Keith Moon

Keith Moon | |

|---|---|

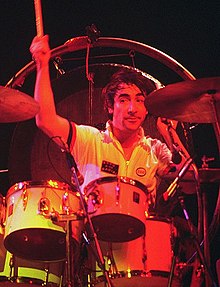

Keith Moon in 1975 | |

| Background information | |

| Birth name | Keith John Moon |

| Born | 23 August 1946 Wembley, London England, UK |

| Died | 7 September 1978 (aged 32) Westminster, London England, UK |

| Genres | Rock, art rock, hard rock, power pop |

| Occupation(s) | Musician, songwriter, producer, actor |

| Instrument(s) | Drums, percussion, vocals, bugle, trumpet, tuba |

| Years active | 1962–1978 |

Keith John Moon (23 August 1946[1] – 7 September 1978) was an English musician, best known for being the drummer of the English rock group The Who. He was known for his unique drumming style, playing zig-zag across the kit with a wash of cymbal, and gained notoriety for his eccentric and often self-destructive behaviour. In 2011, Moon was voted the second greatest drummer in history in a Rolling Stone's '"The Best Drummers of All Time'" readers' poll. His drumming skills continue to attract praise from critics and musicians alike, 35 years after his death.

Moon grew up in Wembley, London and took up drumming in the early 1960s. After performing with local band The Beachcombers, he joined The Who in 1964, before they had recorded their first single. He stayed with the band during their rise to fame, and was quickly recognised and praised for his distinctive drumming. He occasionally collaborated with other musicians, and later made appearances on radio and film, but he considered The Who his main occupation first and foremost, and remained a member until his death. In addition to his ability as a drummer, he developed a reputation for smashing his kit on stage and for destroying hotel rooms while on tour. He had a particular interest in blowing up toilets using cherry bombs or dynamite, and destroying television sets. He enjoyed touring and socialising, and attempted to live his entire life as one long party, being especially restless during the occasions that The Who were inactive. His 21st birthday party in Flint, Michigan has become a notable example of decadent behaviour amongst rock groups.

In the 1970s, Moon suffered from a number of tragedies, notably the accidental death of his chauffeur, Neil Boland, and the breakdown of his marriage. He became increasingly addicted to drink, particularly brandy and champagne, and started to acquire a reputation for decadence and dark humour, giving him the nickname "Moon The Loon". After relocating to Los Angeles during the mid-1970s with his personal assistant, Peter "Dougal" Butler, he attempted to make his only solo album, the poorly received Two Sides of the Moon. By the time of The Who's final tours in 1976, and particularly during filming of The Kids Are Alright and recording of Who Are You, the gradual deterioration of his condition started to show. He passed out on stage, and was hospitalised on several occasions. Moon moved back to London in 1978, and died in September after overdosing on Heminevrin, a drug designed to help curb alcohol abuse.

Early life

Moon was born on 23 August 1946 at Central Middlesex Hospital in north west London to Alfred Charles "Alf" and Kathleen Winifred "Kit" Moon,[1][2] and grew up in Wembley. As a boy he was hyperactive and had a restless imagination, with a particular fondness for the radio series The Goon Show and music. Moon failed his eleven plus exam, which prevented him attending a grammar school, and therefore went to Alperton Secondary Modern School.[3] In a report his art teacher commented, "Retarded artistically. Idiotic in other respects".[4] Teacher, Aaron Sofocleous, praised his music skills and encouraged his chaotic style, even if one school report noted, "He has great ability, but must guard against a tendency to show off".[4]

At age twelve, Moon joined his local Sea Cadet Corps band as a bugle player but traded his position to be a drummer. He also took an interest in practical jokes and home science kits, with a particular enthusiasm for explosions.[5] Often on his way home from school Keith would go to Macari's Music Studio in Ealing Road to practice on the drums there, where he learned his basic skills on the instrument. He left school around Easter 1961 aged 14,[6] and enrolled at Harrow Technical College, which led to a job repairing radios. He used money from this job to buy his first drum kit.[7]

Career

Early years

Moon took lessons from one of the loudest contemporary drummers, Screaming Lord Sutch's Carlo Little, at ten shillings a time.[8] Moon initially played in the drumming style of American surf rock and jazz, with a mix of R&B, using grooves and fills of those genres, exemplified by the noted Los Angeles studio drummer Hal Blaine. His favourite musicians were jazz artists, particularly Gene Krupa, whose flamboyant style he subsequently copied.[9] He also admired DJ Fontana, Ringo Starr, and The Shadows' original drummer, Tony Meehan.[10] As well as drumming, Moon was interested in singing, with a particular interest in Motown.[11] One band Moon notably idolised was The Beach Boys;[12] Roger Daltrey, one of Moon's bandmates in The Who, later said that even at the peak of The Who's fame, Moon would have left to drum for the Californian band if the opportunity had come up.[13]

During this time, Moon joined his first serious band, The Escorts, replacing his then best friend, Gerry Evans.[14] In December 1962, he joined The Beachcombers, a semi-professional London cover band who played rock'n'roll and hits by groups such as The Shadows.[15] During his time in the group, Moon incorporated various theatrical tricks into his act, including one instance where he "shot" the group's lead singer with a starter pistol.[16] The Beachcombers all had day jobs, including Moon, who was working in the sales department of British Gypsum. He had the most interest among the band members in turning fully professional, and thus in April 1964, aged 17,[17] he auditioned for The Who, who were looking for a permanent replacement for Doug Sandom. The Beachcombers continued as a local covers band after his departure.[18]

The Who

A commonly cited, though disputed, story of how Moon joined The Who is that he turned up to a gig shortly after Sandom's departure, where a session drummer was used. Dressed entirely in ginger clothes and with his hair dyed ginger (future bandmate Pete Townshend later described him as a "Ginger Vision"),[19]: 52:40 he claimed to his would-be bandmates that he could play better, and proceeded to play in the second half of the band's set, nearly demolishing the kit in the process.[20] Moon later claimed that he was never formally invited to drum with The Who permanently; when Ringo Starr asked how he had joined the band, he said he had "just been filling in for the last fifteen years".[19]: 52:29

Moon's arrival in The Who changed the dynamics of the group. Sandom had generally been the member to keep peace as Daltrey and Townshend feuded between themselves, but because of Moon's temperament, this no longer occurred, so the group now had four members who would frequently be in conflict. "We used to fight regularly", remembered Moon in later years. "John [Entwistle] and I used to have fights – it wasn't very serious, it was more of an emotional spur-of-the moment thing".[21] Moon also clashed with Daltrey and Townshend, saying "We really have absolutely nothing in common apart from music" in a later interview.[22] Although Townshend described him as a "completely different person to anyone I've ever met",[19]: 38:48 the pair did form a rapport in the early years, and enjoyed performing practical jokes and comedy improvisations together. Moon's style of playing affected The Who's musical structure, and while Entwistle initially found his lack of traditional timekeeping to be problematic, it created an original sound.[21]

Moon was particularly fond of touring with The Who, since it was the only chance he regularly got to socialise with his bandmates, and was generally restless and bored when he was not playing live. This would carry over to other aspects of his life later on, as he acted them out, according to biographer Marsh, "as if his life were one long tour".[23] Antics like these earned him the nickname "Moon the Loon".[24]

Musical contributions

I suppose as a drummer, I'm adequate. I've got no real aspirations to be a great drummer. I just want to play drums for The Who and that's it.

