Buddy Guy

Buddy Guy | |

|---|---|

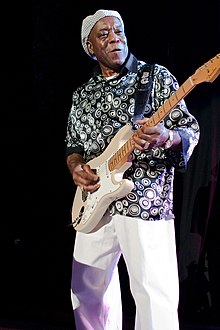

Buddy Guy performing in 2008 | |

| Background information | |

| Birth name | George Guy |

| Born | July 30, 1936 Lettsworth, Louisiana, U.S.[1] |

| Genres | Chicago blues, blues, electric blues, blues rock |

| Occupation(s) | Musician, songwriter, guitarist |

| Instrument(s) | Guitar, vocals |

| Years active | 1953–present |

| Labels | RCA, Cobra, Chess, Delmark, Silvertone, MCA, Atlantic, MPS, Charly, Zomba Group, Jive, Vanguard, JSP, Rhino, Purple Pyramid, Flyright, AIM Recording, Alligator, Blues Ball Records |

| Website | www |

George "Buddy" Guy (born July 30, 1936)[2] is an American blues guitarist and singer. He is an exponent of Chicago blues and has influenced guitarists including Eric Clapton, Jimi Hendrix, Jimmy Page, Keith Richards, Stevie Ray Vaughan, Jeff Beck, Gary Clark Jr. and John Mayer. In the 1960s, Guy played with Muddy Waters as a house guitarist at Chess Records and began a musical partnership with the harmonica player Junior Wells.

Guy was ranked 23rd in Rolling Stone magazine's "100 Greatest Guitarists of All Time".[3] His song "Stone Crazy" was ranked 78th in the Rolling Stone list of the "100 Greatest Guitar Songs of All Time".[4] Clapton once described him as "the best guitar player alive".[5] In 1999, Guy wrote the book Damn Right I've Got the Blues, with Donald Wilcock.[6] His autobiography, When I Left Home: My Story, was published in 2012.[7]

Early life

Guy was born and raised in Lettsworth, Louisiana.[1] His parents were sharecroppers and as a child, Guy would pick cotton for $2.50 per 100 pounds.[8] He began learning to play the guitar using a two-string diddley bow he made. Later he was given a Harmony acoustic guitar which, decades later in Guy's lengthy career, was donated to the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame.[citation needed]

Career

In the mid-1950s Guy began performing with bands in Baton Rouge, including with Big Papa Tilley and Raful Neal.[9] While living there, he worked as a custodian at Louisiana State University.[1] In 1957, he recorded two demos for a local DJ in Baton Rouge for Ace Records, but they were not issued at the time.[10]

Soon after moving to Chicago on September 25, 1957,[1] Guy fell under the influence of Muddy Waters. In 1958, a competition with West Side guitarists Magic Sam and Otis Rush gave Guy a record contract. Soon afterwards he recorded for Cobra Records. During his Cobra sessions, he teamed up with Ike Turner who helped him make his second record, "You Sure Can't Do" / "This Is The End", by backing him on guitar and composing the latter.[11][12] After two releases from Cobra's subsidiary, Artistic, Guy signed with Chess Records.[13]

Guy's early career was impeded by his record company, Chess Records, his label from 1959 to 1968, which refused to record Guy playing in the novel style of his live shows. Leonard Chess, Chess Records founder, denounced Guy's playing as "just making noise.”[14] In the early 1960s, Chess tried recording Guy as a solo artist with R&B ballads, jazz instrumentals, soul and novelty dance tunes, but none of these recordings was released as a single. Guy's only Chess album, I Left My Blues in San Francisco, was released in 1967. Most of the songs belong stylistically to the era's soul boom, with orchestrations by Gene Barge and Charlie Stepney. Chess used Guy mainly as a session guitarist to back Muddy Waters, Howlin' Wolf, Little Walter, Sonny Boy Williamson, Koko Taylor and others. As late as 1967, Guy worked as a tow truck driver while playing clubs at night.[8]

During his tenure with Chess, Guy recorded sessions with Junior Wells for Delmark Records under the pseudonym Friendly Chap in 1965 and 1966.[15] In 1965, he participated in the European tour American Folk Blues Festival.[16]

He appeared onstage at the March 1969 "Supershow" in Staines, England, which also included Eric Clapton, Led Zeppelin, Jack Bruce, Stephen Stills, Buddy Miles, Glenn Campbell, Roland Kirk, Jon Hiseman, and the Misunderstood. In 1972, he established The Checkerboard Lounge, with partner L.C. Thurman.[17]

Guy's career was revived during the blues revival of the late 1980s and early 1990s. His resurgence was sparked by Clapton's request that Guy be part of the "24 Nights" all-star blues guitar lineup at London's Royal Albert Hall.[17] Guy subsequently signed with Silvertone Records and recorded his mainstream breakthrough album Damn Right, I've Got the Blues in 1991.

