Neutron star

A neutron star is a type of compact star that can result from the gravitational collapse of a massive star after a supernova. Neutron stars are the densest and smallest stars known to exist in the Universe; with a radius of only about 11–11.5 km (7 miles), they can have a mass of about twice that of the Sun.

Neutron stars are composed almost entirely of neutrons, which are subatomic particles with no net electrical charge and with slightly larger mass than protons. Neutron stars are very hot and are supported against further collapse by quantum degeneracy pressure due to the phenomenon described by the Pauli exclusion principle, which states that no two neutrons (or any other fermionic particles) can occupy the same place and quantum state simultaneously.

A neutron star has a mass of at least 1.1 and perhaps up to 3 solar masses (M☉),[1][2] though the highest observed mass is 2.01 M☉. Neutron stars typically have a surface temperature around 6×105 K.[3][4][5][6][a] Neutron stars have overall densities of 3.7×1017 to 5.9×1017 kg/m3 (2.6×1014 to 4.1×1014 times the density of the Sun),[b] which is comparable to the approximate density of an atomic nucleus of 3×1017 kg/m3.[7] The neutron star's density varies from below 1×109 kg/m3 in the crust—increasing with depth—to above 6×1017 or 8×1017 kg/m3 deeper inside (denser than an atomic nucleus).[8] A normal-sized matchbox containing neutron-star material would have a mass of approximately 5 trillion tons or 1000 km3 of Earth rock.

In general, compact stars of less than 1.39 M☉ (the Chandrasekhar limit) are white dwarfs, whereas compact stars with a mass between 1.4 M☉ and 3 M☉ (the Tolman–Oppenheimer–Volkoff limit) should be neutron stars. The maximum observed mass of neutron stars is about 2 M☉. Compact stars with more than 10 M☉ will overcome the neutron degeneracy pressure and gravitational collapse will usually occur to produce a black hole, though the smallest observed mass of a stellar black hole is about 5 M☉.[9] Between 3 M☉ and 5 M☉, hypothetical intermediate-mass stars such as quark stars and electroweak stars have been proposed, but none have been shown to exist. The equations of state of matter at such high densities are not precisely known because of the theoretical and empirical difficulties (see quantum gravity).

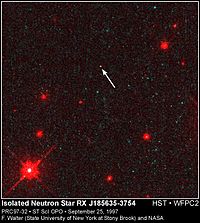

Some neutron stars rotate very rapidly (up to 716 times a second,[10][11] or approximately 43,000 revolutions per minute, giving a linear speed at the surface on the order of 0.165 c) and emit beams of electromagnetic radiation as pulsars. Indeed, the discovery of pulsars in 1967 first suggested that neutron stars exist. Gamma-ray bursts may be produced from rapidly rotating high-mass stars that collapse to form a neutron star, or from the merger of binary neutron stars. There are thought to be around 100 million neutron stars in the Milky Way, a figure obtained by estimating the number of stars that have gone supernova.[12] However, most are old and cold, and neutron stars can only be easily detected in certain instances, such as if they are a pulsar or part of a binary system. Non-rotating and non-accreting neutron stars are virtually undetectable; however, the Hubble Space Telescope has observed one thermally radiating neutron star, called RX J185635-3754.

Formation

Any main-sequence star with an initial mass of above 8 M☉ has the potential to become a neutron star. As the star evolves away from the main sequence, subsequent nuclear burning produces an iron-rich core. When all nuclear fuel in the core has been exhausted, the core must be supported by degeneracy pressure alone. Further deposits of material from shell burning cause the core to exceed the Chandrasekhar limit. Electron-degeneracy pressure is overcome and the core collapses further, sending temperatures soaring to over 5×109 K. At these temperatures, photodisintegration (the breaking up of iron nuclei into alpha particles by high-energy gamma rays) occurs. As the temperature climbs even higher, electrons and protons combine to form neutrons via electron capture, releasing a flood of neutrinos. When densities reach nuclear density of 4×1017 kg/m3, neutron degeneracy pressure halts the contraction. The infalling outer atmosphere of the star is flung outwards, becoming a Type II or Type Ib supernova. The remnant left is a neutron star. If it has a mass greater than about 5 M☉, it collapses further to become a black hole. Other neutron stars are formed within close binaries.

