New York World Building

| New York World Building | |

|---|---|

| |

| |

| Alternative names |

|

| General information | |

| Status | Demolished |

| Type | Commercial offices |

| Architectural style | Renaissance Revival |

| Location | 53–63 Park Row New York City, US |

| Coordinates | 40°42′43″N 74°00′19″W / 40.7120°N 74.0053°W |

| Construction started | October 10, 1889 |

| Completed | December 10, 1890 |

| Renovated | 1907–1908 |

| Demolished | 1955 |

| Height | |

| Architectural | 309 ft (94 m) |

| Antenna spire | 350 ft (110 m) |

| Roof | 191 ft (58 m) |

| Technical details | |

| Floor count | 18 |

| Design and construction | |

| Architect(s) | George B. Post |

| Renovating team | |

| Architect(s) | Horace Trumbauer |

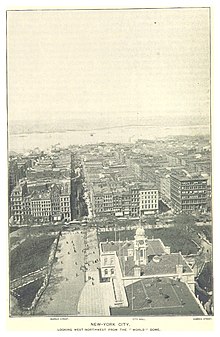

The New York World Building (also the Pulitzer Building) was a building in the Civic Center of Manhattan in New York City, along Park Row between Frankfort Street and the Brooklyn Bridge. Part of the former "Newspaper Row", it was designed by George B. Post in the Renaissance Revival style, serving as the headquarters of the New York World after its completion in 1890. The New York World Building was the tallest building in New York City upon completion, becoming the first to overtop Trinity Church, and was by some accounts the world's tallest building.

The World Building contained a facade made of sandstone, brick, terracotta, and masonry. Its interior structure included brick interior walls, concrete floors, and an internal superstructure made of iron. There were twelve full stories, two basements, and a six-story dome at the top of the building. The pinnacle above the dome reached 350 feet (110 m). When the building was in use, the World primarily used the dome, ground floor, and basements, while the other stories were rented to tenants. The World Building's design generally received mixed reviews, with criticism focusing mostly on its immense scale.

The World's owner Joseph Pulitzer started planning for a new World headquarters in the late 1880s, and hired Post to design the building as a result of an architectural design competition. Construction took place from October 1889 to December 1890. Following the World's subsequent success, Horace Trumbauer designed a thirteen-story annex for the World Building, which was erected between 1907 and 1908. When the World closed in 1931, the building was used as headquarters of The Journal of Commerce. The World Building was demolished between 1955 and 1956 to make room for an expanded entrance ramp to the Brooklyn Bridge. A large stained glass window and the building's cornerstone were preserved by the Columbia University School of Journalism.

Site

The New York World Building was at 53–63 Park Row, at the northeast corner with Frankfort Street, in the Civic Center of Manhattan, across from New York City Hall. The building initially occupied a roughly parallelogram-shaped land lot with frontage of 115 feet (35 m) on Park Row to the northwest and 136 feet (41 m) on Frankfort Street to the south. It abutted the Brooklyn Bridge to the north and other buildings to the east; the lot originally had a cut-out on the northeastern corner so that the Brooklyn Bridge side was shorter than the Frankfort Street side. Immediately to the south of the site was the New York Tribune Building.[1][2][3] Frankfort Street sloped downward away from Park Row so that while the basement was one level below Park Row, it was only a few steps below grade at the eastern end of the Frankfort Street frontage.[1][3]

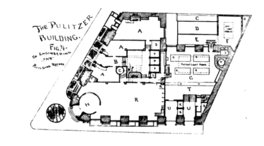

After an annex eastward to North William Street was completed in 1908, the building took up the entire city block and had a frontage of 85 feet (26 m) along North William Street.[4][5] The expanded building had 237 feet (72 m) of frontage on Frankfort Street. The annex covered a lot of 7,500 square feet (700 m2), giving the building a total lot area of 18,496 square feet (1,718.3 m2).[5]

Prior to the World Building's development, the building was the site of French's Hotel.[6][7] The hotel had been developed after the lots were acquired by one John Simpson in 1848.[8] The World's owner and the building's developer, Joseph Pulitzer, had been thrown out of the same hotel during the American Civil War; at the time, he was a recent Hungarian immigrant who had volunteered to serve in the Union Army's cavalry.[9]

Architecture

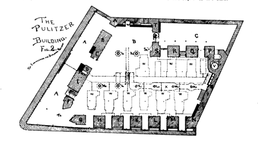

The original portion of the New York World Building was completed in 1890 and designed by George B. Post in the Renaissance Revival style with some Venetian Renaissance detail. The World Building was also known as the Pulitzer Building, after Joseph Pulitzer.[10][11] Multiple contractors provided the material for the structure.[12] The World Building consisted of a "tower" with twelve full stories, topped by a six-story dome. This count excluded a mezzanine above the first story but included a viewing gallery in the dome. Including the mezzanine and a penthouse above the twelfth story of the tower, the latter of which was at the same height as the dome's first level, the tower had fourteen stories.[13]

When the building opened in 1890, the World Building's dome had a height of 310 feet (94 m) and a spire of 350 feet (110 m), though this calculation was measured from the eastern end of the Frankfort Street frontage, rather than from the main frontage on Park Row.[14][15][16] The flat roof was 191 feet (58 m) above sidewalk level.[3][15] The World Building was New York City's tallest building when opened, becoming the first to rise higher than Trinity Church's 284-foot (87 m) spire.[17] By some accounts, it was also the world's tallest building, when the spire was counted.[18][19]

The actual number of stories in the World Building was disputed.[17] The World described the building as having 26 stories, counting the tower as fourteen stories and including two subsurface levels, three mezzanines, and an observatory over the dome.[3][15][16] However, scholars described the building as having only 16 or 18 stories, excluding mezzanines, below-ground levels, and levels that could not be fully occupied.[14][17] Contemporary media characterized the structure as an 18-story building,[10] while Emporis and SkyscraperPage, two websites that collect data on buildings, listed the building as having 20 stories.[14][20]

