ZX Spectrum

| |

| Type | Home computer |

|---|---|

| Release date | April 1982 |

| Discontinued | 1984 (Spectrum 48K) 1993 (ZX Spectrum family) |

| Operating system | Sinclair BASIC |

| CPU | Zilog Z80A @ 3.5 MHz |

| Memory | 16 kB / 48 kB / 128 kB |

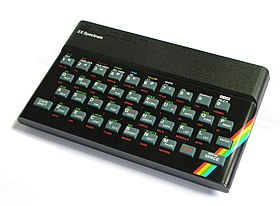

The Sinclair ZX Spectrum was a home computer released in the United Kingdom in 1982 by Sinclair Research. Based on a Zilog Z80 A CPU running at 3.5 MHz, the original Spectrum came with either 16 kB or 48 kB of RAM; later machines had 128 kB of RAM. The hardware designer was Richard Altwasser of Sinclair Research and the software was written by Steve Vickers on contract from Nine Tiles Ltd, the authors of Sinclair BASIC. Sinclair's industrial designer Rick Dickinson was responsible for the machine's outward appearance.[1] Originally dubbed the ZX82[2], the machine was later renamed the "Spectrum" by Sinclair to highlight the machine's colour display, compared to the black-and-white of its predecessors, the ZX80 and ZX81.

Description

Video output was to a TV, for a simple colour graphic display. The chiclet keyboard (on top of a membrane, similar to calculator keys) was marked with Sinclair BASIC keywords, so that, for example, pressing "G" when in programming mode would insert the BASIC command GO TO.[3] Programs and data were stored using a normal cassette recorder.

The Spectrum's video display, although rudimentary by today's standards, was adequate at the time for display on portable TV sets, and did not present much of a barrier to game development. Text could be displayed using 32 columns × 24 rows of characters from the ZX Spectrum character set, with a choice of 8 colours in either normal or bright mode, which gave 15 shades (black was the same in both modes).[4] The image resolution was 256×192 with the same colour limitations.[5] The Spectrum had an interesting method of handling colour; the colour attributes were held in a 32×24 grid, separate from the text or graphical data, but was still limited to only two colours in any given character cell, both of which had to be either bright or non-bright.[5] This led to what was called colour clash or attribute clash with some bizarre effects in arcade style games. This problem became a distinctive feature of the Spectrum and an in-joke among Spectrum users, as well as a point of derision by advocates of other systems. Other machines available around the same time, for example the Amstrad CPC, did not suffer from this problem. The Commodore 64 used colour attributes, but hardware sprites and scrolling were used to avoid attribute clash.

The Spectrum was the first mainstream audience home computer in the UK, similar in significance to the Commodore 64 in the USA. The Commodore 64, often abbreviated to C64, was also the main rival to the Spectrum in the UK market. An enhanced version of the Spectrum with better sound, graphics and other modifications was marketed in the USA by the Timex Corporation as the TS2068.

Educational application

In 1980–82 the UK Department of Education and Science had begun the Microelectronics Education Programme to introduce microprocessing concepts and educational materials. In 1982 through to 1986, the Department of Industry (DoI) allocated funding to assist UK local education authorities to supply their schools with a range of computers; the ZX Spectrum was very useful for the control projects.

Models

ZX Spectrum 16K/48K (1982)

Released by Sinclair in 1982 and available with either 16 kB (GB£125, later £99) or 48 kB (£175, later £129) of RAM [6][7] and 16 kB ROM, the original ZX Spectrum is remembered for its rubber keyboard and diminutive size. Owners of the 16 kB model could purchase an internal 32 kB RAM upgrade daughterboard, which consists of 8 dynamic RAMs and few TTL chips. Users could mail their 16K Spectrums to Sinclair to be upgraded to 48 kB versions. To reduce the price, the 32 kB extension actually comprised eight faulty 64 kilobit chips with only one half of their capacity working and/or available. [8]

Also available were third-party external 32 kB RAMpacks that mounted in the rear expansion slot. As with the ZX81, "RAMpack wobble" caused by poor connection with the expansion was the bane of many users, causing instant crashes and sometimes ULA or CPU burnout.