As the core of a massive star is compressed during a Type II, Type Ib or Type Ic supernova, and collapses into a neutron star, it retains most of its angular momentum. Because it has only a tiny fraction of its parent's radius (and therefore its moment of inertia is sharply reduced), a neutron star is formed with very high rotation speed, and then gradually slows down. Neutron stars are known that have rotation periods from about 1.4 ms to 30 s. The neutron star's density also gives it very high surface gravity, with typical values ranging from 1012 to 1013 m/s2 (more than 1011 times of that of Earth).[6] One measure of such immense gravity is the fact that neutron stars have an escape velocity ranging from 100,000 km/s to 150,000 km/s, that is, from a third to half the speed of light. Matter falling onto the surface of a neutron star would be accelerated to tremendous speed by the star's gravity. The force of impact would likely destroy the object's component atoms, rendering all its matter identical, in most respects, to the rest of the star.

Properties

The gravitational field at the star's surface is about 2×1011 times stronger than on Earth. Such a strong gravitational field acts as a gravitational lens and bends the radiation emitted by the star such that parts of the normally invisible rear surface become visible.[13] If the radius of the neutron star is or less, then the photons may be trapped in an orbit, thus making the whole surface of that neutron star visible, along with destabilizing orbits at that and less than that of the radius. A fraction of the mass of a star that collapses to form a neutron star is released in the supernova explosion from which it forms (from the law of mass-energy equivalence, E = mc2). The energy comes from the gravitational binding energy of a neutron star.

Because of the enormous gravity, time dilation between a neutron star and Earth is significant. While eight years could pass on the surface of a neutron star, a whole decade would have passed on Earth.[14]

Neutron star relativistic equations of state provided by Jim Lattimer include a graph of radius vs. mass for various models.[15] The most likely radii for a given neutron star mass are bracketed by models AP4 (smallest radius) and MS2 (largest radius). BE is the ratio of gravitational binding energy mass equivalent to observed neutron star gravitational mass of "M" kilograms with radius "R" meters,[16]

Given current values

and star masses "M" commonly reported as multiples of one solar mass,

then the relativistic fractional binding energy of a neutron star is

A 2 M☉ neutron star would not be more compact than 10,970 meters radius (AP4 model). Its mass fraction gravitational binding energy would then be 0.187, −18.7% (exothermic). This is not near 0.6/2 = 0.3, −30%.

A neutron star is so dense that one teaspoon (5 milliliters) of its material would have a mass over 5.5×1012 kg (that is 1100 tonnes per 1 nanolitre), about 900 times the mass of the Great Pyramid of Giza.[c] Hence, the gravitational force of a typical neutron star is such that if an object were to fall from a height of one meter, it would only take one microsecond to hit the surface of the neutron star, and would do so at around 2000 kilometers per second, or 7.2 million kilometers per hour.[18]

The temperature inside a newly formed neutron star is from around 1011 to 1012 kelvin.[8] However, the huge number of neutrinos it emits carry away so much energy that the temperature falls within a few years to around 106 kelvin.[8] Even at 1 million kelvin, most of the light generated by a neutron star is in X-rays.