A thirteen-story annex to William Street, completed in 1908, was designed by Horace Trumbauer in the same style as Post's design.[21] This annex replaced a two-story addition to the original World Building on Frankfort Street.[3]

Facade

Park Row

The main elevation on Park Row was clad with red sandstone below the tenth story, and buff brick and terracotta above. At the base, the columns were made of red granite, while the spandrel panels between each story were gray granite.[3][22][11] The Park Row elevation contained five bays, of which the three center bays formed a slightly projecting pavilion with a triple-height entrance arch at the base. There were two small circular windows in the spandrels of the arch, and a frieze with the words pulitzer building and a cornice above the arch.[23][24] On the 3rd story, the three central windows were flanked by four ornamental bronze female torch-bearers carved by Karl Bitter, which represented the arts.[22][25]

Pedestals flanked the center bays on the 4th story. The 5th through 10th stories of the center bays were divided horizontally into three sets of double-height arches, each supported by four pairs of columns. At the 11th story, four pairs of square piers divided each bay.[23][26] Four 16-foot-tall (4.9 m) black copper caryatids by Bitter, representing human races, flanked the 12th-story windows.[22][26] A cornice and balustrade ran above the 12th story, with a pediment above the center bays, as well as a terracotta panel containing the carved monogram j. p. and the date "1889".[26] The outer bays of the Park Row elevation had double-height arched windows above the mezzanine and 3rd story, and square windows above. All of the bays had arched windows on the 12th story.[23][26]

Other facades

Between the Park Row and Frankfort Street elevations was a rounded corner that spanned from the first to tenth stories. The corner entrance contained a double-height arch flanked by female figures depicting justice and truth. As in the center bays on Park Row, there were three sets of double-height arches between the fifth and tenth stories. A balustrade ran above the tenth story of the rounded corner, and the 11th and 12th stories were recessed from that corner, with a convex wall running perpendicularly from both Park Row and Frankfort Street.[23][26]

On Frankfort Street, the facade was clad with red sandstone below the 3rd story, and buff brick and terracotta above.[3][27] The North William Street facade was similar to that of the original building but had granite facing on the 1st story and brick with terracotta above.[4]

Features

There were eighteen lifts in the building, including passenger and freight elevators.[10][28] The elevators were made of iron and encased in glazed brick walls. Four hydraulic elevators served passengers; three were for the use of the office tenants below the 12th floor, while the fourth was a circular elevator that ran to the dome and was used exclusively by the World's staff.[3][10][29] Two additional elevators were used by other employees. Nine other lifts were used to transport materials: one each for stereotype plates, rolls of paper, coal, copy, and restaurant use, and four to carry the stereotype plates and printed papers.[29]

The building was heated by a steam system throughout and contained 3,500 electric lights at its opening.[3][30] The three boilers in the subbasement could generate a combined 750 horsepower (560 kW).[3][31] In addition, there was a pneumatic tube system to transport items from the dome to the basement.[3][30] A water storage tank with a capacity of 25,000 U.S. gallons (95,000 L; 21,000 imp gal) was situated in the cellar, and fed water to a smaller 7,000-U.S.-gallon (26,000 L; 5,800 imp gal) tank at the rear of the roof.[30]

There were 142,864 square feet (13,272.5 m2) of available floor space upon the building's opening,[3][32] which was "practically doubled" with the completion in 1908 of the building's William Street annex.[33] The hallways were tiled, while the entrances were finished in marble. The floors of the World Building's offices were made of Georgia pine upon a concrete base. Ash was used for woodwork finish, except in the publication office, where mahogany was used.[3][32] The building contained a total of 250 units, of which 149 were rented to tenants and 79 were used by the World's staff.[10][13]

Structural features

The foundation of the World Building was excavated to a depth of 35 feet (11 m), just above the water level; the underlying layer of bedrock was around 100 feet (30 m) deep. The foundation consisted of a "mat" of concrete, overlaid by a series of large stones that formed inverted arches between them. The brick and concrete foundation piers rested upon these arches, which in turn descended to the underlying gravel bed.[3][10][34] Such construction was common among the city's large 19th-century buildings but had a tendency to break apart.[35] Hard brick was used for the foundation walls up to the basement story, above which large granite blocks were placed in the wall.[32] The foundation used 21,000 cubic yards (16,000 m3) of sand, plaster, lime, and cement.[32]

The World Building contained a hybrid cage-frame structure whose exterior walls were partially load-bearing.[14][35] The exterior walls' thicknesses had been prescribed by city building codes of the time.[35] They were generally 88 inches (2,200 mm) thick at the base, with the thickest wall being 144 inches (3,700 mm) thick at the base, but tapered to 24 inches (610 mm) just below the dome.[10][32][36] The exterior wall sections on Park Row and Frankfort Street were so large because they were not part of a single connected wall but instead consisted of several piers, which had to be thicker than continuous walls per city codes.[35] Inside was a superstructure of wrought iron columns supporting steel girders, which collectively weighed over 2,000,000 pounds (910,000 kg). The columns tapered upward, from 28 feet (8.5 m) at the base to 8 inches (200 mm) at the top. Flat arches, made of hollow concrete blocks, were placed between the girders.[10][16]