Keith Moon, Melody Maker, September 1970[25]

Moon's style of drumming was considered unique by his bandmates, though they sometimes found his lack of conventional playing to be frustrating, with Entwistle noting that he tended to play at a faster or slower tempo depending on what mood he was in.[26] "He wouldn't play across his kit," he later added. "He'd play zig-zag. That's why he had two set of tom-toms. He'd move his arms forward like a skier."[20] Daltrey said that Moon "just instinctively put drum rolls in places that other people would never have thought of putting them."[20]

Who biographer John Atkins states that the group's early test sessions for Pye Records in 1964 show that "they seemed to have understood just how important was ... Moon's contribution."[27] Contemporary critics questioned his ability to keep time, with biographer Tony Fletcher suggesting that the timing on Tommy was "all over the place". Who producer Jon Astley said "you didn't think he was keeping time, but he was".[26] Early recordings of Moon on the kit tended to make the drums sound tinny and somewhat disorganised,[28] and it was not until the recording of Who's Next, with Glyn Johns' no-nonsense production techniques and the requirement to keep to a strict-tempo synthesizer track, that he started developing a more disciplined performance in the studio. Fletcher considers the drumming on this album to be the best of Moon's career.[29]

Unlike several contemporary rock drummers such as Ginger Baker and John Bonham, Moon hated drum solos and refused to play them in concert. At one Who show, Townshend and Entwistle decided to spontaneously stop playing to hear Moon play a drum solo. Moon immediately stopped too, exclaiming, "Drum solos are boring!"[30]

Although not a strong vocalist, Moon was enthusiastic about singing and wanted to sing lead with the rest of the group.[31] While the other three members handled the vast majority of the vocals on stage, Moon would semi-regularly attempt to sing backing, particularly on I Can't Explain. He also liked to provide humorous commentary during song announcements, though sound engineer Bob Pridden preferred to mute his vocal microphone on the mixing desk where possible.[32] His propensity for making his bandmates laugh around the microphone led them to banish him from the studio when vocals were being recorded. This led to a game where Moon would sneak in to join the singing.[33] At the end of the song "Happy Jack", Townshend can be heard saying "I saw ya!" to Moon as he tries to sneak into the studio.[34] Moon's interest in surf music and his desire to sing lead led to him doing so on several early tracks, including "Bucket T" and "Barbara Ann" (Ready Steady Who EP, 1966),[35] and the high backing vocals on other songs, such as "Pictures of Lily". Moon's performance on "Bell Boy" (Quadrophenia, 1973) saw him abandon "serious" vocal performances to perform in character with an exaggerated character performance, which gave him, in Fletcher's words, "full licence to live up to his reputation as a lecherous drunk," adding it was "exactly the kind of performance the Who needed from him to bring them back down to earth."[36]

Moon was credited as composer of "I Need You", which he also sang, and the instrumental "Cobwebs and Strange" (from the album A Quick One, 1966),[37] the single B-sides "In The City" (co-written with Entwistle),[38] and "Girl's Eyes" (from The Who Sell Out sessions; featured on Thirty Years of Maximum R&B and a 1995 re-release of The Who Sell Out), "Dogs Part Two" (1969), "Tommy's Holiday Camp" (1969),[39] and "Waspman" (1972).[40] Moon also co-composed the instrumental "The Ox" (from the debut album My Generation) with Townshend, Entwistle and keyboardist Nicky Hopkins. The song "Tommy's Holiday Camp" (from Tommy) was credited to Moon, who suggested the action should take place in a holiday camp.[41] The song was written by Townshend, and although there is a misconception that Moon sings on the track, the version on the album is Townshend's demo.[42]

Moon is credited with producing the violin solo on the song "Baba O'Riley".[43] He sat in with a gig with East of Eden at the Lyceum, playing congas, and afterwards suggested the idea of performing on the track to the group's violinist, Dave Arbus.[44]

Equipment

Moon typically played four, then five-piece kits during the early part of his career.[46] His 1965 set consisted of Ludwig drums and Zildjian cymbals. By 1966, he was feeling the limitations of this setup, and was inspired by Ginger Baker's double bass drum to move to a larger Premier kit.[45]: 1 This setup was notable for not having a hi-hat as Moon exclusively used the crash and ride cymbals instead. Moon remained a loyal customer to Premier, and continued to use their drums for the remainder of his career.[47]

Moon's Classic Red Sparkle Premier setup comprised two 22 in (560 mm) bass drums, three 14 in (360 mm) mounted toms, one 16 in (410 mm) floor tom, a 14 in (360 mm) Ludwig Supraphonic 400 snare Moon's classic cymbal setup consisted of two Paiste Giant Beat 18 in (460 mm) crashes and one 20 in (510 mm) ride.[48] This kit was used at the Who's performance at the Monterey Pop Festival in 1967.[45]: 2 From 1967 to 1969, Moon used the "Pictures Of Lily" drum kit, named after its artwork, which had a 22 in (560 mm) bass drum, two 16 in (410 mm) floor toms and three mounted toms.[45]: 3 In recognition of his loyalty to the company during his lifetime, Premier reissued this kit in 2006 under the name Spirit of Lily.[47]

By 1970, Moon had expanded his setup to include timbales, gongs and timpani, and proceeded to use a similar configuration for the remainder of his career.[45]: 3 In 1973, Premier's marketing promotion manager, Eddie Haynes, started working directly with Moon and consulting with him over specific requirements.[45]: 2 At one point, Moon demanded that Premier make a white kit with gold-plated fillings. Haynes claimed this would be prohibitively expensive, but Moon simply replied, "Dear boy, do exactly as you feel it should be, but that's the way I want it." The kit was eventually fitted with copper fillings,[45]: 2 and was later given to a young Zak Starkey.[49]

Destroying instruments and other stunts

During an early gig in the Railway Tavern, after Townshend had accidentally broken his guitar and had proceeded to smash it, the audience were keen for him to repeat the event. Moon responded by kicking his drum kit over.[50] Subsequent early live sets culminated in what they later described as "auto-destructive art", with the band, particularly Moon and Townshend, destroying their equipment in elaborate fashion. Following the Railway Tavern performance, Moon showed a zeal for auto destructive art, zestfully kicking and smashing his drums, claiming he did so because he was fed up of a lack of reaction from audiences.[51] Reflecting on this, Townshend later said "A set of skins is about $300 [then £96] and after every show he'd just go bang, bang, bang and then kick the whole thing over."[52]

