General relativity

General relativity (GR) is the geometrical theory of gravitation published by Albert Einstein in 1915. It unifies special relativity and Isaac Newton's law of universal gravitation with the insight that gravitation is not due to a force but rather is a manifestation of curved space and time, this curvature being produced by the mass-energy and momentum content of the spacetime. General relativity is distinguished from other metric theories of gravitation by its use of the Einstein field equations to relate spacetime content and spacetime curvature.

Overview

Treatment of gravitation

In this theory, spacetime is treated as a 4-dimensional Lorentzian manifold which is curved by the presence of mass, energy, and momentum (or stress-energy) within it. The relationship between stress-energy and the curvature of spacetime is described by the Einstein field equations. The motion of objects being influenced solely by the geometry of spacetime (inertial motion) occurs along special paths called timelike and null geodesics of spacetime.

Justification

The justification for creating general relativity comes from the equivalence principle, which dictates that freefalling observers are the ones in inertial motion. A consequence of this insight is that inertial observers can accelerate with respect to each other. (Think of two balls falling on opposite sides of the Earth, for example.) This redefinition is incompatible with Newton's first law of motion, and cannot be accounted for in the Euclidean geometry of special relativity. To quote Einstein himself:

- "If all accelerated systems are equivalent, then Euclidean geometry cannot hold in all of them." [1]

Thus the equivalence principle led Einstein to search for a gravitational theory which involves curved spacetimes.

Another motivating factor was the realization that relativity calls for gravitation to be expressed as a rank-two tensor, and not just a vector as was the case in Newtonian physics [2]. (An analogy is the electromagnetic field tensor of special relativity). Thus Einstein sought a rank-two tensor means of describing curved spacetimes surrounding massive objects. This effort came to fruition with the discovery of the Einstein field equations in 1915.

Fundamental principles

General relativity is based on a set of fundamental principles which guided its development. These are:

- The general principle of relativity: The laws of physics must be the same for all observers (accelerated or not).

- The principle of general covariance: The laws of physics must take the same form in all coordinate systems.

- The principle that inertial motion is geodesic motion: The world lines of particles unaffected by physical forces are timelike or null geodesics of spacetime.

- The principle of local Lorentz invariance: The laws of special relativity apply locally for all inertial observers.

- Spacetime is curved: This permits gravitational effects such as freefall to be described as a form of inertial motion. (See the discussion below of a person standing on Earth, under "Coordinate vs. physical acceleration.")

- Spacetime curvature is created by stress-energy within the spacetime: This is described in general relativity by the Einstein field equations.

(The equivalence principle, which was the starting point for the development of general relativity, ended up being a consequence of the general principle of relativity and the principle that inertial motion is geodesic motion.)

Spacetime as a curved Lorentzian manifold

In general relativity, the spacetime concept introduced by Hermann Minkowski for special relativity is modified. More specifically, general relativity stipulates that spacetime is:

- curved: Spacetime has a non-Euclidean geometry. In special relativity, spacetime is flat.

- Lorentzian: The metrics of spacetime must have a mixed metric signature. This is inherited from special relativity.

- four dimensional: to cover the three spatial dimensions and time. This is also inherited from special relativity.

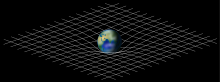

The curvature of spacetime (caused by the presence of stress-energy) can be viewed intuitively in the following way. Placing a heavy object such as a bowling ball on a trampoline will produce a 'dent' in the trampoline. This is analogous to a large mass such as the Earth causing the local spacetime geometry to curve. This is represented by the image at the top of this article. The larger the mass, the bigger the amount of curvature. A relatively light object placed in the vicinity of the 'dent', such as a ping-pong ball, will accelerate towards the bowling ball in a manner governed by the 'dent'. Firing the ping-pong ball at just the right speed towards the 'dent' will result in the ping-pong ball 'orbiting' the bowling ball. This is analogous to the Moon orbiting the Earth, for example.

