Easter Rising: Difference between revisions

Undid revision 279940863 by Purple Arrow (talk)Restoring referenced text |

|||

| Line 22: | Line 22: | ||

{{Campaignbox Irish independence}} |

{{Campaignbox Irish independence}} |

||

The '''Easter Rising''' ({{lang-ga|Éirí Amach na Cásca}})<ref>[http://www.taoiseach.gov.ie/irish/index.asp?docID=2532 Department of the Taoiseach - Easter Rising]</ref> was an insurrection staged in [[Ireland]] during [[Easter Week]], 1916. The Rising was an attempt by [[Irish republicanism|Irish republicans]] to |

The '''Easter Rising''' ({{lang-ga|Éirí Amach na Cásca}})<ref>[http://www.taoiseach.gov.ie/irish/index.asp?docID=2532 Department of the Taoiseach - Easter Rising]</ref>, also known as the '''Easter Rebellion'''<ref>Max Caulfield (1995), ''The Easter Rebellion: Dublin 1916''. Roberts Rinehart Publishers. ISBN-13: 978-1570980428 </ref><ref>[http://209.85.129.132/search?q=cache:QJhoU0eiOG4J:www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/176916/Easter-Rising+encylopedia+britannica+easter+rebellion&cd=1&hl=en&ct=clnk&gl=uk Encyclopaedia Britannica]</ref><ref>BBC. ''1910-16: The 'winning' of Home Rule to the Easter Rebellion: [http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/events/northern_ireland/history/299118.stm]</ref><ref>[http://www.history.com/encyclopedia.do?articleId=208140 History.com Encyclopaedia]</ref> was an insurrection staged in [[Ireland]] during [[Easter Week]], 1916. The Rising was an attempt by [[Irish republicanism|Irish republicans]] to gain independence from [[United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland|Britain]].<ref>[http://www.bbc.co.uk/history/british/easterrising/insurrection/in05.shtml BBC: ''Blood sacrifice'']</ref> It was the most significant uprising in Ireland since the [[Irish Rebellion of 1798|rebellion of 1798]]. |

||

Organised by the Military Council of the [[Irish Republican Brotherhood]],<ref>[http://books.google.com/books?id=_RhCAAAAIAAJ&dq=%22military+council%22+irb&q=%22military+council%22+&pgis=1#search_anchor''Leaders and Men of the Easter Rising: Dublin 1916''] |

Organised by the Military Council of the [[Irish Republican Brotherhood]],<ref>[http://books.google.com/books?id=_RhCAAAAIAAJ&dq=%22military+council%22+irb&q=%22military+council%22+&pgis=1#search_anchor''Leaders and Men of the Easter Rising: Dublin 1916''] |

||

Revision as of 10:21, 27 March 2009

| Easter Rising | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the movement towards Irish independence | |||||||

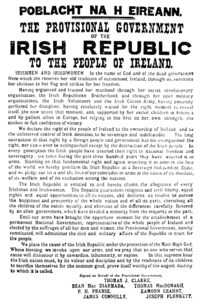

Proclamation of the Republic, Easter 1916 | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

Irish Volunteers Irish Citizen Army Cumann na mBan Hibernian Rifles Fianna Éireann |

Dublin Metropolitan Police Royal Irish Constabulary | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

1,250 in Dublin, ~2,000–3,000 elsewhere, although they took little or no action. | 16,000 troops and 1,000 armed police in Dublin by end of the week. | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 82 killed, 1,617 wounded, 16 executed | 157 killed, 318 wounded | ||||||

| 220 civilians killed, 600 wounded | |||||||

The Easter Rising (Irish: Éirí Amach na Cásca)[1], also known as the Easter Rebellion[2][3][4][5] was an insurrection staged in Ireland during Easter Week, 1916. The Rising was an attempt by Irish republicans to gain independence from Britain.[6] It was the most significant uprising in Ireland since the rebellion of 1798.

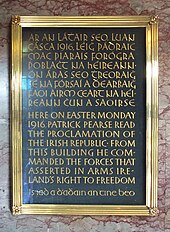

Organised by the Military Council of the Irish Republican Brotherhood,[7] the Rising lasted from Easter Monday 24 April to 30 April 1916. Members of the Irish Volunteers, led by schoolteacher and barrister Patrick Pearse, joined by the smaller Irish Citizen Army of James Connolly, along with 200 members of Cumann na mBan, seized key locations in Dublin and proclaimed an Irish Republic independent of Britain. There were some actions in other parts of Ireland but, except for the attack on the RIC barracks at Ashbourne, County Meath, they were minor.

The Rising was suppressed after seven days of fighting, and its leaders were court-martialled and executed, but it succeeded in bringing physical force republicanism back to the forefront of Irish politics. In the 1918 General Election, the last all-island election held in Ireland, to the British Parliament, Republicans won 73 seats out of 105, on a policy of abstentionism from Westminster and Irish independence. This came less than two years after the Rising. In January 1919, the elected members of Sinn Féin who were not still in prison at the time, including survivors of the Rising, convened the First Dáil and established the Irish Republic. The British Government refused to accept the legitimacy of the newly declared nation, leading to the Irish War of Independence.

Background

Since the Act of Union 1800 that joined Ireland and Great Britain to form the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, opposition to the union had taken two forms: parliamentary constitutionalism and physical force.

Daniel O’Connell, who founded the Repeal Association in 1840, pursued repeal of the Act in the British House of Commons and through mass meetings. The Young Irelanders were active members of the repeal movement, but broke with O’Connell in 1846 and established the Irish Confederation, and its leaders, William Smith O'Brien, Thomas Francis Meagher and John Blake Dillon, led the Young Irelander Rebellion of 1848. The Fenians staged another revolt in 1867. Though defeated, they continued as a secret, oath-bound society.[8] In 1873, a Fenian convention was held in Dublin, and adopted the name Irish Republican Brotherhood, and a constitution. It passed two resolutions: that the central committee of the IRB constituted itself to act as the government of the Irish Republic, and that the Head Centre (chairman) of the IRB would be President of the Republic, until such time as the Irish people freely elected its own government. [9]