In May 1966, Moon discovered that Bruce Johnston from The Beach Boys, who was visiting London, had an early copy of their album Pet Sounds with him. He found John Lennon and Paul McCartney at a club, and persuaded them to come with him to the Waldorf Hotel, where Johnston was staying, to listen to the album together. A few days later, Moon took Johnston to the set of Ready Steady Go!, which caused him and Entwistle to be late for a gig with The Who that evening. During the finale of My Generation, a physical altercation broke out on stage between Moon and Townshend, which was reported on the front page of the New Musical Express the following week. Moon and Entwistle subsequently left The Who for a week, with Moon looking to join The Animals or The Nashville Teens, but both changed their minds and returned.[53]

On the Who's early US package tour at the RKO Theatre in New York during March and April 1967, he performed five shows a day, kicking over his drumkit after every show.[54] Later that year, during their appearance on The Smothers Brothers Comedy Hour US television show, Moon bribed a stagehand to load gunpowder into one of his bass drums, putting in around ten times the standard dose.[55] During the finale of "My Generation", he kicked the drum off the riser and then set off the charge. The intensity of the explosion singed Townshend's hair and embedded a piece of cymbal in Moon's arm.[56] This clip subsequently became the opening scene in the film The Kids Are Alright.[19]: 7:44

Though Moon acquired a reputation for kicking over his drum kit, Haynes claimed that it was done carefully and that his kit rarely needed to be repaired. He did recall that stands and foot pedals needed regularly replacing, saying that Moon "would go through them like a knife through butter."[45]: 2

Other work

Music

While Moon generally stated he was only interested in working with The Who,[25] he did participate in outside musical projects. In 1966, Moon worked with Yardbirds guitarist Jeff Beck, pianist Nicky Hopkins, and future Led Zeppelin members Jimmy Page and John Paul Jones to record an instrumental, "Beck's Bolero", which was released as the B-side to "Hi Ho Silver Lining" and appeared on the album Truth. Moon also played timpani on another track, a cover of Jerome Kern's, "Ol' Man River". He was credited on the back of the album as You Know Who.[57]

Moon may have inspired the name for the band Led Zeppelin. When he was briefly considering leaving The Who in 1966, he had been chatting to Entwistle and Page about forming a supergroup. Moon or Entwistle remarked that a particular suggestion had gone down like a "lead zeppelin" (i.e. "lead balloon"). Although the supergroup was never formed, Page remembered the expression and later adopted it as the name of a new band.[58]

The Beatles became friends with Moon and this led to occasional collaborations. In 1967, Moon contributed brush drums to their single "All You Need Is Love".[59] On 15 December 1969, he joined John Lennon's Plastic Ono Band for a live performance at the Lyceum Theatre) in London for a UNICEF charity concert. In 1972, this performance was released as a companion disc to Lennon's and Ono's album Some Time In New York City.[60]

The continuing friendship with Entwistle led to Moon making an appearance on Smash Your Head Against the Wall, Entwistle's first solo album and the first by any member of The Who. Moon did not play drums on the album, which was covered by Jerry Shirley, and restricted himself to percussion.[61] Rolling Stone's John Hoegel praised Entwistle's decision not to let Moon drum, saying it helped distance the album from the familiar sound of The Who.[62]

Moon became involved in solo work when he moved to Los Angeles in the mid-1970s. In 1974, Track Records/MCA released a Moon solo single that covered The Beach Boys songs "Don't Worry, Baby" and "Teenage Idol". The following year, he released his only solo album, entitled Two Sides of the Moon. Although it featured Moon singing, most of the drumming was left to others including Ringo Starr, session musicians Curly Smith and Jim Keltner and actor/musician Miguel Ferrer. Moon played drums on only three tracks.[63] The album had a negative reception from critics. NME's Roy Carr wrote, "Moonie, if you didn't have talent, I wouldn't care; but you have, which is why I'm not about to accept Two Sides of the Moon.[64] Dave Marsh, reviewing the album in Rolling Stone, wrote "There isn't any legitimate reason for this album's existence."[65] During one of his few drum solo performances on television, for ABC's Wide World, Moon played a five minute drum solo using transparent acrylic drums filled with water and goldfish, and dressed as a cat. When asked by an audience member what would happen to the kit, he joked that "even the best drummers get hungry."[66] His performance did not go down well with animal lovers, and several called the station to complain.[66]

Film

In the 2007 documentary film Amazing Journey: The Story of The Who, Daltrey and Townshend stated that Moon had a talent for dressing up as a variety of various characters and embodying them. They recount how Moon often dreamed of getting out of music to be a Hollywood film actor,[11] though Daltrey also added that he did not consider Moon to have the necessary patience and work ethic for a professional. Who manager Bill Curbishley agreed, believing that Moon "wasn't disciplined enough to actually turn up or commit to doing the stuff."[67]

Despite these concerns, Moon landed himself several acting roles. The first of these came in 1971, when he had a cameo role in Frank Zappa's film 200 Motels as a nun fearful of dying from a drug overdose. Though the film only took 13 days to film, fellow cast member Howard Kaylan recalls Moon spending a substantial amount of off-camera time at the Kensington Garden Hotel bar, rather than sleeping.[68] His next film role came in 1973, when Moon was featured in the film That'll Be the Day, playing the character J.D. Clover, the drummer at a holiday camp during the early days of British rock 'n' roll in a fictional band called Stray Cats.[69] Moon reprised the Clover role for the sequel Stardust the following year.[70] He also appeared as the character "Uncle Ernie" in Ken Russell's 1975 film adaptation of Tommy.[71]

Destructive behaviour

When you've got money and you do the kind of things I get up to, people laugh and say that you're eccentric, which is a polite way of saying you're fucking mad.

