneself or others, involuntary commitment may be used. These cases generally involve severe manic episodes with dangerous behavior or depressive episodes with suicidal ideation. There are widespread problems with social stigma, stereotypes, and prejudice against individuals with a diagnosis of bipolar disorder.[6] People with bipolar disorder exhibiting psychotic symptoms can sometimes be misdiagnosed as having schizophrenia, a serious mental illness.[7]

The current term bipolar disorder is of fairly recent origin and refers to the cycling between high and low episodes (poles). A relationship between mania and melancholia had long been observed, although the basis of the current conceptualisation can be traced back to French psychiatrists in the 1850s. The term "manic-depressive illness" or psychosis was coined by German psychiatrist Emil Kraepelin in the late nineteenth century, originally referring to all kinds of mood disorder. German psychiatrist Karl Leonhard split the classification again in 1957, employing the terms unipolar disorder (major depressive disorder) and bipolar disorder.

Signs and symptoms

Bipolar disorder is a condition in which people experience abnormally elevated (manic or hypomanic) and, in many cases, abnormally depressed states for periods of time in a way that interferes with functioning. Not everyone's symptoms are the same, and there is no simple physiological test to confirm the disorder. Bipolar disorder can appear to be unipolar depression. Diagnosing bipolar disorder is often difficult, even for mental health professionals. What distinguishes bipolar disorder from unipolar depression is that the affected person experiences states of mania and depression. Often bipolar is inconsistent among patients because some people feel depressed more often than not and experience little mania whereas others experience predominantly manic symptoms. Additionally, the younger the age of onset—bipolar disorder starts in childhood or early adulthood in most patients—the more likely the first few episodes are to be depression.[8] Because a bipolar diagnosis requires a manic or hypomanic episode, many patients are initially diagnosed and treated as having major depression.

Depressive episode

Signs and symptoms of the depressive phase of bipolar disorder include persistent feelings of sadness, anxiety, guilt, anger, isolation, or hopelessness; disturbances in sleep and appetite; fatigue and loss of interest in usually enjoyable activities; problems concentrating; loneliness, self-loathing, apathy or indifference; depersonalization; loss of interest in sexual activity; shyness or social anxiety; irritability, chronic pain (with or without a known cause); lack of motivation; and morbid suicidal ideation.[9] In severe cases, the individual may become psychotic, a condition also known as severe bipolar depression with psychotic features. These symptoms include delusions or, less commonly, hallucinations, usually unpleasant.[10] A major depressive episode persists for at least two weeks, and may continue for over six months if left untreated.[11]

Manic episode

Mania is the signature characteristic of bipolar disorder and, depending on its severity, is how the disorder is classified. Mania is generally characterized by a distinct period of an elevated mood, which can take the form of euphoria. People commonly experience an increase in energy and a decreased need for sleep, with many often getting as little as 3 or 4 hours of sleep per night, while others can go days without sleeping.[12] A person may exhibit pressured speech, with thoughts experienced as racing.[13] Attention span is low, and a person in a manic state may be easily distracted. Judgment may become impaired, and sufferers may go on spending sprees or engage in behavior that is quite abnormal for them. They may indulge in substance abuse, particularly alcohol or other depressants, cocaine or other stimulants, or sleeping pills. Their behavior may become aggressive, intolerant, or intrusive. People may feel out of control or unstoppable, or as if they have been "chosen" and are "on a special mission" or have other grandiose or delusional ideas. Sexual drive may increase. At more extreme phases of bipolar I, a person in a manic state can begin to experience psychosis, or a break with reality, where thinking is affected along with mood.[14] Some people in a manic state experience severe anxiety and are very irritable (to the point of rage), while others are euphoric and grandiose.

To be diagnosed with mania according to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM), a person must experience this state of elevated or irritable mood, as well as other symptoms, for at least one week, less if hospitalization is required.[15]

Severity of manic symptoms can be measured by rating scales such as self-reported Altman Self-Rating Mania Scale[16] and clinician-based Young Mania Rating Scale.[17]

Hypomanic episode

Hypomania is generally a mild to moderate level of mania, characterized by optimism, pressure of speech and activity, and decreased need for sleep. Generally, hypomania does not inhibit functioning like mania.[18] Many people with hypomania are actually in fact more productive than usual, while manic individuals have difficulty completing tasks due to a shortened attention span. Some people have increased creativity while others demonstrate poor judgment and irritability. Many people experience signature hypersexuality. These persons generally have increased energy and tend to become more active than usual. They do not, however, have delusions or hallucinations. Hypomania can be difficult to diagnose because it may masquerade as mere happiness, though it carries the same risks as mania.

Hypomania may feel good to the person who experiences it. Thus, even when family and friends learn to recognize the mood swings, the individual often will deny that anything is wrong.[19] Also, the individual may not be able to recall the events that took place while they were experiencing hypomania.[8] What might be called a "hypomanic event", if not accompanied by complementary depressive episodes ("downs", etc.), is not typically deemed as problematic: The "problem" arises when mood changes are uncontrollable and, more importantly, volatile or "mercurial". If unaccompanied by depressive counterpart episodes or otherwise general irritability, this behavior is typically called hyperthymia, or happiness, which is, of course, perfectly normal. [citation needed] Indeed, the most elementary definition of bipolar disorder is an often "violent" or "jarring" state of essentially uncontrollable oscillation between hyperthymia and dysthymia. If left untreated, an episode of hypomania can last anywhere from a few days to several years. Most commonly, symptoms continue for a few weeks to a few months.[20]

Mixed affective episode

In the context of bipolar disorder, a mixed state is a condition during which symptoms of mania and clinical depression occur simultaneously.[21] Typical examples include tearfulness during a manic episode or racing thoughts during a depressive episode. Individuals may also feel incredibly frustrated in this state, since one may feel like a failure and at the same time have a flight of ideas. Mixed states are often the most dangerous period of mood disorders, during which substance abuse, panic disorder, suicide attempts, and other complications increase greatly.[22]

Associated features

Associated features are clinical phenomena that often accompany the disorder but are not part of the diagnostic criteria for the disorder. There are several childhood precursors in children who later receive a diagnosis of bipolar disorder. They may show subtle early traits such as mood abnormalities, full major depressive episodes, and ADHD.[23] BD is also accompanied by changes in cognitive processes and abilities. This include reduced attentional and executive capabilities and impaired memory. How the individual processes the world also depends on the phase of the disorder, with differential characteristics between the manic, hypomanic and depressive states.[24] Some studies have found a significant association between bipolar disorder and creativity.[25]

Causes

The causes of bipolar disorder likely vary between individuals. Twin studies have been limited by relatively small sample sizes but have indicated a substantial genetic contribution, as well as environmental influence. For bipolar I, the (probandwise) concordance rates in modern studies have been consistently put at around 40% in monozygotic twins (same genes), compared to 0 to 10% in dizygotic twins.[26] A combination of bipolar I, II and cyclothymia produced concordance rates of 42% vs 11%, with a relatively lower ratio for bipolar II that likely reflects heterogeneity. The overall heritability of the bipolar spectrum has been put at 0.71.[27] There is overlap with unipolar depression and if this is also counted in the co-twin the concordance with bipolar disorder rises to 67% in monozigotic twins and 19% in dizigotic.[28] The relatively low concordance between dizygotic twins brought up together suggests that shared family environmental effects are limited, although the ability to detect them has been limited by small sample sizes.[27]