Similarly, in general relativity massive objects do not directly impart a force on other massive objects as hypothesized in Newton's action at a distance idea. Instead (in a manner analogous to the ping-pong ball's response to the bowling ball's dent rather than the bowling ball itself), other massive objects respond to how the first massive object curves spacetime.

The mathematics of general relativity

Due to the expectation that spacetime is curved, Riemannian geometry (a type of non-Euclidean geometry) must be used. In essence, spacetime does not adhere to the "common sense" rules of Euclidean geometry, but instead objects that were initially traveling in parallel paths through spacetime (meaning that their velocities do not differ to first order in their separation) come to travel in a non-parallel fashion. This effect is called geodesic deviation, and it is used in general relativity as an alternative to gravity. For example, two people on the Earth heading due north from different positions on the equator are initially traveling on parallel paths, yet at the north pole those paths will cross. Similarly, two balls initially at rest with respect to and above the surface of the Earth (which are parallel paths by virtue of being at rest with respect to each other) come to have a converging component of relative velocity as both accelerate towards the center of the Earth due to their subsequent freefall. (Another way of looking at this is how a single ball moving in a purely timelike fashion parallel to the center of the Earth comes through geodesic motion to be moving towards the center of the Earth.)

The requirements of the mathematics of general relativity are further modified by the other principles. Local Lorentz Invariance requires that the manifolds described in GR be 4-dimensional and Lorentzian instead of Riemannian. In addition, the principle of general covariance forces that math to be expressed using tensor calculus. Tensor calculus permits a manifold as mapped with a coordinate system to be equipped with a metric tensor of spacetime which describes the incremental (spacetime) intervals between coordinates from which both the geodesic equations of motion and the curvature tensor of the spacetime can be ascertained.

The Hilbert-Einstein field equations

The Einstein field equations (EFE) describe how stress-energy causes curvature of spacetime and are usually written in tensor form (using abstract index notation) as

where is the Einstein tensor, is the stress-energy tensor and is a constant. The tensors and are both rank 2 symmetric tensors, that is, they can each be thought of as 4×4 matrices, each of which contains 10 independent terms.

An alternative form of the Einstein field equations includes a Cosmological Constant, .

where is the cosmological constant and is the spacetime metric. Einstein originally introduced the cosmological term to allow a flat spacetime solution to his field equations. However, later, after seeing Edwin Hubble's evidence for an expanding universe, he regretted adding the term, calling it the "biggest blunder" of his life. For many years the cosmological constant was almost universally considered to be 0. The cosmological term, however, is still interesting today as current cosmological studies indicate that the expansion of the universe may be accelerating.

The solutions of the EFE are metrics of spacetime. These metrics describe the structure of spacetime given the stress-energy and coordinate mapping used to obtain that solution. Being non-linear differential equations, the EFE often defy attempts to obtain an exact solution; however, many such solutions are known.

The EFE reduce to Newton's law of gravity in the limiting cases of a weak gravitational field and slow speed relative to the speed of light. In fact, the value of in the EFE is determined to be by making these two approximations.

The EFE are the identifying feature of general relativity. Other theories built out of the same premises include additional rules and/or constraints. The result almost invariably is a theory with different field equations (such as Brans-Dicke theory, teleparallelism, Rosen's bimetric theory, and Einstein-Cartan theory).

Coordinate vs. physical acceleration

One of the greatest sources of confusion about general relativity comes from the need to distinguish between coordinate and physical accelerations.

In classical mechanics, space is preferentially mapped with a Cartesian coordinate system. Inertial motion then occurs as one moves through this space at a consistent coordinate rate with respect to time. Any change in this rate of progression must be due to a force, and therefore a physical and coordinate acceleration were in classical mechanics one and the same. It is important to note that in special relativity that same kind of Cartesian coordinate system was used, with time being added as a fourth dimension and defined for an observer using the Einstein synchronization procedure. As a result, physical and coordinate acceleration correspond in special relativity too, although their magnitudes may vary.

