Boeing 737 MAX groundings

A parking lot at Boeing Field in Seattle, Washington, filled with undelivered Boeing 737 MAX aircraft | |

| Date |

|

|---|---|

| Duration |

|

| Cause | Airworthiness revoked after recurring flight control failure |

| Deaths | 346:

|

Parts of this article (those related to House of Representatives final report) need to be updated. (September 2020) |

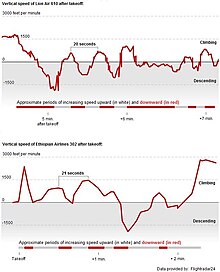

In March 2019, the Boeing 737 MAX passenger airliner was grounded worldwide after 346 people died in two crashes, Lion Air Flight 610 on October 29, 2018 and Ethiopian Airlines Flight 302 on March 10, 2019. Ethiopian Airlines immediately grounded its remaining MAX fleet. On March 11, the Civil Aviation Administration of China ordered the first nationwide grounding, followed by most other aviation authorities in quick succession. The U.S. Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) publicly affirmed the airworthiness of the airplane on March 11, but grounded it on March 13 after receiving evidence of accident similarities. All 387 aircraft, which served 8,600 flights per week for 59 airlines, were banned from service by March 18, 2019.

In November 2018, Boeing revealed the MAX had a new automated flight control, the Maneuvering Characteristics Augmentation System (MCAS), that could repeatedly push the airplane nose down. Boeing had omitted any mention of the system in the aircraft manuals. A week after the first accident, Boeing and the FAA sent airlines urgent messages emphasizing a procedure to recover from a malfunction. In a presentation to the FAA, Boeing deflected blame and continued to assert that appropriate crew action would save the aircraft.[1] Before the second accident, the FAA anticipated that Boeing would deliver a software update to MCAS by April 2019.[2][3]

During the groundings, the U.S. Congress, Transportation Department, FBI and ad hoc panels investigated the FAA certification of the MAX. The Indonesian NTSC accident report faulted aircraft certification, maintenance, and flight crew actions. The Ethiopian ECAA determined that the flight crew had attempted the recovery procedure. The U.S. NTSB said Boeing failed to assess the consequences of MCAS failure and made incorrect assumptions about flight crew response. The U.S. Inspector General said Boeing deliberately misrepresented MCAS to avoid scrutiny. The FAA revoked Boeing's authority to issue airworthiness certificates for individual MAX airplanes and imposed a fine on Boeing for exerting "undue pressure" on its designated aircraft inspectors. The House of Representatives faulted engineering flaws, mismanagement, cover-up, and oversight lapses rooting from the FAA's delegation of authority to Boeing.[4]

In January 2020, with 400 aircraft awaiting certification and delivery, Boeing suspended production of the MAX until May 2020. By March 2020, the grounding had cost Boeing $18.6 billion in compensation to airlines and victims' families, lost business, and legal fees. Airlines and leasing companies that once struggled without the MAX had cancelled nearly 800 orders of the MAX by September 2020, months into the COVID-19 pandemic. On July 1, Boeing completed several days of certification flights. In August, the FAA published details of changes related to aircraft defects and pilot training to be mandated before the MAX returns to service. On November 18, 2020, the FAA cleared the MAX to return to service, ending a 20 month flight ban, the longest ever for a U.S. airline. On December 9, 2020, Brazilian airline Gol became the first airline to use the plane in regular service since the 2018 ban.[5][6]

Timeline

2018

- October 29, a 737 MAX 8 operating Lion Air Flight 610 crashed after take-off from Jakarta, killing all 189 on-board.

- November 6, Boeing issued a service bulletin warning that with "erroneous AoA data, the pitch trim system can trim the stabilizer nose down in increments lasting up to 10 seconds" which "can be stopped and reversed with the use of the electric stabilizer trim switches but may restart 5 seconds after" and instructed pilots to counteract it by running the Runaway stabilizer and manual trim procedure.[7]

- November 7, the FAA issued an Emergency airworthiness directive requiring revising "the AFM to provide the flight crew with runaway horizontal stabilizer trim procedures" when "repeated nose-down trim commands" are caused by "an erroneously high single AoA sensor".[7]

- November 10, Boeing referred to MCAS in multi-operator messages.[8] The automated flight control could cause unintended nosedives, but was omitted from crew manuals and training.[9]

- November 27, the Allied Pilots Association of American Airlines had a meeting with Boeing to express concerns with the MCAS effectiveness, and was unnerved by the airframer's responses.[10]

- December 3, the FAA conducted an unpublished "Transport Aircraft Risk Assessment Methodology” (TARAM) analysis that concluded, "if left uncorrected, the MCAS design flaw in the 737 MAX could result in as many as 15 future fatal crashes over the life of the fleet”; it was exposed by the United States House Committee on Transportation and Infrastructure on December 11, 2019.[11]

2019

- March 10, another 737 MAX 8 operating Ethiopian Airlines Flight 302 crashed shortly after take-off from Addis Ababa airport, killing all 157 on-board, due to a similar faulty MCAS, initiating a worldwide flight ban for the aircraft, starting with China.

- March 13, the U.S. FAA was among the last to order the grounding of the 737 MAX, after claiming there was no reason: China had the most aircraft in service, 96, followed by the U.S. with 72, Canada with 39 and India with 21.