Guy had a small role in the 2009 crime film In the Electric Mist as Sam "Hogman" Patin.[18]

As of 2019, Guy still performs at least a hundred and thirty nights a year,[8] including a month of shows each January at his Chicago blues club, Buddy Guy's Legends.[19][20]

In 2015, Alan Harper, a British blues fan, published the book Waiting for Buddy Guy: Chicago Blues at the Crossroads.[21]

Buddy Guy was among hundreds of artists whose material was reportedly destroyed in the 2008 Universal fire.[22]

Artistry and legacy

Music style

This section of a biography of a living person does not include any references or sources. (May 2018) |

While Guy's music is often labelled Chicago blues, his style is unique and separate. His music can vary from the most traditional, deepest blues to a creative, unpredictable and radical gumbo of the blues, avant rock, soul and free jazz that changes with each performance.

As the New York Times music critic Jon Pareles noted in 2005,

Mr. Guy, 68, mingles anarchy, virtuosity, deep blues and hammy shtick in ways that keep all eyes on him.... [Guy] loves extremes: sudden drops from loud to soft, or a sweet, sustained guitar solo followed by a jolt of speed, or a high, imploring vocal cut off with a rasp.... Whether he's singing with gentle menace or bending new curves into a blue note, he is a master of tension and release, and his every wayward impulse was riveting.[23]

In an interview taped on April 14, 2000, for the Cleveland college station WRUW-FM, Guy said,

The purpose of me trying to play the kind of rocky stuff is to get airplay...I find myself kind of searching, hoping I'll hit the right notes, say the right things, maybe they'll put me on one of these big stations, what they call 'classic'...if you get Eric Clapton to play a Muddy Waters song, they call it classic, and they will put it on that station, but you'll never hear Muddy Waters.[24]

Accolades

When inducting Guy into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame, Eric Clapton said, "No matter how great the song, or performance, my ear would always find him out. He stood out in the mix, simply by virtue of the originality and vitality of his playing." [25]

Beck recalled the night he and Vaughan performed with Guy at Buddy Guy's Legends club[26] in Chicago: "That was just the most incredible stuff I ever heard in my life. The three of us all jammed and it was so thrilling. That is as close you can come to the heart of the blues."

Former Rolling Stones bassist Bill Wyman said,

Guitar Legends do not come any better than Buddy Guy. He is feted by his peers and loved by his fans for his ability to make the guitar both talk and cry the blues. Such is Buddy's mastery of the guitar that there is virtually no guitarist that he cannot imitate.[27]

Guy was a judge for the 6th and 8th annual Independent Music Awards to support independent artists.[28]

Guy has influenced the styles of subsequent artists such as Reggie Sears[29] and Jesse Marchant of JBM.[30]

On February 21, 2012, Guy performed in concert at the White House for President Barack Obama and First Lady Michelle Obama. During the finale of the concert, he persuaded the President to sing a few bars of "Sweet Home Chicago".[31]

Awards

On September 20, 1996, Guy was inducted into Guitar Center's Hollywood Rockwalk.[32]

Guy has won eight Grammy Awards, for his work on electric and acoustic guitars and for contemporary and traditional forms of blues music, as well as a Lifetime Achievement Award.[33]

In 2003, he was presented with the National Medal of Arts, awarded by the President of the United States to those who have made extraordinary contributions to the creation, growth and support of the arts in the United States.[34]

By 2004, Guy had also earned 23 W.C. Handy Awards, Billboard magazine's Century Award (he was its second recipient) for distinguished artistic achievement, and the title of Greatest Living Electric Blues Guitarist.

Guy was inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame on March 14, 2005, by Eric Clapton and B.B. King. Clapton recalled seeing Guy perform in London's Marquee Club in 1965, impressing him with his technique, his looks and his charismatic showmanship. He remembered seeing Guy pick the guitar with his teeth and play it over his head—two tricks that later influenced Jimi Hendrix.[citation needed] Guy's acceptance speech was concise: "If you don’t think you have the blues, just keep living." He had previously served on the nominating committee of the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame.

