2019 Atlantic hurricane season

| 2019 Atlantic hurricane season | |

|---|---|

Season summary map | |

| Seasonal boundaries | |

| First system formed | May 20, 2019 |

| Last system dissipated | December 2, 2019 |

| Strongest storm | |

| Name | Dorian |

| • Maximum winds | 185 mph (295 km/h) (1-minute sustained) |

| • Lowest pressure | 910 mbar (hPa; 26.87 inHg) |

| Seasonal statistics | |

| Total depressions | 20 |

| Total storms | 18 |

| Hurricanes | 6 |

| Major hurricanes (Cat. 3+) | 3 |

| Total fatalities | ≥ 111 total |

| Total damage | > $11.38 billion (2019 USD) |

| Related articles | |

The 2019 Atlantic hurricane season was the fourth consecutive year of above-average and damaging seasons dating back to 2016. It is tied with 1969 as the fourth-most active Atlantic hurricane season on record in terms of named storms,[nb 1] with 18 named storms and 20 tropical cyclones in total, although many were weak and short-lived, especially towards the end of the season. The season officially began on June 1 and ended on November 30. These dates historically describe the period each year when most tropical cyclones form in the Atlantic basin and are adopted by convention. However, tropical cyclogenesis is possible at any time of the year, as demonstrated by the formation of Subtropical Storm Andrea on May 20, marking the record fifth year in a row where a tropical or subtropical cyclone developed before the official start of the season, breaking the previous record of four consecutive years set in 1951–1954.[1] For a second year in a row, no tropical cyclones formed during the month of June.

The season's first hurricane, Barry, formed in mid-July in the northern Gulf of Mexico and struck Louisiana. After five weeks of inactivity, the tropics began to ramp up in late August with a few storms developing, including Hurricane Dorian, which struck the Windward Islands and United States Virgin Islands as a strengthening tropical cyclone and then rapidly intensified into a Category 5 hurricane on approach to the Bahamas, where it devastated the northwesternmost islands before proceeding up the Eastern Seaboard, where it also caused considerable damage.

In September, Tropical Storm Fernand quickly formed near the Mexican coast and proceeded to make landfall in Tamaulipas, Mexico, causing severe flash flooding across the state. Hurricane Humberto brought heavy rains and hurricane-force winds to Bermuda for the first time since Hurricane Nicole in 2016. Tropical Storm Imelda quickly formed over the Gulf of Mexico before it made landfall in Texas, causing catastrophic flooding as it slowed to a crawl over the state. Lorenzo became the easternmost Category 5 Atlantic hurricane on record, and the French ship Bourbon Rhode sank after sailing through it. Additionally, Tropical Storm Nestor caused a tornado outbreak across west Florida in mid-October, causing moderate damage to the same area affected by Hurricane Michael the previous year. Tropical Storm Olga also caused moderate damage and heavy flooding over the Western Gulf Coast. Hurricane Pablo became the easternmost hurricane formation on record, besting Hurricane Vince. The season concluded with Tropical Storm Sebastien, a persistent November cyclone. With Dorian and Lorenzo, the season became the fourth consecutive season to feature at least one Category 5 hurricane (Matthew in 2016; Irma and Maria in 2017 and Michael in 2018). It also became one of the seven seasons to feature multiple Category 5 hurricanes.

Seasonal forecasts

| Source | Date | Named storms |

Hurricanes | Major hurricanes | |

| Average (1981–2010)[2] | 12.1 | 6.4 | 2.7 | ||

| Record high activity | 28 | 15 | 7 | ||

| Record low activity | 4 | 2† | 0† | ||

| ––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––– | |||||

| TSR[3] | December 11, 2018 | 12 | 5 | 2 | |

| CSU[4] | April 4, 2019 | 13 | 5 | 2 | |

| TSR[5] | April 5, 2019 | 12 | 5 | 2 | |

| NCSU[6] | April 16, 2019 | 13–16 | 5–7 | 2–3 | |

| TWC[7] | May 6, 2019 | 14 | 7 | 3 | |

| UKMO[8] | May 21, 2019 | 13* | 7* | 3* | |

| NOAA[9] | May 23, 2019 | 9–15 | 4–8 | 2–4 | |

| TSR[10] | May 30, 2019 | 12 | 6 | 2 | |

| CSU[11] | June 4, 2019 | 14 | 6 | 2 | |

| UA[12] | June 11, 2019 | 16 | 8 | 3 | |

| TSR[13] | July 4, 2019 | 12 | 6 | 2 | |

| CSU[14] | July 9, 2019 | 14 | 6 | 2 | |

| CSU[15] | August 5, 2019 | 14 | 7 | 2 | |

| TSR[16] | August 6, 2019 | 13 | 6 | 2 | |

| NOAA[17] | August 8, 2019 | 10–17 | 5–9 | 2–4 | |

| ––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––– | |||||

| Actual activity | 18 | 6 | 3 | ||

| * June–November only. † Most recent of several such occurrences. (See all) | |||||

Ahead of and during the season, several national meteorological services and scientific agencies forecast how many named storms, hurricanes, and major hurricanes (Category 3 or higher on the Saffir–Simpson scale) will form during a season and/or how many tropical cyclones will affect a particular country. These agencies include the Tropical Storm Risk (TSR) Consortium of University College London, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) and Colorado State University (CSU). The forecasts include weekly and monthly changes in significant factors that help determine the number of tropical storms, hurricanes, and major hurricanes within a particular year. Some of these forecasts also take into consideration what happened in previous seasons and the state of the El Niño–Southern Oscillation (ENSO). On average, an Atlantic hurricane season between 1981 and 2010 contained twelve tropical storms, six hurricanes, and three major hurricanes, with an accumulated cyclone energy (ACE) index of between 66 and 103 units.[2]

Pre-season outlooks

The first forecast for the year was released by TSR on December 11, 2018, which predicted a slightly below-average season in 2019, with a total of 12 named storms, 5 hurricanes, and 2 major hurricanes, due to the anticipated presence of El Niño conditions during the season.[3] On April 4, 2019, CSU released its forecast, predicting a near-average season of 13 named storms, 5 hurricanes and 2 major hurricanes.[4] On April 5, TSR released an updated forecast that reiterated its earlier predictions.[5] North Carolina State University released their forecast on April 16, predicting slightly-above average activity with 13–16 named storms, 5–7 hurricanes and 2–3 major hurricanes.[6] On May 6, the Weather Company predicted a slightly-above average season, with 14 named storms, 7 hurricanes, and 3 major hurricanes.[7] The UK Met Office released their forecast May 21, predicting 13 named storms, 7 hurricanes, 3 major hurricanes and an accumulated cyclone energy of 109 units.[8] On May 23, NOAA released their first prediction, calling for a near-normal season with 9–15 named systems, 4–8 hurricanes, and 2–4 major hurricanes.[9] On May 30, TSR released an updated forecast which increased the number of forecast hurricanes from 5 to 6.[10]

Mid-season outlooks

On June 4, CSU updated their forecast to include a total of 14 named storms, 6 hurricanes and 2 major hurricanes, including Subtropical Storm Andrea.[11] On June 11, University of Arizona (UA) predicted above-average activities: 16 named storms, 8 hurricanes, 3 major hurricanes, and accumulated cyclone energy index of 150 units.[12] On July 4, the TSR released their first mid-season outlook, still retaining their numbers from the previous forecast.[13] On July 9, CSU released their second mid-season outlook with the same remaining numbers from their previous forecast.[14] On August 5, the CSU released their third mid-season outlook, still retaining the same numbers from their previous forecast except the slight increase of the number of hurricanes.[15] On August 6, the TSR released their second and final mid-season outlook, with the only changes of increasing the number of named storms from 12 to 13.[16] On August 8, NOAA released their second prediction with increasing the chances for 10–17 named storms, 5–9 hurricanes, and 2–4 major hurricanes,[17] suggesting above-average activity.