- March 20, EASA and Transport Canada indicated that they would conduct their own reviews of Boeing's proposed software update.[12]

- March 27, Boeing unveiled a software update to avoid MCAS errors, already developed and tested it in-flight, to be certified.

- April 5, Boeing announced it was cutting 737 production by almost a fifth, to 42 aircraft monthly, anticipating a prolonged grounding, and had formed an internal design review committee.

- May 13, Republican Congressman Sam Graves at the House Aviation subcommittee hearing, blamed the 737 MAX crashes on poor training of the Indonesian and Ethiopian pilots; he stated that "pilots trained in the U.S. would have been successful" in handling the emergencies on both jets.[13][14]

- June 18, IAG signed a letter of intent for 200 737 MAXs at the Paris air show, followed by Turkish SunExpress and Air Astana later in the year.

- June 26, flight tests for the FAA uncovered a data processing issue affecting the pilots' ability to perform the "runaway stabiliser" procedure to respond to MCAS errors.

- October 30, Boeing CEO Dennis Muilenburg testified before U.S. Congress committees, defending Boeing's safety culture and denying knowledge of internal messages in which Boeing's former chief technical pilot said he had unknowingly lied to regulators, and voiced its concerns on MCAS.

- November 22, Boeing unveiled the first 737 MAX 10 flight-test aircraft.[9]

- November 26, the FAA revoked Boeing's Organization Designation Authorization to issue airworthiness certificates for individual MAX airplanes.[15]

- December 17, Boeing confirmed the suspension of 737 MAX production from January 2020.

- December 23, Dennis Muilenburg resigned, to be replaced by board chairman David Calhoun.[9]

2020

- January 7, Boeing recommended "simulator training in addition to computer based training".[16]

- January 9, Boeing released previous messages in which it claimed no flight simulator time was needed for pilots, and distanced itself from emails mocking airlines and the FAA, and criticising the 737 MAX design.

- January 13, David Calhoun became CEO, pledging to improve Boeing’s commitment to safety and transparency, and estimating the return to service in mid-2020.

- January 21, Boeing estimated the ungrounding could begin in mid-2020.[9]

- May 27, Boeing resumed production of the MAX at a "very gradual pace".[17]

- June 28 to July 1, the FAA conducted flight tests with a view to recertification of the 737 MAX.[18]

- September 16, the U.S. House of Representatives releases its concluding report, blaming Boeing and the FAA for lapses in the design, construction and certification.[19]

- September 30, a Boeing 737 MAX test aircraft was flown by FAA administrator Stephen Dickson.[20]

- October 16, Patrick Ky, the executive director of the European Union Aviation Safety Agency, claimed that the updated 737 Max reached the level of safety "high enough" for EASA.[21]

- November 18, the FAA announced that the MAX had been cleared to return to service in U.S. airspace. Airlines must make maintenance and system updates before flights can resume. Airline training programs will also require approval. The MAX is subject to separate approvals in other nations where it operates.[6][22]

- December 9, Brazilian low-cost carrier Gol Transportes Aéreos was the first airline to resume passenger service, before American Airlines on December 29.[23]

Groundings

After the Ethiopian Airlines crash, China and most other civil aviation authorities grounded the airliner over safety concerns. Other jurisdictions, including the U.S., followed suit as new evidence revealed similarities between both crashes. The groundings were ordered despite Boeing CEO Dennis Muilenburg's public assurances that the airplane was safe and a phone conversation with President Trump in which he "reiterated to the President our position that the MAX aircraft is safe", according to a Boeing statement.[24] In response to increasing domestic and international pressure to take action,[25][26][27] the U.S. Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) grounded the aircraft on March 13, 2019, reversing a Continued Airworthiness Notice issued two days prior.[28] About 30 MAX aircraft were flying in U.S. airspace at the time and were allowed to reach their destinations.[29] By March 18, every single Boeing 737 MAX plane (387 in total) had been grounded, which affected 8,600 weekly flights operated by 59 airlines across the globe.[30] Several ferry flights were operated with flaps extended to circumvent MCAS activation.

Accident investigations

Lion Air Flight 610

Preliminary investigations revealed serious flight control problems that traumatized passengers and crew on the aircraft's previous flight, as well as signs of angle-of-attack (AoA) sensor and other instrument failures on that and previous flights, tied to a design flaw involving the Maneuvering Characteristics Augmentation System (MCAS) of the 737 MAX series. The aircraft maintenance records indicated that the AoA Sensor was just replaced before the accident flight.[31] The report tentatively attributed the accident to the erroneous angle-of-attack (AoA) data and automatic nose-down trim commanded by MCAS.[32][33]

The NTSC final report, published on October 23, 2019 was prepared with assistance from the U.S. NTSB. NTSC's investigator Nurcahyo Utomo identified nine factors to the accident, saying:

"The nine factors are the root problem; they cannot be separated. Not one is contributing more than the other. Unlike NTSB reports that identify the primary cause of accidents and then list contributing issues determined to be less significant, Indonesia is following a convention used by many foreign regulators of listing causal factors without ranking them".[34][35][36]

The final report has been shared with families of Lion Air Flight 610, then published on October 25, 2019.[37][38][39][40]