In general relativity, the elegance of a flat spacetime and the ability to use a preferred coordinate system are lost (due to stress-energy curving spacetime and the principle of general covariance). Consequently, coordinate and physical accelerations become sundered. For example: Try using a radial coordinate system in classical mechanics. In this system, an inertially moving object which passes by (instead of through) the origin point is found to first be moving mostly inwards, then to be moving tangentially with respect to the origin, and finally to be moving outwards, yet is moving in a straight line. This is an example of an inertially moving object undergoing a coordinate acceleration, and the way this coordinate acceleration changes as the object travels is given by the geodesic equations for the manifold and coordinate system in use..

Another more direct example is the case of someone standing on the Earth, where they are at rest with respect to the surface coordinates for the Earth (latitude, longitude, and elevation) but are undergoing a continuous physical acceleration because the mechanical resistance of the Earth's surface keeps them from free falling.

Predictions of general relativity

- (For more detailed information about tests and predictions of general relativity, see tests of general relativity).

Gravitational effects

Acceleration effects

These effects occur in any accelerated frame of reference, and are therefore independent of the curvature of spacetime. (Note however that spacetime curvature usually is the source of the causative acceleration when these effects are being observed.)

- Gravitational redshifting of light: The frequency of light will decrease (shifting visible light towards the red end of the spectrum) as it moves to higher gravitational potentials (out of a gravity well). Confirmed by the Pound-Rebka experiment.

- Gravitational time dilation: Clocks will run slower at lower gravitational potentials (deeper within a gravity well). Confirmed by the Haefele-Keating experiment and GPS.

- Shapiro effect (also known as gravitational time delay): Signals will take longer than expected to move through a gravitational field. Confirmed through observations of signals from spacecraft and pulsars passing behind the Sun as seen from the Earth.

Bending of light

This bending also occurs in any accelerated frame of reference. However, the details of the bending and therefore the gravitational lensing effects are governed by spacetime curvature.

- The magnitude of this effect is twice the Newtonian prediction. It was confirmed by astronomical observations during eclipses of the Sun and observations of pulsars passing behind the Sun.

- Gravitational lensing: One distant object in front of or close to being in front of another much more distant object can change how the more distant object is seen. These effects include

- Multiple views of the same object: Observations of quasars whose light passes close to an intervening galaxy.

- Brightening of a star due to the focusing effects of a planet or another star passing in front of it: Such "microlensing" events are now regularly observed.

- Einstein rings and arcs: One object directly behind another can make the more distant object's light appear as a ring. When almost directly behind, the result is an arc. Observed for distant galaxies.

Orbital effects

These are ways in which the celestial mechanics of general relativity differs from that of classical mechanics.

- Non-Newtonian periapsis precession: The apsides of orbits precess more than expected under Newton's theory of gravity. This has been confirmed for Mercury and observed in several binary pulsars.

- Orbital decay due to the emission of gravitational radiation: This has been observed in binary pulsars.

- Geodetic precession: Because of the curvature of spacetime, the orientation of an orbiting gyroscope will change over time. This is being tested by Gravity Probe B.

Rotational effects

These involve the behavior of spacetime around a rotating massive object.

- Frame dragging: A rotating object will drag the spacetime along with it. This will cause the orientation of a gyroscope to change over time. For a spacecraft in a polar orbit, the direction of this effect is perpendicular to the geodetic precession mentioned above. This prediction is also being tested by Gravity Probe B.

Black holes

Black holes are objects which have gravitationally collapsed behind an event horizon. In a "classical" black hole, nothing that enters can ever escape. The disappearance of light and matter within a black hole may be thought of as their entering a region where all null and timelike geodesic paths are warped so that they point inwards. Stephen Hawking has shown that black holes can "leak" mass, a phenomenon called Hawking radiation, a quantum effect not in violation of Einstein's theory.

Cosmological effects

- Expansion of the universe: This is predicted by cosmological solutions of the Einstein Field Equations. Its existence was confirmed by Edwin Hubble in 1929.

- Cosmological redshift: Light from distant galaxies will be redshifted due to their movement away from the observer according to Hubble's law.

- Big Bang: The arising of the universe from a primordial singularity.

- Cosmic microwave background radiation: The remnants of the primordial fireball. Discovered by Arno Penzias and Robert Wilson in 1965.

