Louis Riel

Louis Riel | |

|---|---|

| |

| President - Provisional Government, then, Legislative Assembly of Assiniboia | |

| In office 27 December 1869 – 24 June 1870 | |

| Succeeded by | Alfred Boyd, 1st Manitoba Premier |

| Member of Parliament for Provencher | |

| In office 13 October 1873 – 22 January 1874 | |

| Preceded by | George-Étienne Cartier, MP |

| Succeeded by | Andrew Bannatyne, MP |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 22 October 1844 St. Boniface, Red River Colony, Rupert's Land, British North America |

| Died | 16 November 1885 (aged 41) Regina, Northwest Territories, Canada |

| Spouse | Marguerite Monet dite Bellehumeur (m. 1881) |

| Children |

|

| Signature |  |

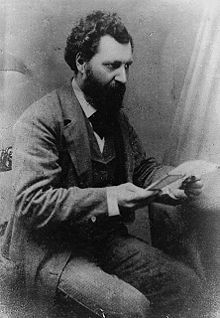

Louis "David" Riel (/ˈluːi riˈɛl/; French: [lwi ʁjɛl]; 22 October 1844 – 16 November 1885) was a Canadian politician, a founder of the province of Manitoba, and a political leader of the Métis people in pre-Manitoba Northwest Territories.[1][2][3] He led two resistant movements against the government of Canada led by its first post-Confederation prime minister, John A. Macdonald. Riel sought to defend Métis rights and identity as the Northwest came progressively under the Canadian sphere of influence. Over the past seven decades[when?] especially, he has been viewed as a folk hero and protector of minority rights and culture by Métis, French Canadian and other Canadian minorities. Arguably, Riel has received more formal organizational and academic scrutiny than any other figure in Canadian history.[4]

The first resistance movement led by Riel is now known as the Red River Resistance of 1869–1870.[5] The provisional government established by Riel ultimately negotiated the terms under which the new province of Manitoba entered the Canadian Confederation.[6] Riel ordered the execution of Thomas Scott, and fled to the United States to escape prosecution. He was elected three times as member of the House of Commons, but, fearing for his life, he could never take his seat. During these years in exile he came to believe that he was a divinely chosen leader and prophet, a belief which would later resurface and influence him when he agreed to lead the Saskatchewan Métis in 1884. Because of this new religious conviction, Catholic leaders who had supported him before increasingly repudiated him. He married in 1881 while in exile in the Montana Territory in the United States; he fathered three children.

In 1884 Riel was called upon by the Métis leaders in Saskatchewan to help resolve longstanding rights grievances with the Canadian government, which led to armed conflict with government forces, the North-West Rebellion of 1885. Ottawa used the new rail lines to send in thousands of combat soldiers. Defeated at the Battle of Batoche, Riel turned himself to General Middleton scouts and was imprisoned in Regina where he was convicted at trial of high treason. Despite protests, popular appeals and the jury's call for clemency, Prime Minister Macdonald did not intervene and Riel was executed by hanging. Riel was seen as a heroic victim by French Canadians; his execution had a lasting negative impact on Canada, polarizing the new nation along ethno-religious lines. Although only a few hundred Métis were affected by the Rebellion in Saskatchewan, the long-term result was that the Métis were marginalized in the Prairie Provinces by the increasingly English-dominated majority. An even more important long-term impact was the bitter alienation Francophones across Canada felt, and anger against the repression by their countrymen.[7]

Riel's historical reputation has long been polarized between portrayals as a dangerous religious fanatic and rebel opposed to the Canadian nation, and, by contrast, as a charismatic leader intent on defending his Métis people from the unfair encroachments by the federal government eager to give Orangemen-dominated Ontario settlers priority access to North-West land. Riel is increasingly celebrated as a proponent of Canadian multiculturalism, though this tends to be at odds with his political beliefs grounded on Métis nationalism and political independence.[8]

Early life

Red River Settlement was a Rupert's Land territory administered by the Hudson's Bay Company (HBC) that was at mid-19th-century largely inhabited by Métis people of mixed Aboriginal-European descent whose ancestors were for the most part Scottish and English men married to Cree women and French-Canadian men married to Saulteaux/Ojibwa women.[9] Louis Riel was born in Red River in 1844 in his grandparents' small one room home, the Lagimodière-Gaboury home, a house in north St. Boniface at the fork of the Red and Seine rivers across the Red River from the Point Douglas neighbourhood, St. Boniface and Point Douglas both being part of present-day Winnipeg city in Manitoba.[10]

Riel was the eldest of eleven children in a locally well-respected family.[11] His father, who was of Franco-Chipewyan Métis descent, had gained prominence in this community by organizing a group that supported Guillaume Sayer, a Métis arrested and tried for challenging the HBC's historical trade monopoly.[12]

Sayer's eventual release due to agitations by Louis Sr.'s group effectively ended the monopoly, and the name Riel was therefore well known in the Red River area. His mother was the daughter of Jean-Baptiste Lagimodière and Marie-Anne Gaboury, one of the earliest European descended families to settle in the Red River Settlement in 1812. The Riels were noted for their devout Catholicism and strong family ties.[13] When he was seven he began school in the bishop’s library.[14] At age ten Riel was educated in St. Boniface Catholic schools including eventually a school run by the French Christian Brothers.[15] At age thirteen he came to the attention of Bishop Alexandre Taché who was eagerly promoting the priesthood for talented young Métis. In 1858 Taché arranged for Riel to attend the Petit Séminaire of the Collège de Montréal, under the direction of the Sulpician order.[12] Descriptions of him at the time indicate that he was a fine scholar of languages, science, and philosophy.[16]

Following news of his father's premature death in 1864, Riel lost interest in the priesthood and withdrew from the college in March 1865. For a time, he continued his studies as a day student in the convent of the Grey Nuns, but was soon asked to leave, following breaches of discipline. He remained in Montreal for over a year, living at the home of his aunt, Lucie Riel. Impoverished by the death of his father, Riel took employment as a law clerk in the Montreal office of Rodolphe Laflamme.[8] During this time he was involved in a failed romance with a young woman named Marie–Julie Guernon.[17] This progressed to the point of Riel having signed a contract of marriage, but his fiancée's family opposed her involvement with a Métis, and the engagement was soon broken. Compounding this disappointment, Riel found legal work unpleasant and, by early 1866, he had resolved to leave Canada East.[18] Some of his friends said later that he worked odd jobs in Chicago, Illinois, while staying with poet Louis-Honoré Fréchette, and wrote poems himself in the manner of Lamartine, and that he was briefly employed as a clerk in Saint Paul, Minnesota, before returning to the Red River settlement on 26 July 1868.[19]

Red River Resistance

The majority population of the Red River had historically been Métis and First Nation people. Upon his return, Riel found that religious, nationalistic, and racial tensions were exacerbated by an influx of Anglophone Protestant settlers from Ontario. The political situation was also uncertain, as ongoing negotiations for the transfer of Rupert's Land from the Hudson's Bay Company to Canada had not addressed the political terms of transfer. Finally, despite warnings to the Macdonald government from Bishop Taché[20] and the HBC governor William Mactavish that any such activity would precipitate unrest, the Canadian minister of public works, William McDougall, ordered a survey of the area. The arrival on 20 August 1869 of a survey party headed by Colonel John Stoughton Dennis increased anxiety among the Métis as the survey was being carried out as a grid system of townships (each township consisting of 36 equal-sized sections, that is, in squares similar to existing Ontario land surveys) that, unwisely, cut across existing Métis' Red River Settlement river lots.[21][22][23]

Riel emerges as a leader

In late August, Riel denounced the survey in a speech, and on 11 October 1869, the survey's work was disrupted by a group of Métis that included Riel. This group organized itself as the "Métis National Committee" on 16 October, with Riel as secretary and John Bruce as president.[24] When summoned by the HBC-controlled Council of Assiniboia to explain his actions, Riel declared that any attempt by Canada to assume authority would be contested unless Ottawa had first negotiated terms with the Métis. Nevertheless, the non-bilingual McDougall was appointed the lieutenant governor-designate, and attempted to enter the settlement on 2 November. McDougall's party was turned back near the Canada–US border, and on the same day, Métis led by Riel seized Fort Garry.[25][26]

On 6 November, Riel invited Anglophones to attend a convention alongside Métis representatives to discuss a course of action, and on 1 December he proposed to this convention a list of rights to be demanded as a condition of union. Much of the settlement came to accept the Métis point of view, but a passionately pro-Canadian minority began organizing in opposition. Loosely constituted as the Canadian Party, this group was led by John Christian Schultz,[27] Charles Mair,[28] Colonel John Stoughton Dennis,[29] and a more reticent Major Charles Boulton.[30] McDougall attempted to assert his authority by authorizing Dennis to raise a contingent of armed men, but the Anglophone settlers largely ignored this call to arms. Schultz, however, attracted approximately fifty recruits and fortified his house and store. Riel ordered Schultz's home surrounded, and the outnumbered Canadians soon surrendered and were imprisoned in Upper Fort Garry.