Seasonal summary

For a record fifth consecutive year, activity began before the official start of the season when Subtropical Storm Andrea formed on May 20. No storms formed in the month of June,[18] but activity resumed in July when Hurricane Barry formed. Tropical Depression Three formed soon afterwards. After the dissipation of Three less than 24 hours later, activity paused again.[19] However, nearly a month later, on August 21, Tropical Storm Chantal formed, making the 2019 hurricane season the second latest starting season of the 21st century.[citation needed] Early on August 24, Chantal dissipated. Later that day, the tropical depression that would become Hurricane Dorian formed. On August 26, a tropical depression formed off the coast of North Carolina. It would intensify into Tropical Storm Erin late next night.[20] On September 3, Tropical Storm Fernand and Tropical Storm Gabrielle formed. It lasted a week before becoming extratropical and dissipating. Soon after Gabrielle completed extratropical transition, a potential tropical cyclone formed which would later become Hurricane Humberto.[21]

On September 17, two tropical depressions formed in a boom of activity in multiple cyclone basins: one in the Gulf of Mexico rapidly developed into Tropical Storm Imelda shortly before making landfall in Texas, and the other one was named Jerry on September 18. Another duo of tropical cyclones formed on September 22. One was Tropical Storm Karen in the Caribbean Sea. The other one was Tropical Depression Thirteen which eventually became Tropical Storm Lorenzo on the next day.[21] On September 28, Hurricane Lorenzo became the easternmost Category 5 hurricane on record, which also made 2019 the seventh hurricane season to feature multiple Category 5 hurricanes.[citation needed] On October 11, Subtropical Storm Melissa formed, which later developed into a tropical storm before it dissipated several days later on October 14. That same day, a short-lived tropical depression developed off the coast of Africa, and degenerated into a trough on October 16. Meanwhile, a disturbance in the Caribbean Sea emerged into the Gulf of Mexico on October 17 and was designated Potential Tropical Cyclone Sixteen, which later developed into Tropical Storm Nestor on October 18. An unusual amount of activity occurred in late October with the formation of two tropical cyclones on October 25: Olga in the Gulf of Mexico, and Pablo near the Azores. Olga proceeded to be absorbed by a cold front, lasting only 6 hours as a named tropical storm, its remnants bringing heavy rain and tornadoes to the U.S. Meanwhile, Tropical Storm Pablo intensified into the sixth hurricane of the season, becoming the easternmost cyclone to do so, breaking the record set in 2005 by Hurricane Vince. Shortly after Pablo became post-tropical, on October 30, Subtropical Storm Rebekah formed west of the Azores, before becoming extratropical two days later.[22] On November 19, Tropical Storm Sebastien developed northeast of the Leeward Islands and dissipated late on December 2 near the Azores.

The accumulated cyclone energy (ACE) index for the 2019 Atlantic hurricane season was 130 units.[nb 2]

Systems

Subtropical Storm Andrea

| Subtropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | May 20 – May 21 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 40 mph (65 km/h) (1-min); 1006 mbar (hPa) |

An upper-level trough originating in the mid-latitudes cut off into a broad upper-level low over Florida on May 17. The low moved eastward over the western Atlantic during the next day as a large area of cloudiness and showers developed to its east, and on May 19, it began to interact with low-level vorticity along the western edge of a dissipating cold front. The two systems had coalesced into a broad area of low pressure by 12:00 UTC on May 20, and convection associated with the low became better organized throughout that day as the system moved northward. By 22:00 UTC, an Air Force reconnaissance flight found that the system had acquired a well-defined center of circulation, and was producing gale-force winds well away from the center. Based on the aircraft data and the structure of the system, the National Hurricane Center (NHC) estimated that the system became Subtropical Storm Andrea at 18:00 UTC on May 20. However, the cyclone soon began to entrain dry air into its circulation while southwesterly wind shear increased, resulting in a rapid waning of the convection. By 12:00 UTC on May 21, Andrea's convection had dissipated, and the cyclone degenerated into a remnant low. The remnant low moved east-northeastward through the following day until it was absorbed by a cold front at 12:00 UTC on May 22.[23]

Hurricane Barry

| Category 1 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | July 11 – July 15 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 75 mph (120 km/h) (1-min); 993 mbar (hPa) |

A mesoscale convective vortex in the Midwest began moving south, towards the Gulf of Mexico.[24] On July 6, the NHC began monitoring it over the Tennessee Valley and forecast it to move southwards, emerge into the northeastern Gulf of Mexico, and potentially develop into a tropical cyclone within the next several days.[25][26][27] Over the next few days, the trough drifted southward, due to the steering influence of a ridge of high pressure, and the trough developed a broad area of low pressure on July 9, shortly before the system entered the Gulf of Mexico from the Florida Panhandle.[28] The low-pressure system, while still lacking a well-defined center of circulation, became a little better defined on the following day. As the system had a high potential of producing tropical storm conditions and storm surge along the coast of Louisiana within the next couple of days, the NHC initiated advisories on Potential Tropical Cyclone Two at 15:00 UTC on July 10.[29] The system subsequently organized into a tropical storm at 15:00 UTC on July 11, receiving the name Barry.[30] The system slowly moved westward, affecting the U.S. Gulf Coast. The system finally strengthened into a hurricane at 15:00 UTC on July 13, making it the first of the season.[31] However, three hours later, at 18:00 UTC, wind shear began to increase, causing the system to begin weakening. Around that time, Barry made landfall on Intracoastal City, Louisiana, as a Category 1 hurricane, before weakening to tropical storm status afterward,[31][32] causing extensive damage to Lafayette, Lake Charles, and Baton Rouge. Barry gradually weakened while slowly moving inland, weakening into a tropical depression at 21:00 UTC on July 14.[33] At 21:00 UTC on July 15, Barry weakened into a remnant low over northern Arkansas.[34] During the next several days, Barry's remnant moved eastward while gradually weakening,[35] before being absorbed into another frontal system off the coast of New Jersey on July 19.[36]

Barry caused one fatality, with a man killed by a rip current off the coast of the Florida Panhandle on July 15.[37] Damage from the storm is currently at $600 million (2019 USD).[38]

Tropical Depression Three

| Tropical depression (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | July 22 – July 23 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 35 mph (55 km/h) (1-min); 1013 mbar (hPa) |

A tropical wave moved off the west coast of Africa on July 12, producing minimal convection as it moved westward across the tropical Atlantic for several days thereafter. The wave fractured as it approached the Lesser Antilles on July 18, with the northern portion turning northwestward and the southern portion continuing westward across the Caribbean Sea. The northern portion of the wave produced intermittent disorganized convection as it continued westward, reaching the southeastern Bahamas on July 21. Early the following day, a concentrated area of deep convection developed, resulting in the formation of a tropical depression at 12:00 UTC on July 22. However, environmental conditions proved unfavorable for the depression to strengthen, and deep convection decreased substantially shortly after formation. Although a small area of convection re-developed on July 23, it was insufficient to maintain the cyclone, and it degenerated into an open trough at 12:00 UTC on July 23.[39]

Tropical Storm Chantal

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | August 20 – August 23 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 40 mph (65 km/h) (1-min); 1007 mbar (hPa) |

On August 14, a cold front moved across the Southeastern United States and became nearly stationary during the next few days. The pressure gradient between the frontal trough and an area of high pressure over the western Atlantic generated moderate southwesterly winds just off the coast. A small low-pressure system developed over southern South Carolina at 12:00 UTC on August 17 as a result of shear vorticity generated by the difference in winds between land and ocean. The small low moved northeastward across the coastal Carolinas, emerging over the Atlantic Ocean just south of Oregon Inlet at 18:00 UTC August 18. Although the low maintained a well-defined circulation through the following day, shower and thunderstorm activity remained poorly organized. On August 20, however, a more well-defined circulation had developed, and by 18:00 UTC, the system became a tropical depression. Later that evening, scatterometer data indicated the presence of tropical storm-force winds, and the depression strengthened into Tropical Storm Chantal at 00:00 UTC on August 21. However, marginal sea surface temperatures and moderate-to-strong southwesterly shear prevented Chantal from strengthening further, and it weakened to a tropical depression by 00:00 UTC on August 22. Chantal continued to gradually weaken, and by 18:00 UTC August 23, the depression degenerated into a remnant low as deep convection dissipated. The remnant low executed a slow clockwise loop over the next several days, gradually weakening until its dissipation soon after 18:00 UTC August 26.[40]

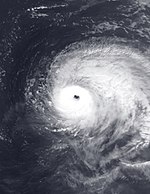

Hurricane Dorian

| Category 5 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | August 24 – September 7 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 185 mph (295 km/h) (1-min); 910 mbar (hPa) |

On August 23, a low-pressure area developed in association with a tropical wave over the open Atlantic Ocean, between the Cape Verde Islands and the Lesser Antilles.[41] The system quickly organized overnight and on August 24, it was classified as a tropical depression several hundred miles east-southeast of Barbados.[42] That same day, it achieved tropical storm status and was given the name Dorian.[43] At first, the system remained small and weak; however, on August 25, it began to strengthen and expand in size.[44] At 1800 UTC on August 28, Dorian reached hurricane status at landfall on the US Virgin Islands. A weather station reported winds of 82 mph (132 km/h) and a gust of 111 mph (179 km/h).[45] There was some dry air still in the system after moving to the north. Eventually, the dry air was expelled from the system, which promoted rapid intensification; Dorian reached Category 3 major hurricane strength on August 30.[46] Rapid intensification continued thereafter, and Dorian reached Category 4 intensity that night, having intensified from a Category 2 hurricane to a Category 4 hurricane in just over 9 hours.[47][48] Dorian strengthened into a Category 5 hurricane on September 1. This made 2019 the record fourth consecutive year to feature a Category 5 hurricane, surpassing the three-year period from 2003–2005.[49] The system continued to strengthen rapidly throughout the day, becoming the strongest hurricane to impact the northwestern Bahamas since modern records began. Dorian made landfall on Elbow Cay at 16:40 UTC that day with 1-minute sustained winds of 185 mph (295 km/h); the storm continued strengthening during landfall, with its minimum central pressure bottoming out at 910 millibars (26.87 inHg) a few hours later, reaching peak intensity.[50][51]

