United States chemical weapons program

The United States chemical weapons program began in 1917 during World War I with the creation of the U.S. Army's Gas Service Section and ended 73 years later in 1990 with the country's practical adoption of the Chemical Weapons Convention (signed 1993; entered into force, 1997). Destruction of stockpiled chemical weapons began in 1985 and is still ongoing. The U.S. Army Medical Research Institute of Chemical Defense (USAMRICD), at Aberdeen Proving Ground, Maryland, continues to operate.

History

The U.S. had participated in the formulations of the Hague Conventions of 1899 and 1907 which banned chemical warfare, among other things, but the U.S. never joined the article which prohibited chemical weapons.

World War I

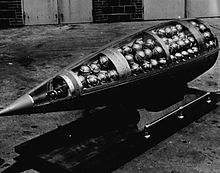

In World War I, the U.S. established its own chemical weapons research facility and produced its own chemical munitions.[1] It produced 5,770 metric tons of these weapons, including 1,400 metric tons of phosgene and 175 metric tons of mustard gas. This was about 4% of the total chemical weapons produced for that war and only just over 1% of the era's most effective weapon, mustard gas. (U.S. troops suffered less than 6% of gas casualties.)[2] The U.S. also established the First Gas Regiment, which left Washington, D.C. on Christmas Day, 1917, and arrived at the front in May 1918.[1] During its time in France, the First Gas Regiment used phosgene in a number of attacks.[3]

The United States began large-scale production of an improved vesicant gas known as Lewisite, for use in an offensive planned for early 1919. Lewisite was a major American contribution to the chemical weapon arsenal of World War I, although it was not actually used in the field during World War I. It was developed by Captain Winford Lee Lewis of the U.S. Chemical Warfare Service in 1917.[2] (The Germans later claimed that they had manufactured it in 1917 prior to the American discovery.) By the time of the armistice on 11 November 1918, a plant near Willoughby, Ohio, was producing 10 tons per day of the substance, for a total of about 150 tons.[2] It is uncertain what effect this new chemical agent would have had on the battlefield, however, as it degrades in moist conditions.[4][5]

After the war, the U.S. was party to the Washington Arms Conference Treaty of 1922 which would have banned chemical weapons but failed because it was rejected by France. The U.S. continued to stockpile chemical weapons, eventually exceeding 30,000 tons of material.

World War II

Chemical weapons were not used by the U.S. or the other Allies during World War II; however, quantities of such weapons were deployed to Europe for use in case Germany initiated chemical warfare. At least one accident occurred: On the night of December 2, 1943, German Junkers Ju 88 bombers attacked the port of Bari in Southern Italy, sinking several American ships – among them John Harvey, which was carrying mustard gas. The presence of the gas was highly classified, and authorities ashore had no knowledge of it – which increased the number of fatalities, since physicians, who had no idea that they were dealing with the effects of mustard gas, prescribed treatment not consistent with those suffering from exposure and immersion. According to the U.S. military account, "Sixty-nine deaths were attributed in whole or in part to the mustard gas, most of them American merchant seamen" out of 628 mustard gas military casualties.[Navy 2006][Niderost] Civilian casualties were not recorded. The whole affair was kept secret at the time and for many years after the war. Large quantities of chemical weapons were also deployed to India, from where they could have been delivered to Japan by B-29 bombers. At the end of the war, over 50,000 mustard gas bombs, 10,000 phosgene bombs and other chemical munitions were dumped into deep water in the Bay of Bengal.[6]

Cold War

After the war, the Allies recovered German artillery shells containing three new nerve agents developed by the Germans (Tabun, Sarin, and Soman), prompting further research into nerve agents by all of the former Allies. Thousands of American soldiers were exposed to chemical warfare agents during Cold War testing programs (see Edgewood Arsenal human experiments), as well as in accidents. In 1968, one such accident killed approximately 6,400 sheep when an agent drifted out of Dugway Proving Ground during a test.[7]

The U.S. also investigated a wide range of possible nonlethal, psychobehavioral chemical incapacitating agents including psychedelic indoles such as lysergic acid diethylamide (also experimenting to see if it could be used for effective mind control) and marijuana derivatives, certain tranquilizers like ketamine or fentanyl, as well as several glycolate anticholinergics. One of the anticholinergic compounds, 3-quinuclidinyl benzilate, was assigned the NATO code BZ and was weaponized at the beginning of the 1960s for possible battlefield use. This agent was allegedly employed by American troops as a counterinsurgency weapon in the Vietnam War but the U.S. maintains that this agent never saw operational use.[8] The North Koreans and Chinese have alleged that chemical and biological weapons were used by the United States in the Korean War;[9] but the United States' denial is supported by Russian archival documents.[10]

