Auriga

| Constellation | |

| |

| Abbreviation | Aur[1] |

|---|---|

| Genitive | Aurigae |

| Pronunciation |

|

| Symbolism | the Charioteer |

| Right ascension | 6 |

| Declination | +40 |

| Quadrant | NQ1 |

| Area | 657[3] sq. deg. (21st) |

| Main stars | 5, 8 |

| Bayer/Flamsteed stars | 65 |

| Stars with planets | 6 |

| Stars brighter than 3.00m | 4 |

| Stars within 10.00 pc (32.62 ly) | 1 |

| Brightest star | Capella (α Aur) (0.08m) |

| Messier objects | 3[4] |

| Meteor showers | |

| Bordering constellations | |

| Visible at latitudes between +90° and −40°. Best visible at 21:00 (9 p.m.) during the month of Late February to early March. | |

Auriga is one of the 48 constellations listed by the 2nd-century astronomer Ptolemy, and remains one of the 88 modern constellations. Located north of the celestial equator, its name is the Latin word for "charioteer", associating it with many mythological charioteers. Auriga is most prominent during winter evenings in the Northern Hemisphere, along with the five other constellations that have stars in the Winter Hexagon asterism. Because of its northern declination, Auriga is only visible as far as 34° south; for observers further south it lies partially or fully below the horizon. A large constellation with an area of 657 square degrees, it is more than 1200 times the size of the full moon, 50% of the size of the largest constellation, Hydra, and over 9 times the area of the smallest constellation, Crux.

Its brightest star, Capella, is an unusual multiple star system, as well as one of the brightest stars in the night sky. Beta Aurigae is one of many interesting variable stars in the constellation; nearby Epsilon Aurigae is an eclipsing binary with an unusually long period and has been studied intensively. Because of its position near the winter Milky Way, Auriga has many bright open clusters in its borders, including M36, M37, and M38, popular targets for amateur astronomers. It also has one prominent nebula, the Flaming Star Nebula, associated with the variable star AE Aurigae.

Auriga's stars were incorporated into several constellations in Chinese mythology, including the celestial emperors' chariots, made up of the modern constellation's brightest stars. It also contains the radiant for the Aurigids, Zeta Aurigids, Delta Aurigids, and the hypothesized Iota Aurigids.

History and mythology

The first record of Auriga's stars was in Mesopotamia as a constellation called GAM, representing a scimitar or crook. However, this may have represented just Capella (alpha Aurigae) or the modern constellation as a whole. It was also called Gamlum or MUL.GAM in the MUL.APIN. The crook of Auriga stood for a goat-herd or shepherd. It was formed from most of the stars of the modern constellation; all of the bright stars were included except for Elnath, traditionally assigned to both Taurus and Auriga. Later, Bedouin astronomers created constellations that were groups of animals, where each star represented one animal. The stars of Auriga comprised a herd of goats, an association also present in Greek mythology.[7] The association with goats carried into the Greek astronomical tradition, though it later became associated with a charioteer along with the shepherd.[8]

In Greek mythology, Auriga is often identified as the mythological Greek hero Erichthonius of Athens, the chthonic son of Hephaestus who was raised by the goddess Athena. Erichthonius was generally credited to be the inventor of the quadriga, the four-horse chariot, which he used in the battle against the usurper Amphictyon, the event that made Erichthonius the king of Athens.[9][10] His chariot was created in the image of the Sun's chariot, the reason Zeus placed him in the heavens.[11] Erichthonius has also been credited with inventing the chariot due to his lameness.[2] The Athenian hero then dedicated himself to Athena and soon after, Zeus raised him into the night sky in honor of his ingenuity and heroic deeds.[12] However, Auriga is also sometimes named as Myrtilus, who was Hermes's son and who was the charioteer of Oenomaus.[10] This association is supported by the fact that depictions of Auriga rarely show a chariot, because Myrtilus's chariot was destroyed in a race, designed for suitors to win the heart of Oenomaus's daughter, Hippodamia. Myrtilus earned his position in the sky when Hippodamia's successful suitor, Pelops, killed him, despite his complicity in helping Pelops win her hand. After his death, Myrtilus's father Hermes placed him in the sky. Yet another mythological association of Auriga is Theseus's son Hippolytus. He was ejected from Athens after he refused the romantic advances of his stepmother Phaedra, who committed suicide. He was killed when his chariot wrecked, but revived by Asclepius.[11][13] Regardless of Auriga's specific representation, it is likely that it was created by the ancient Greeks to commemorate the importance of the chariot in their society.[14]

An incidental appearance of Auriga in Greek mythology is as the limbs of Medea's brother. In the myth of Jason and the Argonauts, as they journeyed home, Medea killed her brother and dismembered him, flinging the parts of his body into the sea, represented by the Milky Way. Each individual star represents a different limb.[15]

Capella is associated with the mythological she-goat Amalthea, who breast-fed the infant Zeus. It forms an asterism with the stars Epsilon Aurigae, Zeta Aurigae, and Eta Aurigae, the latter two of which are known as the Haedi (the Kids).[16][9] Though most often associated with Amalthea, Capella has also been associated with Amalthea's owner, a nymph. The myth of the nymph says that the goat's hideous appearance, resembling a Gorgon, was partially responsible for the Titans' defeat, because Zeus skinned the goat and wore it as his aegis.[11] The asterism containing the three goats had been a separate constellation; however, Ptolemy merged the Charioteer and the Goats in the 2nd century Almagest.[14] Before Ptolemy's merge, Capella was sometimes also seen as its own constellation—by Pliny the Elder and Manilius—called Capra, Caper, or Hircus, all of which relate to its status as the "goat star".[17] Zeta Aurigae and Eta Aurigae were first called the "Kids" by Cleostratus, an ancient Greek astronomer.[11]

