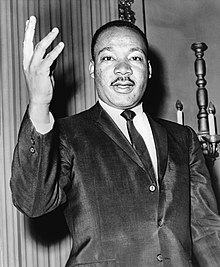

Assassination of Martin Luther King Jr.

| Assassination of Martin Luther King, Jr. | |

|---|---|

Martin Luther King, Jr. | |

| Location | Memphis, Tennessee |

| Date | April 4, 1968 6:01 p.m. (Central Time) |

| Target | Martin Luther King, Jr. |

| Weapons | Remington 760 Gamemaster |

| Perpetrators | James Earl Ray according to a criminal case; Loyd Jowers & "unknown co-conspirators" according to a later civil case |

Martin Luther King, Jr. was an American clergyman, activist, and prominent leader of the African-American civil rights movement and Nobel Peace Prize laureate who became known for his advancement of civil rights by using civil disobedience. He was assassinated at the Lorraine Motel in Memphis, Tennessee on April 4, 1968, at the age of 39. King was rushed to St. Joseph's Hospital, where he was pronounced dead at 7:05PM that evening. James Earl Ray, a fugitive from the Missouri State Penitentiary, was arrested in London at Heathrow Airport, extradited to the United States, and charged with the crime. On March 10, 1969, Ray entered a plea of guilty and was sentenced to 99 years in the Tennessee state penitentiary.[1] Ray later made many attempts to withdraw his guilty plea and be tried by a jury, but was unsuccessful; he died in prison on April 23, 1998, at the age of 70.[2]

Background

King on death

King received death threats constantly due to his prominence in the civil rights movement. As a consequence of these threats, he confronted death constantly, making it a central part of his philosophy. He believed, and taught, that murder could not stop the struggle for equal rights. After the 1963 JFK assassination, he told his wife Coretta: "This is what is going to happen to me also. I keep telling you, this is a sick society."[3][4]

Memphis

King traveled to Memphis, Tennessee in support of striking African American sanitation workers. The workers had staged a walkout on February 11, 1968, to protest unequal wages and working conditions. At the time, Memphis paid black workers significantly lower wages than whites. In addition, unlike their white counterparts, blacks received no pay if they stayed home during bad weather; consequently, most blacks were compelled to work even in driving rain and snow storms.[5][6][7]

On April 3, King returned to Memphis to address a gathering at the Mason Temple (World Headquarters of the Church of God in Christ). His airline flight to Memphis was delayed by a bomb threat against his plane.[8][9] With a thunderstorm raging outside, King delivered the last speech of his life, now known as the "I've Been to the Mountaintop" address. As he neared the close, he made reference to the bomb threat:

And then I got to Memphis. And some began to say the threats... or talk about the threats that were out. What would happen to me from some of our sick white brothers? Well, I don't know what will happen now. We've got some difficult days ahead. But it doesn't matter with me now. Because I've been to the mountaintop. [applause] And I don't mind. Like anybody, I would like to live a long life. Longevity has its place. But I'm not concerned about that now. I just want to do God's will. And He's allowed me to go up to the mountain. And I've looked over. And I've seen the promised land. I may not get there with you. But I want you to know tonight, that we, as a people, will get to the promised land! [applause] And so I'm happy, tonight. I'm not worried about anything. I'm not fearing any man. Mine eyes have seen the glory of the coming of the Lord![10]

Assassination

King was booked in room 306 at the Lorraine Motel in Memphis, owned by businessman Walter Bailey (and named after his wife). King's close friend and colleague Reverend Ralph David Abernathy, who was King's roommate in the motel room the day of the assassination, told the House Select Committee on Assassinations that King and his entourage stayed in room 306 at the Lorraine Motel so often that it was known as the "King-Abernathy Suite."[11]

According to biographer Taylor Branch, King's last words were to musician Ben Branch, who was scheduled to perform that night at an event King was going to attend: "Ben, make sure you play 'Take My Hand, Precious Lord' in the meeting tonight. Play it real pretty."[12]