Ethiopian Airlines Flight 302

The initial reports for Flight 302 found that the pilots struggled to control the airplane in a manner similar to the Lion Air flight 610 crash.[41] On March 13, 2019, the FAA announced that evidence from the crash site and satellite data on Flight 302 suggested that it might have suffered from the same problem as Lion Air Flight 610 in that the jackscrew controlling the pitch of the horizontal stabilizer of the crashed Flight 302, was found to be set in the full "nose down" position, similar to Lion Air Flight 610.[42] This further implicated MCAS as contributory to the crash.[43][44][45]

Ethiopian Airlines spokesman Biniyam Demssie said that the procedures for disabling MCAS had just been incorporated into pilot training. "All the pilots flying the MAX received the training after the Indonesia crash," he said. "There was a directive by Boeing, so they took that training."[46] Despite following the procedure, the pilots could not recover.[47]

The Ethiopian Civil Aviation Authority (ECAA) is leading investigations for Flight 302. The United States Federal Aviation Administration will also assist in the investigation.[48] Both the cockpit voice recorder and the flight data recorder were recovered from the crash site on March 11, 2019.[49] The French aviation accident investigation agency BEA announced that it would analyze the flight recorders from the flight.[50] BEA received the flight recorders on March 14, 2019.[51]

On March 17, 2019, the Ethiopia's transport minister Dagmawit Moges announced that the black box had been found and downloaded, and that the preliminary data retrieved from the flight data recorder show a "clear similarity" with those of Lion Air Flight 610 which crashed off Indonesia.[52][53][54] Due to this finding, some experts in Indonesia suggested that the NTSC should cooperate with Flight 302's investigation team.[55] Later on the evening, the NTSC offered assistance to Flight 302's investigation team, stating that the committee and the Indonesian Transportation Ministry would send investigators and representatives from the government to assist with the investigation of the crash.[56]

The Ethiopian Civil Aviation Authority published an interim report on March 9, 2020, one day before the March 10 anniversary of the crash.[57] Investigators have tentatively concluded that the crash was caused by the aircraft's design.[58][59]

United States

On November 6, 2018, four days before it identified MCAS by name, Boeing published a supplementary service bulletin prompted by the first crash. The bulletin describes warnings triggered by erroneous AoA data, and referred pilots to a "non-normal runaway trim" procedure as resolution, specifying a narrow window of a few seconds before the system would reactivate and pitch the nose down again.[60] The FAA issued an emergency airworthiness directive, 2018-23-51, on November 7, 2018 requiring the bulletin's inclusion in the flight manuals, and that pilots immediately review the new information provided.[61][62] On March 11, FAA defended the aircraft against groundings citing these emergency procedures (Continued Airworthiness Notification to the International Community) for operators.

In December 2018, a month after the Lion Air accident, the FAA had conducted an internal safety risk analysis predicted fifteen more crashes with no repairs to MCAS, but that report was not revealed until the U.S. House hearing in December 2019. FAA's administrator, Stephen Dickson, who assumed the position during the accident investigations, said in retrospect that the accident risk was unsatisfactory.

On September 26, 2019, the NTSB released the results of its review of potential lapses in the design and approval of the 737 MAX.[63][64]: 1 [65] The NTSB report concludes that assumptions "that Boeing used in its functional hazard assessment of uncommanded MCAS function for the 737 MAX did not adequately consider and account for the impact that multiple flight deck alerts and indications could have on pilots' responses to the hazard". When Boeing induced a stabilizer trim input that simulated the stabilizer moving consistent with the MCAS function, "... the specific failure modes that could lead to unintended MCAS activation (such as an erroneous high AOA input to the MCAS) were not simulated as part of these functional hazard assessment validation tests. As a result, additional flight deck effects (such as IAS DISAGREE and ALT DISAGREE alerts and stick shaker activation) resulting from the same underlying failure (for example, erroneous AOA) were not simulated and were not in the stabilizer trim safety assessment report reviewed by the NTSB."[64][66]

The NTSB questioned the long-held industry and FAA practice of assuming the nearly instantaneous responses of highly trained test pilots as opposed to pilots of all levels of experience to verify human factors in aircraft safety.[67] The NTSB expressed concerns that the process used to evaluate the original design needs improvement because that process is still in use to certify current and future aircraft and system designs. The FAA could for example randomly sample pools from the worldwide pilot community to get a more representative assessment of cockpit situations.[68]

Responsible states

ICAO regulations Annex 13, “Aircraft Accident and Incident Investigation”, defines which states may participate in investigations. For the two MAX accidents these are:[69]

- Indonesia, for Lion Air Flight 610 as state of registration, state of occurrence and state of operator.

- Ethiopia, for Ethiopian Airlines Flight 302, as state of registration, state of occurrence and state of operator.

- The United States, as state of manufacturer and issuer of the type certificate.

The participating state or national transportation safety bureaus are the NTSB for the US and the NTSC for Indonesia. Australia and Singapore also offered technical assistance, shortly after the Lion Air accident, regarding data recovery from the new generation flight recorders (FDR). With the exception of Ethiopia, the officially recognised countries are members of the Joint Authorities Technical Review (JATR).

Type certification and return to service

Investigations into both crashes determined that Boeing and the FAA favored cost-saving solutions, which ultimately produced a flawed design of the MCAS instead.[70] The FAA's Organization Designation Authorization program, allowing manufacturers to act on its behalf, was also questioned for weakening its oversight of Boeing.

