Hegemony

| Part of the Politics series |

| Basic forms of government |

|---|

| List of countries by system of government |

|

|

Hegemony (UK: /h[invalid input: 'ɨ']ˈɡɛməni/, US: /ˈhɛdʒ[invalid input: 'ɨ']moʊni/, US: /h[invalid input: 'ɨ']ˈdʒɛməni/; Template:Lang-el, "leadership", "rule") is an indirect form of government of imperial dominance in which the hegemon (leader state) rules geopolitically subordinate states by the implied means of power, the threat of force, rather than by direct military force.[1] In Ancient Greece (8th c. BC – AD 6th c.), hegemony denoted the politico–military dominance of a city-state over other city-states.[2] In the 19th century, hegemony denoted the geopolitical and the cultural predominance of one country upon others; from which derived hegemonism, the Great Power politics meant to establish European hegemony upon continental Asia and Africa.[3] In the 20th-century, Antonio Gramsci developed the philosophy and the sociology of geopolitical hegemony into the theory of cultural hegemony, whereby one social class can manipulate the system of values and mores of a society, in order to create and establish a ruling-class Weltanschauung, a worldview that justifies the status quo of bourgeois domination of the other social classes of the society.[2][4][5][6]

In the praxis of hegemony, imperial dominance is established by means of cultural imperialism, whereby the leader state (hegemon) dictates the internal politics and the societal character of the sub-ordinate states that constitute the hegemonic sphere of influence; either by an internal, sponsored government or by an external, installed government. The imposition of the hegemon’s way of life — an imperial lingua franca and bureaucracies (social, economic, educational, governing) — transforms the concrete imperialism of direct military domination into the abstract power of the status quo, indirect imperial domination.[1] Under hegemony, rebellion (social, political, economic, armed) is eliminated either by co-optation of the rebels or by suppression (police and military), without direct intervention by the hegemon; the examples are the latter-stage Spanish and British empires, and the 19th- and 20th-century reichs of unified Germany (1871–1945).[7]

History

- Antiquity

In the Græco–Roman world of 5th-century European Classical antiquity, the city-state of Sparta was the hegemon of the Peloponnesian League (6th – 4th centuries BC) and King Philip II of Macedon was the hegemon of the League of Corinth in 337 BC (a kingship he willed to his son, Alexander the Great). In Ancient Eastern Asia, Chinese hegemony was present during the Spring and Autumn Period (ca. 770–480 BC), when the weakened rule of the Eastern Zhou Dynasty led to the relative autonomy of the Five Hegemons (Ba in Chinese [霸]). They were appointed by feudal lord conferences, and thus were nominally obliged to uphold the imperium of the Zhou Dynasty over the sub-ordinate states. In late-16th– and early-17th-century Japan, the term hegemon applied to its "Three Unifiers" — Oda Nobunaga, Toyotomi Hideyoshi, and Tokugawa Ieyasu — who ruled most of the country by hegemony.

The etymological and theoretical underpinnings of hegemony trace back to Ancient Greece. The word hegemony is derived from the Greek word egemonia, meaning “leader, ruler, often in the sense of a state other than his own.” In the context of Ancient Greece, the term “hegemony” is a military-political hierarchy, as opposed to economic or cultural hegemony that emerges as a concept in the late 19th century. For Greeks, a hegemon was a “leader or leading state of a group of societies or states.” Greek historians Herodotus, Thucydides, Xenophon, and Ephorus wrote that Sparta and Athens both exhibited behaviors of a hegemon in different periods of their histories. Herodotus observed this influence that Sparta was exercising hegemonic powers and notable influence outside its own territories in organizing a Greek coalition to meet the invasion of Xerxes’ Persian armies in 480 BC. Herodotus noted Athens’ “willingness to give way on its command of the sea,” and put its navy under a Spartan commander, explaining this as “willingness of allies to take orders from the hegemon.” Thucydides said of the same coalition against Xerxes, “while in great peril hung over Greece, the Spartans, being superior in power, were the leaders of the United Greeks.” The Spartans’ superior power actively convinced Athens to accept Spartan rule, as opposed to Athens submitting to Sparta’s will as if they were a conquered territory. Thus, the Ancient Greek interpretation of what constituted a hegemon was not a universal power exerting total control over other actors, but rather a “unipolar influence structure.”