At 02:00 UTC on the next day, Dorian made landfall on Grand Bahama near the same intensity, with the same sustained wind speed.[52] A few hours later, Dorian stalled just north of Grand Bahama island, as the Bermuda High situated to the northeast of the storm collapsed.[53][54] Around the same time, the combination of an eyewall replacement cycle and upwelling of cold water caused Dorian to begin weakening.[55] Dorian weakened to a Category 2 hurricane on September 3, before beginning to move northwestward at 15:00 UTC, parallel to the east coast of Florida; Dorian's wind field expanded during this time.[56] At 06:00 UTC on September 5, Dorian moved over the warm waters of the Gulf Stream and completed its eyewall replacement cycle, reintensifying into a Category 3 hurricane.[57] However, several hours later, Dorian moved into a more hostile environment, encountering more wind shear and dry air, which caused the storm to weaken to a Category 2 hurricane, and later to Category 1 intensity, early on September 6.[58] At 12:35 UTC that day, Dorian made landfall on Cape Hatteras, North Carolina as a Category 1 hurricane.[59] On September 7, Dorian transitioned into an extratropical cyclone. At 18:00 UTC that day, Dorian intensified into a Category 2-equivalent extratropical storm, due to baroclinic forcing.[60] Several hours later, at 7:05 p.m. AST on September 7, Dorian made landfall in Sambro Creek, Nova Scotia as a Category 2-equivalent extratropical storm,[61] before making another landfall on the northern part of Newfoundland several hours later.[62] Early on September 9, Dorian weakened and moved away from Atlantic Canada, and the NHC issued their final advisory on the storm.[63]

Dorian killed more than 70 people and caused more than $4.6 billion (2019 USD) in damage, with the vast majority of the deaths and damage occurring in the Bahamas, which was the hardest-hit area by the storm.[64][65][66][67][68]

Tropical Storm Erin

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | August 26 – August 29 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 40 mph (65 km/h) (1-min); 1002 mbar (hPa) |

On August 20, a large upper-level trough, accompanied by a large area of disorganized showers and thunderstorms, formed over the southwestern Atlantic. As the trough weakened, a shortwave moved into the western side of the trough over the Gulf of Mexico, resulting in the formation of a broad area of low pressure on August 22. The low drifted northwestward, moving over southeastern Florida on August 24 and degenerating into a trough of low pressure. However, deep convection increased along the trough early on August 26, and a new low developed. This marked the formation of a tropical depression at 12:00 UTC on August 26. The depression moved southwestward in response to a mid-level high near Florida, although it was poorly-organized due to northwesterly wind shear. Early on August 27, however, a large burst of convection developed, and the depression strengthened into Tropical Storm Erin at 18:00 UTC that day. Around that time, Erin turned sharply northwestward as the mid-level high over Florida weakened and a subtropical ridge strengthened to its northeast. Strong upper-level winds prevented Erin from strengthening further, and the cyclone weakened to a tropical depression at 18:00 UTC August 28. Accelerating northeastward, Erin transitioned into an extratropical cyclone at 12:00 UTC on August 29, and was absorbed by a larger extratropical low twelve hours later.[69]

In Nova Scotia, precipitation from the remnants of Erin was higher than for all of July and August combined before the storm. According to the Meteorological Service of Canada, the Annapolis Valley and the Bay of Fundy region received the most precipitation with a maximum of 162 mm at Parrsboro and 127 mm at Greenwood. Elsewhere, 53 mm fell in Halifax, 79 mm in Yarmouth, and at the peak of precipitation, several stations reported rates greater than 30 mm per hour, resulting in increased runoff, causing flash floods and the wash out of roads.[70] On the New Brunswick side, rain affected the southern part of the province with maximums of 56 mm in Fredericton, 50 mm in Moncton and 44 mm in Saint John.[71] In Prince Edward Island, accumulations ranged from 30 to 60 mm with a maximum of 66 mm in Summerside.[72] However, volunteers' weather stations reported up to 111 mm at Jolicure/Sackville in New Brunswick and up to 95 mm at Borden-Carleton on Prince Edward Island, along the same axis as the Nova Scotia maximums. In Quebec, regions near the Gulf of St. Lawrence also received about 50 mm of rain.[73]

Tropical Storm Fernand

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | September 3 – September 5 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 50 mph (85 km/h) (1-min); 1000 mbar (hPa) |

A broad area of low pressure began to be monitored over the southeast Gulf of Mexico on August 31 for potential tropical cyclone development.[74] The system gradually developed while moving slowly westward. On September 2, the satellite imagery showed that the surface circulation became better defined, and that the system was more concentrated.[75] On September 3, the disturbance was designated as Potential Tropical Cyclone Seven, with a virtually certain chance of tropical cyclone development.[76] Six hours later, the system organized into the seventh tropical depression of the season[77] and rapidly developed into Tropical Storm Fernand.[78] Fernand made landfall just north of La Pesca in Tamaulipas, Mexico, on September 4, bringing heavy rainfall and storm surge.[79] The storm weakened rapidly and dissipated within 12 hours of landfall.[80]

Fernand brought torrential rainfall to the Mexican states of Coahuila, Nuevo León, Tamaulipas, and San Luis Potosí. Fernand also dumped heavy rainfall over South Texas. In preparation for the storm, the Mexican government activated Plan DN-III-E, sending 4,000 troops to the northeastern states to assist in disaster relief. In Nuevo León, schools and public transport lines were closed on September 5 but resumed operations the next day. Of the states, Nuevo León was the hardest hit, suffering at least MX$4.2 billion (US$213 million) in damage. In some places, six months of rain fell in six hours. Landslides were reported near the state's capital, Monterrey. Homes, roads, bridges, and at least 400 schools were damaged. In García, a Venezuelan man died after he was swept away by floodwaters while attempting to clear a drain; the two people he was working with managed to escape. On September 7, governor of Nuevo León, Jaime Rodríguez Calderón, declared a state of emergency to request for state funds to address the damage. Elsewhere, in Tamaulipas, 12 in (300 mm) of rain fell in 48 hours, leading to some coastal flooding.[81][82]

Tropical Storm Gabrielle

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | September 3 – September 10 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 65 mph (100 km/h) (1-min); 995 mbar (hPa) |

On August 30, the NHC began monitoring a tropical wave emerging from the west coast of Africa.[83] Over the next few days, the disturbance slowly organized while moving westward, and the system strengthened into the eighth tropical depression of the season late on September 3, before intensifying further into Tropical Storm Gabrielle overnight.[84][85] Soon afterward, Gabrielle began tracking westward, before turning northeastward and leaving the northern part of the warm waters of the Gulf Stream, on September 9.[86] On the next day, Gabrielle degenerated into an extratropical cyclone. Gabrielle's remnants later struck the British Isles on September 12.[87]

Hurricane Humberto

| Category 3 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | September 13 – September 20 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 125 mph (205 km/h) (1-min); 951 mbar (hPa) |

Early on September 8, at 03:00 UTC, the NHC began monitoring a disturbance to the northeast of the Lesser Antilles for potential tropical cyclone development.[88] During the few days, the disturbance moved westward while remaining disorganized.[89] On September 12, the disturbance rapidly organized over the southeastern Bahamas,[90] and as the system posed an imminent threat to land areas, the NHC initiated advisories on Potential Tropical Cyclone Nine at 21:00 UTC that day.[91] 24 hours later, the system developed into a tropical depression, while moving northwestward,[92] before strengthening further into Tropical Storm Humberto later that day.[93] On September 14, Humberto passed to the east of the Abaco Islands staying just off the eastern coastline.[94] On September 16, at 03:00 UTC, Humberto intensified into a Category 1 hurricane, while turning to the northeast.[95] Humberto further intensified into a Category 3 major hurricane at 00:00 UTC on the next day.[96] It passed just north of Bermuda and brought hurricane-force winds on the island. After passing Bermuda, Humberto slightly strengthened, then weakened, and finally became an extratropical cyclone at 03:00 UTC on September 20.[97]

Hurricane Jerry

| Category 2 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | September 17 – September 24 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 105 mph (165 km/h) (1-min); 976 mbar (hPa) |

On September 9, a tropical wave moved off the coast of Africa and emerged into the Atlantic, and the NHC began to monitor the system for potential tropical development.[98] Tracking slowly westward across the Atlantic, the tropical wave remained disorganized until September 16, when the system's organization significantly increased.[99] On September 17, the disturbance organized into Tropical Depression Ten.[100] Early on September 18, the tropical depression strengthened into a tropical storm and received the name Jerry.[101] The next day, Jerry intensified into a Category 1 hurricane, and 12 hours later, it further intensified to a Category 2 hurricane with sustained winds of 90 kn (105 mph; 165 km/h).[102] A slight increase in upper-level winds caused the storm to weaken back to a tropical storm about 24 hours later.[103] Jerry slowly weakened as it approached the island of Bermuda, and early on September 25, Jerry finally transitioned into a post-tropical cyclone.

