V. S. Ramachandran

Vilayanur S. Ramachandran | |

|---|---|

Ramachandran at the 2011 Time 100 gala | |

| Born | |

| Alma mater | M.B.B.S. at Stanley Medical College, Chennai; Ph.D. from the University of Cambridge |

| Known for | Neurology, visual perception, phantom limbs, synesthesia, autism, body integrity identity disorder |

| Awards | Ariens Kappers Medal from the Royal Netherlands Academy of Sciences; The Padma Bhushan from the President of India; BBC Reith Lectures, 2003; elected to a visiting fellowship at All Souls College, Oxford; co-winner of the 2005 Henry Dale Prize awarded by the Royal Institution of Great Britain. |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Neurology, Psychology |

| Institutions | University of California, San Diego (professor) and Center for Brain and Cognition (director) |

| Doctoral advisors | Oliver Braddick, David Whitteridge, FW Campbell, H Barlow |

Vilayanur Subramanian "Rama" Ramachandran, born 1951, is a neuroscientist known for his work in the fields of behavioral neurology and visual psychophysics. He is the Director of the Center for Brain and Cognition,[1][2][3] and is currently a Professor in the Department of Psychology[4] and the Neurosciences Graduate Program[5] at the University of California, San Diego.

Ramachandran is noted for his use of experimental methods that rely relatively little on complex technologies such as neuroimaging. According to Ramachandran, "too much of the Victorian sense of adventure [in science] has been lost."[6] Despite the apparent simplicity of his approach, Ramachandran has generated many new ideas about the brain.[7] He has been called "The Marco Polo of neuroscience" by Richard Dawkins and "the modern Paul Broca" by Eric Kandel.[8] In 1997 Newsweek named him a member of "The Century Club", one of the "hundred most prominent people to watch" in the 21st century.[9] In 2011 Time listed him as one of "the most influential people in the world" on the "Time 100" list.[10][11]

Early life and education

Vilayanur Subramanian Ramachandran (in accordance with Indian family name traditions, his family name, Vilayanur, is placed first) was born in 1951 in Tamil Nadu, India. In Tamil, one of the classical languages of India, his name is written as விளையனூர் இராமச்சந்திரன். His father, V.M. Subramanian, was an engineer who worked for the UN Industrial Development Organization and served as a diplomat in Thailand and Bangkok.[12] Ramachandran spent much of his youth moving among several different posts in India and other parts of Asia.[13][14] As a young man he attended schools in Madras, Bangkok and England,[15] and pursued many scientific interests, including conchology.[13] Ramachandran obtained an M.B.B.S. from Stanley Medical College in Madras, India, and subsequently obtained a Ph.D. from Trinity College at the University of Cambridge. While a graduate student at Cambridge Ramachandran also collaborated on research projects with faculty at Oxford, including David Whitteridge of the Physiology Department. He then spent two years at Caltech, as a research fellow working with Jack Pettigrew. He was appointed Assistant Professor of Psychology at the University of California, San Diego in 1983, and has been a full professor there since 1998.

Ramachandran is the grandson of Sir Alladi Krishnaswamy Iyer, Advocate General of Madras and co-architect of the Constitution of India.[14][16] He is married to Diane Rogers-Ramachandran and they have two boys, Mani and Jaya[13]

Scientific career

Ramachandran has studied neurological syndromes to investigate neural mechanisms underlying human mental function. Ramachandran is best known for his work on syndromes such as phantom limbs, body integrity identity disorder, and Capgras delusion. His research has also contributed to the understanding of synesthesia.[10][13] More recently his work has focused on the theoretical implications of mirror neurons and the cause of autism. In addition, Ramachandran is known for the invention of the mirror box. He has published over 180 papers in scientific journals. Twenty of these have appeared in Nature, and others have appeared in Science, Nature Neuroscience, Perception and Vision Research. Ramachandran is a member of the editorial board of Medical Hypotheses (Elsevier) and has published 15 articles there.[17]

Ramachandran's work in behavioral neurology has been widely reported by the media. He has appeared in numerous Channel 4 and PBS documentaries. He has also been featured by the BBC, the Science Channel, Newsweek, Radio Lab, and This American Life, TED Talks, and Charlie Rose.

