Black Hawk Down (film)

| Black Hawk Down | |

|---|---|

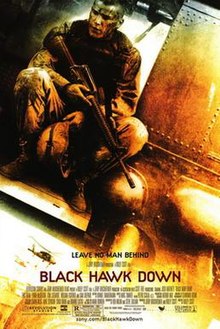

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Ridley Scott |

| Screenplay by | Ken Nolan |

| Produced by | Jerry Bruckheimer Ridley Scott |

| Starring | Josh Hartnett Eric Bana Ewan McGregor Tom Sizemore William Fichtner Sam Shepard |

| Cinematography | Sławomir Idziak |

| Edited by | Pietro Scalia |

| Music by | Hans Zimmer |

Production companies | |

| Distributed by | Columbia Pictures |

Release dates |

|

Running time | 144 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $92 million |

| Box office | $172,989,651[1] |

Black Hawk Down is a 2001 American war film directed by Ridley Scott. It is an adaptation of the 1999 book of the same name by Mark Bowden, which chronicles the events of the Battle of Mogadishu, a raid integral to the United States' effort to capture Somali warlord Mohamed Farrah Aidid.

The film features a large ensemble cast, including Josh Hartnett, Eric Bana, Ewan McGregor, Tom Sizemore, William Fichtner and Sam Shepard. The film won two Oscars for Best Film Editing and Best Sound at the 74th Academy Awards.[2] The film was received positively by American film critics, but was strongly criticized by Somalis.[3]

Plot

In 1993, famine and civil war have gripped Somalia, resulting in over 300,000 civilian deaths and a major United Nations peacekeeping operation. With the bulk of the peacekeepers withdrawn, the Somali militia loyal to the warlord Mohamed Farrah Aidid have declared war on the remaining U.N. personnel. In response, U.S. Army Rangers, Delta Force soldiers, and 160th SOAR aviators are deployed to Somalia to capture Aidid, who has proclaimed himself president of the country.

To cement his power and subdue the population of Somalia, Aidid and his militia seize Red Cross food shipments, coercing the cooperation of the people, while the U.N. forces are powerless to directly intervene. Outside Mogadishu, Rangers and Delta Force operators capture Osman Ali Atto, a warlord selling arms to Aidid's militia. Shortly thereafter, a mission is planned to capture Omar Salad Elmi and Abdi Hassan Awale Qeybdiid, two of Aidid's top advisers.

The U.S. forces include experienced men as well as new recruits, including Private First Class Todd Blackburn and a desk clerk going on his first mission. When his Lieutenant is removed from duty after having an epileptic seizure, Staff Sergeant Matthew Eversmann is placed in command of Ranger Chalk Four, his first command.

The operation is launched and Delta Force operators successfully capture Aidid's advisers inside the target building. The Rangers and helicopters escorting the ground-extraction convoy take heavy fire, while SGT Eversmann's Chalk Four is dropped a block away by mistake. Blackburn is severely injured after falling from one of the Black Hawk helicopters, so three Humvees led by Sergeant Jeff Struecker are detached from the convoy to return Blackburn to the U.N.-held Mogadishu Airport.

SGT Dominick Pilla is shot and killed just as Struecker's column gets underway, and shortly thereafter Black Hawk Super-Six One, piloted by CWO Clifton "Elvis" Wolcott, is shot down by a rocket-propelled grenade (RPG) and crashes deep within the city. Both pilots are killed, the two crew chiefs are wounded, and one Delta Force sniper on board escapes in another helo that makes it back to base.

The ground forces are rerouted to converge on the crash site. The Somali militia throws up roadblocks, causing LTC Danny McKnight's Humvee column to lose its way, while sustaining heavy casualties. Meanwhile, two Ranger Chalks, including Eversmann's unit, reach Super-Six One's crash site and set up a defensive perimeter to await evacuation with the two wounded men and the fallen pilots. In the interim, Super-Six Four, piloted by CWO Michael Durant, is also shot down by an RPG and crashes several blocks away.