The dome's frame was designed as if it were a separate structure.[3][10] The dome measured 52 feet (16 m) across at its base and measured 109 feet (33 m) from the main roof to the lantern. The dome consisted of a wrought-iron framing with double-diagonal bracing between every other pair of columns. The ribs supporting the dome were placed on top of iron columns that descended directly to the building's foundation without intersecting with the rest of the superstructure.[10][37] The exterior of the dome was made of copper and contained cornices above the first and third stories of the dome. The fourth and fifth dome stories were divided by the ribs into twelve sections with small lunette windows on each story.[37] At the top of the dome was a lantern surrounded by an observatory.[37][38] Visitors could pay five cents to travel to the observatory.[38]

Interior

The building had two subsurface levels. The basement below the street had a ceiling 10 feet (3.0 m) high, and protruded 6 feet (1.8 m) under the roadway on Park Row, but had an entrance at Frankfort Street due to the slope of the street. The basement contained the machinery for the building's elevator and plumbing lines, a stereotype room, employee rooms, and a passageway to two elevators. The subbasement, or cellar, had ceilings 16 feet (4.9 m) high for the most part, with the boiler room containing a ceiling 18 feet (5.5 m) high. It extended under the sidewalk on Frankfort Street and protruded the same distance under Park Row as the first basement. The cellar contained the elevator and house pumps, engine room, the printing presses, and a visitors' gallery.[10][39][40]

The ground floor contained the main entrance, as well as the publication office, private offices, counting room, and three stores. The main entrance from Park Row led to a large circular rotunda running eastward, containing floors and walls decorated in white and pink marbles, and a ceiling vault measuring 19.5 feet (5.9 m) wide by 17 feet (5.2 m) high.[3][41] After the annex was completed in 1908, the ground-floor lobby extended 200 feet (61 m) between Park Row and North William Street.[33] The World's cashier's and bookkeeper's offices occupied the mezzanine over the 1st floor.[3][42] The original two-story annex on Frankfort Street contained a newspaper-delivery department on its lower story, and bookkeepers' departments on its upper story.[39]

The mezzanine through 10th stories were used as offices.[3][10][33] Advertisements indicated that there were a 75-seat "Assembly Hall" and 350-seat "Assembly Room" available for rent.[43] The 11th floor originally contained the editorial department of the Evening World,[44] and a two-bedroom apartment used during "special occasions".[10][45] The 12th story was used as a composing room and contained galleries for proofreaders and visitors. There was also a night editors' department on the 12th floor.[39][44] Above it was a roof from which the dome rose.[39] The roof was slightly graded and contained a layer of concrete and five layers of felt-and-asphalt above steel beams.[27] A penthouse on the roof, located at the same height at the first story of the dome, contained the offices of the managing and Sunday editor, the art and photo-engraving departments, and an employee restaurant.[46]

The six-story dome was used exclusively by editorial offices, Pulitzer's private office, and the paper's library.[10][39][46] The first level originally housed the city editors' department and had offices for over one hundred people.[46][47] The main ceiling of the first dome story was 19.5 feet (5.9 m) tall, but an overhanging gallery ran around the circumference of the dome, 9.5 feet (2.9 m) above the fifteenth floor.[47] Pulitzer's office was on the second level of the dome and featured frescoes on the ceiling, embossed leather walls, and three large windows.[9][48] The second dome story also contained the vice president's apartment, editorial writers' offices, and Council Chamber offices.[48] The second level had a ceiling of 20.5 feet (6.2 m) while subsequent dome stories had slightly shorter ceilings.[47] The third level contained offices for clerical assistants, the chief artist and cartoonist, and other staff, while the fourth level contained the file room and obituary departments. The fifth level was used as an observatory and storeroom.[49] By 1908, the art department and the World's library were located in the 11th story.[33]

History

Starting in the early 19th century and continuing through the 1920s, the surrounding area grew into the city's "Newspaper Row". Several newspaper headquarters were built on Park Row just west of Nassau Street, including the Potter Building, the Park Row Building, the New York Times Building, and the New York Tribune Building.[50][51] The New York World and other newspapers would be among the first to construct early skyscrapers for their headquarters.[52] Meanwhile, printing was centered around Beekman Street, two blocks south of the World Building.[50][53]

The New York World was established in 1860, and initially occupied a structure two blocks south at 37 Park Row, later the Potter Building's site.[54][55] The original World building burned down in 1882,[56][57] killing six people[58] and causing more than $400,000 in damage (equivalent to $13 million in 2023[a]).[56][57] The World was subsequently housed at 32 Park Row. Joseph Pulitzer purchased the World in 1883, and the paper's circulation grew tenfold in the following six years, so that 32 Park Row became too small for the paper's operations.[1][59]

Planning and construction

In June 1887, Pulitzer purchased land at 11 Park Row and 5–11 Ann Street at a cost of $140,000.[60][61] The lot was directly across from the headquarters of the New York Herald at the intersection of Park Row, Broadway, and Ann Street.[1][b] Pulitzer planned to erect a tall headquarters on the site,[1] but Herald owner James Gordon Bennett Jr. bought the corner of Park Row and Ann Street, precluding Pulitzer from acquiring enough land for a skyscraper.[63] In April 1888, Pulitzer bought the site of French's Hotel at Frankfort Street, three blocks north of Ann Street;[6][7] the hotel site was considered the only one in the neighborhood that was both large enough and affordable for Pulitzer.[63] Pulitzer's estate retained control of the lots at 11 Park Row and Ann Street,[64] but did not develop them.[32] Demolition of the hotel commenced in July 1888.[8]