ZX Spectrum+ (1984)

Planning of the ZX Spectrum+ started in June 1984[9] and was released in October the same year.[10] This 48 kB Spectrum (development code-name TB) introduced a new QL-style enclosure with a much needed injection-moulded keyboard and a reset button, retailing for £179.95[11]. A DIY conversion-kit for older machines was also available. Early on, the machine outsold the rubber-key model 2:1; however, some retailers reported very high failure rates.

ZX Spectrum 128 (1986)

Sinclair developed the 128 (code-named Derby) in conjunction with their Spanish distributor Investrónica.[12] Investrónica had helped adapt the ZX Spectrum+ to the Spanish market after the Spanish government introduced a special tax on all computers with 64 kB RAM or less which did not support the Spanish alphabet (including ñ) and show messages in Spanish.[13]

New features included 128 kB RAM, three-channel audio via the AY-3-8912 chip, MIDI compatibility, an RS-232 serial port, an RGB monitor port, 32 kB of ROM including an improved BASIC editor and an external keypad.

The machine was simultaneously presented for the first time and launched in September 1985 at the SIMO '85 trade show in Spain, with a price of 44.250 pesetas (266 €). Because of the large amount of unsold Spectrum+ models, Sinclair decided not to start selling in the UK until January 1986 at a price of £179.95.[14] No external keypad was available for the UK release, although the ROM routines to utilise it and the port itself, which was hastily renamed "AUX", remained.

The Z80 processor used in the Spectrum has a 16-bit address bus, which means only 64 kB of memory can be addressed. To facilitate the extra 80 kB of RAM the designers utilised a bank switching technique so that the new memory would be available as six pages of 16 kB at the top of the address space. The same technique was also used to page between the new 16 kB editor ROM and the original 16 kB BASIC ROM at the bottom of the address space.

The new sound chip and MIDI out abilities were exposed to the BASIC programming language with the command PLAY and a new command SPECTRUM was added to switch the machine into 48K mode. To enable BASIC programmers to access the additional memory, a RAM disk was created where files could be stored in the additional 80 kB of RAM. The new commands took the place of two existing user-defined-character spaces causing compatibility issues with some BASIC programs.

The Spanish version had the "128K" logo (right, bottom of the computer) in white colour while the English one had the same logo in red colour.

ZX Spectrum +2 (1986)

The +2 was Amstrad's first Spectrum, coming shortly after their purchase of the Spectrum range and "Sinclair" brand. The machine featured an all-new grey enclosure featuring a spring-loaded keyboard, dual joystick ports, and a built-in cassette recorder dubbed the "Datacorder" (like the Amstrad CPC 464), but was (in all user-visible respects) otherwise identical to the ZX Spectrum 128. Production costs had been reduced and the retail price dropped to £139–£149.[15]

The new keyboard did not include the BASIC keyword markings that were found on earlier Spectrums, except for the keywords LOAD, CODE and RUN which were useful for loading software. However, the layout remained identical to that of the 128.

ZX Spectrum +3 (1987)

The Spectrum +3 looked similar to the +2 but featured a built-in 3-inch floppy disk drive (like the Amstrad CPC 6128) instead of the tape drive. It initially retailed for £249[16] and then later £199 and was the only Spectrum capable of running CP/M without additional hardware.

The +3 saw the addition of two more 16 kB ROMs, now physically implemented as two 32 kB chips. One was home to the second part of the reorganised 128K ROM and the other hosted the +3's disk operating system. To facilitate the new ROMs and CP/M, the bank-switching was further improved, allowing the ROM to be paged out for another 16 kB of RAM.