With CPT Mike Steele's Rangers pinned down and sustaining heavy casualties, no ground forces can reach Super Six Four's crash site nor reinforce the Rangers defending Super Six One. Two Delta Force snipers, SFC Randy Shughart and MSG Gary Gordon are inserted by helicopter to Super Six Four's crash site, where they find Durant still alive. The crash site is eventually overrun, Gordon and Shughart are killed, and Durant is captured and taken to Aidid.

McKnight's column gives up the attempt to reach Six-One's crash site and returns to base with their prisoners and the casualties. The men prepare to go back to extract the pinned down Rangers and the fallen pilots and MG Garrison sends LTC Joe Cribbs to ask for reinforcements from the 10th Mountain Division, including Malaysian and armored Pakistani forces, to mobilize as a relief column.

As night falls the Somali militia launch a sustained assault on the trapped Americans at Super Six One's crash site. The militia is held off throughout the night by strafing runs and rocket attacks from AH-6J Little Bird helicopter gunships of the Nightstalkers, until the 10th Mountain Division's relief column is able to reach the site. The wounded and casualties are evacuated in the vehicles, but a handful of remaining Rangers and Delta Force soldiers are forced to run from the crash site back to the stadium, in the UN Safe Zone.

The closing credits detail the results of the raid: 19 American soldiers were killed, with over 1,000 Somalis dead. Durant was released after 11 days of captivity. Delta Force snipers Gordon and Shughart were the first soldiers to be posthumously awarded the Medal of Honor since the Vietnam War. On August 2, 1996, Aidid was killed in a battle with a rival clan. General Garrison retired the following day.

Cast

75th Rangers

- Sam Shepard as MG William F. Garrison, commander of Task Force Ranger

- Josh Hartnett as SSG Matt Eversmann, the leader of Chalk 4

- Ewan McGregor as SPC John "Grimesey" Grimes, a desk clerk

- Tom Sizemore as LTC Danny McKnight, the commander of the 3rd Ranger Battalion

- Ewen Bremner as SPC Shawn Nelson, a squad gunner

- Gabriel Casseus as SPC Mike Kurth

- Hugh Dancy as SFC Kurt "Doc" Schmid, a medic of Chalk 4 (portrayed as a Ranger in the film; was Delta Force in real life)

- Ioan Gruffudd as LT John Beales

- Tom Guiry as SSG Ed Yurek

- Charlie Hofheimer as CPL Jamie Smith

- Danny Hoch as SPC Dominick Pilla

- Jason Isaacs as CPT Mike Steele, commander, Bravo Company, 3rd Ranger Battalion

- Brendan Sexton III as PVT Richard "Alphabet" Kowalewski

- Brian Van Holt as SSG Jeff Struecker

- Ian Virgo as PVT John Waddell

- Tom Hardy as SPC Lance Twombly

- Gregory Sporleder as SGT Scott Galentine, the ground radio and telephone communications operator of Chalk 4

- Carmine Giovinazzo as SGT Mike Goodale

- Chris Beetem as SGT Casey Joyce

- Matthew Marsden as SPC Dale Sizemore

- Orlando Bloom as PFC Todd Blackburn

- Enrique Murciano as SGT Lorenzo Ruiz

- Michael Roof as PVT John Maddox

Delta Force

- Eric Bana as SFC Norm "Hoot" Gibson (based on SFC John Macejunas, SFC Norm Hooten and SFC Matthew Rierson)

- William Fichtner as SFC Jeff Sanderson (based on SFC Paul Howe)[4]

- Kim Coates as MSG Tim "Griz" Martin

- Steven Ford as LTC Joe Cribbs

- Željko Ivanek as LTC Gary Harrell, the commander of C Squadron

- Johnny Strong as SFC Randy Shughart, a sniper flying on Black Hawk Super Six-Two

- Nikolaj Coster-Waldau as MSG Gary Gordon, a sniper flying on Black Hawk Super Six-Two