Boeing wanted the FAA to certify the airplane as another version of the long-established 737; this would limit the need for additional training of pilots, a major cost saving for airline customers. During flight tests, however, Boeing discovered that the position and larger size of the engines tended to push up the airplane nose during certain maneuvers. To counter that tendency and ensure fleet commonality with the 737 family, Boeing added MCAS so the MAX would handle similar to earlier 737 versions. Boeing convinced the FAA that MCAS could not fail hazardously or catastrophically, and that existing procedures were effective in dealing with malfunctions.[citation needed] The MAX was exempted from certain newer safety requirements, saving Boeing billions of dollars in development costs.[71] In February 2020, the US Justice Department (DOJ) investigated Boeing's hiding of information from the FAA, based on the content of internal emails.[72] In January 2021, Boeing settled to pay over $2.5 billion after being charged with fraud in connections to the crashes. The settlement included $243.6 million criminal fine for defrauding the FAA when it won the approval for the 737 MAX, $1.77 billion as compensation for airline customers, and $500 million as compensation for family members of crash victims.[73]

In June 2020, the U.S. Inspector General's report revealed that MCAS problems dated several years before the accidents.[74] The FAA found several defects that Boeing deferred to fix, in violation of regulations.[75] In September 2020, the House of Representatives concluded its investigation and cited numerous instances where Boeing dismissed employee concerns with MCAS, prioritized deadline and budget constraints over safety, and where it lacked transparency in disclosing essential information to the FAA. It further found that the assumption that simulator training would not be necessary had "diminished safety, minimized the value of pilot training, and inhibited technical design improvements".[7]

In November 2020, the FAA announced that it had cleared the 737 MAX to return to service.[6] Various system, maintenance and training requirements are stipulated, as well as design changes that must be implemented on each aircraft before the FAA issues an airworthiness certificate, without delegation to Boeing. Other major regulators worldwide are gradually following suit: In 2021, after two years of grounding, Transport Canada and EASA both cleared the MAX subject to additional requirements.[76][77]

Maneuvering Characteristics Augmentation System

The Maneuvering Characteristics Augmentation System (MCAS) is a flight stabilizing feature developed by Boeing that became notorious for its role in two fatal accidents of the 737 MAX in 2018 and 2019, which killed all 346 passengers and crew among both flights.

Because the CFM International LEAP engine used on the 737 MAX was larger and mounted further forward from the wing and higher off the ground than on previous generations of the 737, Boeing discovered that the aircraft had a tendency to push the nose up when operating in a specific portion of the flight envelope (flaps up, high angle of attack, manual flight). MCAS was intended to mimic the flight behavior of the previous Boeing 737 Next Generation. The company indicated that this change eliminated the need for pilots to have simulator training on the new aircraft.[citation needed]

After the fatal crash of Lion Air Flight 610 in 2018, Boeing and the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) referred pilots to a revised trim runaway checklist that must be performed in case of a malfunction. Boeing then received many requests for more information and revealed the existence of MCAS in another message, and that it could intervene without pilot input.[78][79] According to Boeing, MCAS was implemented to compensate for an excessive angle of attack by adjusting the horizontal stabilizer before the aircraft would potentially stall. Boeing denied that MCAS was an anti-stall system, and stressed that it was intended to improve the handling of the aircraft while operating in a specific portion of the flight envelope. Following the crash of Ethiopian Airlines Flight 302 in 2019, Ethiopian authorities stated that the procedure did not enable the crew to prevent the accident, however further investigation revealed that the pilots did not follow the procedure properly.[80] The Civil Aviation Administration of China then ordered the grounding of all 737 MAX planes in China, which led to more groundings across the globe.

Boeing admitted MCAS played a role in both accidents, when it acted on false data from a single angle of attack (AoA) sensor. In 2020, the FAA, Transport Canada, and European Union Aviation Safety Agency (EASA) evaluated flight test results with MCAS disabled, and suggested that the MAX might not have needed MCAS to conform to certification standards.[81] Later that year, an FAA Airworthiness Directive[82] approved design changes for each MAX aircraft, which would prevent MCAS activation unless both AoA sensors register similar readings, eliminate MCAS's ability to repeatedly activate, and allow pilots to override the system if necessary. The FAA began requiring all MAX pilots to undergo MCAS-related training in flight simulators by 2021.

Reactions

Boeing expressed its sympathy to the relatives of the Lion Air Flight 610 and Ethiopian Airlines Flight 302 crash victims, while simultaneously defending the aircraft against any faults and suggesting the pilots had insufficient training, until rebutted by evidence. After the 737 MAX fleet was globally grounded, starting in China with the Civil Aviation Administration of China the day after the second crash,[83] Boeing provided several outdated return-to-service timelines, the earliest of which was "in the coming weeks" after the second crash. On October 11, 2019, David L. Calhoun replaced Dennis Muilenburg as chairman of Boeing, then succeeded Muilenburg's role as chief executive officer in January 2020.