Provisional government

Hearing of the unrest, Ottawa sent three emissaries to the Red River, including HBC representative Donald Alexander Smith.[31] While they were en route, the Métis National Committee declared a provisional government on 8 December, with Riel becoming its president on 27 December.[32] Meetings between Riel and the Ottawa delegation took place on 5 and 6 January 1870, but when these proved fruitless, Smith chose to present his case in a public forum. Smith assured large audiences of the Government's goodwill in meetings on 19 and 20 January, leading Riel to propose the formation of a new convention split evenly between Francophone and Anglophone settlers to consider Smith's instructions. On 7 February, a new list of rights was presented to the Ottawa delegation, and Smith and Riel agreed to send representatives to Ottawa to engage in direct negotiations on that basis.[2] The provisional government[33] established by Louis Riel published its own newspaper titled New Nation and established the Legislative Assembly of Assiniboia to pass laws.[34] The Legislative Assembly of Assiniboia was the first elected government at the Red River Settlement and functioned from 9 March to 24 June 1870. The assembly had 28 elected representatives, including a president, Louis Riel, an executive council (government cabinet), adjutant general (chief of military staff), chief justice and clerk.[35]

The execution of Thomas Scott

Despite the apparent progress on the political front, the Canadian party continued to plot against the provisional government. However, they suffered a setback on 17 February, when forty-eight men, including Boulton and Thomas Scott, were arrested near Fort Garry.

Boulton was tried by a tribunal headed by Ambroise-Dydime Lépine and sentenced to death for his interference with the provisional government.[36] He was pardoned, but Scott interpreted this as weakness by the Métis, who he regarded with open contempt. After Scott repeatedly quarreled with his guards, they insisted that he be tried for insubordination. At his court martial he was found guilty and was sentenced to death. Riel was repeatedly entreated to commute the sentence, but Riel responded, "I have done three good things since I have commenced: I have spared Boulton's life at your instance, I pardoned Gaddy, and now I shall shoot Scott."[37]

Scott was executed by firing squad on 4 March. Riel's motivations have been the cause of much speculation, but his own justification was that he felt it necessary to demonstrate to the Canadians that the Métis must be taken seriously. Protestant Canada did take notice, swore revenge, and set up a "Canada First" movement to mobilize their anger.[38][39]

Creation of Manitoba and the Wolseley expedition

The delegates representing the provisional government departed for Ottawa in March. Although they initially met with legal difficulties arising from the execution of Scott, they soon entered into direct talks with Macdonald and George-Étienne Cartier.[40] An agreement enshrining the demands in the list of rights was quickly reached, and this formed the basis for the Manitoba Act[41] of 12 May 1870, which formally admitted Manitoba into the Canadian confederation. However, the negotiators could not secure a general amnesty for the provisional government.

As a means of exercising Canadian authority in the settlement and dissuading American expansionists, a Canadian military expedition under Colonel Garnet Wolseley was dispatched to the Red River.[42] Although the government described it as an "errand of peace", Riel learned that Canadian militia elements in the expedition meant to lynch him, and he fled as the expedition approached the Red River. The arrival of the expedition on 20 August marked the effective end of the Red River Rebellion.

Intervening years

Amnesty question

It was not until 2 September 1870 that the new lieutenant-governor Adams George Archibald arrived and set about the establishment of civil government.[43] Without an amnesty, and with the Canadian militia beating and intimidating his sympathizers, Riel fled to the safety of the St. Joseph's mission across the Canada–US border in the Dakota Territory. However the results of the first provincial election in December 1870 were promising for Riel, as many of his supporters came to power. Nevertheless, stress and financial troubles precipitated a serious illness—perhaps a harbinger of his future mental afflictions—that prevented his return to Manitoba until May 1871.

The settlement now faced a possible threat, from cross-border Fenian raids coordinated by his former associate William Bernard O'Donoghue.[44] Archibald proclaimed a general call to arms on 4 October. Companies of armed horsemen were raised, including one led by Riel. When Archibald reviewed the troops in St. Boniface, he made the significant gesture of publicly shaking Riel's hand, signaling that a rapprochement had been affected. This was not to be—when this news reached Ontario, Mair and members of the Canada First movement whipped up anti-Riel (and anti-Archibald) sentiment. With Federal elections coming in 1872, Macdonald could ill afford further rift in Quebec–Ontario relations and so he did not offer an amnesty. Instead he quietly arranged for Taché to offer Riel a bribe of $1,000 to remain in voluntary exile. This was supplemented by an additional £600 from Smith for the care of Riel's family.[45]

Nevertheless, by late June Riel was back in Manitoba and was soon persuaded to run as a member of parliament for the electoral district of Provencher. However, following the early September defeat of George-Étienne Cartier in his home riding in Quebec, Riel stood aside so that Cartier—on record as being in favour of amnesty for Riel—might secure a seat in Provencher. Cartier won by acclamation, but Riel's hopes for a swift resolution to the amnesty question were dashed following Cartier's death on 20 May 1873. In the ensuing by-election in October 1873, Riel ran unopposed as an Independent, although he had again fled, a warrant having been issued for his arrest in September. Lépine was not so lucky; he was captured and faced trial.

Riel made his way to Montreal and, fearing arrest or assassination, vacillated as to whether he should attempt to take up his seat in the House of Commons—Edward Blake, the Premier of Ontario, had announced a bounty of $5,000 for his arrest.[46] Famously, Riel was the only Member of Parliament who was not present for the great Pacific Scandal debate of 1873 that led to the resignation of the Macdonald government in November. Liberal leader Alexander Mackenzie became the interim prime minister, and a general election was held in January 1874. Although the Liberals under Mackenzie formed the new government, Riel easily retained his seat. Formally, Riel had to sign a register book at least once upon being elected, and he did so under disguise in late January. He was nevertheless stricken from the rolls following a motion supported by Schultz, who had become the member for the electoral district of Lisgar.[47] Undeterred, Riel prevailed again in the resulting by-election, and although again expelled, his symbolic point had been made and public opinion in Quebec was strongly tipped in his favour.

Exile and mental illness

During this period, Riel had been staying with the Oblate fathers in Plattsburgh, New York, who introduced him to parish priest Fabien Martin dit Barnabé in the nearby village of Keeseville.[2] It was here that he received news of Lépine's fate: following his trial for the murder of Scott, which had begun on 13 October 1874, Lépine was found guilty and sentenced to death. This sparked outrage in the sympathetic Quebec press, and calls for amnesty for both Lépine and Riel were renewed. This presented a severe political difficulty for Mackenzie, who was hopelessly caught between the demands of Quebec and Ontario. However, a solution was forthcoming when, acting on his own initiative, the Governor General Lord Dufferin commuted Lépine's sentence in January 1875. This opened the door for Mackenzie to secure from parliament an amnesty for Riel, on the condition that he remain in exile for five years.[8]

During his time of exile, he was primarily concerned with religious rather than political matters. Much of these emerging religious beliefs were based on a supportive letter dated 14 July 1875 that he received from Montreal's Bishop Ignace Bourget.[2] However, defence lawyers at his treason trial failed in their efforts to find evidence showing Riel to be "a psychologically troubled megalomaniac".[48][49] His mental state deteriorated, and following a violent outburst he was taken to Montreal, where he was under the care of his uncle, John Lee, for a few months. But after Riel disrupted a religious service, Lee arranged to have him committed in an asylum in Longue-Pointe on 6 March 1876 under the assumed name "Louis R. David".[8] Fearing discovery, his doctors soon transferred him to the Beauport Asylum near Quebec City under the name "Louis Larochelle".[50] While he suffered from sporadic irrational outbursts, he continued his religious writing, composing theological tracts with an admixture of Christian and Judaic ideas. He consequently began calling himself Louis "David" Riel, prophet of the new world, and he would pray (standing) for hours, having servants help him to hold his arms in the shape of a cross.

Nevertheless, he slowly recovered, and was released from the asylum on 23 January 1878[51] with an admonition to lead a quiet life. He returned for a time to Keeseville, where he became involved in a passionate romance with Evelina Martin dite Barnabé,[2] sister of his friend, Father Fabien Barnabé. But with insufficient means to propose marriage, Riel returned to the west, hoping that she might follow. However, their correspondence ended abruptly, Evelina being surprised to learn in a newspaper of the marriage of Louis and Marguerite Monet.[52]

Montana and family life

In the fall of 1878, Riel returned to St. Paul, and briefly visited his friends and family. This was a time of rapid change for the Métis of the Red River—the buffalo on which they depended were becoming increasingly scarce, the influx of settlers was ever-increasing, and much land was sold to unscrupulous land speculators. Like other Red River Métis who had left Manitoba, Riel headed further west to start a new life.

Travelling to the Montana Territory, he became a trader and interpreter in the area surrounding Fort Benton. Observing rampant alcoholism and its detrimental impact on the Native American and Métis people, he engaged in an unsuccessful attempt to curtail the whisky trade. In Pointe-au-Loup, Fort Berthold, Dakota Territory in 1881,[53][54] he married the young Métis Marguerite Monet dite Bellehumeur (1861–1886),[55] according to the custom of the country {à la façon du pays), on 28 April, the marriage being solemnized before Father Damiani on 9 March 1882 at Carroll, Montana.[56] They were to have three children: Jean-Louis (1882–1908); Marie-Angélique (1883–1897); and a boy who was born and died on 21 October 1885, less than one month before Riel was hanged.[2]

Riel soon became involved in the politics of Montana, and in 1882, actively campaigned on behalf of the Republican Party. He brought a suit against a Democrat for rigging a vote, but was then himself accused of fraudulently inducing British subjects to take part in the election. In response, Riel applied for United States citizenship and was naturalized on 16 March 1883.[57] With two young children, he had by 1884 settled down and was teaching school at the St. Peter's Jesuit mission in the Sun River district of Montana.