The Home Rule League and Charles Stewart Parnell’s Irish Parliamentary Party succeeded in having a large number of members elected to Westminster where, through the tactic of obstructionism and by virtue of holding the balance of power, they succeeded in having three Home Rule bills introduced. Parnell's objectives, however, went beyond that of limited Home Rule. This became clear when in a speech in January 1885, he said "No man has a right to fix the boundary of a march of a nation..." [10] The First Home Rule Bill of 1886 was defeated in the House of Commons. The Second Home Rule Bill of 1893 was passed by the Commons but rejected by the House of Lords. The Third Home Rule Bill of 1912 was again rejected by the Lords, but under the Parliament Act 1911 (passed by H. H. Asquith with the support of John Redmond who became IPP leader on the death of Parnell) would become law after two years. Redmond, unlike Parnell, saw Home Rule as an end in itself. [11]

Ulster Unionists, led by Sir Edward Carson, and both the Tories and Lords were opposed to home rule, seeing it as a threat to their interests. The Unionists formed the Ulster Volunteer Force on 13 January 1913, prepared to violently resist the imposition of home rule, and threats of force were made by Conservative leader Andrew Bonar Law and other members of his party.[12][13][14] This led to the formation of the Irish Volunteers, a force dedicated to defending home rule, on 25 November 1913.[15] The Home Rule Act received Royal Assent on 18 September 1914, but excluded an as yet undefined area in the Province of Ulster.[16] The Bill was then suspended until after the World War, which had broken out a month previously, causing the Irish Volunteers to split, a majority called the National Volunteers supporting the Allied and British war effort. Meanwhile, the IRB, reorganised by determined men such as Thomas Clarke,[17] and Seán MacDermott, continued to plan, not for limited home rule under the British Crown, but for an independent Irish Republic. [18]

Planning the Rising

Plans for the Easter Rising began within days of the August declaration of the war against Germany. The Supreme Council of the IRB held a meeting in 25 Parnell Square and, under the old dictum that "England's difficulty is Ireland's opportunity", decided to take action sometime before the conclusion of the war. The Council made three decisions: to establish a military council, seek whatever help possible from Germany, and secure control of the Volunteers.

Although the overall ambition of the IRB was the establishment of an independent Irish Republic, it was not necessarily through a single act of rebellion that this was to be achieved. Historian Eoin Neeson suggests that a plan involving a military victory was never a consideration, allowing that the leaders considered there would be some military success.[19] The IRB set out three objectives for the Rising: First, declare an Irish Republic, second, revitalise the spirit of the people and arouse separatist national fervour, and thirdly, claim a place at the post war peace conference. [20]

To this end, the IRB's treasurer, Tom Clarke, formed a Military Council to plan the rising, initially consisting of Patrick Pearse, Eamonn Ceannt, and Joseph Plunkett, with himself and Seán Mac Diarmada added shortly thereafter. All of these were members of the IRB, and all but Clarke were members of the Irish Volunteers.[20]

The second objective of the IRB was at this stage already well advanced. The IRB had infiltrated a number of social organisations, including the Gaelic Athletic Association[21], the Gaelic League, Sinn Féin, trade unions, and later the Irish Citizen Army. Through these organisations they wanted to provide the drive for nationalism, separatism and ultimately change.[20]

Since its inception in 1913, the Volunteers, whose formation was instigated by the IRB precisely for the purpose of staging a rising,[22] was increasingly coming under the control of that organisation, as IRB members worked to promote one another to officer rank whenever possible; hence by 1916 a large proportion of the Volunteer leadership were devoted republicans. A notable exception was their founder and Chief-of-Staff Eoin MacNeill who at the time was unaware of the IRB's intentions. MacNeill planned to use the Volunteers as a bargaining tool with Britain following World War I.[23] [24]

Negotiations were opened with the German High Command, represented by Count Bethmann-Hollweg, Count Rudolph Nadolny and Captain Heydal in Germany. The IRB was represented by Joseph Plunkett (who travelled to Berlin in 1915) in addition to his father, Count Plunkett. [25] Roger Casement, who had been in Germany since 1914, negotiated separately as the representative of the Volunteers. Casement was never a member of the IRB, and was kept unaware of the degree that the IRB had infiltrated the Volunteers.[26] Casement's aims were to form an brigade of Irish POWs in German camps who would be released in order to fight against England on this side of Ireland, as well as to secure a shipment of weapons from Germany for the under-equipped Volunteers. The former proved unsuccessful, and while he did manage to secure a shipment of rifles, the German aid was less than he had hoped.

In America also there were negotiations taking place with the German Ambassador in Washington, D.C., Count Johann Heinrich von Bernsdorff, and first secetary, Wolf von Igel. John Devoy, leader of Clan na Gael, was also involved in these negotiations, which were to continue through 1914, 1915 and 1916. From these negotiations the IRB received the agreement from the German government that if the Irish could establish their status as a nation “deprived of lawful statehood,” then Germany would afford them a hearing at the post-war peace conference.[27]

James Connolly, head of the Irish Citizen Army (ICA), a group of armed socialist trade union men and women, were completely unaware of the IRB's plans, and threatened to initiate a rebellion on their own if other parties refused to act. As the ICA was barely 200 strong, any action they might take would have been in the nature of a forlorn hope. Though if they had decided to go it alone, the IRB and the Volunteers would possibly have come to their aid. [28] Thus the IRB leaders met with Connolly in January 1916 and convinced him to join forces with them. They agreed to act together the following Easter and made Connolly the sixth member of the Military Committee (Thomas MacDonagh would later become the seventh and final member).

In an effort to thwart informers and, indeed, the Volunteers' own leadership, Pearse issued orders in early April for three days of "parades and manoeuvres" by the Volunteers for Easter Sunday (which he had the authority to do, as Director of Organization). The idea was that the republicans within the organization (particularly IRB members) would know exactly what this meant, while men such as MacNeill and the British authorities in Dublin Castle would take it at face value. However, MacNeill got wind of what was afoot and threatened to "do everything possible short of phoning Dublin Castle" to prevent the rising.

