Mesa (computer graphics)

| Original author(s) | Brian Paul |

|---|---|

| Developer(s) | Intel, AMD, VMware (previously Tungsten Graphics)[1] |

| Initial release | August 1993[2] |

| Stable release | 10.2.6

/ August 19, 2014[3] |

| Preview release | 10.3 RC1

/ August 21, 2014[4] |

| Repository | |

| Written in | C, C++, Assembly[5] |

| Operating system | Cross-platform (Linux, BSDs, Haiku, et al.) |

| Type | Graphics library |

| License | MIT License[6] |

| Website | mesa3d |

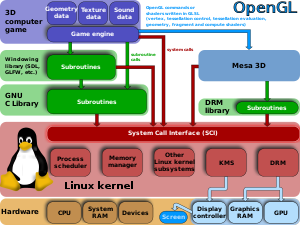

Mesa is a collection of free and open-source libraries that implement several rendering as well as video acceleration APIs related to hardware-accelerated 3D rendering, 3D computer graphics and GPGPU, the most prominent being OpenGL. Mesa is hosted at freedesktop.org and used on Linux, BSD and other operating systems. Additionally to the APIs, Mesa also harbors most of the available free and open-source graphics device drivers. The development of Mesa started in August 1993 by Brian Paul, who still maintains the project, by now containing numerous contributions from various other people and companies worldwide, due to its broad adoption. Crowdfunding has been successfully used to partially drive development of Mesa.[7]

Software architecture

Implementations of rendering APIs

Mesa is known as housing implementation of graphic APIs. Historically the main API that Mesa has implemented is OpenGL, along with other Khronos Group related specifications (like OpenVG, OpenGL ES or recently EGL). But Mesa can implement other APIs and indeed it did with Glide. There had been patches to support Direct3D Windows API, but neither of those are currently in the main line.

The supported version of the different graphic APIs depends on the driver, because each hardware driver has its own implementation (and therefore status). This is specially true for DRI drivers, while the Gallium3D drivers share common code that tend to homogenize the supported extensions and versions.

Mesa 10 complies with OpenGL 3.3, for Intel, AMD/ATI and Nvidia GPU hardware. It has not yet achieved full OpenGL 4 compliance at any level.[9] Mesa maintains a support matrix with the status of the current OpenGL 3 conformance.[10]

| API | OpenGL | OpenGL ES | OpenVG | EGL | GLX | Glide | Direct3D | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Current Version | Date | 4.5 2014-08-11 |

3.1 2014-03-17 |

1.1 2008-12-03 |

1.5 2014-03-19 |

1.4 2005-12-16 |

3.10 2013-04-03 |

11.2 2011-09-13 |

| 10.2 | (2014-06-06)[11] | 3.3[12] | 3.0 | 1.1 | 1.4 | 1.4 | deprecated | 9.0c |

| 10.1 | (2014-03-04)[13] | 3.3[14] | 3.0 | 1.1 | 1.4 | 1.4 | deprecated | 9.0c |

| 10.0 | (2013-11-30)[15] | 3.3[16] | 3.0 | 1.1 | 1.4 | 1.4 | deprecated | 9.0c |

| 9.0 | (2012-10-08) | 3.1[17] | 2.0 | 1.1 | 1.4 | 1.4 | ? | ? |

| 8.0 | (2012-02-08) | 3.0 | 2.0 | 1.1 | 1.4 | 1.4 | ? | ? |

| 7.0 | (2007-06-22) | 2.1 | — | — | — | 1.4 | ? | ? |

| 6.0 | (2004-01-06) | 1.5 | — | — | — | 1.3 | ? | ? |

| 5.0 | (2002-11-13) | 1.4 | — | — | — | 1.3 | ? | ? |

| 4.0 | (2001-10-22) | 1.3 | — | — | — | 1.3 | ? | ? |

Old version, not maintained Old version, still maintained Latest version Future release | ||||||||

There has also been a Direct3D 9 state tracker since July, 2013. [18]

Generic Buffer Management

Generic Buffer Management (GBM) is an API which provides a mechanism for allocating buffers for graphics rendering tied to Mesa. GBM is intended to be used as a native platform for EGL on drm or openwfd. The handle it creates can be used to initialize EGL and to create render target buffers.[19]

Mesa GBM is an abstraction of the graphics driver specific buffer management APIs (for instance the various libdrm_* libraries), implemented internally by calling into the Mesa GPU drivers.

For example, the Wayland compositor Weston does its rendering using OpenGL ES 2, which it initializes by calling EGL. Since the server runs on the "bare KMS driver", it uses the EGL DRM platform, which could really be called as the GBM platform, since it relies on the Mesa GBM interface.

