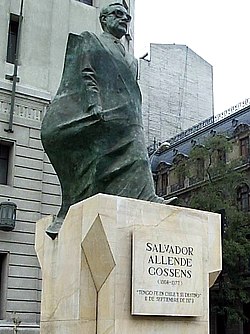

Salvador Allende

Salvador Allende Gossens | |

|---|---|

| File:Allende-Presidente-crop.jpg | |

| In office November 4, 1970 – September 11 1973 | |

| Preceded by | Eduardo Frei Montalva |

| Succeeded by | Augusto Pinochet |

| Personal details | |

| Born | July 26, 1908 Valparaíso |

| Died | September 11 1973 Santiago |

| Nationality | Chilean |

| Political party | Socialist |

| Spouse | Hortensia Bussi Soto |

Salvador Isabelino del Sagrado Corazón de Jesús Allende Gossens (July 26, 1908 – September 11, 1973) was President of Chile from September 1970 until his removal from power and death in September 1973.

Allende's career in Chilean government spanned nearly forty years. As a Socialist Party politician, he became a senator, deputy, cabinet minister and, following the 1970 presidential election, President of Chile. He had also stood for the presidency on three previous occasions, in 1952, 1958 and 1964.

As President, Allende is generally considered to have imposed a controversial populist, socialist, and pro-Cuban and pro-Soviet Union agenda. Domestic opposition and intervention from the United States led to a state of civil unrest amid strikes, lockouts, American economic sanctions and calls by some opposition members for the military to restore order. Less than a month after his condemnation by the Chamber of Deputies of Chile's Resolution of August 22, 1973, on September 11, 1973, a violent military coup d'etat took place, led by the then-Commander of the Army, Gen. Augusto Pinochet. Allende died during the coup, but the manner of his death has never been confirmed.

Early life

Allende was born in 1908 in Valparaíso. He was the son of Salvador Allende Castro and Laura Gossens Uribe. Allende attended high school at the Liceo Eduardo de la Barra in Valparaíso and medical school at the University of Chile, graduating with a medical degree in 1933. He also co-founded the Socialist Party of Chile in Valparaíso and became its leader. He married Hortensia Bussi, with whom he had three daughters.

In 1938, Allende became a minister of Health in the Popular Front government of Chile led by Pedro Aguirre Cerda, relinquishing the parliamentary seat for Valparaíso he had won in 1937. Around that time he wrote La Realidad Médico Social de Chile (The social and medical reality of Chile). Following Aguirre's death in 1941, he returned to parliament.

In 1945, Allende became senator for the Valdivia, Llanquihue, Chiloé, Aisén and Magallanes provinces; then for Tarapaca and Antofagasta in 1953; for Aconcagua and Valparaíso in 1961; and once more for Chiloé, Aisén and Magallanes in 1969. He had been president of the Chilean Senate from 1966.

His three unsuccessful bids for the presidency (in the 1952, 1958 and 1964 elections) prompted Allende to joke that his epitaph would be "Here lies the next President of Chile." In 1952, as candidate for the Frente de Acción Popular (Popular Action Front, FRAP), he obtained only 5.4% of the vote, partly due to a division within socialist ranks over support for Carlos Ibáñez and the prohibition of communism. In 1958, again as the FRAP candidate, Allende obtained 28.5% of the vote. This time, his defeat was attributed to votes lost to the populist Antonio Zamorano. In 1964, once more as the FRAP candidate, he lost again, polling 38.6% of the votes against 55.6% for Christian Democrat Eduardo Frei. As it became clear that the election would be a race between Allende and Frei, the political right – which initially had backed Radical Julio Durán – settled for Frei as "the lesser evil".

