American Sign Language

| American Sign Language | |

|---|---|

| |

| Region | North America, West Africa, Central Africa |

Native speakers | 250,000–500,000 in the United States (1972)[1] |

| Dialects |

|

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-3 | ase |

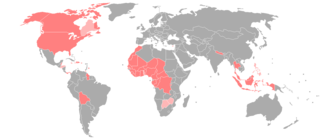

Areas where ASL or a dialect/derivative of ASL is the national sign language Areas where ASL is in significant use alongside another sign language | |

American Sign Language (ASL) is the predominant sign language of deaf communities in the United States and English-speaking parts of Canada. Besides North America, dialects of ASL and ASL-based creoles are used in many countries around the world, including much of West Africa and parts of Southeast Asia. ASL is most closely related to French Sign Language (FSL), and might be considered an FSL-based creole. Despite the fact that the United States, the United Kingdom, and Australia have English as a common oral language, ASL is not mutually intelligible with British Sign Language or with Auslan.

ASL originated in the early 19th century in the American School for the Deaf (ASD) in Hartford, Connecticut. Founded by Thomas Hopkins Gallaudet in 1817, the school adopted the pedagogical methods of the French Institut National de Jeunes Sourds de Paris, including the use of French Sign Language. The school brought together deaf students with their own home sign or village sign systems, and in this situation of language contact ASL was born. It has been proposed that this was an event of creole genesis, but ASL shows features atypical of creole languages, such as agglutinative morphology.

Despite its wide use, no accurate count of ASL users has been taken, though reliable estimates for American ASL users range from 250,000 to 500,000 persons. This includes a number of CODAs (children of deaf adults), who are more likely than deaf children to acquire ASL from birth. ASL users face stigma due to beliefs in the superiority of spoken language to signed language, compounded by the fact that ASL is often glossed in English due to the lack of a standard writing system. CODAs may be mistakenly labeled as "slow learners" rather than being recognized as bilinguals.

ASL signs have a number of phonemic components, including handshape, orientation, location, and movement. In addition, non-manual features can be phonemic, including movement of face and torso. Although iconicity does play a role in the language, ASL is not a form of pantomime, and there is evidence from language acquisition that iconic signs are processed similarly to non-iconic signs. ASL grammar is completely unrelated to that of English, although English loan words are often borrowed through fingerspelling. ASL has verbal agreement and aspectual marking, and has a productive system of forming agglutinative classifiers. It is disputed whether ASL is a subject-verb-object (SVO) or subject-object-verb (SOV) language.

Classification

ASL emerged as a language in the American School for the Deaf (ASD), founded in 1817.[2] This school brought together French Sign Language (FSL), various village sign languages, and home sign systems; ASL was created in this situation of language contact.[3][nb 1] Although signing had been used by Native Americans prior to the arrival of Europeans, it appears that these village sign languages were influenced instead by early British Sign Language.[4]

The influence of FSL on ASL is readily apparent; for example, it has been found that about 58% of signs in modern ASL are cognate to Old French Sign Language signs.[2][5] However, this is far less than the standard 80% measure used to determine whether related languages are actually dialects.[5] This suggests that nascent ASL was highly affected by the other signing systems brought by the ASD students, despite the fact that the school's original director Laurent Clerc taught in FSL.[2][5] In fact, Clerc reported that he often learned the students' signs rather than conveying FSL:[5]

I see, however, and I say it with regret, that any efforts that we have made or may still be making, to do better than, we have inadvertently fallen somewhat back of Abbé de l’Épée. Some of us have learned and still learn signs from uneducated pupils, instead of learning them from well instructed and experienced teachers.

— Clerc, 1852, from Woodward 1978:336

It has been proposed that ASL is a creole with FSL as the superstrate language and with the native village sign languages as substrate languages.[6] However, more recent research has shown that modern ASL does not share many of the structural features that characterize creole languages.[7] ASL may have begun as a creole and then undergone structural change over time, but it is also possible that it was never a creole-type language.[7] There are modality-specific reasons that sign languages tend towards agglutination, for example the ability to simultaneously convey information via the face, head, torso, and other body parts. This might override creole characteristics such as the tendency towards isolating morphology.[8] Additionally, Clerc and Gallaudet may have used an artificially constructed form of manually coded language in instruction rather than true FSL.[9]

There has been speculation that ASL may be distantly related to the British Sign Language family through Martha's Vineyard Sign Language (MVSL), known to have historical connections to Great Britain. But this has not been proven conclusively.[4]

Although the United States, the United Kingdom, and Australia share English as a common oral and written language, ASL is not mutually intelligible with British Sign Language (BSL) or Auslan.[4] All three languages show degrees of borrowing from English, but this alone is not sufficient for cross-language comprehension.[4] It has been found that a relatively high percentage (37–44%) of ASL signs have similar translations in Auslan, which for oral languages would suggest that they belong to the same language family.[10] However, this does not seem justified historically for ASL and Auslan, and it is likely that this resemblance is due to the higher degree of iconicity in signed languages in general, as well as contact with English.[11]