Tropical Storm Imelda

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | September 17 – September 19 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 45 mph (75 km/h) (1-min); 1003 mbar (hPa) |

On September 14, the NHC began monitoring an upper-level low off the west coast of Florida for possible tropical development.[104] During the next several days, the system moved westward across the Gulf of Mexico, though the NHC gave the disturbance only a low chance of development. By September 17, the system had reached the east coast of Texas.[105] Soon afterward, organization in the system rapidly increased, and at 17:00 UTC that day, the system organized into Tropical Depression 11, just off the coast of Texas.[106] The storm continued strengthening while approaching land, becoming Tropical Storm Imelda at 17:45 UTC.[107] Shortly thereafter, at 18:30 UTC, Imelda made landfall near Freeport, Texas at peak intensity, with maximum 1-minute sustained winds of 45 mph (75 km/h) and a minimum central pressure of 1,003 millibars (29.6 inHg).[108] Imelda weakened after landfall, becoming a tropical depression at 03:00 UTC on the next day. At that time, the NHC passed on the responsibility for issuing advisories to the Weather Prediction Center (WPC).[109]

Imelda brought catastrophic flooding to Southeast Texas, with more than 40 inches of rain in some areas. It is the fifth-wettest tropical cyclone to strike the continental United States.[110] Total damage from Imelda is estimated to be US$5 billion.[111]

Tropical Storm Karen

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | September 22 – September 27 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 45 mph (75 km/h) (1-min); 1003 mbar (hPa) |

On September 18, the NHC began to monitor a tropical wave midway between Cape Verde and the Lesser Antilles for possible tropical cyclone development.[112] On September 22, the system developed a closed center of circulation and was named Karen just east of Tobago.[113] After crossing the Lesser Antilles and emerging into the Caribbean Sea, Karen weakened to a depression as it turned northwards, heading for Puerto Rico.[114] The next day, it reintensified back to a tropical storm just south of the island.[115] Despite repeated predictions of intensification, the storm remained weak over the next few days due to unfavorable conditions, before the circulation of Karen opened up into a trough on September 27 well to the southeast of Bermuda.

With the formation of Karen, tropical storm warnings and red alerts were issued for Trinidad and Tobago.[116] Karen brought severe flash floods to Tobago, trapping some people in their houses, as well as uprooting trees and causing several power outages.[117] Several roads were blocked due to mudslides and downed trees. In addition, seven boats in Plymouth sank after a jetty broke.[118] It was also announced that all schools would be closed on Monday, September 23.[119] Swells generated by Karen caused flooding and power outages in Caracas and La Guaira.[120] Tropical storm watches were issued for Puerto Rico and the Virgin Islands as Karen was forecasted to move toward those islands.[121] The governor of Puerto Rico declared a state of emergency on September 23 and ordered schools and government offices to close as Karen advances. The Virgin Islands also closed their schools as the storm approached.[122] People who were living in flood-prone areas were asked to seek shelter.[123] Mudslides and power outages were reported in the U.S. Virgin Islands as Karen passed the islands; more than 29,000 people lost power due to the storm in Puerto Rico.[122][124]

Hurricane Lorenzo

| Category 5 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | September 23 – October 2 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 160 mph (260 km/h) (1-min); 925 mbar (hPa) |

On September 19, the NHC began to monitor a tropical wave that was forecast to emerge from the west coast of Africa. On September 22, the tropical wave emerged into the Atlantic Ocean.[125] The system quickly organized afterward, and at 00:00 UTC on the next day, the wave became Tropical Depression Thirteen.[126] Six hours later, the tropical depression strengthened into Tropical Storm Lorenzo over the far eastern Atlantic Ocean.[126] Early on September 25, the storm reached hurricane strength.[126] On the morning of September 26, the storm underwent a period of rapid intensification; Lorenzo's maximum sustained winds increased 45 mph (75 km/h) in 24 hours and brought the storm to its initial peak intensity as a Category 4 hurricane. As Lorenzo began to turn slowly northward, it weakened with the onset of an eyewall replacement cycle on September 27.[126] However, after bottoming out as a low-end Category 3 hurricane, Lorenzo completed its eyewall replacement cycle and began another period of rapid intensification, strengthening into a Category 5 hurricane early on September 29. This made Lorenzo the easternmost Category 5 Atlantic hurricane on record.[126]

After reaching peak intensity, Lorenzo began to weaken again due to upwelling of the cold water beneath the hurricane and rapidly increasing southwesterly wind shear. Lorenzo dropped below major hurricane intensity only 15 hours after its peak intensity, as it approached the Azores. Lorenzo slowly weakened as it passed the islands, and its windfield continued to expand as it began its extratropical transition.[126] Lorenzo became fully extratropical at 12:00 UTC October 2. On October 3 and 4, as an extratropical cyclone, the system battered the British Isles with tropical storm-force winds, causing some damage.[126]

On September 27, a French ship Bourbon Rhode, with 14 crew members on board, sank about 60 nautical miles from the eye of hurricane Lorenzo. Three of them were rescued on a lifeboat; but 7 remain missing.[127] Four of the missing crew have been confirmed dead as of October 2.[128] Additionally, four people drowned after being caught in rip currents in North Carolina.[129] In New York City, three people were swept away by strong waves. One of them was rescued later, but the other two were confirmed dead.[130]

Tropical Storm Melissa

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | October 11 – October 14 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 65 mph (100 km/h) (1-min); 994 mbar (hPa) |

On October 10, a weak non-tropical low-pressure system that had been tracking slowly up the eastern coast of the United States merged with an expansive storm-force nor'easter situated southeast of New England.[131][132] Contrary to forecasts, the system began to show signs of development on the morning of October 11, with shower and thunderstorm activity increasing in organization around the extratropical cyclone's center.[133] Visible satellite imagery showed a large convective rainband in the northern semicircle of the circulation as well as an eye-like feature, indicating that the system was acquiring subtropical characteristics. Development continued in the ensuing hours, leading the National Hurricane Center to initiate advisories on the system at 15:00 UTC, designating it as Subtropical Storm Melissa while the system was at its peak strength.[134] The storm began to weaken slightly, yet at 21:00 the next day, satellite imagery revealed Melissa had convection wrapped around the center, indicating that Melissa made the transition from a subtropical to a tropical storm.[135] Melissa rapidly degenerated over the next day, significantly decreasing in size before becoming extratropical on October 14.

The nor'easter and subsequent (sub)tropical storm caused heavy surf and storm surge along the coast of the Mid-Atlantic States. In Maryland, flooding from increased high tides from the storm forced street closures in Crisfield and Salisbury.[136] In Delaware, waves from the storm caused beach erosion and flooded streets in Bethany Beach while homes and streets were flooded in Dewey Beach.[137][138] Waves from the storm caused coastal flooding in various parts of the Jersey Shore including Long Beach Island and Atlantic City. The flooding forced the cancellation of the first day of the LBI International Kite Festival.[139]

Tropical Depression Fifteen

| Tropical depression (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | October 14 – October 16 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 35 mph (55 km/h) (1-min); 1006 mbar (hPa) |

A vigorous late-season tropical wave, accompanied by a broad area of low pressure and a large mass of deep convection, moved off the west coast of Africa on October 13. The broad low separated from the parent wave, moving slowly northwestward as the wave continued westward across the tropical Atlantic. Thunderstorm activity associated with the low became better organized early the following day, resulting in the formation of a tropical depression at 12:00 UTC October 14. As the depression moved northwestward toward the Cape Verde islands, it encountered a hostile environment of high wind shear and abundant dry air, which prevented further strengthening. The depression quickly became poorly organized, and it degenerated into a broad area of low pressure by 06:00 UTC October 16. The remnant low continued northwestward, producing intermittent convection until its dissipation at 18:00 UTC on October 17.[140]

Tropical Storm Nestor

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | October 18 – October 19 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 60 mph (95 km/h) (1-min); 996 mbar (hPa) |

At 00:00 UTC October 11, the NHC began tracking a broad area of low pressure that was expected to emerge into the southwestern Caribbean Sea over the weekend.[141] On October 14, the disturbance moved inland over Central America, briefly disorganized and brought heavy rains, then emerged off the Bay of Campeche on October 16.[142] The system quickly re-organized as it passed over the warm waters of the Southern Gulf of Mexico, and, due to its threat to the southeastern United States, was designated as Potential Tropical Cyclone Sixteen at 13:00 UTC the next day.[143] Sixteen then quickly intensified the next day, having maximum sustained winds of 50 kn (60 mph; 95 km/h), becoming one of the strongest potential tropical cyclones designated by the National Hurricane Center.[144] It was upgraded to Tropical Storm Nestor soon after.[145] Much of the strong convective thunderstorms related to the storm were displaced to the east and north of the center, giving Nestor an asymmetrical appearance. Nestor then transitioned into an extratropical cyclone early on October 19, after only lasting a mere 18 hours as a tropical cyclone. The NHC continued advisories on Nestor until it moved inland over the Florida Panhandle later the same day.[146]

Rainfall and storm surge from Nestor caused coastal flooding and flash flooding across the Florida Panhandle, with some areas experiencing over 3 inches of rainfall.[147] Nestor brought moderate damage to the Florida Panhandle, mainly due to the much stronger Hurricane Michael striking the same area the previous season.[148] The outer bands produced several tornadoes. The strongest was rated EF2 and was on the ground for 9 miles (14 km)—an uncommonly long track for the region—through western Polk County, from Lakeland Linder International Airport to northwest Polk County, between 10:59PM and 11:29PM on October 18, causing modest damage to homes, overturning a semi truck and sending debris into vehicles as it crossed Interstate 4, and tearing a large portion of roof off of a middle school.[149][150][151][152] An EF0 tornado briefly touched down in central Pinellas County earlier in the evening, causing minor damage and knocking out power, and an EF1 tornado briefly touched down in Cape Coral on Saturday morning.[151][153] Heavy rains from Nestor caused a car crash in South Carolina, which killed three people and left five injured.[154]