He is author of Phantoms in the Brain which formed the basis for a two part series on BBC Channel 4 TV (UK) and a 1-hour PBS special in the USA. He is the editor of the Encyclopedia of the Human Brain (2002), and is co-author of the bi-monthly "Illusions" column in Scientific American Mind.

Ramachandran has recently lamented that science has become too professionalized. In a 2010 interview with the British Neuroscience Association he stated: "But where I'd really like to go is back in time. I'd go to the Victorian age, before science had professionalized and become just another 9–5 job, with power-brokering and grants nightmares. Back then scientists just had fun. People like Darwin and Huxley; the whole world was their playground."[18]

Human vision

Ramachandran’s early research was on human visual perception using psychophysical methods to draw clear inferences about the brain mechanisms underlying visual processing.

Ramachandran is credited with discovering several new visual effects and illusions; most notably perceived slowing of motion at equiluminance (when red and green are seen as equally bright), stereoscopic "capture" using illusory contours, stereoscopic learning, shape-from-shading, and motion capture. He invented (together with Richard Gregory) filling in of "artificial scotomas" and discovered a new "dynamic noise after effect." He also invented a class of stimuli (phantom contours) that selectively activate the magnocellular pathway in human vision and that have been used by Anne Sperling, and her colleagues, to evaluate aspects of dyslexia.[19]

Phantom limbs

When an arm or leg is amputated, patients continue to feel vividly the presence of the missing limb as a "phantom limb". Building on earlier work by Ronald Melzack (McGill University) and Timothy Pons (NIMH), Ramachandran theorized that there was a link between the phenomenon of phantom limbs and neural plasticity in the adult human brain. In particular, he theorized that the body image maps in the somatosensory cortex are re-mapped after the amputation of a limb. In 1993, working with T.T. Yang who was conducting MEG research at the Scripps Research Institute,[20] Ramachandran demonstrated that there had been measurable changes in the somatosensory cortex of several patients who had undergone arm amputations.[21][22] Ramachandran theorized that there was a relationship between the cortical reorganization evident in the MEG images and the referred sensations he observed in his subjects. He presented this theory in a paper titled "Perceptual correlates of massive cortical reorganization."[23] Although Ramachandran was one of the first scientists to emphasize the role of cortical reorganization as the basis for phantom limb sensations, subsequent research has demonstrated that referred sensations are not the perceptual correlate of cortical reorganization after amputation.[24] The question of which neural processes are related to non-painful referred sensations has not been resolved.

Mirror visual feedback

Ramachandran is credited with the invention of the mirror box and the introduction of Mirror Visual Feedback (MVF) as a treatment for a variety of conditions. Most patients with phantom arms feel that they can move their phantoms; however for many the phantom is fixed or "paralyzed", often in a cramped position that is excruciatingly painful. Ramachandran created the mirror box in which a mirror is placed vertically in front of the patient and had patients look at the mirror reflection of the normal arm so that the reflection was optically superimposed on the felt location of the phantom (thus creating the visual illusion that the phantom had been resurrected). Moving the intact limb creates the illusion that the phantom limb is moving, and over time this illusion reduces the pain experienced by the patient. Several research studies using mirror therapy have produced promising results.[25][26]

Ramachandran has also suggested that mirror visual feedback (MVF) may help accelerate recovery of arm (and leg) function after paralysis from stroke. In 1998 Ramachandran (and his colleague Eric Altschuler) tested MVF on nine patients with stroke. They found their results encouraging but stated that larger studies were needed to evaluate the effectiveness of this therapy.[27] More recently MVF has also been shown to promote recovery from complex regional pain syndrome in patients who have acute, early symptoms.[28] For patients who suffer from chronic regional pain syndrome (CRPS1) mirror therapy can produce higher levels of pain and is not used as an initial therapy.[29]

