Harvard University

- "Harvard" redirects here. For other uses of the name Harvard, see Harvard (disambiguation).

| |

| Motto | Veritas (Truth) |

|---|---|

| Type | Private |

| Established | September 8, 1636 |

| Endowment | US$25.9 billion |

| President | Lawrence H. Summers (announced resignation effective June 30, 2006) |

| Undergraduates | 6,655 |

| Postgraduates | 13,000 |

| Location | , , |

| Campus | Urban, 380 acres/154 ha |

| Athletics | 41 varsity teams |

| Nickname | Crimson |

| Mascot | John Harvard File:Harvard university john mascot.jpg |

| Website | www.harvard.edu |

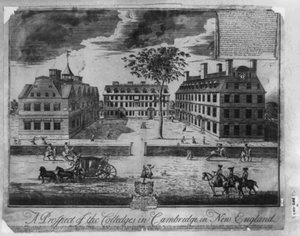

Harvard University (incorporated as The President and Fellows of Harvard College) is a private university in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Founded on September 8, 1636 by a vote of the Great and General Court of the Massachusetts Bay Colony, Harvard is the oldest institution of higher education in the United States and a member of the Ivy League.

The institution was named Harvard College on March 13, 1639, after its first principal donor, a young clergyman named John Harvard. A graduate of Emmanuel College, Cambridge, John Harvard bequeathed a few hundred books in his will to form the basis of the college library collection, along with several hundred pounds. The earliest known official reference to Harvard as a "university" rather than a "college" occurred in the new Massachusetts Constitution of 1780.

In his 1869-1909 tenure as Harvard president, Charles William Eliot radically transformed Harvard into the pattern of the modern research university. Eliot's reforms included elective courses, small classes, and entrance examinations. The Harvard model influenced American education nationally, at both college and secondary levels.

In 2000, Radcliffe College, initially founded as the "Harvard Annex" for women, merged formally with Harvard University, becoming the Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study.[1]

Harvard has the world's largest university library collection (third largest library overall after the British Library and the Library of Congress), and the largest financial endowment of any academic institution, standing at $25.9 billion as of 2005.

Institution

A faculty of about 2,300 professors serves about 6,650 undergraduate and 13,000 graduate students. The school color is crimson, which is also the name of the Harvard sports teams and the daily newspaper, The Harvard Crimson. The color was unofficially adopted (in preference to magenta) by an 1875 vote of the student body, although the association with some form of red can be traced back to 1858, when Charles William Eliot, a young graduate student who would later become Harvard's president, bought red bandannas for his crew so they could more easily be distinguished by spectators at a regatta.

Prominent student organizations at Harvard include the aforementioned Crimson; the Harvard Advocate, one of the nation's oldest literary magazines and the oldest current publication at Harvard; the Harvard Lampoon, a humor magazine; and the Hasty Pudding Theatricals, which produces an annual burlesque and celebrates notable actors at its Man of the Year and Woman of the Year ceremonies; and the Harvard Glee Club, the oldest college chorus in America. The Harvard-Radcliffe Orchestra, composed mainly of undergraduates, was founded in 1808 as the Pierian Sodality and has been performing as a symphony orchestra since the 1950s.

Harvard College has traditionally drawn many of its students from private schools, though today the majority of undergraduates come from public schools across the United States and around the globe.

Harvard has a rivalry with the Massachusetts Institute of Technology which dates back to 1900, when a merger of the two schools was frequently mooted and at one point officially agreed upon (ultimately canceled by Massachusetts courts). Today, the two schools cooperate as much as they compete, with many joint conferences and programs, including the Harvard-MIT Division of Health Sciences and Technology, the Harvard-MIT Data Center and the Dibner Institute for the History of Science and Technology. In addition, students at the two schools can cross-register in undergraduate classes without any additional fees, for credits toward their own school's degrees.

Over its history, Harvard has graduated many famous alumni, along with a few infamous ones. Among the best-known are political leaders John Hancock, John Adams, Theodore Roosevelt, Franklin Roosevelt and John F. Kennedy; philosopher Henry David Thoreau and author Ralph Waldo Emerson; poets Wallace Stevens, T. S. Eliot and E. E. Cummings; composer Leonard Bernstein; actor Jack Lemmon; architect Philip Johnson, and civil rights leader W. E. B. Du Bois. Among its most famous faculty members are biologists James D. Watson and E. O. Wilson.