Numerous professional advisors, including Richard Morris Hunt, were hired to judge the architectural design competition through which the architect was to be selected.[65] According to the Real Estate Record and Guide, "about half a dozen well-known architects" had submitted plans by August 1888, when French's Hotel was nearly completely demolished.[66] By October 1888, George B. Post had been selected as the building's architect.[34][67] Supposedly, Post had called Pulitzer after submitting his plans, and he had designed the building to "annex" over the Brooklyn Bridge approach. He also apparently bet $20,000 against Pulitzer's $10,000 that the project would stay within the $1 million budget that Pulitzer had outlined, even though the building apparently ended up costing $2 million.[1][59] Pulitzer dictated several aspects of the design, including the triple-height main entrance arch, the dome, and the rounded corner at Park Row and Frankfort Street.[22][68] Post expressed particular concern about the entrance arch, which entailed removing "valuable renting space" around the arch and initially thought the entrance "wellnigh an impossibility".[22][24]

The foundations for French's Hotel were not completely removed until early June 1889,[69] and so foundation work for the World Building began on June 20, 1889.[34] Although the excavations extended under the surrounding sidewalks and even under part of Park Row, traffic was barely disrupted, mostly because of the inclusion of temporary bridges for pedestrians and for materials storage.[3][70] The cornerstone of the New York World Building was laid at a groundbreaking ceremony held on October 10, 1889.[34][71][72] Work progressed quickly; three months after the groundbreaking, the steel structure had reached nine stories and the masonry had reached six stories.[70] Despite a labor strike among the builders in April 1890[73] many offices were ready for tenants by that October.[70] The building was formally completed on December 10, 1890, with a luncheon, speeches from several politicians, and a fireworks display from the dome.[74][75]

World usage

The World prospered through the 1890s and the early 20th century.[21] At the time of its opening, the World was outselling its competitors, with a daily circulation greater than the Herald, Tribune, Sun, and Times individually, and greater than the latter three papers combined.[76] In its early years, the World Building's dome was used for various purposes: its lantern was used to display results for the 1894 United States elections,[77] and a projector on the dome was used to display messages in the night sky.[78] During a heat wave in 1900, the World hired a "noted rainmaker" to detonate two dozen "rain bombs" from the building's dome.[79]

By 1906, Horace Trumbauer was hired to design a thirteen-story annex for the building extending eastward to North William Street.[80] Trumbauer filed plans for the expansion in January 1907, while D. C. Weeks & Son were hired as contractors.[4][81] Work on the extension began the next months.[5] The expanded structure and the World's 25th anniversary were celebrated with a ceremony on May 9, 1908, with a fireworks display and several speeches.[82][83] A large stained glass window by Otto Heinigke, combining the Statue of Liberty and the New York World banner, was installed over the North William Street entrance to the annex.[84][85] The stained glass window alluded to how the World had helped raise funds for the statue's pedestal from the public in 1883, before the statue's construction.[86]

Despite the expansion of the building, the World declined in stature during the 1910s and 1920s.[21] Several notable events took place at the building during this time. In 1911, American Civil War spy Pryce Lewis killed himself by jumping off the building's dome, having been denied a government pension.[87][88] After the World's exposé of the Ku Klux Klan was published in September 1921, the Ku Klux Klan threatened to destroy the building with a bomb, prompting an armed guard of police and Department of Justice employees to be stationed outside of the building.[89] The next year, the facade of the World Building was used to display scores from the 1922 World Series.[90] There were also some minor fires, including one in 1919,[91] and another in 1924 that slightly damaged the World's presses.[92] Overall, the World was not prospering financially, and it shuttered in 1931.[21][93]

Later use and demolition

In 1933, The Journal of Commerce leased four floors in the World Building to use as its headquarters.[94][95] Another long-term tenant, Negro league baseball executive Nat Strong, occupied the building from 1900 until his death in 1935.[96] Strong apparently owned the building for some time after the World had gone defunct.[97] By 1936, there were proposals to demolish the World Building as part of a plan to widen the Manhattan approach to the Brooklyn Bridge.[98]

The Central Hanover Bank and Trust Company, acting as trustee of Pulitzer's estate, sold the building to Samuel B. Shankman in 1941 for $50,000 plus taxes.[99][100] Shankman planned to renovate the structure and hold it as an investment.[99][101] At the time of the sale, the building was valued at $2.375 million, but the tax assessment was reduced to $2.105 million shortly afterward.[102] In 1942, the facade was thoroughly cleaned for the first time since the building's completion.[103] The next year, the building became the headquarters of Local Draft Board 1, which at the time was described as the "largest in the United States" of its kind.[104] Socony-Mobil leased 6,000 square feet (560 m2) in the World Building in 1946, using the space as a staff-training center with a 180-seat auditorium, a projecting room, and a publicly accessible exhibit room.[105]

Robert F. Wagner Jr., the Manhattan borough president, proposed redesigning the streets around the Manhattan entrance to the Brooklyn Bridge in 1950,[106] and the New York City Planning Commission approved an associated change to the zoning map that August.[107] Details of the plan were released in November 1952.[108] A ramp between the Brooklyn Bridge and southbound Park Row, as well as two ramps carrying northbound Park Row both onto and around the bridge, were to be constructed on the World Building's site.[109] The Planning Commission officially approved Wagner's plan in January 1953,[110] but the New York City Board of Estimate temporarily delayed the building's demolition when it laid over the street-redesign plan.[111] The next month, the Board of Estimate also approved Wagner's plan. The Journal of Commerce, by then the last remaining newspaper to publish from Park Row, moved out of the World Building the day after the Board of Estimate's approval.[112] The Board of Estimate moved to acquire the World Building's land in June 1953,[113] and borough president Hulan Jack signed demolition contracts for the building the next year.[114]

In December 1954, during a renovation of City Hall, the office of now-mayor Wagner temporarily moved from City Hall to the World Building.[115] Demolition work on the World Building started in mid-March 1955, and the last commercial tenants were required to leave by April 1. The mayor's office planned to stay in the building until May 1, so mayoral aides arranged for demolition contractors to conduct only minor facade removals until then. In preparation for the construction of the new ramps, the demolition contractors would also strengthen the World Building's foundations.[116] The mayor's office, the last tenant of the World Building, moved back to City Hall on May 13, 1955.[117] The site was mostly cleared by the beginning of 1956,[118] and work on the new Brooklyn Bridge approaches began later that year.[119]

