Obstetrics: Difference between revisions

Alejgonz 01 (talk | contribs) m improvement of article structure |

→Horizontal: fixed typo |

||

| Line 152: | Line 152: | ||

=====Horizontal===== |

=====Horizontal===== |

||

Compared to the other four vertical positions, this was certainly believed not instinctive and did not provide the labour with the necessary conditions to birth. Today we also know this position is inferior to the vertical positions as it increases the |

Compared to the other four vertical positions, this was certainly believed not instinctive and did not provide the labour with the necessary conditions to birth. Today we also know this position is inferior to the vertical positions as it increases the chance of fetal distress as malpresentation. It also decreases the space available in the pelvis, as the sacrum is unable to move backwards as it does naturally during labour. This method of childbirth developed after the introduction of the birthing stool and with the change in concentration of births in homes to hospitals. This position was used for women who had some difficulty in bringing the fetus to birth. Women only resorted to lying down especially on the bed because it would mean that the bedclothes would be soiled in the process. It was also avoided because it showed determination and was significant in showing difference from animals that lay down to give birth. This is similar to the resistance to giving birth on all fours.<ref name="Gelis122-134"/> |

||

A sixth position was used in some instances of a poor household, in the countryside and during the winter. It was a combination of the sitting position and laying position usually by a combination of small mattress and a fallen chair used as a backrest. This method was also greatly avoided and only used at the request of the mother because it required that the person helping birth the child—usually an obstetrician and not a midwife at this point—to crouch on the ground, working at nearly ground level.<ref name="Gelis122-134"/> |

A sixth position was used in some instances of a poor household, in the countryside and during the winter. It was a combination of the sitting position and laying position usually by a combination of small mattress and a fallen chair used as a backrest. This method was also greatly avoided and only used at the request of the mother because it required that the person helping birth the child—usually an obstetrician and not a midwife at this point—to crouch on the ground, working at nearly ground level.<ref name="Gelis122-134"/> |

||

Revision as of 20:19, 19 May 2015

Obstetrics (from the Latin obstare, "to stand by") is the health profession or medical specialty that deals with pregnancy, childbirth, and postpartum period [1] (including care of the newborn).[2] The midwife and the obstetrician are the professionals in obstetrics.

Main areas

Prenatal care

Prenatal care is important in screening for various complications of pregnancy. This includes routine office visits with physical exams and routine lab tests:

-

3D ultrasound of 3-inch (76 mm) fetus (about 14 weeks gestational age)

-

Fetus at 17 weeks

-

Fetus at 20 weeks

First trimester

- Complete blood count (CBC)

- Blood type

- General antibody screen (indirect Coombs test) for HDN

- Rh D negative antenatal patients should receive RhoGam at 28 weeks to prevent Rh disease.

- Rapid plasma reagin (RPR) to screen for syphilis

- Rubella antibody screen

- Hepatitis B surface antigen

- Gonorrhea and Chlamydia culture

- PPD for tuberculosis

- Pap smear

- Urinalysis and culture

- HIV screen

First trimester screening varies by country. Women are typically offered: Complete Blood Count (CBC), Blood Group and Antibody screening (Group and Save), Syphilis, Hepatitis B, HIV, Rubella immunity and urine microbiology and sensitivity to test for bacteria in the urine without symptoms. Additionally, women under 25 years of age are offered chlamydia testing via a urine sample, and women considered high risk are screened for Sickle Cell disease and Thalassemia. Women must consent to all tests before they are carried out. The woman's blood pressure, height and weight are measured, and her Body Mass Index (BMI) calculated. This is the only time her weight is recorded routinely. Her family history, obstetric history, medical history and social history are discussed.

Women usually have their first ultrasound scan at around twelve weeks. This is a trans-abdominal ultrasound. This is the scan from which the pregnancy is dated and the woman's estimated due date (or EDD) is worked out. At this scan, some NHS Trusts offer women the opportunity to have screening for Down's Syndrome. If it is done at this point, both the nuchal fold is measured and a blood test taken from the mother. The result comes back as an odd's risk for the fetus having Down's Syndrome. This is somewhere between 1:2 (high risk) to 1:100,000 (low risk). High risk women (who have a risk of greater than about 1:150) are offered further tests, which are diagnostic. These tests are invasive and carry a risk of miscarriage.

Genetic screening for downs syndrome (trisomy 21) and trisomy 18 the national standard in the United States is rapidly evolving away from the AFP-Quad screen for downs syndrome- done typically in the second trimester at 16–18 weeks. The newer integrated screen (formerly called F.A.S.T.E.R for First And Second Trimester Early Results) can be done at 10 plus weeks to 13 plus weeks with an ultrasound of the fetal neck (thick skin is bad) and two chemicals (analytes) PAPP-A and βHCG (pregnancy hormone level itself). It gives an accurate risk profile very early. A second blood screen at 15 to 20 weeks refines the risk more accurately. The cost is higher than an "AFP-quad" screen due to the ultrasound and second blood test but it is quoted to have a 93% pick up rate as opposed to 88% for the standard AFP/QS. This is an evolving standard of care in the United States.