Harvard affiliates' politics are generally liberal (center-left): Richard Nixon famously attacked it as the "Kremlin on the Charles". In 2004, the Harvard Crimson found that Harvard undergraduates favored Kerry over Bush by 73% to 19%, consistent with Kerry's margin in major eastern cities such as Boston and New York City.[2] At the same time, Harvard has been criticized as elitist and "hostile to progressive intellectuals". (Trumpbour) President George W. Bush, in fact, graduated from the Harvard Business School. Indeed, there are both prominent conservative and prominent liberal voices among the faculty of the various schools, such as Greg Mankiw and Alan Dershowitz.

Admissions

S. GOT INTO HARVARD WHO WOULD HAVE THOUGHT? I MEAN REALLY. TAKE THAT R.. Harvard's overall undergraduate acceptance rate for 2006 was 9.3%.[3], making it one of the most selective universities in the country. The 2006 figures from US News and World Report indicated that the business school admitted 14.3% of its applicants, the engineering division admitted 12.5%, the law school admitted 11.3%, the education school admitted 11.2%, and the medical school admitted 4.9%.[4]

Organization

Harvard is governed by two boards, the President and Fellows of Harvard College, also known as the Harvard Corporation and founded in 1650, and the Harvard Board of Overseers. The President of Harvard University is the day-to-day administrator of Harvard and is appointed by and responsible to the Harvard Corporation.

Harvard today has nine faculties, listed below in order of foundation:

- The Faculty of Arts and Sciences and its sub-faculty, the Division of Engineering and Applied Sciences, which together serve:

- Harvard College, the University's undergraduate portion (1636)

- The Graduate School of Arts and Sciences (organized 1872)

- The Harvard Division of Continuing Education, including Harvard Extension School and Harvard Summer School

- The Faculty of Medicine, including the Medical School (1782) and the Harvard School of Dental Medicine (1867).

- Harvard Divinity School (1816)

- Harvard Law School (1817)

- Harvard Business School (1908)

- The Graduate School of Design (1914)

- The Graduate School of Education (1920)

- The School of Public Health (1922)

- The John F. Kennedy School of Government (1936)

In 1999, the former Radcliffe College was reorganized as the Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study.

Sports and athletic facilities

Harvard's athletic rivalry with Yale is intense in every sport in which they meet, coming to a climax in their annual football meeting, which dates to 1875 and is usually called simply The Game. Harvard has won The Game for the past five years running. While Harvard's football team is no longer one of the country's best (it won the Rose Bowl in 1920) as it often was a century ago during football's early days, it, along with Yale, has influenced the way the game is played. In 1903, Harvard Stadium introduced a new era into football with the first-ever permanent reinforced concrete stadium of its kind in the country. The sport eventually adopted the forward pass (invented by Yale coach Walter Camp) because of the stadium's structure.

Today Harvard does field top teams in several other sports, such as ice hockey (with a strong rivalry against Cornell), rowing, and squash, even recently winning the NCAA title in Men's and Women's Fencing. But like other Ivy League universities, Harvard does not offer athletic scholarships. As of 2006, there were 41 Division I intercollegiate varsity sports teams for women and men at Harvard, more than at any other NCAA Division I college in the country.

Harvard has several fight songs, the most played of which, especially at football games, are "Ten Thousand Men of Harvard" and "Harvardiana" ("Fair Harvard", while musically better known outside the university, is chiefly a commencement song).

Harvard has several athletic facilities, such as the Lavietes Pavilion, a multi-purpose arena and home to the Harvard basketball teams. The Malkin Athletic Center, known as the "MAC," serves both as the University's primary recreation facility and as a satellite location for several varsity sports. The five story building includes two cardio rooms, an Olympic-size swimming pool, a smaller pool for aquaerobics and other activities, a mezzanine, where all types of classes are held at all hours of the day, and an indoor cycling studio, three weight rooms, and a three-court gym floor to play basketball. The MAC also offers personal trainers and specialty classes. The MAC is also home to Harvard volleyball, fencing, and wrestling. The offices of women's field hockey, lacrosse, soccer, softball, and men's soccer are also in the MAC.