Legacy

The World Building received mixed reviews upon its completion. The World wrote of its headquarters: "There is a sermon in these stones: a significant moral in this architectural glory."[59] The Real Estate Record and Guide wrote that the building was too tall for its lot, especially considering that it could not be viewed in full from the narrow Frankfort Street, and that "there have been no pains at all taken to keep the building down", with a particularly sharp dissonance between the tower and dome.[21][2] Another reviewer wrote that "The World building is a monstrosity in varicolored brick and stone".[21] The Skyscraper Museum stated that "The distinctive dome provided a visual identity for the newspaper", and that the lantern on the dome was used at night as a beacon for ships.[38]

The building's Heinigke stained glass window was bought by a group headed by a Columbia University journalism professor. In 1954, when the building's demolition was announced, it was brought to Room 305 of the Columbia University School of Journalism.[86][120] Columbia was also set to receive the cornerstone, and demolition contractors spent more than a year looking for it.[118] The cornerstone was finally discovered in February 1956,[121] using a Geiger counter to detect radiation from the cornerstone.[122] Columbia received the cornerstone that month.[123][124] The box included publications from 1889; Pulitzer family photographs; gold and silver coins; a medallion celebrating the World's having reached a circulation from 250,000; and dedication speeches, recorded in wax phonograph cylinders.[70][123][124]

The World Building, as an early New York City icon, appeared in several works of media. It was mentioned in the novel Manhattan Transfer by John Dos Passos.[125] The building was also featured on the cover of the World Almanac from 1890 to 1934.[38]

References

Notes

- ^ 1634–1699: McCusker, J. J. (1997). How Much Is That in Real Money? A Historical Price Index for Use as a Deflator of Money Values in the Economy of the United States: Addenda et Corrigenda (PDF). American Antiquarian Society. 1700–1799: McCusker, J. J. (1992). How Much Is That in Real Money? A Historical Price Index for Use as a Deflator of Money Values in the Economy of the United States (PDF). American Antiquarian Society. 1800–present: Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis. "Consumer Price Index (estimate) 1800–". Retrieved February 29, 2024.

- ^ The Herald building was later replaced by the 1898 St. Paul Building.[62]

Citations

- ^ a b c d e f Landau & Condit 1996, p. 197.

- ^ a b "The New World Building". The Real Estate Record: Real Estate Record and Builders' Guide. 45 (1161): 879. June 14, 1890. Archived from the original on March 31, 2022. Retrieved September 28, 2020 – via columbia.edu.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s Engineering and Building Record 1890, p. 342.

- ^ a b c "Pulitzer Building to be Extended". The New York Times. January 25, 1907. p. 6. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on April 24, 2022. Retrieved September 28, 2020 – via newspapers.com

.

.

- ^ a b c "Telegraphic Briefs". Western Herald. February 20, 1907. p. 6. Archived from the original on April 24, 2022. Retrieved September 28, 2020 – via newspapers.com

.

.

- ^ a b "A New 'World' Building". New York Evening World. April 11, 1888. p. 2. Archived from the original on April 24, 2022. Retrieved September 25, 2020 – via newspapers.com

.

.

- ^ a b "The Great Investments of the Past Year". The Real Estate Record: Real Estate Record and Builders' Guide. 41 (1048): 464. April 14, 1888. Archived from the original on April 24, 2022. Retrieved September 28, 2020 – via columbia.edu.

- ^ a b Burr Printing House 1890, p. 8.

- ^ a b Burrows, Edwin G. and Wallace, Mike (1999). Gotham: A History of New York City to 1898. New York: Oxford University Press. p. 1051. ISBN 0-195-11634-8.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n Landau & Condit 1996, p. 199.

- ^ a b Burr Printing House 1890, p. 16.

- ^ Engineering and Building Record 1890, p. 343.

- ^ a b Burr Printing House 1890, pp. 47–48.

- ^ a b c d "World Building". Emporis. Archived from the original on February 12, 2007. Retrieved September 28, 2020.

- ^ a b c Landau & Condit 1996, pp. 197–199.

- ^ a b c Burr Printing House 1890, p. 6.

- ^ a b c "World Building". The Skyscraper Museum. Archived from the original on June 12, 2020. Retrieved September 28, 2020.

- ^ McKinley, Jesse (November 5, 1995). "F.y.i.". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on March 28, 2019. Retrieved October 5, 2020.

- ^ "World Building – The Skyscraper Center". The Skyscraper Center. April 7, 2016. Archived from the original on August 10, 2019. Retrieved October 5, 2020.

- ^ "New York World Building, New York City". SkyscraperPage. Archived from the original on June 12, 2020. Retrieved September 28, 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f Landau & Condit 1996, p. 201.

- ^ a b c d e Landau & Condit 1996, p. 200.

- ^ a b c d Landau & Condit 1996, p. 198.

- ^ a b Burr Printing House 1890, p. 17.

- ^ Burr Printing House 1890, pp. 17–18.

- ^ a b c d e Burr Printing House 1890, p. 18.

- ^ a b Burr Printing House 1890, p. 19.

- ^ Burr Printing House 1890, p. 44.

- ^ a b Burr Printing House 1890, p. 45.

- ^ a b c Burr Printing House 1890, p. 46.

- ^ Burr Printing House 1890, p. 41.

- ^ a b c d e f Burr Printing House 1890, p. 7.

- ^ a b c d "Joy at 'The World': Anniversary Observed". New-York Tribune. May 10, 1908. p. 3. Archived from the original on April 24, 2022. Retrieved September 28, 2020 – via newspapers.com

.