Genetic

Genetic studies have suggested many chromosomal regions and candidate genes appearing to relate to the development of bipolar disorder, but the results are not consistent and often not replicated.[29]

Although the first genetic linkage finding for mania was in 1969,[30] the linkage studies have been inconsistent.[31] Meta-analyses of linkage studies detected either no significant genome-wide findings or, using a different methodology, only two genome-wide significant peaks, on chromosome 6q and on 8q21.[citation needed] Genome-wide association studies neither brought a consistent focus — each has identified new loci.[31]

Findings point strongly to heterogeneity, with different genes being implicated in different families.[32] A review seeking to identify the more consistent findings suggested several genes related to serotonin (SLC6A4 and TPH2), dopamine (DRD4 and SLC6A3), glutamate (DAOA and DTNBP1), and cell growth and/or maintenance pathways (NRG1, DISC1 and BDNF), although noting a high risk of false positives in the published literature. It was also suggested that individual genes are likely to have only a small effect and to be involved in some aspect related to the disorder (and a broad range of "normal" human behavior) rather than the disorder per se.[33]

Advanced paternal age has been linked to a somewhat increased chance of bipolar disorder in offspring, consistent with a hypothesis of increased new genetic mutations.[34]

Physiological

Abnormalities in the structure and/or function of certain brain circuits could underlie bipolar. Two meta-analyses of MRI studies in bipolar disorder report an increase in the volume of the lateral ventricles, globus pallidus and increase in the rates of deep white matter hyperintensities.[35][36]

The "kindling" theory asserts that people who are genetically predisposed toward bipolar disorder can experience a series of stressful events,[37] each of which lowers the threshold at which mood changes occur. Eventually, a mood episode can start (and become recurrent) by itself. There is evidence of hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis (HPA axis) abnormalities in bipolar disorder due to stress.[38]

Other brain components which have been proposed to play a role are the mitochondria,[39] and a sodium ATPase pump,[40] causing cyclical periods of poor neuron firing (depression) and hypersensitive neuron firing (mania). This may only apply for type one, but type two apparently results from a large confluence of factors.[citation needed] Circadian rhythms and melatonin activity also seem to be altered.[41]

Environmental

Evidence suggests that environmental factors play a significant role in the development and course of bipolar disorder, and that individual psychosocial variables may interact with genetic dispositions.[33] There is fairly consistent evidence from prospective studies that recent life events and interpersonal relationships contribute to the likelihood of onsets and recurrences of bipolar mood episodes, as they do for onsets and recurrences of unipolar depression.[42] There have been repeated findings that between a third and a half of adults diagnosed with bipolar disorder report traumatic/abusive experiences in childhood, which is associated on average with earlier onset, a worse course, and more co-occurring disorders such as PTSD.[43] The total number of reported stressful events in childhood is higher in those with an adult diagnosis of bipolar spectrum disorder compared to those without, particularly events stemming from a harsh environment rather than from the child's own behavior.[44] Early experiences of adversity and conflict are likely to make subsequent developmental challenges in adolescence more difficult, and are likely a potentiating factor in those at risk of developing bipolar disorder.[45]

Diagnosis

Diagnosis is based on the self-reported experiences of an individual as well as abnormalities in behavior reported by family members, friends or co-workers, followed by secondary signs observed by a psychiatrist, nurse, social worker, clinical psychologist or other clinician in a clinical assessment. There are lists of criteria for someone to be so diagnosed. These depend on both the presence and duration of certain signs and symptoms. Assessment is usually done on an outpatient basis; admission to an inpatient facility is considered if there is a risk to oneself or others. The most widely used criteria for diagnosing bipolar disorder are from the American Psychiatric Association's Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, the current version being DSM-IV-TR, and the World Health Organization's International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, currently the ICD-10. The latter criteria are typically used in Europe and other regions while the DSM criteria are used in the USA and other regions, as well as prevailing in research studies.

An initial assessment may include a physical exam by a physician. Although there are no biological tests which confirm bipolar disorder, tests may be carried out to exclude medical illnesses such as hypo- or hyperthyroidism, metabolic disturbance, a systemic infection or chronic disease, and syphilis or HIV infection. An EEG may be used to exclude epilepsy, and a CT scan of the head to exclude brain lesions. Investigations are not generally repeated for relapse unless there is a specific medical indication.

Several rating scales for the screening and evaluation of BD exist, such as the Bipolar spectrum diagnostic scale.[46] The use of evaluation scales can not substitute a full clinical interview but they serve to systematize the recollection of symptoms.[46] On the other hand instruments for the screening of BD have low sensitivity and limited diagnostic validity.[46]

Criteria and subtypes

There is no clear consensus as to how many types of bipolar disorder exist.[47] In DSM-IV-TR and ICD-10, bipolar disorder is conceptualized as a spectrum of disorders occurring on a continuum. The DSM-IV-TR lists three specific subtypes and one for non-specified:[48]

- Bipolar I disorder

- One or more manic episodes. Subcategories specify whether there has been more than one episode, and the type of the most recent episode.[49] A depressive or hypomanic episode is not required for diagnosis, but it frequently occurs.

- Bipolar II disorder

- No manic episodes, but one or more hypomanic episodes and one or more major depressive episode.[50] However, a bipolar II diagnosis is not a guarantee that they will not eventually suffer from such an episode in the future.[citation needed] Hypomanic episodes do not go to the full extremes of mania (i.e., do not usually cause severe social or occupational impairment, and are without psychosis), and this can make bipolar II more difficult to diagnose, since the hypomanic episodes may simply appear as a period of successful high productivity and is reported less frequently than a distressing, crippling depression.

- Cyclothymia

- A history of hypomanic episodes with periods of depression that do not meet criteria for major depressive episodes.[51] There is a low-grade cycling of mood which appears to the observer as a personality trait, and interferes with functioning.

- Bipolar Disorder NOS (Not Otherwise Specified)

- This is a catchall category, diagnosed when the disorder does not fall within a specific subtype.[52] Bipolar NOS can still significantly impair and adversely affect the quality of life of the patient.

The bipolar I and II categories have specifiers that indicate the presentation and course of the disorder. For example, the "with full interepisode recovery" specifier applies if there was full remission between the two most recent episodes.[53]

Rapid cycling

Most people who meet criteria for bipolar disorder experience a number of episodes, on average 0.4 to 0.7 per year, lasting three to six months.[54] Rapid cycling, however, is a course specifier that may be applied to any of the above subtypes. It is defined as having four or more episodes per year and is found in a significant fraction of individuals with bipolar disorder. The definition of rapid cycling most frequently cited in the literature (including the DSM) is that of Dunner and Fieve: at least four major depressive, manic, hypomanic or mixed episodes are required to have occurred during a 12-month period.[55] Ultra-rapid (days) or ultra-ultra rapid or ultradian (within a day) cycling have also been described.[56]

Differential diagnosis

There are several other mental disorders which may involve similar symptoms to bipolar disorder. These include schizophrenia,[57] schizoaffective disorder, drug intoxication, brief drug-induced psychosis, schizophreniform disorder and borderline personality disorder. Both borderline personality and bipolar disorder can involve what are referred to as "mood swings". In bipolar disorder, the term refers to the cyclic episodes of elevated and depressed mood which generally last weeks or months. The term in borderline personality refers to the marked lability and reactivity of mood, known as emotional dysregulation, due to response to external psychosocial and intrapsychic stressors; these may arise or subside suddenly and dramatically and last for seconds, minutes, hours or days. A bipolar depression is generally more pervasive with sleep, appetite disturbance and nonreactive mood, whereas the mood in dysthymia of borderline personality remains markedly reactive and sleep disturbance not acute.[58] Some hold that borderline personality disorder represents a subthreshold form of mood disorder while others maintain the distinctness, though noting they often coexist.[59]

Challenges

The experiences and behaviors involved in bipolar disorder are often not understood by individuals or recognized by mental health professionals, so diagnosis may sometimes be delayed for over 10 years.[60] The treatment lag is apparently not decreasing, even though there is increased public awareness of the condition.