One year after the crashes, lawmakers demanded answers from then-CEO Dennis Muilenburg in a hearing on Capitol Hill. They questioned him about the discovered mistakes leading to the crashes and also about Boeing's subsequent cover-up efforts. One important line of enquiry was how Boeing "tricked" regulators into approving sub-standard pilot training materials, especially the deletion of mentioning the critical flight stabilization system MCAS.[84] A Texas court ruled in October 2022 that the passengers killed in two 737 MAX crashes are legally considered "crime victims", which has consequences concerning possible remedies.

Airbus articulated that the crashes had been a tragedy and that it would never be good for any competitor to see a particular aircraft type having problems. Airbus reiterated that the 737 MAX grounding and backlog would not change the production volume of the competing Airbus A320neo family as these aircraft had already been sold out through 2025 and logistical and supplier capacities could not be easily enhanced short to medium term in this industry.

Pilots' and flight attendants' opinions were mixed, with some expressing confidence in the certification renewal, while others were increasingly disappointed that Boeing had knowingly concealed the existence and the risks of the newly introduced flight stabilization system MCAS to the 737 series as more and more internal information about the development and certification process came to light. Retired pilot Chesley Sullenberger criticized the aircraft design and certification processes and reasoned that relationship between the industry and its regulators had been too "cozy".

Financial and economic effects

The Boeing 737 MAX groundings has had a deep financial effect on the aviation industry and a significant effect on the national economy of the United States. No airline took delivery of the MAX during the groundings. Boeing slowed MAX production to 42 aircraft per month until January 2020, when they halted until the aircraft was reapproved by regulators. Boeing has suffered directly through increased costs, loss of sales and revenue, loss of reputation, victims litigation, client compensation, decreased credit rating and lowered stock value. In January 2020, the company estimated a loss of $18.4 billion for 2019, and it reported 183 canceled MAX orders for the year.

In February 2020, the global COVID-19 pandemic and the resulting travel bans created further uncertainty for Boeing. In March 2020, news that Boeing was seeking a $60 billion bailout caused a steep drop in its stock price, though Boeing eventually received $17 billion in funds from the coronavirus stimulus.[85] Its extensive supply chain providing aircraft components and flight simulators suffered similar losses, as did the aircraft services industry, including crew training, the aftermarket and the aviation insurance industry. At the time of the recertification by the FAA in November 2020, Boeing's net orders for the 737 MAX were down by more than 1,000 aircraft,[86] 448 orders canceled and 782 orders removed from the backlog because they are no longer certain enough to rely on; the total estimated direct costs of the MAX groundings were US$20 billion and indirect costs over US$60 billion.[87] On January 7, 2021, Boeing settled to pay over $2.5 billion after being charged with fraud.

See also

- Qantas Flight 72: data failure causing pitch down, severely injuring passengers

- Air France Flight 447: fatal accident following data and pitot tube failure and autopilot disablement

- Turkish Airlines Flight 1951: Dutch authorities have reopened the accident probe into this 2009 accident involving the prior generation 737-800 series aircraft.[88]

- Boeing 787 Dreamliner battery fires: the aircraft was grounded in 2013 for modifications to mitigate or contain risk of inflight fire.

References

- ^ "After Lion Air crash, Boeing doubled down on faulty 737 MAX assumptions". The Seattle Times. November 8, 2019. Retrieved October 3, 2020.

- ^ "Continued Airworthiness Notification to the International Community" (PDF). FAA. March 11, 2019. Retrieved March 19, 2019.

- ^ "Exclusive: Boeing kept FAA in the dark on key 737 MAX design changes - U.S. IG report". Reuters. July 1, 2020. Retrieved July 5, 2020.

- ^ Chokshi, Niraj (September 16, 2020). "House Report Condemns Boeing and F.A.A. in 737 Max Disasters". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved September 20, 2020.

- ^ CNN, Thom Patterson. "Airplane groundings are rare. Here are some of history's biggest". CNN. Retrieved November 20, 2020.

{{cite web}}:|last=has generic name (help) - ^ a b c Gates, Dominic (November 18, 2020). "Boeing 737 MAX can return to the skies, FAA says". Cite error: The named reference "SeattleTimesUngrounding" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ a b c "Boeing nearing 737 Max fleet bulletin on AoA warning after Lion Air crash". The Air Current. November 7, 2018. Retrieved July 5, 2020. Cite error: The named reference ":0" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ Hradecky, Simon (January 14, 2019). "Crash: Lion B38M near Jakarta on Oct 29th 2018, aircraft lost height and crashed into Java Sea, wrong AoA data". The Aviation Herald.

On Nov 10th 2018 Boeing sent out multi-operator messages informing operators about the MCAS

- ^ a b c d Graham Dunn (March 13, 2020). "Timeline of the twists and turns in the grounding of the Boeing 737 Max". Flightglobal.

- ^ "Pilot Union President to Call for Accountability from Boeing and Reassessment of FAA Certification Process" (Press release). Allied Pilots Association. June 17, 2019.

- ^ Jon Hemmerdinger, Boston (December 12, 2019). "FAA 2018 analysis warned of 15 fatal Max crashes months before second accident". Flightglobal.

- ^ "Europe and Canada Just Signaled They Don't Trust the FAA's Investigation of the Boeing 737 MAX". Time. Archived from the original on March 29, 2019. Retrieved March 20, 2019.

- ^ "How much was pilot error a factor in the Boeing 737 MAX crashes?". The Seattle Times. May 15, 2019. Retrieved July 15, 2020.