The growing protests over the U.S. role in the Vietnam War, the use of defoliants there, and the use of riot control agents both in Southeast Asia and inside the U.S. (as well as heightened concern for the environment) all gradually increased public hostility in the U.S. toward chemical weapons in the 1960s. Three events particularly galvanized public attention: a 1968 sheep-kill incident at Dugway Proving Ground, Operation Cut Holes and Sink ‘Em (CHASE) — a program involving disposal of unwanted munitions at sea — and a 1969 accident with sarin at Okinawa.[11]

Renunciation

On November 25, 1969, President Richard Nixon unilaterally renounced the first use of chemical weapons and renounced all methods of biological warfare.[12] He issued a unilateral decree halting production and transport of chemical weapons which remains in effect. From 1967 to 1970 in Operation CHASE, the U.S. disposed of chemical weapons by sinking ships laden with the weapons in the deep Atlantic. The U.S. began to research safer disposal methods for chemical weapons in the 1970s, destroying several thousand tons of mustard gas by incineration at Rocky Mountain Arsenal and nearly 4,200 tons of nerve agent by chemical neutralization at Tooele Army Depot and Rocky Mountain Arsenal.[13]

The U.S. entered the Geneva Protocol in 1975 at the same time it ratified the Biological Weapons Convention. This was the first operative international treaty on chemical weapons that the United States was party to.

In May 1991, President George H.W. Bush unilaterally committed the United States to destroying all chemical weapons and renounced the right to chemical weapon retaliation. In 1993, the United States signed the Chemical Weapons Convention, which required the destruction of all chemical weapon agents, dispersal systems, and chemical weapons production facilities by April 2012. In 1997, the United States formally agreed to destroy its stockpile by ratifying the Chemical Weapons Convention. The international treaty bans the use of all chemical weapons and aims to eliminate them throughout the world.

Decommissioning and destruction

The U.S. began stockpile reductions in the 1980s, removing some outdated munitions and destroying its entire stock of BZ beginning in 1988. In June 1990, Johnston Atoll Chemical Agent Disposal System began destruction of chemical agents stored on Johnston Atoll in the Pacific, seven years before the Chemical Weapons Convention came into effect. In 1986, President Ronald Reagan made an agreement with Chancellor Helmut Kohl to remove the U.S. stockpile of chemical weapons from Germany. As part of Operation Steel Box, in July 1990, two ships were loaded with over 100,000 shells containing GB and VX taken from U.S. Army weapons storage depots such as Miesau and then-classified ammunition FSTS (forward storage/transportation sites) and transported from Bremerhaven, Germany, to Johnston Atoll in the Pacific, a 46-day nonstop journey.[14]

The U.S. prohibition on the transport of chemical weapons as part of the Chemical Weapons Convention meant that destruction facilities had to be constructed at each of the U.S. nine storage facilities.

Congress established the Assembled Chemical Weapons Assessment (ACWA) program in 1996 to safely test and demonstrate at least two alternative technologies to the baseline incineration process for the destruction of the nation’s remaining stockpile of assembled chemical weapons.[15] Beginning in 1999, ACWA was tasked by the Secretary of Defense to demonstrate six incineration alternatives to destroy the remaining U.S. chemical weapons stockpile stored at the Blue Grass Army Depot in Kentucky and the U.S. Army Pueblo Chemical Depot in Colorado, the final two stockpiles in the United States. By 2000, ACWA had demonstrated six technologies. Neutralization followed by biotreatment was selected for the Colorado stockpile, and neutralization followed by supercritical water oxidation was selected for the Kentucky stockpile.

The U.S. met the first three of the treaty's four deadlines, destroying 45% of its stockpile of chemical weapons by 2007. By January 2012, the final treaty deadline, the United States had destroyed 89.75% of the original stockpile.[16] Only the stockpiles in Kentucky and Colorado remained. Both ACWA facilities are scheduled to complete chemical weapons destruction by the Chemical Weapons Convention treaty commitment of Sept. 30, 2023. U.S. Public Law mandates stockpile destruction by Dec. 31, 2023.[17]

As of September 2021, more than three-quarters of the Colorado stockpile and nearly one-third of the Kentucky stockpile had been destroyed.

Treaties

The United States was a party to some of the earliest modern chemical weapons ban treaties, the Hague Conventions of 1899 and 1907 and the Washington Arms Conference Treaty of 1922 although this treaty was unsuccessful. The U.S. ratified the Geneva Protocol which banned the use of chemical and biological weapons on January 22, 1975. In 1989 and 1990, the U.S. and the Soviet Union entered an agreement to end their chemical weapons programs, including "binary weapons". The United States ratified the 1993 Chemical Weapons Convention, which came into force in April 1997. This banned the possession of most types of chemical weapons. The United States and Russia possess the largest remaining chemical stockpiles among Convention members according to the Centre for Arms Control and Non-proliferation, as of 2014.[citation needed] The convention also banned chemical weapons development, and requires the destruction of existing stockpiles, precursor chemicals, production facilities and weapon delivery systems.