Such core changes brought incompatibilities:

- Removal of several lines on the expansion bus edge connector (video, power, ROMCS and IORQGE); caused many external devices problems; some such as the VTX5000 modem could be used via the "FixIt" device

- Reading a non-existent I/O port no longer returned the last attribute; caused some games such as Arkanoid to be unplayable

- Memory timing changes; some of the RAM banks were now contended causing high-speed colour-changing effects to fail

- The keypad scanning routines from the ROM were removed

Some older 48K, and a few older 128K, games were incompatible with the machine.

The ZX Spectrum +3 was the final official model of the Spectrum to be manufactured, remaining in production until December 1990. Although still accounting for one third of all home computer sales at the time, production of the model was ceased by Amstrad in an attempt to transfer customers to their CPC range.

ZX Spectrum +2A /+2B (1987)

The +2A was produced to homogenise Amstrad's range. Although the case reads "ZX Spectrum +2", the +2A/B is easily distinguishable from the original +2 as the case was restored to the standard Spectrum black.

The +2A was derived from Amstrad's +3 4.1 ROM model, hosting a new motherboard which vastly reduced the chip count, integrating many of them into a new ASIC. The +2A replaced the +3's disk drive and associated hardware with a tape drive, as in the original +2. Originally, Amstrad planned to introduce an additional disk interface, but this never appeared. If an external disk drive was added, the "+2A" on the system OS menu would change to a +3. As with the ZX Spectrum +3 some older 48K, and a few older 128K, games were incompatible with the machine.

The +2B signified a manufacturing move from Hong Kong to Taiwan.

Clones

- See also: Category:ZX Spectrum clones

Sinclair licensed the Spectrum design to Timex which produced their own, largely incompatible, derivatives. However, some of the Timex innovations were later adopted by Sinclair Research. A case in point was the abortive 'Pandora' portable Spectrum, whose ULA had the high resolution video mode pioneered in the TS2068. 'Pandora' had a flat-screen TV monitor and Microdrives and was intended to be Sinclair's business portable — after Alan Sugar bought the computer side of Sinclair, he took one look at it and ditched it. (A conversation between him and UK computer journalist Guy Kewney went thus: GK: "Are you going to do anything with Pandora?" AS: "Have you seen it?" GK: "Yes" AS: "Well then.")

In the UK, Spectrum peripheral vendor Miles Gordon Technology (MGT) released the SAM Coupé as the natural successor with some Spectrum compatibility. However, by this point, the Commodore Amiga and Atari ST had taken hold of the market, leaving MGT in eventual receivership.

Many unofficial Spectrum clones were produced, especially in Eastern Europe and South America. In Russia for example, ZX Spectrum clones were assembled by thousands of small start-ups and distributed though poster ads and street stalls. A non-exhaustive list at Planet Sinclair lists over 50 such clones. Some of them are still being produced, such as the Sprinter.

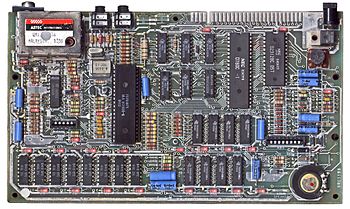

Technical specifications

- CPU

- Zilog Z80A / NEC μPD780C @ 3.50 MHz (Spectrum 16K, 48K, +) or 3.5469 MHz (Spectrum 128 and later)

- Read-only memory (ROM)

- 16 kB ROM (BASIC: Spectrum 16/48K, +)

- 32 kB ROM (BASIC, Editor: Spectrum 128, +2)

- 64 kB ROM (BASIC, Editor, Syntax check, DOS: Spectrum +3, +2A, +2B)

- Random-access memory (RAM)

- 16 kB RAM (Spectrum 16K)

- 48 kB RAM (Spectrum 48K, +)

- 128 kB RAM (Spectrum 128, +2, +3, +2A, +2B)

- Display

- Text: 32×24 characters (8×8 pixels, rendered in graphics mode)

