1971 in the Vietnam War

| 1971 in the Vietnam War | |||

|---|---|---|---|

← 1970 1972 → | |||

Fire Support Base Lolo falls to PAVN forces during Operation Lam Son 719 | |||

| |||

| Belligerents | |||

|

Anti-Communist forces: |

Communist forces: | ||

| Strength | |||

|

South Vietnam: 1,046,250 | |||

| Casualties and losses | |||

|

US: 2,357 killed[1] South Vietnam: Killed | |||

January

- 1 January

U.S. military personnel in South Vietnam totaled 334,600 on 31 December 1970.[2]

- 5 January

The United States Congress adopted the revised Cooper-Church Amendment which prohibited the introduction of U.S. ground troops or advisers into Cambodia and declared that U.S. aid to Cambodia should not be considered a commitment to the defense of Cambodia.[3]

- 6 January

United States Secretary of Defense Melvin Laird said that the "Vietnamization" of the war was running ahead of schedule and that the combat mission of the U.S. troops would end in summer 1971.[4]

- 7 January

The last herbicide spraying by the United States to defoliate forests in South Vietnam and kill crops used to feed communist soldiers and supporters was carried out in Ninh Thuan province. Operation Ranch Hand was finished.[5]

- 17 January

300 South Vietnamese paratroopers with U.S. air support and advisers raided a suspected camp holding American prisoners of war in Cambodia. No POWs were in the camp but 30 communist soldiers were captured.[6]

February

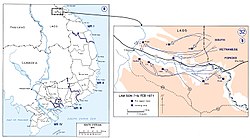

- 8 February- 25 March

Operation Lam Son 719 (Vietnamese: Chiến dịch Lam Sơn 719 or Chiến dịch đường 9 – Nam Lào) was an invasion by 20,000 soldiers of the armed forces of South Vietnam of southeastern Laos. The objective of the operation was the disruption of the Ho Chi Minh Trail (the Truong Son Road to North Vietnam) which supplied communist armed forces in South Vietnam. Although claiming victory, the South Vietnamese army (ARVN) withdrew from Laos in disorder and suffered 9,000 casualties. The U.S. supported the operation and had 253 soldiers killed and many helicopters destroyed.[7]

- 10 February

In Operation Lam Song 719, an armoured column of the ARVN reached Ban Dong, 20 kilometers inside Laos and one half the distance to Tchepone, the objective of the invasion. The route, Highway 9, was only barely passable and the advance stalled. The North Vietnamese concentrated their resistance against a number of small bases established in Laos to support the operation.[8]

March

- 1 March

A bomb exploded in the United States Capitol building at 1:32 a.m., injuring nobody but causing $300,000 in damage. The Weather Underground took credit for the bombing which was in protest of the invasion of Laos.[9]

- 6 March

In Operation Lam Son 719, an airborne operation began against Tchepone, Laos, the objective of the invasion of Laos by the South Vietnamese army with American support. Operation Lam Son 719 was the largest airborne assault of the Vietnam War utilizing on this date 120 Huey helicopters to transport two battalions. Tchepone was captured without major resistance.[10]

- 9 March

President Thieu of South Vietnam ordered the withdrawal of South Vietnamese troops from Laos. He ignored the recommendation of U.S. Commander General Creighton Abrams that South Vietnam reinforce its troops in Laos and hold its position. The withdrawal became a disaster with South Vietnam suffering heavy casualties.[11]

- 15 March

North Vietnamese artillery began to shell Khe Sanh Combat Base, the U.S.'s base for support of South Vietnam's invasion of Laos.[12]

- 23 March

National Security Adviser Kissinger admitted to President Nixon that Lam Son 719 "comes out as clearly not a success." The failure of Lam Son 719 was called by one scholar "the military turning point of the war."[13]

- 25 March

In Operation Lam Son 719, most surviving South Vietnamese soldiers had crossed the border back into South Vietnam and fighting in Laos ceased.[14]

- 28 March

Several dozen North Vietnamese sappers infiltrated Fire Support Base Mary Ann in Quang Tin province and killed 30 American soldiers. Mary Ann was scheduled to be turned over the South Vietnamese and the U.S. forces withdrawn. Several American officers were demoted or reprimanded for "substandard performance."[15]

- 29 March

The jury at a military courts-martial convicted Lt. William Calley of the premeditated murder of 22 Vietnamese civilians during the My Lai massacre of 1968. Calley was the only soldier convicted for his role in the massacre.[16]

- 30 March

A confidential U.S. Army directive ordered the interception and confiscation of anti-Vietnam War and other dissident material being sent to U.S. military personnel in South Vietnam.[17]

- 31 March

Lt. William Calley was convicted of murder and sentenced to life imprisonment and hard labor at Fort Leavenworth for his role in the My Lai massacre.[16]

April

- 3 April

President Nixon ordered Lt. Calley, convicted and sentenced to life imprisonment for his role in the My Lai massacre, to be transferred from Leavenworth prison to house arrest.[18]