Individuals are commonly misdiagnosed.[61] An individual may appear simply depressed when they are seen by a health professional. This can result in misdiagnosis of Major Depressive Disorder. However, there is also a long-standing issue in the research literature as to whether a categorical classificatory divide between unipolar and bipolar depression is actually valid, or whether it is more accurate to talk of a continuum involving dimensions of depression and mania.[62][63]

It has been noted that the bipolar disorder diagnosis is officially characterised in historical terms such that, technically, anyone with a history of (hypo)mania and depression has bipolar disorder whatever their current or future functioning and vulnerability. This has been described as "an ethical and methodological issue", as it means no one can be considered as being recovered (only "in remission") from bipolar disorder according to the official criteria. This is considered especially problematic given that brief hypomanic episodes are widespread among people generally and not necessarily associated with dysfunction.[24]

Flux is the fundamental nature of bipolar disorder.[64] Individuals with the illness have continual changes in energy, mood, thought, sleep, and activity. The diagnostic subtypes of bipolar disorder are thus static descriptions—snapshots, perhaps—of an illness in continual flux, with a great diversity of symptoms and varying degrees of severity. Individuals may stay in one subtype, or change into another, over the course of their illness.[65] The DSM-V, to be published in 2013, will likely include further and more accurate sub-typing (Akiskal and Ghaemi, 2006).

The diagnosis of bipolar disorder can be complicated by coexisting psychiatric conditions such as obsessive-compulsive disorder, social phobia, panic disorder, or attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Substance abuse may predate the appearance of bipolar symptoms, further complicating the diagnosis. A careful longitudinal analysis of symptoms and episodes, enriched if possible by discussions with friends and family members, is crucial to establishing a treatment plan where these comorbidities exist.[66]

Management

There are a number of pharmacological and psychotherapeutic techniques used to treat bipolar disorder. Individuals may use self-help and pursue recovery.

Hospitalization may be required especially with the manic episodes present in bipolar I. This can be voluntary or (if mental health legislation allows and varying state-to-state regulations in the USA) involuntary (called civil or involuntary commitment). Long-term inpatient stays are now less common due to deinstitutionalization, although these can still occur.[67] Following (or in lieu of) a hospital admission, support services available can include drop-in centers, visits from members of a community mental health team or Assertive Community Treatment team, supported employment and patient-led support groups, intensive outpatient programs. These are sometimes referred to partial-inpatient programs.[68]

Psychosocial

Psychotherapy is aimed at alleviating core symptoms, recognizing episode triggers, reducing negative expressed emotion in relationships, recognizing prodromal symptoms before full-blown recurrence, and, practicing the factors that lead to maintenance of remission[69] Cognitive behavioural therapy, family-focused therapy, and psychoeducation have the most evidence for efficacy in regard to relapse prevention, while interpersonal and social rhythm therapy and cognitive-behavioural therapy appear the most effective in regard to residual depressive symptoms. Most studies have been based only on bipolar I, however, and treatment during the acute phase can be a particular challenge.[70] Some clinicians emphasize the need to talk with individuals experiencing mania, to develop a therapeutic alliance in support of recovery.[71]

Medication

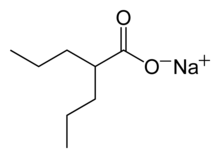

The mainstay of treatment is a mood stabilizers such as lithium carbonate or lamotrigine.[72][73] Lamotrigine has been found to be best for preventing depressions, while lithium is the only drug proven to reduce suicide in people with bipolar disorder.[74] These two drugs comprise several unrelated compounds which have been shown to be effective in preventing relapses of manic, or in the one case, depressive episodes. The first known and "gold standard" mood stabilizer is lithium,[75] while almost as widely used is sodium valproate,[76] also used as an anticonvulsant. Other anticonvulsants used in bipolar disorder include carbamazepine, reportedly more effective in rapid cycling bipolar disorder, and lamotrigine, which is the first anticonvulsant shown to be of benefit in bipolar depression.[77] Depending on the severity of the case, anti-convulsants may be used in combination with lithium-based products or on their own.[78]

Atypical antipsychotics have been found to be effective in managing mania associated with bipolar disorder.[79] Antidepressants have not been found to be of any benefit over that found with mood stabilizers.[79]

Omega 3 fatty acids, in addition to normal pharmacological treatment, may have beneficial effects on depressive symptoms, although studies have been scarce and of variable quality.[80] The effectiveness of topiramate is unknown.[81]

Patient Teaching [4]

Activity

Appropriate pacing of activities should be emphasized for effective pain management, and cognitive-behavioral self-regulation training may be emphasized to enhance effectiveness of pain-management coping.

Prevention

Patients may be taught to recognize incipient signs of mood shifts and associated behaviors to reduce vulnerability to future episodes and signal the need for consultation with appropriate health care provider to adjust treatment.

Prognosis

For many individuals with bipolar disorder a good prognosis results from good treatment, which, in turn, results from an accurate diagnosis. Because bipolar disorder can have a high rate of both under-diagnosis and misdiagnosis,[8] it is often difficult for individuals with the condition to receive timely and competent treatment.

Bipolar disorder can be a severely disabling medical condition. However, many individuals with bipolar disorder can live full and satisfying lives. Quite often, medication is needed to enable this. Persons with bipolar disorder may have periods of normal or near normal functioning between episodes.[82]

Prognosis depends on many factors such as the right medicines and dosage, comprehensive knowledge of the disease and its effects; a positive relationship with a competent medical doctor and therapist; and good physical health, which includes exercise, nutrition, and a regulated stress level. There are other factors that lead to a good prognosis, such as being very aware of small changes in a person's energy, mood, sleep and eating behaviors.[83]

Functioning

A recent 20-year prospective study on bipolar I and II found that functioning varied over time along a spectrum from good to fair to poor. During periods of major depression or mania (in BPI), functioning was on average poor, with depression being more persistently associated with disability than mania. Functioning between episodes was on average good — more or less normal. Subthreshold symptoms were generally still substantially impairing, however, except for hypomania (below or above threshold) which was associated with improved functioning.[84]

Another study confirmed the seriousness of the disorder as "the standardized all-cause mortality ratio among patients with BD is increased approximately two-fold." Bipolar disorder is currently regarded "as possibly the most costly category of mental disorders in the United States." Episodes of abnormality are associated with distress and disruption, and an elevated risk of suicide, especially during depressive episodes.[85]