- Dark energy: This is an energy field of unknown composition that may exist throughout the universe. Recent observations of distant supernovae indicate that the expansion of the universe is currently "accelerating". The solutions of the Einstein field equations that call for this behavior for the current universe, which may require the reintroduction of the cosmological constant, are for a stress-energy which is at least 70% dark energy.

Other predictions

- The equivalence of inertial mass and gravitational mass: This follows naturally from freefall being inertial motion.

- The strong equivalence principle: Even a self-gravitating object will respond to an external gravitational field in the same manner as a test particle would. (This is often violated by alternative theories.)

- Gravitational radiation: Orbiting objects and merging neutron stars and/or black holes are expected to emit gravitational radiation.

- Orbital decay (described above).

- Binary pulsar mergers: May create gravitational waves strong enough to be observed here on Earth. Several gravitational wave observatories are (or will soon be) in operation. However, there are no confirmed observations of gravitational radiation at this time.

- Gravitons: According to quantum mechanics, gravitational radiation must be composed of quanta called gravitons. General relativity predicts that these will be spin-2 particles. They have not been observed.

- Only quadrupole (and higher order multipole) moments create gravitational radiation.

- Dipole gravitational radiation (prohibited by this prediction) is predicted by some alternative theories. It has not been observed.

Relationship to other physical theories

Classical mechanics and special relativity

Classical mechanics and special relativity are lumped together here because special relativity is in many ways intermediate between general relativity and classical mechanics, and shares many attributes with classical mechanics.

Note that in the discussion which follows, the mathematics of general relativity is used heavily. Also note that under the principle of minimal coupling, the physical equations of special relativity can be turned into their general relativity equivalent by replacing the Minkowski metric (ηab) with the relevant metric of spacetime (gab) and by replacing any regular derivatives with covariant derivatives. In the discussions that follow, the change of metrics is implied.

Inertia

In both classical mechanics and special relativity, space and then spacetime were assumed to be flat. In the language of tensor calculus, this meant that Rabcd = 0, where Rabcd is the Riemann curvature tensor. In addition, the coordinate system itself was also assumed to be Cartesian. These restrictions permit inertial motion to be described mathematically as

where

- xa is a position vector,

- , and

- τ is proper time.

Note that in classical mechanics, xa is three-dimensional and τ ≡ t, where t is coordinate time.

In general relativity, these restrictions on the shape of spacetime and on the coordinate system to be used are lost. Therefore a different definition of inertial motion is required. In relativity, inertial motion occurs along timelike or null geodesics as parameterized by proper time. This is expressed mathematically by the geodesic equation:

where

- is a Christoffel symbol (otherwise known as a connection).

Since x is a rank one tensor, these equations are four in number, with each one describing the second derivative of a coordinate with respect to proper time. (Note that under the Minkowski metric of special relativity, the values of the connections are all zeros. This is what turns the general relativity geodesic equations into for special relativity.)

Gravitation

For gravitation, the relationship between Newton's theory of gravity and general relativity is governed by the correspondence principle: General relativity must produce the same results as gravity does for the cases where Newtonian physics has been shown to be accurate.

Around a spherically symmetric object, the theory of gravity predicts that objects will be physically accelerated towards the center on the object by the rule where

- G is the Universal Gravitation constant

- M is the mass of the gravitating object,

- r is the distance to the gravitation object, and

- is a unit vector identifying the direction to the massive object.

In the weak-field approximation of general relativity, an identical coordinate acceleration must exist. For the Schwarzschild solution (which is the simplest possible spacetime surrounding a massive object), the same acceleration as that which (in Newtonian physics) is created by gravity is obtained when a constant of integration is set equal to 2m (where m=MG/c^2). For more information, see Deriving the Schwarzschild solution.

Transition from Newtonian mechanics to general relativity

Some of the basic concepts of general relativity can be outlined outside the relativistic domain. In particular, the idea that mass/energy generates curvature in space and that curvature affects the motion of masses can be illustrated in a Newtonian setting.