Second trimester

- MSAFP/quad. screen (four simultaneous blood tests) (maternal serum AFP, inhibin A, estriol, & βHCG) - elevations, low numbers or odd patterns correlate with neural tube defect risk and increased risks of trisomy 18 or trisomy 21

- Ultrasound either abdominal or trannsvaginal to assess cervix, placenta, fluid and baby

- Amniocentesis is the national standard (in what country) for women over 35 or who reach 35 by mid pregnancy or who are at increased risk by family history or prior birth history.

The second trimester is when women start to see their midwife. Other than the booking appointment at around ten weeks and her ultrasound scan at around twelve weeks, she has not had much contact with health care professionals regarding her pregnancy. The actual schedule of appointments varies by NHS Trust, but the woman can expect to see her midwife around sixteen weeks. At this appointment, the results of the screening and tests carried out at her booking appointment is discussed. The woman's blood pressure is measured and a urinalysis done. The woman has the opportunity to ask questions. Some women ask to listen to the fetal heart at this appointment. This should not be routinely offered by the midwife, as at 16 weeks gestation, the heartbeat can be difficult to detect and some NHS Trusts do not scan at this point if the midwife can't hear the fetal heart.

At around twenty weeks, the woman has an anomaly scan. This trans-abdominal ultrasound scan checks on the anatomical development of the fetus. It is a detailed scan and checks all the major organs. As a consequence, if the fetus is not in a good position for the scan, the woman may be sent off for a walk and asked to return. At this scan, the position of the placenta is noted, to ensure it is not low. Cervical assessment is not routinely carried out.

Third trimester

- [Hematocrit] (if low, the mother receives iron supplements)

- Group B Streptococcus screen. If positive, the woman receives IV penicillin or ampicillin while in labor—or, if she is allergic to penicillin, an alternative therapy, such as IV clindamycin or IV vancomycin.

- Glucose loading test (GLT) - screens for gestational diabetes; if > 140 mg/dL, a glucose tolerance test (GTT) is administered; a fasting glucose > 105 mg/dL suggests gestational diabetes.

Most doctors do a sugar load in a drink form of 50 grams of glucose in cola, lime or orange and draw blood an hour later (plus or minus 5 minutes) ; the standard modified criteria have been lowered to 135 since the late 1980s

During the third trimester, women have further blood tests. Blood is taken for Full Blood Count (FBC) and a Group and Save to confirm her blood group, and as a further check for antibodies. This may routinely be done twice in the third trimester. A Glucose Tolerance Test (GTT) is done for women with risk factors for Gestational Diabetes. This includes women with a raised BMI, women of certain ethnic origins and women who have a first degree relative with diabetes. A vaginal swab for Group B Streptococcus (GBS) is only be taken for women known to have had a GBS-affected baby in the past, or for women who have had a urine culture positive for GBS during this pregnancy.

Women see the midwife more frequently as they progress through pregnancy. First time mothers, or mothers on the high risk care pathway, may see the midwife at around twenty four weeks, when the midwife offers to listen to the fetal heart. From twenty eight weeks, the midwife measures the symphysis fundal height (or SFH) to measure the growth of the abdomen. This is currently the best way to easily check fetal growth, but it is not perfect. At appointments, the midwife checks the woman's blood pressure and does a urinalysis. The midwife palpates the woman's abdomen to establish the lie, presentation and position of the fetus, and later, the engagement. The midwife offers to listen to the fetal heart.

From the woman's due date, the midwife may offer to do a stretch and sweep. This involves a vaginal examination, where the midwife assesses the cervix and attempts to sweep the membranes. This releases a hormone called prostaglandin, which helps the cervix prepare for labour.

Antenatal record

On the first visit to her obstetrician or midwife, the pregnant woman is asked to carry out the antenatal record, which constitutes a medical history and physical examination. On subsequent visits, the gestational age (GA) is rechecked with each visit.

The woman is given her notes at her booking appointment with the midwife. Following an assessment by the midwife, the woman's notes are put together and the woman is responsible for these notes. They are called her hand held records. The woman is advised to carry these with her at all times and to take them with her when she sees any healthcare professional. Following the anomaly scan, some NHS Trusts print out a customized growth chart. This takes in to account the woman's size and the size of any previous babies when decided what her 'normal range' is for SFH growth.

Symphysis-fundal height (SFH; in cm) should equal gestational age after 20 weeks of gestation, and the fetal growth should be plotted on a curve during the antenatal visits. The fetus is palpated by the midwife or obstetrician using the Leopold maneuver to determine the position of the baby. Blood pressure should also be monitored, and may be up to 140/90 in normal pregnancies. However, a significant rise in blood pressure, even below the 140/90 threshold, may be a cause for concern High blood pressure indicates hypertension and possibly pre-eclampsia if other symptoms are present. These may include swelling (edema), headaches, visual disturbances, epigastric pain and proteinurea.

Fetal screening is also used to help assess the viability of the fetus, as well as congenital problems. Genetic counseling is often offered for families who may be at an increased risk to have a child with a genetic condition. Amniocentesis, which is usually performed between 15 and 20 weeks,[3] to check for Down syndrome, other chromosome abnormalities or other conditions in the fetus, is sometimes offered to women who are at increased risk due to factors such as older age, previous affected pregnancies or family history. Amniocentesis, and other invasive investigations such as chorionic villus sampling, is not performed in the UK as frequently as it is in other countries, and in the UK, advanced maternal age alone is not an indication for such an invasive procedure.