Allende was not an ardent Marxist but an outspoken critic of capitalism, which made him deeply unpopular within the administrations of successive U.S. presidents, from John F. Kennedy to Richard Nixon. They believed there was a danger of Chile becoming a communist state and joining the Soviet Union's sphere of influence; according to Vasili Mitrokhin's archive, Allende had been codenamed "LEADER" as a KGB contact, supplying the KGB with information since the 1950s. Senator Allende condemned the Soviet invasion of Hungary (1956) and Czechoslovakia (1968), and as President of Chile was the first Government in continental America to recognize the People's Republic of China (1971), then the main adversary of the Soviet Union. The United States had substantial economic interests in Chile, through corporations such as ITT, Anaconda and Kennecott. The Nixon administration feared that these companies might be nationalized or expropriated by a socialist government, so they were strongly opposed to Allende, a hostility that Nixon admitted openly. During Nixon's presidency, U.S. officials attempted to prevent Allende's election by financing political parties aligned with conservative candidate Jorge Alessandri and supporting strikes in the mining and transportation sectors.

Election

Allende finally won the 1970 Chilean presidential election as leader of the Unidad Popular ("Popular Unity") coalition. On September 4, 1970, he obtained a narrow plurality of 36.2 percent to 34.9 percent over Jorge Alessandri, a former president, with 27.8 percent going to a third candidate (Radomiro Tomic) of the Christian Democratic Party (PDC), whose electoral platform was quite close to Allende's. According to the Chilean Constitution of the time, if no presidential candidate obtained a majority of the popular vote, the Congress would choose the winner from among the two candidates with the highest number of votes. The tradition was for the Congress to vote for the candidate with the highest popular vote, regardless of margin. Indeed, former president Jorge Alessandri had been elected in 1958 with only 31.6 percent of the popular vote, defeating Allende.

The superpowers — the USSR and the United States — were invested in the result of the election. The KGB spent $420,000 in the campaign unbeknownst to Allende, while ITT gave at least $350,000 to Jorge Alessandri. The Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) was confident in Alessandri's victory, and did not see the need to fund Alessandri directly.

However, the results of September 4 were so disastrous for the right that U.S. President Richard Nixon ordered the CIA to develop plans to impede Allende's election, known as "Track One" and "Track Two". After the 1970 election, the Track One operation attempted to incite Chile's outgoing president, Eduardo Frei Montalva, to persuade his party (PDC) to vote in Congress for Alessandri. Under the plan, Alessandri would resign his office immediately after assuming it and call new elections. Eduardo Frei would then be constitutionally able to run again (since the Chilean Constitution did not allow a president to hold two consecutive terms, but allowed multiple non-consecutive ones), and presumably easily defeat Allende.

However the Congress chose Allende as president, on the condition that he would sign a "Statute of Constitutional Guarantees" affirming that he would respect and obey the Chilean Constitution, and that his socialist reforms would not undermine any element of it.

Allende assumed the presidency on November 3, 1970. Twelve days before, General René Schneider, Commander in Chief of the Chilean Army, was wounded during the Track Two operation. He was a known defender of the "Constitutionalism", a doctrine according to which the Army's role is exclusively professional, its mission being to protect the country's sovereignty and not being allowed to interfere in politics. The Track Two plan consisted in influencing the Chilean military to move against Allende. General Schneider's resistance while being kidnapped terminated in his death in a hospital, three days later, not being able to recover from gunshot wounds. [1]

Presidency

After his inauguration, Allende began to carry out his platform of implementing sweeping socialist programs in Chile, called La vía chilena al socialismo ("the Chilean Way to Socialism"). This included nationalization of large-scale industries (notably copper mining and banking), a thorough reform of the health care system, a reform of the educational system, a program of free milk for children, and a furthering of his predecessor Eduardo Frei Montalva's agrarian reform. [2]

The government announced a moratorium on foreign debt payments and defaulted on debts held by international creditors and foreign governments. Allende also froze all prices while raising salaries. Allende's implementation of these policies led to strong opposition by landowners, some middle-class sectors, the rightist National Party, the Roman Catholic Church (which was displeased with the direction of educational policy [3]), and eventually the Christian Democrats.

Allende also undertook Project Cybersyn, a system of networked telex machines and computers. Cybersyn was developed by British cybernetics expert Stafford Beer. The network transmitted data from factories to the government in Santiago, allowing for economic planning in real-time.