- Graphics: 256×192 pixels, 15 colours (two simultaneous colours — "attributes" — per 8×8 pixels, causing attribute clash)

- Sound

- Beeper (1 channel, 10 octaves and 10+ semitones: Spectrum 16K and 48K via internal speaker, others via TV)

- General Instrument AY-3-8912 chip (3 channels, 9 octaves (PLAY command), 27 Hz to 110.83 kHz (asm): Spectrum 128, +2, +2A, +3)

- I/O

- Z80 bus in/out

- Tape audio in/out for external cassette tape storage (all except Spectrum +2, which had an internal tape recorder)

- RF television out

- RS-232 in/out (128K models)

- MIDI out (128K models)

- RGB monitor out (128K models)

- Joystick inputs × 2 (Spectrum +2, +2A, +3)

- External numeric keypad port (Spectrum 128 and +2)

- Auxiliary interface (previously keypad port) (Spectrum +2A, +3)

- Parallel Printer port (Spectrum +2A, +3)

- Second disk drive port (Spectrum +3)

- Storage

- External cassette tape recorder (all except +2)

- 1–8 external ZX Microdrives (using ZX Interface 1)

- Built-in cassette tape recorder (Spectrum +2, +2A)

- Built-in 3" disk drive (Spectrum +3)

Peripherals

Several peripherals for the Spectrum were marketed by Sinclair: the ZX Printer was already on the market,[17] as the Spectrum had retained the protocol and expansion bus from the ZX81. The ZX Interface 1 add-on module included an 8 kB ROM, an RS-232 serial port, a proprietary LAN interface (called ZX Net), and the ability to connect up to eight ZX Microdrives — somewhat unreliable but speedy tape-loop cartridge storage devices.[18][19] These were later used in a revised version on the Sinclair QL, whose storage format was electrically compatible but logically incompatible with the Spectrum's. Sinclair also released the ZX Interface 2 which added two joystick ports and a ROM cartridge port.[20]

There were also a plethora of third-party hardware addons. The better known of these included the Kempston joystick interface, the Morex Peripherals Centronics/RS-232 interface, the Currah Microspeech unit (speech synthesis),[21] Videoface Digitiser, RAM pack, and Cheetah Marketing SpecDrum (Drum machine), and the Multiface (snapshot and disassembly tool), from Romantic Robot.

There were numerous disk drive interfaces, including the Abbeydale Designers/Watford Electronics SPDOS, Abbeydale Designers/Kempston KDOS, Opus Discovery and the DISCiPLE/+D from Miles Gordon Technology. The SPDOS and KDOS interfaces were the first to come bundled with Office productivity software (Tasword Word Processor, Masterfile database and OmniCalc spreadsheet). This bundle, together with OCP's Stock Control, Finance and Payroll systems, introduced many small businesses to a streamlined, computerised operation.

During the mid-80s, the company Micronet800 launched a service allowing users to connect their ZX Spectrums to a network known as Micronet hosted by Prestel. This service had some similarities to the Internet, but was proprietary and fee-based.

Software

The Spectrum family enjoyed a very large software library of at least 13,000 titles.[22] Despite the fact that the Spectrum hardware was limited by most standards, its software library was very diverse, including programming language implementations (C,[23] Pascal,[24] Prolog,[25] Forth, [26]) several Z80 assemblers/disassemblers (eg: OCP Editor/Assembler, HiSoft Devpac, ZEUS, Artic Assembler), Sinclair BASIC compilers (eg: MCoder, COLT, HiSoft BASIC), Sinclair BASIC extensions (eg: Beta BASIC, Mega Basic), databases (eg: VU-File), word processors (eg: Tasword II), spread sheets (eg: VU-Calc), drawing and painting tools (eg: James Hutchby's OCP Art Studio, Artist, Paintbox, Melbourne Draw), even 3D modelling (VU-3D), and, of course, many, many games.