History

Prior to the birth of ASL, signed language had been used by various communities in the United States.[12] In the United States, as elsewhere in the world, hearing families with deaf children have historically employed ad-hoc home sign, which often reaches much higher levels of sophistication than gestures used by hearing people in spoken conversation.[12] As early as 1541 at first contact by Francisco Vásquez de Coronado, there were reports that the Plains Indians had developed a sign language to communicate between tribes of different languages.[13]

In the 19th century, a "triangle" of village sign languages was developed in New England: one in Martha's Vineyard, Massachusetts; one in Henniker, New Hampshire, and one in Sandy River Valley, Maine.[14] Martha's Vineyard Sign Language (MVSL), which was particularly important for the history of ASL, was used mainly in Chilmark, Massachusetts.[15] Due to inbreeding in the original community of English settlers of the 1690s, Chilmark had a high 4% rate of genetic deafness.[15] MVSL was used even by hearing residents whenever a deaf person was present.[15]

ASL is thought to have originated in the American School for the Deaf (ASD), founded in Hartford, Connecticut in 1817.[16] Originally known as The American Asylum, At Hartford, For The Education And Instruction Of The Deaf And Dumb, the school was founded by the Yale graduate and divinity student Thomas Hopkins Gallaudet.[17][18] Gallaudet, inspired by his success in demonstrating the learning abilities of a young deaf girl Alice Cogswell, traveled to Europe in order to learn deaf pedagogy from European institutions.[17] Ultimately, Gallaudet chose to adopt the methods of the French Institut National de Jeunes Sourds de Paris, and convinced Laurent Clerc, an assistant to the school's founder Charles-Michel de l'Épée, to accompany him back to the United States.[17][nb 2] Upon his return, Gallaudet founded the ASD on April 15, 1817.[17]

The largest group of students during the first seven decades of the school were from Martha’s Vineyard, and they brought MVSL with them.[19] There were also 44 students from around Henniker, New Hampshire, and 27 from a Sandy River, Maine, each of which had their own village sign language.[3][nb 3] Other students brought knowledge of their own home signs.[3] Laurent Clerc, the first teacher at ASD, taught using French Sign Language (FSL), which itself had developed in the Parisian school for the deaf established in 1755.[2] From this situation of language contact, a new language emerged, now known as ASL.[2] ASL was influenced by its forerunners but distinct from all of them.[2]

More schools for the deaf were founded after ASD, and knowledge of ASL spread to these schools.[2] In addition, the rise of deaf community organizations bolstered the continued use of ASL.[20] Societies such as the National Association of the Deaf and the National Fraternal Society of the Deaf held national conventions that attracted signers from across the country.[21] This all contributed to ASL's wide use over a large geographical area, atypical for a signed language.[5][22]

Up to the 1950s, the predominant method in deaf education was oralism – acquiring oral language comprehension and production.[23] Linguists did not consider signed language to be true "language," but rather something inferior.[23] Recognition of the legitimacy of ASL was achieved by William Stokoe, a linguist who arrived at Gallaudet University in 1955 when this was still the dominant assumption.[23] Aided by the civil rights movement of the 1960s, Stokoe argued for manualism, the use of sign language in deaf education.[23][24] Stokoe noted that signed language shares the important features that oral languages have as a means of communication, and even devised a writing system for ASL.[23] In doing so, Stokoe revolutionized both deaf education and linguistics.[23] In the 1960s, ASL was sometimes referred to as "Ameslan", but this term is now considered obsolete.[25]

Population

Counting the number of ASL speakers is difficult because ASL users have never been counted by the American census.[26][nb 4] The ultimate source for current estimates of the number of ASL users in the United States is a report for the National Census of the Deaf Population (NCDP) by Schein and Delk (1974).[27] Based on a 1972 survey of the NCDP, Schein and Delk provided estimates consistent with a signing population between 250,000 and 500,000.[1] The survey did not distinguish between ASL and other forms of signing; in fact, the name "ASL" was not yet in widespread use.[28]

Incorrect figures are sometimes cited for the population of ASL speakers in the United States based on misunderstandings of known statistics.[29] Demographics of the deaf population have been confused with those of ASL use, since adults who become deaf late in life rarely use ASL in the home.[30] This accounts for currently-cited estimations which are greater than 500,000; such mistaken estimations can reach as high as 15,000,000.[31] A 100,000-person lower bound has been cited for ASL users; the source of this figure is unclear, but it may be an estimate of prelingual deafness, which is correlated with but not equivalent to signing.[32]

ASL is sometimes incorrectly cited as the third- or fourth-most-spoken language in the United States.[33] These figures misquote Schein and Delk (1974), who actually concluded that ASL speakers constituted the third-largest population requiring an interpreter in court.[33] Although this would make ASL the third-most used language among monolinguals other than English, it does not imply that it is the fourth-most-spoken language in the United States, since speakers of other languages may also speak English.[34]