- ^ "Blaming Dead Pilots Brought to You by Boeing". Corporate Crime Reporter. May 22, 2019. Retrieved July 15, 2020.

- ^ Gregory Polek (November 27, 2019). "FAA To Take Full Control of Max Airworthiness Certification". AIN online.

- ^ "Boeing Statement on 737 MAX Simulator Training" (Press release). Boeing. January 7, 2020.

- ^ Jon Hemmerdinger (May 27, 2020). "Boeing restarts 737 Max production". Flightglobal.

- ^ Wolfsteller, Pilar (July 1, 2020). "FAA completes three days of 737 Max flight testing". Flight Global.

- ^ "After 18-Month Investigation, Chairs DeFazio and Larsen Release Final Committee Report on Boeing 737 MAX" (Press release). House Committee on Transportation and Infrastructure. September 16, 2020.

- ^ Hemmerdinger, Jon (September 30, 2020). "FAA's Dickson flies Max, declares 'I like what I saw'". Flight Global.

- ^ "Report: Europe closing in on decision to let 737 Max fly". AP News. October 16, 2020.

- ^ Chokshi, Niraj (November 18, 2020). "Boeing's 737 Max Will Be Flying Again. What Do Travelers Need to Know?". The New York Times. Retrieved November 18, 2020.

- ^ "Boeing 737 Max: Brazilian airline resumes passenger flights". BBC News. December 9, 2020.

- ^ Zeleny, Jeff; Schouten, Fredreka (March 12, 2019). "Trump speaks to Boeing CEO following tweets on airline technology". CNN. Retrieved December 19, 2019.

- ^ Shih, Gerry (March 12, 2019). "China's ban on the Boeing 737 Max inspires others, ramps up pressure on U.S. regulator". The Washington Post.

- ^ Frost, Natasha (March 13, 2019). "The US is increasingly alone in not grounding the Boeing 737 Max". Quartz. Retrieved February 24, 2020.

- ^ "U.S. Senate to hold crash hearing as lawmakers urge grounding Boeing 737 MAX 8". Reuters. March 12, 2019.

- ^ Kaplan, Thomas; Austen, Ian; Gebrekidan, Selam (March 13, 2019). "U.S. Grounds Boeing Planes, After Days of Pressure". The New York Times. Retrieved March 14, 2019.

- ^ "Boeing 737 Max 8 planes grounded after Ethiopian crash". CNN. March 13, 2019. Retrieved March 15, 2019.

- ^ Lu, Denise; Mccann, Allison; Wu, Jin; Lai, K.K. Rebecca (March 13, 2019). "From 8,600 Flights to Zero: Grounding the Boeing 737 Max 8". The New York Times. Retrieved December 24, 2019.

- ^ Langewiesche, William (September 18, 2019). "What Really Brought Down the Boeing 737 Max?". The New York Times Magazine.

- ^ "Boeing Statement on Lion Air Flight 610 Preliminary Report" (Press release). Boeing. November 27, 2018.

- ^ Picheta, Rob (March 10, 2019). "Ethiopian Airlines crash is the second disaster involving Boeing 737 MAX 8 in months". CNN. Retrieved March 10, 2019.

- ^ "Indonesia to Fault 737 MAX Design, U.S. Oversight in Lion Air Crash Report". msn.com. Retrieved October 28, 2019.

- ^ Pasztor, Andy; Tangel, Andrew (September 22, 2019). "Indonesia to Fault 737 MAX Design, U.S. Oversight in Lion Air Crash Report". The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved September 23, 2019.

- ^ Liebermann, Oren. "Investigators spread blame in Lion Air crash, but mostly fault Boeing and FAA". CNN. Retrieved October 26, 2019.

- ^ Pasztor, Andy; Otto, Ben; Tangel, Andrew (October 25, 2019). "Boeing, FAA and Lion Air Failures Laid Bare in 737 MAX Crash Report". The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved October 25, 2019.

- ^ "Boeing expects 737 Max to fly again by New Year". BBC News Online. October 23, 2019. Retrieved October 23, 2019.

- ^ "Boeing fires commercial planes boss as 737 MAX crisis deepens: SKY". sky. October 23, 2019. Retrieved October 23, 2019.

- ^ Aircraft Accident Investigation Report - Update. Final Report (Aviation Division): PT. Lion Mentari Airlines; Boeing 737-8 (MAX); PK-LQP, Tanjung Karawang, West Java, 29 October 2018 (PDF). October 25, 2019.

- ^ "U.S. Joins Other Nations in Grounding Boeing Plane". The New York Times. March 13, 2019. Retrieved March 15, 2019.

- ^ "Piece Found at Boeing 737 Crash Site Shows Jet Was Set to Dive". Bloomberg News. March 14, 2019. Retrieved March 16, 2019.

- ^ Nicas, Jack; Kaplan, Thomas; Glanz, James (March 15, 2019). "New Evidence in Ethiopian 737 Crash Points to Connection to Earlier Disaster". The New York Times. Retrieved March 15, 2019.

- ^ Glanz, James; Lai, K.K. Rebecca; Wu, Jin (March 13, 2019). "Why Investigators Fear the Two Boeing 737s Crashed for Similar Reasons". The New York Times. Retrieved March 15, 2019.