MacNeill was briefly convinced to go along with some sort of action when Mac Diarmada revealed to him that a shipment of German arms was about to land in County Kerry, planned by the IRB in conjunction with Roger Casement; he was certain that the authorities discovery of such a shipment would inevitably lead to suppression of the Volunteers, thus the Volunteers were justified in taking defensive action (including the originally planned maneuvers). [29] Casement, disappointed with the level of support offered by the Germans, returned to Ireland on a German U-boat and was captured upon landing at Banna Strand in Tralee Bay. The arms shipment, aboard the German ship Aud — disguised as a Norwegian fishing trawler—had been scuttled after interception by the British navy, as the local Volunteers had failed to rendezvous with it.

The following day, MacNeill reverted to his original position when he found out that the ship carrying the arms had been scuttled. With the support of other leaders of like mind, notably Bulmer Hobson and The O'Rahilly, he issued a countermand to all Volunteers, canceling all actions for Sunday. This only succeeded in putting the rising off for a day, although it greatly reduced the number of Volunteers who turned out.

British Naval Intelligence had been aware of the arms shipment, Casement's return and the Easter date for the rising through radio messages between Germany and its embassy in the United States that were intercepted by the Navy and deciphered in Room 40 of the Admiralty.[30] The information was passed to the Under-Secretary for Ireland, Sir Matthew Nathan, on 17 April, but without revealing its source, and Nathan was doubtful about its accuracy.[31] When news reached Dublin of the capture of the Aud and the arrest of Casement, Nathan conferred with the Lord Lieutenant, Lord Wimborne. Nathan proposed to raid Liberty Hall, headquarters of the Citizen Army, and Volunteer properties at Father Matthew Park and at Kimmage, but Wimborne was insisting on wholesale arrests of the leaders. It was decided to postpone action until after Easter Monday and in the meantime Nathan telegraphed the Chief Secretary, Augustine Birrell, in London seeking his approval.[32] By the time Birrell cabled his reply authorising the action, at noon on Monday 24 April 1916, the Rising had already begun.

The Rising

Easter Monday

The Volunteers' Dublin division was organized into four battalions. As a result of the countermanding order all of them saw a far smaller turnout than originally planned. The 1st battalion under Commandant Ned Daly mustered at Blackhall Street, numbering about 250 men. They were to occupy the Four Courts and areas to the northwest to guard against attack from the west, principally from the Royal and Marlborough Barracks; the exception was D Company, 1st Battalion, a company of 12 men led by Captain Seán Heuston, who were to occupy the Mendicity Institution, across the river from the Four Courts. The 2nd battalion comprised about 200 men under Commandant Thomas MacDonagh who gathered at St. Stephen's Green with orders to take Jacob's Biscuit Factory, Bishop Street, south of the city centre, and a smaller number of men who gathered at Fairview, in the northeast, and who were later directed to the General Post Office.[33] In the southeast Commandant Éamon de Valera commanded about 130 men of the 3rd battalion who would take Boland's Bakery and a number of surrounding buildings to cover Beggars Bush Barracks and the main road and railway from Kingstown (now Dún Laoghaire) harbour. Commandant Éamonn Ceannt's 4th battalion, numbering about 100 men, mustered at Emerald Square in Dolphin's Barn; They were to occupy the workhouse known as the South Dublin Union to the southwest and defend against attack from the Curragh.[34] A joint force of about 400 Volunteers and Citizen Army gathered at Liberty Hall under the command of Commandant James Connolly. Of these, about 100 men and women of the Citizen Army under Commandant Michael Mallin were sent to occupy St. Stephen's Green, and a small detachment of the Citizen Army under Captain Seán Connolly were directed to seize the area around the City Hall, next to Dublin Castle, including the offices of the Daily Express.[35] The remainder was to occupy the General Post Office. This was the headquarters battalion, and as well as Connolly it included four other members of the Military Council: Patrick Pearse, President and Commander-in-Chief, Tom Clarke, Seán Mac Dermott and Joseph Plunkett.[36]

At midday a small team of Volunteers and Fianna members attacked the Magazine Fort in the Phoenix Park and disarmed the guards, with the intent to seize weapons and blow up the building as a signal that the rising had begun. They set explosives but failed to obtain any arms. The explosion was not loud enough to be heard in the city.[37] At the same time the Volunteer and Citizen Army forces throughout the city moved to occupy and secure their positions. Seán Connolly's unit made an assault on Dublin Castle, shooting dead a police sentry and overpowering the soldiers in the guardroom, but did not press home the attack. The Under-secretary, Sir Matthew Nathan, who was in his office with Colonel Ivor Price, the Military Intelligence Officer, and A. H. Norway, head of the Post Office, was alerted by the shots and helped close the castle gates.[38] The rebels occupied the Dublin City Hall and adjacent buildings. Mallin's detachment, which was joined by Constance Markiewicz (Countess Markiewicz), occupied St. Stephen's Green, digging trenches and commandeering vehicles to build barricades. They took several buildings, including the Royal College of Surgeons, but did not make an attempt on the Shelbourne Hotel, a tall building overlooking the park.[39] Daly's men, erecting barricades at the Four Courts, were the first to see action. A troop of the 5th and 12th Lancers, part of the 6th Cavalry Reserve Regiment, was escorting an ammunition convoy along the north Quays when it came under fire from the rebels. Unable to break through, they took refuge in nearby buildings.[40] The headquarters battalion, led by Connolly, marched the short distance to O'Connell Street. They charged the GPO, expelled customers and staff, and took a number of British soldiers prisoner. Two flags were hoisted on the flag poles on either end of the GPO roof: the tricolour at the right corner at Henry Street and a green flag with the inscription 'Irish Republic' at the left corner at Princess Street. A short time later, Pearse read the Proclamation of the Republic outside the GPO.[41]

The Commander-in-Chief of the British Army in Ireland, General Lovick Friend, was on leave in England. When the insurrection began the Officer Commanding the Dublin Garrison, Colonel Kennard, could not be located. His adjutant, Col. H. V. Cowan, telephoned Marlborough Barracks and asked for a detachment of troops to be sent to Sackville Street (O'Connell Street) to investigate the situation at the GPO. He then telephoned Portobello, Richmond and the Royal Barracks and ordered them to send troops to relieve Dublin Castle. Finally, he contacted the Curragh and asked for reinforcements to be sent to Dublin. [42] A troop of the 6th Reserve Cavalry Regiment, dispatched from Marlborough Barracks, proceeded down O'Connell Street. As it passed Nelson's Pillar, level with the GPO, the rebels opened fire, killing three cavalrymen and two horses[43] and fatally wounding a fourth man. The cavalrymen retreated and were withdrawn to barracks. This action is often referred to, inaccurately, as the "Charge of the Lancers." [44]