Tropical Storm Olga

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | October 25 – October 26 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 40 mph (65 km/h) (1-min); 998 mbar (hPa) |

At 00:00 UTC on October 23, the NHC began to monitor a tropical wave located over Belize. The wave entered the Bay of Campeche the next day and unexpectedly underwent rapid organization, being designated Tropical Depression Seventeen the day after that. The depression continued to strengthen and organize, becoming Tropical Storm Olga on October 25.[155] A mere six hours after being named however, Olga merged with a cold front and became post-tropical. The remnants of Olga caused many tornadoes across the Mobile Area. In Louisiana, over 130,000 customers lost power, including Louis Armstrong New Orleans International Airport.[156] Later, its remnants accelerated northeast and eventually hit Canada, bringing heavy rain and gusty winds to Ontario. Olga's winds also caused Lake Erie to experience a seiche, with water levels at the eastern end of the lake rising by 7.5 ft (2.3 m). Olga's remnants soon dissipated over Quebec.[157]

Hurricane Pablo

| Category 1 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | October 25 – October 28 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 80 mph (130 km/h) (1-min); 977 mbar (hPa) |

On October 25, the NHC identified an area of concentrated thunderstorms embedded within an extratropical cyclone southwest of the Azores. The small area rapidly organized, and gained tropical characteristics nine hours later, becoming Tropical Storm Pablo. Pablo's small size allowed it to easily gain deep convection, as well as an eye-like feature for about 4 hours, even while over cooler sea temperatures. Pablo began to intensify more as it passed near the Eastern Azores on the 26th. The following day, cloud tops around the small eye suddenly cooled and wind speeds increased, leading the NHC to designate Pablo a Category 1 hurricane on October 27 at 15:00 UTC.[158] Upon doing so, Pablo broke the record for becoming a hurricane this far east, at 18.3°W, breaking Hurricane Vince of 2005's record of 18.9°W.[159] After achieving its peak intensity, Pablo finally weakened due to the very cold waters it was traversing. Pablo weakened back to a tropical storm at 03:00 UTC the next day, and continued to weaken as it crawled northward.[160][161] Pablo became devoid of deep convection and was declared post-tropical at 15:00 UTC on October 28.[162]

Subtropical Storm Rebekah

| Subtropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | October 30 – November 1 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 50 mph (85 km/h) (1-min); 982 mbar (hPa) |

On October 27, a large extratropical cyclone formed about 460 miles (760 km) south of Cape Race, Newfoundland. Moving eastwards, the cyclone quickly gained hurricane-force winds, before weakening as it turned north and west in a large counterclockwise loop, making another smaller loop on its way. On October 29, a smaller low-pressure area formed near the center of the original extratropical cyclone, possessing a small wind field more characteristic of a tropical cyclone. Deep convection formed around the center of the new low on October 30 due to increased atmospheric instability despite sea surface temperatures of only 21 °C (70 °F). This led to the designation of Subtropical Storm Rebekah by the NHC at 12:00 UTC. At this time, Rebekah possessed sustained winds of 50 mph (85 km/h), representing the system's peak intensity. On October 31, Rebekah turned to the east then east-northeast, entering a region of low relative humidity, increasing wind shear, and even colder sea surface temperatures. The system rapidly weakened as a result of these unfavorable environmental factors. Rebekah became extratropical once again on November 1 at 06:00 UTC and dissipated later that day about 115 miles (185 km) north of the Azores.[163]

Tropical Storm Sebastien

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | November 19 – December 2 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 65 mph (100 km/h) (1-min); 994 mbar (hPa) |

At 00:00 UTC on November 17, the NHC began monitoring a large area of thunderstorms associated with the interaction of an upper-level low and a surface trough. This led to the development of a broad area of low pressure over the central Atlantic 24 hours later.[164] The system gradually organized, acquiring a surface circulation early on November 19, and after developing a defined center, the system was designated Tropical Storm Sebastien at 15:00 UTC that day.[165] Warm waters and a favorable upper-level atmosphere allowed Sebastien to strengthen, defying forecasters' initial prediction that the storm would undergo extratropical transition before intensifying significantly.[166] By 03:00 UTC November 21, the system had organized significantly and by this point, the NHC's official forecast called for Sebastien to reach Category 1 hurricane intensity.[167] Over the next couple of days, Sebastien became less and less organized and its center became difficult to locate, creating large uncertainty in its future track and intensity, with one NHC forecaster joking about the confusion and diversity among the forecast models.[168] Ultimately, late on the same day, Sebastien's winds increased to 65 mph as it moved northwestward.[169] During the early morning hours of November 23, Sebastien's center reformed to the north and convection around its new center diminished. By 21:00 UTC, the system's cloud pattern began to resemble that of an extratropical cyclone.[170][171] On November 24, Sebastien began a slow extratropical transition, gradually acquiring subtropical and eventually extratropical characteristics as it passed the Azores.[172] Finally, at 03:00 UTC on November 25, the NHC classified Sebastien as a post-tropical cyclone northeast of the Azores and discontinued advisories on the system. Sebastien continued to persist for a couple of days, though. It dissipated on December 2.[173]

Storm names

The following list of names was used for named storms that formed in the North Atlantic in 2019. Retired names, if any, will be announced by the World Meteorological Organization during the 42nd session of the Regional Association IV Hurricane Committee, which will be held in Panama from March 30 - April 3, 2020.[174] The names not retired from this list will be used again in the 2025 season. This was the same list used in the 2013 season, with the exception of the name Imelda, which replaced Ingrid. The names Imelda, Nestor, and Rebekah were used for the first time this year. The name Nestor replaced Noel after 2007, but was not used in 2013, while the name Rebekah replaced Roxanne after 1995, but was not used in previous seasons.[175]

|

Season effects

This is a table of all the storms that have formed in the 2019 Atlantic hurricane season. It includes their duration, names, affected areas, damages, and death totals. Deaths in parentheses are additional and indirect (an example of an indirect death would be a traffic accident), but were still related to that storm. Damage and deaths include totals while the storm was extratropical, a tropical wave, or a low, and all the damage figures are in USD. Potential tropical cyclones are not included in this table.

| Saffir–Simpson scale | ||||||

| TD | TS | C1 | C2 | C3 | C4 | C5 |

| Storm name |

Dates active | Storm category at peak intensity |

Max 1-min wind mph (km/h) |

Min. press. (mbar) |

Areas affected | Damage (USD) |

Deaths | Ref(s) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Andrea | May 20 – 21 | Subtropical storm | 40 (65) | 1006 | Bermuda | None | None | |||

| Barry | July 11 – 15 | Category 1 hurricane | 75 (120) | 993 | Midwestern United States, Eastern United States, Louisiana, Arkansas, Oklahoma, Great Lakes region | $600 million | 0 (1) | [37][38] | ||

| Three | July 22 – 23 | Tropical depression | 35 (55) | 1013 | The Bahamas, Florida | None | None | |||

| Chantal | August 20 – 23 | Tropical storm | 40 (65) | 1007 | East Coast of the United States | None | None | |||

| Dorian | August 24 – September 7 | Category 5 hurricane | 185 (295) | 910 | Windward Islands, Leeward Islands, Puerto Rico, The Northwestern Bahamas, East Coast of the United States, Eastern Canada | >$4.68 billion | 73 (7) | [65][67][66][64] | ||

| Erin | August 26 – 29 | Tropical storm | 40 (65) | 1002 | Cuba, The Bahamas, East Coast of the United States, Atlantic Canada | Minimal | None | |||

| Fernand | September 3 – 5 | Tropical storm | 50 (85) | 1000 | Northeastern Mexico, South Texas | $213 million | 1 | [81][82] | ||

| Gabrielle | September 3 – 10 | Tropical storm | 65 (100) | 995 | Cape Verde, Ireland, United Kingdom | None | None | |||

| Humberto | September 13 – 20 | Category 3 hurricane | 125 (205) | 951 | Hispaniola, Cuba, Bahamas, Southeastern United States, Bermuda, Atlantic Canada, Ireland, United Kingdom | >$1 million | 1 | [176][68] | ||

| Jerry | September 17 – 24 | Category 2 hurricane | 105 (165) | 976 | Leeward Islands, Puerto Rico, Bermuda | None | None | |||

| Imelda | September 17 – 19 | Tropical storm | 45 (75) | 1003 | Texas, Louisiana, Oklahoma, Arkansas | $5 billion | 4 (1) | [177][111] | ||

| Karen | September 22 – 27 | Tropical storm | 45 (75) | 1003 | Windward Islands, Trinidad and Tobago, Venezuela, U.S. Virgin Islands, British Virgin Islands, Puerto Rico | Minimal | None | |||

| Lorenzo | September 23 – October 2 | Category 5 hurricane | 160 (260) | 925 | West Africa, Cape Verde, Azores, Ireland, United Kingdom | $362 million | 19 | [126] | ||

| Melissa | October 11 – 14 | Tropical storm | 65 (100) | 994[nb 3] | Mid-Atlantic States, New England, Nova Scotia | Minimal | None | |||

| Fifteen | October 14 – 16 | Tropical depression | 35 (55) | 1006 | West Africa, Cape Verde | None | None | |||

| Nestor | October 18 – 19 | Tropical storm | 60 (95) | 996 | Central America, Mexico, Southeastern United States | >$150 million | 0 (3) | [178] | ||

| Olga | October 25 – 26 | Tropical storm | 40 (65) | 998 | United States Gulf Coast, Louisiana, Alabama, Mississippi | >$100 million | 1 | [178] | ||

| Pablo | October 25 – 28 | Category 1 hurricane | 80 (130) | 977 | Azores | None | None | |||

| Rebekah | October 30 – November 1 | Subtropical storm | 50 (85) | 982 | Azores | None | None | |||

| Sebastien | November 19 –December 2 | Tropical storm | 65 (100) | 994 | Leeward Islands, Azores | None | None | |||

| Season aggregates | ||||||||||

| 20 systems | May 20 – December 2 | 185 (295) | 910 | >$11.38 billion | ≥ 99 (12) | |||||