The North-West Rebellion

Grievances in the Saskatchewan territory

Following the Red River Rebellion, Métis travelled west and settled in the Saskatchewan Valley, especially along the south branch of the river in the country surrounding the Saint-Laurent mission (near modern St. Laurent de Grandin, Saskatchewan). But by the 1880s, it had become clear that westward migration was no panacea for the troubles of the Métis and the plains Indians. The rapid collapse of the buffalo herd was causing near starvation among the Plains Cree and Blackfoot First Nations. This was exacerbated by a reduction in government assistance in 1883, and by a general failure of Ottawa to live up to its treaty obligations.

The Métis were likewise obliged to give up the hunt and take up agriculture—but this transition was accompanied by complex issues surrounding land claims similar to those that had previously arisen in Manitoba. Moreover, settlers from Europe and the eastern provinces were also moving into the Saskatchewan territories, and they too had complaints related to the administration of the territories. Virtually all parties therefore had grievances, and by 1884 Anglophone settlers, Anglo-Métis and Métis communities were holding meetings and petitioning a largely unresponsive government for redress.

In the electoral district of Lorne, a meeting of the south branch Métis was held in the village of Batoche on 24 March, and thirty representatives voted to ask Riel to return and represent their cause. On 6 May a joint "Settler's Union" meeting was attended by both the Métis and English-speaking representatives from Prince Albert, including William Henry Jackson, an Ontario settler sympathetic to the Métis and known to them as Honoré Jackson, and James Isbister of the Anglo-Métis.[58] It was here resolved to send a delegation to ask Riel's assistance in presenting their grievances to the Canadian government.

Return of Riel

The head of the delegation to Riel was Gabriel Dumont,[59] a respected buffalo hunter and leader of the Saint-Laurent Métis who had known Riel in Manitoba. James Isbister[60] was the lone Anglo-Métis delegate. Riel was easily swayed to support their cause—which was perhaps not surprising in view of Riel's continuing conviction that he was the divinely selected leader of the Métis and the prophet of a new form of Christianity. Riel also intended to use the new position of influence to pursue his own land claims in Manitoba. The party departed 4 June, and arrived back at Batoche on 5 July.

Upon his arrival Métis and Anglophone settlers alike formed an initially favourable impression of Riel following a series of speeches in which he advocated moderation and a reasoned approach. During June 1884, the Plains Cree leaders Big Bear[61] and Poundmaker[62] were independently formulating their complaints, and subsequently held meetings with Riel. However, the Native grievances were quite different from those of the settlers, and nothing was then resolved. Inspired by Riel,[63] Honoré Jackson and representatives of other communities set about drafting a petition,[64] and Jackson on 28 July released a manifesto detailing grievances and the settler's objectives. A joint Anglo-Métis central committee with Jackson acting as secretary worked to reconcile proposals from different communities. In the interim, Riel's support began to waver.

As Riel's religious pronouncements became increasingly heretical the clergy distanced themselves, and father Alexis André cautioned Riel against mixing religion and politics. Also, in response to bribes by territorial lieutenant-governor and Indian commissioner Edgar Dewdney,[65] local English-language newspapers adopted an editorial stance critical of Riel.[2] Nevertheless, the work continued, and on 16 December Riel forwarded the committee's petition to the government, along with the suggestion that delegates be sent to Ottawa to engage in direct negotiation. Receipt of the petition was acknowledged by Joseph-Adolphe Chapleau, Macdonald's Secretary of State, although Macdonald himself would later deny having ever seen it.[2] By then many original followers had left; only 250 remained at Batoche when it fell in May 1885.[66]

Break with the church

Historian Donald Creighton has argued that Riel had become a changed man:

In the 15 years since he had left Red River, his megalomania had grown greater than ever. His ungovernable rages, delusions of grandeur, messianic claims, and dictatorial impulses had all become more extreme; but these violent excesses were not the only symptoms of his curious mental and moral decline. He had lost his shrewd appreciation of realities. His sense of direction was confused in his purposes were equivocal. He showed, at intervals, a cynical selfishness and the ruthless cupidity. ... although in public he professed that his sole aim was the redress of the Métis grievances, and private he was quite ready to promise that if the government made him a satisfactory personal payment of a few thousand dollars he would induce his credulous followers to accept almost any settlement the federal authorities desired, and would quietly leave Canada forever.[67]

While Riel awaited news from Ottawa he considered returning to Montana, but had by February resolved to stay. Without a productive course of action, Riel began to engage in obsessive prayer, and was experiencing a significant relapse of his mental agitations. This led to a deterioration in his relationship with the Catholic clergy, as he publicly espoused an increasingly heretical doctrine. On 11 February 1885, a response to the petition was received. The government proposed to take a census of the North-West Territories, and to form a commission to investigate grievances. This angered a faction of the Métis who saw it as a mere delaying tactic; they favoured taking up arms at once.

Riel became the leader of this faction, but he lost the support of almost all Anglophones and Anglo-Métis, the Catholic Church, and the great majority of Indians. He also lost the support of the Métis faction supporting local leader Charles Nolin.[68] But Riel, undoubtedly influenced by his messianic delusions,[69] became increasingly supportive of this course of action. In the church at Saint-Laurent on 15 March, Riel disrupted a sermon to argue for this position, following which he was barred from receiving the sacraments. He took more and more about his "divine revelations". But disenchanted with the status quo, and swayed by Riel's charisma and eloquent rhetoric, hundreds of Métis remained loyal to Riel, despite his proclamations that Bishop Ignace Bourget[50] should be accepted as pope, and that "Rome has fallen".

At his trial, Riel denied allegations that his religious beliefs were as irrational as was being (and continue to be) alleged. He explained as follows:

I wish to leave Rome aside, inasmuch as it is the cause of division between Catholics and Protestants. I did not wish to force my views ... If I could have any influence in the new world it would be to help in that way, even if it takes 200 years to become practical ... so my children's children can shake hands with the Protestants of the new world in a friendly manner. I do not wish those evils which exist in Europe to be continued, as much as I can influence it, among the (Metis). I do not wish that to be repeated in America.[70]

Open rebellion

On 18 March it became known that the North-West Mounted Police garrison at Battleford was being reinforced. Although only 100 men had been sent in response to warnings from father Alexis André and NWMP superintendent L.N.F. Crozier, a rumour soon began to circulate that 500 heavily armed troops were advancing on the territory. Métis patience was exhausted, and Riel's followers seized arms, took hostages, and cut the telegraph lines between Batoche and Battleford. The Provisional Government of Saskatchewan was declared at Batoche on 19 March, with Riel[71] as the political and spiritual leader and with Dumont assuming responsibility for military affairs.

Riel formed a council called the Exovedate[72] (a neologism meaning "those who have left the flock"), and sent representatives to court Poundmaker and Big Bear. On 21 March, Riel's emissaries demanded that Crozier surrender Fort Carlton, but this was refused. The situation was becoming critical, and on 23 March Dewdney sent a telegraph to Macdonald indicating that military intervention might be necessary. Scouting near Duck Lake on 26 March, a force led by Gabriel Dumont unexpectedly chanced upon a party from Fort Carlton. In the ensuing Battle of Duck Lake, the police were routed, and the Natives also rose up once the news became known. The die was cast for a violent outcome, and the North-West Rebellion was begun in earnest.

Riel had counted on the Canadian government being unable to effectively respond to another uprising in the distant North-West Territories, thereby forcing them to accept political negotiation. This was essentially the same strategy that had worked to such great effect during the 1870 rebellion. In that instance, the first troops did not arrive until three months after Riel seized control. However, Riel had completely overlooked the significance of the Canadian Pacific Railway.[citation needed] Despite some uncompleted gaps, the first Canadian regular and militia units, under the command of Major-General Frederick Dobson Middleton, arrived in Duck Lake less than two weeks after Riel had made his demands.

Knowing that he could not defeat the Canadians in direct confrontation, Dumont had hoped to force the Canadians to negotiate by engaging in a long-drawn out campaign of guerrilla warfare; Dumont realized a modest success along these lines at the Battle of Fish Creek on 24 April 1885.[73] Riel, however, insisted on concentrating forces at Batoche to defend his "city of God". The outcome of the ensuing Battle of Batoche which took place from 9 to 12 May[74] was never in doubt, and on 15 May a disheveled Riel surrendered to Canadian forces. Although Big Bear's forces managed to hold out until the Battle of Loon Lake on 3 June,[75] the rebellion was a dismal failure for Métis and Natives alike, as they surrendered or fled.

Trial for treason

Several individuals closely tied to the government requested that the trial be held in Winnipeg in July 1885. Some historians contend that the trial was moved to Regina because of concerns with the possibility of an ethnically mixed and sympathetic jury.[76] Tom Flanagan states that an amendment of the North-West Territories Act (which dropped the provision that trials with crimes punishable by death should be tried in Manitoba) meant that the trial could be convened within the North-West Territories and did not have to be held in Winnipeg.