Implementations of video acceleration APIs

There are three possible ways to do the calculations necessary for the encoding and decoding of video streams:

- use a codec and do calculations on the CPU

- use a codec and do calculations on the 3D rendering engine of the GPU

- use a SIP block designed specifically for this task, e.g. PureVideo, Unified Video Decoder, Video Codec Engine, Quick Sync Video, DaVinci, CedarX, Crystal HD, etc.

Utilizing the CPU doesn't require any special support to be present in Mesa, but methods two and three do require explicit support by the graphics device driver and additional special interfaces (APIs) to be used by end-user software to access this hardware, which are shared in Mesa 3D. A couple of APIs for the access of video decoding hardware have been designed, e.g.

- Video Decode and Presentation API for Unix (VDPAU) – by Nvidia

- Video Acceleration API (VAAPI) – by Intel

- Distributed Codec Engine (DCE) – by Texas Instruments

- DirectX Video Acceleration (DXVA) – Microsoft Windows-only

- OpenMAX IL – video encoding by Khronos Group

- OpenVideo Decode (OVD) – AMD vaporware

- X-Video Bitstream Acceleration (XvBA) – extension to Xv

- X-Video Motion Compensation (XvMC) – extension to Xv

One of this interfaces is then used by end-user software, like e.g. VLC media player, GStreamer or HandBrake, to access the video acceleration hardware and make use of it.

Please note, that V4L2 is a kernel-to-user-space interface for video bit streams delivered by webcams or TV tuners.

Nouveau supports PureVideo and provides access to it through VDPAU and partly through XvMC.[20]

The free radeon driver supports Unified Video Decoder and Video Codec Engine through VDPAU and OpenMAX.[21]

Device drivers

The available free and open-source device drivers for graphic chipsets are "stewarded" by Mesa (because the existing free and open-source implementation of APIs are developed inside of Mesa). Currently there are two frameworks to write graphics drivers: DRI and Gallium3D.

There are device drivers for AMD/ATI R100 to R800, Intel, and Nvidia cards with 3D acceleration. Previously drivers existed for the IBM/Toshiba/Sony Cell APU of the PlayStation 3, S3 Virge & Savage chipsets, VIA chipsets, Matrox G200 & G400, and more.[22]

The free and open-source drivers compete with proprietary closed-source drivers. Depending on the availability of hardware documentation and man-power, the free and open-source driver lag behind more or less in supporting 3D acceleration of new hardware. Also, 3D rendering performance is usually significantly slower [1][2][3][4][5], with some notable exceptions, where the free and open-source driver perform better than the vendor drivers.

Direct Rendering Infrastructure (DRI)

At the time 3D graphics cards became more mainstream for PCs, individuals partly supported by some companies began working on adding more support for hardware-accelerated 3D rendering to Mesa.[when?] The Direct Rendering Infrastructure (DRI) was one of these approaches to interface Mesa, OpenGL and other 3D rendering API libraries with the device drivers and hardware. After reaching a basic level of usability, DRI support was officially added to Mesa. This significantly broadened the available range of hardware support achievable when using the Mesa library.[23]

With adapting to DRI, the Mesa library finally took over the role of the front end component of a full scale OpenGL framework with varying backend components that could offer different degrees of 3D hardware support while not dropping the full software rendering capability. The total system used many different software components.[23]

While the design requires all these components to interact carefully, the interfaces between them are relatively fixed. Nonetheless, as most components interacting with the Mesa stack are open source, experimental work is often done through altering several components at once as well as the interfaces between them. If such experiments prove successful, they can be incorporated into the next major or minor release. That applies e.g. to the update of the DRI specification developed in the 2007-2008 timeframe. The result of this experimentation, DRI2, operates without locks and with improved back buffer support. For this, a special git branch of Mesa was created.[24]

Gallium3D

Gallium3D was developed by Tungsten Graphics as a means to simplify the writing of device drivers and also to achieve maximum portability of them, without having to rewrite the source code. The main disadvantage is, that by introducing additional interfaces, namely the Gallium3D WinSys Interface, the full capabilities of the underlying hardware can not be accessed by the device drivers.[citation needed]

Software renderer

Mesa also contains an implementation of software rendering.

Mega driver

Mega driver was proposed by Emil Velikov. The concept boils down to bundling multiple drivers into a single big (hence the "mega") shared library.[25] The state trackers for VDPAU and XvMC have become separate libraries.[26]

Performance

History

Project initiator Brian Paul was a graphics hobbyist. He thought it would be fun to implement a simple 3D graphics library using the OpenGL API, which he might then use instead of VOGL (very ordinary GL Like Library).[2] Beginning in 1993, he spent eighteen months of part-time development before he released the software on the Internet. The software was well received, and people began contributing to its development. Mesa started off by rendering all 3D computer graphics on the CPU. Despite this, the internal architecture of Mesa was designed to be open for attaching to graphics processor-accelerated 3D rendering. In this first phase, rendering was done indirectly in the display server, leaving some overhead and noticeable speed lagging behind the theoretical maximum. The Diamond Monster 3D, using the Voodoo Graphics chipset, was one of the first 3D hardware devices supported by Mesa.