- Richard Tyson as SSG Daniel Busch, a sniper flying on Black Hawk Super Six-One

160th SOAR – Night Stalkers

- Ron Eldard as CW4 Michael Durant, pilot of Super Six-Four

- Glenn Morshower as LTC Tom Matthews, the commander of 1st Battalion

- Jeremy Piven as CWO Clifton Wolcott, the pilot of Super Six-One, the first Black Hawk down

- Boyd Kestner as CW3 Mike Goffena, pilot of Super Six-Two who inserts Gordon and Shughart

Miscellaneous

- George Harris as Osman Atto

- Razaaq Adoti as Yousuf Dahir Mo'alim, the Somali militia leader

- Treva Etienne as Firimbi, Somali war chief and Michael Durant's captor

- Ty Burrell as United States Air Force Pararescue Timothy A. Wilkinson.

Background and production

Black Hawk Down was originally the idea of director Simon West, who suggested to Jerry Bruckheimer that he should buy the film rights to the book Black Hawk Down: a Story of Modern War by Mark Bowden and let him (West) direct; but West moved on to direct Lara Croft: Tomb Raider (2001) instead.[5]

Despite Ken Nolan's being credited as screenwriter, others contributed uncredited: Mark Bowden wrote an adaptation of his own book, Steven Gaghan was hired to do a rewrite, Steven Zaillian rewrote the majority of the Gaghan and Nolan's work, Sam Shepard (MGen. Garrison) wrote some of his dialogue, and Eric Roth wrote Josh Hartnett and Eric Bana's concluding speeches. Ken Nolan was on set for four months rewriting his own script and the previous work by Gaghan, Zaillian, and Bowden, and was finally given sole screenwriting credit by a WGA committee.

Filming began in March 2001 in Kenitra, Morocco, and concluded in late June.[6]

Composed mostly of participant accounts, SPC John Stebbins became the fictional "John Grimes", because Stebbins was convicted by court martial, in 1999, for sexually assaulting his daughter.[7] Reporter Bowden said the Pentagon requested the change.[8] Bowden wrote early screenplay drafts, before Bruckheimer gave it to screenwriter Nolan. The POW-captor conversation, between pilot Mike Durant and militiaman Firimbi, is from a Bowden script draft.

For military verisimilitude, the Ranger actors took a crash, one-week Ranger familiarization course at Fort Benning, the Delta Force actors took a two-week commando course from the 1st Special Warfare Training Group at Fort Bragg and Ron Eldard and the actors playing 160th SOAR helicopter pilots were lectured by captured aviator Michael Durant at Fort Campbell. The U.S. Army supplied the matériel and the helicopters from the 160th Special Operations Aviation Regiment; most pilots (e.g., Keith Jones, who speaks some dialogue) participated in the battle on October 3–4, 1993.[9]

On the last day of their week-long Army Ranger orientation at Fort Benning, the actors who portrayed the Rangers received a letter which had been anonymously slipped under their door. The letter thanked them for all their hard work, and asked them to "tell our story true", signed with the names of the men who died in the Mogadishu firefight.[9] Moreover, a platoon of Rangers from B-3/75 did the fast-roping scenes and were extras; John Collette, a Ranger Specialist during the actual battle served as a stunt performer.[10] Many of the actors bonded with the soldiers who trained them for their roles. Actor Tom Sizemore said,"What really got me at training camp was the Ranger Creed. I don't think most of us can understand that kind of mutual devotion. It's like having 200 best friends and every single one of them would die for you".[9]

Although the filmmakers originally considered filming in Jordan, they found the city of Amman too built up and landlocked. Scott and production designer Arthur Max turned instead to Morocco, where they had previously worked on Gladiator. Scott preferred the urban look for authenticity.[9] Most of the film was photographed in the cities of Rabat and Salé in Morocco; the Task Force Ranger base sequences were filmed at Kénitra.[11]