Chemical weapons disposal

Disposal of chemical munitions has concluded at seven of the U.S.'s nine chemical depots (89.75% stockpile reduction by 2012).

At the time that the chemical weapons treaty came in force, the U.S. stored its chemical weapons at eight U.S. Army installations within the Continental United States (CONUS). The stockpiles were maintained in exclusion zones[18] at the following Department of Army installations, (the percentages shown are reflections of amount by weight):

- Tooele Army Depot (TEAD), Utah (42.3% of total stockpile)

- Pine Bluff Arsenal (PBA), Arkansas (12%)

- Umatilla Depot Activity (UMDA), Oregon (11.6%)

- Pueblo Chemical Depot (PCD), Colorado (9.9%)

- Anniston Army Depot (ANAD), Alabama (7.1%)

- Aberdeen Proving Ground (APG), Maryland (5%)

- Newport Army Ammunition Plant (NAAP), Indiana (3.9%)

- Blue Grass Army Depot (BGAD), Kentucky (1.6%).

The remaining 6.6% was located on Johnston Atoll in the Pacific Ocean.

Stockpiles have been eliminated at Johnston Atoll, Aberdeen, Newport, Umatilla,[19] Pine Bluff,[20] Tooele,[21] and Anniston.[22] The elimination of the Pueblo and Blue Grass stockpiles are scheduled to complete by the Chemical Weapons Convention treaty commitment of Sept. 30, 2023. U.S. Public Law mandates stockpile destruction by Dec. 31, 2023.

According to the U.S. Army Chemical Materials Agency, by January 2012 the United States had destroyed 89.75% of the original stockpile of nearly 31,100 metric tons (34,300 tons) of nerve and mustard agents declared in 1997.[16] The U.S. disposed of the more dangerous modern chemical weapons before starting the destruction of its older mustard gas stockpile which presented additional difficulties due to the poor condition of some of the shells. Of the weapons destroyed up to 2006, 500 tons were mustard gas and the majority were other agents such as VX and sarin (GB) (86% of the latter was destroyed by April 2006).[23] 14,000 metric tons (15,400 tons) of prohibited weapons had been destroyed by June 2007 to meet the Phase III quota and deadline.[24]

The original commitment in Phase III required all countries to have 45 percent of the chemical stockpiles destroyed by April 2004. Anticipating the failure to meet this deadline, the Bush administration in September 2003 requested a new deadline of December 2007 for Phase III and announced a probable need for an extension until April 2012 for Phase IV, total destruction (requests for deadline extensions cannot formally be made until 12 months before the original deadline). This extension procedure spelled out in the treaty has been utilized by other countries, including Russia and the unnamed "state party". Although April 2012 is the latest date allowed by the treaty, the U.S. also noted that this deadline may not be met due to environmental challenges and the U.S. decision to destroy leaking individual chemical shells before bulk storage chemical weapons.[25][26]

The primary remaining chemical weapon storage facilities in the U.S. are Pueblo Chemical Depot in Colorado and Blue Grass Army Depot in Kentucky.[27] These two facilities hold 10.25% of the U.S. 1997 declared stockpile and destruction operations are under the Program Executive Office, Assembled Chemical Weapons Alternatives.[28] Other non-stockpile agents (usually test kits) or old buried munitions are occasionally found and are sometimes destroyed in place. Pueblo and Blue Grass constructed plants to test novel methods of disposal.[29] Chemical stockpile destruction in Colorado was initiated in March 2015 by the Explosive Destruction System located on the Pueblo Chemical Depot. The destruction facility for Pueblo began disposal operations in September 2016, while the destruction facility for Blue Grass began disposal operations in June 2019. Both Pueblo and Blue Grass are scheduled to complete by the Chemical Weapons Convention treaty commitment of Sept. 30, 2023. U.S. Public Law mandates stockpile destruction by Dec. 31, 2023.

In 1988–1990, the destruction of munitions containing BZ, a non-lethal hallucinating agent occurred at Pine Bluff Chemical Activity in Arkansas. Hawthorne Army Depot in Nevada destroyed all M687 chemical artillery shells and 458 metric tons of binary precursor chemicals by July 1999. Operations were completed at Johnston Atoll Chemical Agent Disposal System, where all 640 metric tons of chemical agents were destroyed by 2000, as well as at Edgewood Chemical Activity in Maryland, with 1,472 metric tons of agents destroyed by February 2006. All DF and QL, chemical weapons precursors, were destroyed in 2006 at Pine Bluff. Newport Chemical Depot in Indiana began destruction operations in May, 2005 and completed operations on August 8, 2008, disposing of 1,152 tonnes of agents. Pine Bluff completed destruction of 3,850 tons of weapons on November 12, 2010. Anniston Chemical Activity in Alabama completed disposal on September 22, 2011. Umatilla Chemical Depot in Oregon finished disposal on October 25, 2011. Tooele Chemical Demilitarization Facility at Deseret Chemical Depot in Utah finished disposal on January 21, 2012.[16]

See also

- List of U.S. chemical weapons topics

- M23 chemical mine

- Rocky Mountain Arsenal

- United States and weapons of mass destruction

- Program Executive Office, Assembled Chemical Weapons Alternatives

References

- ^ a b Gross, Daniel A. (Spring 2015). "Chemical Warfare: From the European Battlefield to the American Laboratory". Distillations. 1 (1): 16–23. Retrieved March 20, 2018.