See also

- List of Atlantic hurricanes

- List of Atlantic hurricane seasons

- Tropical cyclones in 2019

- 2019 Pacific hurricane season

- 2019 Pacific typhoon season

- 2019 North Indian Ocean cyclone season

- South-West Indian Ocean cyclone seasons: 2018–19, 2019–20

- Australian region cyclone seasons: 2018–19, 2019–20

- South Pacific cyclone seasons: 2018–19, 2019–20

- South Atlantic tropical cyclone

Notes

- ^ This assumes that early records are correct. More reliable counts would not begin until the mid-1960s with the first successful operation of the weather satellite.

- ^ The totals represent the sum of the squares for every (sub)tropical storm's intensity of over 33 knots (38 mph, 61 km/h), divided by 10,000. Calculations are provided at Talk:2019 Atlantic hurricane season/ACE calcs.

- ^ Melissa reached its peak intensity of 65 mph (100 km/h) and 994 mbar as a subtropical storm but later became fully tropical.

References

- ^ Klotzbach, Philip [@philklotzbach] (May 20, 2019). "The Atlantic has now had named storms form prior to 1 June in five consecutive years: 2015–2019. This breaks the old record of named storm formations prior to 1 June in four consecutive years set in 1951–1954" (Tweet). Retrieved May 20, 2019 – via Twitter.

- ^ a b "Background Information: The North Atlantic Hurricane Season". Climate Prediction Center. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. August 9, 2012. Retrieved December 13, 2013.

- ^ a b Mark Saunders; Adam Lea (December 11, 2018). "Extended Range Forecast for Atlantic Hurricane Activity in 2019" (PDF). London, United Kingdom: Tropical Storm Risk.

- ^ a b "2019 Hurricane Season Expected to Be Near Average, Colorado State University Outlook Says". The Weather Channel. Retrieved April 4, 2019.

- ^ a b Mark Saunders; Adam Lea (April 5, 2019). "April Forecast Update for North Atlantic Hurricane Activity in 2019" (PDF). London, United Kingdom: Tropical Storm Risk.

- ^ a b Tracey Peake (April 16, 2019). "NC State Researchers Predict Normal 2019 Hurricane Season for East Coast". Raleigh, North Carolina: NC State University.

- ^ a b Jonathan Erdman; Brian Donegan (May 6, 2019). "2019 Hurricane Season Expected to be Slightly Above Average But Less Active Than Last Year". The Weather Company. Retrieved May 7, 2019.

- ^ a b "North Atlantic tropical storm seasonal forecast 2019". Met Office. May 21, 2019. Retrieved May 23, 2019.

- ^ a b Lauren Gaches (May 23, 2019). "NOAA predicts near-normal 2019 Atlantic hurricane season". NOAA. Retrieved May 23, 2019.

- ^ a b Mark Saunders; Adam Lea (May 30, 2019). "Pre-Season Forecast for North Atlantic Hurricane Activity in 2019" (PDF). London, United Kingdom: Tropical Storm Risk. Retrieved June 3, 2019.

- ^ a b "2019 Hurricane Season Expected to Be Near Average, Colorado State University Outlook Says". The Weather Channel. Retrieved June 5, 2019.

- ^ a b "University of Arizona (UA) Forecasts an Above-Average Hurricane Season" (PDF). University of Arizona. Retrieved June 12, 2019.

- ^ a b Mark Saunders; Adam Lea (July 4, 2019). "July Forecast Update for North Atlantic Hurricane Activity in 2019" (PDF). London, United Kingdom: Tropical Storm Risk.

- ^ a b "ATLANTIC BASIN SEASONAL HURRICANE FORECAST FOR 2019" (PDF). Retrieved July 9, 2019.

- ^ a b "ATLANTIC BASIN SEASONAL HURRICANE FORECAST FOR 2019" (PDF). Retrieved August 5, 2019.

- ^ a b Mark Saunders; Adam Lea (August 6, 2019). "August Forecast Update for North Atlantic Hurricane Activity in 2019" (PDF). London, United Kingdom: Tropical Storm Risk.

- ^ a b "NOAA to issue updated 2019 Atlantic hurricane season outlook". Retrieved August 8, 2019.

- ^ Hurricane Specialist Unit (July 1, 2019). Monthly Tropical Weather Summary 800 AM EDT Mon Jul 1 2019 (Report). Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved November 10, 2019.

- ^ Hurricane Specialist Unit (August 1, 2019). Monthly Tropical Weather Summary 800 AM EDT Thu Aug 1 2019 (Report). Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved November 10, 2019.

- ^ Hurricane Specialist Unit (September 1, 2019). Monthly Tropical Weather Summary 800 AM EDT Sun Sep 1 2019 (Report). Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved November 10, 2019.

- ^ a b Hurricane Specialist Unit (October 1, 2019). Monthly Tropical Weather Summary 800 AM EDT Tue Oct 1 2019 (Report). Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved November 10, 2019.

- ^ Hurricane Specialist Unit (November 1, 2019). Monthly Tropical Weather Summary 800 AM EDT Fri Nov 1 2019 (Report). Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved November 10, 2019.

- ^ Andrew S. Latto (August 6, 2019). Tropical Cyclone Report: Subtropical Storm Andrea (PDF) (Report). Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved September 21, 2019.

- ^ weather.com meteorologists. "Potential Tropical Storm Barry to Impact Gulf Coast With Severe Flooding, Surge, Wind Threats; Hurricane Watch Issued". The Weather Channel. Web. Archived from the original on July 11, 2019. Retrieved July 11, 2019.

Computer forecast models for several days have shown that an upper-level disturbance meteorologists call a mesoscale convective vortex (MCV) originated in the Midwest last week, then moved from the Deep South into the northeastern Gulf of Mexico.

- ^ Eric S. Blake (July 6, 2019). "Graphical Tropical Weather Outlook". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved July 10, 2019.

- ^ weather.com meteorologists (July 11, 2019). "Potential Tropical Storm Barry to Impact Gulf Coast With Severe Flooding, Surge, Wind Threats; Hurricane Watch Issued". The Weather Channel. Web. Retrieved July 11, 2019.

Computer forecast models for several days have shown that an upper-level disturbance meteorologists call a mesoscale convective vortex (MCV) originated in the Midwest last week, then moved from the Deep South into the northeastern Gulf of Mexico.

- ^ Eric S. Blake (July 6, 2019). "Five-Day Graphical Tropical Weather Outlook". Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved July 10, 2019.

- ^ Stacy R. Stewart (July 9, 2019). "Five-Day Graphical Tropical Weather Outlook". Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved July 10, 2019.

- ^ Stacy R. Stewart (July 10, 2019). "Potential Tropical Cyclone Two Discussion Number 1". Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved July 10, 2019.

- ^ Jack Beven (July 11, 2019). Tropical Storm Barry Advisory Number 5 (Report). Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved July 11, 2019.

- ^ a b Beven, Jack (July 13, 2019). Hurricane Barry Discussion Number 13 (Report). Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved July 13, 2019.

- ^ Beven, Jack (July 13, 2019). Tropical Storm Barry Intermediate Advisory Number 13A (Report). Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved July 14, 2019.

- ^ Stewart, Stacy R. (July 14, 2019). Tropical Depression Barry Discussion Number 18 (Report). Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved July 15, 2019.

- ^ Burke, Patrick; Gallina, Gregg (July 15, 2019). Post-Tropical Cyclone Barry Advisory Number 22. www.wpc.ncep.noaa.gov (Report). Weather Prediction Center. Retrieved July 15, 2019.

- ^ Brann (July 17, 2019). Post-Tropical Cyclone Barry Advisory Number 30 (Report). Weather Prediction Center. Retrieved July 18, 2019.

- ^ "WPC surface analysis valid for 07/19/2019 at 06 UTC". NOAA's National Weather Service. July 19, 2019. Retrieved July 19, 2019.

- ^ a b Adams, Char (July 15, 2019). "Good Samaritans Form Human Chain to Rescue Swimmers from Rip Current in Florida". PEOPLE.com. Retrieved July 18, 2019.

- ^ a b Global Catastrophe Recap: July 2019 (PDF) (Report). AON. August 1, 2019. Retrieved August 16, 2019.