In 2008, Guy was inducted into the Louisiana Music Hall of Fame, performing at the Texas Club in Baton Rouge to commemorate the occasion.

In October 2009, he performed "Let Me Love You Baby" with Jeff Beck at the 25th anniversary concert at the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame.[35]

On November 15, 2010, he performed a live set for Guitar Center Sessions on DirecTV. The episode also included an interview with Guy by program host Nic Harcourt.[36]

On December 2, 2012, Guy was awarded the 2012 Kennedy Center Honors.[37] At his induction, Kennedy Center chairman David Rubenstein said, "Buddy Guy is a titan of the blues and has been a tremendous influence on virtually everyone who has picked up an electric guitar in the last half century".[38] He was honored that night along with Dustin Hoffman, Led Zeppelin (John Paul Jones, Jimmy Page and Robert Plant), David Letterman and Natalia Makarova.[39]

On January 28, 2014, Guy was inducted into Musicians Hall of Fame and Museum.[40]

In 2015, Guy received a Grammy Lifetime Achievement Award from the National Academy of Recording Arts and Sciences.[41]

Born to Play Guitar won a Grammy Award in 2016 for Best Blues Album.[42][43] Also in 2016, Guy toured the US east coast as the opening act for Jeff Beck.[44]

December 8, 2018 was designated "Buddy Guy Day" by Louisiana and Mississippi officials and a stretch of Highway 418 through Lettsworth was designated "Buddy Guy Way."[45]

In 2018, Guy was honored with a marker on the Mississippi Blues Trail in Pointe Coupee Parish, Louisiana.[46]

In 2019, Guy received the Golden Plate Award of the American Academy of Achievement presented by Awards Council member Jimmy Page.[47][48]

Personal life

Buddy Guy was born as George Guy to Sam and Isabel Guy in Lettsworth, Louisiana. He was one of five children born to the couple. His brother Phil Guy was also a blues musician.

He married Joan Guy in 1959. They have six children together: Charlotte (1961), Carlise (1963), Colleen (1965), George Jr., Gregory, and Geoffrey.[49] Greg Guy also plays blues guitar.[50]

He was married to Jennifer Guy from 1975 to 2002.[49] They have two children together; Rashawnna and Michael.[49] The marriage ended in divorce. Rashawnna Guy, better known by her stage name Shawnna, is a rapper. Guy currently lives in Orland Park, Illinois, a suburb south of Chicago.[8]

Discography

- I Left My Blues in San Francisco (1967)

- A Man and the Blues (1968)

- Hold That Plane! (1972)

- The Blues Giant / Stone Crazy! (1979)

- Breaking Out (1980)

- DJ Play My Blues (1982)

- Damn Right, I've Got the Blues (1991)

- Feels Like Rain (1993)

- Slippin' In (1994)

- Heavy Love (1998)

- Sweet Tea (2001)

- Blues Singer (2003)

- Bring 'Em In (2005)

- Skin Deep (2008)

- Living Proof (2010)

- Rhythm & Blues (2013)

- Born to Play Guitar (2015)

- The Blues Is Alive and Well (2018)

with Junior Wells

- Hoodoo Man Blues (1965)

- Chicago / The Blues / Today!, Vol. 1 (1966)

- It's My Life, Baby! (1966)

- Coming at You (1968)

- Buddy and the Juniors (1970, also with Junior Mance)

- Southside Blues Jam (1970)

- Play the Blues (1972)

- Pleading the Blues (1979)

- Going Back (1981)

- Better Off with the Blues (1993)

with Phil Guy

- Buddy & Phil (1981)

- The Red Hot Blues of Phil Guy (1982)

- Bad Luck Boy (1983)

- All Star Chicago Blues Session (1994)

- He's My Blues Brother (2006)

with Memphis Slim

- Southside Reunion (1971)

See also

References

- ^ a b c d "Buddy Guy Biography". Biography.com. A&E Television Networks. Archived from the original on 15 May 2015. Retrieved 15 May 2015.

- ^ "Buddy Guy". Rock and Roll Hall of Fame.

- ^ "The 100 Greatest Guitarists of All Time". Rolling Stone. 2015-12-18. Retrieved 2018-10-26.

- ^ "The 100 Greatest Guitar Songs of All Time". Archived from the original on May 31, 2008. Retrieved 2008-05-31.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link). Rolling Stone. Retrieved 2011-01-25. "Cut in 1961 for Chess, the full seven minutes of this blinding blues went unreleased for nearly a decade. Guy solos with a steel-needle tone, answering his own barking vocal with dizzying pinpoint stabs. 'I don't know how to bend the string', he told RS. 'Let me break it.’" - ^ "Buddy Guy". Rolling Stone archive Archived 2018-05-03 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved June 29, 2015.