- ^ a b c Hilmas, Corey J., Jeffery K. Smart, and Benjamin A. Hill, “History of Chemical Warfare”, Chapter 2 in Lenhart, Martha K., Editor-in Chief (2008), Medical Aspects of Chemical Warfare, Borden Institute: GPO, pg 40.

- ^ Addison, James Thayer (1919). The story of the First gas regiment. Boston and New York: Houghton Mifflin company. pp. 50, 146, 158, 168. Retrieved 14 April 2017.

- ^ D. Hank Ellison (August 24, 2007). Handbook of Chemical and Biological Warfare Agents, Second Edition. CRC Press. p. 456. ISBN 978-0-8493-1434-6.

- ^ Hershberg, James G. (1993). James B. Conant : Harvard to Hiroshima and the making of the nuclear age. Stanford, Cal.: Stanford University Press. p. 47. ISBN 0-8047-2619-1.

- ^ https://nonproliferation.org/chemical-weapon-munitions-dumped-at-sea/

- ^ "Is Military Research Hazardous To Veterans' Health? Lessons Spanning Half A Century". December 8, 1994. Archived from the original on August 13, 2006. Report for the Committee On Veterans' Affairs

- ^ 007 Incapacitating Agents

- ^ Julian Ryall (10 June 2010). "Did the US wage germ warfare in Korea?". London: Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 2010-06-15.

- ^ "North Korea Persists in 54 year-old Disinformation". US Department of State. 9 Nov 2005. Archived from the original on 2005-11-12. Retrieved 2005-11-12.

- ^ Hilmas, Op. cit., pg 59.

- ^ Biological Weapons Convention

- ^ "45 Percent Chemical Weapons Convention Milestone". Archived from the original on 8 June 2011.

- ^ Broadus, James M., et al. The Oceans and Environmental Security: Shared U.S. and Russian Perspectives, (Google Books), p. 103, Island Press, 1994, (ISBN 1559632356), accessed October 25, 2008.

- ^ "Department of Defense Report Chemical Demilitarization Program Semi-Annual Report to Congress (PDF)" (PDF). Program Executive Office, Assembled Chemical Weapons Alternatives. May 2009.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ a b c Army Agency Completes Mission to Destroy Chemical Weapons Archived 2012-09-15 at the Wayback Machine, USCMA, January 21, 2012

- ^ "Assembled Chemical Weapons Alternatives Program Legislation Fact Sheet (PDF)" (PDF). Program Executive Office, Assembled Chemical Weapons Alternatives. September 1, 2020.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ "Public Law 99-145 Attachment E" (PDF).

- ^ "Chemical weapon stockpile destroyed at Oregon's Umatilla site". Latimesblogs.latimes.com. 2011-10-25. Retrieved 2013-09-05.

- ^ Arndt, Richard (November 15, 2010). "U.S. Army Completes Chemical Stockpile Destruction at Pine Bluff Chemical Agent Disposal Facility". U.S. Army Chemical Materials Agency. Retrieved June 27, 2016.

- ^ "Army Agency Completes Mission to Destroy Chemical Weapons". www.cma.army.mil. U.S. Army Chemical Materials Agency. Retrieved January 21, 2012.

- ^ Abrams, Michael (September 29, 2011). "ANCDF completes chemical munitions mission". www.army.mil. Retrieved June 27, 2016.

- ^ "United States Seeks Extension for Chemical Weapons Destruction - US Department of State". Archived from the original on 2008-05-18. Retrieved 2013-09-11.

- ^ U.S. Army Chemical Materials Agency, http://www.cma.army.mil/ Archived 2006-04-27 at the Wayback Machine, accessed September 28, 2007

- ^ Chemical Weapons Convention

- ^ "Statement by Ambassador Eric M. Javits United States Delegation to the Eighth Conference of States Parties of the Organization for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons 20 October 2003" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on September 10, 2008. Retrieved September 11, 2013.

- ^ Chemical Weapons United States

- ^ "Closing U.S. Chemical Warfare Agent Disposal Facilities". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2013-06-25.

- ^ "ACWA Program Timeline". Program Executive Office, Assembled Chemical Weapons Alternatives.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link)