Recovery and recurrence

A naturalistic study from first admission for mania or mixed episode (representing the hospitalized and therefore most severe cases) found that 50% achieved syndromal recovery (no longer meeting criteria for the diagnosis) within six weeks and 98% within two years. 72% achieved symptomatic recovery (no symptoms at all) and 43% achieved functional recovery (regaining of prior occupational and residential status). However, 40% went on to experience a new episode of mania or depression within 2 years of syndromal recovery, and 19% switched phases without recovery.[86]

Symptoms preceding a relapse (prodromal), specially those related to mania, can be reliably identified by people with BD.[87] There have been intents to teach patients coping strategies when noticing such symptoms with encouraging results.[88]

Mortality

Bipolar disorder can cause suicidal ideation that leads to suicidal attempts. One out of 3 people with bipolar disorder report past attempts of suicide or complete it,[89] and the annual average suicide rate is 0.4%, which is 10 to 20 times that of the general population.[90] The standardized mortality ratio from suicide in BD is between 18 and 25.[91]

Epidemiology

When broadly defined 4% of people experience bipolar at some point in their life.[92] The lifetime prevalence of bipolar disorder type I, which includes at least a lifetime manic episode, has generally been estimated at 2%.[93] It is equally prevalent in men and women and is found across all cultures and ethnic groups.[94]

A reanalysis of data from the National Epidemiological Catchment Area survey in the United States, however, suggested that 0.8 percent experience a manic episode at least once (the diagnostic threshold for bipolar I) and 0.5 a hypomanic episode (the diagnostic threshold for bipolar II or cyclothymia). Including sub-threshold diagnostic criteria, such as one or two symptoms over a short time-period, an additional 5.1 percent of the population, adding up to a total of 6.4 percent, were classed as having a bipolar spectrum disorder.[95] A more recent analysis of data from a second US National Comorbidity Survey found that 1% met lifetime prevalence criteria for bipolar 1, 1.1% for bipolar II, and 2.4% for subthreshold symptoms.[96] There are conceptual and methodological limitations and variations in the findings. Prevalence studies of bipolar disorder are typically carried out by lay interviewers who follow fully structured/fixed interview schemes; responses to single items from such interviews may suffer limited validity. In addition, diagnosis and prevalence rates are dependent on whether a categorical or spectrum approach is used. Concerns have arisen about the potential for both underdiagnosis and overdiagnosis.[97]

Late adolescence and early adulthood are peak years for the onset of bipolar disorder.[98][99] One study also found that in 10% of bi-polar cases, the onset of mania had happened after the patient had turned 50.[100]

History

Variations in moods and energy levels have been observed as part of the human experience since time immemorial. The words "melancholia" (an old word for depression) and "mania" have their etymologies in Ancient Greek. The word melancholia is derived from melas/μελας, meaning "black", and chole/χολη, meaning "bile" or "gall",[101] indicative of the term's origins in pre-Hippocratic humoral theories. Within the humoral theories, mania was viewed as arising from an excess of yellow bile, or a mixture of black and yellow bile. The linguistic origins of mania, however, are not so clear-cut. Several etymologies are proposed by the Roman physician Caelius Aurelianus, including the Greek word ‘ania’, meaning to produce great mental anguish, and ‘manos’, meaning relaxed or loose, which would contextually approximate to an excessive relaxing of the mind or soul (Angst and Marneros 2001). There are at least five other candidates, and part of the confusion surrounding the exact etymology of the word mania is its varied usage in the pre-Hippocratic poetry and mythologies (Angst and Marneros 2001).

The basis of the current conceptualisation of manic-depressive illness can be traced back to the 1850s; on January 31, 1854, Jules Baillarger described to the French Imperial Academy of Medicine a biphasic mental illness causing recurrent oscillations between mania and depression, which he termed folie à double forme (‘dual-form insanity’).[102] Two weeks later, on February 14, 1854, Jean-Pierre Falret presented a description to the Academy on what was essentially the same disorder, and designated folie circulaire (‘circular insanity’) by him.(Sedler 1983) The two bitterly disputed as to who had been the first to conceptualise the condition.

These concepts were developed by the German psychiatrist Emil Kraepelin (1856–1926), who, using Kahlbaum's concept of cyclothymia,[103] categorized and studied the natural course of untreated bipolar patients. He coined the term manic depressive psychosis, after noting that periods of acute illness, manic or depressive, were generally punctuated by relatively symptom-free intervals where the patient was able to function normally.[104]

The term "manic-depressive reaction" appeared in the first American Psychiatric Association Diagnostic Manual in 1952, influenced by the legacy of Adolf Meyer who had introduced the paradigm illness as a reaction of biogenetic factors to psychological and social influences.[105] Subclassification of bipolar disorder was first proposed by German psychiatrist Karl Leonhard in 1957; he was also the first to introduce the terms bipolar (for those with mania) and unipolar (for those with depressive episodes only).[106]

Society and culture

Stigma

There are widespread problems with social stigma, stereotypes, and prejudice against individuals with a diagnosis of bipolar disorder.[6]

Cultural references

Kay Redfield Jamison, a clinical psychologist and Professor of Psychiatry at the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, profiled her own bipolar disorder in her memoir An Unquiet Mind (1995).[107] In her book, Touched with Fire (1993), she argued for a connection between bipolar disorder and artistic creativity.[108]

Several films have portrayed characters with traits suggestive of the diagnosis that has been the subject of discussion by psychiatrists and film experts alike. A notable example is Mr. Jones (1993), in which Mr. Jones (Richard Gere) swings from a manic episode into a depressive phase and back again, spending time in a psychiatric hospital and displaying many of the features of the syndrome.[109] In The Mosquito Coast (1986), Allie Fox (Harrison Ford) displays some features including recklessness, grandiosity, increased goal-directed activity and mood lability, as well as some paranoia.[110]

In the Australian TV drama Stingers, Detective Luke Harris (Gary Sweet) is portrayed as having bipolar disorder and shows how his paranoia interfered with his work. As research for the role, Sweet visited a psychiatrist to learn about manic-depressive illness. He said that he left the sessions convinced he had the condition. TV specials, for example the BBC's The Secret Life of the Manic Depressive,[111] MTV's True Life: I'm Bipolar, talk shows, and public radio shows, and the greater willingness of public figures to discuss their own bipolar disorder, have focused on psychiatric conditions, thereby, raising public awareness.