- ^ Guy, Buddy; Wilcock, Donald (1999). Damn Right I've Got the Blues. Duane Press. p. 152. ISBN 094262713X.

- ^ Guy, Buddy; Ritz, David. (2012) When I Left Home: My Story. Cambridge: Da Capo Press. ISBN 978-0-306-81957-5

- ^ a b c d David Remnick, "Buddy Guy Is Keeping the Blues Alive," The New Yorker, March 11, 2019.

- ^ Tomko, Gene (2020). Encyclopedia of Louisiana Musicians: Jazz, Blues, Cajun, Creole, Zydeco, Swamp Pop, and Gospel. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press. p. 120. ISBN 9780807169322.

- ^ Fancourt, Les; McGrath, Bob (2019). The Blues Discography: 1943–1970, Third Edition. Canada: Eyeball Productions. p. 233. ISBN 978-1-9995488-0-3.

- ^ Dahl, Bill (August 27, 1993). "Ike Turner Upbeat About His Future". Chicago Tribune.

- ^ Corp, Hal Leonard (2014-07-01). 25 Top Blues Songs – Tab. Tone. Technique.: Tab+. Hal Leonard Corporation. ISBN 9781495001017.

- ^ Collis, John (1998). The Story of Chess Records. Bloomsbury Publishing USA. p. 158. ISBN 9781582340050.

Sit and Cry (the Blues) buddy guy.

- ^ Prato, Greg (April 25, 2012). "Buddy Guy Sets the Record Straight With New Book". Rolling Stone.

- ^ "We've Got The Westside Covered". Riverside Reader. Retrieved 2012-12-25.

- ^ Murray, Charles Shaar (2013). Boogie Man: The Adventures of John Lee Hooker in the American Twentieth Century. St. Martin's Press. p. 303. ISBN 9781466852365.

- ^ a b Bowling, David; Clapton, Eric (2013). Eric Clapton FAQ: All That's Left to Know About Slowhand. Hal Leonard Corporation. ISBN 9781617135743.

- ^ Donald Liebenson (29 March 2009), Buddy Guy is play-acting, not playing, in 'Electric Mist', Chicago Tribune, accessed 17 November 2019

- ^ Everett, Matthew (27 February 2013). "Buddy Guy Keeps the Blues Alive". MetroPulse. Scripps Interactive Newspapers Group. Archived from the original on 27 March 2013. Retrieved 26 March 2013.

- ^ "Buddy Guy's $5 Million Home". Ebony: 156–162. September 2000. ISSN 0012-9011.

- ^ Sugrue, Dan (2016). "Waiting for Buddy Guy: Chicago Blues at the Crossroads". WGN radio, March 8, 2016.

- ^ Rosen, Jody (June 25, 2019). "Here Are Hundreds More Artists Whose Tapes Were Destroyed in the UMG Fire". The New York Times. Retrieved June 28, 2019.

- ^ Pareles, Jon (January 31, 2005). "A Guitarist Pulls the Audience's Strings". NY Times. Retrieved October 14, 2020.

- ^ "Buddy Guy". WBSS Media. Retrieved October 14, 2020.

- ^ "BB King and Eric Clapton induct Buddy Guy Rock and Roll Hall of Fame Inductions 2005". YouTube.com. Rock and Roll Hall of Fame + Museum. 8 December 2010. Retrieved 15 May 2015.

- ^ "Buddy Guy's Legends". Buddyguys.com. 2011-11-26. Archived from the original on 2011-07-08. Retrieved 2011-12-30.

- ^ Marshall, Matt (2011-06-30). "Happy Birthday Buddy Guy". Retrieved 2018-06-29.

- ^ "Independent Music Awards". Independent Music Awards. Archived from the original on 2011-07-13. Retrieved 2012-12-25.

- ^ Duncan, Andrew (July 9, 2010). "JBM – Reflections". Zaptown. Archived from the original on September 17, 2011. Retrieved 2011-05-23.

- ^ Compton, Matt (2012-02-21). "President Obama Sings "Sweet Home Chicago"". WhiteHouse.gov. US Government. Retrieved 2012-05-21.

- ^ Guitar Center's Hollywood Rockwalk Retrieved October 7, 2013.