Synesthesia

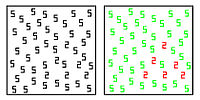

Ramachandran has studied the neural mechanisms of synesthesia, a condition in which stimulation in one sensory modality leads to experiences in a second, unstimulated modality. His initial studies focused on grapheme → color synesthesia, in which viewing black and white letters or numbers (collectively referred to as graphemes) on a page evokes the experience of seeing colors. Ramachandran (with then PhD student, Edward Hubbard) showed that some synesthetes were better able to detect "embedded figures" composed of one letter or number (for example a triangle composed of 2s) on a background of another number (for example 5s).[30][31]

Based on his previous work on phantom limbs, Ramachandran suggested that synesthesia may arise from a cross-activation between brain regions.[30] Although the idea of cross-connections dates to some of the earliest work on synesthesia,[32] Ramachandran was the first to give this idea a specific anatomical explanation. Ramachandran suggested that grapheme-color synesthesia is the result of increased connectivity between brain areas that are responsible for the perceptual recognition of letters and numbers and colors, perhaps due to genetic factors, given that synesthesia is known to run in families.[30] Consistent with this model, Ramachandran's group found increased activity in color selective areas in synesthetes compared to non-synesthetes using fMRI.[31][33] Using MEG, they also showed that differences between synesthetes and non-synesthetes begin very quickly after the grapheme is presented.[34]

More recently, Ramachandran has also begun investigations of other forms of synesthesia, including number forms[35][36] and tactile → emotion synesthesia.[37]

Additionally, Ramachandran has suggested that synesthesia and conceptual metaphor may share a common basis in cortical cross-activation. This suggestion focuses on the importance of the angular gyrus for multimodal integration and metaphor production. Following Lakoff and Johnson,[38] Ramachandran argues that metaphors are non-arbitrary. Ramachandran and Hubbard suggest that "these rules [of metaphor production] are a result of strong anatomical constraints that permit certain types of cross-activation, but not others."[30]p. 18 Ramachandran has suggested that the evolution of language is the result of three types of non-arbitrary mappings, 1) between sounds and visual shapes (the bouba-kiki effect), 2) sensory-to-motor synesthesia and 3) motor-to-motor synesthesia (or "synkinesia").[30]p. 18-23

Ramachandran has helped to advance public awareness of synesthesia by hosting two meetings of the American Synesthesia Association at UCSD in 2002[39] and 2011.[40]

Mirror neurons

Ramachandran is known for advocating the importance of mirror neurons. Ramachandran has stated that the discovery of mirror neurons is the most important unreported story of the last decade.[41] (Mirror neurons were first reported in a paper published in 1992 by a team of researchers led by Giacomo Rizzolatti at the University of Parma.[42]) Ramachandran has speculated that research into the role of mirror neurons will help explain a variety of human mental capacities ranging from empathy, imitation learning, and the evolution of language. Ramachandran has also theorized that mirror neurons may be the key to understanding the neurological basis of human self awareness.[43][44]

Ramchandran has theorized that in addition to motor command mirror neurons there are mirror neurons that are activated when a person observes someone else being touched. In 2008 Ramachandran conducted an experiment in which several phantom arm patients reported feeling touch signals on their phantom arms when they observed the arm of a student being touched. In a 2009 discussion of this theory Ramachandran and Althschuler called these mirror neurons "touch mirror neurons."[45]

Theories of autism

In 1999, Ramachandran, in collaboration with then post-doctoral fellow Eric Altschuler and colleague Jaime Pineda, was one of the first to suggest that a loss of mirror neurons might be the key deficit that explains many of the symptoms and signs of autism spectrum disorders.[46] Between 2000 and 2006 Ramachandran and his colleagues at UC San Diego published a number of articles in support of this theory, which became known as the "Broken Mirrors" theory of autism.[47][48][49] Ramachandran and his colleagues did not measure mirror neuron activity directly; rather they demonstrated that children with ASD showed abnormal EEG responses (known as Mu wave suppression) when they observed the activities of other people. In 2008 Oberman, Ramachandran and Pineda conducted an experiment in which children with ASD showed both normal and abnormal EEG responses depending on their familiarity with people whose actions they were observing.[50] Oberman and Ramachanran concluded that "The study revealed that mu suppression was sensitive to degree of familiarity. Both typically developing participants and those with ASD showed greater suppression to familiar hands compared to those of strangers. These findings suggest that the Mirror Neuron Systmen responds to observed actions in individuals with ASD, but only when individuals can identify in some personal way with the stimuli."[51]