Even earlier than amniocentesis is performed, the mother may undergo the triple test, nuchal screening, nasal bone, alpha-fetoprotein screening, Chorionic villus sampling, and also to check for disorders such as Down Syndrome. Amniocentesis is a prenatal genetic screening of the fetus, which involves inserting a needle through the mother's abdominal wall and uterine wall, to extract fetal DNA from the amniotic fluid. There is a risk of miscarriage and fetal injury with amniocentesis because it involves penetrating the uterus with the baby still in utero.

Imaging

Imaging is another important way to monitor a pregnancy. The mother and fetus are also usually imaged in the first trimester of pregnancy. This is done to predict problems with the mother; confirm that a pregnancy is present inside the uterus; estimate the gestational age; determine the number of fetuses and placentae; evaluate for an ectopic pregnancy and first trimester bleeding; and assess for early signs of anomalies.

X-rays and computerized tomography (CT) are not used, especially in the first trimester, due to the ionizing radiation, which has teratogenic effects on the fetus. No effects of magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) on the fetus have been demonstrated,[4] but this technique is too expensive for routine observation. Instead, obstetric ultrasonography is the imaging method of choice in the first trimester and throughout the pregnancy, because it emits no radiation, is portable, and allows for realtime imaging.

Ultrasound imaging may be done at any time throughout the pregnancy, but usually happens at the 12th week (dating scan) and the 20th week (detailed scan).

The safety of frequent ultrasound scanning has not be confirmed. Despite this, increasing numbers of women are choosing to have additional scans for no medical purpose, such as gender scans, 3D and 4D scans.

A normal gestation would reveal a gestational sac, yolk sac, and fetal pole. The gestational age can be assessed by evaluating the mean gestational sac diameter (MGD) before week 6, and the crown-rump length after week 6. Multiple gestation is evaluated by the number of placentae and amniotic sacs present.

Fetal assessments

Obstetric ultrasonography is routinely used for dating the gestational age of a pregnancy from the size of the fetus, the most accurate dating being in first trimester before the growth of the fetus has been significantly influenced by other factors. Ultrasound is also used for detecting congenital anomalies (or other fetal anomalies) and determining the biophysical profiles (BPP), which are generally easier to detect in the second trimester when the fetal structures are larger and more developed. Specialised ultrasound equipment can also evaluate the blood flow velocity in the umbilical cord, looking to detect a decrease/absence/reversal or diastolic blood flow in the umbilical artery.

Other tools used for assessment include:

- Fetal karyotype can be used for the screening of genetic diseases. This can be obtained via amniocentesis or chorionic villus sampling (CVS)

- Fetal hematocrit for the assessment of fetal anemia, Rh isoimmunization, or hydrops can be determined by percutaneous umbilical blood sampling (PUBS), which is done by placing a needle through the abdomen into the uterus and taking a portion of the umbilical cord.

- Fetal lung maturity is associated with how much surfactant the fetus is producing. Reduced production of surfactant indicates decreased lung maturity and is a high risk factor for infant respiratory distress syndrome. Typically a lecithin:sphingomyelin ratio greater than 1.5 is associated with increased lung maturity.

- Nonstress test (NST) for fetal heart rate

- Oxytocin challenge test

Complications and emergencies

The main emergencies include:

- Ectopic pregnancy is when an embryo implants in the uterine (Fallopian) tube or (rarely) on the ovary or inside the peritoneal cavity. This may cause massive internal bleeding.

- Pre-eclampsia is a disease defined by a combination of signs and symptoms that are related to maternal hypertension. The cause is unknown, and markers are being sought to predict its development from the earliest stages of pregnancy. Some unknown factors cause vascular damage in the endothelium, causing hypertension. If severe, it progresses to eclampsia, where seizures occur, which can be fatal. Preeclamptic patients with the HELLP syndrome show liver failure and Disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC). The only treatment is to deliver the fetus. Women may still develop pre-eclampsia following delivery.

- Placental abruption is where the placenta detaches from the uterus and the woman and fetus can bleed to death if not managed appropriately.

- Fetal distress where the fetus is getting compromised in the uterine environment.

- Shoulder dystocia where one of the fetus' shoulders becomes stuck during vaginal birth. There are many risk factors, including macrosmic (large) fetus, but many are also unexplained.

- Uterine rupture can occur during obstructed labor and endanger fetal and maternal life.

- Prolapsed cord can only happen after the membranes have ruptured. The umbilical cord delivers before the presenting part of the fetus. If the fetus is not delivered within minutes, or the pressure taken off the cord, the fetus dies.

- Obstetrical hemorrhage may be due to a number of factors such as placenta previa, uterine rupture or tears, uterine atony, retained placenta or placental fragments, or bleeding disorders.

- Puerperal sepsis is an ascending infection of the genital tract. It may happen during or after labour. Signs to look out for include signs of infection (pyrexia or hypothermia, raised heart rate and respiratory rate, reduced blood pressure), and abdominal pain, offensive lochia (blood loss) increased lochia, clots, diarrhea and vomiting.

Intercurrent diseases

In addition to complications of pregnancy that can arise, a pregnant woman may have intercurrent diseases, that is, other diseases or conditions (not directly caused by the pregnancy) that may become worse or be a potential risk to the pregnancy.

- Diabetes mellitus and pregnancy deals with the interactions of diabetes mellitus (not restricted to gestational diabetes) and pregnancy. Risks for the child include miscarriage, growth restriction, growth acceleration, fetal obesity (macrosomia), polyhydramnios and birth defects.