Famous Spectrum developers

A number of current leading games developers and development companies began their careers on the ZX Spectrum, including Peter Molyneux (ex-Bullfrog Games), David Perry of Shiny Entertainment, and Ultimate Play The Game (now known as Rare, maker of many famous titles for Nintendo game consoles). Other prominent games developers include Matthew Smith (Manic Miner, Jet Set Willy), and Jon Ritman (Match Day, Head Over Heels) and Sid Meier (Silent Service [27])

Software distribution media and copy protection

Tape

Most Spectrum software was originally distributed on audio cassette tapes. The software was encoded on tape as a sequence of pulses that may sound similar to the sounds of a modern day modem. Since ZX Spectrum had only a rudimentary tape interface, data was recorded using an unusually simple and very reliable modulation, similar to pulse-width modulation but without a constant clock rate. Pulses of different widths (durations) represent 0s and 1s. A "zero" is represented by a ~244 μs pulse followed by a gap of the same duration (855 clock ticks each at 3.5 MHz) for a total ~489 μs;[28] "one" is twice as long, totaling ~977 μs. This allows for 1023 "ones" or 2047 "zeros" to be recorded per second. Assuming an even proportion of each, the resulting average speed was ~1365 bit/s. Higher speeds were possible using custom machine code loaders instead of the ROM routines.

Theoretically, a standard 48K program would take about 5 minutes to load: 49152 bytes × 8 = 393216 bits; 393216 bits / 1350 baud ≈ 300 seconds = 5 minutes. In reality, however, a 48K program usually took between 3–4 minutes to load (because of different number of 0s and 1s encoded using pulse-width modulation), and 128K programs could take 12 or more minutes to load. Experienced users could often tell the type of a file, e.g. machine code, BASIC program, or screen image, from the way it sounded on the tape.

The Spectrum was intended to work with almost any cassette tape player, and despite differences in audio reproduction fidelity, the software loading process was quite reliable; however all Spectrum users knew and dreaded the "R Tape loading error, 0:1" message. One common cause was the use of a cassette copy from a tape recorder with a different head alignment to the one being used. This could sometimes be fixed by pressing on the top of the player during loading, or wedging the cassette with pieces of folded paper, to physically shift the tape into the required alignment. A more reliable solution was to realign the head with a small (jeweller's) screwdriver which was easily accessible on a number of tape players.

Typical settings for loading were ¾ volume, 100% treble, 0% bass. Audio filters like loudness and Dolby Noise Reduction had to be disabled, and it was not recommended to use a Hi-Fi player to load programs. There were some tape recorders built specially for digital use, such as the Timex Computer 2010 Tape Recorder.

Complex loaders with unusual speeds or encoding were the basis of the ZX Spectrum copy prevention schemes, although other methods were used including asking for a particular word from the documentation included with the game — often a novella — or the notorious Lenslok system. This had a set of plastic prisms in a fold-out red plastic holder: the idea was that a scrambled word would appear on the screen, which could only be read by holding the prisms at a fixed distance from the screen courtesy of the plastic holder. This relied rather too much on everyone using the same size television, and Lenslok became a running joke with Spectrum users.

One very interesting kind of software was copiers. Most were copyright infringement oriented, and their function was only tape duplication, but when Sinclair Research launched the ZX Microdrive, copiers were developed to copy programs from audio tape to microdrive tapes, and later on diskettes. Best known were the Lerm suite produced by Lerm Software, Trans Express by Romantic Robot, and others. As the protections became more complex (e.g. Speedlock) it was almost impossible to use copiers to copy tapes, and the loaders had to be cracked by hand, to produce unprotected versions. Special hardware, like the Romantic Robot's Multiface which was able to dump a copy of the ZX Spectrum RAM to disk/tape at the press of a button, was developed, entirely circumventing the copy protection systems.