Traditionally, illustrations of Auriga represent it as a chariot and its driver. The charioteer holds a goat over his left shoulder and has two kids under his left arm; he holds the reins to the chariot in his right hand.[2] However, depictions of Auriga have been inconsistent over the years. The reins in his right hand have also been drawn as a whip, though Capella is almost always over his left shoulder and the Kids under his left arm. The 1488 atlas Hyginus deviated from this typical depiction by showing a four-wheeled cart driven by Auriga, who holds the reins of two oxen, a horse, and a zebra. Jacob Micyllus depicted Auriga in his Hyginus of 1535 as a charioteer with a two-wheeled cart, powered by two horses and two oxen. Arabic and Turkish depictions of Auriga varied wildly from those of the European Renaissance; one Turkish atlas depicted the stars of Auriga as a mule, called Mulus clitellatus by Johann Bayer.[17] One unusual representation of Auriga, from 17th century France, showed Auriga as Adam kneeling on the Milky Way, with a goat wrapped around his shoulders.[18]

Occasionally, Auriga is seen not as the Charioteer but as Bellerophon, the mortal rider of Pegasus who dared to approach Mount Olympus. In this version of the tale, Jupiter pitied Bellerophon for his foolishness and placed him in the stars.[19]

Some of the stars of Auriga were incorporated into a now-defunct constellation called Telescopium Herschelii. This constellation was introduced by Maximilian Hell to honor William Herschel's discovery of Uranus. Originally, it included two constellations, Tubus Hershelii Major [sic], in Gemini, Lynx, and Auriga, and Tubus Hershelii Minor [sic] in Orion and Taurus; both represented Herschel's telescopes. Johann Bode combined Hell's constellations into Telescopium Herschelii in 1801, located mostly in Auriga.[20]

Since the time of Ptolemy, Auriga has remained a constellation and is officially recognized by the International Astronomical Union, although like all modern constellations, it is now defined as a specific region of the sky that includes both the ancient pattern and the surrounding stars.[21][22] In 1922, the IAU defined its recommended three-letter abbreviation, "Aur".[23] The official boundaries of Auriga were defined in 1930 by Eugène Delporte as a polygon of 21 segments. Its right ascension is between 4h 37.5m and 7h 30.5m and its declination is between 27.9° and 56.2° in the equatorial coordinate system.[24]

In non-Western astronomy

The stars of Auriga were incorporated into several Chinese constellations. Wuche, the five chariots of the celestial emperors and the representation of the grain harvest, was a constellation formed by Alpha Aurigae, Beta Aurigae, Beta Tauri, Theta Aurigae, and Iota Aurigae. Sanzhu or Zhu was one of three constellations which represented poles for horses to be tethered. They were formed by the triplets of Epsilon, Zeta, and Eta Aurigae; Nu, Tau, and Upsilon Aurigae; and Chi and 26 Aurigae, with one other undetermined star. Xianchi, the pond where the sun set and Tianhuang, a pond, bridge, or pier, were also constellations in Auriga, though the stars that composed them are undetermined. Zuoqi, representing chairs for the emperor and other officials, was made up of nine stars in the east of the constellation. Bagu, a constellation mostly formed from stars in Camelopardalis representing different types of crops, included the northern stars of Delta and Xi Aurigae.[11]

In ancient Hindu astronomy, Capella represented the heart of Brahma and was important religiously. Ancient Peruvian peoples saw Capella, called Colca, as a star intimately connected to the affairs of shepherds.[18]

In Brazil, the Bororo people incorporate the stars of Auriga into a massive constellation representing a cayman; its southern stars represent the end of the animal's tail. The eastern portion of Taurus is the rest of the tail, while Orion is its body and Lepus is the head. This constellation arose because of the prominence of caymans in daily Amazonian life.[25]

The people of the Marshall Islands featured Auriga in the myth of Dümur, which tells the story of the creation of the sky. Antares in Scorpius represents Dümur, the oldest son of the stars' mother, and the Pleiades represent her youngest son. The mother of the stars, Ligedaner, is represented by Capella; she lived on the island of Alinablab. She told her sons that the first to reach an eastern island would become the King of the Stars, and asked Dümur to let her come in his canoe. He refused, as did each of her sons in turn, except for Pleiades. Pleiades won the race with the help of Ligedaner, and became the King of the Stars.[26]

Notable features

Stars

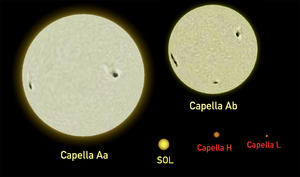

Alpha Aurigae (Capella), the brightest star in Auriga, is a G8 class star 43 light-years away[27] and the sixth brightest star in the night sky at magnitude 0.08.[9] Its traditional name is a reference to its mythological position as Amalthea; it is sometimes called the "Goat Star".[28][2][16] Capella's names all point to this mythology. In Arabic, Capella was called al-'Ayyuq, meaning "the goat", and in Sumerian, it was called mul.ÁŠ.KAR, "the goat star".[29] Capella is a spectroscopic binary with a period of 104 days; the components are both yellow giants,[16] more specifically, the primary is a G-type star and the secondary is between a G-type and F-type star in its evolution. The primary has a diameter of 18,000,000 kilometers and a mass of 3.09 M☉; the secondary has a diameter of 9,600,000 kilometers and a mass of 2.95 M☉. The two components are separated by 11300000 kilometers.[30] The star's status as a binary was discovered in 1899 at the Lick Observatory; its period was determined in 1919 by J.A. Anderson at the 100-inch Mt. Wilson Observatory telescope. It appears with a golden-yellow hue, though Ptolemy and Giovanni Battista Riccioli both described its color as red, a phenomenon attributed not to a change in Capella's color but to the idiosyncrasies of their color sensitivities.[28] Capella has an absolute magnitude of 0.3 and a luminosity of 160 L☉ (the primary is 90 L☉ and the secondary is 70 L☉).[30] It may be loosely associated with the Hyades, an open cluster in Taurus, because of their similar proper motion. Capella has another companion, Capella H, which is a pair of red dwarf stars located 11,000 astronomical units (0.17 light-years) from the main pair.[28]