A piquet from the 3rd (Reserve) Battalion, Royal Irish Regiment (RIR), approaching the city from Richmond Barracks, encountered an outpost of Éamonn Ceannt's force under Section-Commander John Joyce in Mount Brown, at the north-western corner of the South Dublin Union. A party of twenty men under Lieutenant George Malone was ordered to march on to Dublin Castle. They proceeded a short distance with rifles sloped and unloaded before coming under fire, losing three men in the first volley, then broke into a tan-yard opposite. Malone's jaw was shattered by a bullet as he went in. The Commanding Officer, Lieutenant-Colonel R. L. Owens, brought up the remainder of his men from Richmond Barracks. A company with a Lewis Gun was sent to the Royal Hospital (not then a hospital but the British military headquarters), overlooking the Union. The main body took up positions along the east and south walls of the Union, occupying houses and a block of flats, then opened fire on the rebel positions, forcing Joyce and his men to retreat across open ground. A party led by Lieut. Alan Ramsey broke open a small door next to the Rialto gate, but Ramsey was shot and killed, and the attack was repulsed. A second wave led by Capt. Warmington charged the door but Warmington, too, was killed. The remaining troops, trying to break in further along the wall, were enfiladed from Jameson's distillery in Marrowbone Lane. Eventually the superior numbers and firepower of the British were decisive; they forced their way inside and the small rebel force in the tin huts at the eastern end of the Union surrendered.[45]

Tuesday to Saturday

This article includes a list of references, related reading, or external links, but its sources remain unclear because it lacks inline citations. (January 2009) |

British forces initially put their efforts into securing the approaches to Dublin Castle and isolating the rebel headquarters, which they believed was in Liberty Hall. The British commander, Brigadier-General Lowe, worked slowly, unsure of the size of the force he was up against, and with only 1,269 troops in the city when he arrived from the Curragh Camp in the early hours of Tuesday 25 April. City Hall was taken on Tuesday morning. The rebel position at St Stephen's Green, held by the Citizen Army under Michael Mallin, was made untenable after the British placed snipers and machine guns in the Shelbourne Hotel and surrounding buildings. As a result, Mallin's men retreated to the Royal College of Surgeons building. British firepower was provided by field artillery summoned from their garrison at Athlone which they positioned on the northside of the city at Phibsborough and at Trinity College, and by the patrol vessel Helga, which sailed upriver from Kingstown. Lord Wimborne, the Lord Lieutenant, declared martial law on Tuesday evening. On Wednesday, 26 April, the guns at Trinity College and Helga shelled Liberty Hall, and the Trinity College guns then began firing at rebel positions in O'Connell Street.

Reinforcements were sent to Dublin from England, and disembarked at Kingstown on the morning of 26 April. Heavy fighting occurred at the rebel-held positions around the Grand Canal as these troops advanced towards Dublin. The Sherwood Foresters were repeatedly caught in a cross-fire trying to cross the canal at Mount Street. Seventeen Volunteers were able to severely disrupt the British advance, killing or wounding 240 men.[citation needed] The rebel position at the South Dublin Union (site of the present day St. James's Hospital), further west along the canal, also inflicted heavy losses on British troops trying to advance towards Dublin Castle. Cathal Brugha, a rebel officer, distinguished himself in this action and was badly wounded.

The headquarters garrison, after days of shelling, were forced to abandon their headquarters when fire caused by the shells spread to the GPO. They tunnelled through the walls of the neighbouring buildings in order to evacuate the Post Office without coming under fire and took up a new position in 16 Moore Street. On Saturday 29 April, from this new headquarters, after realizing that they could not break out of this position without further loss of civilian life, Pearse issued an order for all companies to surrender. Pearce surrendered unconditionally to Brigadier-General Lowe. The surrender document read:

"In order to prevent the further slaughter of Dublin citizens, and in the hope of saving the lives of our followers now surrounded and hopelessly outnumbered, the members of the Provisional Government present at headquarters have agreed to an unconditional surrender, and the commandants of the various districts in the City and County will order their commands to lay down arms."

The Rising outside Dublin

This article includes a list of references, related reading, or external links, but its sources remain unclear because it lacks inline citations. (January 2009) |

Irish Volunteer units turned out for the Rising in several places outside of Dublin, but due to Eoin MacNeill's countermanding order, most of them returned home without fighting. In addition, due to the interception of the German arms aboard the Aud, the provincial Volunteer units were very poorly armed.

At Ashbourne, County Meath, the North County Dublin Volunteers (also known as the Fingal Volunteers), led by Thomas Ashe and his second in command Richard Mulcahy, attacked the RIC barracks. Reinforcements came from Slane and after a five-hour battle, the Volunteers captured over 90 prisoners. There were 8–10 RIC deaths and two Volunteer fatalities, John Crennigan and Thomas Rafferty. The action pre-figured the guerrilla tactics of the Irish Republican Army in the Irish War of Independence from 1919 to 1921. Elsewhere in the east, Seán MacEntee and County Louth Volunteers killed a policeman and a prison guard. In County Wexford, the Volunteers took over Enniscorthy from Tuesday until Friday, before symbolically surrendering to the British Army at Vinegar Hill – site of a famous battle during the Irish Rebellion of 1798.

In the west, Liam Mellows led 600-700 Volunteers in abortive attacks on several police stations, at Oranmore and Clarinbridge in County Galway. There was also a skirmish at Carnmore in which two RIC men were killed. However his men were poorly-armed, with only 25 rifles and 300 shotguns, many of them being equipped only with pikes. Towards the end of the week, Mellows' followers were increasingly poorly-fed and heard that large British reinforcements were being sent westwards. In addition, the British warship, HMS Gloucester arrived in Galway Bay and shelled the fields around Athenry where the rebels were based. On 29 April the Volunteers, judging the situation to be hopeless, dispersed from the town of Athenry. Many of these Volunteers were arrested in the period following the rising, while others, including Mellows had to go "on the run" to escape. By the time British reinforcements arrived in the west, the rising there had already disintegrated.