ZX Microdrive

The ZX Microdrive system was released in July 1983 and quickly became quite popular with the Spectrum user base due to the low cost of the drives, however, the actual media was very expensive for software publishers to use for mass market releases (by a factor of 10× compared to tape duplication). Furthermore, the cartridges themselves acquired a reputation for unreliability, and publishers were reluctant to QA each and every item shipped.[29] Hence the main use became to complement tape releases, usually utilities and niche products like the Tasword word processing software and the aforementioned Trans Express. No games are known to be exclusively released on Microdrive, but some companies allowed, and even aided, their software to be copied over. One such example was Rally Driver by Five Ways Software Ltd.

Floppy disk

Several floppy disk systems were designed for the ZX Spectrum. The most popular (except in East Europe) were the DISCiPLE and +D systems released by Miles Gordon Technology in 1987 and 1988 respectively. Despite becoming very popular and were very reliable (from using standard Shugart disk drives), again mostly utility software were released for them. However, both systems had the ability to store memory images onto disk, snapshots, which later on could be loaded back into the ZX Spectrum and execution would commence from the point where they were "snapped", making them perfect for "backups". Both systems were also compatible with the Microdrive command syntax, which made porting existing software much simpler.

The ZX Spectrum +3 featured a built-in disk drive and enjoyed much more success when it came to commercial software releases. More than 700[22] titles were released on 3-inch disk from 1987 to 1997.

Others

In addition, software was also distributed through print media, fan magazines and books. The prevalent language for distribution was the Spectrum's BASIC dialect Sinclair BASIC. The reader would type the software into the computer by hand, run it, and save it to tape for later use. The software distributed in this way was in general simpler and slower than its assembly language counterparts, and lacked graphics. But soon, magazines were printing long lists of checksummed hexadecimal digits with machine code games or tools. There was a vibrant scientific community built around such software, ranging from satellite dish alignment programs to school classroom scheduling programs.

One unusual software distribution method were radio or television shows in e.g. Belgrade (Ventilator 202), Poland, Czechoslovakia, Romania or Brazil, where the host would describe a program, instruct the audience to connect a cassette tape recorder to the radio or TV and then broadcast the program over the airwaves in audio format.

Another unusual method which was used by some magazines were 7" 33⅓ rpm "flexidisc" records, not the hard vinyl ones, which could be played on a standard record player. These disks were known as "floppy ROMs".

Spectrum software in popular music

A few pop musicians included Sinclair programs on their records. The Buzzcocks front man, Pete Shelly, put a Spectrum program including lyrics and other information as the last track on his XL-1 album. The punk band Inner City Unit put a Spectrum database of band information on their 1984 release, 'New Anatomy'. Also in 1984, the Thompson Twins released a game on vinyl.[30] The Freshies had a brief flirtation with fame and Spectrum games, and the Aphex Twin included various loading noises on his Richard D. James album in 1996—most notably part of the loading screen from Sabre Wulf on Corn Mouth. Shakin' Stevens included his Shaky Game at the end of his The Bop Won't Stop album. The aim of the game was to guide your character around a maze, while avoiding bats. Upon completion your score would be given in terms of a rank of disc, e.g. "gold" or "platinum". The game had a minor connection with one of his tracks, It's Late.

There was also a music program for the Spectrum 48K which allowed to play two notes at a time, by rapidly switching between the waveforms of the two separate notes, a big improvement over the mono Spectrum sound. The program was branded after the popular 80's pop band Wham!, and some of the biggest hits of this group could be played with the Spectrum. The program was called Wham! The Music Box and released by Melbourne House, one of the most prolific publishing houses at the time.

Spectrum software today

As audio tapes have a limited shelf-life, most Spectrum software has been digitized in recent years and is available for download in digital form. The legality of this practice is still in question. However, it seems unlikely that any action will ever be taken over such so-called "abandonware".