At 6:01 p.m. on Thursday, April 4, 1968, while he was standing on the motel's second floor balcony, King was struck by a single .30 bullet fired from a Remington 760 Gamemaster.[13] The bullet entered through his right cheek, breaking his jaw, neck and several vertebrae as it travelled down his spinal cord, severing the jugular vein and major arteries in the process before lodging in his shoulder, King's necktie was ripped completely off his shirt. He fell violently backwards onto the balcony unconscious. Shortly after the shot was fired, witnesses saw James Earl Ray fleeing from a rooming house across the street from the Lorraine Motel where he was renting a room. A package was dumped close to the site that included a rifle and binoculars with Ray's fingerprints on them. The rifle had been purchased by Ray under an alias six days before. A worldwide manhunt was triggered that culminated in the arrest of Ray at London Heathrow Airport two months later.[14]

Abernathy heard the shot from inside the motel room and ran to the balcony to find King on the floor. King's eyes were closed, and he was bleeding profusely from the wound in his cheek.[13][15]King had no pulse and Young believed he was dead. Abernathy managed to stop the bleeding and King's pulse was heard again.

The unconscious King was rushed to St. Joseph's Hospital, where doctors opened his chest and performed manual heart massage. He never regained consciousness and was pronounced dead at 7:05 p.m. According to Taylor Branch, King's autopsy revealed that though he was only 39 years old, he had the heart of a 60 year old man.[16]

Responses

Within the movement

For some, King's assassination meant the end of a strategy of non-violence.[17]

Others simply reaffirmed the need to carry on his work. Leaders within the SCLC confirmed that they would carry on this Poor People's Campaign in his absence.[18] Some black leaders argued the need to continue King's tradition of nonviolence.[17]

Robert F. Kennedy speech

A speech on the assassination of Martin Luther King, Jr. was given on April 4, 1968, by New York Senator Robert F. Kennedy (who was assassinated two months later). Kennedy was campaigning for the 1968 Democratic presidential nomination and had spoken at the University of Notre Dame and Ball State University earlier that day.[19] Before boarding a plane to fly to Indianapolis for one last campaign speech in a predominantly black neighborhood of the city he learned that Martin Luther King had been shot, leading Kennedy press secretary Frank Mankiewicz to suggest that he ask the audience to pray for the King family and ask them to follow King's deeply-held belief in non-violence.[20] They did not learn that King was dead until they landed in Indianapolis.

Both Mankiewicz and speechwriter Adam Walinsky drafted notes immediately before the rally for Kennedy's use, but Kennedy refused Walinsky's notes, instead using some that he had likely[dubious – discuss] written on the ride over; Mankiewicz arrived after Kennedy had already begun to speak.[21] Prior to arriving at the rally, the Chief of Police in Indianapolis told Kennedy that he could not provide protection and that giving the remarks would be too dangerous,[22] but Kennedy decided to go ahead regardless. Standing on a podium mounted on a flatbed truck, Kennedy spoke for just four minutes and fifty-seven seconds.[23]

Robert F. Kennedy was the first to inform the audience of the death of Martin Luther King, causing some in the audience to scream and wail. Several of Kennedy's aides were even worried that the delivery of this information would result in a riot.[24] Once the audience quieted down, Kennedy acknowledged that many in the audience would be filled with anger. But then Kennedy went on: "For those of you who are black and are tempted to fill with -- be filled with hatred and mistrust of the injustice of such an act, against all white people, I would only say that I can also feel in my own heart the same kind of feeling. I had a member of my family killed, but he was killed by a white man." These remarks surprised Kennedy aides, who had never heard him speak publicly of John F. Kennedy's death.[25] Kennedy continued, saying that the country had to make an effort to "go beyond these rather difficult times," and then quoted a poem by the Greek playwright Aeschylus, on the theme of the wisdom that comes, against one's will, from pain. To conclude, Kennedy said that the country needed and wanted unity between blacks and whites, asked the audience members to pray for the King family and the country, and once more quoted the ancient Greeks.