Geographic distribution

ASL is used throughout Anglo-America.[22] This contrasts with Europe, where a variety of sign languages are used within the same continent.[22] The unique situation of ASL seems to have been caused by the proliferation of ASL through schools influenced by the American School for the Deaf, wherein ASL originated, and the rise of community organizations for the deaf.[35]

Throughout West Africa, ASL-based sign languages are spoken by educated deaf adults.[36] These languages, imported by boarding schools, are often considered by associations to be the official sign languages of their countries, and are named accordingly, e.g. Nigerian Sign Language, Ghanaian Sign Language.[36] Such signing systems are found in Benin, Burkina Faso, Cote d'Ivoire, Ghana, Liberia, Mauritania, Mali, Nigeria, and Togo.[37] Due to lack of data, it is still an open question how similar these sign languages are to ASL.[38]

In addition to the aforementioned West African countries, ASL is reported to be used as a first language in Barbados, Bolivia, the Central African Republic, Chad, China (Hong Kong), the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Gabon, Jamaica, Kenya, Madagascar, the Philippines, Singapore, and Zimbabwe.[39]

Variation

Variation in ASL is found throughout the United States and Canada.[39]

Just as there are accents in speech, there are regional accents in sign. People from the South sign slower than people in the North — even people from northern and southern Indiana have different styles.

— Walker, Lou Ann (1987). A Loss for Words: The Story of Deafness in a Family. New York: HarperPerennial. p. 31. ISBN 0-06-091425-4.

Mutual intelligibility among these ASL varieties is high, and the variation is primarily lexical.[39] For example, there are three different words for English about in Canadian ASL; the standard way, and two regional variations (Atlantic and Ontario), as shown in the videos on the right.[40] Variation may also be phonological, meaning that the same sign may be signed in a different way depending on the region. For example, an extremely common type of variation is between the handshapes /1/, /L/, and /5/ in signs with one handshape.[41]

There is also a distinct variety of ASL used by the Black deaf community.[39] Black ASL evolved as a result of racially segregated schools in some states, which included the residential schools for the deaf.[42] Black ASL differs from standard ASL in vocabulary, phonology, and some grammatical structure.[39][42] While African American Vernacular English (AAVE) is generally viewed as more innovating than standard English, Black ASL is more conservative than standard ASL, preserving older forms of many signs.[42] Black sign language speakers use more two-handed signs than in white ASL, are less likely to show assimilatory lowering of signs produced on the forehead (e.g. KNOW), and use a wider signing space.[42] Modern Black ASL borrows a number of idioms from AAVE; for instance, the AAVE idiom "I feel you" is calqued into Black ASL.[43]

ASL is used internationally as a lingua franca, and a number of closely related sign languages derived from ASL are used in many different countries.[39] Even so, there have been varying degrees of divergence from standard ASL in these imported ASL varieties. Bolivian Sign Language is reported to be a dialect of ASL, no more divergent than other acknowledged dialects.[44] on the other hand, it is also known that some imported ASL varieties have diverged to the extent of being separate languages. For example, Malaysian Sign Language, which has ASL origins, is no longer mutually comprehensible with ASL and must be considered its own language.[45] For some imported ASL varieties, such as those used in West Africa, it is still an open question how similar they are to American ASL.[38]

When communicating with hearing English speakers, ASL-speakers often use what is commonly called Pidgin Signed English (PSE) or 'contact signing', a blend of English structure with ASL.[39][46] Various types of PSE exist, ranging from highly English-influenced PSE (practically relexified English), to PSE which is quite close to ASL lexically and grammatically, but may alter some subtle features of ASL grammar.[46] Fingerspelling may be used more often in PSE than it is normally used in ASL.[47] There have been some constructed sign languages, known as Manually Coded English (MCE), which match English grammar exactly and simply replace spoken words with signs; these systems are not considered to be varieties of ASL.[39][46]

Tactile ASL (TASL) is a variety of ASL used throughout the United States by and with the deaf-blind.[39] It is particularly common among those with Usher's syndrome, found especially in Louisiana and Seattle.[39] This syndrome results in deafness from birth followed by loss of vision later in life; consequently, those with Usher's syndrome often grow up in the deaf community using ASL, and later transition to TASL.[48] TASL differs from ASL in that signs are produced by touching the palms, and there are some grammatical differences from standard ASL in order to compensate for the lack of non-manual signing.[39]

Status

ASL is used as a lingua franca in deaf communities of several nations, though it is not universal.[39] Both the United States and Canada offer ASL interpreters in some legal and civic situations.[39]

ASL faces stigma due to beliefs that spoken language is superior to signed language, as well as the higher perceived status of English and the fact that ASL is sometimes written using English words.[49]