One popular program for digitizing Spectrum software is Taper: it allows connecting a cassette tape player to the line in port of a sound card or, through a simple home-built device, to the parallel port of a PC. Once in digital form, the software can be executed on one of many existing emulators, on virtually any platform available today. Today, the largest on-line archive of ZX Spectrum software is The World of Spectrum site with more than 12,000 titles.

The Spectrum enjoys a vibrant, dedicated fan-base. Since it was cheap and simple to learn to use and program, the Spectrum was the starting point for many programmers and technophiles who remember it with nostalgia. The hardware limitations of the Spectrum imposed a special level of creativity on game designers, and for this reason, many Spectrum games are very creative and playable even by today's standards.

Notable titles

Your Sinclair top 10

Between October 1991 and February 1992 Your Sinclair published a list of what they considered to be the top 100 games for the ZX Spectrum. Their top 10 were: [31][32]

- Top 3

-

2. Rebelstar

- The rest

CRASH top 10

Between August and December 1991 CRASH published their list of the top 100 ZX Spectrum games, including in the top 10: [33]

- Top 3

- The rest

- RoboCop 2

- Dizzy

- Target: Renegade

- Magicland Dizzy

- Batman: The Movie

- Operation Wolf

- Midnight Resistance

In CRASH's Top 10 all but the Dizzy games were published by Ocean Software. It is also interesting to note that all but one of the Your Sinclair Top 10 games were released in 1987 or before (the conversion of Rainbow Islands did not appear until 1989, although the original was released in 1987), in comparison to the CRASH Top 10 which exclusively features games released in 1987 or after. 1987 was the year in which use of the newer 128K architecture and of the newer AY-3-8912 sound chip began to take off. Indeed, all of CRASH's Top 10, with the exception of Dizzy, made use of these new features with enhanced sound and preloaded levels (eliminating the need for a multiload), reflecting a difference in the attitudes of the editorship and readership of the two magazines.

See also: World of Spectrum top 100

Additional screenshots

- For more screenshots, see Category:ZX Spectrum game screenshots

Notable authors

- Matthew Smith

- Pete Cooke

- James Hutchby

- Jonathan 'Joffa' Smith

- Mike Follin

- Jon Ritman

- The Oliver Twins

- Mike Singleton

- Bo Jangeborg

Magazines

Dedicated

General with Spectrum coverage

- Computer Gamer

- Computer and Video Games

- Computing Today

- Popular Computing Weekly

- Your Computer

- The Games Machine

See also

- History of computing hardware (1960s-present)

- ZX Spectrum demos

- ZX Spectrum character set

- Sinclair BASIC

- ZX Spectrum graphic modes

- List of ZX Spectrum games

- List of cancelled ZX Spectrum games

- Microelectronics Education Programme

References

- ^ Owen, Chris. "ZX Spectrum 16K/48K". Planet Sinclair. Retrieved 2006-08-15.

- ^ Klooster, Erik. "SINCLAIR ZX SPECTRUM : the good, old 'speccy'". Computer Museum. Retrieved 2006-04-19.

- ^ Vickers, Steven (1982). "Basic programming concepts". Sinclair ZX Spectrum BASIC Programming. Sinclair Research Ltd. Retrieved 2006-09-19.

{{cite book}}: External link in|chapterurl=|chapterurl=ignored (|chapter-url=suggested) (help) - ^ Vickers, Steven (1982). "Introduction". Sinclair ZX Spectrum BASIC Programming. Sinclair Research Ltd. Retrieved 2006-08-23.

{{cite book}}: External link in|chapterurl=|chapterurl=ignored (|chapter-url=suggested) (help) - ^ a b Vickers, Steven (1982). "Colours". Sinclair ZX Spectrum BASIC Programming. Sinclair Research Ltd. Retrieved 2006-08-23.