The pressure increases from 3×1033 to 1.6×1035 Pa from the inner crust to the center.[19]

The equation of state for a neutron star is still not known. It is assumed that it differs significantly from that of a white dwarf, whose equation of state is that of a degenerate gas that can be described in close agreement with special relativity. However, with a neutron star the increased effects of general relativity can no longer be ignored. Several equations of state have been proposed (FPS, UU, APR, L, SLy, and others) and current research is still attempting to constrain the theories to make predictions of neutron star matter.[6][20] This means that the relation between density and mass is not fully known, and this causes uncertainties in radius estimates. For example, a 1.5 M☉ neutron star could have a radius of 10.7, 11.1, 12.1 or 15.1 kilometres (for EOS FPS, UU, APR or L respectively).[20]

Structure

Current understanding of the structure of neutron stars is defined by existing mathematical models, but it might be possible to infer through studies of neutron-star oscillations. Similar to asteroseismology for ordinary stars, the inner structure might be derived by analyzing observed frequency spectra of stellar oscillations.[6]

Current models indicate that matter at the surface of a neutron star is composed of ordinary atomic nuclei crushed into a solid lattice with a sea of electrons flowing through the gaps between them. It is possible that the nuclei at the surface are iron, due to iron's high binding energy per nucleon.[21] It is also possible that heavy elements, such as iron, simply sink beneath the surface, leaving only light nuclei like helium and hydrogen.[21] If the surface temperature exceeds 106 kelvin (as in the case of a young pulsar), the surface should be fluid instead of the solid phase observed in cooler neutron stars (temperature <106 kelvin).[21]

The "atmosphere" of the star is hypothesized to be at most several micrometers thick, and its dynamic is fully controlled by the star's magnetic field. Below the atmosphere one encounters a solid "crust". This crust is extremely hard and very smooth (with maximum surface irregularities of ~5 mm), because of the extreme gravitational field.[22] The expected hierarchy of phases of nuclear matter in the inner crust has been characterized as nuclear pasta.[23]

Proceeding inward, one encounters nuclei with ever increasing numbers of neutrons; such nuclei would decay quickly on Earth, but are kept stable by tremendous pressures. As this process continues at increasing depths, neutron drip becomes overwhelming, and the concentration of free neutrons increases rapidly. In this region, there are nuclei, free electrons, and free neutrons. The nuclei become increasingly small (gravity and pressure overwhelming the strong force) until the core is reached, by definition the point where they disappear altogether.

The composition of the superdense matter in the core remains uncertain. One model describes the core as superfluid neutron-degenerate matter (mostly neutrons, with some protons and electrons). More exotic forms of matter are possible, including degenerate strange matter (containing strange quarks in addition to up and down quarks), matter containing high-energy pions and kaons in addition to neutrons,[6] or ultra-dense quark-degenerate matter.

Rotation

Neutron stars rotate extremely rapidly after their formation due to the conservation of angular momentum; like spinning ice skaters pulling in their arms, the slow rotation of the original star's core speeds up as it shrinks. A newborn neutron star can rotate several times a second; sometimes, the neutron star absorbs orbiting matter from a companion star, increasing the rotation to several hundred times per second, reshaping the neutron star into an oblate spheroid.

Over time, neutron stars slow down (spin down) because their rotating magnetic fields radiate energy; older neutron stars may take several seconds for each revolution.

The rate at which a neutron star slows its rotation is usually constant and very small: the observed rates of decline are between 10−10 and 10−21 seconds for each rotation. Therefore, for a typical slow down rate of 10−15 seconds per rotation, a neutron star now rotating in 1 second will rotate in 1.000003 seconds after a century, or 1.03 seconds after 1 million years.

Sometimes a neutron star will spin up or undergo a glitch, a sudden small increase of its rotation speed. Glitches are thought to be the effect of a starquake — as the rotation of the star slows down, the shape becomes more spherical. Due to the stiffness of the "neutron" crust, this happens as discrete events when the crust ruptures, similar to tectonic earthquakes. After the starquake, the star will have a smaller equatorial radius, and because angular momentum is conserved, rotational speed increases. Recent work, however, suggests that a starquake would not release sufficient energy for a neutron star glitch; it has been suggested that glitches may instead be caused by transitions of vortices in the superfluid core of the star from one metastable energy state to a lower one.[24]

Neutron stars have been observed to "pulse" radio and x-ray emissions believed to be caused by particle acceleration near the magnetic poles, which need not be aligned with the rotation axis of the star. Through mechanisms not yet entirely understood, these particles produce coherent beams of radio emission. External viewers see these beams as pulses of radiation whenever the magnetic pole sweeps past the line of sight. The pulses come at the same rate as the rotation of the neutron star, and thus, appear periodic. Neutron stars that emit such pulses are called pulsars.