Prime Minister Sir John A. Macdonald ordered the trial to be convened in Regina, where Riel was tried before a jury of six Anglophone Protestants, all from the area surrounding the city. The trial began on 20 July 1885, Riel being sentenced to hang on 1 August 1885.[77] Riel delivered two long speeches during his trial, defending his own actions and affirming the rights of the Métis people. He rejected his lawyers' attempt to argue that he was not guilty by reason of insanity, asserting,

Life, without the dignity of an intelligent being, is not worth having.[70]

The jury found him guilty but recommended mercy; nonetheless, Judge Hugh Richardson sentenced him to death, with the date of his execution initially set for 18 September 1885.[48] "We tried Riel for treason," one juror later said, "And he was hanged for the murder of Scott."[78]

Execution

Boulton writes in his memoirs that, as the date of his execution approached, Riel regretted his opposition to the defence of insanity and vainly attempted to provide evidence that he was not sane.[79][80] Requests for a retrial and an appeal to the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council in Britain were denied.[79] Sir John A. Macdonald, who was instrumental in upholding Riel's sentence, is famously quoted as saying:

He shall die [sic] though every dog in Quebec bark in his favour.[81]

Before his execution, Riel was reconciled with the Catholic Church, and assigned Father André as his spiritual advisor. He was also given writing materials so that he could employ his time in prison to write a book. Louis Riel was hanged for treason on 16 November 1885 at the North-West Mounted Police barracks in Regina.[82]

Boulton writes of Riel's final moments,

... Père André, after explaining to Riel that the end was at hand, asked him if he was at peace with men. Riel answered "Yes." The next question was, "Do you forgive all your enemies?" "Yes." Riel then asked him if he might speak. Father André advised him not to do so. He then received the kiss of peace from both the priests, and Father André exclaimed in French, "Alors, allez au ciel!" meaning "So, go to heaven!"[83]

... [Riel's] last words were to say good-bye to Dr. Jukes and thank him for his kindness, and just before the white cap was pulled over his face he said, "Remerciez Madame Forget." meaning "Thank Mrs. Forget".[84]

The cap was pulled down, and while he was praying the trap was pulled. Death was not instantaneous. Louis Riel's pulse ceased four minutes after the trap-door fell and during that time the rope around his neck slowly strangled and choked him to death. The body was to have been interred inside the gallows' enclosure, and the grave was commenced, but an order came from the Lieutenant-Governor to hand the body over to Sheriff Chapleau which was accordingly done that night.[84]

Following the execution, Riel's body was returned to his mother's home in St. Vital, where it lay in state. On 12 December 1886, his remains were laid in the churchyard of the Saint-Boniface Cathedral following the celebration of a requiem mass.

The trial and execution of Riel caused a bitter and prolonged reaction which convulsed Canadian politics for decades. The execution was both supported and opposed by the provinces. For example, conservative Ontario strongly supported Riel's execution, but Quebec was vehemently opposed to it. Francophones were upset Riel was hanged because they thought his execution was a symbol of Anglophone dominance of Canada. The Orange Irish Protestant element in Ontario had demanded the execution as the punishment for Riel's treason and his execution of Thomas Scott in 1870. With their revenge satisfied, the Orange turned their attention to other matters (especially the Jesuit Estates proposal). In Quebec there was no forgetting, and the politician Honoré Mercier rose to power by mobilizing the opposition in 1886.[85]

Revoking Riel's conviction

That Riel's name still has resonance in Canadian politics was evidenced on 16 November 1994, when Suzanne Tremblay, a Bloc Québécois member of parliament, introduced private members' bill C-228, "An Act to revoke the conviction of Louis David Riel".[86] The unsuccessful bill was widely perceived in English Canada as an attempt to arouse support for Quebec nationalism before the 1995 referendum on Quebec sovereignty.[86] Bill C-213 or Louis Riel Day Act and Bill C-417 Louis Riel Act are the more notable acts which have gone through parliament.[87] Bill C-297 to revoke the conviction of Louis Riel was introduced to the House of Commons 21 October and 22 November 1996, however the motion lacked unanimous consent from the House and was dropped.[88] Bill C-213[89] or the Louis Riel Day Act of 1997 attempted to revoke the conviction of Louis Riel for high treason and establish a National Day in his honour on 16 November.[89] or the Louis Riel Act which also had a first reading in parliament to revoke the conviction of Louis Riel, and establish 15 July as Louis Riel Day was tabled.[90]

| Bill | Parliament | Session | First Reading | Year |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| C-302 | 41 | 1 | September | 2011 |

| C-216 | 38 | 1 | October | 2004 |

| C-411 | 37 | 1 | January | 2001 |

| C-324 | 37 | 2 | September | 2002 |

| S-35 | 37 | 1 | January | 2001 |

| C-324 | 37 | 3 | February | 2004 |

| C-297 | November | 2006 | ||

| C-258 | May | 2006 | ||

| C-288 | March | 1995 | ||

| C-417 | June | 1998 | ||

| C-380 | 35 | 2 | March | 1997 |

| C-258 | 36 | 1 | 1997 | |

| C-257 | 36 | 2 | 1999 |

On 18 February 2008, the province of Manitoba officially recognized the first Louis Riel Day as a general provincial holiday. It will now fall on the third Monday of February each year in the Province of Manitoba.[91]

Historiography

Historians have debated the Riel case so often and so passionately that he is the most written-about person in all of Canadian history.[92] Interpretations have varied dramatically over time. The first amateur English language histories hailed the triumph of civilization, represented by English-speaking Protestants, over savagery represented by the half-breed Métis who were Catholic and spoke French. Riel was portrayed as an insane traitor and an obstacle to the expansion of Canada to the West.[93][94] By the mid-20th century academic historians had dropped the theme of savagery versus civilization, deemphasized the Métis, and focused on Riel, presenting his execution as a major cause of the bitter division in Canada along ethno cultural and geographical lines of religion and language. W. L. Morton says of the execution:

[It] gave rise to a bitter and prolonged reaction which convulsed the course of national politics for the next decade. In Ontario it had been demanded and applauded by the Orange element as the punishment of treason and a vindication of loyalty. In Quebec Riel was defended, despite his apostasy and megalomania, as the symbol, indeed as a hero of his race.[95]

Morton argued that Riel's demands were unrealistic:

[They] did touch on some real grievances, such as the need for increased representation of the people in the Council of the Territories, but they did not present a program of practical substance which the government might have granted without betrayal of its responsibilities. ... the Canadian government can hardly be blamed for refusing to continue its private negotiations with him, or for sending in the troops to suppress rebellion.[96]

The Catholic clergy had originally supported the Métis, but reversed themselves when they realized that Riel was leading a heretical movement. They made sure that he was not honored as a martyr.[97] However the clergy lost their influence during the Quiet Revolution, and activists in Québec found in Riel the perfect hero, with the image now of a freedom fighter who stood up for his people against an oppressive government in the face of widespread racist bigotry. He was made a folk hero by Métis, French Canadian and other Canadian minorities. Activists who espoused violence embraced his image; in the 1960s, the Quebec terrorist group, the Front de libération du Québec adopted the name "Louis Riel" for one of its terrorist cells.[98]

Across Canada there emerged a new interpretation of reality in his rebellion, holding that the Métis had major unresolved grievances; that the government was indeed unresponsive; that Riel resorted to violence only as a last resort; and he was given a questionable trial, then executed by a vengeful government.[99] John Foster said in 1985 that:

the interpretive drift of the last half-century ... has witnessed increasingly shrill though frequently uncritical condemnations of Canadian government culpability and equally uncritical identification with the "victimization" of the "innocent" Métis.[100]

However, a leading specialist Thomas Flanagan reversed his views after editing Riel's writings:

As I sifted the evidence this became less and less convincing to me until I concluded that the opposite was closer to the truth: that the Métis grievances were at least partly of their own making; that the government was on the verge of resolving them when the Rebellion broke out; that Riel's resort to arms could not be explained by the failure of constitutional agitation and that he received a surprisingly fair trial.[99]

Michael Hamon's thesis published in 2017 strongly refutes Flanagan's Riel and the Rebellion: 1885 Reconsidered book in the following terms:

Given, however, the Métis community’s hostility to the Catholic Church and Thomas Flanagan’s later work in Canadian courts, not to mention his inflammatory Riel and the Rebellion: Reconsidered (1983), it is no surprise that these “cultural history” works were, and continue to be, viewed sceptically [sic] by many Métis.[101]

Claude Bélanger, writer, editor, translator / transcriber, of Marianopolis College Quebec History Encyclopedia website's article titled "The 'Murder' of Thomas Scott" includes the following in his critique of Thomas Flanagan's works including in terms of an excerpt taken by Flanagan's Louis 'David" Riel. Prophet of the New World:

He has argued that Riel was both sane and guilty of what he was charged with in 1885. In the excerpt presented below, his critical views come out in the use of vocabulary: the Métis are said to be "insurgents" and the group is described as the "half-breeds". The use of this XIXth century derogatory term is usually banished in contemporary writings.[36]

As for the insanity, historians have noted that many religious leaders the past have exhibited behavior that looks exactly like insanity. Flanagan emphasizes that Riel exemplified the tradition of religious mystics involved in politics, especially those with a sense that the world was about to be totally transformed by their religious vision. In his case it meant his delivering the Métis from foreign domination. More broadly, Flanagan argues that Riel was devoutly religious and rejected equalitarianism (which he equated with secularism), concluding he was "a millenarian theocrat, sympathetic to the 'ancien régime' and opposed to the French Revolution, democracy, individualism, and secular society."[102][103]

Tom Nesmith concluding sentence of his book review for Flanagan's Louis 'David' Riel: 'Prophet of the New World:

Riel's chaotic "inner world" and the prosaic unfolding of events over the winter and spring of 1884-85 resist Flanagan's overarching millenarian interpretation.[104]

In an address delivered in 1964, George Stanley has this to say about Riel's insanity issue:

- In French: Ses idées, politiques et religieuses, furent sans doute très peu orthodoxes. Mais était-il si différent de ces grands personnages historiques qui eurent des visions depuis Jeanne d'Arc jusqu'au poète Shellay [sic]? Une chose est certaine; aujourd'hui on ne penserait pas à le pendre.[105]

- In English: His ideas, policies and religiosity were surely quite unorthodox. But was he so different from other grand historical figures who had visions ranging with Jeanne d'Arc to the poet Shelley? One this is certain; today no one would think to have his hanged.