Ramachandran's theory that dysfunctional mirror neuron systems(MNS) play an important role in autism remains controversial. In his 2011 review of The Tell-Tale Brain, Simon Baron-Cohen, Director of the Autism Research Center at Cambridge University, states that "As an explanation of autism, the [Broken Mirrors] theory offers some tantalizing clues; however, some problematic counter-evidence challenges the theory and particularly its scope."[52]

Recognizing that dysfunctional mirror neuron systems cannot account for the wide range of symptoms that are included in autism spectrum disorder (ASD), Ramachandran has theorized that childhood temporal lobe epilepsy and olfactory bulb dysgenesis may also play a role in creating the symptoms of ASD. In 2010 Ramachandran stated that "The olfactory bulb hypothesis has important clinical implications" and announced that his group would undertake a study "comparing olfactory bulb volumes in individuals with autism with those of normal controls."[53]

Rare neurological syndromes: Apotemnophilia & Capgras Delusion

In 2008 Ramachandran, along with David Brang and Paul McGeoch, published the first paper to theorize that apotemnophilia is a neurological disorder caused by damage to the right parietal lobe of the brain.[54] This rare disorder, in which a person desires the amputation of a limb, was first identified by John Money in 1977. Building on Ramachandran's previous work identifying representations of body image in the brain, they argued that this disorder stems from a neural body image that is incomplete. Hence the person sees their limb as a foreign appendage that is outside their body.[54] Ramachandran has extended this theory to suggest that anorexia nervosa may be a body image disorder that has its basis in neurological representations of the body, rather than an appetite disorder of the hypothalamus.[55]

In collaboration with then post-doctoral fellow, William Hirstein, Ramachandran published a paper in 1997 in which he presented a theory describing the neural basis of Capgras delusion, a delusion in which family members and other loved ones are thought to be replaced by impostors. Previously, Capgras delusion was attributed to a disconnection between facial recognition and emotional arousal.[56] Ramachandran and Hirstein presented a more specific structural explanation that argued that Capgras delusion might be the result of a disconnection between the "fusiform face area", a region of the fusiform gyrus involved in face perception, and the amygdala, which is involved in the emotional responses to familiar faces. Additionally, based on their model and the specific responses of the patient they examined (a Brazilian man who had sustained a head injury in a traffic accident), Ramachandran and Hirstein proposed a general theory of memory formation. They speculated that a person suffering from Capgras delusion loses the ability to form a taxonomy of memories and hence they can no longer manage memories effectively. Instead of a continuum of memories that constitute a unified sense of self, each memory takes on its own categorical sense of self.[57]

Awards and honors

Ramachandran was elected to a visiting fellowship at All Souls College, Oxford (1998–1999). In addition he was a Hilgard visiting professor at Stanford University in 2005. He has received honorary doctorates from Connecticut College (2001) and the Indian Institute of Technology, Madras (2004).[58] Ramachandran received the annual Ramon y Cajal award (2004) from the International Neuropsychiatry Society, and the Ariens-Kappers medal from the Royal Netherlands Academy of Sciences for his contributions to Neuroscience (1999). He shared the 2005 Henry Dale Prize with Michael Brady of Oxford, and, as part of the award was elected an honorary life member of the Royal institution for "outstanding research of an interdisciplinary nature".[59] In 2007, the President of India conferred on him the third highest civilian award and honorific title in India, the Padma Bhushan.[60] In 2008, he was listed as number 50 in the Top 100 Public Intellectuals Poll.[61]