Weld Boathouse and Newell Boathouse house the women's and men's rowing teams, respectively. The Bright Hockey Center hosts the Harvard hockey teams, and the Murr Center serves both as a home for Harvard's squash and tennis teams as well as a strength and conditioning center for all athletic sports. For more information on Harvard's sports facitilies, go to Harvard's official athletics site.

Library system and museums

The Harvard University Library System, centered in Widener Library in Harvard Yard and comprising over 90 individual libraries and over 15.3 million volumes, is the largest university library system in the world and, after the Library of Congress, the second-largest library system in the United States. Cabot Library in the Science Center, Lamont Library in Harvard Yard, and Widener Library are three of the most popular libraries for undergraduates to use, with easy access and central locations. Houghton Library is the primary repository for Harvard's rare books and manuscripts. America's oldest collection of maps, gazetteers, and atlases both old and new are stored in Pusey Library and is open to the public.

Harvard operates several art museums, including the Fogg Museum of Art (with galleries featuring history of Western art from the Middle Ages to the present, with particular strengths in Italian early Renaissance, British pre-Raphaelite, and 19th-century French art); the Adolph Busch Museum (formerly Busch-Reisinger Museum, formerly Germanic Museum) (central and northern European art; and a Flentrop pipe organ, familiar from recordings by E. Power Biggs); the Sackler Museum (ancient, Asian, Islamic and later Indian art); the Museum of Natural History, which contains the famous Blaschka Glass Flowers exhibit; the Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology, specializing in the cultural history and civilizations of the Western Hemisphere; and the Semitic Museum.

Harvard in fiction and popular culture

Love Story, by Harvard alumnus (and Yale professor) Erich Segal, the much-beloved and also much-ridiculed tearjerker of the 1970s, concerns a romance between a Harvard student and a Radcliffe student. The novel is deeply imbued with local color.[5]. A current Harvard tradition is the annual showing of the film Love Story to incoming freshman, during which the film is openly mocked by the Crimson Key Society, a tour-giving organization on campus.

Though Harvard has been featured in many US films, including Legally Blonde, The Firm, The Paper Chase, Good Will Hunting, With Honors, How High, and Harvard Man, the University has not allowed any movies to be filmed on its campus since Love Story in the 1960s; most films are shot in look-alike cities, such as Toronto, and colleges such as Wheaton and Bridgewater State [6]. Also set in Harvard is Korean hit TV series Love Story in Harvard[7], filmed at University of Southern California. Many movies have characters identified as Harvard graduates, including A Few Good Men, American Psycho, and Two Weeks Notice.

The novel, The Da Vinci Code, has its main character, Robert Langdon, as a Harvard "professor of symbology," although no such field exists at Harvard.[8])

Matthew Pearl's 2004 mystery novel, The Dante Club, is set in Cambridge, 1865 and Harvard professors Oliver Wendell Holmes, James Russell Lowell, and Henry Wadsworth Longfellow and a shadowy anti-Dante plot involving the Harvard Corporation (which prefers Latin to Italian, and fears contamination by Dante's Papist theology).

Overview of the campus

The main campus is centered around Harvard Yard in central Cambridge, and extends into the surrounding Harvard Square neighborhood. The Harvard Business School and many of the university's athletics facilities, including Harvard Stadium, are located in Allston, on the other side of the Charles River from Harvard Square. Harvard Medical School and the Harvard School of Public Health are located in the Longwood district of Boston.

Harvard Yard itself contains the central administrative offices and main libraries of the University, several academic buildings, Memorial Church, and the majority of the freshman dormitories. Sophomores, Juniors, and Seniors live in twelve residential Houses, 9 of which are south of Harvard Yard along or near the Charles River and 3 of which are located in a residential neigborhood half a mile northwest of the Yard called the Quadrangle.

Residential Houses

Nearly all students at Harvard College live on campus. First-year students live in the freshman dormitories in or near Harvard Yard. Upperclass students live mainly in a system of twelve residential "Houses", which serve as administrative units of the College as well as dormitories. Each House is presided over by a "Master"—a senior faculty member who is responsible for guiding the social life and community of the House—and a "Senior Tutor", who acts as dean of the students in the House in its administrative role.