.

- ^ a b c d Burr Printing House 1890, p. 10.

- ^ a b c d Willis, Carol. "The Skyscraper Museum: News Paper Spires Walkthrough; Pulitzer's World Building". The Skyscraper Museum. Archived from the original on February 16, 2022. Retrieved September 26, 2020.

- ^ Engineering and Building Record 1890, p. 358.

- ^ a b c Burr Printing House 1890, p. 20.

- ^ a b c d Willis, Carol. "The Skyscraper Museum: Times Square, 1984: The Postmodern Moment Walkthrough". The Skyscraper Museum. Retrieved September 28, 2020.

- ^ a b c d e Engineering and Building Record 1890, pp. 342–343.

- ^ Burr Printing House 1890, pp. 36, 38, 40.

- ^ Burr Printing House 1890, pp. 21, 23–24.

- ^ Burr Printing House 1890, pp. 24, 26.

- ^ "Out-of-Town Business Men". New York Evening World. September 23, 1913. p. 10. Archived from the original on April 24, 2022. Retrieved September 28, 2020 – via newspapers.com

.

.

- ^ a b Burr Printing House 1890, pp. 26–27.

- ^ Burr Printing House 1890, p. 34.

- ^ a b c Burr Printing House 1890, pp. 29–30.

- ^ a b c Engineering and Building Record 1890, p. 360.

- ^ a b Burr Printing House 1890, pp. 30, 32.

- ^ Burr Printing House 1890, p. 32.

- ^ a b "(Former) New York Times Building" (PDF). New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. March 16, 1999. p. 2. Archived (PDF) from the original on November 4, 2021. Retrieved September 20, 2020.

- ^ Jackson, Kenneth T., ed. (2010). The Encyclopedia of New York City (2nd ed.). New Haven: Yale University Press. p. 893. ISBN 978-0-300-11465-2.

- ^ "Fulton–Nassau Historic District" (PDF). National Register of Historic Places, National Park Service. September 7, 2005. p. 27. Archived (PDF) from the original on February 19, 2021. Retrieved September 20, 2020.

- ^ "Paternoster Row of New-York". New York Mirror. 13: 363. May 14, 1836. Archived from the original on July 15, 2020. Retrieved September 28, 2020.

- ^ Landmarks Preservation Commission 1996, p. 3.

- ^ Potter, Blanche (1923). More Memories: Orlando Bronson Potter and Frederick Potter. J.J. Little & Ives Co. p. 40.

- ^ a b "Flames in a Death-Trap; the Potter Building Completely Destroyed. Loss of at Least Five Lives and $700,000 in Property". The New York Times. February 1, 1882. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on March 24, 2020. Retrieved March 24, 2020.

- ^ a b "That Fire" (PDF). The Real Estate Record: Real Estate Record and Builders' Guide. 29 (725): 95. February 4, 1882. Archived (PDF) from the original on March 24, 2020. Retrieved September 28, 2020 – via columbia.edu.

- ^ "No More Bodies Found.; the Work of Excavation in the Ruins of the Potter Building". The New York Times. February 6, 1882. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on March 24, 2020. Retrieved March 24, 2020.

- ^ a b c Willis, Carol. "The Skyscraper Museum: News Paper Spires Walkthrough; World Building". The Skyscraper Museum. Archived from the original on February 16, 2022. Retrieved September 25, 2020.

- ^ "The Great Investments of the Past Year". The Real Estate Record: Real Estate Record and Builders' Guide. 39 (1003): 774. June 4, 1887. Archived from the original on April 24, 2022. Retrieved September 28, 2020 – via columbia.edu.

- ^ "Joe Pulitzer's 'Hell'". New York Sun. April 29, 1888. p. 1. Archived from the original on April 24, 2022. Retrieved September 25, 2020 – via newspapers.com

.

.

- ^ "Must Be Quickly Razed; Seventy Days for Destruction of the Old Herald Building". The New York Times. May 1, 1895. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on April 24, 2022. Retrieved August 9, 2020.

- ^ a b "Frankfort Street Memories". Democrat and Chronicle. October 12, 1889. p. 8. Archived from the original on April 24, 2022. Retrieved September 25, 2020 – via newspapers.com

.

.

- ^ "$1,000,000 Park Row Lease; Pulitzer Estate Leases First Site Picked for World Building". The New York Times. February 12, 1921. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on April 24, 2022. Retrieved September 25, 2020.

- ^ Landau & Condit 1996, p. 421.

- ^ "Out Among the Builders". The Real Estate Record: Real Estate Record and Builders' Guide. 42 (1065): 999. August 11, 1888 – via columbia.edu.

- ^ "Out Among the Builders". The Real Estate Record: Real Estate Record and Builders' Guide. 42 (1074): 1225. October 13, 1888. Archived from the original on March 24, 2022. Retrieved September 28, 2020 – via columbia.edu.

- ^ Burr Printing House 1890, pp. 8, 10.

- ^ "Out Among the Builders". The Real Estate Record: Real Estate Record and Builders' Guide. 43 (1107): 768. June 1, 1889. Archived from the original on March 30, 2022. Retrieved September 28, 2020 – via columbia.edu.

- ^ a b c d Burr Printing House 1890, p. 12.

- ^ "A New Newspaper Building". The New York Times. October 11, 1889. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved September 24, 2020.

- ^ "'It is Well Done.': Corner-stone of Pulitzer Building Laid. Many Eloquent Tongues Charm the World's Admirers. Editor's Four-year-old Son Wields the Trowel". Boston Daily Globe. October 11, 1889. p. 2. Retrieved September 25, 2020 – via ProQuest.