Invited plenary lectures

Ramachandran has presented numerous plenary lectures around the world. He gave the Decade of the Brain lecture at the 25th annual meeting of the Society for Neuroscience in 1995,[62] the D.O. Hebb Lecture in 1997 (McGill University),[63] and the Keynote Lecture at the 1999 Decade of the Brain meeting before the NIH and the Library of Congress,[64][65] as well as the Rabindranath Tagore lecture at the Centre for Philosophy and Foundations of Science in New Delhi.[66] In 2003 he gave the annual BBC Reith Lectures.[67] In 2007 he gave a public lecture that was part of a series sponsored by the Templeton Foundation at the Royal Society in London.[68] He gave the 2010 IAS Distinguished Lecture at the University of Bristol's Institute of Advanced Studies dedicated to the memory of his longtime friend and collaborator, Richard Gregory.[69] In October 2011, Ramachandran delivered a lecture titled "The Neurology of Human Nature" at the 47th Nobel Conference at Gustavus Adolphus College in Saint Peter, Minnesota.[70] In 2012, he will give the Gifford Lectures (May 28, 2012 - May 30, 2012) at the University of Glasgow.[71]

Testimony as an expert witness

Ramachandran has served as an expert witness on the delusions associated with pseudocyesis (false pregnancy). At the 2007 trial of Lisa M. Montgomery he testified that Montgomery suffered from severe pseudocyesis disorder and that she was unable to appreciate the nature and quality of her acts.[72][73]

Minotaurasaurus ramachandrani

An interest in paleontology led him to purchase a fossil dinosaur skull from the Gobi desert, which was named after him as Minotaurasaurus ramachandrani in 2009.[74] A controversy has surfaced around the provenance of this skull. Some paleontologists claim that this fossil was removed from the Gobi desert without the permission of the Chinese government and sold without proper documentation. V.S. Ramachandran, who purchased the fossil in Tucson, Arizona, says that he would be happy to repatriate the fossil to the appropriate nation, if someone shows him "evidence it was exported without permit". For now, the specimen rests at the Victor Valley Museum, an hour's drive east of Los Angeles.[75]

Books authored

- Phantoms in the Brain : Probing the Mysteries of the Human Mind, coauthor Sandra Blakeslee, 1998, ISBN 0-688-17217-2

- The Encyclopedia of the Human Brain (editor-in-chief) ISBN 0-12-227210-2

- The Emerging Mind, 2003, ISBN 1-86197-303-9

- A Brief Tour of Human Consciousness: From Impostor Poodles to Purple Numbers, 2005, ISBN 0-13-187278-8 (paperback edition)

- The Tell-Tale Brain: A Neuroscientist's Quest for What Makes Us Human, 2010, ISBN 978-0-393-07782-7

See also

References

- ^ Center for Brain and Cognition website

- ^ Ramachandran Bio on CBC website

- ^ Psychology Department Webage with link to CBC

- ^ UCSD Psychology Faculty Directory

- ^ Ramachandran Neurosciences Graduate Program Webpage

- ^ This Week @ UCSD, April 25, 2011

- ^ Anthony, VS Ramachandran: The Marco Polo of neuroscience, The Observer, January 29, 2011.

- ^ A Brief Tour of Human Consciousness, 2004, Back Cover

- ^ "The Century Club". Newsweek. April 21, 1997. Retrieved February 16, 2011.

- ^ a b "V.S. Ramachandran - Time 100". April 21, 2011. Retrieved April 21, 2011. The citation by Tom Insel, Director of NIH, reads: "Once described as the Marco Polo of neuroscience, V.S. Ramachandran has mapped some of the most mysterious regions of the mind. He has studied visual perception and a range of conditions, from synesthesia to autism. V.S. Ramachandran is changing how our brains think about our minds."

- ^ In public polling of the people included in the 2011 list, Ramachandran ranked 97 out of 100.[1]

- ^ The Science Studio Interview, June 10, 2006, transcript

- ^ a b c d Colapinto, J (May 11, 2009). "Brain Games; The Marco Polo of Neuroscience". The New Yorker. Retrieved March 11, 2011. Full text via Lexis-Nexus here

- ^ a b Andrew Anthony. date = January 30, 2011 "VS Ramachandran: The Marco Polo of neuroscience". guardian.co.uk. Retrieved August 8, 2011.