The House system was instituted by Harvard president Abbott Lawrence Lowell in the 1930s, although the number of Houses, their demographics, and the methods by which students are assigned to particular Houses have all changed drastically since the founding of the system. Funds for the Houses were donated by Edward Harkness, a Yale graduate, who had previously failed to persuade Yale of its merits (but which later adopted a very similar "college" system). Lowell modeled it on the system of constituent colleges of Oxford and Cambridge, and the Houses borrow terminology from Oxford and Cambridge such as Junior Common Room (the set of undergraduates affiliated with a House) and Senior Common Room (the Master, Senior Tutor, and other faculty members, advisors, and graduate students associated with the House). Non-faculty members of the Senior Common Room of a House are given the title "Tutor".

Nine of the Houses are situated south of Harvard Yard, near the busy commercial district of Harvard Square, along or close to the northern banks of the Charles River, and so are known colloquially as the River Houses. These are:

- Adams House, named for several alumni of that name, including U. S. President John Adams;

- Dunster House, named for Harvard's first President, Henry Dunster;

- Eliot House, named for Harvard President Charles William Eliot;

- Kirkland House, named for Harvard President John Thornton Kirkland;

- Leverett House, named for Harvard President John Leverett;

- Lowell House, said to be named for the Harvard-affiliated Lowell family in general (but the most obvious reference is to Abbott Lawrence Lowell);

- Mather House, named for Harvard President Increase Mather;

- Quincy House, named for Harvard President (and sometime mayor of Boston) Josiah Quincy III;

- Winthrop House, more officially called John Winthrop House, named for two famous men of that name: Massachusetts Bay Colony founder John Winthrop and his great-great-great-grandson John Winthrop, 2nd Hollis Professor of Mathematics and Natural Philosophy

The remainder of the residential Houses are located around Harvard's Quadrangle (or "the Quad", formerly the "Radcliffe Quadrangle"), in a more suburban residential neighborhood half a mile (800 m) northwest of Harvard Yard. These housed Radcliffe College students until Radcliffe merged its residential system with Harvard. They are:

- Cabot House, previously called South House, renamed in 1983 for Harvard donors Thomas Dudley Cabot and Virginia Cabot;

- Currier House, named for Radcliffe alumna Audrey Bruce Currier;

- Pforzheimer House, often called PfoHo for short, previously called North House, renamed in 1995 for Harvard donors Carl and Carol Pforzheimer

There is a thirteenth House, Dudley House [9], which is nonresidential but still fulfills, for some graduate students and off-campus undergraduates (including members of the Dudley Co-op) the same administrative and social functions as the residential Houses do for undergraduates who live on campus. It is named after Thomas Dudley, who signed the charter of Harvard College when he was Governor of the Massachusetts Bay Colony.

Radcliffe Yard, the center of the campus of the former Radcliffe College (and now Radcliffe Institute), is west of Harvard Yard, adjacent to the Graduate School of Education.

Major campus expansion

Throughout the past several years, Harvard has purchased large tracts of land in Allston, a short walk across the Charles River from Cambridge, with the intent of major expansion southward. The university now owns approximately fifty percent more land in Allston than in Cambridge. Various proposals to connect the traditional Cambridge campus with the new Allston campus include new and enlarged bridges, a shuttle service and/or a tram.

One of the foremost driving forces for Harvard's pending expansion is its goal of substantially increasing the scope and strength of its science and technology programs. The university plans to construct two 500,000 square foot (50,000 m²) research complexes in Allston, which would be home to several interdisciplinary programs, including the Harvard Stem Cell Institute and an enlarged Engineering department.

In addition, Harvard intends to relocate the Harvard Graduate School of Education and the Harvard School of Public Health to Allston. The university also plans to construct several new undergraduate and graduate student housing centers in Allston, and it is considering large-scale museums and performing arts complexes as well.

History

Harvard's foundation in 1636 came in the form of an act of the colony's Great and General Court. By all accounts the chief impetus was to allow the training of home-grown clergy so the Puritan colony would not need to rely on immigrating graduates of England's Oxford and Cambridge universities for well-educated pastors, "dreading," as a 1643 brochure put it, "to leave an illiterate Ministry to the Churches." In its first year, seven of the original nine students left to fight in the English Civil War.