The majority of children born to deaf parents are hearing.[50] These children, known as CODAs ("Children Of Deaf Adults") in English and HEARING MOTHER^FATHER DEAF in ASL, are often more culturally deaf than deaf children, the majority of whom are born to hearing parents.[50] Unlike many deaf children, Codas acquire ASL as well as deaf cultural values and behaviors from birth.[50] These bilingual hearing children may be mistakenly labeled as being "slow learners" or as having "language difficulties" due to bias towards spoken language.[49]

Writing systems

There is no well-established writing system for ASL.[51]

The first systematic writing system for a sign language seems to be that of Roch-Ambroise Auguste Bébian, developed in 1825.[52] However, written sign language remained marginal among the public.[53]

In the 1960s linguist William Stokoe created Stokoe notation specifically for ASL. It is alphabetic, with a letter or diacritic for every phonemic (distinctive) hand shape, orientation, motion, and position, though it lacks any representation of facial expression, and is better suited for individual words than for extended passages of text.[54] Stokoe used this system for his 1965 A Dictionary of American Sign Language on Linguistic Principles.[55]

The first writing system to gain use among the public was SignWriting, proposed in 1974 by Valerie Sutton.[53] SignWriting consists of about 500 iconic graphs.[53] Currently it is in use in some schools for the deaf and among some adults.[53] SignWriting is not a phonemic orthography, and does not have a one-to-one map from phonological forms to written forms.[56]

The most widely used transcription system among academics is HamNoSys, developed at the University of Hamburg.[57] Based on Stokoe Notation, HamNoSys was expanded to about 200 graphs in order to allow transcription of any sign language.[57] Phonological features are usually indicated with single symbols, though the group of features that comprises a handshape is indicated collectively with a symbol.[57]

Several additional candidates for written ASL have appeared over the years, including Sign Script, ASL-phabet, and Si5s. ASL-phabet, for example, tolerates some ambiguity, and unlike SignWriting would only be understood by a fluent signer.

For English-speaking audiences, ASL is often glossed using English words. These glosses are typically all-capitalized and are arranged in ASL order. For example, the ASL sentence DOG NOW CHASE>IX=3 CAT, meaning "the dog is chasing the cat", uses NOW to mark ASL progressive aspect and shows ASL verbal inflection for the third person (written with >IX=3). However, glossing is not used to write the language for speakers of ASL.[51]

Phonology

[+ closed thumb][58]

[− closed thumb][58]

Each sign in ASL is composed of a number of distinctive components. A sign may use one hand or both. Each hand assumes a handshape with a particular orientation in a particular location on the body or in the "signing space", and may involve movement.[59] Changing any one of these may change the meaning of a sign, as illustrated by the ASL signs THINK and DISAPPOINTED:

|

|

There are also meaningful non-manual signals in ASL.[61] This may include movement of the eyebrows, the cheeks, the nose, the head, the torso, and the eyes.[61]

William Stokoe proposed that these components are analogous to the phonemes of spoken languages.[62][nb 5] There has also been a proposal that these are analogous to classes like place and manner of articulation.[62] As in spoken languages, these phonological units can be split into distinctive features.[58] For instance, the handshapes /2/ and /3/ are distinguished by the presence or absence of the feature [± closed thumb], as illustrated to the right.[58] ASL has processes of allophony and phonotactic restrictions.[63] There is ongoing research into whether ASL has an analog of syllables in spoken language.[64]

Grammar

ASL grammar is completely unrelated to that of English.[65] It lacks the inflections of English, such as tense and number, and does not use articles such as "the", but its spatial mode of expression has enabled it to develop an elaborate system of grammatical aspect that is absent from English.

Morphology

Iconicity

A common misconception is that signs are iconically self-explanatory, that they are a transparent imitation of what they mean, or even that they are pantomime.[66] In fact, many signs bear no resemblance to their referent, either because they were originally arbitrary symbols or because their iconicity has been obscured over time.[66] Even so, in ASL iconicity plays a significant role; a high percentage of signs resemble their referents in some way.[67] This is due to the fact that the medium of signed language — space — naturally allows more iconicity than oral language.[66]

In the era of the influential linguist Ferdinand de Saussure, it was assumed that the mapping between form and meaning in language must be completely arbitrary.[67] Although onomatopoeia is a clear exception, since words like 'choo-choo' bear clear resemblance to the sounds that they mimic, the Saussurean approach was to treat these as marginal exceptions.[68] ASL, with its significant inventory of iconic signs, directly challenges this theory.[69]

Research on acquisition of pronouns in ASL has shown that children do not always take advantage of the iconic properties of signs when interpreting their meaning. It has been found that when children acquire the pronoun ‘you’, the iconicity of the point (at the child) is often confused, being treated more like a name.[70] This is a similar finding to research in oral languages on pronoun acquisition. It has also been found that iconicity of signs does not affect immediate memory and recall; less iconic signs are remembered just as well as highly iconic signs.[71]