Beta Aurigae (Menkalinan, Menkarlina)[16] is a bright A2 class star.[9] Its Arabic name comes from the phrase mankib dhu al-'inan, meaning "shoulder of the charioteer" and is a reference to Beta Aurigae's location in the constellation.[29] Menkalinan is 82 light-years away and has a magnitude of 1.90. Like Epsilon Aurigae, it is an eclipsing variable star that varies in magnitude by 0.1m. The two components are blue-white stars that have a period of 3.96 days.[16] Its double nature was discovered spectroscopically in 1890 by Antonia Maury,[28] making it the second spectroscopic binary ever discovered,[31] and its variable nature was discovered photometrically 20 years later by Joel Stebbins.[28] Menkalinan has an absolute magnitude of 0.6 and a luminosity of 50 L☉.[30] It is moving towards Earth at a speed of about 11 miles (18 km) per second. Beta Aurigae may be associated with a stream of approximately 70 stars including Delta Leonis and Alpha Ophiuchi; the proper motion of this group is comparable to that of the Ursa Major Moving Group, though the connection is only hypothesized. Besides its close eclipsing companion, Menkalinan has two other stars associated with it. One is an unrelated optical companion, discovered in 1783 by William Herschel; it has a magnitude of 10.5 and has a separation of 184 arcseconds. The other dim companion is likely associated gravitationally with the primary, as determined by their common proper motion. This 14th magnitude companion was discovered in 1901 by Edward Emerson Barnard. It has a separation of 12.6 arcseconds, and is approximately 350 astronomical units from the primary.[28]

Besides the particularly bright stars of Alpha and Beta Aurigae, the constellation also has many dimmer stars. Gamma Aurigae, now Beta Tauri (El Nath, Alnath) is an O-type star.[2] It was originally considered to be a part of both Auriga and Taurus, but is now classified only as Beta Tauri.[16][9] Iota Aurigae (Hasseleh, Kabdhilinan) is a K3 class star of magnitude 2.69;[9][30] it is 494 light-years away from Earth.[32] Iota Aurigae has an absolute magnitude of −2.3 and a luminosity of 700 L☉.[30] Though its proper motion is just 0.02 arcseconds per year, it has a radial velocity of 10.5 miles per second in recession.[28] Delta Aurigae is a K0-type star,[30] 126 light-years from Earth.[33] It has a magnitude of 3.72, an absolute magnitude of 0.2, and a luminosity of 60 L☉.[30] Lambda Aurigae (Al Hurr)[2] is a G0-type star of magnitude 4.71. It has an absolute magnitude of 4.4[30] and is located 41 light-years from Earth.[34] Nu Aurigae is a K0-type star of magnitude 3.97,[30] 230 light-years from Earth.[35] It has a luminosity of 60L☉ and an absolute magnitude of 0.2. Tau Aurigae is a G8-type star of magnitude 4.52. It has an absolute magnitude of 0.3[30] and is located 206 light-years from Earth.[36] Upsilon Aurigae is a GM1-type star of magnitude 4.74. It has an absolute magnitude of −0.5[30] and is located 526 light-years from Earth.[37] Pi Aurigae is an M3-type star of magnitude 4.26. It has an absolute magnitude of −2.4[30] and is 758 light-years from Earth.[38] Kappa Aurigae is a G8-type star of magnitude 4.25. It has an absolute magnitude of 0.3[30] and is 177 light-years from Earth.[39] Omega Aurigae is an A0-type star of magnitude 4.94. It has an absolute magnitude of 0.6[30] and is 171 light-years from Earth.[40] 2 Aurigae is a K3-type star of magnitude 4.78. It has an absolute magnitude of −0.2[30] and is 604 light-years from Earth.[41] 9 Aurigae is an F0-type star of magnitude 5.00. It has an absolute magnitude of 2.6[30] and is 86 light-years from Earth.[42] Mu Aurigae is an A3-type star of magnitude 4.86. It has an absolute magnitude of 1.8[30] and is 153 light-years from Earth.[43] Sigma Aurigae is a K4-type star of magnitude 4.89. It has an absolute magnitude of −0.3[30] and is 466 light-years from Earth.[44] Chi Aurigae is a B5-type star of magnitude 4.76. It has an absolute magnitude of −6.3 and is 3032 light-years from Earth. Xi Aurigae is an A2-type star of magnitude 4.99. It has an absolute magnitude of 0.8[30] and is 233 light-years from Earth.[45]