Harvard was also founded as a school to educate American Indians in order to train them as ministers among their tribes. Harvard's Charter of 1650 calls for "the education of the English and Indian youth of this Country in knowledge and godliness". Indeed, Harvard and missionaries to the local tribes were intricately connected. The first Bible to be printed in the entire North American continent was printed at Harvard in an Indian language, Massachusett. Termed the Eliot Bible since it was translated by John Eliot, this book was used to facilitate conversion of Indians, ideally by Harvard-educated Indians themselves. Harvard's first American Indian graduate, Caleb Cheeshahteaumuck from the Wampanoag tribe, was a member of the class of 1665. Caleb and other students-- English and American Indian alike-- lived and studied in a dormitory known as the Indian College, which was founded in 1655 under then-President Charles Chauncy. In 1698 it was torn down owing to neglect. The bricks of the former Indian College were later used to build the first Stoughton Hall. Today a plaque on the SE side of Matthews Hall in Harvard Yard, the approximate site of the Indian College, commemorates the first American Indian students who lived and studied at Harvard University.

The connection to the Puritans can be seen in the fact that, for its first few centuries of existence, the Harvard Board of Overseers included, along with certain commonwealth officials, the ministers of six local congregations (Boston, Cambridge, Charlestown, Dorchester, Roxbury and Watertown), who today, although no longer so empowered, are still by custom allowed seats on the dais at commencement exercises.

Despite the Puritan atmosphere, from the beginning the intent was to provide a full liberal education such as that offered at European universities, including the rudiments of mathematics and science ('natural philosophy') as well as classical literature and philosophy.

During the Revolutionary War, General Washington and the Continental Army quartered in Harvard buildings and organized military exercises in Cambridge Common.

Between 1800 and 1870 a transformation of Harvard occurred which E. Digby Baltzell[10] calls "privatization." Harvard had prosperred while Federalists controlled state government, but "in 1824 the federalist party was finally defeated forever in Massachusetts; the triumphant Jeffersonian-Republicans cut off all state funds." By 1870, the "magistrates and ministers" on the Board of Overseers had been completely "replaced by Harvard alumni drawn primarily from the ranks of Boston's upper-class business and professional community" and funded by private endowment.

During this period, Harvard experienced unparalleled growth that put it into a different category from other colleges. Ronald Story[11] notes in 1850, Harvard's total assets were "five times that of Amherst and Williams combined, and three times that of Yale.... By 1850, it was a genuine university, 'unequalled in facilities,' as a budding scholar put it by any other institution in America—the 'greatest University,' said another, 'in all creation.'"

Story[12] also notes that "all the evidence... points to the four decades from 1815 to 1855 as the era when parents, in Henry Adams's words, began 'sending their children to Harvard College for the sake of its social advantages.'"

Steinberg[13] notes that "a climate of intolerance prevailed in many eastern colleges long before discriminatory quotas were contemplated" and noted that "Jews tended to avoid such campuses as Yale and Princeton, which had reputations for bigotry.... Under President Eliot's administration, Harvard earned a reputation as the most liberal and democratic of the Big Three, and therefore Jews did not feel that the avenue to a prestigious college was altogether closed." This was to change sharply under Eliot's successor, A. Lawrence Lowell.

Harvard became the bastion of a distinctly Protestant elite--the so-called Boston Brahmin class--well into the 20th century. Its discriminatory policies against immigrants, Catholics and Jews were partly responsible for the founding of Boston College in 1863 and Brandeis University in 1948. The social milieu at Harvard is depicted in Owen Wister's Philosophy 4, set in the 1870s, which contrasts the character and demeanor of two undergraduates who "had colonial names (Rogers, I think, and Schuyler)" with that of their tutor, one Oscar Maironi, whose "parents had come over in the steerage." Myron Kaufman's 1957 novel Remember Me to God follows the life of a Jewish undergraduate in 1940s Harvard, navigating the shoals of casual antisemitism as he desperately seeks to become a gentleman, be accepted into The Pudding, and marry the Yankee protestant Wimsy Talbot.

In 2002, it was revealed by The Crimson that in 1920 "Harvard University maliciously persecuted and harassed" those it believed to be gay via a "Secret Court" led by Harvard President A. Lawrence Lowell. The inquistions and expulsions carried out by this tribunal, in conjunction with the "vindictive tenacity of the university in ensuring that the stigmatization of the expelled students would persist throughout their productive lives" led to several suicides. Wright placed the origins of the purge in an astounding ignorance of the day's most advanced thinking about sexual inversion, an excessive idealization of the idea of the "Harvard man", and an anxiety to dissociate the university from a reputation as a haven for homosexuals. Current President Lawrence Summers characterized the episode as "Part of a past that we have rightly left behind", and "abhorrent and an affront to the values of our university".[14]

Firsts

Harvard "firsts" include: the appointment in 1901 of Sir William Ashley, making him the first lecturer in economic history in the English-speaking world.