General relativity generalizes the geodesic equation and the field equation to the relativistic realm in which trajectories in space are replaced with Fermi-Walker transport along world lines in spacetime. The equations are also generalized to more complicated curvatures.

Transition from special relativity to general relativity

The basic structure of general relativity, including the geodesic equation and Einstein field equation, can be obtained from special relativity by examining the kinetics and dynamics of a particle in a circular orbit about the earth. In terms of symmetry the transition involves replacing a global Lorentz covariance by a local Lorentz covariance.

Conservation of energy-momentum

In classical mechanics, conservation of energy and momentum are handled separately.

In special relativity, energy and momentum are joined in the four-momentum and the stress-energy tensors. For any self-contained system or for any physical interaction, the total energy-momentum is conserved in the sense that:

, where

- is a partial derivative.

- is the stress-energy tensor.

For general relativity, this relationship is modified to account for curvature, becoming

, where

- D is a covariant derivative.

Unlike classical mechanics and special relativity, it is not usually possible to unambiguously define the total energy and momentum in general relativity, so the tensorial conservation laws are local statements only (see ADM energy, though). This often causes confusion in time-dependent spacetimes which apparently do not conserve energy, although the local law is always satisfied. Exact formulation of energy-momentum conservation on an arbitrary geometry requires use of a non-unique stress-energy-momentum pseudotensor.

Electromagnetism

Maxwell's equations, the equations of electrodynamics, in curved spacetime are (cgs units)

and

, where

- F ab is the electromagnetic field tensor, and

- J a is a four-current

- is the covariant derivative.

The effect of an electromagnetic field on a charged object of mass m is then

, where

- P a is the four-momentum of the charged object

- again is the covariant derivative.

Maxwell's equations in flat spacetime are recovered by reverting the covariant derivatives to regular derivatives (see Formulation of Maxwell's equations in special relativity).

Quantum mechanics

Quantum mechanics is viewed as the fundamental theory of physics along with general relativity, but combining quantum mechanics with general relativity has presented difficulties.

Quantum field theory in curved spacetime

Normally, quantum field theorymodels are considered in flat Minkoswki space (or Euclidean space), which is an excellent approximation for weak gravitational fields like those on Earth. In the presence of strong gravitational fields, the principles of quantum field theory have to be modified. The spacetime is static so the theory is not fully relativistic in the sense of general relativity; it is not background independent nor generally covariant under the diffeomorphism group. The interpretation of excitations of quantum fields as particles becomes frame dependent. Hawking radiation is a prediction of this semiclassical approximation.

Einstein gravity is nonrenormalizable

It is often said that general relativity is incompatible with quantum mechanics. This means that if one attempts to treat the gravitational field using the ordinary rules of quantum field theory, one finds that physical quantities are divergent. Such divergences are common in quantum field theories, and can be cured by adding parameters to the theory known as counterterms. Experimentalists must then measure the values of these counterterms in order to be able to use the quantum field theory in question to make predictions [citation needed].

Many of the best understood quantum field theories, such as quantum electrodynamics, contain divergences which are canceled by counterterms that have been effectively measured. One needs to say effectively because the counterterms are formally infinite, however it suffices to measure observable quantities, such as physical particle masses and coupling constants, which depend on the counterterms in such a way that the various infinities cancel.

A problem arises, however, when the cancellation of all infinities requires the inclusion of an infinite number of counterterms. In this case the theory is said to be nonrenormalizable. While nonrenormalizable theories are sometimes seen as problematic, the framework of effective field theories presents a way to get low-energy predictions out of non-renormalizable theories. The result is a theory that works correctly at low energies, though such a theory cannot be considered to be a theory of everything because it cannot be self-consistently extended to the high-energy realm.

Proposed quantum gravity theories

This does not mean that there is no quantum version of Einsteinian gravity. General relativity fits nicely into the effective field theory formalism and makes sensible predictions at low energies (Donoghue, 1995). However, high enough energies will "break" the theory.