- ^ "Buddy Guy," Grammy.com, retrieved April 16, 2019.

- ^ "Lifetime Honors: National Medal of Arts". Nea.gov. Archived from the original on 2010-01-20. Retrieved 2012-12-25.

- ^ "The 25th Anniversary Rock & Roll Hall Of Fame Concerts (4CD)". Retrieved 2011-11-25.

- ^ Guitar Center Sessions with host Nic Harcourt Retrieved July 1, 2013.

- ^ "Kennedy Center Honors Buddy Guy & Led Zeppelin". Americanbluesscene.com. 2012-12-03. Archived from the original on 2013-01-01. Retrieved 2012-12-25.

- ^ "Dustin Hoffman, David Letterman, Natalia Makarova, Buddy Guy, Led Zeppelin Are Kennedy Center Honorees". Playbill.com. 2012-09-12. Archived from the original on 2012-11-09. Retrieved 2012-12-25.

- ^ Gans, Andrew. "Dustin Hoffman, David Letterman, Natalia Makarova, Buddy Guy, Led Zeppelin Are Kennedy Center Honorees" Archived 2012-11-09 at the Wayback Machine playbill.com, September 12, 2012

- ^ "Buddy Guy Accepts His Musicians Hall of Fame Award". MusiciansHallofFame.com. Archived from the original on 8 May 2015. Retrieved 15 May 2015.

- ^ "Sam Smith wins 4 Grammys, Beck takes home album of the year," Chicago Tribune, February 9, 2015.

- ^ "Grammy Nominations 2016: See the Full List of Nominees". Billboard. December 7, 2015. Retrieved December 7, 2015.

- ^ "The GRAMMYs on Twitter: "Congrats Best Blues Album @TheRealBuddyGuy – 'Born To Play Guitar' #GRAMMYs "". 2016-02-15. Retrieved 2016-08-28 – via Twitter.

- ^ BEN RATLIFF (July 21, 2016). "Review: Jeff Beck's Virtuosic Sleight of Hand at Madison Square Garden". New York Times.

- ^ "Buddy Guy to be honored in Louisiana hometown with historic marker, highway designation," The Advocate, December 3, 2018.

- ^ Advocate, JOHN WIRT | Special to the. "Blues legend Buddy Guy on new trail marker in Pointe Coupee: 'Coming home is the best'". The Advocate. Retrieved 2020-02-10.

- ^ "Golden Plate Awardees of the American Academy of Achievement". www.achievement.org. American Academy of Achievement.

- ^ "2019 Summit Overview".

- ^ a b c Guy, Buddy &, Ritz, David (2012). When I Left Home: My Story. Da Capo Press. p. 320. ISBN 978-0306821790.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Shafel Omiccioli, Kristin (10 September 2014). "Buddy Guy is still the baddest". KCMetropolis.org. Retrieved 15 May 2015.

Further reading

- Wilcox, Donald; Guy, Buddy (1993). Damn Right I've Got the Blues: Buddy Guy and the Blues Roots of Rock-And-Roll (1999 paperback ed.). Duane Press. ISBN 0-942627-13-X.

External links

- Official website[permanent dead link]

- Buddy Guy at the Encyclopædia Britannica

- Buddy Guy discography at Discogs

- Buddy Guy at AllMusic

- Template:Curlie

- Buddy Guy at IMDb

- Harcourt, Nic. "Buddy Guy at Guitar Center".

- 1936 births

- Living people

- American blues guitarists

- American male guitarists

- American blues singers

- American memoirists

- Atlantic Records artists

- Charly Records artists

- Chess Records artists

- Chicago blues musicians

- Contemporary blues musicians

- Delmark Records artists

- Electric blues musicians

- Grammy Lifetime Achievement Award winners

- Jive Records artists

- Kennedy Center honorees

- Lead guitarists

- MCA Records artists

- MPS Records artists

- People from Pointe Coupee Parish, Louisiana

- McKinley Senior High School alumni

- Musicians from Baton Rouge, Louisiana

- Blues musicians from Louisiana

- Blue Thumb Records artists

- RCA Records artists

- Songwriters from Louisiana

- United States National Medal of Arts recipients

- Vanguard Records artists

- Zomba Group of Companies artists

- African-American guitarists

- Songwriters from Illinois

- Singers from Louisiana

- Guitarists from Chicago

- Guitarists from Louisiana

- 20th-century American guitarists

- Black & Blue Records artists

- Mississippi Blues Trail