Derivation

Compounding is used to derive new words in ASL, which often differ in meaning from their constituent signs.[72] For example, the signs FACE and STRONG compound to create a new sign FACE^STRONG, meaning 'to resemble'.[72] Compounds undergo the phonetic process of "hold deletion", whereby the holds at the end of the first constituent and the beginning of the second are elided:[72]

| Individual signs | Compound sign | |

|---|---|---|

| FACE | STRONG | FACE^STRONG |

| MH | HMH | MMH |

Inflection

Verbs may be inflected for aspect.[74] Continuous aspect modifies how the movement of a sign is executed, incorporating rhythmic, circular movement.[75] Punctual aspect is achieved by modifying the sign so that it has a stationary hand position.[76]

ASL is also rich in verbal agreement.[76] This includes agreement with the subject, object, number, and reciprocity.[76] A certain class of verbs (e.g. GIVE) incorporate subject and object agreement by modifying where the sign begins and ends.[77] Number inflection is achieved by modifying the verb's path.[78] For instance, the sign ASK takes "exhaustive number" by using multiple, smaller iterations of the sign's movement; the resulting sign ASK[exhaustive] means "to ask each person a question".[78] Reciprocity is indicated by using two one-handed signs; for example, the sign SHOOT, made with a /L/ handshape with inward movement of the thumb, inflects to SHOOT[reciprocal], articulated by having two L-shaped hands "shooting" at each other.[78]

Classifiers

ASL has a productive system of classifiers that is part of its basic grammatical structure.[79] Each classifier morpheme consists of one phoneme.[79] Classifiers have two components: a "classifier handshape", and a "movement root" to which it is bound.[79] The classifier handshape represents the object as a whole, incorporating such attributes as surface, depth, and shape, and is usually very iconic.[80] The movement root may contain three morphemes: a path, to which is affixed a direction and a manner.[79] For example, a rabbit running downhill would use a classifier consisting of a bent V classifier handshape with a downhill-directed path.[79] If the rabbit is hopping, the path is executed with a bouncy manner.[79]

The frequency of classifier use depends greatly on genre, occurring at a rate of 17.7% in narratives but only 1.1% in casual speech and 0.9% in formal speech.[81]

Fingerspelling

ASL possesses a set of 26 handshapes, known as the American manual alphabet, which can be used to spell out words from the English language.[82] A common misconception is that ASL consists only of fingerspelling; although such a method (Manually Coded English) has been used, it is not ASL.[47]

Fingerspelling is a form of borrowing, a linguistic process wherein words from one language are incorporated into another.[47] In ASL, fingerspelling is used for proper nouns and for technical terms with no native ASL equivalent.[47] There are also some other loan words which are fingerspelled, either very short English words or abbreviations of longer English words, e.g. O-N from English 'on', and A-P-T from English 'apartment'.[47] Fingerspelling may also be used to emphasize a word that would normally be signed otherwise.[47]

Syntax

It is disputed whether ASL word order is Subject–Object–Verb (SOV) or Subject–Verb–Object (SVO). SOV order facilitates the use directional space for grammatical purposes. Due to the emphasis on English in most educational environments, ASL is now often altered to a more English like SVO order (which is fast becoming the assumed word order, however, despite the utterances being marked either with non-manual signals like eyebrow or body position, or with prosodic marking such as pausing, it is impossible to effectively use directional verbs if the verb appears before the object (which must then be moved through space, in or to its targeted direction)

Non-manual grammatical marking (such as eyebrow movement or head-shaking may optionally spread over the c-command domain of the node which it is attached to).[83]

Topicalization

ASL exhibits a phenomenon known as topicalization, the movement of a constituent to the beginning of the sentence.[84] This produces several different word orders, including SOV and VOS. While different word orders place emphasis on different topics, they are all considered grammatically acceptable.[85]

In non-topicalized SVO sentences, all constituents are signed contiguously, without any pauses.[86]

FATHER – LOVE – CHILD

"The father loves the child."[87]

In OSV sentences, the object is topicalized, marked by a forward head-tilt and a pause.[88]

CHILDtopic, FATHER – LOVE

"The father loves the child."[89]

Subject Copy and Null Subject

Even more word orders can be obtained through the phenomena of subject copy and null subject. In subject copy, the subject is repeated at the end of the sentence, accompanied by head nodding, either for clarification or emphasis.[90]

FATHER – LOVE – CHILD – FATHERcopy

"The father loves the child."[91]

Subjects can be copied even in a null subject sentence, in which the subject is omitted from its original position, yielding a VOS construction.[92]

LOVE – CHILD – FATHERcopy

"The father loves the child."[93]

Topicalization, accompanied with a null subject and a subject copy, can produce yet another word order, OVS.

CHILDtopic, LOVE – FATHERcopy

"The father loves the child."[94]

These properties of ASL allow it a variety of word orders, leading many to question which is the true, underlying, “basic” order.