- Middle Ages and Renaissance

As a universal, politico–cultural hegemonic practice, the cultural institutions of the hegemon establish and maintain the political annexation of the subordinate peoples; in Italy, the Medici maintained their medieval Tuscan hegemony, by controlling the production of woolens by controlling the Arte della Lana guild, in the Florentine city-state. In Holland, the Dutch Republic’s 17th-century (1609–1672) mercantilist dominion was a first instance of global, commercial hegemony, made feasible with its technological development of wind power and its Four Great Fleets[citation needed], for the efficient production and delivery of goods and services, which, in turn, made possible its Amsterdam stock market and concomitant dominance of world trade; in France, King Louis XIV (1638–1715) and (Emperor) Napoleon I (1799–1815) established French hegemony via economic, cultural, and military domination of most of Continental Europe. After the defeat and exile of Napoleon, hegemony largely passed to the British Empire, which became the largest empire in world history, with Queen Victoria (1837-1901) ruling over one-quarter of the world's land and population at the zenith of the empire's existence. Like the Dutch, the British Empire was primarily seaborne; many British possessions were located around the rim of the Indian Ocean, as well as numerous islands in the Pacific Ocean and the Caribbean Sea. Britain also controlled large portions of Africa, as well as the entire Indian subcontinent.

- 20th century

The USSR (1922–1991), Nazi Germany (1933–1945), and the USA (1823–present) each sought regional hegemony (sphere of influence), then global hegemony.[8] In 1939, Nazi Germany launched the Second World War (1939–1945) to gain geographic dominance of Eurasia and Africa, initially, by means of empire (direct control), then by hegemony (indirect control). Afterwards, in 1945, the USA and the USSR fought the Cold War (1945–1991) for control of the global European empires of France, Britain, the Netherlands, et al., which were politically destroyed by the global warfare of the Second World War.

The roots of modern concepts of hegemony are founded in influential thinkers including Machiavelli, Marx, Lenin, and perhaps most notably, Antonio Gramsci. While neither Karl Marx nor Vladimir Lenin specifically wrote on the term hegemony, both utilized the concept of hegemony in their writings on the class structure of society. More specifically, Lenin wrote about the “leadership exercised by the proletariat over the other exploited classes.” His 1902 pamphlet, “What is to be done?” on the struggles of the working class cites the concept of gegemoniya, roughly translating to “political predominance, usually of one state over the other.” This concept gained more influence leading up to the Bolshevik Revolution in 1917. Lenin, “advocating strategies mirrored…in concepts of hegemony,” argued that the Bolsheviks had “a bounden duty in the struggle to overthrow autocracy” by “guiding activities” of opposition in tandem with garnering support from urban proletariats. Much like Greek interpretations of hegemony, Lenin’s use of gegemoniya did not connote absolute control over another party, but rather influence and the ability to “guide activities” of another party.

In the mid-20th century, the hegemonic conflict was ideologic, between the Communist Warsaw Pact (1955–1991) and the capitalist NATO (1949-present), wherein each hegemon competed directly (the arms race) and indirectly (proxy wars) against any country whose internal, national politics might destabilise the respective hegemony. The USSR defeated the nationalist Hungarian Revolution of 1956, and the USA precipitated the US–Vietnam War (1965–1975) by participating in the Vietnamese Civil War (1955–1965) that the National Liberation Front fought against the Republic of Vietnam, the Asian client state of the United States.[9]

- 21st century

In the post–Cold War (1945–1991) world, the French Socialist politician Hubert Védrine described the USA as a hegemonic hyperpower, because of its unilateral military actions worldwide, especially against Iraq; while the US political scientists John Mearsheimer and Joseph Nye counter that the USA is not a true hegemon because it has neither the financial nor the military resources to impose a proper, formal, global hegemony.[10]

Geography

The Neo-Marxist Henri Lefebvre proposes that geographic space is not a passive locus of social relations, but that it is trialectical — human geography is constituted by mental space, social space, and physical space — hence, hegemony is a spatial process influenced by geopolitics. In the ancient world, hydraulic despotism was established in the fertile river valleys of Egypt, China, and Mesopotamia. In China, during the Warring States Era (476–221 BC), the Qin State created the Chengkuo Canal for geopolitical advantage over its local rivals. In Eurasia, successor state hegemonies were established in the Middle East, using the sea (Greece) and the fringe lands (Persia, Arabia). European hegemony moved westwards, to Rome (27 BC – AD 476/145), then northwards, to the Holy Roman Empire (962–1806) of the Franks. Later, at the Atlantic Ocean, Portugal, Spain, the Netherlands, France, and the United Kingdom established their hegemonic centres.[11]