The speech was credited in part with preventing post-assassination rioting in Indianapolis where it was given, though there were riots in many other parts of the country.[26] It is widely considered one of the most important speeches in American history.[27]

President Johnson

President Lyndon Johnson was in the Oval Office, planning a consultation in Hawaii with Vietnam War military commanders. After press secretary George Christian informed him of the assassination at 8:20PM, he canceled the trip to Hawaii and turned his attention homeward. He assigned Attorney General Ramsey Clark to investigate the assassination in Memphis. He also made a personal call to Dr. King's wife, Coretta Scott King.[28]

White America

In the wake of King's death, journalists reported callous or hostile reactions from many parts of white America, particularly in the south. Journalist David Halberstam, who reported on King's funeral, recounted a comment at an affluent white dinner party: "One of the wives—station wagon, three children, forty-five-thousand-dollar house—leaned over and said, 'I wish you had spit in his face for me.' It was a stunning moment; I wondered for a long time afterwards what King could possibly have done to her, in what conceivable way he could have threatened her, why this passionate hate."[29]

On the other hand, a survey sent to a group of college trustees revealed that their opinions of King had increased after his assassination.[3]

An editorial in the New York Times praised King, called his murder a "national disaster" and his cause "just."[30][31]

Public figures generally praised King. Even George Wallace, a notorious segregationist, described the assassination as a "senseless, regrettable act."[17]

Riots

Colleagues of Dr. King in the civil rights movement called for a non-violent response to the assassination, to honor his most deeply-held beliefs. James Farmer, Jr. said:

"Dr. King would be greatly distressed to find that his blood had triggered off bloodshed and disorder... I think instead the nation should be quiet; black and white, and we should be in a prayerful mood, which would be in keeping with his life. We should make that kind of dedication and commitment to the goals which his life served to solving the domestic problems. That's the memorial, that's the kind of memorial we should build for him. It's just not appropriate for there to be violent retaliations, and that kind of demonstration in the wake of the murder of this pacifist and man of peace."[32]

The more militant Stokely Carmichael, however, called for more forceful action, saying:

"White America killed Dr. King last night. She made a whole lot easier for a whole lot of black people today. There no longer needs to be intellectual discussions, black people know that they have to get guns. White America will live to cry that she killed Dr. King last night. It would have been better if she had killed Rap Brown and/or Stokley Carmichael, but when she killed Dr. King, she lost."[32]

Despite the urging of many leaders, the assassination led to a nationwide wave of riots in more than 100 cities.[33] After the assassination, the city of Memphis quickly settled the strike on favorable terms to the sanitation workers.[34][35]

Washington, D.C.

The Washington, D.C. riots of April 4–8, 1968, affected at least 110 U.S. cities; Washington, along with Chicago and Baltimore, was among the most impacted.

The ready availability of jobs in the growing federal government attracted many to Washington in the 1960s, and middle class African-American neighborhoods prospered. Despite the end of legally mandated racial segregation, the historic neighborhoods of Shaw, the H Street Northeast corridor, and Columbia Heights, centered at the intersection of 14th and U Streets Northwest, remained the centers of African-American commercial life in the city.

As word of King's murder by James Earl Ray in Memphis spread on the evening of Thursday, April 4, crowds began to gather at 14th and U. Stokely Carmichael led members of the SNCC to stores in the neighborhood demanding that they close out of respect. Although polite at first, the crowd fell out of control and began breaking windows. By 11pm, widespread looting had begun, as well as in over 30 other cities.

Mayor-Commissioner Walter Washington ordered the damage cleaned up immediately the next morning. However, anger was still evident on Friday morning when Carmichael addressed a rally at Howard. He warned of violence and after the close of the rally, crowds walking down 7th Street NW and in the H Street NE corridor, came into violent confrontations with police. By midday, numerous buildings were on fire, and firefighters were prevented from responding by crowds attacking with bottles and rocks.

Crowds of as many as 20,000 overwhelmed the District's 3,100-member police force, and President Lyndon B. Johnson dispatched some 13,600 federal troops, including 1,750 federalized D.C. National Guard troops to assist them. Marines mounted machine guns on the steps of the Capitol and Army troops from the 3rd Infantry guarded the White House. At one point, on April 5, rioting reached within two blocks of the White House before rioters retreated. The occupation of Washington was the largest of any American city since the Civil War. Mayor Washington imposed a curfew and banned the sale of alcohol and guns in the city. By the time the city was considered pacified on Sunday, April 8, twelve had been killed (mostly in burning homes), 1,097 injured, and over 6,100 arrested[citation needed]. Additionally, some 1,200 buildings had been burned, including over 900 stores. Damages reached $27 million. This can be estimated to be equivalent to over $156 million today[citation needed].