The most prominent variable star in Auriga is Epsilon Aurigae. Epsilon Aurigae (Al Maz, Almaaz)[9] is an F0 class eclipsing variable star[30] with an unusually long period of 27 years; its last minima occurred from 1982–1984 and 2009–2011.[10][2][16] The distance to the system is disputed, variously cited as 4600[30] and 2170 light-years.[46] The primary is a white supergiant, and the secondary may be itself a binary star within a large dusty disk. Its maximum magnitude is 3.0, but it stays at a minimum magnitude of 3.8 for approximately a year; its most recent eclipse began in 2009.[16] The primary has an absolute magnitude of −8.5 and an unusually high luminosity of 200,000 L☉, the reason it appears so bright at such a great distance.[30] Epsilon Aurigae is the longest-period eclipsing binary currently known.[9] The first observed eclipse of Epsilon Aurigae occurred in 1821, though its variable status was not confirmed until the eclipse of 1847–1848. From that time forward, many theories were put forth as to the nature of the eclipsing component. Epsilon Aurigae also has a noneclipsing component, which is visible as a 14th magnitude companion separated from the primary by 28.6 arcseconds. It was discovered by Sherburne Wesley Burnham in 1891 at the Dearborn Observatory, and is about 0.5 light-years from the primary.[28]

Another eclipsing binary in Auriga, part of the Haedi asterism with Epsilon Aurigae, is Zeta Aurigae (Sadatoni),[9] a K4-type[30] eclipsing variable star at a distance of 776[47] light-years with a period of 2 years and 8 months.[2][16] It has an absolute magnitude of −2.3.[30] The primary is an orange giant and the secondary is a smaller blue star similar to Regulus;[10] its period is 972 days. Zeta Aurigae's maximum magnitude is 3.7 and its minimum magnitude is 4.0.[16] The full eclipse of the small blue star by the orange giant lasts 38 days, with two partial phases of 32 days at the beginning and end.[28] The primary has a diameter of 150 D☉ and a luminosity of 700 L☉; the secondary has a diameter of 4 D☉ and a luminosity of 140 L☉.[10] Zeta Aurigae was spectroscopically determined to be a double star by Antonia Maury in 1897 and was confirmed as a binary star in 1908 by William Wallace Campbell. The two stars orbit each other about 500 million miles apart. Zeta Aurigae is moving away from Earth at a rate of 8 miles per second.[28] The last star in the asterism is Eta Aurigae, a B3 class star located 243 light-years from Earth[48] with a magnitude of 3.17.[9] It is a B3V class star, meaning that it is a blue-white hued main-sequence star.[28] Eta Aurigae is a part of the Haedi or "Kids" asterism, along with Zeta and Epsilon Aurigae. Eta Aurigae has an absolute magnitude of −1.7 and a luminosity of 450 L☉.[30] Eta Aurigae is moving away from Earth at a rate of 4.5 miles per second.[28]

T Aurigae (Nova Aurigae 1891) was a nova discovered at magnitude 5.0 on January 23, 1892, by Thomas David Anderson. It became visible to the naked eye by December 10, 1891, as shown on photographic plates examined after the nova's discovery. It then brightened by a factor of 2.5 in from December 11 to December 20, when it reached a maximum magnitude of 4.4. T Aurigae faded slowly in January and February 1892, then faded quickly during March and April, reaching a magnitude of 15 in late April. However, its brightness began to increase in August, reaching magnitude 9.5, where it stayed until 1895. Over the subsequent two years, its brightness decreased to 11.5, and by 1903, it was approximately 14th magnitude. By 1925, it had reached its current magnitude of 15.5. When the nova was discovered, its spectrum showed material moving at a high speed towards Earth. However, when the spectrum was examined again in August of 1892, it appeared to be a planetary nebula. Observations at the Lick Observatory by Edward Emerson Barnard showed it to be disc-shaped, with clear nebulosity in a diameter of 3 arcseconds. The shell had a diameter of 12 arcseconds in 1943. T Aurigae is classified as a slow nova, similar to DQ Herculis. Like DQ Herculis, WZ Sagittae, Nova Persei 1901 and Nova Aquilae 1918, it is a very close binary with a very short period. T Aurigae's period of 4.905 hours, comparable to DQ Herculis's period of 4.65 hours, and has a partial eclipse period of 40 minutes.[28]

There are many other variable stars of different types in Auriga. ψ1 Aurigae (Dolones)[30] is an orange supergiant, which ranges between magnitudes 4.8 and 5.7, though not with a regular period.[16] It has a spectral class of M0, an average magnitude of 4.91, and an absolute magnitude of −5.7.[30] Dolones is 3976 light-years from Earth.[49] RT Aurigae is a Cepheid variable which ranges between magnitudes 5.0 and 5.8 over a period of 3.7 days. A yellow-white supergiant, it lies at a distance of 1600 light-years.[16] It was discovered to be variable by English amateur T.H. Astbury in 1905.[28] Another Cepheid variable in Auriga is RX Aurigae, which varies in magnitude from a minimum of 8.0 to a maximum of 7.3; its spectral class ranges from type F to type G. It has a period of 11.62 days.[30] RW Aurigae is the prototype of its class of irregular variable stars. Its variability was discovered in 1906 by Lydia Ceraski at the Moscow Observatory. RW Aurigae's spectrum indicates a turbulent stellar atmosphere, and has prominent emission lines of calcium and hydrogen.[28] SS Aurigae is an SS Cygni-type variable star, classified as an explosive dwarf. Discovered by Emil Silbernagel in 1907, it is almost always at its minimum magnitude of 15, but brightens to a maximum up to 60 times brighter than the minimum an average of every 55 days, though the period can range from 50 days to more than 100 days. It takes about 24 hours for the star to go from its minimum to maximum magnitude. SS Aurigae is a very close binary star with a period of 4 hours and 20 minutes. Both components are small subdwarf stars; there has been dispute in the scientific community about which star originates the outbursts.[28] UU Aurigae is a variable red giant star at a distance of 2,000 light-years. It has a period of approximately 234 days and ranges between magnitudes 5.0 and 7.0.[16]