Recent developments

On February 21, 2006, president Lawrence Summers announced his intention to resign the presidency, effective June 30, 2006. His resignation came just one week before a second planned vote of no confidence by the Harvard Faculty of Arts and Sciences. Former president Derek Bok will serve as interim president starting July 1. Members of Harvard's Faculty of Arts and Sciences, which instructs graduate students in GSAS and undergraduates in Harvard College, had passed an earlier motion of "lack of confidence" in Summers' leadership on March 15, 2005 by a 218-185 vote, with 18 abstentions. The 2005 motion was precipitated by comments about the causes of gender demographics in academia made at a closed academic conference and leaked to the press. In response, Summers convened two committees to study this issue: the Task Force on Women Faculty and the Task Force on Women in Science and Engineering. Summers had also pledged $50 million to support their recommendations and other proposed reforms.

In the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina, Harvard, along with numerous other institutions of higher education across the United States and Canada, offered to take in students who were unable to attend universities and colleges that were closed for the fall semester. Twenty-five students were admitted to the College, and the Law School made similar arrangements. Tuition was not charged and housing was provided.

Controversy ensued, however, when the Administrative Board ruled that those students visiting from Tulane University would have to return to their home college for spring semester, and would not be able to apply for inter-year transfer, a policy consistent with other comparable universities like Yale's. The Undergraduate Council advocated for the students to stay or be allowed inter-year transfer rights, whereas the Crimson posted occasional op-ed pieces about the necessity of the students leaving to maintain integrity of contracts.

Notable student organizations

- The Harvard Crimson is the nation's oldest continuously published daily college newspaper and is doordropped to student rooms.

- The Harvard Advocate is the oldest college literary publication in the country. Past members include T.S. Eliot and Theodore Roosevelt.

- The Harvard Lampoon, an undergraduate humor organization and publication founded in 1876 and rival to the Harvard Crimson. The erratically produced magazine was originally modelled on the former British satirical periodical Punch, and has outlived it to become the world's second-oldest humor magazine (after the Yale Record). Conan O'Brien was president of the Lampoon. The National Lampoon was founded as an offshoot in 1970 from the Harvard Lampoon.

- Radio station WHRB (95.3FM Cambridge), is run exclusively by Harvard students, and is given space on the Harvard campus in the basement of Pennypacker Hall, a freshman dorm. Known throughout the Boston metropolitan area for its classical, jazz, underground rock and blues programming, WHRB uses the radio "Orgy" format, where the entire catalog of a certain band, record, or artist is played in sequence.

- The Institute of Politics, housed in Harvard's Kennedy School of Government and features keynotes daily, student study groups with political activists and leaders, and a center of nonpartisan political community at Harvard.

- Harvard University Choir, the oldest university choir in the nation, formally established in 1834 but in existence since the eighteenth century, performs the oldest Christmas Carol Services in continuous existence in North America.

- Harvard Glee Club, the oldest college chorus in America, founded in 1858.

- Harvard Radcliffe Orchestra, founded in 1808.

- Harvard Model Congress, the nation's oldest and largest congressional simulation conference, provides thousands of high school students from across the U.S. and abroad with the opportunity to experience American government first-hand.

- The Harvard Project for Asian and International Relations is Harvard's oldest student group dedicated to Asian International Relations. It organizes Harvard's largest annual event in Asia.

People associated with Harvard University

Seventy-five Nobel Prize winners are affiliated with the university, and since 1974, nineteen Nobel Prize winners and fifteen Pulitzer Prize winners have served on the Harvard faculty. For details, see Nobel Prize laureates by university affiliation.

- People associated with Harvard University

- Presidents of Harvard

- Notable non-graduate alumni of Harvard

Views of Harvard

In 1893, Baedeker's guidebook called Harvard "the oldest, richest, and most famous of American seats of learning." The first two facts remain true today; the third is also arguably true. As of 2005, Harvard was ranked first among world universities by Times Higher Education Supplement and the Academic Ranking of World Universities[15] and shared the first spot with Princeton in US News and World Report rankings.