On April 7, 2009, the nighttime drama 90210 on the CW network, aired a special episode where the character Silver was diagnosed with bipolar disorder. A public service announcement (PSA) aired after the episode, directing teens and young adults to the Child and Adolescent Bipolar Foundation website for information and to chat with other teens.[112]

Stacey Slater, a character from the popular BBC soap EastEnders, has been diagnosed with the disorder. After losing her friend Danielle Jones, Stacey began acting strangely; and the character had to come to terms with the prospect that, like her mother, Jean Slater, she suffers from bipolar disorder. The high-profile storyline was developed as part of the BBC's Headroom campaign.[113] The Channel 4 soap Brookside had earlier featured a story about bipolar disorder when the character Jimmy Corkhill was diagnosed with the condition.[114] Dean Sullivan, the actor who played Jimmy, was presented with a Special Achievement Award at the 2003 British Soap Awards for the role.[114]

Specific populations

In children

Emil Kraepelin in the 1920s noted that mania episodes were rare before puberty.[115] In general BD in children was not recognized in the first half of the twentieth century. This issue diminished with an increased following of the DSM criteria in the last part of the twentieth century.[115][116]

While in adults the course of BD is characterized by discrete episodes of depression and mania with no clear symptomatology between them, in chidren and adolescents very fast mood changes or even chronic symptoms are the norm.[117] On the other hand pediactric BD instead of euphoric mania commonly develops with outbursts of anger, irritability and psychosis, less common in adults.[115][117]

The diagnosis of childhood BD is controversial,[117] although it is not under discussion that BD typical symptoms have negative consequences for minors suffering them.[115] Main discussion is centered on whether what is called BD in children refers to the same disorder than when diagnosing adults,[115] and the related question on whether adults criteria for diagnosis are useful and accurate when applied to children.[117] Regarding diagnosis of children some experts recommend to follow the DSM criteria.[117] Others believe that these criteria do not separate correctly children with BD from other problems such as ADHD, and emphasize fast mood cycles.[117] Still others argue that what accurately differentiates children with BD is irritability.[117] The practice parameters of the AACAP encourage the first strategy.[115][117] American children and adolescents diagnosed of BD in community hospitals increased 4-fold reaching rates of up to 40% in 10 years around the beginning of the current century, while in outpatient clinics it doubled reaching the 6%.[117] The data suggest that doctors had been more aggressively applying the diagnosis to children.[citation needed] The reasons for this increase are unclear. Consensus regarding the diagnosis in the pediatric age seems to apply only to the USA.[citation needed] Studies using DSM criteria show that up to 1% of youth may have BD.[115]

Treatment involves medication and psychotherapy.[117] Drug prescription usually consists in mood stabilizers and atypical antipsychotics.[117] Among the formers lithium is the only compound approved by the FDA for children.[115] Psychological treatment combines normally education on the disease, group therapy and cognitive behavioral therapy.[117] Chronic medication is often needed.[117]

Current research directions for BD in children include optimizing treatments, increasing the knowledge of the genetic and neurobiological basis of the pediatric disorder and improving diagnostic criteria.[117] The DSM-V has proposed a new diagnosis which is considered to cover some presentations currently thought of as childhood-onset bipolar.[118][119]

In the elderly

There is a relative lack of knowledge about bipolar disorder in late life. There is evidence that it becomes less prevalent with age but nevertheless accounts for a similar percentage of psychiatric admissions; that older bipolar patients had first experienced symptoms at a later age; that later onset of mania is associated with more neurologic impairment; that substance abuse is considerably less common in older groups; and that there is probably a greater degree of variation in presentation and course, for instance individuals may develop new-onset mania associated with vascular changes, or become manic only after recurrent depressive episodes, or may have been diagnosed with bipolar disorder at an early age and still meet criteria. There is also some weak evidence that mania is less intense and there is a higher prevalence of mixed episodes, although there may be a reduced response to treatment. Overall there are likely more similarities than differences from younger adults.[120] In the elderly, recognition and treatment of bipolar disorder may be complicated by the presence of dementia or the side effects of medications being taken for other conditions.[121]

See also

- Bipolar disorders research

- Postpartum psychosis Puerperal bipolar disorder

References

- ^ Blumer D (2002). "The Illness of Vincent van Gogh". Am J Psychiatry. 159 (4): 519–26. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.159.4.519. PMID 11925286.

- ^ Basco, Monica Ramirez (2006). The Bipolar Workbook: Tools for Controlling Your Mood Swings. New York: The Guilford Press. p. viii. ISBN 1593851626.

- ^ Yatham, Lakshmi (2010). Bipolar Disorder. New York: Wiley. p. 53. ISBN 0470721987.

- ^ a b Bipolar Disorder Retrieved 15th October, 2011

- ^ Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi:10.1016/S0165-0327(02)00462-7, please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

|doi=10.1016/S0165-0327(02)00462-7instead. - ^ a b "Stigma and Bipolar Disorder". NIMH. February 21, 2009. Retrieved 2010-11-08.

- ^ "What are the symptoms of bipolar disorder?". NIMH. April 15, 2009. Retrieved 2010-09-19.

- ^ a b c Bowden, Charles L., M.D. (January 2001). "Strategies to Reduce Misdiagnosis of Bipolar Depression". American Psychiatric Association. Retrieved 2010-12-06.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Bipolar Disorder: Signs and symptoms". Mayo Clinic.[dead link]

- ^ American Psychiatric Association 2000a, p. 412

- ^ American Psychiatric Association 2000a, p. 349

- ^ American Psychiatric Association (1994). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (4th edition). Washington, DC. pp357.

- ^ Read, Kimberly (2010-02-27). "Warning Signs of Mania". About.com. Retrieved 2010-12-06.

- ^ "NIMH · Bipolar Disorder: NIH Publication 08-3679, Revised 2008". Nimh.nih.gov. Retrieved 2011-01-15.

- ^ Mayo Clinic staff. "Bipolar disorder: Tests and diagnosis". MayoClinic.com. Retrieved 2010-07-19.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: postscript (link) - ^ Altman EG, Hedeker D, Peterson JL, Davis JM (1997). "The Altman Self-Rating Mania Scale". Biological Psychiatry. 42 (10): 948–55. doi:10.1016/S0006-3223(96)00548-3. PMID 9359982.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Young RC, Biggs JT, Ziegler VE, Meyer DA (1978). "A rating scale for mania: reliability, validity and sensitivity". Br J Psychiatry. 133 (5): 429–35. doi:10.1192/bjp.133.5.429. PMID 728692.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Hypomania and Mania Symptoms in Bipolar Disorder". WebMD.com. January 10, 2010.

- ^ "Bipolar Disorder: NIH Publication No. 95-3679". U.S. National Institutes of Health. September 1995. Archived from the original on 2008-04-29.

- ^ "Bipolar II Disorder Symptoms and Signs". Web M.D. Retrieved 2010-12-06.

- ^ "Bipolar Disorder: Complications". Mayo Clinic.[dead link]

- ^ Goldman E (1999). "Severe Anxiety, Agitation are Warning Signals of Suicide in Bipolar Patients". Clin Psychiatr News: 25.

- ^ Andreoli TE (1989). "Molecular aspects of endocrinology". Hosp. Pract. (Off. Ed.). 24 (8): 11–2. PMID 2504732.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ a b Mansell W, Pedley R (2008). "The ascent into mania: A review of psychological processes associated with the development of manic symptoms". Clinical Psychology Review. 28 (3): 494–520. doi:10.1016/j.cpr.2007.07.010. PMID 17825463.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Srivastava S, Ketter TA (2010). "The link between bipolar disorders and creativity: evidence from personality and temperament studies". Curr Psychiatry Rep. 12 (6): 522–30. doi:10.1007/s11920-010-0159-x. PMID 20936438.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Kieseppä T, Partonen T, Haukka J, Kaprio J, Lönnqvist J (2004). "High concordance of bipolar I disorder in a nationwide sample of twins". Am J Psychiatry. 161 (10): 1814–21. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.161.10.1814. PMID 15465978.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Edvardsen J, Torgersen S, Røysamb E; et al. (2008). "Heritability of bipolar spectrum disorders. Unity or heterogeneity". Journal of Affective Disorders. 106 (3): 229–40. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2007.07.001. PMID 17692389.