AE Aurigae is a blue-hued main-sequence variable star. Its normal magnitude is 6.0, but it varies irregularly. AE Aurigae is associated with the 9-light-year-wide Flaming Star Nebula (IC 405), which it illuminates. However, AE Aurigae likely entered the nebula only recently, as determined through the discrepancy between the radial velocities of the star and the nebula, 36 miles per second and 13 miles per second, respectively. It has also been hypothesized that AE Aurigae is a "runaway star" from the young cluster in the Orion Nebula, leaving the cluster approximately 2.7 million years ago. It is similar to 53 Arietis and Mu Columbae, other runaway stars from the Orion cluster.[28] The Flaming Star Nebula, is located near IC 410 in the celestial sphere. IC 410 obtained its name from its appearance in long exposure astrophotographs; it has extensive filaments that make AE Aurigae appear to be on fire.[50]

There are four Mira variable stars in Auriga: R Aurigae, UV Aurigae, U Aurigae, and X Aurigae, all of which are type M stars. R Aurigae, with a period of 457.5 days, ranges in magnitude from a minimum of 13.9 to a maximum of 6.7. UV Aurigae, with a period of 394.4 days, ranges in magnitude from a minimum of 10.6 to a maximum of 7.4. U Aurigae, with a period of 408.1 days, ranges in magnitude from a minimum of 13.5 to a maximum of 7.5. X Aurigae, with a particularly short period of 163.8 days, ranges in magnitude from a minimum of 13.6 to a maximum of 8.0.[30]

Auriga is also home to several less prominent binary and double stars. Theta Aurigae (Bogardus, Mahasim) is a blue-white A0p class binary star[9] of magnitude 2.62 with an luminosity of 75 L☉. It has an absolute magnitude of 0.1[30] and is 165 light-years from Earth.[51] The secondary is a yellow star of magnitude 7.1, which requires a telescope of 100 millimetres (3.9 in) in aperture to distinguish;[16] the two stars are separated by 3.6 arcseconds.[9] It is the eastern vertex of the constellation's pentagon.[52] Theta Aurigae is moving away from Earth at a rate of 17.5 miles per second. Theta Aurigae also has a second optical companion, discovered by Otto Wilhelm von Struve in 1852. The separation was at 52 arcseconds in 1978 and has been increasing since then because of the proper motion of Theta Aurigae, 0.1 arcseconds per year.[28] The separation of this magnitude 9.2 component was 2.2 arcminutes (130.7 arcseconds) in 2007 with an angle of 350°.[52] 4 Aurigae is a double star at a distance of 159 light-years. The primary is of magnitude 5.0 and the secondary is of magnitude 8.1.[16] 14 Aurigae is a white optical binary star. The primary is of magnitude 5.0 and is at a distance of 270 light-years; the secondary is of magnitude 7.9 and is at a distance of 82 light-years.[16] HD 30453 is spectroscopic binary of magnitude 5.9, with a spectral type assessed as either A8m or F0m, and a period of seven days.[53][54]

Deep-sky objects

The galactic anticenter is located about 3.5° to the east of Beta Aurigae. This marks the point on the celestial sphere opposite the location of the Galactic Center; hence, this region marks a less extensive and less luminous part of the dust band that forms the spiral arms of the Milky Way.[55][52] Auriga has many open clusters and other objects because the Milky Way runs through it. The three brightest open clusters are M36, M37 and M38, all of which are visible in binoculars or a small telescope in suburban skies.[2] A larger telescope resolves individual stars. Three other open clusters are NGC 2281, lying close to ψ7 Aurigae, NGC 1664, which is close to ε Aurigae, and IC 410 (surrounding NGC 1893), a cluster with nebulosity next to IC 405, the Flaming Star Nebula,[2] found about mid-way between M38 and ι Aurigae. AE Aurigae, a runaway star, is a bright variable star currently located within the Flaming Star Nebula.[28]

M36 (NGC 1960) is a young galactic open cluster with approximately 60 stars, most of which are relatively bright; however, only about 40 stars are visible in most amateur instruments.[52] It is at a distance of 3900 light-years and has an overall magnitude of 6.0; it is 14 light-years wide.[16][9][28] Its apparent diameter is 12.0 arcminutes.[52] Of the three open clusters in Auriga, M36 is both the smallest and the most concentrated, though its brightest stars are approximately 9th magnitude.[10] It was discovered in 1749 by Guillaume Le Gentil, the first of Auriga's major open clusters to be discovered. M36 features a 10-arcminute-wide knot of bright stars in its center, anchored by Struve 737, a double star with components separated by 10.7 arcseconds. Most of the stars in M36 are B type stars with rapid rates of rotation.[28] M36's Trumpler class is given as both I 3 r and II 3 m. Besides the central knot, most of the cluster's other stars appear in smaller knots and groups.[52]

M37 (NGC 2099) is another open cluster, larger than M36 and at a distance of 4200 light-years. It has 150 stars, one of which is a prominent orange star near the center, making it the richest cluster in Auriga.[16][10] M37 is approximately 25 light-years in diameter.[28] It is the brightest open cluster in Auriga with a magnitude of 5.6;[9] it has an apparent diameter of 23.0 arcminutes.[52] M37 was discovered in 1764 by Charles Messier, the first of many astronomers to laud its beauty. It was described as "a virtual cloud of glittering stars" by Robert Burnham, Jr. and Charles Piazzi Smyth commented that the star field was "strewed [sic]...with sparkling gold-dust".[28] The stars of M37 are older than those of M36; they are approximately 200 million years old. Most of the constituent stars are A type stars, though there are at least 12 red giants in the cluster as well.[28] M37's Trumpler class is given as both I 2 r and II 1 r. The stars visible in a telescope range in magnitude from 9.0 to 13.0; there are two 9th magnitude stars in the center of the cluster and an east to west chain of 10th and 11th magnitude stars.[52]