Keith Moon[72]

Moon led a very destructive lifestyle. From the first days of The Who, he began taking amphetamines,[73] and in an early interview for the New Musical Express listed his favourite food as "French Blues".[74] He spent his share of the band's income madly, began visiting Soho clubs such as the Speakeasy and the Bag o' Nails regularly, and the combination of pills and alcohol would continue to escalate into alcoholism and drug addiction later in life.[75] "[We] went through the same stages everybody goes through – the bloody drug corridor," he later reflected, adding "Drinking suited the group a lot better".[76]

According to Townshend, Moon began destroying hotel rooms when The Who were staying at the Hilton in Berlin on tour in autumn 1966.[77] As well as hotels, Moon went on to destroy the homes of friends and even his own home, throwing furniture out of high windows and setting fire to buildings. Andrew Neill and Matthew Kent estimated that his destruction of hotel toilets and plumbing ran as high as £300,000.[78] These destructive acts, often fuelled by drugs and alcohol, were Moon's way of expressing his eccentricity; he enjoyed shocking the public with them. Longtime friend and personal assistant Butler observed "he was trying to make people laugh and be Mr Funny, he wanted people to love him and enjoy him, but he would go so far. Like a train ride you couldn't stop."[79]

Once, while riding in a limousine on the way to an airport, Moon insisted they return to their hotel, saying, "I forgot something." On reaching the hotel, he ran back to his room, grabbed the television, and threw it out the window into the swimming pool below. He then left the hotel and jumped back into the limo, sighing, "I nearly forgot."[80]

Exploding toilets

Moon's favourite stunt was to flush powerful explosives down toilets. According to Fletcher, Moon's toilet pyrotechnics began in 1965 when he purchased 500 cherry bombs.[81] Over time, Moon graduated from cherry bombs to M-80 fireworks to sticks of dynamite, which became his explosive of choice.[82] "All that porcelain flying through the air was quite unforgettable," Moon recalled. "I never realised dynamite was so powerful. I'd been used to penny bangers before."[81] Moon quickly developed a reputation of destroying bathrooms and completely annihilating the toilets. The destruction mesmerized Moon and enhanced his public image as rock and roll's premier hellraiser. Fletcher goes on to state that, "no toilet in a hotel or changing room was safe" until Moon had exhausted his supply of explosives.[81]

On one occasion, Townshend walked into a hotel bathroom where Moon was staying, and noticed the toilet had disappeared, with just an S bend remaining. In response, Moon explained that a cherry bomb was about to detonate, so he threw it down the pan. He proceeded to present a case of five hundred bombs. "And of course from that moment on", recalled Townshend, "we got thrown out of every hotel we ever stayed in."[83]

Entwistle recalled being close to Moon on tour, stating "I suppose we were two of a kind" ... "We shared a room on the road and got up to no good,"[84] and consequently the two of them were often involved blowing up toilets together. In a 1981 interview with the Los Angeles Times, he confessed, "A lot of times when Keith was blowing up toilets I was standing behind him with the matches."[85] In Alabama, Moon and Entwistle loaded a toilet with cherry bombs after being told that they could not receive room service. According to Entwistle, "That toilet was just dust all over the walls by the time we checked out. The management brought our suitcases down to the gig and said: 'Don't come back ...'"[84]

A hotel manager once called Moon in his room and asked him to lower the volume on his cassette recorder, because there was "too much noise." In response, Moon asked him up to his room, excused himself to the bathroom, put a lit stick of dynamite in the toilet, and shut the bathroom door. Upon returning, he asked the manager to stay as he wanted to explain something. Following the explosion, Moon turned the recording back on and proclaimed, "That was noise. This is The 'Oo."[86]

Flint Holiday Inn incident

On 23 August 1967, while on tour as the opening act for Herman's Hermits, Moon reached new levels of excess at a Holiday Inn hotel in Flint, Michigan.[81] They were celebrating Moon's 21st birthday, although it was believed to be his 20th at the time. Entwistle later said, "He decided that if it was a publicised fact that it was his 21st birthday, he would be able to drink."[87]

Moon immediately began drinking upon arriving in Flint. The Who spent the afternoon visiting local radio stations with Nancy Lewis, then the band's publicist. Moon later posed for a photo outside the Holiday Inn in front of the "Happy Birthday Keith" sign erected by the hotel's management. According to Lewis, Moon was very drunk by the time the band took to the stage at the Atwood High School football stadium.[88]

Upon returning to the hotel, Moon decided to start a food fight, and soon, cake began flying through the air. The evening culminated in Moon's knocking his front tooth out. At a nearby hospital, doctors could not give him anaesthetic due to his inebriated state and he had to endure the removal of the remainder of the tooth without it. Back at the hotel, a melee erupted with fire extinguishers set off, guests and objects thrown into the swimming pool, and a piano reportedly destroyed. The chaos was halted only when police arrived, handguns drawn.[88]

A furious Holiday Inn management presented the groups with a bill for $24,000, which was reportedly settled either by Herman's Hermits or tour manager Edd McCann.[89] Townshend claimed that The Who were banned for life from all of the hotel properties,[90] but Fletcher claimed that they stayed at a Holiday Inn in Rochester, New York only a week later. Fletcher also disputes the widely held belief that Moon drove a Lincoln Continental into the hotel's swimming pool, a claim that Moon himself made in a Rolling Stone interview in 1972.[89]

Passing out on stage

Moon's wild lifestyle began to undermine his health and his reliability as a band member. During the 1973 Quadrophenia tour, at The Who's debut US date in the Cow Palace Arena, Daly City, California, Moon ingested a large mixture of tranquillisers and brandy. In a 1979 interview, Townshend claimed that Moon had consumed Ketamine pills,[92] while Fletcher claims he took PCP. During the concert, Moon passed out on his drum kit while the band was playing the song "Won't Get Fooled Again". The band stopped playing and a group of roadies carried Moon offstage. They gave him a shower and an injection of cortisone, then sent him back onstage after a thirty-minute delay. Moon passed out for good during the song "Magic Bus" and was again removed from the stage. The band continued without him for a few songs. Finally, Townshend asked, "Can anyone play the drums? – I mean somebody good". A drummer in the audience, Scot Halpin, came up and played for the rest of the show.[93]

At the opening date of the band's March 1976 US tour in Boston Garden, Moon passed out over his drumkit after two numbers, which resulted in the gig being rescheduled a week later. The next evening, Moon systematically destroyed everything in his hotel room, cut himself in doing so, and subsequently passed out. He was discovered by manager Bill Curbishley, who took him to hospital, explaining to Moon that "I'm gonna get the doctor to get you nice and fit, so you're back within two days. Because I want to break your fucking jaw ... You have fucked this band around so many times and I'm not having it any more."[94] Curbishley was told by doctors that, had he not intervened, Moon would have bled to death.[95] Who biographer Marsh suggests that it was at this point that Daltrey and Entwistle seriously considered firing Moon, but decided that doing so would make his life even worse.[96]

During the band's recording sabbatical between 1975 and 1978, Moon gained much weight.[97] Nonetheless, Entwistle maintained that Moon and The Who reached their prime live peak during 1975 and 1976. Even so, by the close of the 1976 US tour in Miami that August, Moon became delirious, and was admitted to the Hollywood Memorial Hospital for eight days. The group was concerned that he would be unable to continue the last leg of the tour, which ended at the Maple Leaf Gardens, Toronto on 21 October – his last ever public gig.[91] By the time of the group's invitation-only gig at the Kilburn Gaumont in December 1977, intended for The Kids are Alright, he was visibly overweight and had difficulty keeping a solid performance.[98] After recording Who Are You, Townshend refused to follow up the album with a tour until Moon had stopped drinking,[99] and explained that if Moon's playing did not improve quickly, he would be sacked.[100] Daltrey later denied that the threat of firing happened, but did concede that by this time, Moon was simply out of control.[101]