Perhaps because of this prominence, Harvard is the target of a number of criticisms, some of them leveled at other research-based American universities. It has been accused of grade inflation, as have other Ivy League institutions and Stanford University.[16]. The Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching, The New York Times, and some students have criticized Harvard for its reliance on teaching fellows in undergraduate education, as many in the faculty are engaged in research (assistant teaching is not taken into account by the major college and university rankings); they consider this to be detrimental to the quality of education.[17][18] The New York Times article also detailed that the problem was prevalent in other Ivy League schools.

In 2005, The Boston Globe reported obtaining a 21-page Harvard internal memorandum that expressed concern about undergraduate student satisfaction based on a 2002 Consortium on Financing Higher Education (COFHE) survey of 31 top universities. [19] The Harvard internal memorandum noted that: "Harvard students are less satisfied with their undergraduate educations than the students at almost all of the other COFHE schools. Harvard student satisfaction compares even less favorably to satisfaction at our closest peer institutions." While the actual survey results as reported by the Globe are open to interpretation, the Harvard Crimson editorial board opined that "we believe the implications of this survey are significant, and the administration ought to make satisfying undergraduates a top priority for the near future." [20] The Globe quoted Lawrence Buell, former Harvard Dean of Undergraduate Education, as saying "I think we have to concede that we are letting our students down."

The Globe presented COFHE survey results and quotes from Harvard students that suggest problems with faculty availability, quality of instruction, quality of advising, social life on campus, and sense of community dating back to at least 1994. The magazine section of the Harvard Crimson echoed similar academic and social criticisms. [21] [22] The Harvard Crimson quoted Harvard College Dean Benedict Gross as being aware of and committed to improving the issues raised by the COFHE survey. [23] However, in the same article, Harvard Professor Harvey C. Mansfield expressed skepticism at the willingness of faculty to improve the undergraduate experience: "I think the administration has a commitment to improving Harvard, but I don't think the majority of the faculty does. They are the ones who are complacent and deserve most of the criticism."

The undergraduate admissions office's preference for children of alumni[24] has been the subject of much scrutiny and debate. Under new financial aid guidelines, parents in families with incomes of less than $60,000 will no longer be expected to contribute any money at all to the cost of attending Harvard for their children, including room and board. Families in the $60,000 to $80,000 contribute an amount of only a few thousand dollars a year.

Harvard and its students have also frequently been criticized for self-promotion in various forms, although it is somewhat unclear how this differentiates Harvard from the school pride of any other university. In "A Flood of Crimson Ink" (Wall Street Journal, April, 2005) [25], the author asserts that one reason Harvard receives much attention from the press is because "Harvard graduates are disproportionately represented in the upper echelons of American journalism." Critics of Harvard self-marketing charge that the school is filled with students "specifically selected for their skills at self-promotion" [26]. This undoubtedly applies to other top schools in view of what is necessary to gain acceptance to highly competitve universities in the U.S. today.

Further reading

- John T. Bethell, Harvard Observed: An Illustrated History of the University in the Twentieth Century, Harvard University Press, 1998, ISBN 0674377338

- John Trumpbour, ed., How Harvard Rules, Boston: South End Press, 1989, ISBN 0896082830

- Hoerr, John, We Can't Eat Prestige: The Women Who Organized Harvard; Temple University Press, 1997, ISBN 1566395356

External links

Template:Mapit-US-buildingscale

References

- ^ Zachary M. Seward. "Endowment Up 21 Percent". The Harvard Crimson. September 15, 2004. http://www.thecrimson.com/article.aspx?ref=503347

- ^ "World University Rankings". The Times Educational Supplement. http://www.thes.co.uk/worldrankings/

- ^ "The Class of 2010 is the most diverse in Harvard history" March 30, 2006. http://www.news.harvard.edu/gazette/daily/2006/03/30-admissions.html

- ^ Don Peck. "The Selectivity Illusion". The Atlantic Monthly. November 2003. http://www.theatlantic.com/doc/prem/200311/peck

- ^ Rogers, Mary F. (1991) Novels, Novelists, and Readers: Toward a Phenomenological Sociology of Literature. SUNY Press, ISBN SUNY Press p. 102 (List of Harvard-atmosphere items mentioned in first two chapters)

- ^ Ruffling Religious Feathers, Harvard Crimson article, February 12, 2004: "symbology" doesn't exist, and semiology isn't represented at Harvard.