It is generally held that one of the most important unsolved problems in modern physics is the problem of obtaining the true quantum theory of gravitation, that is, the theory chosen by nature, one that will work at all energies. Discarded attempts at obtaining such theories include supergravity, a field theory which unifies general relativity with supersymmetry. In the second superstring revolution supergravity has come back into fashion, with its quantum completion rebranded with a new name: M-theory.

A very different approach to that described above is employed by loop quantum gravity. In this approach, one does not try to quantize the gravitational field as one quantizes other fields in quantum field theories. Thus the theory is not plagued with divergences and one does not need counterterms. However it has not been demonstrated that the classical limit of loop quantum gravity does in fact contain flat space Einsteinian gravity. This being said, the universe has only one spacetime and it is not flat.

Of these two proposals, M-theory is significantly more ambitious in that it also attempts to incorporate the other known fundamental forces of Nature, whereas loop quantum gravity "merely" attempts to provide a viable quantum theory of gravitation with a well-defined classical limit which agrees with general relativity.

Alternative theories

Well known classical theories of gravitation other than general relativity include:

- Nordström's theory of gravitation (1913) was one of the earliest metric theories (an aspect brought out by Einstein and Fokker in 1914). Nordström soon abandoned his theory in favor of general relativity on theoretical grounds, but this theory, which is a scalar theory, and which features a notion of prior geometry, does not predict any light bending, so it is solidly incompatible with observation.

- Alfred North Whitehead formulated an alternative theory of gravity that was regarded as a viable contender for several decades, until Clifford Will noticed in 1971 that it predicts grossly incorrect behavior for the ocean tides!

- George David Birkhoff's (1943) yields the same predictions for the classical four solar system tests as general relativity, but unfortunately requires sound waves to travel at the speed of light! Thus, like Whitehead's theory, it was never a viable theory after all, despite making an initially good impression on many experts.

- Like Nordström's theory, the gravitation theory of Wei-Tou Ni (1971) features a notion of prior geometry, but Will soon showed that it is not fully compatible with observation and experiment.

- The Brans-Dicke theory and the Rosen bi-metric theory are two alternatives to general relativity which have been around for a very long time and which have also withstood many tests. However, they are less elegant and more complicated than general relativity, in several senses.

- There have been many attempts to formulate consistent theories which combine gravity and electromagnetism. The first of these, Weyl's gauge theory of gravitation, was immediately shot down (on a postcard!) by Einstein himself,[citation needed] who pointed out to Hermann Weyl that in his theory, hydrogen atoms would have variable size, which they do not. Another early attempt, the original Kaluza-Klein theory, at first seemed to unify general relativity with classical electromagnetism, but is no longer regarded as successful for that purpose. Both these theories have turned out to be historically important for other reasons: Weyl's idea of gauge invariance survived and in fact is omnipresent in modern physics, while Kaluza's idea of compact extra dimensions has been resurrected in the modern notion of a braneworld.

- The Fierz-Pauli spin-two theory was an optimistic attempt to quantize general relativity, but it turns out to be internally inconsistent. Pascual Jordan's work toward fixing these problems eventually motivated the Brans-Dicke theory, and also influenced Richard Feynman's unsuccessful attempts to quantize gravity.

- Einstein-Cartan theory includes torsion terms, so it is not a metric theory in the strict sense.

- Teleparallel gravity goes further and replaces connections with nonzero curvature (but vanishing torsion) by ones with nonzero torsion (but vanishing curvature).

- The Nonsymmetric Gravitational Theory (NGT) of John W. Moffat is a dark horse in the race.

Even for "weak field" observations confined to our Solar system, various alternative theories of gravity predict quantitatively distinct deviations from Newtonian gravity. In the weak-field, slow-motion limit, it is possible to define 10 experimentally measurable parameters which completely characterize predictions of any such theory. This system of these parameters, which can be roughly thought of as describing a kind of ten dimensional "superspace" made from a certain class of classical gravitation theories, is known as PPN formalism (Parametric Post-Newtonian formalism). [3] Current bounds on the PPN parameters [4] are compatible with GR.

See in particular confrontation between Theory and Experiment in Gravitational Physics, a review paper by Clifford Will.