{{cite web}}: Check|url=value (help); Missing pipe in:|url=(help) - ^ Transcript, The Science Studio

- ^ Ravi, Y.V. (2003-09-23). "Legal luminary". The Hindu. Retrieved 2011-04-21.

- ^ ScienceInsider, March 8, 2010

- ^ Bulletin, BNA, page 14, issue 62, Autumn 2010

- ^ Sperling et al., Selective magnocellular deficits in dyslexia: a "phantom contour" study, Neuropsychologia, 41,(2003)1422-1429

- ^ Yang, UCSD Faculty web page

- ^ Yang TT, Gallen CC, Ramachandran VS, Cobb S, Schwartz BJ, Bloom FE (1994). "Noninvasive detection of cerebral plasticity in adult human somatosensory cortex". Neuroreport. 5 (6): 701–4. doi:10.1097/00001756-199402000-00010. PMID 8199341.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ For a competing view, see: Flor et al., Nature Reviews, Vol 7, November 2006 [2]

- ^ Ramachandran, Rogers-Ramachandran, Stewart, Perceptual correlates of massive cortical reorganization, Science, 1992, Nov 13, 1159-1160

- ^ Reprogramming the cerebral cortex: plasticity following central and peripheral lesions, Oxford, 2006, Edited by Stephen Lomber, pages 334

- ^ Ramachandran VS, Rogers-Ramachandran D (1996). "Synaesthesia in phantom limbs induced with mirrors". Proc. Biol. Sci. 263 (1369): 377–86. doi:10.1098/rspb.1996.0058. PMID 8637922. Retrieved 2008-09-23.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ DOD Live web site,Feb 28, 2011

- ^ Altschuler et al, Research Letter, Lancet, Vol 353, June 12, 1999

- ^ McCabe CS, Haigh RC, Blake DR (2008). "Mirror visual feedback for the treatment of complex regional pain syndrome (type 1)". Curr Pain Headache Rep. 12 (2): 103–7. doi:10.1007/s11916-008-0020-7. PMID 18474189.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Moseley,G.L., Graded motor imagery is effective for long-standing complex regional pain syndrome: a randomised controlled trial, Pain, 108,(2004)192-198 [3]

- ^ a b c d e Ramachandran VS and Hubbard EM (2001). "Synaesthesia: A window into perception, thought and language" (PDF). Journal of Consciousness Studies. 8 (12): 3–34.

{{cite journal}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|month=(help) - ^ a b Hubbard EM, Arman AC, Ramachandran VS, Boynton GM (2005). "Individual differences among grapheme-color synesthetes: brain-behavior correlations" (PDF). Neuron. 45 (6): 975–85. doi:10.1016/j.neuron.2005.02.008. PMID 15797557. Retrieved 2011-04-21.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Flournoy, T (1893). Des Phenomenes de Synopsie [On the Phenomena of Synopsia]. Genevea, Switzerland: Charles Eiggenman & Sons.

- ^ Hubbard EM, Ramachandran VS (2005). "Neurocognitive mechanisms of synesthesia" (PDF). Neuron. 48 (3): 509–520. doi:10.1016/j.neuron.2005.10.012. PMID 16269367.

- ^ Brang D, Hubbard EM, Coulson S, Huang M, Ramachandran VS (2010). "Magnetoencephalography reveals early activation of V4 in grapheme-color synesthesia". Neuroimage. 53 (1): 268–274. doi:10.1016/j.neuroimage.2010.06.00. PMID 20547226.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Brang D, Teuscher U, Ramachandran VS, Coulson S. (2010). "Temporal sequences, synesthetic mappings, and cultural biases: the geography of time". Consciousness and Cognition. 19 (1): 311–320. doi:10.1016/j.concog.2010.01.003. PMID 20117949.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Teuscher U, Brang D, Ramachandran VS, Coulson S. (2010). "Spatial cueing in time-space synesthetes: An event-related brain potential study". Brain and Cognition. 74 (1): 35–46. doi:10.1016/j.bandc.2010.06.001. PMID 20637536.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Ramachandran VS, Brang D. (2008). "Tactile-emotion synesthesia". Neurocase. 14 (5): 390–399. doi:10.1080/13554790802363746. PMID 18821168.