Financial problems

Owing to The Who's early stage act being reliant on smashing instruments, and Moon's enthusiasm for destroying hotels, the group were in debt for much of the 1960s: Entwistle estimates they ran at a continual loss of around £150,000.[102] Even when the group became relatively financially stable after Tommy, Moon continued to rack up debts. He bought numerous cars and gadgets, and ran close to bankruptcy.[23] His recklessness with money meant that his profit from the group's 1975 UK tour ran to a mere £47.35.[103]

Personal life and relationships

Birthdate

Before the release of "Dear Boy: The Life of Keith Moon" by Fletcher in 1998, many assumed that Moon's date of birth was 23 August 1947. This erroneous date appeared in several otherwise reliable sources, such as the Townshend-authorised biography "Before I Get Old: The Story of The Who."[104] The incorrect date had been propagated by Moon in interviews, and accepted as correct, before Fletcher disproved it after his thorough research, showing that Moon was in fact born in 1946.[1]

Kim Kerrigan

Moon's first serious relationship was with Kim Kerrigan, who he started dating in January 1965 after she saw The Who play at the Disc A Go Go in Bournemouth.[105] By the end of the year, she discovered she was pregnant, and her parents, who were furious, met with the Moons to discuss options. She decided to move into the Moon family home in Wembley.[106] They were married on 17 March 1966 at Brent Registry Office,[107] and their daughter Amanda was born on 12 July.[108] The marriage and daughter were kept a secret from the press until May 1968.[109] He was occasionally violent towards Kim;[110] "If we went out after I had Mandy," she later recalled, "if someone talked to me, he'd lose it. We'd go home and he'd start a fight with me."[111] He loved Amanda, but his regular absence through touring and fondness for practical jokes translated to an uneasy relationship with her as a very young girl. "He had no idea how to be a father," remembered Kim, adding "he was too much of a child himself".[109]

From 1971 to 1975, Moon owned Tara, a home in Chertsey, where he initially lived with his wife and daughter.[112] The Moons maintained an extravagant social life at that house, including numerous cars. Jack McCullogh, then working for the Who's record label Track Records, recalls Moon demanding he find and purchase a milk float to store in the garage at Tara.[113]

In 1973, Kim, convinced that neither she nor anyone else could moderate Keith's behaviour, left her husband, taking Amanda with her.[114] She eventually moved in with Faces keyboard player Ian McLagan.[115] Biographer Marsh believes that Moon never truly recovered from the departure of his family.[116] Butler concurs, noting that despite his later relationship with Annette Walter-Lax, he believes Kim was the only woman Moon loved.[79] She died in a car accident in Austin, Texas on 2 August 2006.[117]

Annette Walter-Lax

In 1975, Moon began a relationship with Swedish model Annette Walter-Lax. Of their relationship, she later said that Moon was "so sweet when he was sober, that I was just living with him, in the hope that he would kick all this craziness."[72] On one occasion, she begged Malibu neighbour Larry Hagman to check Moon into yet another clinic to dry out (as he had tried more than once before), but when doctors recorded Moon's intake at breakfast (a full bottle of champagne along with Courvoisier and amphetamines), they concluded there was no hope in his rehabilitation.[118]

Friends

Moon enjoyed being the life and soul of any party. Manager Curbishley remembers that "he wouldn't walk into any room and just listen. He was an attention seeker and he had to have it."[67]

Early in The Who's career, Moon got to know The Beatles, and would join them at clubs, forming a particularly close friendship with Ringo Starr.[119] Later, he became friends with Vivian Stanshall and "Legs" Larry Smith, who had both been members of the Bonzo Dog Doo Dah Band. They would regularly drink and perform practical jokes together. Smith remembers one occasion where he and Moon tore a pair of trousers apart, only for an accomplice to come in looking for one-legged trousers.[120]

Guitarist Joe Walsh recorded chats with Moon, finding it remarkable how witty and alert the inebriated drummer managed to stay, ad-libbing his way through surrealistic fantasy stories à la Peter Cook, which Cooper reaffirms, saying he was not even certain he ever knew the real Keith Moon, or if there was one.[121] In 1974, Moon struck up a friendship with actor Oliver Reed, while working on the movie version of Tommy.[122] While Reed was able to match Moon's drinking, he was also able to appear on set the next morning to deliver a perfect performance, whereas Moon would cost several hours of filming time.[67]

Dougal Butler

Peter 'Dougal' Butler started working for The Who in 1967, and became Moon's personal assistant the following year,[123] with a general remit of helping him stay out of trouble. He recalls managers Kit Lambert and Chris Stamp saying "We trust you with Keith but if you ever want any time off, for a holiday or some sort of rest, let us know and we'll pay for it," though Butler never took them up on the offer.[79]

Butler followed Moon to Los Angeles when he relocated there, but felt that the drug culture prevalent at the time became a severe detriment to Moon's health, later saying "my job was to have eyes in the back of my head."[123] Townshend agrees, stating that by 1975, Butler had "no influence over him whatsoever."[124] Though he was a loyal companion to Moon, the lifestyle eventually got too much for him, so he phoned up Curbishley, saying that they both needed to move back to England or one of them might die.[79] He eventually left Moon's services in 1978.[123]

Neil Boland

On 4 January 1970, Moon was involved in a car-pedestrian death outside the Red Lion pub in Hatfield, Hertfordshire. Pub patrons had begun to attack his Bentley and the drunk Moon started driving the car to escape them. During the fracas, Moon ran over and killed his friend, driver, and bodyguard, Neil Boland. After an investigation, the coroner ruled Boland's death as an accident. Moon received an absolute discharge after being charged with driving offences.[125]

Those close to Moon said that he was haunted by Boland's death for the rest of his life. According to Pamela Des Barres, Moon had nightmares about the incident that woke both of them during the night. Immediately after waking, Moon would say that he had no right to be alive.[126]

Death

In mid 1978, Moon moved into a flat in Curzon Place (now called Curzon Square), Shepherd Market, Mayfair, London, renting from Harry Nilsson. Cass Elliot had died there four years earlier,[127][128] and Nilsson was concerned about letting the flat to Moon, believing it to be cursed because of her death. Townshend disagreed, and assured him that "lightning wouldn't strike the same place twice."[129]