Political science

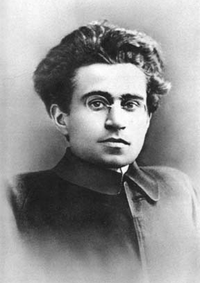

In the historical writing of the 19th century, the denotation of hegemony extended to describe the predominance of one country upon other countries; and, by extension, hegemonism denoted the Great Power politics (ca. 1880s–1914) for establishing hegemony (indirect imperial rule), that then leads to a definition of imperialism (direct foreign rule). In the early 20th century, in the field of international relations, the Italian Marxist philosopher Antonio Gramsci developed the theory of cultural domination (an analysis of economic class) to include social class; hence, the philosophic and sociologic theory of cultural hegemony analysed the social norms that established the social structures (social and economic classes) with which the ruling class establish and exert cultural dominance to impose their Weltanschauung (world view) — justifying the social, political, and economic status quo — as natural, inevitable, and beneficial to every social class, rather than as artificial social constructs beneficial solely to the ruling class.[12][13][14]

Antonio Gramsci was a communist Italian writer and politician who published influential works on hegemony during the height of Benito Mussolini’s power in Italy in the 1920’s and 1930’s. Gramsci is the theorist “most closely associated with the concept of hegemony,” and hegemony in politics was “somewhat limited until Antonio Gramsci’s intensive discussion of the concept in his political thought.” His most influential works on hegemony were written in his “Prison Notebooks” he wrote while imprisoned by Mussolini’s fascist regime from 1926 to 1934, shortly before his death. Gramsci defined hegemony as “a form of control exercised by a dominant class,” where the hegemonic class is the one “able to attain the consent of other social forces,” and the “retention of this consent is an ongoing project.” In terms of Gramsci’s adherence to Marxist and Leninist communism, this hegemonic class control is a function of economic production of the class. He focused on defining hegemony to both articulate the structures of bourgeois power in 19th and 20th century Europe and to “theorize…the necessary conditions for a successful overthrow of the bourgeoisie by the proletariat and its allies.”

Gramsci’s analysis was not limited to intra-class relations. He also defined hegemony in terms of the state, which later became relevant to scholars of international relations. Gramsci defines the state as “the entire complex of practical and theoretical activities” that the ruling class not only “justifies and maintains its dominance, but manages to win the active consent of those over whom it rules,” similar to how Athens willingly ceding its naval authority to Sparta in the Greek coalition against Xerxes’ invading Persian armies. The primary difference in this analogy is that Herodotus, Thucydides and the other Greek historians saw hegemony through the lens of alliances among states whereas Gramsci sees hegemony as the political interplay within coherent, defined social communities.

From the Gramsci analysis derived the political science denotation of hegemony as leadership; thus, the historical example of Prussia as the militarily and culturally predominant province of the German Empire (Second Reich 1871–1918); and the personal and intellectual predominance of Napoleon Bonaparte upon the French Consulate (1799–1804).[15] Contemporarily, in Hegemony and Socialist Strategy (1985), Ernesto Laclau and Chantal Mouffe defined hegemony as a political relationship of power wherein a sub-ordinate society (collectivity) perform social tasks that are culturally unnatural and not beneficial to them, but that are in exclusive benefit to the imperial interests of the hegemon, the superior, ordinate power; hegemony is a military, political, and economic relationship that occurs as an articulation within political discourse.[16]

Niccolo Machiavelli also heavily influenced Gramsci’s writings on hegemony within social classes. According to Gramsci, Machiavelli even “prepared the ground for Marxism by stressing ‘the conformity of means to ends’ in lower classes rising up against the bourgeois.” In Machiavelli’s magnum opus, The Prince, he draws an analogy to a centaur; half-animal, half-man where, “a prince must know how to use both natures, and that one without the other is not durable.” This represents the combination of “coercion and consent” that comprise hegemony, which Gramsci used in articulating tactics and strategy the lower classes could use to confront the bourgeois. Machiavelli also argues that people should determine common goals with each other to transform from an unorganized multitudine sciolta, or multitude of people, into a collective population with organized common goals, populo, using dialogue in a “public space.” Gramsci stipulates that people can become a hegemonic force in a “public space,” or forum to organize as a collective power and approach dealings with the ruling classes with much more leverage.