The land reforms that Allende highlighted as one of the central policies of his government had already begun under his predecessor Eduardo Frei Montalva, who had expropriated between one-fifth and one-quarter of all properties liable to takeover [Collier & Sater, 1996]. The Allende government's intention was to seize all holdings of more than eighty basic irrigated hectares [Faundez, 1988]. Allende also intended to improve the socio-economic welfare of Chile's poorest citizens. A key element was to provide employment, either in the new nationalised enterprises or on public works projects.

In the first year of Allende's term, the short-term economic results of Minister of the Economy Pedro Vuskovic's expansive monetary policy were unambiguously favorable: 12% industrial growth and an 8.6% increase in GDP, accompanied by major declines in inflation (down from 34.9% to 22.1%) and unemployment (down to 3.8%). However, these results were not sustained, and in 1972, the Chilean escudo had runaway inflation of 140%. The average Real GDP contracted between 1971 and 1973 at an annual rate of 5.6% ("negative growth"); and the government's fiscal deficit soared while foreign reserves declined [Flores, 1997]. The combination of inflation and government-mandated price-fixing, together with the "disappearance" of basic commodities from supermarket shelves, led to the rise of black markets in rice, beans, sugar, and flour. [4]

In 1971, following the re-establishment of diplomatic relations with Cuba, despite a previously established Organization of American States convention that no nation in the Western Hemisphere would do so (the only exception being Mexico, which had refused to adopt that convention), Cuban president Fidel Castro took a month-long visit to Chile. The visit, in which Castro participated actively in the internal politics of the country, holding massive rallies and giving public advice to Allende, was seen by those on the political right as proof to support their view that "The Chilean Way to Socialism" was an effort to put Chile on the same path as Cuba.

October 1972 saw the first of what were to be a wave of confrontational strikes. One, by owners of trucks, was joined by small businessmen, some (mostly professional) unions, and some student groups. Other than the inevitable damage to the economy, the chief effect of the 24-day strike was to induce Allende to bring the head of the army, general Carlos Prats, into the government as Interior Minister. [5]. A CIA report released in 2000 admitted that the CIA financed the trucker's strike.

In addition to the earlier-discussed provision of employment, Allende also raised wages on a number of occasions throughout 1970 and 1971. These rises in wages were negated by continuing increases in prices for food. Although price rises had also been high under Frei (27% a year between 1967 and 1970), a basic basket of consumer goods rose by 120% from 190 to 421 escudos in one month alone, August 1972. In the period 1970-72, while Allende was in government, exports fell 24% and imports rose 26%, with imports of food rising an estimated 149% [figures are from Nove, 1986, pp4-12, tables 1.1 & 1.7]. Although nominal wages were rising, there was not a commensurate increase in the standard of living.

Export income fell due to a decline in the price of copper on international markets; copper being the single most important export (more than half of Chile's export receipts were from this sole commodity [Hoogvelt, 1997]). Adverse fluctuation in the international price of copper negatively affected the economy throughout 1971-2: The price of copper fell from a peak of $66 per ton in 1970 to only $48-9 in 1971 and 1972 [Nove, 1986].

Throughout his presidency, Allende remained at odds with the Chilean Congress, which was dominated by the Christian Democratic Party. The Christian Democrats had campaigned on a left-wing platform in the 1970 elections, but they began to drift more and more towards the right during Allende's presidency, eventually forming a coalition with the right-wing National Party. They continued to accuse Allende of leading Chile toward a Cuban-style dictatorship and sought to overturn many of his more radical policies. Allende and his opponents in Congress repeatedly accused each other of undermining the Chilean Constitution and acting undemocratically.

Allende's increasingly bold socialist policies (partly in response to pressure from some of the more radical members within his coalition), combined with his close contacts with Cuba, heightened fears in Washington. The Nixon administration began exerting economic pressure on Chile via multilateral organizations, and continued to back Allende's opponents in the Chilean Congress. Almost immediately after his election, Nixon directed CIA and U.S. State Department officials to "put pressure" on Allende's government.