After moving into the flat, Moon began taking a regular prescribed course of clomethiazole (Heminevrin), a sedative, to alleviate his alcohol withdrawal symptoms. He desperately wanted to detox from alcohol; due to his fear of a psychiatric hospital, he wanted to do it at home. Clomethiazole is discouraged for unsupervised detoxification because of its addictiveness, its tendency to induce drug tolerance, and its risk of death when mixed with alcohol.[130] The pills were prescribed by Dr. Geoffrey Dymond, who was unaware of Moon's behaviour. Dymond gave Moon a full bottle of 100 pills, and instructed him to take one pill whenever he felt a craving for alcohol (but not more than three pills per day).[131]

By September 1978, Moon was even having difficulty playing drums, according to roadie Dave "Cy" Langston. After going in the studio to overdub drums for The Kids Are Alright, Langston later said "after two or three hours, he got more and more sluggish, he could barely hold a drumstick."[132]

On 6 September, Moon and Walter-Lax were guests of Paul and Linda McCartney at a preview of the film The Buddy Holly Story. After dining with the McCartneys at Peppermint Park in Covent Garden, Moon and Walter-Lax returned to their flat. Moon watched a film, The Abominable Dr. Phibes, and told Walter-Lax to cook him a breakfast of steak and eggs. When she objected, Moon replied "If you don't like it, you can fuck off!" These turned out to be his last words.[127] Moon then took 32 tablets of clomethiazole (Heminevrin). When she went to check on him the following afternoon, she discovered he was dead.[133]

Curbishley phoned the flat at around 5 pm, intending to speak to Moon, but instead got hold of Dymond, who gave him the grave news. He informed Townshend, who in turn informed the rest of the band. Entwistle was giving an interview to French journalists at the time, when he was interrupted by news of Moon's death on the phone. Attempting to tactfully and quickly close the interview down, he broke down in tears when the journalist asked him about future plans for The Who.[134]

Moon died shortly after the release of Who Are You. On the album cover, he is seated on a chair back-to-front to hide the weight gained over three years; the words "not to be taken away" appear on the back of the chair.[135]

The police determined there were 32 pills of clomethiazole in Moon's system, the digestion of six of these being sufficient to cause his death; the other 26 were still undissolved when he died.[131] Moon was cremated on 13 September 1978, at Golders Green Crematorium in London, and his ashes were scattered in its Gardens of Remembrance.[136]

Townshend was instrumental in convincing Daltrey and Entwistle to carry on touring as The Who, though he later admitted this was probably a way of coping with Moon's death and suggested it was "completely irrational, bordering on insane." Allmusic's Bruce Eder stated "When Keith Moon died, the Who carried on and were far more competent and reliable musically, but that wasn't what sold rock records."[137] [129] In November 1978, Small Faces/Faces drummer Kenney Jones became an official member of The Who. Townshend later said that Jones "was one of the new British drummers who could fill Keith's shoes",[138] though Daltrey was less keen, saying Jones "wasn't the right style".[139] Keyboardist John "Rabbit" Bundrick, who had already rehearsed with Moon earlier in the year,[99] joined the live band as an unofficial member.[140][141]

Jones left The Who in 1988[142] and drummer Simon Phillips toured with the band the following year. Phillips has since praised Moon's ability to drum over the backing track of "Baba O'Riley".[143] Since 1994, the Who's drummer has been Ringo Starr's son Zak Starkey. Starkey learned to drum from Moon, whom he called "Uncle Keith", when he was a teenager.[144]

The London 2012 Summer Olympic Committee contacted The Who manager Bill Curbishley about Moon performing at the games, 34 years after his death. In an interview with The Times, Curbishley quipped, "I emailed back saying Keith now resides in Golders Green crematorium, having lived up to The Who's anthemic line 'I hope I die before I get old' ... If they have a round table, some glasses and candles, we might contact him."[145]

Legacy

Moon's drumming has frequently drawn praise from critics. Author Nick Talevski described him as "the greatest drummer in rock," adding "he was to the drums what Jimi Hendrix was to the guitar."[146] Holly George-Warren, editor and author of The Rock and Roll Hall of Fame: The First 25 Years, argues: "With the death of Keith Moon in 1978, rock arguably lost its single greatest drummer."[147] According to Eder, "Moon, with his manic, lunatic side, and his life of excessive drinking, partying, and other indulgences, probably represented the youthful, zany side of rock & roll, as well as its self-destructive side, better than anyone else on the planet."[137] Dave Marsh's The New Book of Rock Lists ranks Moon at No. 1 on its list of The 50 Greatest Rock 'n' Roll Drummers.[148] Similarly, he was ranked at No. 2 on Rolling Stone's "The Best Drummers of All Time" readers poll in 2011.[149] Adam Budofsky, editor of Drummer magazine, has stated his performances on Who's Next and Quadrophenia "represent a perfect balance of technique and passion" and that "there's been no drummer who's touched his unique slant on rock and rhythm since."[150]

Several rock drummers have cited Moon as an influence, including Neil Peart[151] and Dave Grohl.[152] The Jam paid tribute to Moon on the second single from their third album, "Down in the Tube Station at Midnight", in which the B-side of the single is a cover song from The Who: "So Sad About Us", and the back cover of the record is a photo of Moon's face; the Jam's record was released about a month after Moon's death.[153] Animal, one of puppeteer Jim Henson's characters from the Muppets TV show and movies, has been said by several sources to have been based on Keith Moon, due to the fact that both share similar hair, eyebrows, outrageous personality and wild drumming style.[154][155]

"God bless his beautiful heart ..." Ozzy Osbourne told Sounds a month after the drummer's death. "People will be talking about Keith Moon 'til they die, man. Someone somewhere will say, 'Remember Keith Moon?' Who will remember Joe Bloggs who got killed in a car crash? No one. He's dead, so what? He didn't do anything to talk of."[156]

In 1998, Fletcher published a biography of Moon entitled Dear Boy: The Life of Keith Moon in the United Kingdom. The phrase "Dear Boy" had become a catchphrase of Moon's when he started affecting a pompous English accent, influenced by Lambert. In 2000, the book was released in the U.S. under the title Moon (The Life and Death of a Rock Legend). Q Magazine said the book was "Horrific and terrific reading," while Record Collector said the book was "one of rock's great biographies."[157]

In 2008, English Heritage declined an application for Moon to be awarded a blue plaque. Speaking to The Guardian, Sir Christopher Frayling said they "decided that bad behaviour and overdosing on various substances wasn't a sufficient qualification". The Heritage Foundation disagreed with the decision and decided on their own deal to present a plaque, which was unveiled on 9 March 2009. Daltrey, Townshend, Robin Gibb and Kit Moon were present at the ceremony.[82][158]

Discography

- Solo albums

- Two Sides of the Moon (1975)

References

- ^ a b c Fletcher 1998, p. 1.

- ^ Neill & Kent 2009, p. 13.