M38 is a diffuse open cluster at a distance of 3900 light-years, the least concentrated of the three main open clusters in Auriga;[28] it is classified as a Trumpler Class II 2 r or III 2 r cluster because of this.[52] It appears as a cross-shaped or pi-shaped object in a telescope and contains approximately 100 stars;[28] its overall magnitude is 6.4.[9][10] M38, like M36, was discovered by Guillaume Le Gentil in 1749. It has an apparent diameter of approximately 20 arcseconds and a true diameter of about 25 light-years. Unlike M36 or M37, M38 has a varied stellar population. The majority of the population consists of A and B type main sequence stars, the B type stars being the oldest members, and a number of G type giant stars. One yellow-hued G type star is the brightest star in M38 at a magnitude of 7.9.[28] The brightest stars in M38 are magnitude 9 and 10.[52] M38 is accompanied by NGC 1907, a smaller and dimmer cluster that lies half a degree south-southwest of M38; it is at a distance of 4200 light-years.[16] The smaller cluster has an overall magnitude of 8.2 and a diameter of 6.0 arcminutes, making it about a third the size of M38. However, NGC 1907 is a rich cluster, classified as a Trumpler Class I 1 m n cluster. It has approximately 12 stars of magnitude 9–10, and at least 25 stars of magnitude 9–12.[52]

IC 410, a faint nebula, is accompanied by the bright open cluster NGC 1893. The cluster is thin, with a diameter of 12 arcminutes and a population of approximately 20 stars. Its accompanying nebula has very low surface brightness, partially because of its diameter of 40 arcminutes. It appears in an amateur telescope with brighter areas in the north and south; the brighter southern patch shows a pattern of darker and lighter spots in a large instrument.[56] NGC 1893, of magnitude 7.5, is classified as a Trumpler Class II 3 r n or II 2 m n cluster, meaning that it is not very large and is somewhat bright. The cluster possesses approximately 30 stars of magnitude 9–12. In an amateur instrument, IC 410 is only visible with an Oxygen-III filter.[52] NGC 2281 is a small open cluster at a distance of 1500 light-years. It contains 30 stars in a crescent shape.[16] It has an overall magnitude of 5.4 and a fairly large diameter of 14.0 arcseconds, classified as a Trumpler Class I 3 m cluster. The brightest star in the cluster is magnitude 8; there are approximately 12 stars of magnitude 9–10 and 20 stars of magnitude 11–13.[52] NGC 1931 is a nebula in Auriga, slightly more than one degree to the west of M36. It is considered to be a difficult target for an amateur telescope. NGC 1931 has an approximate integrated magnitude of 10.1;[52] it is 3 by 3 arcminutes. However, it appears to be elongated in an amateur telescope.[56] Some observers may note a green hue in the nebula; a large telescope will easily show the nebula's "peanut" shape, as well as the quartet of stars that are engulfed by the nebula.[50] The open cluster portion of NGC 1931 is classed as a I 3 p n cluster; the nebula portion is classed as both an emission and reflection nebula.[52]

Another open cluster in Auriga is NGC 1664. It is fairly large, with a diameter of 18 arcminutes, and moderately bright, with a magnitude of 7.6, comparable to several other open clusters in Auriga. One open cluster with a similar magnitude is NGC 1778, with a magnitude of 7.7. This small cluster has a diameter of 7 arcminutes and contains 25 stars. NGC 1857, another small cluster, is slightly brighter at magnitude 7.0. It has a diameter of 6 arcminutes and contains 40 stars, making it far more concentrated than the similarly-sized NGC 1778. Far dimmer than the other open clusters is NGC 2126 at magnitude 10.2. Despite its dimness, NGC 2126 is as concentrated as NGC 1857, having 40 stars in a diameter of 6 arcminutes.[30]

Meteor showers

Auriga is home to two meteor showers. The Aurigids, named for the entire constellation and formerly called the "Alpha Aurigids", are renowned for their intermittent outbursts, such as those in 1935, 1986, 1994, and 2007.[57] They are associated with the comet Kiess (C/1911 N1), discovered in 1911 by Carl Clarence Kiess. The association was discovered after the outburst in 1935 by Cuno Hoffmeister and Arthur Teichgraeber.[58] The Aurigid outburst on September 1, 1935 prompted the investigation of a connection with Comet Kiess, though the 24-year delay between the comet's return caused doubt in the scientific community. However, the outburst in 1986 erased much of this doubt. Istvan Teplickzky, a Hungarian amateur meteor observer, observed many bright meteors radiating from Auriga in a fashion very similar to the confirmed 1935 outburst. Because the position of Teplickzky's observed radiant and the 1935 radiant were close to the position of Comet Kiess, the comet was confirmed as the source of the Aurigid meteor stream. The Aurigids had a spectacular outburst in 1994, when many grazing meteors—those that have a shallow angle of entry and seem to rise from the horizon— were observed in California. The meteors were tinted blue and green, moved slowly, and left trails at least 45° long. Because they had such a shallow angle of entry, some 1994 Aurigids lasted up to 2 seconds. Though there were only a few visual observers for part of the outburst, the 1994 Aurigids peak, which lasted less than two hours, was later confirmed by Finnish amateur radio astronomer Ilkka Yrjölä.[57] The connection with Comet Kiess was finally confirmed in 1994.[58] The 2007 outburst of the Aurigids was predicted by Peter Jenniskens and was observed by astronomers worldwide.[59] Despite some predictions that there would be no Alpha Aurigid outburst, many bright meteors were observed throughout the shower, which peaked on September 1 as predicted. Much like in the 1994 outburst, the 2007 Aurigids were very bright and often colored blue and green. The maximum zenithal hourly rate was 100 meteors per hour, observed at 4:15 AM, California time, by a team of astronomers flying on NASA planes.[60]