The coup

There were rumors of a possible deposement since at least 1972: In 1973, partly due to Allende's anti-market and anti-private property policies and partly as a result of the rapidly declining price of copper (Chile's main export), the economy took a major downturn. By September, hyperinflation (508% for the entire year) and shortages had plunged the country into near chaos [Flores, 1997].

Despite declining economic indicators, Allende's Popular Unity coalition actually increased its vote to 43% in the parliamentary elections early in 1973. However, by this point what had started as an informal alliance with the Christian Democrats [6] was anything but: the Christian Democrats now leagued with the right-wing National Party to oppose Allende's government, the two parties calling themselves the Confederación Democrática (CODE). The conflict between the executive and legislature paralyzed initiatives from either side. [7]

On June 29, 1973, a tank regiment under the command of Colonel Roberto Souper surrounded the presidential palace (La Moneda) in an unsuccessful coup attempt. [8] On August 9 General Carlos Prats was made Minister of Defense, but this decision proved so unpopular with the military that on August 22 he was forced to resign not only this position but his role as Commander-in-Chief of the Army; he was replaced in the latter role by Pinochet. [9]

For some months now, the government had been afraid to call upon the national police known as the Carabineros, for fear of their lack of loyalty. In August 1973, a constitutional crisis was clearly in the offing: the Supreme Court publicly complained about the government's inability to enforce the law of the land and on August 22 the Chamber of Deputies (with the Christian Democrats now firmly uniting with the National Party) accused Allende's government of unconstitutional acts and called on the military ministers to assure the constitutional order. [10]

In early September 1973, Allende floated the idea of resolving the crisis with a plebiscite. His speech outlining such a solution was scheduled for September 12, but he was never able to deliver it.

On September 11, 1973, the Chilean military, led by General Pinochet and supported by the CIA, staged the Chilean coup of 1973 against Allende.

Just prior to the capture of the La Moneda (the Presidential Palace), with gunfire and explosions clearly audible in the background, Allende made what would become a famous farewell speech to Chileans on live radio, speaking of himself in the past tense, of his love for Chile and of his deep faith in its future. He stated that his commitment to Chile did not allow him to take an easy way out and be used as a propaganda tool by those he called "traitors" (accepting an offer of safe passage), clearly implying he intended to fight to the end.

Shortly afterwards, Allende was dead. At the time and for many years after, many of his supporters presumed that he was killed by the forces staging the coup. In recent years the view he committed suicide has become more accepted, particularly as testimonies of Dr. Patricio Guijón (a member of La Moneda's infirmary staff; not, as is sometimes reported, Allende's personal physician Dr. Enrique Paris Roa) and two close associates who were with him at the time of his death, confirmed the details of the suicide in news and documentary interviews.3 Also, members of Allende's immediate family including his wife, always outspoken, never disputed that it was a suicide.

It is known that the United States played a role in Chilean politics prior to the coup, but its degree of involvement in the coup itself is debated. The CIA was notified by its Chilean contacts of the impending coup two days in advance, but contends it "played no direct role in" the coup. [11]

After Pinochet assumed power, U.S. Secretary of State Henry Kissinger told U.S. President Richard Nixon that the U.S. "didn't do it" (referring to the coup itself) but had "created the conditions as great as possible" [12] , including leading economic sanctions. Recently declassified documents show that the United States government and the CIA had sought the overthrow of Allende in 1970, immediately before he took office ("Project FUBELT"), through the incident that claimed the life of then Commander-in-Chief, General René Schneider, but claims of their direct involvement in the 1973 coup are not proven by publicly available documentary evidence. Many potentially relevant documents still remain classified. See U.S. intervention in Chile.

Legacy and debate

More than thirty years after his death, Allende remains a controversial figure. Since his life ended before his presidential term was over, there has been much speculation as to what Chile would have been like had he been able to remain in power. However, one of his administration legacies is not subject to controversy in Chile, namely the nationalization of the copper mining industry. This was a major step toward Chile's development which not even Pinochet's administration would take back.