{{cite book}}: External link in|chapterurl=|chapterurl=ignored (|chapter-url=suggested) (help) - ^ "The High Street Spectrum". ZX Computing: 43. 1983.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ "News: Spectrum prices are slashed". Sinclair User (15): 13. 1983. Retrieved 2006-08-15.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Goodwin, Simon (1984). "Suddenly, it's the 64K Spectrum!". Your Spectrum (7): 33–34. Retrieved 2006-08-21.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Denham, Sue (1984). "The Secret That Was Spectrum+". Your Spectrum (10): 104. Retrieved 2006-08-21.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Owen, Chris. "ZX Spectrum+". Planet Sinclair. Retrieved 2006-08-21.

- ^ "News: New Spectrum launch". Sinclair User (33): 11. 1984. Retrieved 2006-08-19.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Bourne, Chris (1985). "News: Launch of the Spectrum 128 in Spain". Sinclair User (44): 5. Retrieved 2006-08-15.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ "Why QWERTY". Retrieved 2006-08-15.

- ^ "Clive discovers games — at last". Sinclair User (49): 53. 1985. Retrieved 2006-08-20.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Phillips, Max (1986). "ZX Spectrum +2". Your Sinclair (11): 47. Retrieved 2006-08-29.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ South, Phil (1987). "It's here... the Spectrum +3". Your Sinclair (17): 22–23.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Owen, Chris. "ZX Printer". Planet Sinclair. Retrieved 2006-08-24.

- ^ "News: Some surprises in the Microdrive". Sinclair User (18): 15. 1983. Retrieved 2006-08-29.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Adams, Stephen (1983). "Hardware World: Spectrum receives its biggest improvement". Sinclair User (19): 27–29. Retrieved 2006-08-29.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ "Hardware World: Sinclair cartridges may be out of step". Sinclair User (21): 35. 1983. Retrieved 2006-08-29.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ "Hardware World: Clear speech from Currah module". Sinclair User (21): 40. 1983. Retrieved 2006-08-29.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ a b Heide, Martijn van der. "Archive!". World of Spectrum. Retrieved 2006-08-11.

- ^ Heide, Martijn van der. "Sinclair Infoseek: HiSoft C". World of Spectrum. Retrieved 2006-08-24.

- ^ Heide, Martijn van der. "Sinclair Infoseek: HiSoft Pascal 4". World of Spectrum. Retrieved 2006-08-24.

- ^ Heide, Martijn van der. "Sinclair Infoseek: Micro-Prolog". World of Spectrum. Retrieved 2006-08-24.

- ^ Heide, Martijn van der. "Sinclair Infoseek: Forth". World of Spectrum. Retrieved 2006-08-24.

- ^ "Silent Service". CRASH (38): 79–80. 1987.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Heide, Martijn van der (1997 – 1999). "Selecting a sample rate". Tape decoding with Taper. Retrieved 2006-08-24.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|year=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ "Microdrive revisited". CRASH (22). 1985. Retrieved 2006-08-10.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Heide, Martijn van der. "Sinclair Infoseek: Thompson Twins Adventure, The". World of Spectrum. Retrieved 2006-08-24.

- ^ "The YS Top 100 Speccy Games Of All Time (Ever!)". Your Sinclair (73): 34–36. 1992. Retrieved 2006-08-15.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ "The YS Top 100 Speccy Games Of All Time Pt 5". Your Sinclair (74): 45. 1992. Retrieved 2006-08-15.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ "All Time Encyclopedia Top 100 Speccy Games". CRASH (94): 45–48. 1991. Retrieved 2006-08-15.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)

External links

- World of Spectrum – Run by a Dutch fan and officially endorsed by Amstrad; many resources available for downloading

- comp.sys.sinclair FAQ

- Planet Sinclair - Spectrum pages

- Category at ODP

- ZX Planet - Spectrum Heaven

- old-computers.com - page on the Spectrum

- ZX Spectrum Webring

- ZXF magazine

- The Incomplete Spectrum ROM Assembly and actual assembly listing

- ZX Spectrum Flickr group Many photos and images at Flickr.com