- 7 April

Khe Sanh Combat Base, activated to provide U.S. support to the Lam Song 719 operation, was abandoned once again.[19]

- 23 April

Vietnam veterans threw away over 700 medals on the west steps of the United States Capitol building in Washington to protest the Vietnam War.[20] The next day, antiwar organizers claimed that 500,000 marched, making this the largest demonstration since the November 1969 march.[21]

- 30 April

Catholic Priest Philip Berrigan and seven others were indicted for planning to kidnap National Security Adviser Henry Kissinger and to blow up government buildings.[22]

May

- 3 May

15,000 soldiers and police arrested more than 7,000 persons protesting the Vietnam War in Washington.[23]

- 5 May

1146 protesters against the Vietnam War were arrested on the U.S. Capitol grounds in Washington trying to shut down the U.S. Congress. This brought the total arrested during the 1971 May Day Protests to over 12,000.[24]

- 13 May

The peace talks in Paris between North Vietnam, South Vietnam, the National Liberation Front (Viet Cong) and the United States enter their fourth year. Little or no progress has been made.[25]

- 31 May

National Security Advisor Henry Kissinger in secret peace negotiations with North Vietnam in Paris, France introduced a new proposal. He proposed a U.S. withdrawal from South Vietnam, a cease fire in place, and an exchange of prisoners. The cease fire in place was a key concession because it would allow North Vietnamese soldiers to remain in South Vietnam at least temporarily.[26]

June

- 24 June

The Mansfield Amendment, authored by Senator Mike Mansfield, was adopted by Congress. The amendment urged withdrawing American troops from South Vietnam at "the earliest practical date"—the first time in U.S. history that Congress had called for the end of a war.[23]

- 27 June

North Vietnam negotiators Le Duc Tho and Xuan Thuy responded to Kissinger's 31 May proposal with a nine-point "bargaining proposal." This was the first time that the North Vietnamese had indicated a willingness to negotiate rather than presenting unilateral demands.[13]

July

- 17 July

The Politburo of North Vietnam instructed its negotiators in Paris not to make any further concessions to the United States.[27]

- 26 July

Kissinger announced that the United States was prepared to provide $7.5 billion in aid to Vietnam, of which $2.5 billion could go to North Vietnam, and to withdraw all American forces within nine months.[13]

August

- 12 August

General Duong Van Minh ("Big Minh") submitted evidence to the American Embassy in Saigon that President Thieu was rigging the Presidential election scheduled for October.[28]

- 17 August

The American Embassy in Saigon informed Washington that if President Thieu persisted in his efforts to make the upcoming Presidential election a charade, it might cause "growing political instability in South Vietnam."[29]

- 20 August

General Minh ("Big Minh") withdrew as a candidate for President in the upcoming Presidential election in South Vietnam. Minh said "I cannot put up with a disgusting farce that strips away all the people's hope of a democratic regime."[29]

Lt. William Calley's life sentence for his role in the My Lai massacre was reduced to 20 years.Calley would serve only three and one-half years of his sentence before being paroled.[30]

- 23 August

General Nguyen Cao Ky withdrew his candidacy for President in the upcoming election. Incumbent President Thieu was the only candidate remaining in the election.[29]

- 20 August - 3 December 0

Operation Chenla II was a major military operation conducted by the Cambodian military (then known as FANK) during the Cambodian Civil War. The Cambodian military failed to dislodge the communist North Vietnamese Army and Viet Cong from territory and suffered heavy casualties.

September

- 5 September - 8 October

Operation Jefferson Glenn was the last major ground operation in which U.S. troops participated in the Vietnam War. Three battalions of the 101st Airborne patrolled the area west of the city of Hue, called the "rocket belt," to try to prevent communist rocket attacks. The Americans were gradually replaced by soldiers of the South Vietnamese army. The Americans and South Vietnamese claimed to have inflicted 2,026 casualties on the Viet Cong and North Vietnamese.[31]

October

- 2 October

A nationwide election for President was held in South Vietnam. Incumbent President Thieu garnered 94.3 percent of the vote. All of Thieu's opponents had dropped out of the race.[32]

- 11 October

Several U.S. soldiers at Firebase Pace near the Cambodian border refused to undertake a patrol outside the perimeter of the firebase. The combat refusal was widely reported by the media as was a letter signed by 65 American soldiers at Firebase Pace to U.S. Senator Edward M. Kennedy protesting that they were being ordered to participate in offensive combat operations despite U.S. policy to the contrary.[33]

- 12 October

President Nixon announced that "American troops are now in a defensive position...the offensive activities of search and destroy are now being undertaken by the South Vietnamese"[34]

- 16 October

Prime Minister Lon Nol of Cambodia suspended the Cambodian National Assembly and announced that he would run the country by executive decree. Lon Nol said that "the sterile game of democracy" was hindering the Cambodian government's fight against the communist forces of the Khmer Rouge and North Vietnamese.[33]

November

- 2 November

A U.S. Senate sub-committee issued a 300-page report "corruption, criminality, and moral compromise" at U.S. Post Exchanges in South Vietnam.[35]