Allende's story is often cited in non-academic discussions about whether a Communist government has ever been democratically elected. While Allende legitimately won a democratic election, the significance of this has been disputed by some because he only had a plurality, not a majority, in the popular vote. This voting pattern is not uncommon in representative democracies, however; Bill Clinton, George W. Bush, Margaret Thatcher, Tony Blair, and even Nixon are among those leaders who have been elected without a majority of the popular vote.

Supporters' View

His supporters argue that he did not win an outright majority because Christian Democrat Radomiro Tomic, running on a leftist platform similar to Allende's, split the Left vote. Tomic and Allende together gathered 64% of the vote, a clear majority. Meanwhile, Allende's opponents maintain that Allende went much farther to the left than voters could have expected, and point out that the Christian Democratic Party later forged an alliance with the Right and was initially supportive of military intervention to remove Allende from office, although began to disassociate itself because of the manifestly undemocratic and violently repressive nature of the Pinochet Dictatorship.

Allende is seen as a hero to many on the political Left. Some view him as a martyr who died for the cause of socialism. His face has even been stylized and reproduced as a symbol of Marxism, similar to the famous images of Che Guevara. Some hold the United States, specifically Henry Kissinger and the CIA, responsible for his death, and view him as a victim of American imperialism. But for Allende's supporters, the most relevant and revolutionary of his legacies lies in his incorruptible democratic conviction, which nourished the idea that Socialism can be reached through a democratic, pacific path. It is argued that, under the light of history, this may raise him to a visionary, and the weight that his democratic ideas have in nowadays leftist Latin American politics can be felt in Venezuela and, most recently, Bolivia.

Opponents' View

Others view Allende much less favorably. He is criticized for his government's mass nationalization of private industry, alleged friendliness with more militant groups such as the Movement of the Revolutionary Left, and the supply shortages and hyperinflation that occurred during the latter years of his presidency; all these had combined to cause a strong polarization in the country and the committed opposition of the Christian Democratic Party at the time of the coup. He is also accused of having had an autocratic style, attempting to circumvent the Congress and having a hostile attitude toward critical media.

A common and more severe criticism is that because of his closeness with Fidel Castro and Eastern bloc countries, he was planning to convert Chile into a Cuban-style dictatorship. Such allegations are highly controversial. An outlandish example was offered by the military junta which overthrew Allende. It accused him of formulating the supposed "Plan Z", in which the Popular Unity government was accused to have planned a bloody coup of its own to install Allende as dictator. The junta alleged that the plot was to be no less than a blueprint for assassinations of military leaders and general "mass murder". Impartial observers have not been convinced by the assertion of a plot. One journalist noted that a striking feature of these allegations was that the documentation was “surprisingly deficient. . . Nothing is said about where the plan was discovered by military officers, no names or political organizations are directly linked to it and no strong evidence is presented to connect it to President Allende" (The New York Times 31 October 1973).

Accusations of racism

Recent controversy has surrounded Allende's 1933 doctoral dissertation "Mental Hygiene and Delinquency", the subject of a recent book Salvador Allende: Anti-Semitism and Euthanasia by Victor Farías, a Chilean-born teacher at the Latin America Institute of the Free University of Berlin. In his book, Farías claims that Allende held racist, homophobic and anti-semitic views, as well as believing at that time that mental illnesses, criminal behaviour, and alcoholism were hereditary. Farías allegations have been challenged by the Spanish President Allende Foundation, which published various relevant materials on the Internet in PDF form, including the dissertation itself and a letter of protest Allende and others sent to Adolf Hitler after Kristallnacht. [13] [14] The Foundation claims [15] that in his thesis Allende was merely quoting Italian-Jewish scientist Cesare Lombroso, whereas he himself was critical of these theories. Farías maintains the affirmations that appear in his book. The President Allende Foundation replied publishing the entire original text of Lombroso ["El Delito, sus causas y remedios", 1902, http://www.elclarin.cl/fpa/pdf/lombroso.pdf] and in April 2006 filed an anti-libel claim against Farias and his publisher in the Court of Justice of Madrid (Spain) [16].