Alternative Word Order Hypotheses

While most linguists agree on a basic word order of SVO and acknowledge the phenomena listed above,[95] there are several other proposals that attempt to account for the flexibility of word order in ASL. It has been said that discourse-oriented languages like ASL are best described with a topic-comment structure.[96] In such a structure, substituents are ordered not by their syntactic properties, but by their importance in the sentence. This provides an ASL sentence with versatility, allowing the topic of the sentence to be easily identified and, when appropriate, emphasized. Another hypothesis is that ASL exhibits free word order, in which syntax is not encoded in word order whatsoever, but can be encoded by other means (i.e. head nods, eyebrow movement, body position).[97]

See also

- American Sign Language literature

- Bimodal bilingualism

- Sign name

- Legal recognition of sign languages

Notes

- ^ In particular, Martha's Vineyard Sign Language, Henniker Sign Language, and Sandy River Valley Sign Language were brought to the school by students. See Padden (2010:11) and Lane, Pillard & French (2000:17).

- ^ The Abbé Charles-Michel de l'Épée, founder of the Parisian school Institut National de Jeunes Sourds de Paris, was the first to acknowledge that sign language could be used to educate the deaf. An oft-repeated folk tale states that while visiting a parishioner, Épee met two deaf daughters conversing with each other using FSL. The mother explained that her daughters were being educated privately by means of pictures. Épée is said to have been inspired by these deaf children when he established the first educational institution for the deaf. See:

- Ruben, Robert J. (2005). "Sign language: Its history and contribution to the understanding of the biological nature of language". Acta Oto-laryngologica. 125 (5): 464–7. doi:10.1080/00016480510026287. PMID 16092534.

- Padden, Carol A. (2001). Folk Explanation in Language Survival in: Deaf World: A Historical Reader and Primary Sourcebook, Lois Bragg, Ed. New York: New York University Press. pp. 107–108. ISBN 0-8147-9853-5.

- ^ Whereas deafness was genetically recessive on Martha's Vineyard, it was dominant in Henniker. On the one hand, this dominance likely aided the development of sign language in Henniker since families would be more likely to have the critical mass of deaf people necessary for the propagation of signing. On the other hand, in Martha's Vineyard the deaf were more likely to have more hearing relatives, which may have fostered a sense of shared identity that lead to more inter-group communication than in Henniker. See Lane, Pillard & French (2000:39).

- ^ Although some surveys of smaller scope measure ASL use, such as the California Department of Education recording ASL use in the home when children begin school, ASL use in the general American population has not been directly measured. See Mitchell et al. (2006:1).

- ^ Stokoe himself termed these cheremes, but other linguists have referred to them as phonemes. See Bahan (1996:11).

References

- ^ a b Mitchell et al. (2006:26)

- ^ a b c d e f g Bahan (1996:7)

- ^ a b c Padden (2010:11)

- ^ a b c d Johnson & Schembri (2007:68)

- ^ a b c d e Padden (2010:14)

- ^ Kegl (2008:493)

- ^ a b Kegl (2008:501)

- ^ Kegl (2008:502)

- ^ Kegl (2008:497)

- ^ Johnson & Schembri (2007:69)

- ^ Johnson & Schembri (2007:70)

- ^ a b Bahan (1996:5)

- ^ Ceil Lucas, 1995, The Sociolinguistics of the Deaf Community p. 80.

- ^ Lane, Pillard & French (2000:17)

- ^ a b c Bahan (1996:5–6)

- ^ Bahan (1996:4)

- ^ a b c d "A Brief History of ASD". American School for the Deaf. n.d. Retrieved November 25, 2012.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: year (link) - ^ "A Brief History Of The American Asylum, At Hartford, For The Education And Instruction Of The Deaf And Dumb". 1893. Retrieved November 25, 2012.

- ^ Padden (2010:10)

- ^ Bahan (1996:8)

- ^ Padden (2010:13)

- ^ a b c Padden (2010:12)

- ^ a b c d e f Armstrong & Karchmer (2002)

- ^ Stokoe, William C. 1960. Sign Language Structure: An Outline of the Visual Communication Systems of the American Deaf, Studies in linguistics: Occasional papers (No. 8). Buffalo: Dept. of Anthropology and Linguistics, University of Buffalo.

- ^ "American Sign Language, ASL or Ameslan". Handspeak.com. Retrieved 2012-05-21.

- ^ Mitchell et al. (2006:1)

- ^ Mitchell et al. (2006:17)

- ^ Mitchell et al. (2006:18)

- ^ Mitchell et al. (2006:20)

- ^ Mitchell et al. (2006:21)

- ^ Mitchell et al. (2006:1, 21)

- ^ Mitchell et al. (2006:22)

- ^ a b Mitchell et al. (2006:15, 22)

- ^ Mitchell et al. (2006:21–22)

- ^ Padden (2010:12–14)

- ^ a b Nyst (2010:410)

- ^ Nyst (2010:406)

- ^ a b Nyst (2010:411)

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m "American Sign Language". SIL International. n.d. Retrieved December 3, 2012.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ a b c d Bailey & Dolby (2002:1–2)

- ^ Lucas et al.