December

- 26 December

President Nixon ordered the initiation of Operation Proud Deep Alpha, an intensive five-day bombing campaign against military targets in North Vietnam just north of they border above the 17th parallel of latitude.[36]

- 31 December

The number of U.S. military personnel in South Vietnam totaled 156,800, down from more than 500,000 three years earlier.[37]

Year in numbers

| Armed Force | Strength | KIA | Reference | Military costs - 1971 | Military costs in 2024 US$ | Reference | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1,046,250 | [38] | ||||||

| 156,800 | [1] | ||||||

| 45,700 | [38][39] | ||||||

| 6000 | [38] | ||||||

| 2000 | [38] | ||||||

| 50 | [38] | ||||||

| 100 | [38] | ||||||

Notes

- ^ a b United States 2010

- ^ "Vietnam War Timeline: 1969-1970" http://www.vietnamgear.com/war1969.aspx, accessed 12 Aug 2015

- ^ CQ Almanac, https://library.cqpress.com/cqalmanac/document.php?id=cqal70-1292681, accessed 10 Aug 2015

- ^ Daugherty, Leo, (2011), The Vietnam War" Day by Day, London: Chartwell Books, p. 177

- ^ Buckingham, Jr., William A. (1982) Operation Ranch Hand: The U.S. Air Force and Herbicides, 1961-1971 Washington, D.C.: Office of Air Force History, p. 175

- ^ Bowman, p. 275.

- ^ Fulghum, David and Maitland, Terrence (1984), South Vietnam on Trial, Boston: Boston Publishing Company, pp. 70-90

- ^ Fulghum and Maitland, p. 75

- ^ Mar 01, 1971, "This Day in History",http://www.history.com/this-day-in-history/bomb-explodes-in-capitol-building, accessed 12 Aug 2015

- ^ Fulghum and Maitland, p. 85

- ^ Fulghum and Maitland, p. 86-90

- ^ Fulghum and Maitland, p. 92

- ^ a b c Asselin, p. 28

- ^ Fulghum and Maitland, p. 90

- ^ Fulghum and Maitland pg. 7-9

- ^ a b - 1971 Year in Review: Calley Trial, Foreign Affairs - http://www.upi.com/Audio/Year_in_Review/Events-of-1971/Calley-Trial%2C-Foreign-Affairs/12295509436546-8/

- ^ "Vietnam War Timeline", "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2007-04-16. Retrieved 2007-04-17.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link), accessed 1 Sep 2015 - ^ Bowman, John S. Ed. (1985), The World Almanac of the Vietnam War, New York: Pharos Books, p. 274

- ^ Fulghum and Maitland, p. 96

- ^ "Veterans Discard Medals In War Protest At Capitol", New York Times, April 24, 1971, P. 1

- ^ "Reports of Its Death Have Been Greatly Exaggerated", James Buckley, New York Times, April 25, 1971, P. E1

- ^ Summers, Jr., Harry G. (1985), Vietnam War Almanac, New York: Facts on File Publications, p. 54

- ^ a b "Vietnam War Timeline", "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2007-04-16. Retrieved 2007-04-17.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link), accessed 2 Sep 2015 - ^ Protesters Fail to Stop Congress, Police Seize 1,146", James M. McNaughton, New York Times, May 6, 1971, P. 1

- ^ Bowman, p. 283

- ^ Asselin, Pierre (2002), A Bitter Piece: Washington, Hanoi, and the Making of the Paris Agreement, Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, pp. 27-28

- ^ Asselin, pg. 29

- ^ Fulghum and Maitland, p. 104

- ^ a b c Fulgrum and Maitland, p. 104

- ^ "William Calley Court Martial: 1970," Encyclopidia.com, http://www.encyclopedia.com/topic/William_Calley.aspx, accessed 11 Sep 2015

- ^ Tucker, Spencer C. (1998), The Encyclopedia of the Vietnam War, Oxford: Oxford University Press, p. 194

- ^ Fulghum and Maitland, p. 107

- ^ a b Bowman, p. 291

- ^ Fulghum and Maitland, p. 25

- ^ "Vietnam War Timeline," http://www.landscaper.net/timelin.htp, accessed 2 Sep 2015

- ^ Asselin, p. 29

- ^ "Vietnam War Timeline: 1971-1972, http://www.vietnamgear.com/war1971.aspx, accessed 12 Aug 1975

- ^ a b c d e f Template:HCMC War Remnants Museum

- ^ Leepson & Hannaford 1999, p. 209

Bibliography

- Asselin, Pierre (2002), A Bitter Peach: Washington, Hanoi, and the Making of the Paris Agreement, Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press. ISBN 0-8078-5417-4.

- Fulghum, David and Maitland, Terrence (1984), The Vietnam Experience: South Vietnam on Trial, Mid-1970 to 1972, Boston: Boston Publishing Company. ISBN 0-939526-10-7.

- United States, Government (2010). "Statistical information about casualties of the Vietnam War". National Archives and Records Administration. Archived from the original on 26 January 2010. Retrieved March 6, 2010.

{{cite web}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help); Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help)