The first true graphics hardware support was added to Mesa in 1997, based upon the Glide API for the once new 3dfx Voodoo I/II graphics cards and their successors.[23] A major problem of using Glide as the acceleration layer was the habit of Glide to run full screen, which was only suitable for computer games. Further, Glide took the lock of the screen memory, and thus the display server was blocked from doing any other GUI tasks.[27]

See also

References

- ^ David Marshall (2008-12-16). "VMware's year end acquisition of Tungsten Graphics". InfoWorld. Retrieved 08-06-2011.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ a b "Mesa Introduction". Mesa Team. Retrieved 24 January 2013.

- ^ "Mesa 10.2.6 announce".

- ^ "Mesa 10.3 RC1 Release Announcement".

- ^ "Mesa". Ohloh. Retrieved 08-06-2011.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ "Mesa3D license".

- ^ "Improve OpenGL support for the Linux Graphics Drivers - Mesa". Indiegogo. 11 December 2013.

- ^ "AMD exploring new Linux driver Strategy". 22 March 2014. Retrieved 23 March 2014.

- ^ "Nine Reasons Mesa 9.0 Is Disappointing For End-Users". 9 October 2012.

- ^ http://cgit.freedesktop.org/mesa/mesa/tree/docs/GL3.txt

- ^ "[Mesa-announce] Mesa 10.2 released".

- ^ "Mesa 10.2 features". Phoronix. 6 June 2014.

- ^ "[Mesa-announce] Mesa 10.1 released".

- ^ "Mesa 10.1 features". Phoronix. 5 March 2014.

- ^ "[Mesa-announce] Mesa 10.0 released".

- ^ "http://www.phoronix.com/scan.php?page=news_item&px=MTQ5NjA".

{{cite web}}: External link in|title= - ^ http://www.mesa3d.org/relnotes/9.0.html

- ^ http://www.phoronix.com/scan.php?page=news_item&px=MTQxMjk

- ^ "libgbm in the Debian repositories".

- ^ "Nouveau Video Acceleration". freedesktop.org.

- ^ "Radeon Feature Matrix". freedesktop.org.

- ^ Direct Rendering Infrastructure Status Page on freedesktop.org

- ^ a b c Brian Paul (10 August 2000). "Introduction to the Direct Rendering Infrastructure". dri.sourceforge.net. Retrieved 25 January 2012.

- ^ "DRI2". X.org. Retrieved 25 January 2012.

- ^ "Megadrivers galore". freedesktop.org. 17 June 2014.

- ^ "VDPAU & XvMC state trackers are now separate libraries". 23 June 2014.

- ^ "What's the relationship between Glide and DRI?". dri.freedesktop.org. Retrieved 25 January 2012.

External links

- Official website

- The history of Mesa, by Jake Edge, October 2013

| User mode | User applications | bash, LibreOffice, GIMP, Blender, 0 A.D., Mozilla Firefox, ... | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| System components | init daemon: OpenRC, runit, systemd... |

System daemons: polkitd, smbd, sshd, udevd... |

Window manager: X11, Wayland, SurfaceFlinger (Android) |

Graphics: Mesa, AMD Catalyst, ... |

Other libraries: GTK, Qt, EFL, SDL, SFML, FLTK, GNUstep, ... | |

| C standard library | fopen, execv, malloc, memcpy, localtime, pthread_create... (up to 2000 subroutines)glibc aims to be fast, musl aims to be lightweight, uClibc targets embedded systems, bionic was written for Android, etc. All aim to be POSIX/SUS-compatible. | |||||

| Kernel mode | Linux kernel | stat, splice, dup, read, open, ioctl, write, mmap, close, exit, etc. (about 380 system calls)The Linux kernel System Call Interface (SCI), aims to be POSIX/SUS-compatible[1] | ||||

| Process scheduling subsystem | IPC subsystem | Memory management subsystem | Virtual files subsystem | Networking subsystem | ||

| Other components: ALSA, DRI, evdev, klibc, LVM, device mapper, Linux Network Scheduler, Netfilter Linux Security Modules: SELinux, TOMOYO, AppArmor, Smack | ||||||

| Hardware (CPU, main memory, data storage devices, etc.) | ||||||

- ^ "Admin Guide README". Kernel.org git repositories.

- Use dmy dates from November 2010

- Direct Rendering Infrastructure

- Free computer libraries

- Free software programmed in C

- Free system software

- Freedesktop.org

- OpenGL

- Software using the MIT license

- 1993 software

- Software written in assembly language

- Free 3D graphics software

- Graphics libraries

- Rendering APIs available on Linux