In order to keep the film at a manageable length, 100 key characters in the book were condensed to 39. The movie also features no Somali actors.[12] Additionally, no Somali consultants were hired for accuracy according to writer Bowden.[13]

The film features soldiers wearing helmets with their last names on them. Although this was an inaccuracy, Ridley Scott felt it was necessary to help the audience distinguish among the characters because "they all look the same once the uniforms are on".[14]

Release

Box office performance

Black Hawk Down had a limited release in four theaters on December 28, 2001, in order to be eligible for the 2001 Oscars. It earned $179,823 in its first weekend, averaging $44,956 per theater. On January 11, 2002, the release expanded to 16 theaters and continued to do well with a weekly gross of $1,118,003 and an average daily per theater gross of $9,982 18, 2002, the film had its wide release, opening at 3,101 theaters and earning $28,611,736 in its first wide release weekend to finish first at the box office for the weekend. Opening on the Martin Luther King holiday, the film grossed $5,014,475 on the holiday of Monday, January 21, 2002, for a 4-day weekend total of $33,628,211. Only Titanic had previously grossed more money over the Martin Luther King holiday weekend. Black Hawk Down went on to finish first at the box office during its first three weeks of wide release. When the film was pulled from theatres on April 14, 2002, after its 15th week, it had grossed $108,638,746 domestically and $64,350,906 overseas for a worldwide total of $172,989,651.[1]

Critical response

The film received many positive reviews from mainstream critics. Empire magazine gave it a verdict of "ambitious, sumptuously framed, and frenetic, Black Hawk Down is nonetheless a rare find of a war movie which dares to turn genre convention on its head".[15] Film Critic Mike Clark of USA Today wrote that the film "extols the sheer professionalism of America's elite Delta Force – even in the unforeseen disaster that was 1993's Battle of Mogadishu." and praised Scott's direction "in relating the conflict, in which 18 Americans died and 70-plus were injured, the standard getting-to-know-you war-film characterizations are downplayed. While some may regard this as a shortcoming, it is, in fact, a virtue".[16] It has a 76% "Fresh" rating on Rotten Tomatoes,[17] and a rating of 74 on Metacritic.[18]

The film has had a small cultural legacy which has been studied academically by media analysts dissecting how media reflects American perceptions of war. Newsweek writer Evan Thomas considered the movie one of the most culturally significant films of the George W. Bush presidency, writing that the film "may have been antiwar on the surface, but I believe it was fundamentally prowar. Though it depicted a shameful defeat, the soldiers were heroes willing to die for their brothers in arms. The movie showed brutal scenes of killing, but also courage, stoicism and honor. The overall effect was stirring, if slightly pornographic, and it seemed to enhance the desire of Americans for a thumping war to avenge 9/11."[19]

Another article by Stephen A. Klien written for Critical Studies in Media Communication argued that the film's emphasis on "a hyperreal spectacle of war that both encourages audiences to empathize with the dominant 'pro-soldier' message" would lead audiences to "conflate personal support of American soldiers with support of American military policy" and discourage "critical public discourse concerning justification for and execution of military interventions policy."[20]

Soundtrack

Accolades

| Award | Category | Nominee | Result |

|---|---|---|---|

| NBR Award | Top Ten Films | Won | |

| AFI Award | Cinematographer of the Year | Slawomir Idziak | Nominated |

| Director of the Year | Ridley Scott | Nominated | |

| Editor of the Year | Pietro Scalia | Nominated | |

| Movie of the Year | Jerry Bruckheimer Ridley Scott |

Nominated | |

| Production Designer of the Year | Arthur Max | Nominated | |

| Academy Award | Best Film Editing | Pietro Scalia | Won |

| Best Sound | Michael Minkler Myron Nettinga Chris Munro |

Won | |

| Best Cinematography | Salwomir Idziak | Nominated | |

| Best Director | Ridley Scott | Nominated | |

| Saturn Award | Best Action/Adventure/Thriller Film | Nominated | |

| Eddie Award | Best Edited Feature Film - Dramatic | Pietro Scalia | Won |

| ADG Excellence in Production Design Award | Contemporary Film | Keith Pain Marco Trentini Gianni Giovagnoni Cliff Robinson Pier Luigi Basile Ivo Husnjak Arthur Max |