{{cite journal}}: C1 control character in|title=at position 67 (help); Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help); Invalid|ref=harv(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ McGuffin P, Rijsdijk F, Andrew M, Sham P, Katz R, Cardno A (2003). "The Heritability of Bipolar Affective Disorder and the Genetic Relationship to Unipolar Depression". Arch Gen Psychiatry. 60 (5): 497–502. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.60.5.497. PMID 12742871.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Kato T (2007). "Molecular genetics of bipolar disorder and depression". Psychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences. 61 (1): 3–19. doi:10.1111/j.1440-1819.2007.01604.x. PMID 17239033.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Reich T, Clayton PJ, Winokur G (April 1969). "Family history studies: V. The genetics of mania". Am J Psychiatry. 125 (10): 1358–69. PMID 5304735.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: year (link) - ^ a b Burmeister M, McInnis MG, Zöllner S (July 2008). "Psychiatric genetics: progress amid controversy". Nat Rev Genet. 9 (7): 527–540. doi:10.1038/nrg2381. PMID 18560438.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Segurado R, Detera-Wadleigh SD, Levinson DF, Lewis CM, Gill M, Nurnberger JI Jr, Craddock N; et al. (2003). "Genome Scan Meta-Analysis of Schizophrenia and Bipolar Disorder, Part III: Bipolar Disorder". Am J Hum Genet. 73 (1): 49–62. doi:10.1086/376547. PMC 1180589. PMID 12802785.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help); Invalid|ref=harv(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Serretti A, Mandelli L (2008). "The genetics of bipolar disorder: genome 'hot regions,' genes, new potential candidates and future directions". Molecular Psychiatry. 13 (8): 742–71. doi:10.1038/mp.2008.29. PMID 18332878.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Frans E, Sandin S, Reichenberg A, Lichtenstein P, Langstrom N, Hultman C (2008). "Advancing Paternal Age and Bipolar Disorder". Arch Gen Psychiatry. 65 (9): 1034–40. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.65.9.1034. PMID 18762589.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Kempton MJ, Geddes JR, Ettinger U; et al. (2008). "Meta-analysis, Database, and Meta-regression of 98 Structural Imaging Studies in Bipolar Disorder". Arch Gen Psychiatry. 65 (9): 1017–32. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.65.9.1017. PMID 18762588.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) see also MRI database at www.bipolardatabase.org. - ^ Arnone D, Cavanagh J, Gerber D, Lawrie SM, Ebmeier KP, McIntosh AM (2009). "Magnetic resonance imaging studies in bipolar disorder and schizophrenia: meta-analysis". Br J Psychiatry. 195 (3): 194–201. doi:10.1192/bjp.bp.108.059717. PMID 19721106.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Link and reference involving kindling theory[dead link]

- ^ Brian Koehler, Ph.D., The International Society for the Psychological Treatment Of Schizophrenia and Other Psychoses, Bipolar Disorder, Stress, and the HPA Axis, 2005.

- ^ Stork C, Renshaw PF (2005). "Mitochondrial dysfunction in bipolar disorder: evidence from magnetic resonance spectroscopy research". Mol. Psychiatry. 10 (10): 900–19. doi:10.1038/sj.mp.4001711. PMID 16027739.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Malcomb R. Brown (2004). Focus on Bipolar Disorder Research. Nova Science Publishers. p. 16. ISBN 978-1594540592.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Dallaspezia S, Benedetti F (2009). "Melatonin, circadian rhythms, and the clock genes in bipolar disorder". Curr Psychiatry Rep. 11 (6): 488–93. doi:10.1007/s11920-009-0074-1. PMID 19909672.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Alloy LB, Abramson LY, Urosevic S, Walshaw PD, Nusslock R, Neeren AM (2005). "The psychosocial context of bipolar disorder: Environmental, cognitive, and developmental risk factors". Clinical Psychology Review. 25 (8): 1043–75. doi:10.1016/j.cpr.2005.06.006. PMID 16140445.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Leverich GS, Post RM (April 2006). "Course of bipolar illness after history of childhood trauma". Lancet. 367 (9516): 1040–2. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68450-X. PMID 16581389.

- ^ Grandin LD, Alloy LB, Abramson LY (2007). "Childhood Stressful Life Events and Bipolar Spectrum Disorders". J Soc Clin Psychol. 26 (4): 460–478. doi:10.1521/jscp.2007.26.4.460.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Miklowitz DJ, Chan KD (2008). "Prevention of Bipolar Disorder in At-Risk Children: Theoretical Assumptions and Empirical Foundations". Dev Psychopathol. 20 (3): 881–897. doi:10.1017/S0954579408000424. PMC 2504732. PMID 18606036.

- ^ a b c Picardi A (2009). "Rating scales in bipolar disorder". Curr Opin Psychiatry. 22 (1): 42–9. doi:10.1097/YCO.0b013e328315a4d2. PMID 19122534.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Akiskal HS, Benazzi F (2006). "The DSM-IV and ICD-10 categories of recurrent [major] depressive and bipolar II disorders: evidence that they lie on a dimensional spectrum". J Affect Disord. 92 (1): 45–54. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2005.12.035. PMID 16488021.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 4th, text revision (DSM-IV-TR) ed. 2000. ISBN 0-89042-025-4. Bipolar Disorder.

- ^ DSM-IV-TR. Bipolar I Disorder.

- ^ DSM-IV-TR. Diagnostic criteria for 296.89 Bipolar II Disorder.

- ^ DSM-IV-TR. Diagnostic criteria for 301.13 Cyclothimic Disorder.

- ^ DSM-IV-TR. Not Otherwise Specified (NOS).

- ^ DSM-IV-TR. Longitudinal course specifiers for mood disorders.

- ^ Angst, J; Selloro, R (September 15, 2000). "Historical perspectives and natural history of bipolar disorder". Biological Psychiatry. 48 (6): 445–457. doi:10.1016/S0006-3223(00)00909-4. PMID 11018218.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - ^ Mackin, P; Young, AH (2004). "Rapid cycling bipolar disorder: historical overview and focus on emerging treatments". Bipolar Disorders. 6 (6): 523–529. doi:10.1111/j.1399-5618.2004.00156.x. PMID 15541068.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - ^ Tillman R, Geller B (2003). "Definitions of rapid, ultrarapid, and ultradian cycling and of episode duration in pediatric and adult bipolar disorders: a proposal to distinguish episodes from cycles". J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 13 (3): 267–71. doi:10.1089/104454603322572598. PMID 14642014.

- ^ Pope HG (1983). "Distinguishing bipolar disorder from schizophrenia in clinical practice: guidelines and case reports". Hospital and Community Psychiatry. 34: 322–28.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - ^ Goodwin & Jamison. pp. 108–110.

- ^ Magill CA (2004). "The boundary between borderline personality disorder and bipolar disorder: current concepts and challenges". Can J Psychiatry. 49 (8): 551–6. PMID 15453104.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ S. Nassir Ghaemi (2001). "Bipolar Disorder: How long does it usually take for someone to be diagnosed for bipolar disorder?". Archived from the original on December 7, 2006. Retrieved February 20, 2007.