Max Hamon's describes his dissertation approach as follows :

This intellectual biography tracks Riel's life across several "worlds," Indigenous and non-Indigenous, that Riel occupied over the course of his life and considers his formative years through four key themes: family, education, political culture, and networking. The tensions and pressures between these worlds allowed Riel to develop the cultural expertise necessary to challenge Canadian state hegemony. ... Using the cultural capital, social networks, and an intellectual "toolkit" he acquired over the course of his early years, Riel proposed a Confederation that would defend and represent the interests of the Métis.[106]

For example, Hamon addresses Miguel Joyal's stateman-like depiction of the 'new' statue on the grounds of the Manitoba legislature building thusly:

The Manitoba Metis Federation rejected this representation [i.e., earlier statue by Gaboury and Lemay] favoured a more statesman-like figure designed by Miguel Joyal. This statue represents the triumph of Riel and the continued presence of Métis in politics today. As a public statement by the Métis, it suggests a refusal of colonial domination.[107]

Another example has Hamon situating George Stanley's Louis Riel (1960) in the following preeminent historiographical terms:

Stanley’s Louis Riel, for which he had extensive access to the Riel Papers, appeared in 1960 and would become the benchmark for studies of Riel.[108]

Lastly, Hamon provides succinctly interesting insights linking the success and failure of Louis Riel and John A. Macdonald in relation to the recent toppling of the statue of John A. Macdonald in Montreal:[109]

The toppling of the statue of John A. Macdonald during a protest against policing in downtown Montreal last month was part of a global revolution in public opinion. As Peter Gossage remarked, “this is no longer Macdonald’s Canada.”

...

Settler state sovereignty is always predicated on the criminalization of Indigenous resistance.

...

At the first hint of trouble in the Northwest, in November 1869, John A. Macdonald presented some advice to William McDougall, the man appointed by the Canadian government to oversee the annexation of the Northwest ... .

- It occurs to me that you should ascertain from Governor McTavish to name two leading half-breeds in the Territory and inform them that you will take them into your council. This man Riel, who appears to be a moving spirit, is a clever fellow, and you should endeavor to retain him as an officer in your future police. If you do this promptly it will be a most convincing proof that you are not going to leave the half-breeds out of the Law.

...In the end, Riel’s success, rather than Macdonald’s failure, was a key part of why Canada turned first to Wolseley and then to the NWMP.

Legacy

Riel remains controversial. J. M. Bumsted in 2000 said that for Manitoba historian James Jackson, the murder of Scott – "perhaps the result of Riel's incipient madness – was the great blemish on Riel's achievement, depriving him of his proper role as the father of Manitoba."[110]

The Saskatchewan Métis' requested land grants were all provided by the government by the end of 1887, and the government resurveyed the Métis river lots in accordance with their wishes. The Métis did not understand the long term value of their new land, however, and it was soon bought by speculators who later turned huge profits from it. Riel's worst fears were realized—following the failed rebellion, the French language and Roman Catholic religion faced increasing marginalization in both Saskatchewan and Manitoba, as exemplified by the controversy surrounding the Manitoba Schools Question. The Métis themselves were increasingly forced to live on undesirable land or in the shadow of Indian reserves (as they did not themselves have treaty status). Saskatchewan did not become a province until 1905.

Riel's execution and Macdonald's refusal to commute his sentence caused lasting discord in Quebec, and led to a fundamental alteration in the Canadian political order.[111] In Quebec, Honoré Mercier[112] exploited the discontent to reconstitute the Parti National. This party, which promoted Quebec nationalism, won a majority in the 1886 Quebec election by winning a number of seats formerly controlled by the Quebec Conservative Party. The federal election of 1887 likewise saw significant gains by the federal Liberals, again at the expense of the Conservatives. This led to the victory of the Liberal party under Sir Wilfrid Laurier in the federal election of 1896, which in turn set the stage for the domination of Canadian federal politics by the Liberal party in the 20th century.

Commemorations

A resolution was passed by Parliament on 10 March 1992 citing that Louis Riel was the founder of Manitoba.[113]

Two statues of Riel are located in Winnipeg.[114] One of these statues, the work of architect Étienne Gaboury and sculptor Marcien Lemay, depicts Riel as a naked and tortured figure. It was unveiled in 1970 and stood in the grounds of the Manitoba Legislative Building for 23 years. After much outcry (especially from the Métis community) that the statue was an undignified misrepresentation, the statue was removed and placed at the Collège universitaire de Saint-Boniface.[115] It was replaced in 1994 with a statue of Louis Riel designed by Miguel Joyal depicting Riel as a dignified statesman. The unveiling ceremony was on 16 May 1996, in Winnipeg.[113]

A statue of Riel on the grounds of the Saskatchewan Legislative Building in Regina was installed and later removed for similar reasons.[116]

In numerous communities across Canada, Riel is commemorated in the names of streets, schools, neighbourhoods, and other buildings. Examples in Winnipeg include the landmark Esplanade Riel pedestrian bridge linking old Saint-Boniface with Winnipeg, the Louis Riel School Division, Louis Riel Avenue in Old Saint-Boniface, and Riel Avenue in St. Vital's Minnetonka neighbourhood (which is sometimes called Riel). The student centre and campus pub at the University of Saskatchewan in Saskatoon are named after Riel (Place Riel and Louis', respectively).[117][118] One of the student residences at Simon Fraser University in Burnaby, British Columbia is named Louis Riel House. There are schools named after Louis Riel in three major Canadian cities: Calgary, Ottawa and Winnipeg.[119][120][121] On 26 September 2007, Manitoba legislature passed a bill establishing a statutory holiday on the third Monday in February as Louis Riel Day, the same day some other provinces celebrate Family Day, beginning in 2008.[122]

In the spring of 2008, the Government of Saskatchewan Tourism, Parks, Culture and Sport Minister Christine Tell proclaimed in Duck Lake that "the 125th commemoration, in 2010, of the 1885 Northwest Resistance is an excellent opportunity to tell the story of the prairie Métis and First Nations peoples' struggle with Government forces and how it has shaped Canada today."[123] One of three Territorial Government Buildings remains on Dewdney Avenue in the Saskatchewan capital city of Regina, which was the site of the Trial of Louis Riel, where the drama the "Trial of Louis Riel" is still performed. Following the May trial, Louis Riel was hanged 16 November 1885. The RCMP Heritage Centre, in Regina, opened in May 2007.[124][125][126] The Métis brought his body to his mother's home, now the Riel House National Historic Site, and then interred in the churchyard of the St. Boniface Cathedral not far from where he was born.[127][128]

Arts, literature and popular culture

In 1925, the French writer Maurice Constantin-Weyer who lived 10 years in Manitoba published in French a fictionalized biography of Louis Riel titled La Bourrasque. An English translation/adaptation was published in 1930 : A Martyr's Folly (Toronto, The Macmillan Company), and a new version in 1954, The Half-Breed (New York, The Macaulay Compagny).[129]

Portrayals of Riel's role in the Red River Rebellion include the 1979 CBC television film Riel and Canadian cartoonist Chester Brown's acclaimed 2003 graphic novel Louis Riel: A Comic-Strip Biography.[130]

An opera about Riel entitled Louis Riel was commissioned for Canada's centennial celebrations in 1967. It was an opera in three acts, written by Harry Somers, with an English and French libretto by Mavor Moore and Jacques Languirand. The Canadian Opera Company produced and performed the first run of the opera in September and October 1967.[131]

From the late 1960s until the early 1990s, the city of Saskatoon hosted "Louis Riel Day", a summer celebration that included a relay race that combined running, backpack carrying, canoeing, hill climbing, horseback riding and a cabbage roll eating contest.