- ^ "Delegates Order a Strike.; Trouble Caused for Contractors in Several Buildings". The New York Times. April 12, 1890. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved September 24, 2020.

- ^ "New Home of the World: Pulitzer Building Formally Opened. Luncheon for Thousands—a Flash Light Photograph. Speeches by Gov. Hill, Mayor Grant, Col. Taylor and Others". Boston Daily Globe. December 11, 1890. p. 6. Retrieved September 25, 2020 – via ProQuest.

- ^ "In the New Home". St. Louis Post-Dispatch. December 11, 1890. p. 4. Retrieved September 28, 2020 – via newspapers.com

.

.

- ^ Tichi, Cecelia (2018). What Would Mrs. Astor Do?: The Essential Guide to the Manners and Mores of the Gilded Age. Washington Mews. NYU Press. p. 252. ISBN 978-1-4798-6854-4. Retrieved September 28, 2020.

- ^ "Watch the Dome for the Results". New York Evening World. November 6, 1894. p. 1. Retrieved September 28, 2020 – via newspapers.com

.

.

- ^ "Signs in the Sky". New York Evening World. January 7, 1894. p. 4. Retrieved September 28, 2020 – via newspapers.com

.

.

- ^ "Wooing Rain from Clouds with Bombs". New York Evening World. July 18, 1900. p. 1. Retrieved September 28, 2020 – via newspapers.com

.

.

- ^ "Larger World Building Planned". New-York Tribune. October 21, 1906. p. 14. Retrieved September 28, 2020 – via newspapers.com

.

.

- ^ "Weeks & Son to Erect the World Building Annex". The Real Estate Record: Real Estate Record and Builders' Guide. 79 (2028): 228. January 26, 1907 – via columbia.edu.

- ^ "World Celebrates a 25th Anniversary; Its Remodeled Home Dedicated at Celebration of Mr. Pulitzer's Quarter Century Control". The New York Times. May 10, 1908. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved September 24, 2020.

- ^ "New York World's 25th Anniversary". Brooklyn Daily Eagle. May 10, 1908. p. 8. Retrieved September 28, 2020 – via newspapers.com

.

.

- ^ Russell, John (January 14, 1983). "Stained Glass Casts Its Glow Over the City". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on December 18, 2015. Retrieved September 28, 2020.

- ^ "Joseph Pulitzer and The World". Columbia University Libraries Online Exhibitions. Archived from the original on July 1, 2020. Retrieved September 28, 2020.

- ^ a b "Statue of Liberty Window to Move". Democrat and Chronicle. March 10, 1954. p. 6. Archived from the original on April 24, 2022. Retrieved September 28, 2020 – via newspapers.com

.

.

- ^ "Famous Federal Spy Jumped From the Dome When Denied a Pension". New York Evening World. December 9, 1911. pp. 1, 2 – via newspapers.com

.

.

- ^ "World Dome Suicide a Famous War Spy; He Was Pryce Lewis, Whose Work Gave the Union Army Its First Real Victory". The New York Times. December 10, 1911. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on April 24, 2022. Retrieved September 28, 2020.

- ^ "Guard for World Building; Police Watch for Ku Klux Bomb After Threat of Vengeance". The New York Times. September 9, 1921. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved September 25, 2020.

- ^ "Fans, See Each Play in World's Series On The Evening World's Scoreboard". New York Evening World. October 3, 1922. p. 3. Retrieved September 28, 2020 – via newspapers.com

.

.

- ^ "Blaze In Pulitzer Building". The New York Times. September 2, 1919. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved September 28, 2020.

- ^ "'World' Presses Damaged by Fire: Blaze in Pulitzer Building Causes General Exodus". Hartford Courant. January 5, 1924. p. 1. Retrieved September 25, 2020 – via ProQuest.

- ^ "The World Printed with the Telegram; Employes End Fight; the World's News Rooms Now Idle". The New York Times. February 28, 1931. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved September 28, 2020.

- ^ "Paper Leases Space in World Building; Journal of Commerce Rents Four Floors for New Home – to Move in a Few Weeks". The New York Times. February 3, 1933. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved September 25, 2020.

- ^ "'Journal of Commerce' To Move to Park Row: Leaving Post office Site for Pulitzer Building Quarters". New York Herald Tribune. February 3, 1933. p. 3. Retrieved September 25, 2020 – via ProQuest.

- ^ "Strong's 'Beekman 3407' Was the Most Famous Phone No. in Baseball". Brooklyn Daily Eagle. January 13, 1935. p. 37. Retrieved September 25, 2020 – via newspapers.com

.

.

- ^ Riley, James A. (1994). The Biographical Encyclopedia of the Negro Baseball Leagues. New York: Carroll & Graf. ISBN 0-7867-0959-6.

- ^ "Park Row Changes at Bridge Studied; Razing of Pulitzer Building and Another Structure to Widen Approach is Weighed. Kracke Developing Plan Program for Brooklyn Span Includes Removing Elevated and Enlarging Streets". The New York Times. July 27, 1936. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved September 24, 2020.

- ^ a b "Pulitzer Building is Bought for Cash; Estate of Publisher Sells Old Home of the N.y. World to Samuel B. Shankman Taken as Investment Structure, Assessed at $2,375,- 000, Will Be Renovated – Was Built in 1892". The New York Times. December 4, 1941. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved September 24, 2020.

- ^ "Real Estate News in the City and Suburbs: S. B. Shanlman Is Purchaser of Pulitzer Tower Investor Takes Large Park Row Building From Estate; Other Transfers Downtown Tower Sold". New York Herald Tribune. December 4, 1941. p. 38. Retrieved September 25, 2020 – via ProQuest.