Farías paraphrases of Lombroso have been much quoted; for example The Telegraph (UK) reported 12 May 2005 that "Allende… wrote: 'The Hebrews are characterised by certain types of crime: fraud, deceit, slander and above all usury. These facts permits the supposition that race plays a role in crime.' Among the Arabs, he wrote, were some industrious tribes but 'most are adventurers, thoughtless and lazy with a tendency to theft'. [17]

The Telegraph's quotation about the Jews appears to be a combination of two sentences that are not adjacent in the dissertation. Both are part of Allende's summary of Cesare Lombroso's views on different "tribes", "races" and "nations" being prone to different types of crime; the latter is misquoted. Allende's passage about the Jews reads "The Hebrews are characterized by certain types of crime: fraud, deceit, defamation and, above all, usury. On the other hand, murders and crimes of passion are the exception." After recounting Lombroso's views, Allende writes, "These data lead one to suspect that race influences crime. Nonetheless, we lack precise data to demonstrate this influence in the civilized world." The passage about Arabs is "Among the Arabs there are some honored and hardworking tribes, and others who are adventurers, thoughtless and lazy with a tendency to theft." There is no statement that the latter applies to "most" Arabs. [18]

Farías further claims to have found evidence that Allende had tried to implement his ideas about heredity during his period as Health Minister 1939-1941, and that he received help from German Nazis E. Brücher and Hans Betzhold in drafting of an unsuccessful bill mandating forced sterilisation of alcoholics. The President Allende Foundation has challenged Farias in the Court of Justice of Madrid (Spain)to prove that any bill on this issue has been proposed by Minister Allende to the Chilean Government or Parliament, and to prove as well Farías' allegation that Allende was bribed by the Nazi foreign minister Joachim von Ribbentrop without providing any evidence of it [19].

Surviving personal friends of Allende have completely rejected the validity of Victor Farías accusations of "racism" and "anti-semitism" for two major reasons: Allende's mother, Laura Gossens Uribe, was of Jewish descent and Allende considered himself a Marxist and socialist internationalist for most of his adult life.

Allende’s supposed “anti-semitism” is left unfounded not only because of Allende’s own Jewish ancestry which was well known in Chile but by the fact that it was often used by his political detractors against him. The renowned neo-nazi intellectual and former Chilean diplomat Miguel Serrano (who was the mentor to many in the fascist “Patria y Libertad” movement, which was instrumental in overseeing the CIA’s backed programme of destabilization in Chile) often spoke about Allende’s “Jewishness” or his “Judeo-Bolshevik” agenda.

During his term in office Allende - who was himself an atheist - supported a more ecumenical approach to national festivities and encouraged participation from the small Chilean Jewish community in celebrating Chile’s Independence Day, which had always been sanctified by the Roman Catholic Church. During his term in office the Great Rabbi of Santiago, spiritual leader of the Jewish Community, had a principal role in the preparation of an ecumenical service for this event.

Further countering accusations of anti-semitism is the fact that Allende entrusted two of the most important tasks of his government to Chilean Jews: Jacques Chonchol to direct and implemented the successful agrarian reform which completely transformed the country’s agricultural structure, and David Silberman Gurovich, who was in charge of consolidating the nationalization of the most important industry in the country, Codelco-Chuquicamata (the largest open-pit copper mine in the World).

In 1972, Salvador Allende suggested the Nazi hunter Simon Wiesenthal to ask the Chilean Supreme Court to extradite former SS Colonel Walther Rauff to Germany. The letters exchanged between Wiesental and President Allende are published in CLARIN [20].

Role in the Cold War

The nature of U.S. involvement in the coup that deposed Allende remains a heated debate topic in the context of U.S. conduct during the Cold War. While there were several coups in Latin America during this period, Allende's downfall remains one of the most controversial.

The KGB's archives record that Svyatoslav Kuznetsov, KGB case officer in Chile, was instructed by headquarters to "exert a favourable influence on Chilean government policy". The Times extract from the Mitrokhin Archive volume II from historian Christopher Andrew and KGB defector Vasili Mitrokhin says that "In the KGB's view, Allende's fundamental error was his unwillingness to use force against his opponents. Without establishing complete control over all the machinery of the State, his hold on power could not be secure." According to the KGB defector Allende received $30 000 from the Soviets for "solidifying trusted relations" and providing "valuable information" [21]. In 1972, Moscow downgraded its assessment of the prospects of the Allende regime. The "truckers' strike", backed by CIA funding, virtually paralysed the economy for three weeks, which Moscow saw as evidence of the weakness of the Popular Unity government.