The riots utterly devastated Washington's inner city economy. With the destruction or closing of businesses, thousands of jobs were lost, and insurance rates soared. Made uneasy by the violence, city residents of all races accelerated their departure for suburban areas, depressing property values. Crime in the burned out neighborhoods rose sharply, further discouraging investment.

On some blocks, only rubble remained for decades. Columbia Heights and the U Street corridor did not begin to recover economically until the opening of the U Street and Columbia Heights Metro stations in 1991 and 1999, respectively, while the H Street NE corridor remained depressed for several years longer.

Mayor-Commissioner Washington, who reportedly refused[citation needed] FBI director J. Edgar Hoover's suggestion to shoot the rioters, went on to become the city's first elected mayor.

Baltimore

The Baltimore Riot of 1968 began the day after the murder. On Saturday, April 6, the Governor of Maryland, Spiro T. Agnew, called out thousands of National Guard troops and 500 Maryland State Police to quell the disturbance. When it was determined that the state forces could not control the riot, Agnew requested Federal troops from President Lyndon B. Johnson. There is some debate about whether or not this riot should be called a "riot," a "civil disturbance," or a "rebellion".[citation needed] These events were indeed precipitated by King's assassination, but were also evidence of larger frustrations among the city's African-American population.

By Sunday evening, 5000 paratroopers, combat engineers, and artillerymen from the XVIII Airborne Corps in Fort Bragg, North Carolina, specially trained in tactics, including sniper school, were on the streets of Baltimore with fixed bayonets, and equipped with chemical (CS) disperser backpacks. Two days later, they were joined by a Light Infantry Brigade from Fort Benning, Georgia. With all the police and troops on the streets, things began to calm down. The Federal Bureau of Investigation reported that H. Rap Brown was in Baltimore driving a Ford Mustang with Broward County, Florida tags, and was assembling large groups of angry protesters and agitating them to escalate the rioting. In several instances, these disturbances were rapidly quelled through the use of bayonets and chemical dispersers by the XVIII Airborne units. That unit arrested more than 3,000 detainees, who were turned over to the Baltimore Police. A general curfew was set at 6 p.m. in the city limits and martial law was enforced. As rioting continued, African American plainclothes police officers and community leaders were sent to the worst areas to prevent further violence.

By the time the riot was over, 6 people would be dead, 700 injured, 4,500 arrested and over 1,000 fires set. More than a thousand businesses had been looted or burned, many of which never reopened. Total property damage was estimated at $13.5 million (1968$).

One of the major outcomes of the riot was the attention Spiro Agnew received when he criticized local black leaders for not doing enough to help stop the disturbance. While this angered blacks and white liberals, it caught the attention of Richard Nixon who was looking for someone on his ticket who could counter George Wallace’s American Independent Party campaign. Agnew became Nixon’s Vice Presidential running mate in 1968.

Louisville

The Louisville riots of 1968 refers to riots in Louisville, Kentucky in May 1968. As in many other cities around the country, there were unrest and riots partially in response to the assassination. On May 27, 1968, a group of 400 people, mostly blacks, gathered at Twenty-Eight and Greenwood Streets, in the Parkland neighborhood. The intersection, and Parkland in general, had recently become an important location for Louisville's black community, as the local NAACP branch had moved its office there.

The crowd was protesting the possible reinstatement of a white officer who had been suspended for beating an African-American man some weeks earlier. Several community leaders arrived and told the crowd that no decision had been reached, and alluded to disturbances in the future if the officer was reinstated. By 8:30, the crowd began to disperse.

However, rumors (which turned out to be untrue) were spread that Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee speaker Stokely Carmichael's plane to Louisville was being intentionally delayed by whites. After bottles were thrown by the crowd, the crowd became unruly and police were called. However the small and unprepared police response simply upset the crowd more, which continued to grow. The police, including a captain who was hit in the face by a bottle, retreated, leaving behind a patrol car, which was turned over and burned.

By midnight, rioters had looted stores as far east as Fourth Street, overturned cars and started fires.