Sociology

Culturally, hegemony also is established by means of language, specifically the imposed lingua franca of the hegemon (leader state), which then is the official source of information for the people of the society of the sub-ordinate state. Therefore, in the selection of the particular information to be communicated to the sub-ordinate populace, the language of the hegemon thus limits what is communicated; hence, the source practises hegemonic influence upon the person or people receiving the given information. In contemporary society, the exemplar hegemonic organisations are churches and the mass communications media that continually transmit data and information to the public. As such, the ideologic content of the data and information are determined by the vocabulary with which the messages are presented — how the messages are presented; thereby determines the value of the information as "reliable" or "unreliable", as "true" or "false", for the recipient reader, listener, and viewer. Hence is language essential to the imposition, establishment, and functioning of the cultural hegemony that influences what and how people think about the status quo of their society. [citation needed]

See also

- 1954 Guatemalan coup d’état

- Imperialism, the Highest Stage of Capitalism (1916), by Lenin

- Balance of power

- Cultural hegemony

- Dominant ideology

- Hegemonic masculinity

- Hyperpower

- Monetary hegemony

- Post-hegemony

- Regional hegemony

- Soft power

- Chantal Mouffe

- Edward Soja

- David Harvey

- Noam Chomsky

References

- ^ a b Ross Hassig, Mexico and the Spanish Conquest (1994), pp. 23–24.

- ^ a b The Columbia Encyclopedia, Fifth Edition (1994) p. 1215.

- ^ Alan Bullock and Stephen Trombley, eds. The New Fontana Dictionary of Modern Thought, Third Edition (1999) pp. 387–388.

- ^ Clive Upton, William A. Kretzschmar, Rafal Konopka: Oxford Dictionary of Pronunciation for Current English. Oxford University Press (2001)

- ^ Oxford English Dictionary

- ^ US Hegemony

- ^ Henry Kissinger, Diplomacy (1984), pp. 137-138: "European coalitions were likely to arise to contain Germany's Nazis growing, potentially dominant, power"; p.145: "Unified Germany was achieving the strength to dominate Europe all by itself — an occurrence which Great Britain had always resisted in the past when it came about by conquest".

- ^ Christopher Hitchens Why Orwell Matters (2002) pp. 86–87.

- ^ George C. Kohn Dictionary of Wars (1986) p.496

- ^ Joseph S. Nye Sr., Understanding International Conflicts: An introduction to Theory and History, pp. 276-277

- ^ Henri Lefebvre, The Production of Space (1992)

- ^ Alan Bullock and Stephen Trombley, eds., The New Fontana Dictionary of Modern Thought, Third Edition (1999) pp. 387–388

- ^ K. J. Holsti, The Dividing Discipline: Hegemony and Diversity in International Theory (1985).

- ^ The Columbia Encyclopedia, Fifth Edition. (1994) p. 1215

- ^ Chris Cook, Dictionary of Historical Terms (1983) p. 142.

- ^ Ernest Laclau and Chantal Mouffe, Hegemony and Socialist Strategy, Second Edition. (2001) pp. 40-59, 125-144.

Further reading

- DuBois, T. D. (2005). "Hegemony, Imperialism and the Construction of Religion in East and Southeast Asia." History & Theory, 44, 4, 113-131.

- Hopper, P. (2007). Understanding Cultural Globalization. 1st ed. Malden, MA: Polity Press.

- Howson, Richard, ed. (2008). Hegemony: studies in consensus and coercion. Psychology Press. ISBN 978-0-415-95544-7.

- Joseph, Jonathan (2002). Hegemony: A Realist Analysis. Routledge. ISBN 0-415-26836-2.

- Slack, Jennifer Daryl (1996). "The Theory and Method of Articulation in Cultural Studies". Stuart Hall: Critical Dialogues in Cultural Studies. Routledge. pp. 112–127.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|editors=ignored (|editor=suggested) (help)