- ^ "Pulitzer Building Sold". Wall Street Journal. December 5, 1941. p. 13. ISSN 0099-9660. Retrieved September 27, 2020 – via ProQuest.

- ^ "Pulitzer Building Assessment Is Reduced to $2,105,000". New York Herald Tribune. December 31, 1941. p. 27. Retrieved September 25, 2020 – via ProQuest.

- ^ "Old Pulitzer Building's Face Will Get a Bath". New York Herald Tribune. April 5, 1942. p. C2. Retrieved September 25, 2020 – via ProQuest.

- ^ "Biggest Draft Board Moves Its Quarters; Bowery Derelicts No Longer Will Have to Climb Stairs". The New York Times. February 20, 1943. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved September 28, 2020.

- ^ "Socony-Vacuum Leases Space for Training Center: Takes 6,000 Square Feet in Old World Building to Expand Aid to Workers". New York Herald Tribune. January 15, 1946. p. 31A. Retrieved September 25, 2020 – via ProQuest.

- ^ "Ruling Reserved on Zoning Change; Little Favor Shown at Hearing to Protests on Compulsory Parking Facilities". The New York Times. June 8, 1950. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved September 25, 2020.

- ^ "City Planning Unit Maps a New Street; Pulitzer Building Would Be Razed for Proposed Artery Near Brooklyn Bridge Part of the Civic Center". The New York Times. August 10, 1950. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved September 24, 2020.

- ^ "New Plan for Bridge Dooms World Building". New York Daily News. November 23, 1952. p. 415. Retrieved September 28, 2020 – via newspapers.com

.

.

- ^ "World Building May Be Razed For Bridge Plan: Approaches to Brooklyn Bridge, Proposed to City Would Doom Landmark World Building Faces Razing for New Bridge Approaches". New York Herald Tribune. November 23, 1952. p. 31. Retrieved September 25, 2020 – via ProQuest.

- ^ "Plan Marks Doom of World Building; Commission Approves Wagner's $5,266,000 Street Layout for Bridge Approaches". The New York Times. January 8, 1953. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on March 8, 2021. Retrieved September 24, 2020.

- ^ "World Building Reprieve; Board of Estimate Lays Over Plan for Bridge Plaza". The New York Times. January 15, 1953. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved September 24, 2020.

- ^ "Last Newspaper Is Moving Out Of Parle Row: The Journal of Commerce' Leaves 'World' Building for Varick St. Quarters". New York Herald Tribune. February 20, 1953. p. 17. Retrieved September 25, 2020 – via ProQuest.

- ^ "City Set to Buy World Building, Raze It for Plaza". Brooklyn Daily Eagle. June 12, 1953. p. 3. Retrieved September 28, 2020 – via newspapers.com

.

.

- ^ "City Plans Plaza For Other End of Brooklyn Bridge". Brooklyn Daily Eagle. July 24, 1954. p. 2. Retrieved September 28, 2020 – via newspapers.com

.

.

- ^ Bennett, Charles G. (December 15, 1954). "Dust, Noise Drive Mayor From Hall; Wagner and Staff Will Move to World Building Till Work on City Structure Ends". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved September 24, 2020.

- ^ "Mayor to Ignore Demolition Work; Razing of the World Building to Start Monday, but He Won't Vacate Till May 1". The New York Times. March 10, 1955. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved September 25, 2020.

- ^ "Wagner's Office Back in City Hall; His Staff Leaves Pulitzer Building While He Goes on Virginia Week-end". The New York Times. May 14, 1955. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved September 24, 2020.

- ^ a b "Pulitzer Building Stone Not Found". New York Herald Tribune. January 17, 1956. p. 13. Retrieved September 25, 2020 – via ProQuest.

- ^ "Plaza Job Started at Brooklyn Bridge". The New York Times. December 18, 1956. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on October 9, 2020. Retrieved September 28, 2020.

- ^ "Gets Window Today; Columbia to Receive Memento From Old World Building". The New York Times. April 23, 1954. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved September 24, 2020.

- ^ "Pulitzer's Marker Found by Wreckers". The New York Times. February 10, 1956. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved September 28, 2020.

- ^ Berger, Meyer (April 30, 1956). "About New York; Bronx Zoo Discovers What Makes Ponies Jump—All About the 'the' in the Bronx". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved September 28, 2020.

- ^ a b "Box Yields Items of Pulitzer Days; Contents of Cornerstone Box of World Building Recall Earlier Era". The New York Times. February 16, 1956. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved September 24, 2020.

- ^ a b "Pulitzer Building Cornerstone Yields Journalistic Treasure". Press and Sun Bulletin. February 16, 1956. p. 6. Retrieved September 28, 2020 – via newspapers.com

.

.

- ^ Gray, Christopher (June 26, 1988). "Streetscapes: Readers' Questions; a Mailbag of Gargoyles, Dormers, Towers and Stables". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on May 25, 2015. Retrieved September 24, 2020.

Sources

- Landau, Sarah; Condit, Carl W. (1996). Rise of the New York Skyscraper, 1865–1913. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-07739-1. OCLC 32819286.

- "Potter Building" (PDF). New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. September 17, 1996.

- "The New York World Building". Engineering and Building Record. 22: 342–343, 358–360, 374–375. November 1890.

- The World, Its History & Its New Home: The Pulitzer Building. Burr Printing House. 1890.

External links

- 1890 establishments in New York (state)

- 1955 disestablishments in New York (state)

- Buildings and structures demolished in 1955

- Civic Center, Manhattan

- Commercial buildings completed in 1890

- Demolished buildings and structures in Manhattan

- Former skyscrapers

- Former world's tallest buildings

- New York World

- Newspaper headquarters in the United States

- Renaissance Revival architecture in New York City

- Skyscraper office buildings in Manhattan