Within an hour, Mayor Kenneth A. Schmied requested 700 Kentucky National Guard troops and established a city-wide curfew. Violence and vandalism continued to rage the next day, but had subdued somewhat by May 29. Business owners began to return, although troops remained until June 4. Police made 472 arrests related to the riots. Two African-American teenagers had died, and $200,000 in damage had been done.[36]

The disturbances had a longer-lasting effect. Most white business owners quickly pulled out or were forced out of Parkland and surrounding areas. Most white residents also left the West End, which had been almost entirely white north of Broadway, from subdivision until the 1960s. The riot would have effects that shaped the image which whites would hold of Louisville's West End, that it was predominantly black and crime-ridden.[37]

Kansas City

The rioting in Kansas City did not erupt on April 4, like other cities of the United States affected directly by the assassination of King, but rather on April 9 after local events within the city.[38][39] The riot was sparked when Kansas City Police Department deployed tear gas against student protesters when they staged their performances outside City Hall.[38][39] The deployment of tear gas dispersed the protesters from the area, but other citizens of the city began to riot as a result of the Police action on the student protesters. The resulting effects of the riot resulted in the arrest of over one hundred adults, and left five dead and at least twenty admitted to hospitals.[40]

Chicago

In Chicago, more than 48 hours of rioting left 11 Chicago citizens dead, 48 wounded by police gunfire, 90 policemen injured, and 2,150 people arrested.[41] Two miles of Lawndale on West Madison Street were left in a state of rubble.

FBI Investigation

The Federal Bureau of Investigation took responsibility for investigating King's death. J. Edgar Hoover, who had previously made efforts to undermine King's reputation, told Johnson that his agency would attempt to find the culprit(s).[28]

Funeral

President Lyndon B. Johnson declared April 7 a national day of mourning for the lost civil rights leader. A crowd of 300,000 attended his funeral two days later, on April 9.[28] Vice President Hubert Humphrey attended on behalf of Lyndon B. Johnson, who was at a meeting on the Vietnam War at Camp David. (There were fears that Johnson might be hit with protests and abuses over the war if he attended). At his widow's request, King eulogized himself: His last sermon at Ebenezer Baptist Church, a recording of his famous 'Drum Major' sermon, given on February 4, 1968, was played at the funeral. In that sermon he makes a request that at his funeral no mention of his awards and honors be made, but that it be said that he tried to "feed the hungry," "clothe the naked," "be right on the [Vietnam] war question," and "love and serve humanity." Per King's request, his good friend Mahalia Jackson sang his favorite hymn, "Take My Hand, Precious Lord" at his funeral. Rebecca Burns wrote about the funeral in Burial for a King.

James Earl Ray

Capture and guilty plea

Two months after King's death, escaped convict James Earl Ray was captured at London Heathrow Airport while trying to leave the United Kingdom for Angola, Rhodesia or South Africa[42] on a false Canadian passport in the name of Ramon George Sneyd.[43] Ray was quickly extradited to Tennessee and charged with King's murder, confessing to the assassination on March 10, 1969 (although he recanted this confession three days later).

On the advice of his attorney Percy Foreman, Ray took a guilty plea to avoid a trial conviction and thus the possibility of receiving the death penalty. Ray was sentenced to a 99-year prison term.[44]

Ray fired Foreman as his attorney (from then on derisively calling him "Percy Fourflusher") claiming that a man he met in Montreal, Canada with the alias "Raul" was involved, as was his brother Johnny, but not himself, further asserting through his attorney Jack Kershaw that although he did not "personally shoot King," he may have been "partially responsible without knowing it," hinting at a conspiracy.[45] He spent the remainder of his life attempting (unsuccessfully) to withdraw his guilty plea and secure the trial he never had. In 1997, Martin Luther King's son Dexter King met with Ray, and publicly supported Ray's efforts to obtain a retrial.[46]

Dr. William Pepper remained James Earl Ray's attorney until Ray's death and then carried on, on behalf of the King family. The King family does not believe Ray had anything to do with the murder of Martin Luther King.[47]

Escape

Ray and seven other convicts escaped from Brushy Mountain State Penitentiary in Petros, Tennessee, on June 10, 1977. They were recaptured on June 13, three days later, and returned to prison.[48] One more year was added to his previous sentence to total 100 years. Shortly after, Ray testified that he did not shoot King to the House Select Committee on Assassinations.