Nominated |

| Harry Award | Won | ||

| BAFTA Award | Best Cinematography | Salwomir Idziak | Nominated |

| Best Editing | Pietro Scalia | Nominated | |

| Best Sound | Chris Munro Per Hallberg Michael Minkler Myron Nettinga Karen Baker Landers |

Nominated | |

| Golden Reel Award | Best Sound Editing - Dialogue and ADR in a Feature Film | Per Hallberg Karen Baker Landers Chris Jargo Mark L. Mangino Chris Hogan |

Won |

| Best Sound Editing - Effects & Foley, Domestic Feature Film | Per Hallberg Karen Baker Landers Craig S. Jaeger Jon Title Christopher Assells Dino Dimuro Dan Hegeman Michael A. Reagan Gregory Hainer Perry Robertson Peter Staubli Bruce Tanis Michael Hertlein Solange S. Schwalbe |

Won | |

| Plus Camerimage | Golden Frog | Salwomir Idziak | Nominated |

| Cinema Audio Society Award | Outstanding Sound Mixing for Motion Pictures | Michael Minkler Myron Nettinga Chris Munro |

Nominated |

| Directors Guild of America Award | Outstanding Directorial Achievement in Motion Pictures | Ridley Scott | Nominated |

| Golden Trailer Award | Best Drama | Trailer Park, Inc. | Nominated |

| MTV Movie Award | Best Movie | Nominated | |

| Best Action Sequence | First helicopter crash. | Nominated | |

| PFCS Award | Best Acting Ensemble | Eric Bana Ewen Bremner William Fichtner Josh Hartnett Jason Isaacs Ewan McGregor Sam Shepard Tom Sizemore |

Nominated |

| Best Cinematography | Salwomir Idziak | Nominated | |

| Best Film Editing | Pietro Scalia | Nominated | |

| Teen Choice Award | Film - Choice Actor, Drama/Action Adventure | Josh Hartnett | Nominated |

| Film - Choice Movie, Drama/Action Adventure | Nominated | ||

| World Soundtrack Award | Best Original Soundtrack of the Year | Hans Zimmer | Nominated |

| Soundtrack Composer of the Year | Nominated | ||

| Writers Guild of America Award | Best Screenplay Based on Material Previously Produced or Published | Ken Nolan | Nominated |

| ASCAP Award | Top Box Office Films | Hans Zimmer (also for The Ring) | Won |

| DVD Exclusive Award | Best Overall DVD, New Movie (Including All Extra Features) | Charles de Lauzirika (Deluxe Edition) | Nominated |

| Saturn Award | Best DVD Special Edition Release | Nominated |

Controversies and Inaccuracies

Soon after Black Hawk Down's release, the Somali Justice Advocacy Center in California denounced what they felt was its brutal and dehumanizing depiction of Somalis and called for its boycott.[3]

In a radio interview, Brendan Sexton, an actor who briefly appeared in the movie, said the version of the film which made it onto theater screens significantly differed from the one recounted in the original script. According to him, many scenes asking hard questions of the U.S. troops with regard to the violent realities of war, the true purpose of their mission in Somalia, etc., were cut out.[21]

In a review featured in The New York Times, film critic Elvis Mitchell expressed dissatisfaction with the film's "lack of characterization", and noted the film "reeks of glumly staged racism".[22] Owen Gleiberman and Sean Burns, the film critics for the mainstream magazine Entertainment Weekly and the alternative newspaper Philadelphia Weekly, respectively, echoed the sentiment that the depiction was racist.[23] Jerry Bruckheimer, the film's producer, rejected such claims on The O'Reilly Factor, putting them down to political correctness in part due to Hollywood's liberal leanings.[24]