History

- See also: Tests of general relativity

General relativity was developed by Einstein in a process that began in 1907 with the publication of an article on the influence of gravity and acceleration on the behavior of light in special relativity. Most of this work was done in the years 1911–1915, beginning with the publication of a second article on the effect of gravitation on light. By 1912, Einstein was actively seeking a theory in which gravitation was explained as a geometric phenomenon. In 1915, these efforts culminated in the publication of the Einstein field equations, which are a set of differential equations [citation needed].

Since 1915, the development of general relativity has focused on solving the field equations for various cases. This generally means finding metrics which correspond to realistic physical scenarios. The interpretation of the solutions and their possible experimental and observational testing also constitutes a large part of research in GR.

The expansion of the universe created an interesting episode for general relativity. Starting in 1922, researchers found that cosmological solutions of the Einstein field equations call for an expanding universe. Einstein did not believe in an expanding universe, and so he added a cosmological constant to the field equations to permit the creation of static universe solutions. In 1929, Edwin Hubble found evidence that the universe is expanding. This resulted in Einstein dropping the cosmological constant, referring to it as "the biggest blunder in my career".

Progress in solving the field equations and understanding the solutions has been ongoing. Notable solutions have included the Schwarzschild solution (1916), the Reissner-Nordström solution and the Kerr solution.

Observationally, general relativity has a history too. The perihelion precession of Mercury was the first evidence that general relativity is correct. Eddington's 1919 expedition in which he confirmed Einstein's prediction for the deflection of light by the Sun helped to cement the status of general relativity as a likely true theory. Since then, many observations have confirmed the predictions of general relativity. These include studies of binary pulsars, observations of radio signals passing the limb of the Sun, and even the GPS system.

Status

The status of general relativity is decidedly mixed.

On the one hand, general relativity is a highly successful model of gravitation and cosmology. It has passed every unambiguous test that it has been subjected to so far, both observationally and experimentally. It is therefore almost universally accepted by the scientific community.

On the other hand, general relativity is inconsistent with quantum mechanics, and the singularities of black holes also raise some disconcerting issues. So while it is accepted, there is also a sense that something beyond general relativity may yet be found.

Currently, better tests of general relativity are needed. Even the most recent binary pulsar discoveries only test general relativity to the first order of deviation from Newtonian projections in the post-Newtonian parameterizations. Some way of testing second and higher order terms is needed, and may shed light on how reality differs from general relativity (if it does).

Quotes

- Spacetime grips mass, telling it how to move, and mass grips spacetime, telling it how to curve — John Archibald Wheeler.

- The theory appeared to me then, and still does, the greatest feat of human thinking about nature, the most amazing combination of philosophical penetration, physical intuition, and mathematical skill. But its connections with experience were slender. It appealed to me like a great work of art, to be enjoyed and admired from a distance. — Max Born

Notes

See also

- Mathematics of general relativity

- Classical theories of gravitation

- David Hilbert

- Einstein-Hilbert action

- General relativity resources, an annotated reading list giving bibliographic information on some of the most cited resources.

- History of general relativity

- Golden age of general relativity

- Contributors to general relativity

References

- For a more complete list of available publications on general relativity, please see general relativity resources.

- Einstein, A., (1916) The Foundation of the General Theory of Relativity, Annalen der Physik.

- Einstein, A. (1961). Relativity: The Special and General Theory. New York: Crown. ISBN 0-517-029618.

- Ohanian, Hans C. (1994). Gravitation and Spacetime. New York: W. W. Norton. ISBN 0-393-96501-5.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help)

- Wald, Robert M. (1984). General Relativity. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 0-226-87033-2.

- Misner, Charles (1973). Gravitation. San Francisco: W. H. Freeman. ISBN 0-7167-0344-0.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help)

- P. A. M. Dirac (1996). General Theory of Relativity. Princeton University Press. ISBN 0-691-01146-X.

- Donoghue, John F (1995). "Introduction to the Effective Field Theory Description of Gravity". Retrieved 2006-08-26. Lectures presented at the Advanced School on Effective Field Theories (Almunecar, Spain, June 1995), to be published in the proceedings