- ^ Lakoff, G & Johnson, M (1980). Metaphors We Live By. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "UCSD ASA Program". American Synesthesia Association. Retrieved June 6, 2011.

- ^ "ASA main page". American Synesthesia Association. Retrieved June 6, 2011.

- ^ Ramachandran, V.S. (June 1, 2000). "Mirror neurons and imitation learning as the driving force behind "the great leap forward" in human evolution". Edge Foundation web site. Retrieved October 19, 2011.

- ^ Rizzolatti,G.,Fabbri-Destro,M,"Mirror Neurons:From Discovery to Autism" Experimental Brain Research, (2010)200:223–237 [4]

- ^ Oberman, L.M. & Ramachandran, V.S. (2008). "Reflections on the Mirror Neuron System: Their Evolutionary Functions Beyond Motor Representation". In Pineda, J. A. (ed.). Mirror Neuron Systems: The Role of Mirroring Processes in Social Cognition. Contemporary Neuroscience. Humana Press. pp. 39–62. ISBN 978-1934115343.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Ramachandran, V.S. (January 1, 2009). "Self Awareness: The Last Frontier". Edge Foundation web site. Retrieved October 19, 2011.

- ^ Ramachandran, Altschuler, The use of visual feedback, in particular mirror visual feedback, in restoring brain funciton, Brain, 2009, 132, 1693-1710 [5]

- ^ E.L. Altschuler, A. Vankov, E.M. Hubbard, E. Roberts, V.S. Ramachandran and J.A. Pineda (2000). "Mu wave blocking by observer of movement and its possible use as a tool to study theory of other minds". 30th Annual Meeting of the Society for Neuroscience. Society for Neuroscience.

{{cite conference}}: Unknown parameter|booktitle=ignored (|book-title=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Oberman LM, Hubbard EM, McCleery JP, Altschuler EL, Ramachandran VS & Pineda JA. (2005). "EEG evidence for mirror neuron dysfunction in autism spectrum disorders" (PDF). Cognitive Brain Research. 24 (2): 190–198. doi:10.1016/j.cogbrainres.2005.01.014. PMID 15993757.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Ramachandran, V.S. & Oberman, L.M. (October 16, 2006). "Broken Mirrors: A Theory of Autism" (PDF). Scientific American: 62–69. doi:10.1038/scientificamerican1106-62. PMID 17076085.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Oberman LM & Ramachandran VS. (2007). "The simulating social mind: the role of the mirror neuron system and simulation in the social and communicative deficits of autism spectrum disorders" (PDF). Psychological Bulletin. 133 (2): 310–327. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.133.2.310. PMID 17338602.

- ^ Oberman, LM Ramachandran, VS & Pineda, JA (2008). "Modulation of mu suppression in children with autism spectrum disorders in response to familiar or unfamiliar stimuli. The mirror neuron hypothesis" (PDF). Neuropsychologia. 46: 1558–1565.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Oberman,Ramachanran,Pineda,Modulation of mu suppression in children with autism spectrum disorders in response to familiar or unfamiliar stimuli: the mirror neuron hypothesis,Neuropsychologia,2008,April,46(5),1558-65 [6]

- ^ Baron-Cohen,Simon,"Making Sense of the Brain's Mysteries, American Scientist, On-line Book Review, July–August,2011 [7]

- ^ Brang,D, Ramachandran,VS, Olfactory bulb dysgenesis, mirror neuron system dysfunction, and autonomic dsyregulation as the neural basis for autism, Medical Hypotheses, 74, 2010, 919-921 [8]