Billy Childish wrote a song entitled "Louis Riel", which was performed by Thee Headcoats. Texas musician Doug Sahm wrote a song entitled "Louis Riel," which appeared on the album S.D.Q. '98.[132] In the song, Sahm likens the lore surrounding Riel to David Crockett's legend in his home state, spinning an abridged tale of Riel's life as a revolutionary: "... but you gotta respect him for what he thought was right ... And all around Regina they talk about him still – why did they have to kill Louis Riel?"[133]

On 22 October 2003, the Canadian news channel CBC Newsworld and its French-language equivalent, Réseau de l'information, staged a simulated retrial of Riel.[134] Viewers were invited to enter a verdict on the trial over the internet, and more than 10,000 votes were received—87% of which were "not guilty".[135] The results of this straw poll led to renewed calls for Riel's posthumous pardon. Also on the basis of a public poll, the CBC's Greatest Canadian project ranked Riel as the 11th "Greatest Canadian".[136]

See also

- Aboriginal Canadian personalities

- History of Manitoba

- List of Canadian First Nations leaders

- Métis National Council

- The Canadian Crown and Aboriginal peoples

Footnotes

- ^ library.usask.ca/northwest online, Louis Riel

- ^ a b c d e f g h Thomas 1982

- ^ pwnhc.ca, History of the Name of the Northwest Territories

- ^ Bumsted 1987, pp. 47–54

- ^ Betts 2008, p. 19

- ^ SHSB i Online, See Provisional Government section.

- ^ Bumsted 1992, pp. xiii, 31

- ^ a b c d Stanley & Gaudry 2013

- ^ Bumsted & Smyth 2013

- ^ Hamon 2017, p. 51

- ^ umanitoba.ca 2005, Grade 6 - Louis Riel and the Metis

- ^ a b pc.gc.ca/lhn-nhs/mb 2005, Riel House National Historic Site

- ^ Stanley 1963, pp. 13–20

- ^ Mitchell 1952a, Part 1 of 2

- ^ SHSB i Online, See His family, his youth section.

- ^ Stanley 1963, pp. 26–28

- ^ MNO (2006). "Louis Riel". Métis Nation of Ontario. Archived from the original on 7 July 2007.

- ^ Stanley 1963, p. 33

- ^ Stanley 1963, pp. 13–34

- ^ Dorge 1969, Taché & Confederation

- ^ Read i 1982, The Red River Rebellion and J. S. Dennis

- ^ Paquin, Young & Préfontaine, pp. 5–7

- ^ familysearch.org, Manitoba Land Records, Part 1

- ^ Gabriel Dumont Institute (1985). "Reading #9 - National Committee of the Métis". Archived from the original on 31 August 2007.

- ^ CBC (2001). "From Sea to Sea / The Métis Resistance / Louis Riel".

- ^ CBC (2001). "From Sea to Sea / The Execution of Thomas Scott".

- ^ "John Christian Schultz". Virtual American Biographies. Evisum Inc. 2000.

- ^ "Louis Riel". Virtual American Biographies. Evisum Inc. 2000. Archived from the original on 22 February 2006. Retrieved 25 September 2007.

- ^ "Metis culture 1869". Metis History. Dead link

- ^ Mitchell 1960

- ^ Reford 1998

- ^ Bumsted & Foot 2015

- ^ Campbell 2018, Review of Ian MacKay's Reasoning Otherwise. [dubious – discuss]

- ^ "Local Laws". Vol I No. 18. New Nation. 15 April 1870. p. 3.

- ^ Indigenous & Northern Relations, Legislative Assembly of Assiniboia

- ^ a b Bélanger 2007, The 'Murder' of Thomas Scott

- ^ Boulton 1985, p. 51

- ^ Anastakis 2015, p. 27

- ^ Dick 2004

- ^ Maton 1993, Métis Nation Land and Resource Rights

- ^ Maton, Manitoba Act, 1870

- ^ Manitoba Commemorative Plaque for The Wolseley Expedition

- ^ Bowles 1968

- ^ Swan & Jerome 2000

- ^ Gwyn 2011, pp. 150–151

- ^ Virtual Museum online, Louis Riel (1844-1885): Biography

- ^ Marleau, Montpetit & parl.gc.ca / Commons Notes 2000, Notes 351–373

- ^ a b Linder & famous-trials.com online, A Biography of Louis Riel

- ^ Betts 2008, p. 16

- ^ a b cbc.ca/archives (2006). "Rethinking Riel – Was Louis Riel Mentally Ill?". CBC Archives.

- ^ Hird 2004, The Passion of Louis Riel

- ^ Stanley et al. 1985, p. 265, Note 2

- ^ SHSB ii Online 2020, L'arbre généalogique de Louis Riel

- ^ Payment 1980, p. 130, Fig. 10 Métis settlement, Montana Territory

- ^ Morton 1976, Riel, Louis (1817-64)

- ^ Marriage Certificate Louis Riel & Marguerite Monet

- ^ LAC, Canadian Confederation, Louis Riel (October 22, 1844 - November 16, 1885)

- ^ Flanagan 1991

- ^ Gaudry 2007

- ^ Smyth 1998

- ^ indians.org. "Big Bear".

- ^ Yanko, Dave; virtualsk.com. "Cree Chief Poundmaker".

- ^ library.usask.ca/northwest online, Louis Riel to W. Jackson 22 September 1884 / Call No. MSS C555/2/13.7d

- ^ library.usask.ca/northwest online, Jackson, William Henry to Friend? 21 January 1885 / Call No. MSS C555/2/13.9e

- ^ Titley 1998, Edgar Dewdney

- ^ Miller i 2004, p. 44

- ^ Creighton 1970, p. 54

- ^ Payment 1994

- ^ Dumontet 1994, See Mnemographia Canadensisfor year.

- ^ a b Linder & famous-trials.com online, Final Statement of Louis Riel at his trial in Regina, 1885

- ^ Louis Riel: A Brief Chronology

- ^ Virtual Museum, Why did the 1885 Resistance Happen?

- ^ Virtual Museum, The Battle of Fish Creek (April 23, 1885)}}

- ^ Beal, MacLeod & Foot 2006

- ^ Mein 2006, North-West Resistance Online

- ^ Basson 2008, p. 66

- ^ Linder & famous-trials.com online, The Trial of Louis Riel: A Chronology

- ^ Stanley 1979, p. 23

- ^ a b Boulton 1886, p. 411

- ^ Littmann 1978, p. 461

- ^ Bélanger 2007, North-West Rebellion

- ^ LAC, Louis Riel (October 22, 1844 - November 16, 1885)

- ^ Boulton 1886, p. 413

- ^ a b Boulton 1886, p. 414

- ^ Stewart 2002, p. 156

- ^ a b Linder & famous-trials.com online, Act to Revoke the Conviction of Louis Riel BILL C-288 (First Reading)

- ^ a b Legisinfo, Bill Re-Introduced

- ^ "Act to revoke the conviction of Louis Riel". Archived from the original on 30 November 2007.

- ^ a b House of Commons of Canada Bill C-213

- ^ Préfontaine, Riel, Louis "David" (1844-85)

- ^ Manitoba - Louis Riel Day holiday (3rd Mon. in Feb.)

- ^ Owram 1994, p. 18

- ^ Francis, Jones & Smith 2009, pp. 306–307

- ^ Sprague 1988, p. 1

- ^ Morton 1963, p. 371

- ^ Morton 1963, p. 369

- ^ Perin 1990, p. 259

- ^ Saywell 1973, p. 94

- ^ a b Flanagan 2000, p. x

- ^ Foster 1985, pp. 259–260

- ^ Hamon 2017, p. 17

- ^ Flanagan 1986, pp. 219–228

- ^ Mossmann 1985

- ^ Nesmith 1979

- ^ Stanley 1964, p. 26

- ^ Hamon 2017, abstract excerpt

- ^ Hamon 2017, p. 25

- ^ Hamon 2017, p. 15

- ^ Hamon 2020

- ^ Bumsted 2000, p. 17

- ^ Wade 1968, pp. 416–423

- ^ Lindsay 1911

- ^ a b parl.gc.ca / Hansard Debates 1996, Bill C297

- ^ Bower 2001, Practical Results

- ^ Mattes 1998, Ch. 1 : The controversy over Marcien Lemay's sculpture of Louis Riel and Métis Nationhood

- ^ Mattes 1998, Ch. 2, pp. 51-69

- ^ University of Saskatchewan, Place Riel opens

- ^ Tourism Saskatchewan, Scenic Routes – The Louis Riel Trail

- ^ "Calgary's Louis Riel School".

- ^ "Ottawa's école secondaire publique Louis-Riel".

- ^ "Winnipeg's Collège Louis-Riel".

- ^ CBC News, Manitoba's new holiday: Louis Riel Day

- ^ Government of Saskatchewan, Tourism agencies to celebrate the 125th anniversary of the Northwest Resistance/Rebellion

- ^ Saskatchewan Genealogical Society, Regina History Guide Tour

- ^ library.usask.ca online; Leader-Post (1955). "RCMP traditions centre in Regina".

- ^ History of the Royal Canadian Mounted Police

- ^ Manitoba Commemorative Plaque for Louis Riel

- ^ mhs.mb.ca 1995, Red River Resistance

- ^ BAnQ, Dictionnaire des auteurs de langue française en Amérique du Nord

- ^ Linder & famous-trials.com online, The Story of Louis Riel: Excerpts from a Comic-Strip Biography

- ^ National Library of Canada Music Archive for Somers, Harry, 1925–1999

- ^ Sahm, Doug; youtube.com (2011). "Louis Riel".