- ^ "The Best Graduate Schools 2006". U.S. News & World Report. http://www.usnews.com/usnews/edu/grad/rankings/rankindex_brief.php

- ^ Kaplan (2004), Unofficial, Unbiased Guide to the 331 Most Interesting Colleges 2005, p. 174; Simon and Schuster, ISBN 0743251997 ("Duke: the Harvard of the North")

- ^ Steinberg, Stephen (2001), The Ethnic Myth. Beacon Press, ISBN 080704153X. (Harvard most democratic of the Big Three under Eliot, p. 234)

- ^ (1994) Baltzell, Digby E. and Howard G. Schneiderman, Judgment and Sensibility: Religion and Stratification." Transaction Publishers, ISBN 0819550442 1560000481. The material cited is a review of a book by Ronald Story (1980), The Forging of an Aristocracy: Harvard and the Boston Upper Class, 1800-1870, Wesleyan University Press, ISBN 0819550442.

- ^ Story, Ronald (1980), The Forging of an Aristocracy: Harvard and the Boston Upper Class, 1800-1870, Wesleyan University Press, ISBN 0819550442 (p. 50: Harvard's explosive growth from 1800 to 1850 separate it from other colleges)

- ^ Story (1980) op. cit. p. 97, (1815-1855 as the era when Harvard began to be perceived as socially advantageous)

- ^ Rebecca D. O'Brien. "Kerry Tops Crimson Poll". The Harvard Crimson. October 29, 2004. http://www.thecrimson.com/article.aspx?ref=504151

- ^ Ty Burr. "Reel Boston". The Boston Globe. February 27, 2005. http://www.boston.com/news/globe/magazine/articles/2005/02/27/reel_boston/

- ^ Nina M. Catalano. "Harvard TV Show Popular in Korea". The Harvard Crinsom. December 13, 2004. http://www.thecrimson.com/printerfriendly.aspx?ref=505050

- ^ Linda Wertheimer. "Harvard Grade Inflation". All Things Considered. National Public Radio. November 21, 2001. http://www.npr.org/templates/story/story.php?storyId=1133702

- ^ Rebecca M. Milzoff, Amit R. Paley, and Brendan J. Reed. "Grade Inflation is Real". Fifteen Minutes. March 1, 2001. http://www.thecrimson.com/fmarchives/fm_03_01_2001/article4A.html

- ^ "Princeton becomes first to formally combat grade inflation". Associated Press. April 26, 2004. http://www.usatoday.com/news/education/2004-04-26-princeton-grades_x.htm

- ^ David L. Hicks. "Should Our Colleges Be Ranked?" Letter to The New York Times. September 20, 2002. http://query.nytimes.com/gst/fullpage.html?res=9803E5D71130F933A1575AC0A9649C8B63

- ^ John Merrow. "Grade Inflation: It's Not Just an Issue for the Ivy League". Carnegie Perspectives. The Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching. June 2004. http://www.carnegiefoundation.org/perspectives/perspectives2004.June.htm

- ^ Mark Alden Branch. "Who's Teaching Whom?" Yale Alumni Magazine. Summer 1999 http://www.yalealumnimagazine.com/issues/99_07/GESO.html

- ^ http://www.dartreview.com/archives/1998/04/29/harvard_research_and_destroy.php

- ^ Bok, in Derek Bok, Universities in the Marketplace, Princeton (2003)

- ^ Rosovsky, in Henry Rosovsky, The University: An Owner's Manual, Norton (1990)

- ^ John Trumpbour, ed., How Harvard Rules, South End (1989)

- ^ http://www.digitas.harvard.edu/~perspy/old/issues/1997/nov/second.html

- ^ http://www.nytimes.com/2005/03/01/education/01college.html

- ^ http://www.cfoeurope.com/displayStory.cfm/1777470

- ^ http://www.thecrimson.com/article.aspx?ref=503493

- ^ Wright, William, Harvard's Secret Court: The Savage 1920 Purge of Campus Homosexuals, St. Martin's Press, New York, 2005. ISBN 0312322712.