- ^ Fletcher 1998, p. 9.

- ^ a b Fletcher 1998, p. 11.

- ^ Fletcher 1998, p. 20.

- ^ Fletcher 1998, p. 22.

- ^ Fletcher 1998, p. 29.

- ^ "Obituaries: Carlo Little". Daily Telegraph. 17 August 2005. Retrieved 30 August 2013.

- ^ Fletcher 1998, p. 237.

- ^ Neill & Kent 2009, p. 11.

- ^ a b Amazing Journey: The Story of The Who. Universal Pictures Video. 26 November 2007. ASIN B000WBP282.

- ^ Bogovich & Posner 2003, p. 24.

- ^ Colothan, Scott (2 April 2009). "Roger Daltrey: 'Keith Moon Would've Left The Who for The Beach Boys'". http://www.gigwise.com/. Gigwise. Retrieved 28 April 2013.

{{cite news}}: External link in|website=|publisher=(help) - ^ Fletcher 1998, p. 38.

- ^ Fletcher 1998, p. 46.

- ^ Fletcher 1998, pp. 48–66.

- ^ Case 2010, p. 146.

- ^ Fletcher 1998, pp. 71–75.

- ^ a b c d The Who (1979). The Kids Are Alright (movie). England: Jeff Stein, Sydney Rose.

- ^ a b c Chapman 1998, p. 70.

- ^ a b Marsh 1989, p. 87.

- ^ Ewbank, Tim; Hildred, Stafford (2012). Roger Daltrey: The biography. Hachette UK. p. 28. ISBN 978-1-4055-1845-1.

- ^ a b Marsh 1989, p. 354.

- ^ Case 2010, p. 145.

- ^ a b Fletcher 1998, p. 238.

- ^ a b Fletcher 1998, p. 234.

- ^ Atkins 2000, p. 35.

- ^ John Atkins. Who's Next (2003 remaster) (Media notes). Polydor. p. 23.

{{cite AV media notes}}: Unknown parameter|publisherid=ignored (help) - ^ Fletcher 1998, p. 286.

- ^ Fletcher 1998, p. 401.

- ^ Marsh 1989, p. 183.

- ^ Charlesworth, Chris (1995). Live at Leeds (CD reissue) (Media notes). Polydor. p. 8.

{{cite AV media notes}}: Unknown parameter|publisherid=ignored (help) - ^ Marsh, Dave; Stein, Kevin (1981). The book of rock lists. Dell Pub. Co. ISBN 978-0-440-57580-1.

- ^ Fletcher 1998, p. 174.

- ^ Atkins 2000, p. 75.

- ^ Fletcher 1998, p. 346.

- ^ Atkins 2000, p. 80.

- ^ Atkins 2000, p. 71.

- ^ Neill & Kent 2009, p. 296.

- ^ Atkins 2000, p. 173.

- ^ Fletcher 1998, p. 230.

- ^ Schaffner, Nicholas (1982). The British Invasion: From the First Wave to the New Wave. McGraw-Hill. p. 127. ISBN 978-0-07-055089-6.

- ^ Who's Next (back sleeve credits) (Media notes). Track Records.

{{cite AV media notes}}: Unknown parameter|publisherid=ignored (help) - ^ O'Connor, Mike (2012). "Interview with Ron Caines And Geoff Nicholson". Friars Aylesbury official site. Retrieved 11 April 2013.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Doerschuk, Andy (October / November 1989). "Keith Moon's Love/Hate Relationship With His Drum Set". Drum Magazine. Retrieved 9 September 2013.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ "Keith Moon's drums – early kits". WhoTabs. Retrieved 6 April 2013.

- ^ a b "Premier Spirit of Lily 8 Piece Kit". Music Radar. 6 December 2007. Retrieved 10 April 2013.

- ^ "Premier double-bass kit : Keith Moon". WhoTabs. Retrieved 6 April 2013.

- ^ Fletcher 1998, p. 462.

- ^ Marsh 1989, p. 125.

- ^ Marsh 1989, p. 126.

- ^ Marsh 1989, p. 267.

- ^ Fletcher 1998, pp. 156–160.

- ^ Marsh 1989, pp. 241, 247.

- ^ Marsh 1989, p. 275.

- ^ Marsh 1989, p. 276.

- ^ "Truth (review)". Classic Rock magazine. July 2005: 44. Retrieved 30 August 2013.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Fletcher 1998, p. 225.

- ^ "Keith Moon Records With The Beatles". Keith Moon Movie. Retrieved 3 September 2012.

- ^ Miles, Barry (2009). The Beatles Diary Volume 1: The Beatles Years. Music Sales Group. p. 798. ISBN 978-0-85712-000-7.

- ^ "Smash Your Head Against The Wall (credits)". AllMusic. Retrieved 22 July 2013.

- ^ Hoegel, John (9 December 1971). "Smash Your Head Against The Wall". Rolling Stone: 58.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Fletcher 1998, pp. 402–406.

- ^ Fletcher 1998, p. 428.

- ^ Fletcher 1998, p. 429.

- ^ a b Neill & Kent 2009, p. 259.

- ^ a b c Chapman 1998, p. 80.

- ^ Fletcher 1998, p. 280.

- ^ Neill & Kent 2009, p. 219.

- ^ Neill & Kent 2009, p. 247.

- ^ Stewart, John (2006). Broadway Musicals, 1943–2004. McFarland. p. 4456. ISBN 978-1-4766-0329-2.

- ^ a b Fletcher 1998, p. Inset between p. 436 and 437.

- ^ Marsh 1989, p. 165.

- ^ Marsh 1989, p. 178.

- ^ Marsh 1989, p. 224.

- ^ Marsh 1989, p. 262.

- ^ Townshend 2012, p. 94.

- ^ Neill & Kent 2009, p. 265.

- ^ a b c d "Interview with Dougal Butler by Mark Raison". 4 July 2012. Retrieved 6 April 2013.

- ^ "10 bizarre rock'n'roll anecdotes". New Musical Express. 21 May 2010. Retrieved 30 August 2013.

- ^ a b c d e Fletcher 1998, p. 194.

- ^ a b Osley, Richard (12 March 2009). "Who's vexed? Rival 'blue plaque' for Moon puts heritage row centre stage". Camden New Journal. Retrieved 28 August 2013.

- ^ Marsh 1989, p. 270.

- ^ a b Jones, Lesley-Ann (12 July 2007). "My friend John, the rock star who DID die before he got old". Daily Mail. London. Retrieved 23 July 2013.

{{cite news}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|work=(help) - ^ Boucher, Geoff (28 June 2002). "John Entwistle, 57; Innovative Bass Player Co-Founded the Who". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 7 May 2010.

- ^ Fletcher 1998, p. 435.

- ^ Fletcher 1998, p. 195.