In the north, several Volunteer companies were mobilised in County Tyrone and 132 men on the Falls Road in Belfast.

In the south, around 1,000 Volunteers mustered in Cork, under Tomás Mac Curtain on Easter Sunday, but they dispersed after receiving several contradictory orders from the Volunteer leadership in Dublin.

Casualties

The British Army reported casualties of 116 dead, 368 wounded and 9 missing. 16 policemen died and 29 were wounded. Irish casualties were 318 dead and 2,217 wounded. The Volunteers and ICA recorded 64 killed in action, but otherwise Irish casualties were not divided into rebels and civilians.[47]

Aftermath

General Maxwell quickly signalled his intention “to arrest all dangerous Sinn Feiners,” including “those who have taken an active part in the movement although not in the present rebellion,”[48] reflecting the popular belief that Sinn Féin, a separatist organisation that was neither militant nor republican, was behind the Rising.

A total of 3,430 men and 79 women were arrested, although most were subsequently released. In attempting to arrest members of the Kent family in County Cork on 2 May, a Head Constable was shot dead in a gun battle. Richard Kent was also killed, and Thomas and William Kent were arrested.

In a series of courts martial beginning on 2 May, ninety people were sentenced to death. Fifteen of those (including all seven signatories of the Proclamation) had their sentences confirmed by Maxwell and were executed by firing squad between 3 May and 12 May (among them the seriously-wounded Connolly, shot while tied to a chair due to a shattered ankle). Not all of those executed were leaders: Willie Pearse described himself as "a personal attaché to my brother, Patrick Pearse"; John MacBride had not even been aware of the Rising until it began, but had fought against the British in the Boer War fifteen years before; Thomas Kent did not come out at all—he was executed for the killing of a police officer during the raid on his house the week after the Rising. The most prominent leader to escape execution was Eamon de Valera, Commandant of the 3rd Battalion.

A Royal Commission was set up to enquire into the causes of the Rising. It began hearings on 18 May under the chairmanship of Lord Hardinge of Penshurst. The Commission heard evidence from Sir Matthew Nathan, Augustine Birrell, Lord Wimborne, Sir Neville Chamberlain (Inspector-General of the Royal Irish Constabulary), General Lovick Friend, Major Ivor Price of Military Intelligence and others.[49] The report, published on 26 June, was critical of the Dublin administration, saying that "Ireland for several years had been administered on the principle that it was safer and more expedient to leave the law in abeyance if collision with any faction of the Irish people could thereby be avoided."[50] Birrell and Nathan had resigned immediately after the Rising. Wimborne had also reluctantly resigned, but was re-appointed, and Chamberlain resigned soon after.

1,480 men were interned in England and Wales under Regulation 14B of the Defence of the Realm Act 1914, many of whom, like Arthur Griffith, had little or nothing to do with the affair. Camps such as Frongoch internment camp became “Universities of Revolution” where future leaders like Michael Collins, Terence McSwiney and J. J. O’Connell began to plan the coming struggle for independence.[51] Roger Casement was tried in London for high treason and hanged at Pentonville Prison on 3 August.

According to Peter Berresford Ellis it has become firmly set in people’s minds that the Dublin people jeered the prisoners as they were led off to imprisonment, and that this description of how Dublin viewed the insurrection has almost become written in stone. He suggests that it was certainly a view that the imperial propaganda of the time wanted to impress on everyone,[52] and that newspapers were unlikely to publish anything to the contrary. [53]

Examples cited [54] by Berresford Ellis include, Dorothy Macardle, writing in her The Irish Republic, "The people had not risen. Some had cursed the insurgents."[55] Thomas M. Coffey in Agony at Easter: The 1916 Irish Uprising writes, "The defeated insurgents quickly learnt how most Dubliners still felt about their rebellion when a raucous crowd came pouring out of the side streets to accost them ... The flood of insults was so fierce and vitriolic it hit the marching prisoners with an almost physical impact."[56]

According to Berresford Ellis this perspective became less tenable when a long obscure eyewitness account of the period resurfaced in 1991. Canadian journalist and writer, Frederick Arthur McKenzie, [57] was one of the best-known and reputable war correspondents of his day according to Berresford Ellis. He was one of two Canadian journalists who arrived in Dublin with the English reinforcements sent to put down the insurrection. McKenzie had no sympathy for the Irish ‘rebels’ and German sympathizers, as he perceived them, and was no anti-imperialist. [58]

McKenzie published The Irish Rebellion: What happened and Why, with C. Arthur Pearson in London in 1916, he notes, "I have read many accounts of public feeling in Dublin in these days. They are all agreed that the open and strong sympathy of the mass of the population was with the British troops. That this was in the better parts of the city, I have no doubt, but certainly what I myself saw in the poorer districts did not confirm this. It rather indicated that there was a vast amount of sympathy with the rebels, particularly after the rebels were defeated." Berresford Ellis then cites a passage by McKenzie describing how he watched as people were waving and cheering as a regiment approached, and that he commented to his companion they were cheering the soldiers. Noticing then that they were escorting Irish prisoners, he realised that they were actually cheering the rebels. The rebels he says were walking in military formation and were loudly and triumphantly singing a rebel song. McKenzie reports speaking to a group of men and women at street corners, "shure, we cheer them" said a woman, "why wouldn’t we? Aren't they our own flesh and blood." Dressed in khaki McKenzie was mistaken for a British soldier as he went about Dublin back streets were people cursed him openly, and "cursed all like me strangers in their city." J.W Rowath, a British officer had a comparable experience to McKenzie and observed that "crowds of men and women greeted us with raised fists and curses."[59]

Brian Barton & Micheal Foy cite Frank Robbins of the Irish Citizen Army who records seeing a group of Dubliners gathered to cheer the prisoners while being marched into Richmond barracks.[60] They also report de Valera’s surrendered Boland’s mill, were crowds lined the pavement in Grand Canal Street and Hogan Place and pleaded with the insurgents to take shelter in their houses rather than surrender. Foy and Barton concluded "Public attitudes locally were not uniformly hostile in an area which the police had come to regard as increasingly militant in the months before the Rising. Some of the British soldiers who fought there noted a strong antipathy towards them." At the South Dublin Union, Major de Courcy Wheeler noted that there was no hostility from the people towards the insurgents: "It was perfectly plain that all their admiration was for the heroes who had surrendered." [61]