- ^ Roy H. Perlis (2005). "Misdiagnosis of Bipolar Disorder". American Journal of Managed Care. Retrieved February 20, 2007.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - ^ Cuellar AK, Johnson SL, Winters R (May 2005). "Distinctions between bipolar and unipolar depression". Clin Psychol Rev. 25 (3): 307–339. doi:10.1016/j.cpr.2004.12.002. PMC 2850601. PMID 15792852.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Benazzi F (2007). "Is there a continuity between bipolar and depressive disorders?". Psychother Psychosom. 76 (2): 70–6. doi:10.1159/000097965. PMID 17230047.

- ^ "Depression and Bipolar Support Alliance: About Mood Disorders". Dbsalliance.org. Retrieved 2011-01-15.

- ^ Goodwin & Jamison, 1990.

- ^ Sagman D and Tohen M (2009). "Comorbidity in Bipolar Disorder: The Complexity of Diagnosis and Treatment". Psychiatric Times.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - ^ Becker T, Kilian R (2006). "Psychiatric services for people with severe mental illness across western Europe: what can be generalized from current knowledge about differences in provision, costs and outcomes of mental health care?". Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica Supplement. 429 (429): 9–16. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0447.2005.00711.x. PMID 16445476.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - ^ McGurk SR, Mueser KT, Feldman K, Wolfe R, Pascaris A (2007). "Cognitive Training for Supported Employment: 2-3 Year Outcomes of a Randomized Controlled Trial". American Journal of Psychiatry. 164 (3): 437–41. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.164.3.437. PMID 17329468.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Lam et al., 1999; Johnson & Leahy, 2004; Basco & Rush, 2005; Miklowitz & Goldstein, 1997; Frank, 2005.

- ^ Zaretsky AE, Rizvi S, Parikh SV (January 2007). "How well do psychosocial interventions work in bipolar disorder?". Can J Psychiatry. 52 (1): 14–21. PMID 17444074.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Havens LL, Ghaemi SN (2005). "Existential despair and bipolar disorder: the therapeutic alliance as a mood stabilizer". American journal of psychotherapy. 59 (2): 137–47. PMID 16170918.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - ^ Geddes JR, Burgess S, Hawton K, Jamison K, Goodwin GM (2004). "Long-term lithium therapy for bipolar disorder: systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials". Am J Psychiatry. 161 (2): 217–22. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.161.2.217. PMID 14754766.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Bauer MS, Mitchner L (2004). "What is a "mood stabilizer"? An evidence-based response". Am J Psychiatry. 161 (1): 3–18. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.161.1.3. PMID 14702242.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Cipriani, A (2005 Oct). "Lithium in the prevention of suicidal behavior and all-cause mortality in patients with mood disorders: a systematic review of randomized trials". The American journal of psychiatry. 162 (10): 1805–19. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.162.10.1805. PMID 16199826.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Poolsup N, Li Wan Po A, de Oliveira IR (2000). "Systematic overview of lithium treatment in acute mania". J Clin Pharm Ther. 25 (2): 139–156. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2710.2000.00278.x. PMID 10849192.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Macritchie K, Geddes JR, Scott J, Haslam D, de Lima M, Goodwin G (2002). Reid, Keith (ed.). "Valproate for acute mood episodes in bipolar disorder". Cochrane Database Syst Rev (2): CD004052. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD004052. PMID 12535506.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Calabrese JR, Bowden CL, Sachs GS, Ascher JA, Monaghan E, Rudd GD (1999). "A double-blind placebo-controlled study of lamotrigine monotherapy in outpatients with bipolar I depression. Lamictal 602 Study Group". J Clin Psychiatry. 60 (2): 79–88. doi:10.4088/JCP.v60n0203. PMID 10084633.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Barker, P., ed. (2003). Psychiatric and mental health nursing: the craft and caring. London: Arnold. pp. 284–5.

- ^ a b El-Mallakh, RS (2010 Jul). "Bipolar disorder: an update". Postgraduate medicine. 122 (4): 24–31. doi:10.3810/pgm.2010.07.2172. PMID 20675968.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Montgomery P, Richardson AJ (2008). Montgomery, Paul (ed.). "Omega-3 fatty acids for bipolar disorder". Cochrane Database Syst Rev (2): CD005169. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD005169.pub2. PMID 18425912.

- ^ Vasudev K, Macritchie K, Geddes J, Watson S, Young A (2006). Young, Allan H (ed.). "Topiramate for acute affective episodes in bipolar disorder". Cochrane Database Syst Rev (1): CD003384. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD003384.pub2. PMID 16437453.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Bergen M (1999). Riding the Roller Coaster: Living with Mood Disorders. Wood Lake Publishing Inc. ISBN 9781896836317.

- ^ "Introduction". cs.umd.edu. Retrieved February 16, 2008.

- ^ Judd LL, Akiskal HS, Schettler PJ, Endicott J, Leon AC, Solomon DA, Coryell W, Maser JD, Keller MB (December 2005). "Psychosocial disability in the course of bipolar I and II disorders: a prospective, comparative, longitudinal study". Arch Gen Psychiatry. 62 (12): 1322–30. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.62.12.1322. PMID 16330720.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: year (link) - ^ Ösby, U; Brandt, L; Correia, N; Ekbom, A; Sparén, P (2001). "Excess Mortality in Bipolar and Unipolar Disorder in Sweden". Arch Gen Psychiatry. 58 (9): 844–850. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.58.9.844. PMID 11545667.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - ^ Tohen M, Zarate CA Jr, Hennen J, Khalsa HM, Strakowski SM, Gebre-Medhin P, Salvatore P, Baldessarini RJ (December 2003). "The McLean-Harvard First-Episode Mania Study: prediction of recovery and first recurrence". Am J Psychiatry. 160 (12): 2099–107. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.160.12.2099. PMID 14638578.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Jackson A, Cavanagh J, Scott J (2003). "A systematic review of manic and depressive prodromes". J Affect Disord. 74 (3): 209–17. doi:10.1016/S0165-0327(02)00266-5. PMID 12738039.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Lam D, Wong G (2005). "Prodromes, coping strategies and psychological interventions in bipolar disorders". Clin Psychol Rev. 25 (8): 1028–42. doi:10.1016/j.cpr.2005.06.005. PMID 16125292.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Novick DM, Swartz HA, Frank E (2010). "Suicide attempts in bipolar I and bipolar II disorder: a review and meta-analysis of the evidence". Bipolar Disord. 12 (1): 1–9. doi:10.1111/j.1399-5618.2009.00786.x. PMID 20148862.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Benjamin J. Sadock, Harold I. Kaplan, Virginia A. Sadock (2007). Kaplan & Sadock's synopsis of psychiatry: behavioral sciences/clinical ... p. 388. ISBN 9780781773270. Retrieved 2010-12-30.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Roger S. McIntyre, MD, Joanna K. Soczynska, and Jakub Konarski. "Bipolar Disorder: Defining Remission and Selecting Treatment". Psychiatric Times, October 2006, Vol. XXIII, No. 11.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Ketter TA (2010). "Diagnostic features, prevalence, and impact of bipolar disorder". J Clin Psychiatry. 71 (6): e14. doi:10.4088/JCP.8125tx11c. PMID 20573324.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Soldani, Federico; Sullivan, PF; Pedersen, NL (2005). "Mania in the Swedish Twin Registry: criterion validity and prevalence". Australian and New Zealand of Psychiatry. 39 (4): 235–43. doi:10.1111/j.1440-1614.2005.01559.x. PMID 15777359.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Frederick K Goodwin and Kay R Jamison.Manic-Depressive Illness Chapter 7, "Epidemiology". Oxford University Press, 1990. ISBN 0-19-503934-3.