Death

Ray died in prison on April 23, 1998, at the age of 70 from complications related to kidney disease, caused by hepatitis C (probably contracted as a result of a blood transfusion given after a stabbing while at Brushy Mountain State Penitentiary). It was also confirmed in the autopsy that he died of liver failure.

Allegations of conspiracy

The King family and others believe that the assassination was carried out by a conspiracy involving the US government, and that James Earl Ray was a scapegoat. This conclusion was affirmed by a jury in a 1999 civil trial.[49]

In 2004, Jesse Jackson, who was with King at the time of his death, noted:

The fact is there were saboteurs to disrupt the march. [And] within our own organization, we found a very key person who was on the government payroll. So infiltration within, saboteurs from without and the press attacks. …I will never believe that James Earl Ray had the motive, the money and the mobility to have done it himself. Our government was very involved in setting the stage for and I think the escape route for James Earl Ray.[50]

According to biographer Taylor Branch, King's friend and colleague James Bevel put it more bluntly: "[T]here is no way a ten-cent white boy could develop a plan to kill a million-dollar black man."[51]

The impending occupation of Washington D.C. by the Poor People's Campaign is suggested as a primary motivate for a federal assassination.[49] Reverend James Lawson also noted during the civil trial that King alienated President Johnson and other powerful government actors when he repudiated the Vietnam War on April 4, 1967—exactly one year before the assassination.[52]

Ray as scapegoat

Some claim that Ray's confession was given under pressure, and that he had been threatened with the death penalty if he did not confess.[53][54]

Many suspecting a conspiracy in the assassination point out the two separate ballistic tests conducted on the Remington Gamemaster had neither conclusively proved Ray had been the killer nor that it had even been the murder weapon.[55][56] Moreover, witnesses surrounding King at the moment of the shooting say the shot was fired from a different location, from behind thick shrubbery near the rooming house, and not from the rooming house window.[57]

Civil case for conspiracy

In 1999, the King family conducted a civil case to consider the existence of an assassination conspiracy. The suit (for wrongful death) mentioned only Loyd Jowers, but also described a government conspiracy.[49]

The jury–six blacks and six whites—found that King had been the victim of assassination by a conspiracy involving the Memphis police as well as federal agencies. This verdict affirmed Ray's innocence, which the King family has always maintained.[58][52]William F. Pepper represented the King family in the trial.[59][60][61] The family requested a mere $100 in restitution to show that they were not pursuing the case for financial gain.

Denials of conspiracy

King biographer David Garrow disagrees with William F. Pepper's claims that the government killed King. He is supported by author Gerald Posner.[62]

In 2000, the Department of Justice completed the investigation about Jowers' claims but did not find evidence to support the allegations about conspiracy. The investigation report recommends no further investigation unless some new reliable facts are presented.[63]

Henry Clay Wilson theory

A church minister, Ronald Denton Wilson, claimed his father, Henry Clay Wilson, assassinated Martin Luther King, Jr., not James Earl Ray.[64] He stated, "It wasn't a racist thing; he thought Martin Luther King was connected with communism, and he wanted to get him out of the way." But Wilson had reportedly admitted previously that his father was a member of the Ku Klux Klan.[65]

References

- ^ Pepper, William F. (2008). An Act of State: The Execution of Martin Luther King. Verso. p. 8. ISBN 978-1-84467-285-1.

- ^ Pepper, William F. (2008). An Act of State: The Execution of Martin Luther King. Verso. p. 97. ISBN 978-1-84467-285-1.

- ^ a b Dyson, Michael Eric (2008). "Fighting Death". April 4, 1968 : Martin Luther King, Jr.'s death and how it changed America. New York: Basic Civitas Books. ISBN 978-0-465-00212-2.

- ^ "King had predicted he too would be killed". Washington Afro-American. 9 September 1969. Retrieved 20 July 2012.

- ^ "1,300 Members Participate in Memphis Garbage Strike". AFSCME. 1968-02-01. Archived from the original on 6 December 2006. Retrieved 2006-12-23.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Memphis Strikers Stand Firm". AFSCME. 1968-03-01. Archived from the original on 6 December 2006. Retrieved 2006-12-23.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Rugaber, Walter (March 29, 1968). "A Negro is Killed in Memphis". The New York Times. Retrieved 2006-12-23.