- Systemic lupus erythematosus and pregnancy confers an increased rate of fetal death in utero and spontaneous abortion (miscarriage), as well as of neonatal lupus.

- Thyroid disease in pregnancy can, if uncorrected, cause adverse effects on fetal and maternal well-being. The deleterious effects of thyroid dysfunction can also extend beyond pregnancy and delivery to affect neurointellectual development in the early life of the child. Demand for thyroid hormones is increased during pregnancy, and may cause a previously unnoticed thyroid disorder to worsen.

- Hypercoagulability in pregnancy is the propensity of pregnant women to develop thrombosis (blood clots). Pregnancy itself is a factor of hypercoagulability (pregnancy-induced hypercoagulability), as a physiologically adaptive mechanism to prevent post partum bleeding.[5] However, when combined with an additional underlying hypercoagulable states, the risk of thrombosis or embolism may become substantial.[5]

Childbirth care

Birthing positions

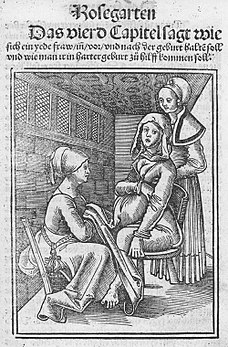

Historical positions

The process in the past of birthing a child began with very little preparation; improvisation was the rule of thumb. Dilation was determined mostly by touch and described by obstetricians and midwives very differently. Midwives would refer to the dilation of the cervix by comparing it to body parts, such as the palm of the hand, a finger, or even a fist. Obstetricians, usually men who had experience with using coins would refer to the dilation by relation to the size of currency.[6] The woman birthing the child would have topical remedies available to calm her nerves, ease pain and encourage her to deliver the baby hastily. The birthing mother was also able to decide her position of delivery as opposed to the standard laying down practice today. There were two main categories of positions, vertical and horizontal. These are expanded upon below.

Four positions are considered vertical and one horizontal:

Crouching

An instinctive position, this ensured full use of gravity to the mother’s advantage, and if the child appears suddenly, ensures safety from falling from a height and being injured. This position was most common when a woman was unattended and essentially without help. If necessary, the mother could watch her perineum and disengage the head of the baby herself. Common practice in many cultures apparently thought it essential to lay the newborn upon the ground as a connection to the earth and this position allowed the child to arrive with immediate contact with the ground. Downsides of this position are it requires great stamina and that the woman be fully nude below the waist.[6]

Kneeling

This position was common in the nineteenth century French provinces and by peasant women. The position called for knee protection and upper limb support, involving possibly a cushion and chair back or by being suspended between two chairs backs if alone.

Downsides to this position were that it caused back aches and cramps. Also, doctors considered it inferior due to the baby being received behind the mother. When a fetus underwent malpresentation (misalignment of the fetus, with the head not exiting the womb first) or when the womb was extremely protruding or comparatively large to the woman, she may have knelt on the ground with hands placed on the ground in front of her. Doctors of the enlightenment period thought this ‘on all fours’ position was too animalistic and indecent, and should be avoided.[6]

Sitting

A sitting position would be used in some cases for women who could not squat for extended periods of time. It was reinvented with the creation and use of the birthing stool. Contrary to the name, this could be either a stool or a chair with a large hole in the seat to use gravity to align and birth the child while supporting the weight of the mother. With the stool variation and the side of the bed position, another person would be used to support the mother’s upper body.[6]

Standing

Accidentally happening or deliberate, this position was rarely used due to the stamina required to do so as well as the tendency for mothers to teach their daughters how to birth otherwise. Daughters who hid their pregnancy could be caught standing and having their water break, instinctively these girls would brace themselves against a wall, table, chair and with the inability to move would deliver the baby there, allowing it to fall on the ground. This, of course, was extremely dangerous although in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, various textbooks show the persistence of the standing position with it persisting until the beginning of the twentieth century in some areas of France.[6]

Horizontal

Compared to the other four vertical positions, this was certainly believed not instinctive and did not provide the labour with the necessary conditions to birth. Today we also know this position is inferior to the vertical positions as it increases the chance of fetal distress as malpresentation. It also decreases the space available in the pelvis, as the sacrum is unable to move backwards as it does naturally during labour. This method of childbirth developed after the introduction of the birthing stool and with the change in concentration of births in homes to hospitals. This position was used for women who had some difficulty in bringing the fetus to birth. Women only resorted to lying down especially on the bed because it would mean that the bedclothes would be soiled in the process. It was also avoided because it showed determination and was significant in showing difference from animals that lay down to give birth. This is similar to the resistance to giving birth on all fours.[6]

A sixth position was used in some instances of a poor household, in the countryside and during the winter. It was a combination of the sitting position and laying position usually by a combination of small mattress and a fallen chair used as a backrest. This method was also greatly avoided and only used at the request of the mother because it required that the person helping birth the child—usually an obstetrician and not a midwife at this point—to crouch on the ground, working at nearly ground level.[6]