The Aurigids are normally a placid Class II meteor shower that peaks in the early morning hours of September 1, beginning on August 28 every year. Though the maximum zenithal hourly rate is 2–5 meteors per hour, the Aurigids are fast, with an entry velocity of 67 kilometres (42 mi)/sec. The annual Aurigids have a radiant located about two degrees north of Theta Aurigae, a third-magnitude star in the center of the constellation.[61] The Aurigids end on September 4.[62] Some years, the maximum rate has reached 9–30 meteors per hour.[59]

The other meteor showers radiating from Auriga are far less prominent and capricious than the Alpha Aurigids. The Zeta Aurigids are a weak shower with a northern and southern branch lasting from December 11 to January 21. The shower peaks on January 1 and has very slow meteors, with a maximum rate of 1–5 meteors per hour. It was discovered by William Denning in 1886 and was discovered to be the source of rare fireballs by Alexander Hershel.[63] There is also another faint stream of meteors called the "Aurigids", unrelated to the September shower. This shower lasts from January 31 to February 23, peaking from February 5 through February 10; its slow meteors peak at a rate of approximately 2 per hour.[64] The Delta Aurigids are another faint shower radiating from Auriga. It was discovered by a group of researchers at New Mexico State University and has a very low peak rate. The Delta Aurigids last from September 22 through October 23, peaking between October 6 and October 15.[65] They may be related to the September Perseids, though they are more similar to the Coma Berenicids in that the Delta Aurigids last longer and have a dearth of bright meteors.[66] They also have a hypothesized connection to an unknown short period retrograde comet.[67] The Iota Aurigids are a hypothesized shower occurring in mid-November; its parent body may be the asteroid 2000 NL10, but this connection is highly disputed. The hypothesized Iota Aurigids may instead be a faint stream of Taurids.[68]

References

Citations

- ^ Russell, Henry Norris (1922). "The New International Symbols for the Constellations". Popular Astronomy. 30: 469. Bibcode:1922PA.....30..469R.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Pasachoff 2006.

- ^ Ridpath, Ian. "Constellations". Retrieved 23 June 2012.

- ^ Bakich 1995, p. 54.

- ^ Bakich 1995, p. 26.

- ^ "The 100 Nearest Star Systems". Research Consortium on Nearby Stars. 1 January 2012. Retrieved 23 June 2012.

- ^ Rogers, John H. (1998). "Origins of the Ancient Constellations: I. The Mesopotamian Traditions". Journal of the British Astronomical Association. 108 (1): 9–28. Bibcode:1998JBAA..108....9R.

- ^ Rogers, John H. (1998). "Origins of the Ancient Constellations: II. The Mediterranean Traditions". Journal of the British Astronomical Association. 108 (2): 79–89. Bibcode:1998JBAA..108...79R.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o Moore & Tirion 1997.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Ridpath & Tirion 2009, p. 67.

- ^ a b c d e Ridpath, Ian. "Auriga". Star Tales. Retrieved 4 July 2012.

- ^ Krupp, E.C. (May 2007). "Rambling through the stars: Designated driver". Sky & Telescope: 39–40.

- ^ Staal 1988, p. 79.

- ^ a b Winterburn 2009, p. 131.

- ^ Staal 1988, p. 109.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t Ridpath & Tirion 2001, pp. 86–88.

- ^ a b Allen 1899, pp. 83–91.

- ^ a b Olcott 2004, pp. 65–69.

- ^ Staal 1988, p. 29.

- ^ Ridpath, Ian (1988). "Telescopium Herschelii". Star Tales. Retrieved 16 July 2012.

- ^ Bakich 1995, p. 11.

- ^ Pasachoff 2006, pp. 128–129.

- ^ Russell, Henry Norris (1922). "The New International Symbols for the Constellations". Popular Astronomy. 30: 469–471. Bibcode:1922PA.....30..469R.

- ^ "Auriga constellation boundary". The Constellations. International Astronomical Union. Retrieved 4 July 2012.

- ^ Staal 1988, p. 70.

- ^ Staal 1988, pp. 221–222.

- ^ "Alpha Aurigae". SIMBAD. Retrieved 26 June 2012.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa Burnham 1978, pp. 261–296.

- ^ a b Davis Jr., George A. (1944). "The Pronunciations, Derivations, and Meanings of a Selected List of Star Names". Popular Science.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae Moore 2000, pp. 338–340.

- ^ Moore 2000, p. 279.

- ^ "Iota Aurigae". SIMBAD. Retrieved 26 June 2012.

- ^ "Delta Aurigae". SIMBAD. Retrieved 27 June 2012.

- ^ "Lambda Aurigae". SIMBAD. Retrieved 26 June 2012.

- ^ "Nu Aurigae". SIMBAD. Retrieved 27 June 2012.

- ^ "Tau Aurigae". SIMBAD. Retrieved 27 June 2012.

- ^ "Upsilon Aurigae". SIMBAD. Retrieved 27 June 2012.

- ^ "Pi Aurigae". SIMBAD. Retrieved 27 June 2012.

- ^ "Kappa Aurigae". SIMBAD. Retrieved 27 June 2012.

- ^ "Omega Aurigae". SIMBAD. Retrieved 27 June 2012.