- ^ Album review by Eugene Chadbourne

- ^ Strange 2006, Crime, Media, Culture

- ^ Muise 2002, CSHC Celebratory Opening

- ^ CBC Great Canadians 2007

Bibliography

- Anastakis, Dimitry (2015). Death in the Peaceable Kingdom: Canadian History since 1867 through Murder, Execution, Assassination, and Suicide. University of Toronto Press. p. 27. ISBN 9781442606364.

- Barkwell, Lawrence J.; Dorion, Leah; Prefontaine, Darren (2001). Metis Legacy: A Historiography and Annotated Bibliography. Winnipeg / Saskatoon: Pemmican Publications Inc. / Gabriel Dumont Institute. ISBN 1-894717-03-1. Historiography.

- Barrett, Matthew (2014). ""Hero of the Half-Breed Rebellion": Gabriel Dumont and Late Victorian Military Masculinity". Journal of Canadian Studies / Revue d'études canadiennes. 48 (3): 79–107. doi:10.3138/jcs.48.3.79. S2CID 145605358. [under discussion]

- Basson, Lauren L. (2008). White enough to be American?. University of North Carolina Press. ISBN 978-0-8078-5837-0.

- Beal, Bob; MacLeod, Rod; Foot, Richard (2006). "North-West Rebellion". The Canadian Encyclopedia. Historica Canada. Retrieved 5 January 2016.

- Bélanger, Claude (2007). The Quebec History Encyclopedia. Marianopolis College.

- Betts, Gregory (2008). "Non Compos Mentis: A Meta-Historical Survey of the Historiographic Narratives of Louis Riel's 'Insanity'" (PDF). International Journal of Canadian Studies / Revue internationale d'études canadiennes (38): 15–40. doi:10.7202/040805ar. Historiography. [under discussion]

- Boulton, Charles Arkoll (1886). Reminiscences of the North-West Rebellions. Toronto: Grip Printing & Publishing Co. A first person account record of the raising of Her Majesty's 100th Regiment in Canada and a chapter on Canadian social & political life.

- Boulton, Charles Arkoll (1985). Robertson, Heather (ed.). I Fought Riel. James Lorimer & Company. ISBN 0-88862-935-4.

- Bowles, Richard S. (1968). "Adams George Archibald, First Lieutenant-Governor of Manitoba". MHS Transactions. 3 (25 1968–69 season). Manitoba Historical Society. Retrieved 23 September 2007.

- Braz, Albert (2003). The False Traitor: Louis Riel in Canadian Culture (review). University of Toronto Press. Historiography.

- Brown, Chester (2003). Louis Riel: A Comic-strip Biography. Montreal: Drawn & Quarterly. ISBN 1-896597-63-7. A biography of Riel in the form of a graphic novel.

- Bruyneel, Kevin (2010). "Exiled, Executed, Exalted: Louis Riel, "Homo Sacer" and the Production of Canadian Sovereignty". Canadian Journal of Political Science. 43 (3): 711–732. doi:10.1017/S0008423910000612. JSTOR 40983515. Historiography.

- Bumsted, J. M. (1987). "The 'Mahdi' of Western Canada: Lewis Riel and His Papers". The Beaver. 67 (4): 47–54. Historiography.

- Bumsted, J. M. (1992). The Peoples of Canada: A Post-Confederation History.

- Bumsted, J. M. (2000). Thomas Scott's Body: And Other Essays on Early Manitoba History. University of Manitoba Press. ISBN 9780887553875.

- Bumsted, J. M.; Smyth, Julie (2013) [2016]. "Red River Colony". The Canadian Encyclopedia (online ed.). Historica Canada. Retrieved 5 January 2016.

- Bumsted, J. M.; Foot, Richard (2015) [2019]. "Red River Rebellion". The Canadian Encyclopedia (online ed.). Historica Canada. Retrieved 5 January 2016.

- Campbell, Colin J. (2018). "Progressive" Canadian Politics and the Paroxysm of Identity". TOPIA: Canadian Journal of Cultural Studies. 30–31. doi:10.3138/topia.30-31.319.

- pc.gc.ca/lhn-nhs/mb (2005). "Riel House National Historic Site of Canada". Parks Canada. Archived from the original on 14 April 2005. Retrieved 5 January 2007.

- parl.gc.ca / Hansard Debates (1996). "Private Members' Business regarding An Act to Revoke the Conviction of Louis David Riel - Bill C297". Hansard Debates for Friday, November 22, 1996. House Publications Parliament of Canada. Retrieved 15 November 2007.

- Marleau, Robert; Montpetit, Camille; parl.gc.ca / Commons Notes (2000). "House of Commons Procedure and Practice The House of Commons and Its Members – Notes 351–373". Parliament of Canada. Retrieved 23 September 2007.

- Careless, J.M.S. (1991). Canada: A story of challenge. Stoddart. ISBN 0-7736-7354-7. A survey of Canadian history.

- CBC Great Canadians (2007). "Meet the Greatest Canadian – Top 11 to 100". CBC. Archived from the original on 9 November 2007. Retrieved 14 November 2007.

- Creighton, Donald (1970). Canada's First Century: 1867–1967.

- Dick, Lyle (2004). "Nationalism and Visual Media in Canada: The Case of Thomas Scott's Execution". Manitoba History. 48 (Autumn/Winter): 2–18. Historiography.

- Dumontet, Monique (1994). "Essay 16 Controversy in the Commemoration of Louis Riel". Mnemographia Canadensis. 2. University of Western Ontario Department of English. Retrieved 14 December 2019.

- Dorge, Lionel (1969). "Bishop Taché and the Confederation of Manitoba, 1969–1970". MHS Transactions. 3 (26 1969-70 season). Manitoba Historical Society. Retrieved 13 November 2007.

- familysearch.org. "Manitoba Land Records, Part 1". Retrieved 5 December 2020.

- Flanagan, Thomas (1979). Louis 'David' Riel: prophet of the new world. University of Toronto Press, Toronto. ISBN 0-88780-118-8. An influential work portraying Riel as a religious prophet and responsible for the rebellion; highly controversial among Riel admirers.

- Flanagan, Thomas (1983). Riel and the Rebellion. Saskatoon: Western Producer Prairie Books. ISBN 0-88833-108-8.

- Flanagan, Thomas (1986). "Louis Riel: Icon of the Left". Transactions of the Royal Society of Canada. 1: 219–228.

- Flanagan, Thomas (1991). "Louis Riel's Land Claims". Manitoba History. 21 (Spring). Manitoba Historical Society. Retrieved 24 September 2007.

- Flanagan, Thomas (1992). Louis Riel. Ottawa: Canadian Historical Association. ISBN 0-88798-180-1. A short work highlighting the complexity of Riel's character.

- Flanagan, Thomas (2000). Riel and the Rebellion: 1885 Reconsidered (2nd ed.). University of Toronto Press. ISBN 0802082823., 256 pages, Historiography.

- Francis, R. Douglas; Jones, Richard; Smith, Donald B., eds. (2009). Journeys: A History of Canada. Cengage Learning. ISBN 9780176442446.

- Foster, John E. (1985). "Review of Riel and the Rebellion 1885 Reconsidered By Thomas Flanagan". Great Plains Quarterly. 5 (4): 259–60.

- Gaudry, Adam (2007). "Gabriel Dumont". The Canadian Encyclopedia (online ed.). Historica Canada. Retrieved 5 January 2016.

- Goulet, George R. D. (2005). The Trial of Louis Riel, Justice and Mercy Denied. Calgary: FabJob. ISBN 1-894638-70-0. A critical legal and political analysis of Riel's 1885 high treason trial.

- Gwyn, Richard J. (2011). Nation Maker: Sir John A. Macdonald: His Life, Our Times. Life and Times of Sir John A. Macdonald Series. Vol. Vol. 2 of 2.

{{cite book}}:|volume=has extra text (help) - Hamon, Max (2017). The many worlds of Louis Riel: a political odyssey from Red River to Montreal and back 1840-1875 (PhD thesis). McGill University.

- Hamon, Max (2020). "Success/Failure? Louis Riel and the History of Policing Canada". Borealia /Early Canadian History.

- Hansen, Hans (2014). Riel's Defence: Perspectives on His Speeches (1st ed.). McGill-Queen's University Press. ISBN 9780773543362. 344 pages paper.

- Hird, Ed, The Reverend (2004). "The Passion of Louis Riel". Deep Cove Crier. St. Simon's Anglican Church. Archived from the original on 27 January 2009. Retrieved 15 November 2007.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Huet, Raymond (1985). "The Clergyman as Historian: the Rev. A.-G. Morice, O.M.I., and Riel Historiography". CCHA Historical Studies. 52. University of Lethbridge: 83–96. Historiography.

- Kinsey, Howard Joseph (1952). Strange Empire: A Narrative of the Northwest (Louis Riel and the Metis People). William Morrow & Co, New York. ISBN 0-87351-298-7. First reasonably accurate biography of Louis Riel to be written. An exhaustive, "objective" yet sympathetic scholarly account.

- Knox, Olive. "The Question of Louis Riel's Insanity". Manitoba Historical Society Transactions. 3 (6): 1949–50.

- Linder, Douglas O.; famous-trials.com online. "Louis Riel Trial (1885)". University of Missouri Kansas City School of Law. Retrieved 10 December 2020. Homepage.