Birthing stool

The birthing stool –sometimes known as a birthing chair– was introduced in the seventeenth and the use of it was encouraged into the eighteenth century by the doctors and administrators who used it to control the child being birthed. The stool was usually very expensive and came in two types. The more expensive and heavier variety was used by wealthy families as a family heirloom— and typically was adorned with decoration or expensive materials. The second variety was used by village midwives as was lighter and portable so the midwife could carry it from home to home. It became popular in the French territory of (mostly German speaking) Alasace-Lorraine. At the beginning of the 19th century, the birthing stool’s use changed, as increased weight restricted its use to medical facilities. It, perhaps indirectly, evolved into the modern delivery table. This contributed to the transition to the modern day hospital setting.[7]

This was usually not the method of choice for many mothers, as the stool was very revealing, cold, and later became associated with the pain of childbirth. To decrease the draft on a woman’s genitals as she sat on the birthing stool, fabric was draped around the seat. This also provided a bit of privacy and respected the modesty of the mother.[8]

Induction

Induction is a method of artificially or prematurely stimulating labour in a woman. Reasons to induce can include pre-eclampsia, placental malfunction, intrauterine growth retardation,[9] and other various general medical conditions, such as renal disease. Induction may occur any time after 34 weeks of gestation if the risk to the fetus or mother is greater than the risk of delivering a premature fetus regardless of lung maturity.

Induction may be achieved via several methods:

- Pessary of Prostin cream, prostaglandin E2

- Intravaginal or oral administration of misoprostol

- Cervical insertion of a 30-mL Foley catheter

- Rupturing the amniotic membranes

- Intravenous infusion of synthetic oxytocin (Pitocin or Syntocinon)

Inducing labour may start with the midwife performing a stretch and sweep. This is a vaginal examination, where the midwife assesses the cervix and, if able to do so, sweeps the membranes—releasing prostaglandins, which physicians believe helps the cervix prepare for labour, and therefore brings on labour. If this is unsuccessful, the woman may be offered induction. This usually involves a vaginal examination where the cervix is assessed and given a Bishop's Score, and the insertion of prostaglandin as a pessary. Once the cervix is favourable (and it may take more than one dose of prostaglandin) and there is space on the labour ward, the woman is transferred to the labour ward for an Artificial rupture of membranes (ARM). Quite often, the woman is encouraged to mobilise, in the hope that she labour naturally. This may be for a couple of hours. If nothing happens, the woman is then commenced on an infusion of syntocinon. This is a synthetic form of the hormone oxytocin, which women naturally release during labour. If any step is successful, the woman continues to labour and does not move on to the next procedure.

Labor

During labor itself, the obstetrician or midwife may be called on to do a number of tasks. These tasks can include:

- Monitor the progress of labor, by reviewing the nursing chart, performing vaginal examination, and assessing the trace produced by a fetal monitoring device (the cardiotocograph)

- Accelerate the progress of labor by infusion of the hormone oxytocin

- Provide pain relief, either by nitrous oxide, opiates, or by epidural anesthesia done by anaesthestists, an anesthesiologist, or a nurse anesthetist.

- Surgically assisting labor, by forceps or the Ventouse (a suction cap applied to the fetus' head)

- Caesarean section, if there is an associated risk with vaginal delivery, as such fetal or maternal compromise supported by evidence and literature. Caesarean section can either be elective, that is, arranged before labor, or decided during labor as an alternative to hours of waiting. True "emergency" Cesarean sections include abruptio placenta, and are more common in multigravid patients, or patients attempting a Vaginal Birth After Caeserean section (VBAC).

Midwives care for women in labour and through the delivery. The midwife constantly assesses the woman and the fetus, and the progress of labour. As a minimum, in the first stage of labour, the midwife listens to the fetal heart for one minute every fifteen minutes, measure the woman's pulse hourly and record her blood pressure and temperature four hourly. She encourages the woman to empty her bladder every four hours, and measures and analyses each void. She offer an abdominal palpation and vaginal examination every four hours. In the second stage of labour, the fetal heart is ausculatated for one minute every five minutes, the pulse and blood pressure measured hourly, temperature every four hours, abdominal palpation and vaginal examination hourly, and the woman is encouraged to void frequently. These are all minimums. If the woman was on continuous fetal monitoring, the midwife would formally review this hourly. The midwife would refer to another health care practitioner if the labour deviated from the norm or if the woman requested an epidural. The midwife should discuss the woman's birth plan with her and explain the options regarding labour to the woman.

Postnatal care

Postnatal care is care provided to the mother following parturition.

A woman in the Western world who is delivering in a hospital may leave the hospital as soon as she is medically stable and chooses to leave, which can be as early as a few hours postpartum, though the average for spontaneous vaginal delivery (SVD) is 1–2 days, and the average caesarean section postnatal stay is 3–4 days.

During this time the mother is monitored for bleeding, bowel and bladder function, and baby care. The infant's health is also monitored.[10]

Certain things must be kept in mind as the physician proceeds with the post-natal care.

- General condition of the patient.

- Check for vital signs (pulse, blood pressure, temperature, respiratory rate, (pain) at times)

- Palor?

- Edema?

- Dehydration?

- Fundus (height following parturition, and the feel of the fundus) (Per abdominal examination)

- If an episiotomy or a C-section was performed, check for the dressing. Intact, pus, oozing, haematomas?

- Lochia (colour, amount, odour)?

- Bladder (keep the patient catheterized for 12 hours following local anaesthesia and 24–48 hours after general anaesthesia) ? (check for bladder function)

- Bowel movements?

- More bowel movements?