- ^ The Worst Week of 1968

- ^ Rosenberg, Jennifer. "Martin Luther King Jr. Assassinated". 20th Century History. About.com. Retrieved 20 July 2012.

- ^ "I've Been to the Mountaintop"

- ^ "United States Department of Justice Investigation of Recent Allegations Regarding the Assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr - VII. KING V. JOWERS CONSPIRACY ALLEGATIONS". United States Department of Justice. June 2000. Archived from the original on 15 July 2007. Retrieved 2007-07-21.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Branch, Taylor (2006). At Canaan's Edge: America in the King Years, 1965-68. America in the King Years. Simon & Schuster. p. 766. ISBN 0-684-85713-8.

- ^ a b Mark Gribben. "James Earl Ray: The Man Who Killed Dr. Martin Luther King". Retrieved 2011-02-05.

- ^ Martin Luther King, Jr: Assassination Conspiracy theories

- ^ "Assassination of Martin Luther King, Jr". Christian History Institute. March, 2007. Retrieved 2007-07-21.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help)[dead link] - ^ American Experience | Citizen King | Transcript | PBS

- ^ a b c "McKissick Says Nonviolence Has Become Dead Philosophy". New York Times. 5 April 1968.

{{cite news}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) Cite error: The named reference "NYTnonviolence" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page). - ^ "Aide to Dr. King Asserts March Of Poor in Capital Will Be Held". New York Times. 5 April 1968.

{{cite news}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ^ Klein, Joe. Politics Lost: How American Democracy was Trivialized by People Who Think You're Stupid. New York, Doubleday, 2006., p. 2.

- ^ Klein, 3.

- ^ Klein, 3, 4.

- ^ Scarborough Country

- ^ Klein, 1, 4.

- ^ Klein, Joe. "Pssst! Who's behind the decline of politics? Consultants., Time, April 9, 2006. Retrieved November 17, 2007.

- ^ Klein, 6.

- ^ Statement of Mayor Bart Peterson April 4, 2006 press release

- ^ "Top 100 American Speeches of the 20th Century". Retrieved 2009-08-30.

- ^ a b c Kotz, Nick (2005). "14. Another Martyr". Judgment days : Lyndon Baines Johnson, Martin Luther King Jr., and the laws that changed America. Boston: Houghton Mifflin. p. 415. ISBN 0-618-08825-3.

- ^ Dyson, Michael Eric (2008). "Facing Death". April 4, 1968 : Martin Luther King, Jr.'s death and how it changed America. New York: Basic Civitas Books. ISBN 978-0-465-00212-2.

- ^ "'The Need of All Humanity'". New York Times. 5 April 1968.

{{cite news}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ^ Catalyst (8 November 2005). "White America's reaction to the shooting of MLK?". Straight Dope. Retrieved 20 July 2012.

- ^ a b "1968 Year In Review, UPI.com"

- ^ "1968: Martin Luther King shot dead". On this Day. BBC. April 4, 1968. Retrieved 2006-09-17.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|year=/|date=mismatch (help); Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ "AFSCME Wins in Memphis". AFSCME. 1968-04-01. Archived from the original on 6 December 2006. Retrieved 2006-12-23.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "1968 Memphis Sanitation Workers' Strike Chronology". AFSCME. 1968. Archived from the original on 6 December 2006. Retrieved 2006-12-23.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Williams, Kenneth H. (1988). "Oh…It's Really Happening:" The Louisville Race Riot of 1968". Kentucky History Journal. 3: 57–58.

- ^ Louisville Survey:West Report. pp. 37–38.

- ^ a b Rhodes, Joel P. The Voice of Violence: Performative Violence as Protest in the Vietnam Era. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 21. ISBN 0-275-97055-8.

- ^ a b Burnes, Brian (2007-08-10). "Riots of 1968 were a watershed moment for KC". Kansas City Star. Archived from the original on 2008-04-09. Retrieved 2008-04-12.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ "Kansas City riots, April 1968". Kansas City Star. January 16, 2006. Retrieved 2008-04-12.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ "West Madison Street 1968". Associated Press. Retrieved May 17, 2011.