- ^ a b c d Solomon (2010:4)

- ^ Solomon (2010:10)

- ^ "Bolivian Sign Language". SIL International. n.d. Retrieved December 3, 2012.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Hurlbut (2003, 7. Conclusion)

- ^ a b c Nakamura, Karen (2008). "About ASL". Deaf Resource Library. Retrieved December 3, 2012.

- ^ a b c d e f Costello (2008:xxv)

- ^ Collins (2004:33)

- ^ a b Bishop & Hicks (2005:195)

- ^ a b c Bishop & Hicks (2005:192)

- ^ a b Supalla & Cripps (2011, ASL Gloss as an Intermediary Writing System)

- ^ van der Hulst & Channon (2010:153)

- ^ a b c d van der Hulst & Channon (2010:154)

- ^ Armstrong, David F., and Michael A. Karchmer. "William C. Stokoe and the Study of Signed Languages." Sign Language Studies 9.4 (2009): 389-397. Academic Search Premier. Web. 7 June 2012.

- ^ Stokoe, William C.; Dorothy C. Casterline; Carl G. Croneberg. 1965. A dictionary of American sign languages on linguistic principles. Washington, D.C.: Gallaudet College Press

- ^ van der Hulst & Channon (2010:163)

- ^ a b c van der Hulst & Channon (2010:155)

- ^ a b c d Bahan (1996:12)

- ^ a b Bahan (1996:10)

- ^ Bahan (1996:11)

- ^ a b Bahan (1996:49)

- ^ a b van der Hulst & Channon (2010, p.601, note 15)

- ^ Bahan (1996:12, 9)

- ^ Bahan (1995:15)

- ^ Bishop & Hicks (2005:188)

- ^ a b c Costello (2008:xxiii)

- ^ a b Liddell (2002:60)

- ^ Liddell (2002:61)

- ^ Liddell (2002:62)

- ^ Petitto, Laura A. (1987). "On the autonomy of language and gesture: Evidence from the acquisition of personal pronouns in American sign language". Cognition. 27 (1): 1–52. doi:10.1016/0010-0277(87)90034-5. PMID 3691016.

- ^ Klima & Bellugi (1979:27)

- ^ a b c Bahan (1996:20)

- ^ Bahan (1996:21)

- ^ Bahan (1996:27)

- ^ Bahan (1996:27–28)

- ^ a b c Bahan (1996:28)

- ^ Bahan (1996:28–29)

- ^ a b c Bahan (1996:29)

- ^ a b c d e f Bahan (1996:26)

- ^ Valli & Lucas (2000:86)

- ^ Morford, Jill; MacFarlane, James (2003). "Frequency Characteristics of American Sign Language". Sign Language Studies. 3 (2): 213. doi:10.1353/sls.2003.0003.

- ^ Costello (2008:xxiv)

- ^ Bahan (1996:31)

- ^ Valli, Clayton (2005). Linguistics of American Sign Language: An Introduction. Washington, D.C.: Clerc Books. p. 85. ISBN 1-56368-283-4.

- ^ Liddel, Scott K. (1980). American Sign Language Syntax. The Hague, The Netherlands: Mouton Publishers. p. 59. ISBN 90-279-3437-1.

- ^ Valli, Clayton (2005). Linguistics of American Sign Language: An Introduction. Washington, D.C.: Clerc Books. p. 84. ISBN 1-56368-283-4.

- ^ Valli, Clayton (2005). Linguistics of American Sign Language: An Introduction. Washington, D.C.: Clerc Books. p. 84. ISBN 1-56368-283-4.

- ^ Valli, Clayton (2005). Linguistics of American Sign Language: An Introduction. Washington, D.C.: Clerc Books. p. 86. ISBN 1-56368-283-4.

- ^ Valli, Clayton (2005). Linguistics of American Sign Language: An Introduction. Washington, D.C.: Clerc Books. p. 86. ISBN 1-56368-283-4.

- ^ Valli, Clayton (2005). Linguistics of American Sign Language: An Introduction. Washington, D.C.: Clerc Books. p. 84. ISBN 1-56368-283-4.

- ^ Valli, Clayton (2005). Linguistics of American Sign Language: An Introduction. Washington, D.C.: Clerc Books. p. 84. ISBN 1-56368-283-4.

- ^ Valli, Clayton (2005). Linguistics of American Sign Language: An Introduction. Washington, D.C.: Clerc Books. p. 86. ISBN 1-56368-283-4.

- ^ Valli, Clayton (2005). Linguistics of American Sign Language: An Introduction. Washington, D.C.: Clerc Books. p. 86. ISBN 1-56368-283-4.

- ^ Valli, Clayton (2005). Linguistics of American Sign Language: An Introduction. Washington, D.C.: Clerc Books. p. 86. ISBN 1-56368-283-4.

- ^ Neidle, Carol (2000). The Syntax of American Sign Language: Functional Categories and Hierarchical Structures. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press. p. 59. ISBN 0-262-14067-5.