- ^ Lazo, Luz; Schemm, Paul, Aratani, Lori. "Investigators find 2nd piece of key evidence in crash of Boeing 737 Max 8 in Ethiopia". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on 17 March 2019. Retrieved 16 March 2019.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Schemm, Paul (March 13, 2019). "Ethiopian pilots received new training for 737 Max after Indonesian crash". The Washington Post.

- ^ Gates, Dominic (April 3, 2019). "Why Boeing's emergency directions may have failed to save 737 MAX". The Seattle Times. Retrieved September 27, 2019.

- ^ Siddiqui, Faiz (10 March 2019). "U. S. authorities to assist in investigation of Ethiopian Airlines crash that killed 157". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on 11 March 2019. Retrieved 10 March 2019.

- ^ McKirdy, Euan; Berlinger, Joshua; Levenson, Eric. "Ethiopian Airlines plane crash". CNN. Archived from the original on 11 March 2019. Retrieved 11 March 2019.

- ^ Hepher, Tim (13 March 2019). "France to analyze Ethiopian Airlines flight recorders: spokesman". Reuters. Archived from the original on 14 March 2019. Retrieved 14 March 2019.

- ^ Kiernan, Kristy. "The Black Boxes From Ethiopian Flight 302: What's On Them And What Investigators Will Look For". Forbes. Archived from the original on 15 March 2019. Retrieved 16 March 2019.

- ^ "Data on Ethiopia crash: 'Clear similarity' to Indonesia crash". Politico. Archived from the original on 27 March 2019. Retrieved 25 March 2019.

- ^ Schemm, Paul (March 17, 2019). "'Black box' data show 'clear similarities' between Boeing jet crashes, official says". Los Angeles Times. The Washington Post. Retrieved March 22, 2019.

- ^ Schemm, Paul (March 17, 2019). "Ethiopian official: Black box data shows 'clear similarities' between Ethiopian Airlines, Lion Air crashes". The Washington Post. Retrieved July 28, 2019.

- ^ Mohammad Azka, Rinaldi. "Alasan KNKT Minta Dilibatkan Menginvestigasi Tragedi Ethiopian Airlines" [Reasons NTSC Asked To Be Involved In Investigating Ethiopian Airlines Tragedy] (in Indonesian). Bisnis. Archived from the original on 15 March 2019. Retrieved 14 March 2019.

- ^ Christy Rosana, Fransisca. "KNKT Tawarkan Bantuan Investigasi Kecelakaan Ethiopian Airlines" [NTSC Offers Ethiopian Airlines Accident Investigation Assistance] (in Indonesian). Tempo. Archived from the original on 15 March 2019. Retrieved 14 March 2019.

- ^ "Aircraft Accident Investigation Bureau Interim Report" (PDF). Ethiopian Civil Aviation Authority, Ministry of Transport (Ethiopia). March 9, 2020. Retrieved March 25, 2020.

- ^ Levin, Alan (March 7, 2020). "Boeing Set to Get Blame in Ethiopian Report on Crash of 737 Max". Bloomberg. Retrieved March 7, 2020.

- ^ Marks, Simon; Dahir, Abdi Latif (March 9, 2020). "Ethiopian Report on 737 Max Crash Blames Boeing". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved March 11, 2020.

- ^ "Boeing nearing 737 Max fleet bulletin on AoA warning after Lion Air crash". The Air Current. November 7, 2018. Retrieved July 10, 2019.

- ^ "FAA issues emergency AD regarding potential erroneous AOA input on Boeing 737 MAX". ASN News. November 7, 2018. Retrieved June 7, 2019.

- ^ Tangel, Andrew; Pasztor, Andy (July 31, 2019). "Regulators Found High Risk of Emergency After First Boeing MAX Crash". The Wall Street Journal..

- ^ Kitroeff, Natalie (September 26, 2019). "Boeing Underestimated Cockpit Chaos on 737 Max, N.T.S.B. Says". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved September 26, 2019.

- ^ a b "Safety Recommendation Report: Assumptions Used in the Safety Assessment Process and the Effects of Multiple Alerts and Indications on Pilot Performance" (PDF). NTSB. September 19, 2019. Retrieved September 26, 2019.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|lay-url=ignored (help) This article incorporates public domain material from websites or documents of the National Transportation Safety Board.

This article incorporates public domain material from websites or documents of the National Transportation Safety Board.

- ^ "NTSB Issues 7 Safety Recommendations to FAA related to Ongoing Lion Air, Ethiopian Airlines Crash Investigations". NTSB. Retrieved September 30, 2019.

- ^ Hill, Andrew (October 6, 2019). "Boeing report highlights human factors no company should ignore". Financial Times.

- ^ Pasztor, Andy (September 26, 2019). "Plane Tests Must Use Average Pilots, NTSB Says After 737 MAX Crashes". The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved September 27, 2019.

- ^ "Boeing Failed to Predict That Slew of 737 Max Warning Alarms Would Confuse Pilots, Investigators Say". Time. Retrieved September 27, 2019.

- ^ ICAO fact sheet: Accident investigation (PDF). ICAO. 2016.

- ^ "Boeing's 737 MAX Crisis: Coverage by The Seattle Times". The Seattle Times. December 15, 2019. Retrieved March 5, 2020.