Somali nationals charge that the African actors chosen to play the Somalis in the film do not in the least bit resemble the racially unique peoples of the Horn of Africa nor does the language they communicate in sound like the Afro-Asiatic tongue spoken by the Somali people. The abrasive manner in which lines are delivered and the film's inauthentic vision of Somali culture, they add, fails to capture the tone, mannerisms and spirit of actual life in Somalia. When shown to crowds of Somalis in Somalia, young men cheered whenever an American soldier's character was shot on screen.[12]

In an interview with the BBC, the faction leader Osman Ali Atto indicated that many aspects of the film are factually incorrect. He took exception with the ostentatious character chosen to portray him; Ali Atto does not look like the actor who portrayed him, smoke cigars, or wear earrings,[25] facts which were later confirmed by SEAL Team Six sniper Howard E. Wasdin in his 2012 memoirs. Wasdin also indicated that while the character in the movie ridiculed his captors, Atto in reality seemed concerned that Wasdin and his men had been sent to kill rather than apprehend him.[26] Atto additionally stated that he was not consulted about the project or approached for permission, and that the film sequence re-enacting his arrest contained several inaccuracies:[25]

First of all when I was caught on 21 September, I was only travelling with one Fiat 124, not three vehicles as it shows in the film[...] And when the helicopter attacked, people were hurt, people were killed[...] The car we were travelling in, (and) I have got proof, it was hit at least 50 times. And my colleague Ahmed Ali was injured on both legs[...] I think it was not right, the way they portrayed both the individual and the action. It was not right.[25]

Navy Seal Wasdin similarly remarked that while olive green military rigger's tape was used to mark the roof of the car in question in the movie, his team in actuality managed to track down Atto's whereabouts using a much more sophisticated technique involving the implantation of a homing device in a cane. The cane was then presented as a gift for Atto to a contact who routinely met with him, which eventually led the team directly to the faction leader.[26]

Malaysian military officials whose own troops were involved in the fighting have likewise raised complaints regarding the film's accuracy. Retired Brigadier-General Abdul Latif Ahmad, who at the time commanded Malaysian forces in Mogadishu, told the AFP news agency that Malaysian moviegoers would be under the wrong impression that the real battle was fought by the Americans alone, while Malaysian troops were "mere bus drivers to ferry them out".[27]

General Pervez Musharraf, who later became President of Pakistan after a coup, similarly accused the filmmakers of not crediting the work done by the Pakistani soldiers. In his autobiography In the Line of Fire: A Memoir, Musharraf wrote:

The outstanding performance of the Pakistani troops under adverse conditions is very well known at the UN. Regrettably, the film Black Hawk Down ignores the role of Pakistan in Somalia. When U.S. troops were trapped in the thickly populated Madina Bazaar area of Mogadishu, it was the Seventh Frontier Force Regiment of the Pakistan Army that reached out and extricated them. The bravery of the U.S. troops notwithstanding, we deserved equal, if not more, credit; but the filmmakers depicted the incident as involving only Americans.[28]

Rangers' return in 2013

In March 2013 two survivors from Task Force Ranger returned to Mogadishu with a film crew to shoot a short film titled BulletProof Faith - Rangers Return to "Black Hawk Down", which will debut in October 2013 on the 20th anniversary of the battle. Author Jeff Struecker and country singer Keni Thomas relived the battle as they drove through the Bakaara Market in armored vehicles and visited the Wolcott crash site.

References

- ^ a b "Black Hawk Down (2001)". Box Office Mojo. Amazon.com. Retrieved 2007-10-26.

- ^ "The 74th Academy Awards (2002) Nominees and Winners". Oscars.org. Retrieved 2011-11-19.

- ^ a b "Black Hawk Rising". ZMag.org. Retrieved 2011-02-21.

- ^ Hunter, Stephen (2009). Now Playing at the Valencia: Pulitzer Prize-Winning Essays on Movies. New York. p. 129. ISBN 978-0-7432-8201-7.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help)CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ The Hollywood Reporter. Vol. 401. 2007. p. 94.