- ^ David A. Zelinsky (August 19, 2019). Tropical Cyclone Report: Tropical Depression Three (PDF) (Report). Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved August 22, 2019.

- ^ Robert J. Berg (October 25, 2019). Tropical Cyclone Report: Tropical Storm Chantal (PDF) (Report). Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved November 4, 2019.

- ^ "NHC Graphical Outlook Archive". www.nhc.noaa.gov. Retrieved August 24, 2019.

- ^ Stacy Stewart (August 24, 2019). Tropical Depression Five Discussion Number 1 (Report). National Hurricane Center. Retrieved August 24, 2019.

- ^ "Tropical Storm Dorian roars to life, takes aim at Caribbean". The Weather Network. Retrieved August 24, 2019.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ Duff, Renee (August 25, 2019). "Strengthening Tropical Storm Dorian to target Lesser Antilles early this week". AccuWeather. Retrieved August 25, 2019.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ Lixion A. Avila (August 28, 2019). "Hurricane Dorian Intermediate Advisory Number 17A". www.nhc.noaa.gov. Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved September 5, 2019.

- ^ Eric S. Blake (August 30, 2019). "Hurricane Dorian Advisory Number 23". www.nhc.noaa.gov. Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved September 5, 2019.

- ^ Miller, R.W.; Rice, D. (August 29, 2019). "Hurricane Dorian intensifies to Category 2, set to slam Florida as major storm on Labor Day". USA today. Retrieved August 30, 2019.

- ^ Miller, R.W. (August 30, 2019). "'Absolute monster' Hurricane Dorian strengthens to Category 4 'major' hurricane". USA today. Retrieved August 31, 2019.

- ^ "Hurricane Dorian Becomes the 5th Atlantic Category 5 in 4 Years". The Weather Channel. Retrieved September 2, 2019.

- ^ Lixion A. Avila (September 1, 2019). "Hurricane Dorian Advisory Number 33". www.nhc.noaa.gov. Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved September 1, 2019.

- ^ Lixion A. Avila (September 1, 2019). "Hurricane Dorian Discussion Number 34". www.nhc.noaa.gov. Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved September 1, 2019.

- ^ Andrew Latto (September 2, 2019). "Hurricane Dorian Tropical Cyclone Update". www.nhc.noaa.gov. Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved September 2, 2019.

- ^ Cowan, Levi (September 2, 2019). "Tropical Tidbits — [8am Monday] Dorian Stalling over Grand Bahama". Tropical Tidbits. Retrieved September 2, 2019.

- ^ Richard Pasch (September 2, 2019). "Hurricane Dorian Discussion Number 36". www.nhc.noaa.gov. National Hurricane Center. Retrieved September 5, 2019.

- ^ Daniel Brown (September 2, 2019). "Hurricane Dorian Discussion Number 38". www.nhc.noaa.gov. Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved September 5, 2019.

- ^ Daniel Brown (September 3, 2019). "Hurricane Dorian Discussion Number 41". www.nhc.noaa.gov. Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved September 5, 2019.

- ^ Lixion A. Avila (September 5, 2019). "Hurricane Dorian Discussion Number 47". www.nhc.noaa.gov. Miami, Florida. Retrieved September 5, 2019.

- ^ John Cangialosi (September 6, 2019). "Hurricane Dorian Discussion Number 52". www.nhc.noaa.gov. Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved September 10, 2019.

- ^ Eric S. Blake (September 6, 2019). "Hurricane Dorian Tropical Cyclone Update". www.nhc.noaa.gov. Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved September 10, 2019.

- ^ Jack Beven (September 7, 2019). "Hurricane Dorian Advisory Number 58". www.nhc.noaa.gov. Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved September 10, 2019.

- ^ Eric S. Blake; Lixion A. Avila (September 8, 2019). "Post-Tropical Cyclone Dorian Update". www.nhc.noaa.gov. Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved September 10, 2019.

- ^ Stacy R. Stewart (September 9, 2019). "Post-Tropical Cyclone Dorian Intermediate Advisory Number 63A". www.nhc.noaa.gov. Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved September 10, 2019.

- ^ Stacy R. Stewart (September 9, 2019). "Post-Tropical Cyclone Dorian Discussion Number 64". www.nhc.noaa.gov. Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved September 10, 2019.

- ^ a b "Hurricane Dorian Responsible for $3.4 Billion in Losses on Bahamas, Report Says". The Weather Channel. Associated Press. November 15, 2019. Retrieved December 9, 2019.

- ^ a b Russell, Khrisna (October 1, 2019). "Left In Limbo After Dorian". The Tribune. Retrieved October 4, 2019.

- ^ a b "Billion-Dollar Weather and Climate Disasters". National Centers for Environmental Information. 2019. Retrieved October 9, 2019.

- ^ a b "Hurricane Dorian Caused Over $100 Million in Insured Damage". Newswire. October 4, 2019. Retrieved October 4, 2019.

- ^ a b "Global Catastrophe Recap September 2019" (PDF). Aon Benfield. Retrieved October 10, 2019.

- ^ Eric S. Blake (November 15, 2019). Tropical Cyclone Report: Tropical Storm Erin (PDF) (Report). Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved November 24, 2019.

- ^ "Post-tropical storm Erin drenches parts of Nova Scotia, washes out road". CBC News. August 30, 2019. Retrieved August 30, 2019..

- ^ Canadian Press (August 30, 2019). "La tempête Erin a laissé jusqu'à 160 mm de pluie par endroits". Acadie Nouvelle (in French). Retrieved August 30, 2019..

- ^ Meteorological Service of Canada (2019). "Daily Data Report for August 2019: Summerside, PE". Environment Canada. Retrieved August 30, 2019.

- ^ Meteorological Service of Canada (2019). "Daily Data Report for August 2019: Chevery, Qc". Environment Canada. Retrieved August 30, 2019..

- ^ "NHC Graphical Outlook Archive". www.nhc.noaa.gov. Retrieved September 3, 2019.

- ^ "NHC Graphical Outlook Archive". www.nhc.noaa.gov. Retrieved September 3, 2019.

- ^ "NHC Graphical Outlook Archive". www.nhc.noaa.gov. Retrieved September 3, 2019.

- ^ "Tropical Depression SEVEN". www.nhc.noaa.gov. Retrieved September 3, 2019.

- ^ "Tropical Storm FERNAND". www.nhc.noaa.gov. Retrieved September 3, 2019.

- ^ "Tropical Storm Fernand Tropical Cyclone Update...Corrected". www.nhc.noaa.gov. Retrieved September 9, 2019.

- ^ "Remnants of FERNAND". www.nhc.noaa.gov. Retrieved September 6, 2019.

- ^ a b "Minuto a minuto: Fernand azota Monterrey con lluvias torrenciales y deja un muerto". Infobae. September 4, 2019. Retrieved September 7, 2019.

- ^ a b "Fernand deja daños por 4 mil 200 mdp". Pulso Político. September 11, 2019. Retrieved September 12, 2019.

- ^ John Beven (August 30, 2019). "Five-Day Graphical Tropical Weather Outlook". www.nhc.noaa.gov. Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved September 3, 2019.

- ^ Eric S. Blake (September 3, 2019). "Tropical Depression Eight Discussion Number 1". www.nhc.noaa.gov. Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved September 2, 2019.

- ^ Stacy R. Stewart (September 4, 2019). "Tropical Storm Gabrielle Discussion Number 3". www.nhc.noaa.gov. Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved September 16, 2019.

- ^ Arthur Taylor; Eric S. Blake (September 9, 2019). "Tropical Storm Gabrielle Discussion Number 26". www.nhc.noaa.gov. Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved September 10, 2019.

- ^ David Hamrick; Eric S. Blake (September 10, 2019). "Post-Tropical Cyclone Gabrielle Discussion Number 29". www.nhc.noaa.gov. National Hurricane Center. Retrieved September 12, 2019.

- ^ Eric S. Blake (September 8, 2019). "Two-Day Graphical Tropical Weather Outlook". www.nhc.noaa.gov. Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved September 15, 2019.

- ^ Lixion A. Avila (September 11, 2019). "Two-Day Graphical Tropical Weather Outlook". www.nhc.noaa.gov. Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved September 15, 2019.

- ^ Lixion A. Avila (September 12, 2019). "Two-Day Graphical Tropical Weather Outlook". www.nhc.noaa.gov. Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved September 15, 2019.

- ^ Lixion Avila (September 12, 2019). "Potential Tropical Cyclone Nine Discussion Number 1". www.nhc.noaa.gov. Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved September 12, 2019.

- ^ Lixion Avila (September 13, 2019). "Tropical Depression Nine Discussion Number 5". Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved September 13, 2019.

- ^ John Cangialosi (September 13, 2019). "Tropical Storm Humberto Discussion Number 6". Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved September 14, 2019.

- ^ Lixion A. Avila (September 14, 2019). "Tropical Storm Humberto Discussion Number 9". www.nhc.noaa.gov. Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved September 16, 2019.

- ^ Richard Pasch (September 16, 2019). "Hurricane Humberto Discussion Number 14". www.nhc.noaa.gov. Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved September 16, 2019.