The most rapidly rotating neutron star currently known, PSR J1748-2446ad, rotates at 716 rotations per second.[25] A recent paper reported the detection of an X-ray burst oscillation (an indirect measure of spin) at 1122 Hz from the neutron star XTE J1739-285.[26] However, at present, this signal has only been seen once, and should be regarded as tentative until confirmed in another burst from this star.

Neutron star collision and nucleosynthesis

It has been suggested that Gold and other heavy elements are created from the collision of neutron stars

History of discoveries

In 1934, Walter Baade and Fritz Zwicky proposed the existence of the neutron star,[27][d] only a year after the discovery of the neutron by Sir James Chadwick.[30] In seeking an explanation for the origin of a supernova, they tentatively proposed that in supernova explosions ordinary stars are turned into stars that consist of extremely closely packed neutrons that they called neutron stars. Baade and Zwicky correctly proposed at that time that the release of the gravitational binding energy of the neutron stars powers the supernova: "In the supernova process, mass in bulk is annihilated". Neutron stars were thought to be too faint to be detectable and little work was done on them until November 1967, when Franco Pacini (1939–2012) pointed out that if the neutron stars were spinning and had large magnetic fields, then electromagnetic waves would be emitted. Unbeknown to him, radio astronomer Antony Hewish and his research assistant Jocelyn Bell at Cambridge were shortly to detect radio pulses from stars that are now believed to be highly magnetized, rapidly spinning neutron stars, known as pulsars.

In 1965, Antony Hewish and Samuel Okoye discovered "an unusual source of high radio brightness temperature in the Crab Nebula".[31] This source turned out to be the Crab Pulsar that resulted from the great supernova of 1054.

In 1967, Iosif Shklovsky examined the X-ray and optical observations of Scorpius X-1 and correctly concluded that the radiation comes from a neutron star at the stage of accretion.[32]

In 1967, Jocelyn Bell and Antony Hewish discovered regular radio pulses from CP 1919. This pulsar was later interpreted as an isolated, rotating neutron star. The energy source of the pulsar is the rotational energy of the neutron star. The majority of known neutron stars (about 2000, as of 2010) have been discovered as pulsars, emitting regular radio pulses.

In 1971, Riccardo Giacconi, Herbert Gursky, Ed Kellogg, R. Levinson, E. Schreier, and H. Tananbaum discovered 4.8 second pulsations in an X-ray source in the constellation Centaurus, Cen X-3. They interpreted this as resulting from a rotating hot neutron star. The energy source is gravitational and results from a rain of gas falling onto the surface of the neutron star from a companion star or the interstellar medium.

In 1974, Antony Hewish was awarded the Nobel Prize in Physics "for his decisive role in the discovery of pulsars" without Jocelyn Bell who shared in the discovery.

In 1974, Joseph Taylor and Russell Hulse discovered the first binary pulsar, PSR B1913+16, which consists of two neutron stars (one seen as a pulsar) orbiting around their center of mass. Einstein's general theory of relativity predicts that massive objects in short binary orbits should emit gravitational waves, and thus that their orbit should decay with time. This was indeed observed, precisely as general relativity predicts, and in 1993, Taylor and Hulse were awarded the Nobel Prize in Physics for this discovery.

In 1982, Don Backer and colleagues discovered the first millisecond pulsar, PSR B1937+21. This objects spins 642 times per second, a value that placed fundamental constraints on the mass and radius of neutron stars. Many millisecond pulsars were later discovered, but PSR B1937+21 remained the fastest-spinning known pulsar for 24 years, until PSR J1748-2446ad (which spins more than 700 times a second) was discovered.