- Lindsay, Lionel (1911). "Louis-Honoré Mercier". The Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol. X. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

- Littmann, S.K. (1978). "Symposium - Riel Revisited / A Pathography of Louis Riel". Can. Psychiatr. Assoc. J. 23 (7). Canada Psychiatric Association: 449–462. doi:10.1177/070674377802300706. PMID 361196. S2CID 31438889.

- mhs.mb.ca (1995). "Red River Resistance". Manitoba History. 29 (Spring 1995). Manitoba Historical Society. Retrieved 20 September 2009.

- umanitoba.ca (2005). "Grade 6 - Louis Riel and the Metis". Canadian Wartime Experiences. University of Manitoba. Archived from the original on 6 January 2007. Retrieved 23 September 2007.

- Martin, Sandra (2012). "Material history: The rope that hanged Louis Riel". The Globe and Mail. Retrieved 18 March 2016.

- Mattes, Catherine L. (1998). Whose Hero? Images of Louis Riel in Contemporary Art and Métis Nationhood (PDF) (M.Sc. thesis). Montreal: Concordia University. Retrieved 13 December 2020.

- Mein, Stewart (2006). "North-West Resistance". The Encyclopedia of Saskatchewan. University of Regina.

- Maton, William F. (ed.). Manitoba Act, 1870. The Solon Law Archive. Retrieved 23 September 2007.

- Maton, William F, ed. (1993). "Chapter 5 Métis Perspective, Appendix 5C: Métis Nation Land and Resource Rights". Report of the Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples, Perspective and Realities. Indian and Northern Affairs Canada. Archived from the original on 1 October 2006. Retrieved 14 November 2007.

- Miller, J. R. (1988). "From Riel to the Metis". Canadian Historical Review. 69 (1): 1–20. doi:10.3138/CHR-069-01-01. S2CID 154383622. Historiography.

- Miller i, James Rodger (2004). Reflections on Native-newcomer Relations: Selected Essays (2nd ed.). University of Toronto Press.

- Miller ii, J. R. (2004). "Reflections on Native-newcomer Relations: Selected Essays". In Miller, J. R. (ed.). From Riel to the Métis. University of Toronto Press. Historiography - p. 37-38, 39–60.

- Mitchell, Ross (1960). "John Christian Schultz, M.D. – 1840–1896". Manitoba Pageant. 5 (2). Retrieved 23 September 2007. Posted now on mhs.mb.ca website.

- Mitchell, W.O. (1952a). "The Riddle of Louis Riel Part 1". MacLean's.

- Morton, Desmond (1972). The last war drum : the North West campaign of 1885. Military history of 1885.

- Morton, Desmond (May 1998). "Image of Louis Riel in 1998". Canadian Speeches. 12 (2). Historiography.

- Morton, William Lewis (1963). The Kingdom of Canada: A General History from Earliest Times. McClelland and Stewart.

- Morton, W. L. (1976). "Riel, Louis (1817-64)". Dictionary of Canadian Biography. Vol. 9. University of Toronto / Université Laval. Retrieved 3 December 2020.

- Mossmann, Manfred (1985). "The Charismatic Pattern: Canada's Riel Rebellion of 1885 as a Millenarian Protest Movement". Prairie Forum. 10 (2): 307–325. Historiography.

- Muise, Del (2002). "Media and Public History: Canada: A People's History". Centre for the Study of Historical Consciousness. University of British Columbia. Archived from the original on 25 May 2005. Retrieved 14 November 2007.

- mysteriesofcanada.com, Bruce; Ricketts (2007). "Louis Riel – Martyr, hero or traitor?". Archived from the original on 8 July 2007. Retrieved 23 September 2007.

- Owram, Doug, ed. (1994). Canadian history : a reader's guide: Confederation to the present. University of Toronto Press. ISBN 9780802076762. Historiography - pp. 18, 168, 191–195, 347–350.

- Paquin, Todd; Young, Patrick; Préfontaine, Darren R. "Métis Farmers" (PDF). Métis Museum. Retrieved 5 December 2020.

- Nesmith, Tom (1979). "Book review for Tom Flanagan's Louis 'David' Riel: Prophet of the New World". Archivaria. 9 (Winter).

- Payment, Diane (1980). Riel Family: Home and Lifestyle at St-Vital, 1860-1910 [Manuscript Report Number 379] (PDF). Parks Canada, Historical Research Division, Prairie Region. 138 pages. Map of Figure 10 points east of mouth of Rivière au Lait & Missouri River towards Ft. Berthold, Dakota Territory and/or Pointe au Loup.

- Payment, Diane P. (1994). "Nolin, Charles". Dictionary of Canadian Biography. Vol. 13. University of Toronto / Université Laval. Retrieved 24 September 2007.

- Perin, Roberto (1990). Rome in Canada: The Vatican and Canadian Affairs in the Late Victorian Age. p. 259.

- Préfontaine, Darren R. "Riel, Louis "David" (1844–85) Online". Encyclopedia of Saskatchewan. Canadian Plains Research Center, University of Regina. Retrieved 8 December 2020.

- Préfontaine, Darren R.; Dorion, Leah (2003). "The Métis and the Spirit of Resistance". Gabriel Dumont Institute. Retrieved 22 December 2020. Historiography.

- pwnhc.ca. "History of the Name of the Northwest Territories". Prince of Wales Northern Heritage Center. Retrieved 3 December 2020.

- Read i, Colin (1982). "The Red River Rebellion and J. S. Dennis, "Lieutenant and Conservator of the Peace"". Manitoba History (3). Huron College, University of Western Ontario / Manitoba Historical Society. Retrieved 13 November 2007.

- Read, Geoff; Webb, Todd (2012). "'The Catholic Mahdi of the North West': Louis Riel and the Metis Resistance in Transatlantic and Imperial Context". Canadian Historical Review. 93 (2): 171–195.

- Reford, Alexander (1998). "Smith, Donald Alexander, 1st Baron Strathcona and Mount Royal". Dictionary of Canadian Biography. Vol. 14. Retrieved 23 September 2007.

- Reid, Jennifer; Long, Charles; Carrasco, David (2008). Louis Riel and the Creation of Modern Canada: Mythic Discourse and the Postcolonial State (illustrated ed.). Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press. ISBN 978-0-8263-4415-1. 314 pages, Historiography.

- Saywell, John T., ed. (1973). Canadian Annual Review of Politics and Public Affairs: 1971. University of Toronto Press.

- Bower, Shannon (2001). ""Practical Results": The Riel Statue Controversy at the Manitoba Legislative Building". Manitoba History. 42 (Autumn / Winter 2001–2002). Manitoba Historical Society. Retrieved 24 September 2007.

- Siggins, Maggie (1994). Riel: a life of revolution. Toronto: HarperCollins. ISBN 0-00-215792-6. A sympathetic reevaluation of Riel drawing heavily on his own writings.

- Smyth, David (1998). "Isbister, James". Dictionary of Canadian Biography. Vol. 14. Retrieved 23 September 2007.

- SHSB i Online, Centre du patrimoine. "Louis Riel - One Life, One Vision" (PDF). Société historique de Saint-Boniface. Retrieved 8 December 2020.

- SHSB ii Online, Centre du patrimoine (2020). "L'arbre généalogique de Louis Riel" (PDF). Société historique de Saint-Boniface.

- Sprague, D.N. (1988). Canada and the Métis, 1869-1885. Historiography - Historiographical introduction pp. 1–17.

- library.usask.ca/northwest online. "Northwest Resistance Database". University of Saskatchewan. Retrieved 15 November 2007.

- Stanley, George (1963). Louis Riel. Toronto: McGraw-Hill Ryerson. ISBN 0-07-092961-0. The book that became the benchmark for later studies of Riel.

- Stanley, G. F. G. (1964). "Louis Riel". Revue d'histoire de l'Amérique française. 18 (1): 14–26. doi:10.7202/302338ar.

- Stanley, George F.G. (1979). Louis Riel: Patriot or Rebel? [Canadian Historical Association Booklet No. 2] (PDF) (9th ed.). Ottawa: Public Archives. ISBN 0-88798-003-1. Historiography.

- Stanley, George F. G.; Gaudry, Adam (2013). "Louis Riel". The Canadian Encyclopedia (online ed.). Historica Canada.

- Stanley, George F. G.; Huel, Raymond J.A.; Martel, Gilles; Flanagan, Thomas; Campbell, Glen, eds. (1985). The collected writings of Louis Riel / Les Écrits Complets de Louis Riel. University of Alberta Press. ISBN 0-88864-091-9. Essential reading for anyone wanting to understand Riel and his influence on the history of Western Canada.

- Stewart, Roderick (2002). Wilfrid Laurier. Dundurn. ISBN 9781770707559.

- Strange, Carolyn (2006). "Hybrid history and the retrial of the painful past" (PDF). Crime, Media, Culture. 2 (2). Sage Publications Australian National University: 197–215. doi:10.1177/1741659006065419. S2CID 146735290. Retrieved 14 November 2007.

- Swan, Ruth; Jerome, Edward A. (2000). "'Unequal justice:' The Metis in O'Donoghue's Raid of 1871". Manitoba History (39 Spring / Summer). Posted here in mhs.mb.ca website.

- Thistle, Jesse (2014). "The 1885 Northwest Resistance: Causes to the Conflict". HPS History and Political Science Journal. 3.