- ^ Judd, Lewis L.; Akiskal, HS (2003). "The prevalence and disability of bipolar spectrum disorders in the US population: re-analysis of the ECA database taking into account subthreshold cases". Journal of Affective Disorders. 73 (1–2): 123–31. doi:10.1016/S0165-0327(02)00332-4. PMID 12507745.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Merikangas KR, Akiskal HS, Angst J, Greenberg PE, Hirschfeld RM, Petukhova M, Kessler RC (May 2007). "Lifetime and 12-month prevalence of bipolar spectrum disorder in the National Comorbidity Survey replication". Arch Gen Psychiatry. 64 (5): 543–52. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.64.5.543. PMC 1931566. PMID 17485606.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Phelps J (2006). "Bipolar Disorder: Particle or Wave? DSM Categories or Spectrum Dimensions?". Psychiatric Times.

- ^ Christie KA, Burke JD Jr, Regier DA, Rae DS, Boyd JH, Locke BZ (1988). "Epidemiologic evidence for early onset of mental disorders and higher risk of drug abuse in young adults". Am J Psychiatry. 145 (8): 971–5. PMID 3394882. Retrieved July 1, 2007.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Goodwin & Jamison. p. 121.

- ^ Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 21188315, please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid=21188315instead. - ^ Liddell, Henry George and Robert Scott (1980). A Greek-English Lexicon (Abridged Edition). United Kingdom: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-910207-4.

- ^ "Circular insanity, 150 years on". Retrieved 2008-04-12.

- ^ Millon, Theordore (1996). Disorders of Personality: DSM-IV-TM and Beyond. New York: John Wiley and Sons. p. 290. ISBN 0-471-01186-X.

- ^ Kraepelin, Emil (1921) Manic-depressive Insanity and Paranoia ISBN 0-405-07441-7

- ^ Goodwin & Jamison. pp. 60–61.

- ^ Goodwin & Jamison. p62

- ^ Jamison, Kay Redfield (1995). An Unquiet Mind: A Memoir of Moods and Madness. New York: Knopf. ISBN 0-330-34651-2.

- ^ Jamison, Kay Redfield (1996). Touched With Fire: Manic-Depressive Illness and the Artistic Temperament. New York: The Free Press: Macmillian, Inc. ISBN 0-684-83183-X.

- ^ Robinson DJ (2003). Reel Psychiatry:Movie Portrayals of Psychiatric Conditions. Port Huron, Michigan: Rapid Psychler Press. pp. 78–81. ISBN 1-894328-07-8.

- ^ Robinson (Reel Psychiatry:Movie Portrayals of Psychiatric Conditions), p. 84–85

- ^ "The Secret Life of the Manic Depressive". BBC. 2006. Retrieved February 20, 2007.

- ^ "Child and Adolescent Bipolar Foundation special 90210 website". CABF. 2009. Retrieved April 7, 2009.[dead link]

- ^ "EastEnders' Stacey faces bipolar disorder". BBC Press Office. May 14, 2009. Retrieved May 28, 2009.

- ^ a b Tinniswood, Rachael (May 14, 2003). "The Brookie boys who shone at soap awards show". Liverpool Echo. Mirror Group Newspapers.

- ^ a b c d e f g h McClellan J, Kowatch R, Findling RL (2007). "Practice parameter for the assessment and treatment of children and adolescents with bipolar disorder". J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 46 (1): 107–25. doi:10.1097/01.chi.0000242240.69678.c4. PMID 17195735.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Anthony, James; Scott, Peter (1960). "Manic-depressive psychosis in childhood". J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 1: 53–72. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7610.1960.tb01979.x.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n Leibenluft E, Rich BA (2008). "Pediatric bipolar disorder". Annu Rev Clin Psychol. 4: 163–87. doi:10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.4.022007.141216. PMID 17716034.

- ^ http://www.dsm5.org/Proposed%20Revision%20Attachments/Justification%20for%20Temper%20Dysregulation%20Disorder%20with%20Dysphoria.pdf

- ^ http://www.dsm5.org/Newsroom/Documents/Diag%20%20Criteria%20General%20FINAL%202.05.pdf

- ^ Depp CA, Jeste DV (2004). "Bipolar disorder in older adults: a critical review". Bipolar Disord. 6 (5): 343–67. doi:10.1111/j.1399-5618.2004.00139.x. PMID 15383127.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Trinh NH, Forester B (2007). "Bipolar Disorder in the Elderly: Differential Diagnosis and Treatment". Psychiatric Times. 24 (14).

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

Cited texts

- Goodwin FK, Jamison KR (1990). Manic-Depressive Illness. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-503934-3.

- Goodwin FK, Jamison KR (2007). Manic-Depressive Illness: Bipolar Disorders and Recurrent Depression, 2nd Edition. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-513579-2.

Further reading

- Contemporary first-person accounts

- Simon, Lizzie. 2002. Detour: My Bipolar Road Trip in 4-D. New York: Simon and Schuster. ISBN 0-7434-4659-3.

- Behrman, Andy. 2002. Electroboy: A Memoir of Mania. New York: Random House. ISBN 0-375-50358-7.

- Hornbacher, Marya. 2008. Madness: A Bipolar Life. ISBN 978-0618754458.

- Lovelace, David. 2008. Scattershot: My Bipolar Family. New York: Dutton Adult. ISBN 0-525-95078-8.

- Managing bipolar disorder

- Berk, Lesley (March 5, 2009). Living with Bipolar. Vermilion. ISBN 9780091924256.

- Bipolar disorder in children

- Greenberg, Rosalie. 2008. Bipolar Kids: Helping Your Child Find Calm in the Mood Storm. ISBN 978-0-7382-1113-8

- Papolos, Demetri, and Papolos, Janice. 2007. The Bipolar Child: The Definitive and Reassuring Guide to Childhood's Most Misunderstood Disorder -- Third Edition. ISBN 978-0-7679-2860-1

- Raeburn, Paul. 2004. Acquainted with the Night: A Parent's Quest to Understand Depression and Bipolar Disorder in His Children.

- Earley, Pete. Crazy. 2006. New York: G. P. Putnam's Sons. ISBN 0-399-15313-6. A father's account of his son's bipolar disorder.

- Classic works on bipolar disorder

- Kraepelin, Emil. 1921. Manic-depressive Insanity and Paranoia ISBN 0-405-07441-7 (English translation of the original German from the earlier eighth edition of Kraepelin's textbook — now outdated, but a work of major historical importance).

- Mind Over Mood: Cognitive Treatment Therapy Manual for Clients by Christine Padesky, Dennis Greenberger. ISBN 0-89862-128-3

External links

- Bipolar Disorder overview from the U.S. National Institute of Mental Health website

- NICE Bipolar Disorder clinical guidelines from the U.K. National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence website

- Template:Dmoz