- ^ Gates, Dominic; Miletich, Steve; Kamb, Lewis (October 2, 2019). "Boeing pushed FAA to relax 737 MAX certification requirements for crew alerts". The Seattle Times. Retrieved October 4, 2019.

- ^ Slotnick, David. "The DOJ is reportedly probing whether Boeing's chief pilot misled regulators over the 737 Max". Business Insider. Retrieved February 22, 2020.

- ^ Isidore, Chris (January 8, 2021). "Boeing agrees to pay $2.5 billion to settle charges it defrauded FAA on 737 Max". CNN Business.

- ^ "Inspector General report details how Boeing played down MCAS in original 737 MAX certification – and FAA missed it". The Seattle Times. June 30, 2020. Retrieved July 2, 2020.

- ^ "FAA Probing Boeing's Alleged Pressure on Designated Inspectors". BNN Bloomberg. July 9, 2020. Retrieved July 30, 2020.

- ^ "Transport Canada introduces additional requirements to allow for the return to service of the Boeing 737 MAX" (Press release). Transport Canada. January 18, 2021.

- ^ "Boeing 737 Max cleared to fly in Europe after crashes". BBC News. January 27, 2021.

- ^ "Multi Operator Message" (PDF). MOM MOM 18 0664 01B. The Boeing Company. November 10, 2018. Retrieved August 1, 2021.

- ^ "Exclusive: Boeing kept FAA in the dark on key 737 MAX design changes - U.S. IG report". Reuters. July 1, 2020.

- ^ "Continued Airworthiness Notification to the International Community" (PDF). FAA. March 11, 2019. Archived from the original (PDF) on May 13, 2023.

- ^ "Boeing's MCAS may not have been needed on the 737 Max at all". The Air Current. January 10, 2021. Retrieved August 3, 2021.

- ^ "Airworthiness Directives; The Boeing Company Airplanes". rgl.faa.gov. November 20, 2020. Archived from the original on April 18, 2022. Retrieved December 12, 2020.

- ^ Lahiri, Tripti (March 11, 2019). "China is the first country to ground the Boeing 737 Max after its two crashes". Quartz. Retrieved August 8, 2020.

- ^ Josephs, Leslie (October 29, 2019). "In brutal Senate hearing, Boeing admits its safety assessments of 737 Max fell short". CNBC.

- ^ "How Boeing went from appealing for government aid to snubbing it". Reuters. May 2, 2020. Retrieved July 22, 2020.

- ^ "FAA clears Boeing 737 Max to fly again 20 months after grounding over deadly crashes". November 18, 2020. Archived from the original on November 18, 2020. Retrieved November 18, 2020.

- ^ Chris Isidore (November 17, 2020). "Boeing's 737 Max debacle could be the most expensive corporate blunder ever". CNN. Retrieved November 21, 2020.

- ^ "Boeing refuses to play ball as Dutch MPs reopen 2009 crash involving 737". smmry.com. Retrieved February 8, 2020.

Further reading

- The real reason Boeing's new plane crashed twice. Vox Videos. April 15, 2019.

- Travis, Gregory (April 18, 2019). "How the Boeing 737 Max Disaster Looks to a Software Developer". IEEE Spectrum.

- "Timeline: The Boeing 737 MAX Crisis". Aviation Week Network. May 16, 2019.

- Leggett, Theo (May 17, 2019). "What went wrong inside Boeing's cockpit?". BBC News Online.

- Cox, John (May 20, 2019). "This [the emergency the pilots faced] is not simple". Leeham News.

- Gelles, David; Wichter, Zach (July 18, 2019). "Boeing 737 Max: The Latest on the Deadly Crashes and the Fallout". The New York Times.

- Broderick, Sean (August 15, 2019). "The MAX Saga, One Question At A Time". Aviation Week & Space Technology.

- Hemmerdinger, Jon (September 13, 2019). "Six months on from the Boeing 737 Max grounding". FlightGlobal.

- "Boeing 737 MAX Flight Control System - Observations, Findings, and Recommendations" (PDF). Joint Authorities Technical Review. October 11, 2019.

- "System Failure: The Boeing Crashes". Al Jazeera Media Network. October 16, 2019.

- "After Lion Air crash, Boeing doubled down on faulty 737 MAX assumptions". The Seattle Times. November 8, 2019. Retrieved October 2, 2020.

- David Kaminski-Morrow (March 13, 2020). "Why restarting Max production is just the start of Boeing's delivery challenges". FlightGlobal.

- Jon Hemmerdinger (March 13, 2020). "How the 737 Max grounding changed commercial aerospace". FlightGlobal.

- Dan Thisdell (March 13, 2020). "Tarnished Max brand presents major challenge for Boeing". FlightGlobal.

- Baker, Sinéad. "Boeing shunned automation for decades. When the aviation giant finally embraced it, an automated system in the 737 Max kicked off the biggest crisis in its history". Business Insider. Retrieved April 7, 2020.

- Delbert, Caroline (April 14, 2020). "The 737 MAX Has Been Grounded for a Year Because of Its Terrible Computers". Popular Mechanics. Retrieved April 15, 2020.

- Wolfsteller2020-07-01T19:07:00+01:00, Pilar. "Inspector general slams Boeing for holding back information on 737 Max". Flight Global. Retrieved July 2, 2020.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link)