This account flatly contradicts most of the contemporary accounts, says Berresford Ellis. [62] This is a view shared by Michael Foy and Brian Barton [63] also highlighting expressions of sympathy from the people who watched the prisoners being marched away. Quoting the diary of John Clarke a shopkeeper who writes "Thus ends the last attempt for poor old Ireland. What noble fellows. The cream of the land. None of your corner-boy class." [64]

Foy and Barton felt the contradictions could be modified by other factors. They examined the routes which the British soldiers took the prisoners. Michael Mallin’s column of prisoners they say were marched two miles to Richmond barracks through a "strongly loyalist and Protestant artisan class district." It was from this district that the Royal Dublin Fusiliers and other Irish regiments of the British army drew their recruits. It was around Richmond barracks they say, lived people who were economically dependent on the military. Another aspect they raise was the degree of hostility from Dublin women whose sons were serving in the army in France. They note that some priests at Church Street rebuked the insurgent prisoners and wounded. However the generally accepted account of the population of Dublin being uniformly hostile to the surrendered insurgents is one of the myths repeated so often as to become 'history.' [65]

Berresford Ellis concludes that it has becomes clear that the insurrection of 1916 needs more considered research and analysis before we can be certain that it is "assessed in its rightful historical context." The assertion that it was an unpopular rising by a small band who were jeered and insulted on their defeat as they were led off into captivity is just one of "the myths that have been propagated." [66]

A meeting called by Count Plunkett on 19 April 1917 led to the formation of a broad political movement under the banner of Sinn Féin[67] which was formalised at the Sinn Féin Ard Fheis of 25 October 1917. The Conscription Crisis of 1918 further intensified public support for Sinn Féin before the general elections to the British Parliament on 14 December 1918, which resulted in a landslide victory for Sinn Féin, whose MPs gathered in Dublin on 21 January 1919 to form Dáil Éireann and adopt the Declaration of Independence.[68]

Legacy of the Rising

Some survivors of the Rising went on to become leaders of the independent Irish state and those who died were venerated by many as martyrs. Their graves in Arbour Hill military prison in Dublin became a national monument and the text of the Proclamation was taught in schools. An annual commemoration, in the form of a military parade, was held each year on Easter Sunday, culminating in a huge national celebration on the 50th anniversary in 1966.[69]

With the outbreak of the Troubles in Northern Ireland, government, academics and the media began to revise the country’s militant past, and particularly the Easter Rising. The coalition government of 1973—1977, in particular the Minister for Posts and Telegraphs, Conor Cruise O'Brien, began to promote the view that the violence of 1916 was essentially no different to the violence then taking place in the streets of Belfast and Derry. Cruise O'Brien and others asserted that the Rising was doomed to military defeat from the outset, and that it failed to account for the determination of Ulster Unionists to remain in the United Kingdom.[70] "Revisionist" historians[71] began to write of it in terms of a "blood sacrifice."[72] While the Rising and its leaders continued to be venerated by Irish republicans – including members and supporters of the IRA and Sinn Féin – with murals in republican areas of Belfast and other towns celebrating the actions of Pearse and his comrades, and a number of parades held annually in remembrance of the Rising, the Irish government discontinued its annual parade in Dublin in the early 1970s, and in 1976 it took the unprecedented step of proscribing (under the Offences against the State Act) a 1916 commemoration ceremony at the GPO organised by Sinn Féin and the Republican commemoration Committee.[73] A Labour Party TD, David Thornley, embarrassed the government (of which Labour was a member) by appearing on the platform at the ceremony, along with Máire Comerford, a survivor of the Rising, and Fiona Plunkett, sister of Joseph Plunkett.[74] This culminated in the complete ignoring of the seventy fifth anniversary of the Rising in 1991 by the State. With the advent of a Provisional IRA ceasefire and the beginning of what became known as the Peace Process during the 1990s, the official view of the Rising became more positive and in 1996 an eightieth anniversary commemoration at the Garden of Remembrance in Dublin was attended by the Taoiseach and leader of Fine Gael, John Bruton.[75] In 2005 the Taoiseach, Bertie Ahern, announced the government’s intention to resume the military parade past the GPO from Easter 2006, and to form a committee to plan centenary celebrations in 2016.[76]

90th Anniversary of the 1916 Rising

The 90th anniversary of the 1916 Easter Rising was commemorated by a military parade held in Dublin on Easter Sunday, 16 April 2006. The President of Ireland (Mary McAleese), the Lord Mayor of Dublin (Catherine Byrne), the Taoiseach (Bertie Ahern), members of the Irish Government and other invited guests reviewed the parade as it passed the General Post Office, headquarters of the Rising. The parade comprised some 2,500 personnel from the Irish Defence Forces (representing the Army, Air Corps, Naval Service, Irish Army Reserve and Naval Reserve), the Garda Síochána, Irish United Nations Veterans Association and members of the Organisation of National Ex-Servicemen and Women. The parade started at Dublin Castle and proceeded via Dame Street and College Green to the GPO, where a wreath was laid by the President. Earlier Ahern laid a wreath in Kilmainham Jail where the leaders of the rising were executed. The Taoiseach said the ceremonies were 'about discharging one generation's debt of honour to another.' The wreath-laying was attended by 92-year-old Father Joseph Mallin (son of ICA leader Michael Mallin), the only surviving child of the executed rebels, who was flown in from Hong Kong by the Irish Government for the event.[77] This was the first official commemoration held in Dublin since the early 1970s.

Notes

- ^ Department of the Taoiseach - Easter Rising

- ^ Max Caulfield (1995), The Easter Rebellion: Dublin 1916. Roberts Rinehart Publishers. ISBN-13: 978-1570980428

- ^ Encyclopaedia Britannica

- ^ BBC. 1910-16: The 'winning' of Home Rule to the Easter Rebellion: [1]

- ^ History.com Encyclopaedia

- ^ BBC: Blood sacrifice

- ^ Leaders and Men of the Easter Rising: Dublin 1916 Francis X. Martin 1967 p105

- ^ Sean Cronin, The McGarrity Papers, Anvil Books, 1972.