In 2003, Marta Burgay and colleagues discovered the first double neutron star system where both components are detectable as pulsars, PSR J0737-3039. The discovery of this system allows a total of 5 different tests of general relativity, some of these with unprecedented precision.

In 2010, Paul Demorest and colleagues measured the mass of the millisecond pulsar PSR J1614–2230 to be 1.97±0.04 M☉, using Shapiro delay.[33] This was substantially higher than any previously measured neutron star mass (1.67 M☉, see PSR J1903+0327), and places strong constraints on the interior composition of neutron stars.

In 2013, John Antoniadis and colleagues measured the mass of PSR J0348+0432 to be 2.01±0.04 M☉, using white dwarf spectroscopy.[34] This confirmed the existence of such massive stars using a different method. Furthermore, this allowed, for the first time, a test of general relativity using such a massive neutron star.

Population and distances

At present, there are about 2000 known neutron stars in the Milky Way and the Magellanic Clouds, the majority of which have been detected as radio pulsars. Neutron stars are mostly concentrated along the disk of the Milky Way although the spread perpendicular to the disk is large because the supernova explosion process can impart high speeds (400 km/s) to the newly formed neutron star.

Some of the closest neutron stars are RX J1856.5-3754 about 400 light years away and PSR J0108-1431 at about 424 light years.[35] RX J1856.5-3754 is a member of a close group of neutron stars called The Magnificent Seven. Another nearby neutron star that was detected transiting the backdrop of the constellation Ursa Minor has been nicknamed Calvera by its Canadian and American discoverers, after the villain in the 1960 film The Magnificent Seven. This rapidly moving object was discovered using the ROSAT/Bright Source Catalog.

Binary neutron star systems

About 5% of all known neutron stars are members of a binary system. The formation and evolution scenario of binary neutron stars is a rather exotic and complicated process.[36] The companion stars may be either ordinary stars, white dwarfs or other neutron stars. According to modern theories of binary evolution it is expected that neutron stars also exist in binary systems with black hole companions. Such binaries are expected to be prime sources for emitting gravitational waves. Neutron stars in binary systems often emit X-rays, which is caused by the heating of material (gas) accreted from the companion star. Material from the outer layers of a (bloated) companion star is sucked towards the neutron star as a result of its very strong gravitational field. As a result of this process binary neutron stars may also coalesce into black holes if the accretion of mass takes place under extreme conditions.[37] It has been proposed that coalescence of binaries consisting of two neutron stars may be responsible for producing short gamma-ray bursts. Such events may also be responsible for producing all chemical elements beyond iron,[38] as opposed to the supernova nucleosynthesis theory.

Subtypes

- Neutron star

- Protoneutron star (PNS), theorized.[39]

- Radio-quiet neutron stars

- Radio loud neutron star

- Single pulsars–general term for neutron stars that emit directed pulses of radiation towards us at regular intervals (due to their strong magnetic fields).

- Rotation-powered pulsar ("radio pulsar")

- Magnetar–a neutron star with an extremely strong magnetic field (1000 times more than a regular neutron star), and long rotation periods (5 to 12 seconds).

- Soft gamma repeater (SGR)

- Anomalous X-ray pulsar (AXP)

- Magnetar–a neutron star with an extremely strong magnetic field (1000 times more than a regular neutron star), and long rotation periods (5 to 12 seconds).

- Rotation-powered pulsar ("radio pulsar")

- Binary pulsars

- Low-mass X-ray binaries (LMXB)

- Intermediate-mass X-ray binaries (IMXB)

- High-mass X-ray binaries (HMXB)

- Accretion-powered pulsar ("X-ray pulsar")

- X-ray burster–a neutron star with a low mass binary companion from which matter is accreted resulting in irregular bursts of energy from the surface of the neutron star.