- ^ "2 Aurigae". SIMBAD. Retrieved 27 June 2012.

- ^ "9 Aurigae". SIMBAD. Retrieved 27 June 2012.

- ^ "Mu Aurigae". SIMBAD. Retrieved 27 June 2012.

- ^ "Sigma Aurigae". SIMBAD. Retrieved 27 June 2012.

- ^ "Xi Aurigae". SIMBAD. Retrieved 27 June 2012.

- ^ "Epsilon Aurigae". SIMBAD. Retrieved 26 June 2012.

- ^ "Zeta Aurigae". SIMBAD. Retrieved 26 June 2012.

- ^ "Eta Aurigae". SIMBAD. Retrieved 26 June 2012.

- ^ "Psi1 Aurigae". SIMBAD. Retrieved 27 June 2012.

- ^ a b Harrington, Phil (1992). David J. Eicher (ed.). "The Challenge of Winter Nebulae". Astronomy. Kalmbach Publishing Co. ISBN 0-913135-05-4.

- ^ "Theta Aurigae". SIMBAD. Retrieved 27 June 2012.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o Thompson & Thompson 2007, pp. 94–101.

- ^ Fekel, Francis C.; Tomkin, Jocelyn (2007). "Spectroscopic Binary Candidates for Interferometers". In Hartkopf, William I.; Guinan, Edward F.; Harmanec, Petr (eds) (ed.). Binary Stars as Critical Tools and Tests in Contemporary Astrophysics: Proceedings of the 240th Symposium of the International Astronomical Union Held in Prague, Czech Republic, August 22-25, 2006. Cambridge University Press. pp. 59–60. ISBN 0521863481.

{{cite book}}:|editor=has generic name (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "HR 1528". SIMBAD. Retrieved 17 July 2012.

- ^ Crossen & Rhemann 2004, p. 177.

- ^ a b Higgins, David (1992). David J. Eicher (ed.). "The Ghostly Glow of Gaseous Nebulae". Astronomy. Kalmbach Publishing Co. ISBN 0-913135-05-4.

{{cite journal}}: More than one of|work=and|journal=specified (help) - ^ a b Jenniskens 2006, pp. 175–178.

- ^ a b Jenniskens 2006, p. 82.

- ^ a b Levy 2008, pp. 117–118.

- ^ Jenniskens, Peter; Kemp, Christopher C. (11 December, 2007). "Aurigids". Ames Research Center & Seti Institute. Retrieved 20 June 2012.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Lunsford, Robert (25 August 2011). "Meteor Activity Outlook for August 27- September 2, 2011". American Meteor Society. Retrieved 20 June 2012.

- ^ Lunsford, Robert (16 January 2012). "2012 Meteor Shower List". American Meteor Society. Retrieved 20 June 2012.

- ^ Levy 2008, pp. 103–104.

- ^ Levy 2008, p. 106.

- ^ Levy 2008, p. 119.

- ^ Dubietis, Audrius; Arlt, Rainer (October 2002). "The current Delta-Aurigid meteor shower". WGN, Journal of the International Meteor Organization. 30 (5): 168–174. Bibcode:2002JIMO...30..168D.

- ^ Drummond, Jack D. (September 1982). "A note on the Delta Aurigid meteor stream". Icarus. 51 (3): 655–659. doi:10.1016/0019-1035(82)90153-1. Retrieved 20 June 2012.

- ^ Meng, H. (October 2002). "Activity of Iota-Aurigids in 2001 and the possible orbit of the meteoroid stream". WGN, Journal of the International Meteor Organization. 30 (5): 175–180. Bibcode:2002JIMO...30..175M.

References

- Allen, Richard Hinckley (1899). "Star Names: Their Lore and Meaning" (Document). Dover.

{{cite document}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Bakich, Michael E. (1995). The Cambridge Guide to the Constellations. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-44921-2.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Burnham, Robert, Jr. (1978). Burnham's Celestial Handbook (2nd ed.). Dover Publications. ISBN 0-486-24063-0.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Crossen, Craig; Rhemann, Gerald (2004). Sky vistas: astronomy for binoculars and richest-field telescopes. Springer. ISBN 3-211-00851-9.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Jenniskens, Peter (2006). Meteor Showers and their Parent Comets. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-85349-1.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Levy, David H. (2008). David Levy's Guide to Observing Meteor Showers. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-69691-3.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Moore, Patrick; Tirion, Wil (1997). Cambridge Guide to Stars and Planets (2nd ed.). Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-58582-1.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Moore, Patrick (2000). The Data Book of Astronomy. Institute of Physics Publishing. ISBN 0-7503-0620-3.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Olcott, William Tyler (2004). Star Lore: Myths, Legends, and Facts. Courier Dover Publications. ISBN 978-0-486-43581-7.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Pasachoff, Jay M. (2006). Stars and Planets. Maps and charts by Wil Tirion (4th ed.). Houghton Mifflin. ISBN 978-0-395-93432-6.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Ridpath, Ian; Tirion, Wil (2001). Stars & Planets (3rd ed.). Princeton University Press. ISBN 0-691-08913-2.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Ridpath, Ian (2007). Stars and Planets Guide. Wil Tirion (4th ed.). Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-13556-4.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Ridpath, Ian; Tirion, Wil (2009). The Monthly Sky Guide (8th ed.). Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-13369-2.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Thompson, Robert Bruce; Thompson, Barbara Fritchman (2007). Illustrated Guide to Astronomical Wonders. O'Reilly Media. ISBN 978-0-596-52685-6.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Winterburn, Emily (2009). The Stargazer's Guide: How to Read Our Night Sky. Harper Perennial. ISBN 978-0-06-178969-4.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)