Quotes

By Salvador Allende

- "The answer is the proletariat. If it wasn't so I wouldn't be here [...] As for the bourgeois state, at the present moment, we are seeking to overcome it. To overthrow it. [...] Our objective is total, scientific, Marxist socialism" — In an interview with French Journalist Regis Debray in 1970.

- (Attributed) "I am not the president of all the Chileans. I am not a hypocrite that says so." — At a public rally, quoted by all Chilean newspapers, January 17, 1971. President Allende sent a public letter to El Mercurio newspaper to deny this alleged statement.

- "¡Viva Chile! ¡Viva el pueblo! ¡Vivan los trabajadores!" ("Long live Chile! Long live the people! Long live the workers!") — last known words (in a radio broadcast on the morning of September 11, 1973)

- "I have been to Cuba many times. I have spoken many times with Fidel Castro and got to know Ernesto Guevara fairly well. I know of Cuba's struggle and its leaders. But the situation in Cuba is very different from that in Chile. Cuba came from a dictatorship; I arrived at the presidency after being senator for 25 years".[22] From the same interview: "I have some experience and I am putting it to use in a Chilean way, for the problems of Chile. ... We are not here to colonize anybody's minds."

About Salvador Allende

- "Allende is seeking the totality of power, which means Communist tyranny disguised as the dictatorship of the proletariat." — Statement from the National Assembly of the Chilean Christian Democratic party, May 15, 1973.

- "Of all of the leaders in the region, we considered Allende the most inimical to our interests. He was vocally pro-Castro and opposed to the United States. His internal policies were a threat to Chilean democratic liberties and human rights." — Henry Kissinger, Years of Renewal.

- "The Popular Unity government represented the first attempt anywhere to build a genuinely democratic transition to socialism — a socialism that, owing to its origins, might be guided not by authoritarian bureaucracy, but by democratic self-rule." — North American Congress on Latin America (NACLA) editorial, July 2003.

See also

|

|

Notes

1 Pronunciation (IPA):

/salƀaðoɽ aʝεnde/.

2 Biography of Allende from the official website of the Presidency of Chile. The current administration is headed by socialist Ricardo Lagos, a former Allende supporter. (See last paragraph)

3 Camus, Ignacio Gonzalez , El dia en que murio Allende ("The day that Allende Died"). Instituto Chileno de Estudios Humanísticos (ICHEH) and Centro de Estudios Sociales (CESOC), 1988. p. 282 and following.

External links and references

- Template:Es Official Government biography

- History of Chile under Salvador Allende and the Popular Unity by Ewin Martinez

- Template:Es Allende Memorial Site

- Hannah Cleaver Allende branded a fascist and anti-Semite 12 May 2005 in The Telegraph (UK).

- Template:Es Caso Pinochet. While nominally a page about the Pinochet case, this large collection of links includes Allende's dissertation and numerous documents (mostly PDFs) related to the dissertation and to the controversy about it, ranging from the Cesare Lombroso material discussed in Allende's dissertation to a collective telegram of protest over Kristallnacht signed by Allende.

- Template:Es Popular Unity of Salvador Allende

- Christopher Andrew and Vasili Mitrokhin, Mitrokhin archive: How 'weak' Allende was left out in the cold by the KGB describing relations between Allende and the KGB, including KGB payments to Allende. The Times September 19, 2005

- Template:Es Previously unreleased interview with Allende by Saul Landau in 1971, published by La Nacion on September 24th, 2005.

- Alternate source of the Resolution of August 22, 1973 (English, Spanish, French, German, Polish

- "Never Again: An essay about the breakdown of democracy in Chile" by José Piñera (examination of events leading up to, and implications regarding, the Resolution of August 22, 1973. (In English, Italian, Spanish) Mirror site