- Millisecond pulsar (MSP) ("recycled pulsar")

- Sub-millisecond pulsar[40]

- Single pulsars–general term for neutron stars that emit directed pulses of radiation towards us at regular intervals (due to their strong magnetic fields).

- Exotic star

- Quark star–currently a hypothetical type of neutron star composed of quark matter, or strange matter. As of 2008, there are three candidates.

- Electroweak star–currently a hypothetical type of extremely heavy neutron star, in which the quarks are converted to leptons through the electroweak force, but the gravitational collapse of the star is prevented by radiation pressure. As of 2010, there is no evidence for their existence.

- Preon star–currently a hypothetical type of neutron star composed of preon matter. As of 2008, there is no evidence for the existence of preons.

Giant nucleus

A neutron star has some of the properties of an atomic nucleus, including density (within an order of magnitude) and being composed of nucleons. In popular scientific writing, neutron stars are therefore sometimes described as giant nuclei. However, in other respects, neutron stars and atomic nuclei are quite different. In particular, a nucleus is held together by the strong interaction, whereas a neutron star is held together by gravity, and thus the density and structure of neutron stars is more variable. It is generally more useful to consider such objects as stars.

Examples of neutron stars

- PSR J0108-1431 – closest neutron star

- LGM-1 – the first recognized radio-pulsar

- PSR B1257+12 – the first neutron star discovered with planets (a millisecond pulsar)

- SWIFT J1756.9-2508 – a millisecond pulsar with a stellar-type companion with planetary range mass (below brown dwarf)

- PSR B1509-58 source of the "Hand of God" photo shot by the Chandra X-ray Observatory.

- PSR J0348+0432 – the most massive neutron star with a well-constrained mass, .

Gallery

-

Video - Neutron stars contain 500,000 Earth-masses in 25 km (16 mi) dia. sphere.

-

Video - Neutron stars colliding (animation).

-

Video - Neutron star collision.

See also

Notes

- ^ A neutron star's density increases as its mass increases, and its radius decreases non-linearly. (archived image: NASA mass radius graph) A newer page is here: "RXTE Discovers Kilohertz Quasiperiodic Oscillations". NASA. Retrieved 17 February 2016. (specifically the image [1])

- ^ 3.7×1017 kg/m3 derives from mass 2.68 × 1030 kg / volume of star of radius 12 km; 5.9×1017 kg m−3 derives from mass 4.2×1030 kg per volume of star radius 11.9 km

- ^ The average density of material in a neutron star of radius 10 km is 1.1×1012 kg cm−3. Therefore, 5 ml of such material is 5.5×1012 kg, or 5 500 000 000 metric tons. This is about 15 times the total mass of the human world population. Alternatively, 5 ml from a neutron star of radius 20 km radius (average density 8.35×1010 kg cm−3) has a mass of about 400 million metric tons, or about the mass of all humans.

- ^ Even before the discovery of neutron, in 1931, neutron stars were anticipated by Lev Landau, who wrote about stars where "atomic nuclei come in close contact, forming one gigantic nucleus"[28]). However, the widespread opinion that Landau predicted neutron stars proves to be wrong.[29]

References

- ^ Özel, Feryal; Psaltis, Dimitrios; Narayan, Ramesh; Santos Villarreal, Antonio (September 2012). "On the Mass Distribution and Birth Masses of Neutron Stars". The Astrophysical Journal. 757 (1): 13. arXiv:1201.1006. Bibcode:2012ApJ...757...55O. doi:10.1088/0004-637X/757/1/55. Retrieved 14 May 2015.

- ^ Chamel, N.; Haensel, P.; Zdunik, J.L.; Fantina, A.F. (19 November 2013). "On the Maximum Mass of Neutron Stars" (PDF). International Journal of Modern Physics. 1 (28): 1330018. arXiv:1307.3995. Bibcode:2013IJMPE..2230018C. doi:10.1142/S021830131330018X. Retrieved 14 May 2015.