- ^ a b Fletcher 1998, p. 196.

- ^ a b Fletcher 1998, pp. 196–197.

- ^ Townshend 2012, p. 37.

- ^ a b Fletcher 1998, pp. 464–466.

- ^ "Rolling Stone". 14 July 1979.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Fletcher 1998, pp. 361–362.

- ^ Marsh 1989, p. 475.

- ^ Fletcher 1998, p. 457.

- ^ Marsh 1989, p. 476.

- ^ Marsh 1989, p. 492.

- ^ Marsh 1989, p. 494.

- ^ a b Townshend 2012, p. 264.

- ^ Marsh 1989, p. 496.

- ^ Chapman 1998, p. 84.

- ^ Marsh 1989, p. 304.

- ^ Fletcher 1998, p. 441.

- ^ Marsh 1989, p. 80.

- ^ Fletcher 1998, p. 112.

- ^ Fletcher 1998, pp. 139–141.

- ^ Fletcher 1998, p. 146.

- ^ Fletcher 1998, p. 163.

- ^ a b Fletcher 1998, p. 220.

- ^ Fletcher 1998, p. 184.

- ^ Fletcher 1998, p. 186.

- ^ Fletcher 1998, p. 290.

- ^ Fletcher 1998, p. 295.

- ^ Fletcher 1998, p. 352.

- ^ Fletcher 1998, p. 365.

- ^ Marsh 1989, p. 413.

- ^ Ian Herbert (4 August 2006). "Iconic model who married Keith Moon dies in car crash". The Independent. Retrieved 6 April 2013.

- ^ Fletcher 1998, pp. 424–425.

- ^ Fletcher 1998, p. 127.

- ^ Fletcher 1998, pp. 245–246.

- ^ Fletcher 1998, p. 393.

- ^ Fletcher 1998, pp. 388–389.

- ^ a b c Interview with Dougal Butler by Richard T. Kelly, from Full Moon: The Amazing Rock and Roll Life of Keith Moon. Faber & Faber. 2012. ISBN 978-0-571-29585-2. Retrieved 9 April 2013.

- ^ Townshend 2012, p. 248.

- ^ Marsh 1989, p. 355.

- ^ Des Barres, Pamela (2005). I'm with the Band: Confessions of a Groupie (2nd ed.). Chicago Review Press. pp. 254–258. ISBN 1-55652-589-3.

- ^ a b Wilkes, Roger (2001). "Inside story: 9 Curzon Place". Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 2 January 2008.

- ^ "Shepherd Market History". Shepherdmarket.co.uk. Retrieved 22 October 2011.

- ^ a b Townshend 2012, p. 268.

- ^ Aronson, J K, ed. (2009). Meyler's Side Effects of Psychiatric Drugs. Elsevier. p. 439. ISBN 978-0-444-53266-4.

- ^ a b Fletcher 1998, p. 524.

- ^ Neill & Kent 2009, p. 292.

- ^ Fletcher 1998, p. 517.

- ^ Fletcher 1998, p. 518.

- ^ Fletcher 1998, p. 504.

- ^ Fletcher 1998, p. 522.

- ^ a b Eder, Bruce. "Keith Moon Biography". Allmusic. Retrieved 26 July 2013.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ Townshend 2012, p. 287.

- ^ Townshend 2012, p. 288.

- ^ Atkins 2000, p. 27.

- ^ Townshend 2012, p. 289.

- ^ Prato, Greg. "Kenny Jones - biography". Allmusic. Retrieved 30 August 2013.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ Chapman 1998, p. 79.

- ^ "Artist biography : Zak Starkey". Zildjian (official site). Retrieved 30 August 2013.

- ^ "London 2012 organisers wanted Keith Moon to play at Olympics ceremony". The Guardian. 13 April 2012. Retrieved 26 July 2013.

- ^ Talevski, Nick (2010). Rock Obituaries - Knocking On Heaven's Door. Omnibus Press. p. 437. ISBN 978-0-85712-117-2.

- ^ Holly George-Warren. The Rock and Roll Hall of Fame: The First 25 Years. Page 54.

- ^ The New Book of Rock Lists. Google Books. 1 November 1994. ISBN 978-0-671-78700-4. Retrieved 22 October 2011.

- ^ Greene, Andy (February 2011). "Rolling Stone Readers Pick Best Drummers of All Time". Rolling Stone. Retrieved 12 February 2011.

- ^ Budofsky, Adam (2006). The Drummer : 100 Years of Rhythmic Power And Invention. Hal Leonard Corporation. p. 63. ISBN 978-1-4234-0567-2.

- ^ Anatomy of a Drum Solo DVD, Neil Peart (2005) accompanying booklet. (Republished in Modern Drummer Magazine, April 2006)

- ^ Light, Alan (13 November 2009). "Dave Grohl in the New York Times". The New York Times. Retrieved 22 October 2011.

- ^ Fletcher 1998, p. 521.

- ^ "Myers 'to play' Who's Keith Moon". BBC News. 30 September 2005.

- ^ Bogovich & Posner 2003, p. 89.

- ^ "Interview with Ozzy Osbourne". Sounds. 21 October 1978.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ "Dear Boy : The Life of Keith Moon". Amazon. Retrieved 6 April 2013.

- ^ Michaels, Sean (2 February 2009). "The Who's Keith Moon to be honoured with 'blue plaque'". The Guardian. Retrieved 28 August 2013.

Bibliography

- Atkins, John (2000). The Who on Record: A Critical History, 1963–1998. McFarland. ISBN 978-0-7864-0609-8.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Bogovich, Richard; Posner, Cheryl (2003). The Who: A Who's Who. McFarland & Company. ISBN 978-0-7864-1569-4. Retrieved 28 April 2013.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Case, Case (2010). Out of Our Heads: Rock 'n' Roll Before the Drugs Wore Off. Hal Leonard Corporation. ISBN 978-1-61780-123-5.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Chapman, Rob (1998). "Moon : The Ultimate Rock Disaster Epic" (PDF) (58). Mojo.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help); Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Marsh, Dave (1989). Before I Get Old: The Story of The Who. Plexus Publishing Ltd. ISBN 978-0-85965-083-0.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Fletcher, Tony (1998). Dear Boy: The Life of Keith Moon. Omnibus Press. ISBN 978-1-84449-807-9.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Neill, Andrew; Kent, Matthew (2009). Anyway, Anyhow, Anywhere: The Complete Chronicle of the WHO 1958–1978. Sterling Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4027-6691-6.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Townshend, Pete (2012). Who Am I: A Memoir. HarperCollins. ISBN 978-0-06-212726-6.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

Further reading

- Full Moon by Dougal Butler (Faber, 2012)

- The Who: Maximum R&B by Richard Barnes and Pete Townshend, Plexus Publishing; 5th edition (27 September 2004)