- ^ Eoin Neeson, Myths from Easter 1916, p. 67

- ^ F.S.L. Lyons, Parnell, Gill & Macmillan, FP 1977, ISBN 0 7171 3939 5 pg. 264

- ^ Eoin Neeson, Myths from Easter 1916, p. ?

- ^ The Green Flag, Kee, p.400-1. The IRA, Coogan, p.8-11

- ^ Kee, 170-2

- ^ Geraghty, Tony (2000). The Irish War: The Hidden Conflict Between the IRA and British Intelligence. Harper Collins. pp. 314–315. ISBN 978-0006386742.

- ^ Kee, 201-2

- ^ Kee, 181-2

- ^ Easter 1916: The Irish rebellion, Charles Townshend, 2005, page 18, The McGarrity Papers: revelations of the Irish revolutionary movement in Ireland and America 1900 – 1940, Sean Cronin, 1972, page 16, 30, The Provisional IRA, Patrick Bishop & Eamonn Mallie, 1988, page 23, The Secret Army: The IRA, Rv Ed, J Bowyer Bell 1997, page 9, The IRA, Tim Pat Coogan, 1984, page 31

- ^ The Fenians, Michael Kenny, The National Museum of Ireland in association with Country House, Dublin, 1994, ISBN 0 946172 42 0

- ^ Eoin Neeson, Myths from Easter 1916, p. ?

- ^ a b c Michael Foy & Brian Barton, The Easter Rising, J.H. Haynes & Co., ISBN 0 7509 3433 6

- ^ P. S. O’Hegarty writes that “of the seven founding members they were probably all Fenians, but at least four of them were.” While the Fenians used it naturally, it was not a political organisation, according to Hegarty; it remained faithful to its purpose: the Preservation and Cultivation of National Pastimes, though they did use it for the strengthening of national feeling generally. A History of Ireland Under the Union 1801 to 1922, pp. 611-612, P. S. O'Hegarty, Methuen & Co. Ltd, London

- ^ Myths from Easter 1916, Eoin Neeson, 2007, page 79, Easter 1916: The Irish Rebellion, Charles Townshend, 2005, page 41, The IRA, Tim Pat Coogan, 1970, page 33, The Irish Volunteers 1913-1915,F. X. Martin 1963, page 24, The Easter Rising, Michael Foy & Brian Barton, 2004, page 7, Myths from Easter 1916, Eoin Neeson, 2007, page 79, Victory of Sinn Féin, P.S. O’Hegarty, page 9-10, The Path to Freedom, Michael Collins, 1922, page 54, Irish Nationalism, Sean Cronin, 1981, page 105, A History of Ireland Under the Union, P. S. O’Hegarty, page 669, 1916: Easter Rising, Pat Coogan, page 50, Revolutionary Woman, Kathleen Clarke, 1991, page 44, The Bold Fenian Men, Robert Kee, 1976, page 203, The IRB: The Irish Republican Brotherhood from the League to Sinn Féin, Owen McGee, 2005, 353-354

- ^ F.S.L. Lyons, Ireland Since the Famine, Collins/Fontana, 1971; p. 341

- ^ MacNeill approved of armed resistance only if the British attempted to impose conscription on Ireland for the World War or if they launched a campaign of repression against Irish nationalist movements, in such a case he believed that they would have mass support. MacNeill's view was supported within the IRB, by Bulmer Hobson. Nevertheless, the IRB hoped either to win him over to their side (through deceit if necessary) or bypass his command altogether. Myths from Easter 1916, Eoin Neeson, 2007

- ^ Eoin Neeson, Myths from Easter 1916, p. ?

- ^ Brian Inglis, Roger Casement, HBJ, 1973, p. 299

- ^ "Desmond's Rising" Memoirs of Desmond FitzGerald; Liberties Press, Dublin, 1968 and 2006, pp.142-144.

- ^ Eoin Neeson, Myths from Easter 1916, p. ?

- ^ Michael Tierney, Eoin MacNeill, pp. 199, 214

- ^ Ó Broin, Leon, Dublin Castle & the 1916 Rising, p. 138

- ^ Ó Broin, Leon, Dublin Castle & the 1916 Rising, p. 79

- ^ Ó Broin, Leon, Dublin Castle & the 1916 Rising, pp. 81-87

- ^ McNally, Michael and Dennis, Peter, Easter Rising 1916: Birth of the Irish Republic, p. 39

- ^ McNally, Michael and Dennis, Peter, Easter Rising 1916: Birth of the Irish Republic, p. 40

- ^ Castles of Ireland: Part II - Dublin Castle at irelandforvisitors.com

- ^ McNally, Michael and Dennis, Peter, Easter Rising 1916: Birth of the Irish Republic, p. 41

- ^ Caulfield, Max, The Easter Rebellion, pp. 48-50

- ^ Foy and Barton, The Easter Rising, pp. 84-85

- ^ Foy and Barton, The Easter Rising, pp. 87-90

- ^ Caulfield, Max, the Easter Rebellion, pp. 54-55

- ^ Foy and Barton, The Easter Rising, pp. 192, 195

- ^ Caulfield, Max, The Easter Rebellion, p. 69

- ^ Agony at Easter:The 1916 Irish Uprising, Thomas M. Coffey, pages 38, 44, 155

- ^ Foy and Barton, pp. 197-198

- ^ Caulfield, Max, The Easter Rebellion, pp. 76-80

- ^ BBC News

- ^ Foy and Barton, The Easter Rising, page 325

- ^ Townshend, Easter 1916, page 273

- ^ Ó Broin, Leon, Dublin Castle & the 1916 Rising pp. 153-159

- ^ Townshend, Charles, Easter 1916: The Irish Rebellion p. 297

- ^ The Green Dragon No 4, Autumn 1997

- ^ The Impact of the 1916 Rising: Among the Nations, Edited by Ruán O’Donnell, Irish Academic Press Dublin 2008, ISBN 978 0 7165 2965, pg. 195-96

- ^ 1916 Easter Rising - Newspaper archive — from the BBC History website

- ^ The Impact of the 1916 Rising: Among the Nations, Edited by Ruán O’Donnell, Irish Academic Press Dublin 2008, ISBN 978 0 7165 2965, pg. 195-96

- ^ The Irish Republic, Dorothy Macardle, Victor Gollancz London 1937 (Hard Cover), pg.191

- ^ Agony at Easter: The 1916 Irish Uprising, Thomas M. Coffey, Pelican, Harmondsworth 1971, pg.259-60

- ^ Among his many books was his account of the Russo-Japanese War of 1904—5 and another on Japan’s occupation of Korea. In 1931 McKenzie became one of the earliest official biographers of Lord Beaverbrook. In 1916 he was a war correspondent for Canadian newspapers and War Illustrated, a British propaganda publication.