- ^ Bulent Kiziltan (2011). Reassessing the Fundamentals: On the Evolution, Ages and Masses of Neutron Stars. Universal-Publishers. ISBN 1-61233-765-1.

- ^ Neutron star mass measurements

- ^ "Nasa Ask an Astrophysist: Maximum Mass of a Neutron Star".

- ^ a b c d e Paweł Haensel; A Y Potekhin; D G Yakovlev (2007). Neutron Stars. Springer. ISBN 0-387-33543-9.

- ^ "Calculating a Neutron Star's Density". Retrieved 2006-03-11. NB 3 × 1017 kg/m3 is 3×1014 g/cm3

- ^ a b c "Introduction to neutron stars". Retrieved 2007-11-11.

- ^ [2], a 10 M☉ star will collapse into a black hole.

- ^ Hessels, Jason; Ransom, Scott M.; Stairs, Ingrid H.; Freire, Paulo C. C.; et al. (2006). "A Radio Pulsar Spinning at 716 Hz". Science. 311 (5769): 1901–1904. arXiv:astro-ph/0601337. Bibcode:2006Sci...311.1901H. doi:10.1126/science.1123430. PMID 16410486.

- ^ Naeye, Robert (2006-01-13). "Spinning Pulsar Smashes Record". Sky & Telescope. Retrieved 2008-01-18.

- ^ Camenzind, Max (24 Feb 2007). Compact Objects in Astrophysics: White Dwarfs, Neutron Stars and Black Holes. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 269. ISBN 978-3-540-49912-1.

- ^ a b c Zahn, Corvin (1990-10-09). "Tempolimit Lichtgeschwindigkeit" (in German). Retrieved 2009-10-09.

Durch die gravitative Lichtablenkung ist mehr als die Hälfte der Oberfläche sichtbar. Masse des Neutronensterns: 1, Radius des Neutronensterns: 4, ... dimensionslosen Einheiten (c, G = 1)

- ^ Black Hole: How an Idea Abandoned by Newtonians, Hated by Einstein, and Gambled On by Hawking Became Loved

- ^ Neutron Star Masses and Radii, p. 9/20, bottom

- ^ J. M. Lattimer and M. Prakash, "Neutron Star Structure and the Equation of State" Astrophysical J. 550(1) 426 (2001); http://arxiv.org/abs/astro-ph/0002232

- ^ Measurement of Newton's Constant Using a Torsion Balance with Angular Acceleration Feedback , Phys. Rev. Lett. 85(14) 2869 (2000)

- ^ Miscellaneous Facts

- ^ Neutron degeneracy pressure (Archive). Physics Forums. Retrieved on 2011-10-09.

- ^ a b NASA. Neutron Star Equation of State Science Retrieved 2011-09-26 Template:Wayback

- ^ a b c V. S. Beskin (1999). "Radiopulsars". УФН. T.169, №11, p.1173-1174

- ^ neutron star

- ^ Pons, José A.; Viganò, Daniele; Rea, Nanda (2013). "Too much "pasta" for pulsars to spin down". Nature Physics. 9 (7): 431–434. arXiv:1304.6546. Bibcode:2013NatPh...9..431P. doi:10.1038/nphys2640.

- ^ Alpar, M Ali (January 1, 1998). "Pulsars, glitches and superfluids". Physicsworld.com.

- ^ [astro-ph/0601337] A Radio Pulsar Spinning at 716 Hz

- ^ University of Chicago Press – Millisecond Variability from XTE J1739285 – 10.1086/513270

- ^ Baade, Walter; Zwicky, Fritz (1934). "Remarks on Super-Novae and Cosmic Rays". Phys. Rev. 46 (1): 76–77. Bibcode:1934PhRv...46...76B. doi:10.1103/PhysRev.46.76.2.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|last-author-amp=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - ^ Landau L.D. (1932). "On the theory of stars". Phys. Z. Sowjetunion. 1: 285–288.