{{cite news}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ Production Notes.

- ^ "Text of the decision from USCourts.gov". Retrieved 2011-02-21.

- ^ Turner, Megan (2001-11-18). "War-Film "Hero" Is A Rapist". New York Post. Retrieved 2006-12-10.

- ^ a b c d Rubin, Steven Jay (2011). "Black Hawk Down". Combat Films: American Realism, 1945-2010 (2 ed.). McFarland. pp. 257–262. ISBN 978-0-7864-5892-9.

- ^ Laurence, John Shelton (2008). "Operation Restore Honor in Black Hawk Down". Why we fought: America's wars in film and history. University Press of Kentucky. p. 431. ISBN 978-0-8131-9191-1.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|editors=ignored (|editor=suggested) (help) - ^ Raw, Laurence (2009). The Ridley Scott Encyclopedia. Lanham, Maryland. p. 209. ISBN 978-0-8108-6951-6.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help)CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ a b "Somalis flock to bootleg 'Black Hawk'". Retrieved 2011-02-21.

- ^ Institute for Social and Cultural Communications (2002). Z Magazine. 15 (1–6): 6.

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help); Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ Montalbano, Dave (2010). The Adventures of Cinema Dave in the Florida Motion Picture World. California. p. 541. ISBN 978-1-4500-2396-2.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help)CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Dinning, Mark. "Empire's Black Hawk Down Movie Review". EmpireOnline.com. Retrieved 2011-11-05.

- ^ Clark, Mike (2001-12-28). "Black Hawk' turns nightmare into great cinema". USA Today. Retrieved 2011-11-14.

- ^ "Black Hawk Down". Rotten Tomatoes. Flixter. Retrieved 2009-11-08.

- ^ "Black Hawk Down". Metacritic. CBS Interactive. Retrieved 2009-11-08.

- ^ (2008-12-12). "'Black Hawk Down': Arts and culture in the Bush era". TheDailyBeast.com. Retrieved 2011-10-23.

- ^ (2010-12-21). "Black Hawk Down, Down, Down: Three Perspectives on the Film". UncurledFist.com. Retrieved 2011-10-23.

- ^ "As 'Black Hawk Down' Director Ridley Scott Is Nominated for An Oscar, An Actor in the Film Speaks Out Against Its Pro-War Message". DemocracyNow.org. Retrieved 2011-02-21.

- ^ Mitchell, Elvis (2001-12-28). "Mission Of Mercy Goes Bad In Africa". The New York Times. Retrieved 2010-04-26.

- ^ "Sean Burns: "Ridley Scott and Jerry Bruckheimer's latest is racist crap"". PhiladelphiaWeekly.com. Retrieved 2011-02-21.

- ^ "Defending Black Hawk Down". FoxNews.com. 2002-01-15. Retrieved 2011-02-21.

- ^ a b c "Warlord thumbs down for Somalia film". BBC News. January 29, 2002. Retrieved February 3, 2012.

- ^ a b Wasdin, Howard (2011). SEAL Team Six – Memoirs of a US Navy Sniper. pp. 225–226.

- ^ "Jingoism jibe over Black Hawk Down". BBC News. 2002-01-21. Retrieved 2010-01-01.

- ^ Pervez Musharraf, In the Line of Fire: A Memoir, (Free Press: 2006), p. 76.

External links

- 2001 films

- American films

- American war films

- Battle of Mogadishu (1993)

- Columbia Pictures films

- English-language films

- War films

- Films about shot-down aviators

- Films directed by Ridley Scott

- Films produced by Jerry Bruckheimer

- Films set in 1993

- Films set in Somalia

- Films shot in Morocco

- Films that won the Best Sound Mixing Academy Award

- Films whose editor won the Best Film Editing Academy Award

- Revolution Studios films

- Scott Free Productions films

- Somali-language films

- War films based on actual events

- Film scores by Hans Zimmer