- ^ The Impact of the 1916 Rising: Among the Nations, Edited by Ruán O’Donnell, Irish Academic Press Dublin 2008, ISBN 978 0 7165 2965, pg. 196-97

- ^ The Impact of the 1916 Rising: Among the Nations, Edited by Ruán O’Donnell, Irish Academic Press Dublin 2008, ISBN 978 0 7165 2965, pg. 196-97

- ^ Under the Starry Plough, Frank Robbins, Academy Press (Dublin 1977), ISBN 0906187001, pg. 127

- ^ The Easter Rising, Brian Barton & Micheal Foy, Sutton Publishing Ltd. Gloucestershire, UK, ISBN 10: 0750934336, pg.206

- ^ The Impact of the 1916 Rising: Among the Nations, Edited by Ruán O’Donnell, Irish Academic Press Dublin 2008, ISBN 978 0 7165 2965, pg. 197

- ^ The Easter Rising, Brian Barton & Micheal Foy, Sutton Publishing Ltd. Gloucestershire, UK, ISBN 10: 0750934336

- ^ Foy & Barton cited in John Clarke Diary, National Library of Ireland, MS 10485

- ^ The Easter Rising, Brian Barton & Micheal Foy, Sutton Publishing Ltd. Gloucestershire, UK, ISBN 10: 0750934336, pg.203-9

- ^ The Impact of the 1916 Rising: Among the Nations, Edited by Ruán O’Donnell, Irish Academic Press Dublin 2008, ISBN 978 0 7165 2965, pg. 198

- ^ J. Bowyer Bell, The Secret Army: The IRA, page 27

- ^ Robert Kee The Green Flag: Ourselves Alone

- ^ RTÉ: 1966 News Items Relating to the 1916 Easter Rising Commemorations

- ^ O'Brien, Conor Cruise, States of Ireland Hutchinson, 1972 ISBN 0 09 113100 6, pp. 88, 99

- ^ Deane, Seamus, Wherever Green is Read, in Ní Dhonnchadha and Dorgan, Revising the Rising, Field Day, Derry, 1991 ISBN 0 946755 25 6, p. 91

- ^ Foster, Roy F., Modern Ireland 1600 – 1972, Penguin 1989 ISBN 978-0140132502, p. 484

- ^ Irish Times, 22 April 1976

- ^ Irish times, 26 April 1976

- ^ Reconstructing the Easter Rising, Colin Murphy, The Village, 16 February 2006

- ^ Irish Times, 22 October 2005

- ^ http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/in_pictures/4914362.stm

Bibliography

- Bell, J. Bowyer, The Secret Army: The IRA ISBN 1-85371-813-0

- Caulfield, Max, The Easter Rebellion, Dublin 1916 ISBN 1-57098-042-X

- Coogan, Tim Pat, 1916: The Easter Rising ISBN 0-304-35902-5

- Coogan, Tim Pat, The IRA (Fully Revised & Updated), HarperCollins, London, 2000, ISBN 0 00 653155 5

- De Rosa, Peter. Rebels: The Irish Rising of 1916. Fawcett Columbine, New York. 1990. ISBN 0-449-90682-5

- Foy, Michael and Barton, Brian, The Easter Rising ISBN 0-7509-2616-3

- Greaves, C. Desmond, The Life and Times of James Connolly

- Kee, Robert, The Green Flag ISBN 0-14-029165-2

- Kostick, Conor & Collins, Lorcan, The Easter Rising, A Guide to Dublin in 1916 ISBN 0-86278-638-X

- Lyons, F.S.L., Ireland Since the Famine ISBN 0-00-633200-5

- Martin, F.X. (ed.), Leaders and Men of the Easter Rising, Dublin 1916

- Macardle, Dorothy, The Irish Republic

- McNally, Michael and Dennis, Peter, Easter Rising 1916: Birth of the Irish Republic (2007), Osprey Publishing, ISBN 9781846030673

- Murphy, John A., Ireland In the Twentieth Century

- Neeson, Eoin, Myths from Easter 1916, Aubane Historical Society, Cork, 2007, ISBN 978 1 903497 34 0

- Ó Broin, Leon, Dublin Castle & the 1916 Rising, Sidgwick & Jackson, 1970

- Purdon, Edward, The 1916 Rising

- Townshend, Charles, Easter 1916: The Irish Rebellion

- The Memoirs of John M. Regan, a Catholic Officer in the RIC and RUC, 1909–48, Joost Augusteijn, editor, Witnessed Rising, ISBN 978-1-84682-069-4.

- Clayton, Xander: AUD, Plymouth 2007.

- Eberspächer, Cord/Wiechmann, Gerhard: "Erfolg Revolution kann Krieg entscheiden". Der Einsatz von S.M.H. LIBAU im irischen Osteraufstand 1916 ("Success revolution may decide war". The use of S.M.H. LIBAU in the Irish Easter rising 1916), in: Schiff & Zeit, Nr. 67, Frühjahr 2008, S. 2-16.

- Edited by Ruán O’Donnell, The Impact of the 1916 Rising: Among the Nations, Irish Academic Press Dublin 2008, ISBN 978 0 7165 2965

External links

- The 1916 Rising - an Online Exhibition. National Library of Ireland

- Essay on the Rising, by Garret FitzGerald

- Special 90th Anniversary supplement from The Irish Times

- Easter Rising 50th Anniversary audio & video footage from RTÉ (Irish public television)

- Easter Rising site and walking tour of 1916 Dublin

- News articles and letters to the editor in "The Age", 27 April 1916

- Press comments 1916-1996

- The 1916 Rising by Norman Teeling a ten-painting suite acquired by An Post for permanent display at the General Post Office (Dublin)