- ^ http://books.google.com/books?id=Gb2AwFMso9UC&pg=PA296&lpg=PA296&dq=%22james+earl+ray%22+angola+rhodesia&source=web&ots=PXCtNMafRF&sig=iBF3veEDQIZMCWWWbiJBP7MBA68&hl=en

- ^ Borrell, Clive (June 28, 1968). "Ramon Sneyd denies that he killed Dr King". The Times. London. p. 2. Retrieved January 13, 2009.

- ^ http://www.upi.com/Audio/Year_in_Review/Events-of-1969/Chappaquiddick/12303189849225-7/ "1969 Year in Review, UPI.com"

- ^ Martin, Douglas. "Jack Kershaw Is Dead at 96; Challenged Conviction in King’s Death", The New York Times, September 24, 2010. Accessed September 25, 2010.

- ^ "James Earl Ray, convicted King assassin, dies". US news. CNN. April 23, 1998. Archived from the original on 29 October 2006. Retrieved 2006-09-17.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ KING FAMILY STATEMENT ON THE JUSTICE DEPARTMENT "LIMITED INVESTIGATION" OF THE MLK ASSASSINATION The King Center

- ^ FIELD OFFICE ESTABLISHED Knoxville Field Office, FBI.

- ^ a b c Douglass, Jim (Spring 2000). "The Martin Luther King Conspiracy Exposed in Memphis". Probe Magazine. Retrieved 20 July 2012.

- ^ Goodman, Amy (January 15, 2004). "Jesse Jackson On "Mad Dean Disease," the 2000 Elections and Martin Luther King". Democracy Now!. Archived from the original on 17 September 2006. Retrieved 2006-09-18.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ At Canaan's Edge. Simon & Schuster. 2006. p. 770. ISBN 978-0-684-85712-1.

- ^ a b "Trial Transcript Volume XIV". verdict. The King Center. 2006. Archived from the original on 2007-03-17. Retrieved 2007-03-24.

- ^ "James Earl Ray Profile". africanaonline.com. 2006. Archived from the original on 2010-01-21. Retrieved 2006-12-23.

- ^ "The Martin Luther King Assassination". the Real History Archives. 2006. Archived from the original on 2010-08-17. Retrieved 2006-12-23.

- ^ "James Earl Ray Dead At 70". CBS. April 23, 1998. Archived from the original on 12 December 2006. Retrieved 2006-12-23.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Questions left hanging by James Earl Ray's death". BBC. April 23, 1998. Retrieved 2006-12-23.

- ^ "Martin Luther King - Sniper in the Shrubbery?". africanaonline.com. 2006. Archived from the original on 2009-06-06. Retrieved 2006-12-23.

- ^ Kevin Sack and Emily Yellin (December 10, 1999). "Dr. King's Slaying Finally Draws A Jury Verdict, but to Little Effect". The New York Times.

- ^ "Text of the King family's suit against Loyd Jowers and Martin Luther King Jr.'s "unknown" conspirators". Court TV. 1999. Retrieved 2006-09-17.

- ^ Pepper, Bill (April 7, 2002). "William F. Pepper on the MLK Conspiracy Trial" (PDF). Rat Haus Reality Press. Archived from the original (PDF) on 21 September 2006. Retrieved 2006-09-17.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Trial Information". Complete Transcript of the Martin Luther King, Jr. Assassination Conspiracy Trial. The King Center. 2006. Archived from the original on 2006-06-28. Retrieved 2006-09-17.

- ^ Ayton, Mel (February 28, 2005). "Book review A Racial Crime: The Assassination of MLK". History News Network. Retrieved 2006-09-18.

- ^ "USDOJ Investigation of Recent Allegations Regarding the Assassination of Martin Luther King, Jr". Overview. USDOJ. June 2000. Archived from the original on 6 October 2006. Retrieved 2006-09-18.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Canedy, Dana (April 6, 2002). "A Minister Says His Father, Now Dead, Killed Dr. King". The New York Times. Retrieved 2009-12-29.

- ^ Canedy, Dana (April 6, 2002). "My father killed King, says pastor, 34 years on". The Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved 2006-09-18.

External links

- Department of Justice investigation on assassination

- Congressional Report on King's assassination

- Shelby County Register of Deeds documents on the Assassination Investigation

- Donald E. Wilkes Jr, Death of MLK Still a Mystery (1987).

- Donald E. Wilkes Jr, What are Facts of MLK Murder? (1987).