- ^ Richard Pasch (September 18, 2019). "Hurricane Humberto Advisory Number 21A". www.nhc.noaa.gov. Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved September 19, 2019.

- ^ "Post-Tropical Cyclone HUMBERTO". www.nhc.noaa.gov. Retrieved September 21, 2019.

- ^ Arthur Taylor; Eric S. Blake (September 9, 2019). "Five-Day Graphical Tropical Weather Outlook". www.nhc.noaa.gov. Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved September 18, 2019.

- ^ Stacy R. Stewart (September 16, 2019). "Two-Day Graphical Tropical Weather Ourlook". www.nhc.noaa.gov. Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved September 18, 2019.

- ^ Daniel Brown (September 17, 2019). "Tropical Depression Ten Discussion Number 1". www.nhc.noaa.gov. Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved September 18, 2019.

- ^ Dave Roberts (September 18, 2019). "Tropical Storm Jerry Discussion Number 4". www.nhc.noaa.gov. Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved September 19, 2019.

- ^ "Hurricane JERRY". www.nhc.noaa.gov. Retrieved September 20, 2019.

- ^ "Tropical Storm JERRY". www.nhc.noaa.gov. Retrieved September 21, 2019.

- ^ Jack Beven (September 14, 2019). "Two-Day Graphical Tropical Weather Outlook". www.nhc.noaa.gov. Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved September 19, 2019.

- ^ Stacy R. Stewart (September 17, 2019). "Two=Day Graphical Tropical Weather Outlook". www.nhc.noaa.gov. Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved September 17, 2019.

- ^ Daniel Brown (September 17, 2019). "Tropical Depression Eleven Special Discussion Number 1". www.nhc.noaa.gov. Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved September 17, 2019.

- ^ Michael Brennan; Daniel Brown (September 17, 2019). "Tropical Storm Imelda Tropical Cyclone Update". www.nhc.noaa.gov. Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved September 19, 2019.

- ^ David Zelinsky; Daniel Brown (September 17, 2019). "Tropical Storm Imelda Tropical Cyclone Update". www.nhc.noaa.gov. Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved September 19, 2019.

- ^ Richard Pasch (September 18, 2019). "Tropical Depression Imelda Discussion Number 3". www.nhc.noaa.gov. Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved September 19, 2019.

- ^ Brian Kahn (September 19, 2019). "Tropical Depression Imelda Has Dumped More Than 40 Inches of Rain on the Texas Gulf Coast". earther.gizmodo.com. Gizmodo. Retrieved September 19, 2019.

- ^ a b "2010-2019: A landmark decade of U.S. billion-dollar weather and climate disasters". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved January 8, 2020.

- ^ "NHC Graphical Outlook Archive". www.nhc.noaa.gov. Retrieved September 22, 2019.

- ^ Stacy Stewart (September 22, 2019). Tropical Storm Karen Discussion Number 1 (Report). National Hurricane Center. Retrieved September 22, 2019.

- ^ "Tropical Depression KAREN". www.nhc.noaa.gov. Retrieved September 24, 2019.

- ^ "Tropical Storm KAREN". www.nhc.noaa.gov. Retrieved September 24, 2019.

- ^ Camille Moreno (September 22, 2019). "TT under warning for Tropical Storm Karen". Newsday. Retrieved September 22, 2019.

- ^ Julie Celestial (September 23, 2019). "Severe flooding hits Trinidad and Tobago, Karen heading toward Puerto Rico and Virgin Islands". The Watchers. Retrieved September 28, 2019.

- ^ Ron Brackett (September 22, 2019). "Tropical Storm Karen Floods Streets, Traps People in Homes in Tobago". The Weather Channel. TWC Product and Technology LLC. Retrieved September 22, 2019.

- ^ Carolyn Kissoon (September 22, 2019). "NO SCHOOL ON MONDAY". Trinidad Express. Trinidad Express Newspapers. Retrieved September 22, 2019.

- ^ "Tormenta Tropical Karen provocó inundaciones en Caracas y La Guaira". Descifrado. September 22, 2019. Retrieved September 22, 2019.

- ^ Richard Tribou (September 22, 2019). "Tropical Storm Karen forms, watches issued for Puerto Rico, Virgin Islands". Orlando Sentinel. Orlando, Florida. Retrieved September 22, 2019.

- ^ a b Ron Brackett; Jan Wesner Childs (September 25, 2019). "Tropical Storm Karen Causes Landslides, Power Outages in Puerto Rico, U.S. Virgin Islands". The Weather Channel. TWC Product and Technology LLC. Retrieved September 25, 2019.

- ^ Travis Fedschun (September 24, 2019). "Tropical systems menace Puerto Rico, Bermuda as Lorenzo forecast to become 'large and powerful' hurricane". Fox News. FOX News Network, LLC. Retrieved September 24, 2019.

- ^ Staff (September 25, 2019). "Tropical Storm Karen dumps heavy rain over Puerto Rico as storm moves slowly north". CBS News. CBS Interactive Inc. Retrieved September 25, 2019.

- ^ Eric S. Blake (September 22, 2019). "Five-Day Graphical Tropical Weather Outlook". www.nhc.noaa.gov. Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved September 28, 2019.

- ^ a b c d e f g h David A. Zelinsky (December 16, 2019). "Tropical Cyclone Report: Hurricane Lorenzo" (PDF). National Hurricane Center. NOAA. Retrieved December 17, 2019.

- ^ "BOURBON: Press release - Update on search operations for Bourbon Rhode". GlobeNewswire. September 28, 2019. Retrieved September 28, 2019.

- ^ "Bourbon Rhode: Fourth Body Recovered". The Maritime Executive. Retrieved October 3, 2019.

- ^ Price, Mark; Fowler, Hayley (October 3, 2019). "Four swimmers have died off the North Carolina coast since Monday". Charlotte Observer. Retrieved October 4, 2019.

- ^ Moynihan, Ellen; Tracy, Thomas (October 11, 2019). "Body of second teen who went missing in waters off the Rockaways recovered: officials". New York Daily News. Retrieved October 12, 2019.

- ^ Latto, Andrew (October 10, 2019). "Atlantic Tropical Weather Outlook (12Z)". National Hurricane Center. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Archived from the original on October 10, 2019. Retrieved October 12, 2019.

- ^ Latto, Andrew (October 10, 2019). "Atlantic Tropical Weather Outlook (18Z)". National Hurricane Center. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Archived from the original on October 10, 2019. Retrieved October 12, 2019.

- ^ Latto, Andrew (October 11, 2019). "Special Atlantic Tropical Weather Outlook (1230Z)". National Hurricane Center. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Archived from the original on October 11, 2019. Retrieved October 12, 2019.

- ^ Latto, Andrew (October 11, 2019). "Subtropical Storm Melissa Discussion #1 (15Z)". National Hurricane Center. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Archived from the original on October 11, 2019. Retrieved October 12, 2019.

- ^ Latto, Andrew (October 12, 2019). "Tropical Storm Melissa Advisory Number 6". National Hurricane Center. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved October 12, 2019.

{{cite web}}: Check|archive-url=value (help)CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ "Crisfield, Salisbury Officials Close Off Some Streets Due to Tidal Flooding". Salisbury, MD: WBOC-TV. October 11, 2019. Retrieved October 11, 2019.

- ^ Metzner, Mallory (October 11, 2019). "Nor'easter Causes Bethany Beach Erosion". Salisbury, MD: WBOC-TV. Retrieved October 11, 2019.

- ^ Tracy, Spencer (October 11, 2019). "Coastal Flooding Impacts Dewey Beach". Salisbury, MD: WBOC-TV. Retrieved October 11, 2019.

- ^ Scott, Katherine (October 11, 2019). "Storm off the coast causes flooding at Jersey Shore". Philadelphia, PA: WPVI-TV. Retrieved October 11, 2019.

- ^ Lixion A. Avila (November 1, 2019). Tropical Cyclone Report: Tropical Depression Fifteen (PDF) (Report). Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved November 3, 2019.

- ^ Robbie Berg (October 10, 2019). Five-Day Graphical Tropical Weather Outlook (Report). Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved November 19, 2019.

- ^ Dave Roberts (October 16, 2019). Five-Day Graphical Tropical Weather Outlook (Report). Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved November 19, 2019.

- ^ John Beven (October 17, 2019). Potential Tropical Cyclone Sixteen Discussion Number 1 (Report). Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved November 19, 2019.

- ^ Michael Brennan (October 18, 2019). POTENTIAL TROPICAL CYCLONE SIXTEEN FORECAST/ADVISORY NUMBER 5 (Report). Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved November 19, 2019.

- ^ "Tropical Storm NESTOR". www.nhc.noaa.gov. Retrieved October 18, 2019.

- ^ Stacy Stewart (October 19, 2019). Post-Tropical Cyclone Nestor Discussion Number 10 (Report). Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved November 19, 2019.

- ^ Tribou, Richard. "Tropical Storm Nestor loses tropical status as it nears Florida landfall, lashing state with storm clusters, tornado threats". Orlando Sentinel. Retrieved October 19, 2019.

- ^ Castro, Amanda (October 19, 2019). "Tropical Storm Nestor causes damage across state". WKMG. Retrieved October 19, 2019.