- ^ P. Haensel, A. Y. Potekhin, & D. G. Yakovlev (2007). Neutron Stars 1: Equation of State and Structure (New York: Springer), page 2 http://adsabs.harvard.edu/abs/2007ASSL..326.....H

- ^ Chadwick, James (1932). "On the possible existence of a neutron". Nature. 129 (3252): 312. Bibcode:1932Natur.129Q.312C. doi:10.1038/129312a0.

- ^ Hewish, A.; Okoye, S. E. (1965). "Evidence of an unusual source of high radio brightness temperature in the Crab Nebula". Nature. 207 (4992): 59–60. Bibcode:1965Natur.207...59H. doi:10.1038/207059a0.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|last-author-amp=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - ^ Shklovsky, I.S. (April 1967). "On the Nature of the Source of X-Ray Emission of SCO XR-1". Astrophys. J. 148 (1): L1–L4. Bibcode:1967ApJ...148L...1S. doi:10.1086/180001.

- ^ Demorest, PB; Pennucci, T; Ransom, SM; Roberts, MS; et al. (2010). "A two-solar-mass neutron star measured using Shapiro delay". Nature. 467 (7319): 1081–1083. arXiv:1010.5788. Bibcode:2010Natur.467.1081D. doi:10.1038/nature09466. PMID 20981094.

- ^ Antoniadis, J (2012). "A Massive Pulsar in a Compact Relativistic Binary". Science. 340 (6131): 1233232. arXiv:1304.6875. Bibcode:2013Sci...340..448A2010. doi:10.1126/science.1233232.

{{cite journal}}: Check|bibcode=length (help) - ^ Posselt, B.; Neuhäuser, R.; Haberl, F. (March 2009). "Searching for substellar companions of young isolated neutron stars". Astronomy and Astrophysics. 496 (2): 533–545. arXiv:0811.0398. Bibcode:2009A&A...496..533P. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/200810156.

- ^ Tauris & van den Heuvel (2006), in Compact Stellar X-ray Sources. Eds. Lewin and van der Klis, Cambridge University Press http://adsabs.harvard.edu/abs/2006csxs.book..623T

- ^ Compact Stellar X-ray Sources (2006). Eds. Lewin and van der Klis, Cambridge University

- ^ Urry, Meg (July 20, 2013). "Gold comes from stars". CNN.

- ^ Neutrino-Driven Protoneutron Star Winds, Todd A. Thompson.

- ^ Nakamura, T. (1989). "Binary Sub-Millisecond Pulsar and Rotating Core Collapse Model for SN1987A". Progress of Theoretical Physics. 81 (5): 1006–1020. Bibcode:1989PThPh..81.1006N. doi:10.1143/PTP.81.1006.

- "ASTROPHYSICS: ON OBSERVED PULSARS". scienceweek.com. Retrieved 6 August 2004.

- Norman K. Glendenning; R. Kippenhahn; I. Appenzeller; G. Borner; et al. (2000). Compact Stars (2nd ed.).

- Kaaret; Prieskorn; in 't Zand; Brandt; et al. (2006). "Evidence for 1122 Hz X-Ray Burst Oscillations from the Neutron-Star X-Ray Transient XTE J1739-285". The Astrophysical Journal. 657 (2): L97. arXiv:astro-ph/0611716. Bibcode:2007ApJ...657L..97K. doi:10.1086/513270.

External links

- Introduction to neutron stars

- Neutron Stars for Undergraduates and its Errata

- NASA on pulsars

- "NASA Sees Hidden Structure Of Neutron Star In Starquake". SpaceDaily.com. April 26, 2006

- "Mysterious X-ray sources may be lone neutron stars". New Scientist.

- "Massive neutron star rules out exotic matter". New Scientist. According to a new analysis, exotic states of matter such as free quarks or BECs do not arise inside neutron stars.

- "Neutron star clocked at mind-boggling velocity". New Scientist. A neutron star has been clocked traveling at more than 1500 kilometers per second.