- Follow up with the neonate to check if they are healthy.

For women who have a hospital birth, the minimum hospital stay is six hours. Women who leave before this do so against medical advice. Women may choose when to leave the hospital. Full postnatal assessments are conducted daily whilst inpatient, or more frequently if needed. A postnatal assessment includes the woman's observations, general well being, breasts (either a discussion and assistance with breastfeeding or a discussion about lactation suppression), abdominal palpation (if she has not had a caesarean section) to check for involution of the uterus, or a check of her caesarean wound (the dressing doesn't need to be removed for this), a check of her perineum, particualarly if she tore or had stitches, reviewing her lochia, ensuring she has passed urine and had her bowels open and checking for signs and symptoms of a DVT. The baby is also be checked for jaundice, signs of adequate feeding, or other concerns. The baby has a nursery exam between six and seventy two hours of birth to check for conditions such as heart defects, hip problems, or eye problems.

In the community, the community midwife sees the woman at least until day ten. This does not mean she sees the woman and baby daily, but she cannot discharge them from her care until day ten at the earliest. Postnatal checks include neonatal screening test (NST, or heel prick test) around day five. The baby is weighed and the midwife plans visits according to the health and needs of mother and baby. They are discharged to the care of the health visitor.

Care of the newborn

At birth, the baby receives an Apgar score at, at the least, one minute and five minutes of age. This is a score out of 10 that assesses the baby on five different areas—each worth between 0 and 2 points. These areas are: colour, respiratory effort, tone, heart rate, and response to stimuli. The midwife checks the baby for any obvious problems, weighs the baby, and measure head circumference. The midwife ensures the cord has been clamped securely and the baby has the appropriate name tags on (if in hospital). Babies lengths are not routinely measured. The midwife performs these checks as close to the mother as possible and returns the baby to the mother quickly. Skin-to-skin is encouraged, as this regulates the baby's heart rate, breathing, oxygen saturation, and temperature—and promotes bonding and breastfeeding.

History

Prior to the 18th century, caring for pregnant women in Europe was confined exclusively to women, and rigorously excluded men. The expectant mother would invite close female friends and family members to her home to keep her company.[11] Skilled midwives managed all aspects of the labour and delivery. The presence of physicians and surgeons was very rare and only occurred once a serious complication had taken place and the midwife had exhausted all measures to manage the complication. Calling a surgeon was very much a last resort and having men deliver women in this era whatsoever was seen as offending female modesty.[12] [13]

Leading up to the 18th century

Obstetrics prior to the 18th and 19th centuries was not recognized on the same level of importance and professionalism as other medical fields, until about two hundred years ago it was not recognized as a medical practice. However, the subject matter and interest in the female reproductive system and sexual practice can be traced back to Ancient Greece[14] and even to Ancient Egypt.[15] Soranus of Ephesus sometimes is called the most important figure in ancient gynecology. Living in the late first century A.D. and early second century he studied anatomy and had opinions and techniques on abortion, contraception –most notably coitus interruptus– and birth complications. After the death of Soranus, techniques and works of gynecology declined but very little of his works were recorded and survived to the late 18th century when gynecology and obstetrics reemerged.[16]

18th century

The 18th century marked the beginning of many advances in European midwifery. These advances in knowledge were mainly regarding the physiology of pregnancy and labour. By the end of the century, medical professionals began to understand the anatomy of the uterus and the physiological changes that take place during labour. The introduction of forceps in childbirth also took place during the 18th century. All these medical advances in obstetrics were a lever for the introduction of men into an arena previously managed and run by women—midwifery.[17]

The addition of the male-midwife is historically a significant change to the profession of obstetrics. In the 18th century medical men began to train in area of childbirth and believed with their advanced knowledge in anatomy that childbirth could be improved. In France these male-midwives were referred to as "accoucheurs". This title was later on lent to male-midwives all over Europe. The founding of lying-hospitals also contributed to the medicalization and male-dominance of obstetrics. These lying-hospitals were establishments where women would come to have their babies delivered, which had prior been unheard of since the midwife normally came to home of the pregnant woman. This institution provided male-midwives or accoucheurs with an endless number of patients to practice their techniques on and also was a way for these men to demonstrate their knowledge.[18]

Many midwives of the time bitterly opposed the involvement of men in childbirth. Some male practitioners also opposed the involvement of medical men like themselves in midwifery, and even went as far as to say that men-midwives only undertook midwifery solely for perverse erotic satisfaction. The accoucheurs argued that their involvement in midwifery was to improve the process of childbirth. These men also believed that obstetrics would forge ahead and continue to strengthen.[12]

19th century

Even 18th century physicians expected that obstetrics would continue to grow, the opposite happened. Obstetrics entered a stage of stagnation in the 19th century, which lasted until about the 1880s.[11] The central explanation for the lack of advancement during this time was substantially due to the rejection of obstetrics by the medical community. The 19th century marked an era of medical reform in Europe and increased regulation over the medical profession. Major European institutions such as The College of Physicians and Surgeons considered delivering babies ungentlemanly work and refused to have anything to do with childbirth as a whole. Even when Medical Act 1858 was introduced, which stated that medical students could qualify as doctors, midwifery was entirely ignored. This made it nearly impossible to pursue an education in midwifery and also have the recognition of being a doctor or surgeon. Obstetrics was pushed to the side.[19]