- ^ Lillo-Martin, Diane (1986). "Two Kinds of Null Arguments in American Sign Language" (PDF). Natural Language and Linguistic Theory. 4 (4): 415. Retrieved 20 April 2013.

{{cite journal}}: More than one of|pages=and|page=specified (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Neidle, Carol (2000). The Syntax of American Sign Language: Functional Categories and Hierarchical Structures. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press. p. 59. ISBN 0-262-14067-5.

Bibliography

- Armstrong, David; Karchmer, Michael (2002), "William C. Stokoe and the Study of Signed Languages", in Armstrong, David; Karchmer, Michael; Van Cleve, John (eds.), The Study of Signed Languages, Gallaudet University, pp. xi–xix, ISBN 978-1-56368-123-3, retrieved November 25, 2012

{{citation}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Bahan, Benjamin (1996). Non-Manual Realization of Agreement in American Sign Language (PDF). Boston University. Retrieved November 25, 2012.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Bailey, Carol; Dolby, Kathy (2002). The Canadian dictionary of ASL. Edmonton, AB: The University of Alberta Press. ISBN 0888643004.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Bishop, Michele; Hicks, Sherry (2005). "Orange Eyes: Bimodal Bilingualism in Hearing Adults from Deaf Families" (PDF). Sign Language Studies. 5 (2). Gallaudet University Press: 188–230. doi:10.1353/sls.2005.0001. Retrieved December 3, 2012.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Collins, Steven (2004). Adverbial Morphemes in Tactile American Sign Language. Union Institute & University.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Costello, Elaine (2008). American Sign Language Dictionary. Random House. ISBN 0375426167. Retrieved November 26, 2012.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Hurlbut, Hope (2003), "A Preliminary Survey of the Signed Languages of Malaysia", in Baker, Anne; van den Bogaerde, Beppie; Crasborn, Onno (eds.), Cross-linguistic perspectives in sign language research: selected papers from TISLR (PDF), Hamburg: Signum Verlag, pp. 31–46, retrieved December 3, 2012

{{citation}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Johnson, Trevor; Schembri, Adam (2007). Australian Sign Language (Auslan): An introduction to sign language linguistics. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521540569. Retrieved November 27, 2012.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Kegl, Judy (2008). "The Case of Signed Languages in the Context of Pidgin and Creole Studies". In Kouwenberg, Silvia; Singler, John (eds.). The Handbook of Pidgin and Creole Studies. Blackwell Publishing. ISBN 0521540569. Retrieved November 27, 2012.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Klima, Edward S.; Bellugi, Ursula (1979). The signs of language. Boston: Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-80796-9.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Lane, Harlan; Pillard, Richard; French, Mary (2000). "Origins of the American Deaf-World" (PDF). Sign Language Studies. 1 (1). Gallaudet University Press: 17–44. doi:10.1353/sls.2000.0003. Retrieved November 25, 2012.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Liddell, Scott (2002), "Modality Effects and Conflicting Agendas", in Armstrong, David; Karchmer, Michael; Van Cleve, John (eds.), The Study of Signed Languages, Gallaudet University, pp. xi–xix, ISBN 978-1-56368-123-3, retrieved November 26, 2012

{{citation}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Lucas, Ceil; Bayley, Robert; Valli, Clayton (2003). What’s your sign for pizza?: An introduction to variation in American Sign Language. Washington, DC: Gallaudet University Press. ISBN 1563681447.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Mitchell, Ross; Young, Travas; Bachleda, Bellamie; Karchmer, Michael (2006). "How Many People Use ASL in the United States?: Why Estimates Need Updating" (PDF). Sign Language Studies. 6 (3). Gallaudet University Press. ISSN 0302-1475. Retrieved November 27, 2012.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Nyst, Victoria (2010), "Sign languages in West Africa", in Brentari, Diane (ed.), Sign Languages, Cambridge University Press, pp. 405–432, ISBN 978-0-521-88370-2

{{citation}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Padden, Carol (2010), "Sign Language Geography", in Mathur, Gaurav; Napoli, Donna (eds.), Deaf Around the World (PDF), New York: Oxford University Press, pp. 19–37, ISBN 0199732531, retrieved November 25, 2012

{{citation}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Solomon, Andrea (2010). Cultural and Sociolinguistic Features of the Black Deaf Community (Honors Thesis). Carnegie Mellon University. Retrieved December 4, 2012.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Supalla, Samuel; Cripps, Jody (2011). "Toward Universal Design in Reading Instruction" (PDF). Bilingual Basics. 12 (2). Retrieved January 5, 2012.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Valli, Clayton; Lucas, Ceil (2000). Linguistics of American Sign Language. Gallaudet University Press. ISBN 1-56368-097-1. Retrieved December 2, 2012.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - van der Hulst, Harry; Channon, Rachel (2010), "Notation systems", in Brentari, Diane (ed.), Sign Languages, Cambridge University Press, pp. 151–172, ISBN 978-0-521-88370-2

{{citation}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)