- ^ a b Brang, D McGeoch, P & Ramachandran VS (2008). "Apotemnophilia: A Neurological Disorder" (PDF). Cognitive Neuroscience and Neuropsychology. 19: 1305–1306. doi:10.1097/WNR.0b013e32830abc4d. PMID 18695512.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Ramachandran VS, Brang D, McGeoch PD, Rosar W. (2009). "Sexual and food preference in apotemnophilia and anorexia: interactions between 'beliefs' and 'needs' regulated by two-way connections between body image and limbic structures" (PDF). Perception. 38 (5): 775–777. PMID 19662952.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Ellis MD, Young, Accounting for delusional misidentifications, British Journal of Psychiatry, Aug 1990, 239-248 [9]

- ^ Hirstein, W; Ramachandran, VS (1997). "Capgras syndrome: a novel probe for understanding the neural representation of the identity and familiarity of persons" (PDF). Proc Biol Sci., B. 264 (1380): 437–444. doi:10.1098/rspb.1997.0062. PMC 1688258. PMID 9107057.

- ^ Science Direct, 2 January 2007

- ^ [10]

- ^ Search on http://india.gov.in/myindia/advsearch_awards.php for Ramachandaran (sic!) in March 2008.

- ^ "Intellectuals". Prospect Magazine. 2009. Retrieved June 4, 2011.

- ^ Society for Neuroscience (1995). Society for Neuroscience Abstracts, Volume 21, Part 1. Society for Neuroscience. p. viii. ISBN 9780916110451.

- ^ McGill Psychology Department web site

- ^ "The Science of Cognition". Library of Congress. January 3, 2000. Retrieved October 4, 2011.

- ^ "NIH Record 11-02-99--Cognitive Science Advances Understanding of Brain, Experience". NIH. November 2, 1999. Retrieved October 4, 2011.

- ^ "Proceedings: Welcome to CPFS". Retrieved October 4, 2011.

- ^ "BBC - Radio 4 - Reith Lectures 2003 - The Emerging Mind". Retrieved October 4, 2011.

- ^ "Nature and nurture in brain function: clues from synesthesia and phantom limbs". November 28, 2007. Retrieved October 4, 2011.

- ^ "2010 IAS Distinguished Lecture: Neuroscience and Human Nature". University of Bristol. June 28, 2010. Retrieved June 4, 2011.

- ^ "Schedule, Nobel Conference 47". Gustavus Adolphus College. Retrieved October 4, 2011.

- ^ "Body And Mind: Insights From Neuroscience". Retrieved October 4, 2011.

- ^ Karen Olson (October 21, 2007). "Brain Expert Witness Testifies in Lisa Montgomery Trial". Expert Witness Blog, Juris Pro. Retrieved November 21, 2011.

- ^ "United States of America v. Lisa M. Montgomery". American Lawyer. April 7, 2011. Retrieved November 21, 2011.

- ^ Miles, Clifford A. and Clark J. Miles (2009). "Skull of Minotaurasaurus ramachandrani, a new Cretaceous ankylosaur from the Gobi Desert" (PDF). Current Science. 96 (1): 65–70.

- ^ naturenews, February 2, 2009

External links

- Vilayanur S. Ramachandran (official webpage)

- Take the Neuron Express for a Brief Tour of Consciousness The Science Network interview with V.S. Ramachandran

- Ramachandran Illusions

- All in the Mind interview

- Reith Lectures 2003 The Emerging Mind by Ramachandran

- TED talk by Ramachandran on brain damage and structures of the mind

- Talk at Princeton A 2009 talk about his work.

- The Third Culture Scroll down for three of his essays regarding mirror neurons and self-awareness

- Ramachandran's contribution to The Science Network's Beyond Belief 2007 Lectures on synaesthesia and metaphor.

- 1951 births

- Psychologists

- Neuroscientists

- Indian emigrants to the United States

- Cognitive neuroscientists

- Autism researchers

- Tamil Nadu scientists

- Living people

- American people of Indian descent

- Recipients of the Padma Bhushan

- Alumni of Trinity College, Cambridge

- Fellows of the Society of Experimental Psychologists

- University of California, San Diego faculty

- Stanford University staff

- Harvard University staff

- Columbia University staff

- Indian agnostics

- American agnostics