By the late 19th century the foundation of modern day obstetrics and midwifery began develop. Delivery of babies by doctors became popular and readily accepted, but midwives continued to play a role in childbirth. Midwifery also changed during this era due to increased regulation and the eventual need for midwives to become certified. Many European countries by the late 19th century were monitoring the training of midwives and issued certification based on competency. Midwives were no longer uneducated in the formal sense.[20]

As midwifery began to develop so did the profession of obstetrics near the end of the century. Childbirth was no longer unjustifiably despised by the medical community as it once had been at the beginning of the century. But the specialty was still behind in its development stages in comparison to other medical specialities, and remained a generality in this era. Many male physicians would deliver children but very few would have referred to themselves as obstetricians. The end of the 19th century did mark a significant accomplishment in the profession with the advancements in asepsis and anesthesia, which paved the way for the mainstream introduction and later success of the Caesarean Section.[20][21]

Before the 1880s mortality rates in lying-hospitals would reach unacceptably high levels and became an area of public concern. Much of these maternal deaths were due to Puerperal fever, at the time commonly known as childbed fever. In the 1800s Dr. Ignaz Semmelweis noticed that women giving birth at home had a much lower incidence of childbed fever than those giving birth by physicians in lying-hospitals. His investigation discovered that washing hands with an antiseptic solution before a delivery reduced childbed fever fatalities by 90%.[22] So it was concluded that it was physicians who had been spreading disease from one laboring mother to the next. Despite the publication of this information, doctors still would not wash. It was not until the 20th century when advancements in aseptic technique and the understanding of disease would play a significant role in the decrease of maternal mortality rates among many populations.

History of obstetrics in America

The development of obstetrics as a practice for accredited doctors happened at the turn of the 18th century and thus was very differently developed in Europe and in the Americas due to the independence of many countries in the Americas from European powers. “Unlike in Europe and the British Isles, where midwifery laws were national, in America, midwifery laws were local and varied widely”.[23]

American surgeons are responsible for many of the advancements of Gynecology and Obstetrics –these two fields overlapped greatly as they both gained attention in the medical field– at the end of the nineteenth century through the development of such procedures as the ovariotomy. These procedures then were shared with European surgeons who replicated the surgeries. It should be noted that this was a period when antiseptic, aseptic or anesthetic measures were just being introduced to surgical and observational procedures and without these procedures surgeries were dangerous and often fatal. Following are two surgeons noted for their contributions to these fields include Ephraim McDowell and James Marion Sims.

Ephraim McDowell developed a surgical practice in 1795 and performed the first ovariotomy in 1809 on a 47-year-old widow who then lived on for thirty-one more years. He had attempted to share this with John Bell whom he had practiced under who had retired to Italy. Bell was said to have died without seeing the document but it was published by an associate in Extractions of Diseased Ovaria in 1825. By the mid-century the surgery was both successfully and unsuccessfully being performed. Pennsylvanian surgeons the Attlee brothers made this procedure very routine for a total of 465 surgeries–John Attlee performed 64 successfully of 78 while his brother William reported 387– between the years of 1843 and 1883. By the middle of the nineteenth century this procedure was successfully performed in Europe by English surgeons Sir Spencer Wills and Charles Clay as well as French surgeons Eugène Koeberlé, Augeste Nélation and Jules Peau.[24]

J. Marion Sims was the surgeon responsible for being the first treating a vesicovaginal fistula [24]–a condition linked to many caused mainly by prolonged pressing of the fetus against the pelvis or other causes such as rape, hysterectomy, or other operations– and also having been doctor to many European royals and the 20th President of the United States James A. Garfield after he had been shot. Sims does have a controversial medical past. Under the beliefs at the time about pain and the prejudice towards African people, he had practiced his surgical skills and developed skills on slaves.[25] These women were the first patients of modern gynecology. One of the women he operated on was named Anarcha, the woman he first treated for a fistula.[26]

Historical role of gender

Women and men inhabited very different roles in natal care up to the 18th century. The role of a physician was exclusively held by men who went to university, an overly male institution, who would theorize anatomy and the process of reproduction based on theological teaching and philosophy. Many beliefs about the female body and menstruation in the 17th and 18th centuries were inaccurate; clearly resulting from the lack of literature about the practice.[27] Many of the theories of what caused menstruation prevailed from Hippocratic philosophy.[28] Midwives of this time were those assisted in the birth and care of both born and unborn children, and as the name suggests this position held mainly by women.

During the birth of a child, men were rarely present. Women from the neighborhood or family would join in on the process of birth and assist in many different ways. The one position where men would help with the birth of a child would be in the sitting position, usually when performed on the side of a bed to support the mother.[29]

Men were introduced into the field of obstetrics in the nineteenth century and resulted in a change of the focus of this profession. Gynecology directly resulted as a new and separate field of study from obstetrics and focused on the curing of illness and indispositions of female sexual organs. This had some relevance to some conditions as menopause, uterine and cervical problems, and childbirth could leave the mother in need of extensive surgery to repair tissue. But, there was also a large blame of the uterus for completely unrelated conditions. This led to many social consequences of the nineteenth century.[27]

See also

- Obstetrics and gynaecology

- Childbirth and obstetrics in antiquity

- Gynecologist

- Henry Jacques Garrigues, who introduced antiseptic obstetrics to North America

- Maternal-fetal medicine

- Obstetric ultrasonography

- Puerperum

References

This article needs additional citations for verification. (October 2008) |

- ^ Miller-Keane Encyclopedia & Dictionary of Medicine, Nursing, and Allied Health. Saunders. 2005. ISBN 9781416026044.

- ^ International Confederation of Midwives. International Definition of Midwife

- ^ http://www.medicinenet.com/amniocentesis/article.htm

- ^

Ibrahim A. Alorainy, Fahad B. Albadr, Abdullah H. Abujamea (2006). "Attitude towards MRI safety during pregnancy". Ann Saudi Med. 26 (4): 306–9. PMID 16885635.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Page 264 in: Gresele, Paolo (2008). Platelets in hematologic and cardiovascular disorders: a clinical handbook. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-88115-3.

- ^ a b c d e f g Gelis, Jacues. History of Childbirth. Boston: Northern University Press, 1991: 122-134

- ^ Gelis, Jacues. History of Childbirth. Boston: Northern University Press, 1991: 129-130

- ^ Gelis, Jacues. History of Childbirth. Boston: Northern University Press, 1991: 130

- ^ Wagner, Marsden. Born in the USA: How a Broken Maternity System Must Be Fixed to Put Women and Children First. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2006. Print.

- ^ "With Women, Midwives Experiences: from Shiftwork to Continuity of Care, David Vernon, Australian College of Midwives, Canberra, 2007 ISBN 978-0-9751674-5-8, p17f

- ^ a b Gelis, Jacues. History of Childbirth. Boston: Northern University Press, 1991: 96-98

- ^ a b Bynum, W.F., & Porter, Roy, eds. Companion Encyclopedia of the History of Medicine. London and New York: Routledge, 1993: 1050-1051.

- ^ Carr, Ian., “University of Manitoba: Women’s Health.” May 2000, accessed May 20, 2012, http://www.neonatology.org/pdf/dyingtohaveababy.pdf

- ^ Hufnagel, Glenda Lewin. A History of Women's Menstruation from Ancient Greece to the Twenty-First Century: Psychological, Social, Medical, Religious, and Educational Issues. Lewiston: Edwin Mellen Press, 2012. 15.

- ^ McGrew, Roderick E. Encyclopedia of Medical History. New York: McGraw-Hill Book Company, 1985. 122.

- ^ McGrew, Roderick E. Encyclopedia of Medical History. New York: McGraw-Hill Book Company, 1985. 123.

- ^ Bynum, W.F., & Porter, Roy, eds. Companion Encyclopedia of the History of Medicine. London and New York: Routledge, 1993: 1051-1052.

- ^ Encyclopedia of Children and Childhood in History and Society, “Obstetrics and Midwifery.” accessed May 21, 2012, http://www.faqs.org/childhood/Me-Pa/Obstetrics-and- Midwifery.html

- ^ Bynum, W.F., & Porter, Roy, eds. Companion Encyclopedia of the History of Medicine. London and New York: Routledge, 1993: 1053-1055.

- ^ a b Drife, J., “The start of life: a history of obstetrics,” Postgraduate Medical Journal 78 (2002): 311-315, accessed May 21, 2012. doi: 10.1136/pmj.78.919.311.

- ^ Low, James., “Caesarean section-past and present,” Journal of obstetrics and gynecology Canada 31, no. 12 (2009): 1131-1136, accessed May 20, 2012. http://www.sogc.org/jogc/abstracts/full/200912_Obstetrics_2.pdf

- ^ Caplan, Caralee E. (1995). "The Childbed Fever Mystery and the Meaning of Medical Journalism". McGill Journal of Medicine. 1 (1).

- ^ Roth, Judith. “Pregnancy & Birth: The History of Childbearing Choices in the United States.”Human Service Solutions. Accessed February 14th, 2014. http://www.ourbodiesourselves.org/

- ^ a b McGrew, Roderick E. Encyclopedia of Medical History. New York: McGraw-Hill Book Company, 1985. 125.

- ^ International Wellness Foundation.” Dr. J Marion Sims: The Father of Modern Gynecology.” February 12th, 2014. www.mnwelldir.org/docs/history/biographies/marion_sims.htm

- ^ International Wellness Foundation. “Anarcha The Mother of Gynecology.” March 28th, 2014. www.mnwelldir.org/docs/history/biographies/marion_sims.htm

- ^ a b McGrew, Roderick E. Encyclopedia of Medical History. New York: McGraw-Hill Book Company, 1985. 123-125.

- ^ Hufnagel, Glenda Lewin. A History of Women's Menstruation from Ancient Greece to the Twenty-First Century: Psychological, Social, Medical, Religious, and Educational Issues. Lewiston: Edwin Mellen Press, 2012. 16.

- ^ Gelis, Jacues. History of Childbirth. Boston: Northern University Press, 1991: 130.

Further reading

- Lane, J (July 1987). "A provincial surgeon and his obstetric practice: Thomas W. Jones of Henley-in-Arden, 1764-1846". Medical History. 31 (3): 333–48. doi:10.1017/s0025727300046895. PMC 1139744. PMID 3306222.

- Stockham, Alice B. Tokology. A Book for Every Woman. o.O., (Kessinger Publishing) o.J. Reprint of Revised Edition Chicago, Alice B. Stockham & Co. 1891 (first edition 1886). ISBN 1-4179-4001-8